Chapter 9: This Perilous Coast

The western shores of Vancouver Island are part of the aptly named Graveyard of the Pacific, which has claimed over two thousand ships.1 Sailors have long approached these waters with well-founded fear. Juan de Fuca Strait, an important waterway access to major Pacific Northwest shipping ports, separates Canada from the US. Lost or disabled ships often missed the entrance to Juan de Fuca Strait, were pushed north by currents and storms, and came to grief along these treacherous shores.

Captain E. Cantrillion, a well-known Seattle mariner of the early 1900s, attributed so many wrecks on the southwest coast to a lack of adequate charts, lights and life-saving stations. In the Seattle Post-Intelligencer of December 29, 1905, he described the unique difficulties of accessing Juan de Fuca Strait, stating that ships typically came in from the great circle route on a southeasterly course. This brought them just off Vancouver Island, with barely enough room for a sailing vessel to manoeuvre in a storm. If they ended up just one or two points off, they could easily be driven northward and onto the dangerous shores.

Marine traffic was heavy along the coastline, and shipwrecks were common. The early Victoria newspapers constantly reported tales of errant ships and wreckage sightings, leaving families and friends of missing sailors agonizing for months about the fate of crewmen or passengers who had yet to return home from a voyage at sea. Often reports of wreckage did not include a ship’s name. Any items gathered along rocks and beaches would be sent to the authorities to try and identify the wrecks.

The Colonist often reported ships limping into port with broken booms and sails reduced to shredded canvas. The steamers that regularly travelled up the west coast, transporting passengers and delivering supplies, were also tasked with watching out for the wreckage of missing ships.

Access to the port of Ucluelet was sometimes challenging. Known as “safe harbour,” Ucluelet had many wrecks on her doorstep. Plenty of fishboats were lost over the years, including three halibut schooners that met their demise near Amphitrite Point while trying to reach the safety of Ucluelet Harbour: the Agnes in 1917, the Eagle in 1918, and the Mary in 1921. Although “Carolina Channel…is considered a good one for a stranger to enter…when there is a long swell from seaward heaving in, the entrance often appears to be an unbroken line of surf.”2 Sailing directions for entering Barkley Sound warned of the need for “great vigilance.” This knowledge formed the backdrop for early settlers, and still holds true today.

Some ships floundered farther afield, with their wreckage ending up at Ucluelet. Many wrecks happened in the vicinity of Ucluelet. The Cleveland, one of the first steamships to ply West Coast waters, was fitted with sails to supplement her steam power. In 1897, wild weather off Puget Sound drove her north and onto the west side of the Shelter Islands. Captain and crew launched four lifeboats. One found safety at Spring Cove in Ucluelet Inlet. Two other lifeboats and crews survived after drifting north, past Tofino. The second mate’s lifeboat and its nine occupants were never found.

Sometimes the disappearance of a ship along the Graveyard of the Pacific left an unsolved mystery in its wake. Such was the case of the ill-fated Lamorna. In early March 1904, she left Tacoma, Washington, bound for New Zealand with a load of wheat and barley; in mid-March, rumours circulated that she had come to grief when great gales raged off Vancouver Island’s west coast. One ship captain reported seeing the Lamorna steering aimlessly off Cape Flattery, all decks deserted. Another captain contradicted this, saying he’d seen her off the coast of California. However, substantial debris was found outside Ucluelet Harbour, including a lifebelt labelled Lamorna. Local First Nations men had sighted a schooner run aground on Starlight Reef. When Ucluelet fishermen working near Starlight Reef caught ling cod with stomachs lined with wheat, it was seen as confirmation that the Lamorna had succumbed to the Graveyard of the Pacific.

Sometimes mariners caught a lucky break. This happened with the sinking of the Ada Frances in the summer of 1885. The newspaper account, while acknowledging the dangerous coastline near Ucluelet, was written with a lighthearted touch. After waiting out a nasty southeaster, the sloop left Ucluelet Harbour, drifted sideways onto a reef, heeled over and sank before the crew could get on their lifebelts. An observer reported that “as she went out of sight we saw her crew striking in a Capt. Webb style3 for the shore…and one of the party was throwing water around like a Mississippi stern wheeler.”4 The crew, despite being weighed down by boots and oilskins, made it to shore, where “they stood knee deep in periwinkles awaiting the rescuing party that was en route.”5 The next day, the Ada Frances was raised and towed to Victoria, reportedly none the worse for wear.

The Florencia, 1860

On November 8, 1860, the Florencia, a Peruvian brigantine, left the sawmill at Utsalady, Washington, loaded with lumber bound for Callao. “She was nearly new, and was considered a staunch vessel.”6 Upon exiting Juan de Fuca Strait, the Florencia encountered wild weather and was driven north.

On November 12, the ship was thrown upon her beam ends during a heavy gale, taking on what second mate T.J. Jones later described as “an immense quantity of water, on account of the deck-load.”7 In the ensuing chaos, four men—the captain, ship’s owner, cook and a doctor from Victoria—were swept away by the sea. The loss of life was discovered when, after two and a half hours, the ship righted herself. She limped to temporary safety at Nootka minus her spars and most of her rigging. Captain Barrett-Lennard came upon the scene while circumnavigating Vancouver Island aboard his cutter-yacht, the Templar. By then, the five remaining crew were surviving on distilled salt water. Captain Barrett-Lennard gave them bread and a few other supplies, and noted that by the time he left they had pumped the Florencia dry, assisted by several nuučaan̓uł men. Captain Barrett-Lennard carried on to Victoria, where he suggested that if assistance was sent immediately, the Florencia could easily be towed to Victoria. That is not what transpired.

By mid-December, the gunboat HMS Forward had left Victoria to provide aid. The Forward managed to get the Florencia under tow but had to cut her loose and leave her during a severe gale. The Florencia drifted through darkness and gloom, “at the mercy of the wave and wind,” as crewman John Larkin later described it.8

The next day, they repaired a damaged sail and headed southward. After eight days, they met up with the brigantine Emily W. Seaburn. Captain Trask of that ship gave them “a cask of water, topsail and staysail, three sacks of flour, a box of bread, some tea, two charts and an epitome.”9 He advised they head for San Francisco. The first mate suggested Victoria as a nearer and therefore likelier destination. The Florencia carried on, anchoring in a bay that they determined was on Vancouver Island. When the ship bumped about, they relocated to a nearby cove, again setting anchor. That night, the anchor dragged. As the Florencia drove precariously close to shore, the five remaining crew abandoned ship on a makeshift raft. When they capsized in the surf, several First Nations men rescued them, brought their provisions ashore and escorted the crewmen to nearby Ucluelet.

The cargo of lumber was ultimately salvaged and delivered to Nanaimo by the schooner Alpha.10 John Larkin felt optimistic about the Florencia’s fate, describing her as “lying stern on the beach…Her bottom is sound, and her position is thought to be quite…favorable for being placed afloat once more.”11 But the grounded Florencia, pummelled by the sea, was irreclaimable. The bay where the Florencia came to grief was named Florencia Bay by Captain Richards in 1861, but many locals, myself included, still refer to the area as Wreck Bay.

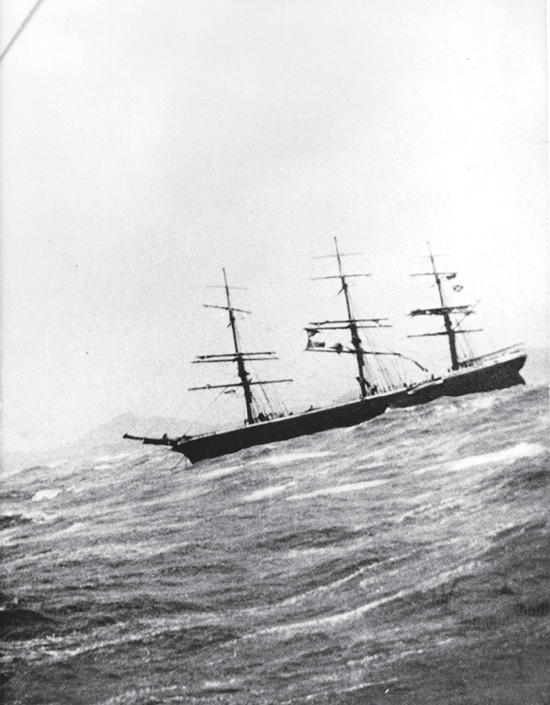

The Pass of Melfort, 1905

Christmas morning, 1905, brought a scene of death and disaster to the outer shore of the Ucluth Peninsula. The wreck of the Pass of Melfort on Jenny Reef, near Amphitrite Point, was both a horrific disaster and a catalyst for life-saving changes along the treacherous coastline of the Graveyard of the Pacific.

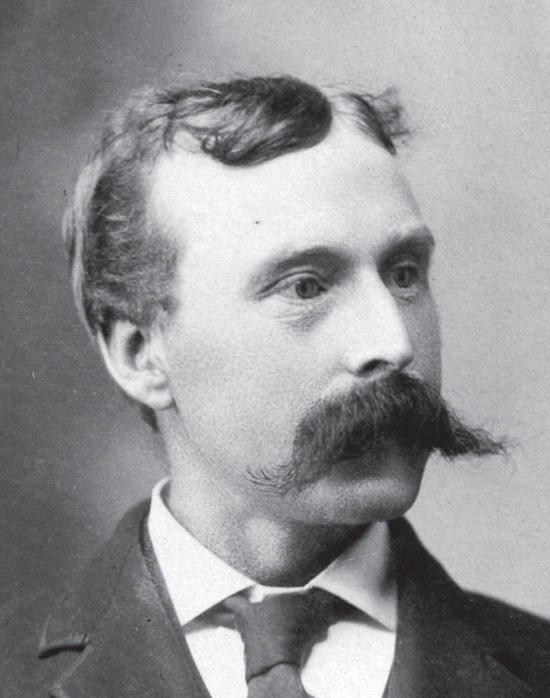

The Pass of Melfort was a four-masted, steel-hulled barque, ninety-one metres long with a gross weight of 2,128 tonnes. Australian-born Captain Harry Scougall had been called out of retirement in Devon, England, to skipper the ill-fated ship. A seasoned mariner, Scougall agreed to assist at short notice, “being, as it was said, a kindly man of friendly disposition.” The previous captain, John Houston, was said to have lost his sanity after going “to the dogs drinking.”12 Houston died in hospital at Salina Cruz, Mexico. By the time Scougall arrived to take command, morale among the crew was low.

As Captain Scougall made last-minute preparations for the voyage from Panama to Washington state, the Pass of Melfort was short-handed. Many of the crew were stricken with malaria. Captain Niven of the steamer Wynerie was tied up near Captain Scougall before the Pass of Melfort left Ancón. He later recalled that Captain Scougall had to send his sickest crew members ashore, and stressed the seriousness of the illness. Niven was quoted in the December 30, 1905, edition of the Victoria Daily Times: “God help the vessel that, with a sick crew, gets into such a storm.”

The Pass of Melfort left Ancón on October 27 under ballast, headed for Port Townsend, Washington, to pick up a load of lumber. She was last sighted off Southern California, by Captain Olson aboard the Brodrick Castle. Captain Scougall signalled they were thirty-eight days out of Panama, bound for Puget Sound. Captain Olson assumed they would see each other there. He did not see the Pass of Melfort again.

Upon reaching the entrance to Juan de Fuca Strait, Captain Olson was caught in a terrible storm, one in which he felt “in great danger,” requiring “the toughest bit of sailing he had ever done.”13 He later theorized that the Pass of Melfort had been caught in the same fierce squalls, torrential downpours, sleet, thunder and lightning, and had been driven up the coast by the strong currents and heavy seas.

In the early hours of Christmas morning, some Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ men heard and saw distress signals across the water from their village. They paddled through a wild storm to Ucluelet village to spread the alarm. Little could be done until dawn. Under the headline “Big Steel Vessel Pounded to Pieces on Jagged Rocks Within Shouting Distance of Shore Near Eucluelet,” one newspaper recounted: “It was not until this morning that with ever-growing horror the little community of Eucluelet bay read on the beach the story of what happened.”14 Most wreckage came into the narrow bay east of Amphitrite, dramatically described by one newspaper as “a small bay, twenty yards wide, with jagged rocks at the mouth on both sides,” where “terrific southwest gales…sweep monstrous seas on to the rocks.”15

August Lyche of Ucluelet telegraphed the news of the disaster to Captain James Gaudin, local marine agent. The dispatch read: “Vessel went ashore last night quarter mile east of Amphitrite point. One body recovered dressed in oil skins and overalls: two more seen washing in the surf, impossible to reach. Several ship’s buckets marked Pass of Melfort, barometer, some cabin wreckage, boat hooks, smashed boats, figurehead of a woman painted white and much wreckage in small rocky bay. No wreckage on either side. Opinion vessel very close to shore. Two spars visible, washing about, evidently anchored…Everything possible being done to recover more bodies.”16

Settlers and First Nations formed patrols to search the rocky coastline. Only two bodies were recovered. Others were seen rolling in the surf or swept up on the jagged rocks. Watchers tried to retrieve them, but had to run back several metres each time a breaker rolled in.

Wreckage strewn along the rocky shoreline included broken furniture, scraps of the ship’s log, a photo of Captain Scougall with some of the crew, clothing, hatches and broken spars and oars. The battered remains of lifeboats, some reduced to splinters, showed fragments of the vessel’s name. More wreckage would later be found at Wreck Bay, four miles northwest of Ucluelet.

Poignantly, the onlookers described the figurehead mentioned by August Lyche as riding “the crest of an incoming wave like a wraith.”17 Reports passed on to the media inspired headlines such as “Wild Seas Sing Dirge over Dead.”18

The two recovered bodies were buried in Ucluelet Cemetery. The Daily Colonist’s headline of December 29, 1905, was “Victims of Wreck Buried at Ucluelet—Without Benefit of Clergy Bodies Washed Ashore Are Laid Away While Villagers Knelt to Pray for Souls of Dead Seamen.” Ucluelet storekeeper M.W. Mackenzie read the burial service. As the impromptu funeral ended, the gale resumed. Mackenzie took George Grant, August Lyche and son to their homes in his boat. He returned to find his store destroyed by fire, likely caused by the gale blowing the stovepipe off. Mackenzie was left with nothing but the clothes on his back.

After the tragic event, the wreck was visible for some time. In 1909, Herbert Hillier was visiting Victoria, where he reported to the Daily Colonist that the submerged wreck of the Pass of Melfort had finally disappeared. He stated that, up to that time, the wreck had been clearly visible in calm water, and inhabitants of Barkley Sound had “made many pilgrimages in boats to witness this monument of the mysterious anger of the sea.”19

In the ensuing weeks, it was widely reported that a woman had gone down with the ship. Many then assumed she had been Captain Scougall’s wife. The story of a woman passenger stemmed from items that washed ashore: “A woman’s gray coat, trimmed with black and red cord, a woman’s No. 3 boot, and one or two scraps of feminine apparel, would seem to prove that the skipper of the lost lumber carrier was accompanied on his last cruise by his wife.”20 However, Captain Scougall’s first wife, Eliza Holland, had died in England in 1901 at the age of forty-five. His second wife, Kate Essery, was safe at home in Plymouth that Christmas, very much pregnant and caring for their seven children. No woman’s body was ever found, so the mystery remains.

There were no survivors, and reports as to how many perished ranged from twenty to thirty-five. Those who estimated the number of victims had no record of crew members who deserted or were dismissed, or of those too ill with malaria to make the trip. Further complicating a true tally, a rumour circulated that the Pass of Melfort had picked up a small party from another stricken ship, the King David, and that they had then died with the Pass of Melfort’s crew. The King David had left Salina Cruz on September 30 and was wrecked on Bajo Reef, west of Friendly Cove, on December 13, 1905.21

As a direct result of the tragic wreck of the Pass of Melfort, demands were made that a lighthouse be established at Amphitrite Point.

The VN&T No.1, 1916

This story of the VN&T No.1 illustrates the power of currents and storms pushing northward from Juan de Fuca. This is a family story I refer to as “The Episode of the Flaming Nightshirt.”

I never met my paternal grandfather. He died twenty-six years before I was born, yet he fascinated me. Like me, he was a redhead, and like me, he was at times impetuous.

On the afternoon of November 14, 1916, my grandfather, Thomas Miller Baird Jr., was at home in Port Renfrew. Having received word from Victoria that his brother Samuel had died two days before, Grandfather Baird was anxious to get to the capital city. Not content to wait for the CPR steamship Tees, scheduled to arrive the following day, he rushed to the wharf in search of a faster means of transport.

Luck (not necessarily the best) was with him. A launch belonging to John Templin’s lumber camp was about to leave for Jordan River, tasked with picking up a donkey engine to bring back to Port Renfrew. They agreed to take Grandfather Baird with them. From Jordan River, he could catch the coach to Victoria.

The group of eight lumber-camp employees, plus Grandfather Baird, set off in the seventeen-metre motor launch called the VN&T No.1. Chris Maylan, foreman of Templin’s lumber camp, was at the wheel. They headed across Juan de Fuca Strait for Neah Bay, intending to buy fuel for the boat before angling back across to Jordan River. They never reached Neah Bay.

Halfway across the strait, the launch broke down in heavy seas. The only one on board who had a hope of fixing the engine was the engineer, Fred Roe. He, however, was soon violently seasick.

As the launch wallowed helplessly in the huge waves, the VN&T No.1 began taking on water. The men soon discovered there was just one bucket on board. As Roe and three others moaned in the throes of seasickness, my grandfather and the remaining functional men formed a bailing bucket brigade, from the bilge to the bow. Bailing went on through that day, that night and the ensuing time at sea.

Meanwhile, as strong currents and huge seas pushed the launch out of the strait to the northwest, news spread that the group had never reached Neah Bay. There were no reported sightings of the VN&T No.1, despite many boats setting out to search. Captain Murray of the Bamfield lifeboat, in what was later described as a “disconcerting message,”22 stated they had withdrawn from the search, citing a need for larger rescue vessels because of severe weather conditions.

Further complicating the situation, an incorrect message was released stating the missing vessel was a tugboat named the Vanity.23

My grandmother, with six children ranging in age from three to thirteen, waited for news at home in Port Renfrew. She was eight months pregnant at the time. On the day after my grandfather’s disappearance, she travelled on the SS Tees to Victoria, arriving at midnight, ready to attend her brother-in-law’s funeral the following day.

I remember my grandma, Annie Baird, with fondness and admiration. She was a fine balance of delicacy and iron-clad will. Those dark November days must have been incredibly stressful for her. The day after Samuel’s funeral, the Daily Colonist reported: “No trace of missing gas boat. May have foundered in Straits.” It went on to state that the mysterious disappearance “seems to point to a tragedy.”24

On the first night of their ordeal, a steamer passed the VN&T No.1 around midnight, just 180 metres to leeward. Grandfather Baird quickly climbed atop the pilot house. A long-time west coast telegraph operator and lineman, he used the only flashlight to flash a code message to the oblivious steamer. As the ship carried on past them, my grandfather leapt down to the deck, pulled his nightshirt from his leather grip, saturated it with oil from the signal lantern, and set it alight. The resultant flare soared three metres high, blazing above the stern of the launch. “The steamer, to their dismay, passed right on, and the men were left to their fate.”25

They had no compass. The nights were dark and cloudy, with no stars visible to help them take their bearings. As Grandfather Baird had impetuously set his nightshirt ablaze, no oil remained to light the signal lantern. Each night brought total darkness. With no further vessel sightings, and having neither food nor water aboard, the men knew their survival depended solely on themselves.

Someone needed to head for shore.

The camp foreman, Chris Maylan, and Martin S. McDougall “gallantly offered to risk their lives for the sake of the others.”26 They set off through the rough seas, using broken oars and a piece of paddle, in the only available vessel, a flimsy four-metre dugout canoe. At this point, they were roughly sixty-five kilometres from shore.27

The two men left the VN&T No.1 at 7 on Thursday morning, rowing almost unceasingly into the early hours of Friday morning. Amazingly, Lennard Island Lighthouse appeared in the distance. Upon finally reaching Lennard Island, they collapsed, soaking and exhausted, on the ground. That they made it to the island seems miraculous. The Victoria Colonist later recounted: “That they reached safety was an act of providence.”28

Maylan and McDougall quickly recovered enough to share their story with the lightkeeper, who relayed the news. The Ucluelet lifeboat crew prepared to head out in their powered lifeboat to retrieve the two men from Lennard Island Lighthouse and then search with them for the missing launch.

Meanwhile, Grandfather Baird and the others had given Maylan and McDougall up for lost and were fast losing hope for themselves. To keep from drifting farther out to sea, they tore up pieces of the deck, tying them together with a rope to tow behind the launch as a makeshift sea anchor. They also fashioned a crude sail with some blankets and a piece of canvas. The launch continued to drift northwest. Then the wind changed, blowing them northeast to within six and a half kilometres of Lennard Island. They had no knowledge of their exact position.

I can only imagine their profound relief when the lifeboat, with Maylan and McDougall aboard, found them in the vicinity of the aptly named Storm Island.29 They were then towed to Riley’s Cove, Flores Island, where both boats anchored for the night. The following day, the lifeboat towed them to Clayoquot, the settlement on Stubbs Island near Tofino. From there, Chris Maylan and four of the others travelled aboard the lifeboat to Ucluelet. They then chartered a boat to Port Alberni, went by motor car to Parksville Junction, and caught the E&N train to Victoria. There, they expressed the highest praise for Ucluelet’s lifeboat crew.

After a brief sojourn in the city, the five men returned to Port Renfrew aboard the SS Tees.

Grandfather Baird and several others remained with the VN&T No.1 at Clayoquot, waiting for a boat to tow them back to Port Renfrew. He had missed his brother’s funeral. Happily, the family had no need to plan his!

My grandfather and the six others rescued on the launch believed that Chris Maylan and Martin McDougall deserved recognition from the Royal Humane Society for their bravery in finding help. Maylan and McDougall disclaimed any credit, maintaining they had done nothing out of the ordinary.

Grandma Baird no doubt begged to differ.

The Nika and the Tuscan Prince, 1923

On February 14, 1923, the Nika, a small US steamer, lost her rudder off Cape Flattery. Shortly after, she caught fire and was soon a mass of flames. The US Coast Guard cutter Snohomish did some fancy manoeuvring in heavy seas and retrieved all thirty-four crew members of the Nika by rigging up a breeches buoy between the two vessels.30 The relieved crew were then delivered to Port Angeles.

The burning vessel, described in the Victoria Daily Times of February 15, 1923, as “a floating menace to shipping,” drifted north. During that same furious gale, the 4,785-tonne British freighter Tuscan Prince struck rugged Austin Island and sent a desperate wireless message reading, “Ship breaking up, we are going to drown.”31 The captain and crew had no clue they were way off course, and relayed their location as somewhere between San Francisco and Seattle. Luckily, a Japanese Canadian fisherman saw the grounded ship as he passed across Barkley Sound, and alerted authorities when he reached Ucluelet. The Bamfield and Tofino lifeboats headed for the scene.

The forty-three crew members of the Tuscan Prince had all made it to shore in the dark and snowy night. Shivering on the rocks, they were excited to see what appeared to be flares from a rescue boat. They were soon disillusioned. It was a ship on fire. It was later deduced that the burning vessel travelled ninety kilometres in twenty-two hours, drifting at an average speed of two and a half knots per hour.32 The sighting of the flaming Nika proved to be serendipitous, for it established the unusual set and drift of the current. This knowledge led to the captain and crew of the Tuscan Prince being found not responsible for the loss of their vessel, owing to the extremely challenging sea conditions at the time.

The lifeboats rescued the men from the island, and they were taken to Bamfield. When the weather calmed, the rocky islet swarmed with souvenir hunters who stripped the wreck of everything portable, including bathtubs.

As the derelict hull of the Nika continued to drift, blowing it up was discussed, but it finally sank just off Ucluelet, at the east side of the harbour entrance.

The Tatjana, 1924

One year later, the 5,300-tonne freighter Tatjana crashed onto the reefs just 360 metres from where the Tuscan Prince had come to grief. En route from Muroran, Japan, to Vancouver for a load of lumber, she had lost her bearings in the fog and could not determine her position. The second mate was also acting as radio operator, and doing so with limited experience. Not knowing Morse code, he sent out a distress call in his native Norwegian, leaving the recipient radio operators, both afloat and ashore, completely baffled and “unable to read the message, let alone decipher it.”33

While others searched in vain for the stricken ship, a radio operator at Pachena Point, southeast of Ucluelet, did some clever calculations and narrowed down her location. The HMCS Armentières towed the Bamfield lifeboat to the suggested area, where they found the Tatjana perched on a reef near Village Island. Several crew members were taken by the lifeboat over to the Armentières, and the rest were left on the wreck as darkness fell. During the night, they rigged a breeches buoy, and all made it to shore. At daybreak, the lifeboat returned to rescue them from their rocky haven.

The Tatjana remained stuck on the reef, sporting a huge hole in her port side, with her engine room and holds flooded and her stern under ten fathoms of water. She was carrying a load of Belgian plate glass. A diver went down to attach the crates of glass to a crane that lifted them out of the water. A boardwalk was constructed, joining the rocky shore to the tilting ship’s deck, and the salvage crew were sheltered in a hastily built structure.34

Despite considerable damage, including a broken-off propellor, the Tatjana was eventually raised, patched and towed by the Pacific Salvage Company to Victoria for repairs. Six hundred workers, divided into three crews, worked around the clock to restore her to her former glory. The Tatjana was then sold to a Norwegian company and renamed the Drammensfjord, and she continued her career as “one of the best freighters ever turned out of a Canadian yard.”35

The Thiepval, 1930

The 324-tonne HMCS Thiepval, a battle-class trawler built in Kingston, Ontario, in 1917, had a varied career. During World War I, she served as a minesweeper in the navy, escorting convoys. In 1918, she was transferred to the Canadian government’s Department of Marine and Fisheries as a patrol ship. In 1923, she was transferred back to the navy to serve on the West Coast. During prohibition, she patrolled for rum-runners along BC’s coast. In 1924, she was the first Canadian warship to visit Japan and the Soviet Union, when she supported a British attempt to fly around the globe.

On February 27, 1930, the Thiepval struck an uncharted pinnacle between Turtle and Turret Islands. The skies were clear and the seas were calm. Ironically, the Thiepval was patrolling Barkley Sound in search of any wrecks or castaways after a recent storm.

Originally at a list of fifteen degrees to port, when the tide went out the Thiepval did a dramatic lurch to sixty-five degrees starboard. At that point, all twenty-two men abandoned ship into lifeboats and rowed to a nearby island, where they ate dry bread, fried pork and a few crab they had managed to catch. The night was bitterly cold, and the men moved their campfires four times as the tide continued to rise.

In the morning, the Thiepval’s sister patrol ship, the HMCS Armentières, arrived to retrieve the shipwrecked crew and await the arrival of a salvage tug from Victoria. As the Thiepval, in a space of thirty-seven seconds, slid down into thirty metres of water, it was clear the salvage tug was no longer needed.

The channel, known at the time of the crash as Broken Group Channel, was renamed Thiepval Channel for obvious reasons.

In 1962, six members of the Ucluelet scuba diving club the Wreck Checkers—Ray Vose, Jim Hill, Malcolm Mead-Miller, Lou Klock and Leslie and George Hillier—raised the cannon from the wreck of the Thiepval, with the help of the Hillier Queen. It took them three dives to unbolt and prepare the cannon to be raised. It is now on display at the Ucluelet harbourfront, below the District Office.

The wreck rests where she sank. She was once a popular dive site, as nearby Turret Island protects the spot from swells, the water is usually quite clear, and the wreck lies next to the reef she hit, meaning there is an abundance of marine life. However, the Thiepval sank loaded with unexploded ammunition, which belatedly caused concern about diver safety. The wreck became off-limits until Canada’s Department of National Defence removed and disposed of the munitions in 2017.

The Barkley Sound, 1946

Sailors frequently found refuge in Ucluelet waters, but there were times when the port did not live up to the name “safe harbour.” That was the case on the evening of February 20, 1946.

Young Hazel Simmell started out the evening filled with anticipation. She was going to a party. The eighteen-year-old had come out to Ucluelet to join her older sister Florence in working at Norm Salisbury’s tea room at Spring Cove. Hazel had originally wanted to help with the war effort by joining the forces, but her parents wouldn’t hear of it. Instead, she was waitressing at the tea room, and so at least got to serve some of the men stationed at the Spring Cove military base.

Hazel was catching a boat ride to the party with Gilbert “Gib” Wesnedge, a young Ucluelet fisherman. Also aboard Gib’s first troller, the Barkley Sound, was sixty-two-year-old Scotsman Jack Lipp, agent at the local Esso station.

Hazel’s excitement about the upcoming party soon turned to trepidation and then fear, as winter winds rapidly increased to gale force. The seas were roiling, and waves grew to four and a half metres. Gib lost control of the troller, and the tumultuous waves pushed the small boat towards the jagged rocks on the east end of Maitland (later Hyphocus) Island, near the mouth of Ucluelet Harbour.

Gib could tell the boat would soon be going down and told his two passengers to abandon ship. He then dove into the raging water. Hazel could swim but remained frozen in place. Jack Lipp couldn’t swim, and knew his time was up. He urged Hazel to get off the boat. For the rest of her life, she would remember his voice saying, “Ye must jump in, lassie!” but she didn’t have the courage.36 Afterwards, Hazel thought a wave had washed her overboard. Then, years later, she decided Jack must have saved her by pushing her off the boat. Either way, she found herself in the dark, fighting her way through churning seas towards the shore. Finally, a wave hurled her onto the jagged, barnacle-encrusted rocks. More waves tried to tear her off, but she clung on with sheer determination. Meanwhile, Gib was being thrashed about, but he stayed afloat by hanging on to a piece of floating wreckage.

A searchlight probed the frightening scene as the Vancouver-based seiner Pacific Belle entered the harbour, seeking shelter from the storm. Their light first illuminated the wrecked Barkley Sound. Then the crew caught sight of a woman clinging to the rocks, and a man in the water, hanging on to floating debris. The crew of the Pacific Belle sprang into action, launching a dory in five-metre waves and rowing through tangled kelp beds to rescue Gib. They headed back to rescue Hazel, who by then was suffering from exposure and barely conscious. Assisted by two Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ men, she was taken to shore and rushed to hospital in Tofino. Gib Wesnedge came through the ordeal relatively unscathed.

Alerted to the disaster, Constable George Redhead went out on the rescue mission, along with brothers George and Bill Hillier on their fishboat Manhattan II, and my uncle Gordon Baird on his troller, the Lilann. They searched throughout the night, temporarily stopping in the morning when the already violent storm worsened. The search then continued for days, and hope for Jack Lipp’s survival was eventually given up. Several First Nations men found the body of the kindly Scotsman two weeks later, on a rocky island outside Ucluelet Harbour. The fury of the storm was illustrated by the fact that the largest pieces of the Barkley Sound to be recovered were no longer than eight inches. Constable Redhead nominated the crew of the Pacific Belle for awards, saying it was “impossible to describe the conditions under which they performed the rescue.”37 Crewmen Emil Anderson, Axel Larsen and Harold Hanson were awarded Royal Canadian Humane Association parchments for bravery in a drowning rescue.

Hazel had suffered serious gashes on her legs. After months of recuperation, she returned home to Ontario. For most of her life, she never mentioned her brush with death, and her family wondered why so much of her artwork depicted rough water and jagged rocks. One day, in her eighties, she told her daughter Debbie the story. Hazel passed away soon after, leaving Debbie to wonder if it was a figment of her mother’s imagination. Then, on a trip to Vancouver Island, Debbie and her husband visited Ucluelet and contacted the Ucluelet and Area Historical Society. Researcher Claudia Cole contacted Gib Wesnedge’s nephew Neil, who confirmed that the story was true.

There were other occasions when using a boat for transportation to a local social gathering ended in tragedy. On October 11, 1947, four workers from Kennedy Lake logging camp at the head of Ucluelet Harbour left a dance at 2 a.m. to return to camp. A strong southeast wind was blowing. Their empty skiff, described by police as “scarcely big enough for two people,” was found adrift in the bay. The body of Michael Halliday, twenty-six, was retrieved from the shore of Kvarno Island three days later. The three other young men were still missing and presumed drowned, and Constable E.C. Domay of Ucluelet promised the search would continue.38 A second body, that of Kenneth Anderson, was found two weeks after the tragic event.

The Glafkos, 1962

As an eleven-year-old girl, I was not about to miss out on the drama of a shipwreck. January 1, 1962, truly was a dark and stormy night. My family was sitting around digesting our New Year’s Day dinner when my father was radioed about a ship in distress. He rushed down to our dock to head out in the Sea Breeze III, the thirteen-metre tug he skippered. My entreaties to go along proved futile. Luckily, the Dawborn family had joined us for dinner. Their daughter Sharon had a driver’s licence, was keen to see the action and drove us down to watch the drama unfold from the shore. Gradually, scores of locals gathered at various viewpoints. So many people stood on Tommy and Mary Kimoto’s porch in Spring Cove that it collapsed under the weight. From where I stood onshore, buffeted by the wind, I peered through the darkness, able to see only bobbing lights, and wondering how Dad was faring in the wild storm. I was not worried about him, as he was a man afraid of nothing. To me, he was always invincible. The scene was chaotic, and it was not until the next day that all the details began to emerge.

The 9,000-tonne, 129-metre Greek freighter Glafkos had been en route under ballast from Japan to Vancouver to pick up a cargo of wheat. Like so many ships before her, she missed the entrance to Juan de Fuca Strait and was now in peril. She ran aground off Amphitrite Point, on Jenny Reef.

One of many newspaper articles later reported that “although Ucluelet is an Indian word meaning peaceful harbor, residents of this tiny village on the isolated west coast of Vancouver Island are accustomed to the mighty Pacific storms which pound on their door.”39

The local paper later reported that first on the scene were George Hillier in his seiner the Hillier Queen, and my father, Ken Baird, in the Sea Breeze III. Heavy seas and gale-force winds stopped them from coming alongside the stricken vessel. Other small boats also came out from Ucluelet in a Dunkirk-like flotilla of support. Ray Vose and Jim Hill ventured out in the six-metre waves in a four-metre skiff and managed to get in so close that the captain of the Glafkos dropped a message down to Ray in a wine bottle. Ray then reportedly relayed messages to the ship’s owner in New York by radio.

The Bamfield lifeboat arrived but was held back by the wind and waves. It must have been a harrowing night for Captain Fatios Petratus and his crew as they waited for morning. They had weathered many storms in their twenty-five-day journey across the Pacific, only to end up in this perilous position. Manoeuvring in rough seas, two large salvage tugs, the Sudbury I and the Island Challenger, successfully pulled the stricken ship from the reef. Then the towline snapped, and huge waves forced her back towards the jagged rocks. Just in time, the anchor went down. An RCAF air-sea rescue helicopter was hovering nearby, and Captain Petratus requested that twenty-two of his crewmen be airlifted to safety. The men were delivered to Ucluelet and given hot meals and rooms at the Ucluelet Lodge.

The ship, its captain and four remaining crew were in dire straits. The holds and engine room were flooded. Without power, the steam winches wouldn’t work, making it impossible to weigh anchor. Local machine-shop owner Pete Hillier and his employee Malcolm Mead-Miller bravely offered assistance. They and their equipment were lowered by helicopter to the wave-swept deck and they severed the anchor chains.

Pete later described the event as “the experience of my life,” adding: “We helped as much as we could, then ate cold eggs and drank beer.”40 With the ship now free, the tugs set off to tow her to Esquimalt. Pete and Malcolm had no choice; they went along for the ride. As the tugs headed for Victoria, the wind dropped and the seas calmed. They made good time on the 160-kilometre journey.

“It was terrible,” one of the Glafkos crew later said, “and then the people came out to us from shore. It made my heart happy. I do not speak English so good, but I know brave men in any language, any country.”41 Another Greek sailor was a former electrician who had been at sea for only eight months. He said, “I would rather be an electrician again.”42

Peter Kostas, who had flown from New York to Victoria to represent the ship’s owner, expressed gratitude to all those involved in the at-sea rescue, and also to those on shore. “When the crew were landed even the ordinary residents of Ucluelet offered them rides in their cars, dry clothes and comfort.”43 Ucluelet public health nurse Myrt Saxton dealt with the only injury resulting from the wreck—a cut forehead requiring four stitches.

Meanwhile, Pete Hillier and Malcolm Mead-Miller, now stranded in Victoria, turned out their pockets to find they had just twenty-nine cents between them. The appreciative authorities provided bus tickets to get them home to Ucluelet.

The tugs had operated with a “no cure no pay” agreement, under a Lloyd’s open-form contract. If they hadn’t rescued the ship, they would not have received a penny. The fee ultimately paid to the owner, Island Tug and Barge, was determined by arbitration in London, England.

When repair estimates to the $500,000 ship skyrocketed to $700,000, the Glafkos was deemed unworthy of repair. A Victoria dismantling firm towed her stripped-down hull to Seattle for breaking up. Thankfully, owing to the courage and resourcefulness of many, the saga of the Glafkos includes no loss of life. The vessel’s skeleton does not rest at the bottom of the sea. But like so many others, the Glafkos was a victim of the Graveyard of the Pacific.

The Vanlene, 1972

It bordered on miraculous that the Vanlene made it across the Pacific from Japan to the coast of BC. And it was not surprising that she ran aground in dense fog on Austin Island, about sixteen kilometres southeast of Ucluelet. She met her nemesis very close to where the Tuscan Prince and the Tatjana were wrecked, some fifty years before her.

On March 14, 1972, the captain sent out a distress signal stating he was somewhere off the coast of Washington state. Like so many others, he had missed the entrance to Juan de Fuca Strait and come to grief in Barkley Sound. Luckily, the tug Neva Straits pinpointed the ship’s correct location and rescued the crew of thirty-eight. Six vessels in all were involved in the rescue operation.

Relieved to be safely off the ship, Lo Chung Hung, the Vanlene’s twenty-nine-year-old captain, related details of their voyage. He had guided the 144-metre, 9,500-tonne freighter across the Pacific using a magnetic compass, after the owners of the Panama-registered vessel refused to repair the ship’s navigational equipment. The owners later disputed his statement, but rescue personnel confirmed that none of the equipment was working when the Vanlene ran aground.

The young captain had thirteen years’ experience at sea, four of them as a master. He attributed 80 percent of the cause of the ship’s going aground to the lack of navigational aid, wearily saying, “But I am still at fault.”44 He added: “It was a bad trip across the ocean, we ran into twenty or thirty gale-force blows and then that dense fog. The fog is your worst enemy because you can’t fight it.”45 Captain Hung, like the rest of his crew, was from China. His expectant wife awaited his return.

The ship’s owners hired Seaspan, a Vancouver-based business that built and repaired ships, to salvage the cargo, which consisted of three hundred new Japanese-built Dodge Colts. However, the federal government saw the urgent need to deal with a potential ecological disaster, so that became Seaspan’s priority. An estimated 226 tonnes of diesel fuel and bunker oil had been spilled, covering kilometres of Barkley Sound shoreline. One hundred and thirty-six tonnes still had to be removed from the ship. The disaster generated much rhetoric in Parliament about who would cover cleanup costs. Getting money from an offshore shipping company wasn’t viable, and Canadian taxpayers were left footing the $169,000 bill. And deciding who would pay for cleanup attempts was no doubt a moot point for the oil-soaked birds now dying on Barkley Sound shorelines.

The federal government was criticized for taking three days to circle the ship with a containment boom. Some of the mop-up equipment proved inadequate for rough West Coast seas. Ultimately, Mother Nature was credited with protecting beaches and intertidal zones when heavy seas, torrential rain and an extreme high tide helped break up the fuel and take it out to sea. In this case, pollution was a reality but considered the lesser of two evils.

Those same heavy seas delayed the salvaging of the cars, but eventually 131 of them were lifted by helicopter, one at a time, and flown over Effingham Island to a barge anchored one and a half kilometres away. Each car took about ten minutes to lift and transport. They were eventually barged to their intended destination of Vancouver. Captain Richard Tolhurst, operations manager for the salvagers, said, “We’re only plucking the bone-dry ones off.”46

The Seaspan office was deluged with phone calls from people hoping to buy salvaged Dodge Colts at bargain prices. They were told they were out of luck; the cars would be held for the consignee, “exactly as if they had been delivered by the Vanlene.”47

With the “bone-dry” cars relocated to Vancouver, there were still 169 cars that had been damaged in the grounding or immersed in salt water, and were left aboard the ship. Each car had its key in the ignition and contained at least a half-tank of gas, causing Bamfield resident Bill McDermid and several friends to briefly consider an innovative scheme. They would “cut open the hull, peel it back like a sardine can and use the makeshift ramp to drive forty of the remaining Colts onto a barge.”48

Once Seaspan had finished their retrieval mission, salvage continued, but on a smaller scale. Many west coast residents visited the wreck, finding useful items or fanciful treasures to take home. RCMP members gave contradictory comments on the acceptability of scavenging. When another RCMP officer requested that people declare the items they removed from the wreck, many complied.

McDermid and his pals didn’t follow through on their dream of driving cars off the wreck. However, some people took engines and car parts from the remaining Colts, despite the corrosive nature of salt water. Clifford Charles of the Bamfield lifeboat station described how people salvaged car parts: “They set up block and tackle and pulled up the motors. They’re nice motors. I’d like one for myself, for my boat.”49

“Wreck-onnoitering”

I explored the wreck of the Vanlene several times that summer while home from university. By then, she had shifted considerably from the power of the waves.

Dad and I went over from Ucluelet in our four-metre boat and tied alongside. We had to leap quickly onto the slanted deck before the next big wave washed up. Wandering through the ruined vessel was an eerie experience. On my first visit, the sound of banging and clunking kept me on edge, nervous that the ship would tip over and pitch me into the sea. But it was thrilling and fun, and when we left, I was eager to return. I coined the tongue-in-cheek phrase “wreck-onnoitering” to describe my adventures on the Vanlene.

Dad was building an eleven-metre pleasure craft at the time, and salvaged some useful items for his new boat, including several teak drawers for marine charts. I brought home a little Chinese-English dictionary I found in one of the deserted cabins. It remains my treasured keepsake for now, until the day comes that Ucluelet has a museum to display it in.

After the ship was wrecked, no one took responsibility. She was said to be for sale on an “as-is where-is” basis for scrap.50 When there were no immediate takers, it was suggested the government pay to have the wreck blown up. Then, on May 25, 1972, Continental Airways Ltd. of Vancouver purchased the wreck. Their plan was to use inflatable pontoons to refloat the Vanlene, then tow her to Victoria for repair or salvage bids.

That never happened. By August, Continental Airways had sold its salvage rights and the Vanlene rested where she sat. Over the next few years, gales and heavy seas continued to wear her down, until eventually the Vanlene slid under the sea, another victim of the Graveyard of the Pacific. Her story is a cautionary tale. Dealing with the fuel spill from the Vanlene did not go smoothly. It brought home the frightening thought of just how much worse it could have been were she a tanker.