Chapter 10: Amphitrite Point Lighthouse

A distinctive and unique structure, Amphitrite Point Lighthouse sits, as firmly attached as any barnacle to a rock, in her strategic position at the south end of the Ucluth Peninsula. She has been likened variously to a Mayan temple, a concrete wedding cake and a stubby bunker. There are those who dare to call her ugly. Once, a letter to the local newspaper actually suggested Amphitrite Point Lighthouse be pulled down and replaced with a “more attractive” lighthouse, like the one at Peggy’s Cove. My answer to that is: “We are not Peggy’s Cove, Nova Scotia, we are Ucluelet, British Columbia.” Amphitrite Point Lighthouse was built with a squat and solid design to withstand the wild weather and unrelenting seas of the Graveyard of the Pacific. The lighthouse has stood proudly for well over a hundred years and is an icon of our West Coast history. Now easily accessible by road and a short walk, Amphitrite is the crowning glory of the Lighthouse Loop section of Ucluelet’s renowned Wild Pacific Trail.

The tragic wreck of the Pass of Melfort in 1905 instigated the building of Amphitrite Lighthouse. The point it sits on was called Punta Terron by Spanish explorers (punta translates as “point or headland,” terron as “clod or thick lump, especially of earth”). In 1859, Captain George Richards named the point after the frigate HMS Amphitrite, a ship named after the Greek goddess of the sea.

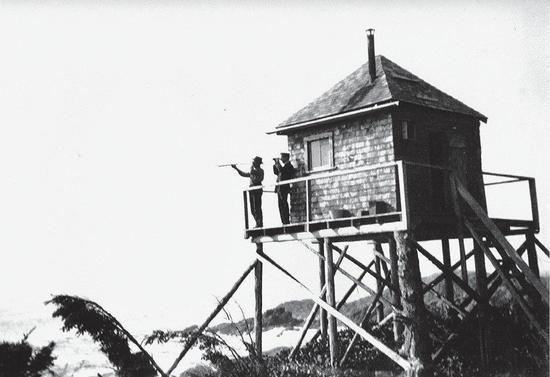

The first “lighthouse” structure, constructed in late January 1906, was a flimsy wooden lookout atop a high rock, adjacent to a gorge. It housed a thirty-one-day, three-wick Wigham oil lamp that gave off light said to be visible for fifteen kilometres.1

Early lightkeepers referred to themselves as “wickies” because their lives revolved around the wick, to “keep a good light.” Renowned horticulturist George Fraser is said to be Ucluelet’s first “wickie,” from 1906 to 1907. The Daily Colonist described the light as “unmanned,” but somebody needed to keep that light shining. Fraser faithfully tended it, hiking return trips every forty-eight hours along the rough trail between his Ucluelet cabin and the wooden lookout at Amphitrite Point. He did this in all kinds of foul weather. Fraser lasted one year before handing the task over to another Ucluelet bachelor. George Grant, like George Fraser, was a Scotsman. Grant played the bagpipes, although whether he did so from the rocky crags of Amphitrite is not known. Grant maintained the lookout light for an impressive seven years.

The Victoria Times was optimistic about the lookout: “The new lamp…should prove of incalculable value to a vessel drifting in close to the island shore on such a night as the one in which the Pass of Melfort went to her doom.”2

The precarious structure provided warning to mariners for a surprising eight years, before being taken by a tidal wave on January 2, 1914. Local Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ citizens reported that “one great sea…swirling in” washed the structure out to sea. “The last they saw of the light…was far out from shore, bobbing up and down on the waters still burning.”3 When the CGSEstevan transported material for building a new lifeboat station at Spring Cove, her crew installed a temporary acetylene light to replace the destroyed light station.

A more substantial structure was desperately needed. In April 1914, six sea captains signed a petition outlining the urgency of the situation. The Ucluelet Development League sent it off with an accompanying letter to government officials in Victoria.

The lobbying stressed the ongoing danger to mariners and the trials of life in Ucluelet. The construction of a new lighthouse would bring much-needed employment to the area. William Thompson, in his letter to Marine Agent Robertson in the winter of 1914, described a settlement of fifteen families “all on the verge of destitution; some are one & two hundred dollars in debt, some stand clear of store bills but no cash in hand.” Thompson wrote that fifty men had no work, but if they left Ucluelet to search for it elsewhere, they would “jump from the frying pan into the fire.”4

Only a small percentage of locals drew a wage—lifeboat crew, telegraph operator, schoolteacher, doctor, policeman and missionary—and this group felt obliged to provide for all the others. Thompson, then lifeboat coxswain, fished twice a week from the lifeboat and donated his catch to the less fortunate.

Times were so tough that the settlement of Ucluelet formed a relief committee, which sent a letter to Robertson describing fifteen destitute families and reinforcing Thompson’s request for employment through construction of “the tower.”5

Thompson stressed that the work on the hoped-for lighthouse could be shared throughout the community, so all able-bodied men would make a living wage. He also foresaw the wives as likely to “jump at the chance” to cook for the work crews.

By Christmas of 1914, things were looking up, with reports of a proposed new lighthouse at Amphitrite Point. On January 6, 1915, the Daily Colonist described the loading of the Leebro with the first shipment of cement and lumber for the project. The Leebro’s crew were about to face the challenges of delivering said cargo. Winter typically brings huge swells and heavy surf onto the rocks at Amphitrite. Time and again, the crew tried to row their workboat in and unload, only to fail and return to the anchored ship still weighed down with supplies. When they nearly flipped in the surf, an alternate plan was created. They would unload in the calmer waters of Spring Cove, near the lifeboat station, and transport supplies by land. These supplies included cement, sand, aggregate, water, timber, bolts, rebar, nails, framing lumber to build forms, machinery and the steel cupola to crown the structure.6

This brought challenges of a different kind. All of February, the rain fell in typical West Coast fashion. The rough route between Spring Cove and Amphitrite became a sea of mud. The men hauled supplies up an incline, loaded it onto a sled and cajoled or harassed the poor draft horses to haul the two hundred kilograms of cargo through the muck and mire. Wheelbarrows were useless, sinking to their axles in mud. One worker dumped precious gravel on the mud to make it passable, and laid poles for a rough corduroy road.

The work crew was drenched by rain and salty spray driven off the sea by incessant wind. Despite these gruelling conditions, work progressed at an impressive rate. As Donald Graham describes in his book Keepers of the Light: “By 8 February they had drilled and blasted 125 yards of rock off the point off the site, hauled seventy cubic yards of gravel and 420 sacks of cement, and were pouring one mix (six cubic feet) of concrete every three minutes of their fourteen-hour days.”7

A.R. Wilby, resident engineer of the Department of Marine and Fisheries, supervised the workers. In February, he updated interested Vancouver Sun readers, assuring them the new lighthouse was built to withstand “the terrible onslaught of the mountainous waves which dash up over the point.”8

Towards the end of March, the structure was largely complete. Marine Agent Robertson paid the crew their final wages. He and Wilby left, likely happy to be heading home.

The Foghorn and the Light

The foghorn at Amphitrite Point Lighthouse was powered by steam produced by burning coal. Two rock ponds hemmed by concrete captured and stored rainwater, which was pumped from a holding tank and then to a boiler to create the steam. (These ponds can still be seen today.)

The foghorn required a detector that sampled the air. When set for two miles, it would cause a blast when there was fog within that range, creating “a mournful two-part wail like an organ out of tune” every eighteen seconds.9 “It must have been unbearable living with the foghorn,” said Mike Slater, who would be the last lightkeeper at Amphitrite. “It’s bad enough living next door.”10

A solid steel door atop the third floor of the lighthouse opened like a hatch on a ship. People climbed through it to clean and polish the windows’ exteriors, a task done daily, in either the afternoon or evening, when the lamp was lit.11

The light assembly seemed a model of engineering. It included a giant clock spring that required winding every eight hours to keep the lamp deck turning. This task frequently had the lightkeepers hiking to the lighthouse in the middle of the night.

A kerosene lamp sat between large reflective mirrors of highly polished stainless steel, each with a circular opening in its centre. Lamp light shone through and reflected out to sea in two sweeping beams for about twenty kilometres.

The light deck floated on a ring of mercury that minimized friction as it rotated. Once the danger of mercury poisoning was discovered, the assemblies were replaced with rollers.12 There are many tales of lightkeepers and their family members losing their sanity. Whether this was caused by mercury poisoning or harsh living conditions in isolated settings was not always documented—perhaps it was a combination of the two. There are no records of insanity among Amphitrite Point lightkeepers, but there are stories of hardship and stress. Those who do not know better may dream of an idyllic life as a lightkeeper, but it is demanding and requires a special breed.

A Lightkeeper’s Lot in Life

Once the structure was built and Marine Agent Robertson left, William Thompson, coxswain of the lifeboat, took charge. The lifeboat crew ran the lighthouse and horn under his direction until, in July 1918, the Ucluelet lifeboat station was closed.

George Fraser’s brother James was hired to be watchman at the empty lifeboat station. For what turned out to be a paltry salary, he took charge of Amphitrite Point Lighthouse. By March 1919 he was airing his grievances in a letter to Agent Robertson: “If $10 a month was your idea of what was fair and just, you might have let me know at once so that I could have resigned & taken advantage of the work in the neighbourhood & been able to earn a decent living.” He made it clear they must find a replacement for him by month’s end.13

Complaints about inadequate pay for a monumental workload were a recurring theme from lightkeepers in the early to mid-1900s. For his ten dollars a month, James Fraser hiked the one and a half kilometres to Amphitrite from Spring Cove at sunset to light the lamp, returned at midnight to wind the mechanism and trim the wicks, and was back again at sunrise to extinguish the light. He did this in weather more foul than fair. He also chopped wood to keep a fire going, as the structure was damp inside from frequent flooding. His work ethic ensured he cleaned and polished all the brass and copper on-site. It was no doubt a great relief to James when a replacement was hired.

Fred and Clara Routcliffe

The new lightkeeper, Fred Routcliffe, was small of stature but large of personality. He and his wife Clara emigrated to Canada from England. Spry and wiry, Fred had been a bantamweight boxer in his younger years. When Fred took over as lightkeeper in 1919, he and Clara tried to create a home of sorts on the second floor. Along with the wood fireplace, there was a cast-iron, coal-burning stove in one corner of the “residence.” Although this sounds cozy, any level of comfort succumbed to the nature of the lighthouse. Smoke and fumes from the engine room came up the stairwell to the second floor. Then there was the noise from machinery, compounded by the foghorn’s mournful tones reverberating in “that concrete echo chamber.”14 After one prolonged period of fog, Fred tendered his resignation but was persuaded to stay on.

Clara Routcliffe had a bad back, the result of being buried in rubble during the first London Blitz. Declaring she had already endured more than her share of stress, she soon refused to live in the lighthouse. The couple moved to Spring Cove and opened a bakery. Fred, like his predecessor James Fraser, then hiked back and forth between Spring Cove and Amphitrite in all kinds of weather, tending the light. Helen Stuart, who grew up near the lighthouse, later said of Fred: “His step was lively, bouncy and brisk. He always carried a rifle, in case of an unpleasant encounter with wildlife.”15

Fred also spent many hours rowing the harbour, delivering his baked goods to locals and seasonal fishermen.

Fred Routcliffe stayed on as lightkeeper for nine years, clinging to promises of an assistant and a lightkeeper’s residence near the lighthouse. Finally, getting neither, he resigned in April 1928. He and Clara moved into a bungalow in Ucluelet, at the top of Main Street hill on the site of the present St. Aidan’s Church building. Finally having free time, Fred was a fixture in the village, and delighted in keeping up on all the news with long chats on the street.

Chris and Hannah Fletcher

The next lightkeeper and his wife, also originally from England, had a home on pre-empted waterfront outside Ucluelet. When they moved to Amphitrite, a newly built, sturdy wood-frame residence awaited them.

Chris Fletcher was a tough man. He had to be. Like the lightkeepers before him, he hauled supplies from Spring Cove through the bush and over a cedar-pole trail.

The Fletchers had a lovely garden at their pre-emption, and also cultivated the property around the lightkeeper’s house. There, they created exquisite gardens including a vegetable garden, terraced rockeries and a large cranberry bog in the nearby brush. They also constructed a huge pond filled with purple water lilies, bamboo, goldfish and carp. Chris and Hannah also built a greenhouse and raised chickens.

The Boardwalk

The cedar-pole trail going through the bush between Spring Cove and Amphitrite was a common route for the lightkeepers. Then a boardwalk was built between Walton’s Bay (now called Birds Bay) and Amphitrite. Good balance was a plus when walking the boardwalk, especially in the sections perched high above the swampy ground. Light-station supplies were shipped from Victoria Marine Depot, usually twice a year. The supply vessels anchored and sent their shipments on a landing barge, which would off-load the cargo, on a high tide, in Walton’s Bay, at the foot of the boardwalk ramp. A wheeled cart would be filled and winched up the ramp with a hand crank, to a landing deck. The cart was about the size of the baggage carts once used at railway stations. This process continued until all the cargo was on the landing deck.

From there, the lightkeeper, sometimes assisted by the supply vessel’s crew, filled his wheelbarrow and went back and forth between bay and lighthouse, a two-and-a-half-kilometre round trip, transporting loads of supplies until the deed was done. The cargo was stored in a big wooden shed, garbed in the traditional red and white lighthouse paint. Eventually, a plank road made transporting the supplies a somewhat easier task.

World War II brought changes to Amphitrite Point. The federal government installed a radar station atop the bluff behind the lighthouse. And because some members of the forces were housed at Spring Cove, a plank road was built joining the cove and Amphitrite Point. The air force also put in telephone lines to connect their operations base at Amphitrite Point with the seaplane base and with their buildings at Spring Cove.

The plank road, like the boardwalk, was built with cedar. The three-and-a-half-metre planks were nailed in pairs atop huge cedar ties which rested mainly on the forest floor. In some spots, they bridged a creek surrounded by swamp. The planks were spaced a vehicle-tire span apart. Keeping your vehicle on the plank road was a tricky business, especially when it was slick with rain or frost.

When the war ended, the radar installation was removed. The plank road connecting Spring Cove with Amphitrite Point remained.

Radar Beacon Installation

After World War II, the telecommunications division of the Department of Transport installed radio beacons in existing lighthouse stations to increase safety for marine traffic along the West Coast. At Amphitrite Point, the installation was built on the site of the former radar installation. It was a large project. In the spring of 1949, workers built a house and office for an operator and his family, and an engine room for two generators.

Delivering the required materials was a major production. A green Dodge truck off-loaded at Spring Cove was used to transport all the shipped materials along the plank road. The little truck carried building materials and household supplies for the new building, plus outside supplies necessary for the radio beacon installation. A government high rigger named Bill Fleming assembled the two fifteen-metre-tall radio beacon masts.

Once everything was delivered, the Dodge truck was left for the use of the new employee and family. Barclay Stuart, wife Thelma and young daughter Helen moved into the residence in June 1949. Stuart, the officer in charge, was ideal for the job. He was a specialist trained in running radio beacons, as well as a telegraphist well versed in Morse code and radio telephones.

The radio beacons transmitted a Morse code signal—the letter A for Amphitrite ·–·–·– pause ·–·–·– pause ·–·–·– pause, followed by seconds of silence, then repeated again for nine minutes, every half-hour, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.16

Helen Watts (née Stuart) later said the house was wired for electricity, with outlets in the walls and bulb sockets in the ceilings… “Only we weren’t rationed any fuel to run our home on electricity. (Except for Saturday Night Hockey on the radio!)”17

The Stuarts’ arrival brought neighbours for the Fletchers. Helen later described Chris Fletcher as a rugged man with “bushy graying red eyebrows and a Father Christmas Face. He was beginning to stoop and move more slowly due to age, arthritis and the very hard physical labour which he endured as keeper. Hannah was taller, purposefully upright and strongly calm.”18 Thelma Stuart recalled that Hannah had a fear of fire, so always kept the house on the cool side.

Barclay Stuart, like Chris Fletcher, had a strong work ethic. Barclay saw the massive workload Chris was carrying and wanted to help. After twenty-one years of managing on his own, it took time for Chris to share the load. Bit by bit, he allowed Barclay to help with the running of the lighthouse. The two families developed a close friendship, maintaining it after Chris retired in 1951.

In June 1950, the arrival of the CGSEstevan heralded a new era for Amphitrite Point Lighthouse, with the delivery of two gasoline generators to run the foghorn. This put an end to the coal-burning steam-production system. As Helen Watts said in her March 2015 presentation on the history of Amphitrite Point Lighthouse: “No more hauling coal in a wheelbarrow from the red shed at the end of the boardwalk. Now it was rolling 45-gallon drums full of gasoline up all those cement steps…. What an improvement!”

Supply Days

Supply ships delivered people and supplies to the lighthouses. The captains and crews of these vessels were brave and skilled navigators, battling wild weather and tumultuous seas. They also installed and reinstalled warning buoys, putting themselves in danger so that others could safely navigate the treacherous West Coast waters.

The CGSEstevan, built in 1912, acted largely as a lighthouse supply vessel and buoy tender. When the Estevan served as supply ship for Amphitrite Point during the 1950s, she was fuelled by coal. Helen said their “first sight of her arrival was a dark smudge of black smoke on the horizon,” so they lovingly referred to her as “Smoky Joe.”19 (In 1958, the Estevan was converted from coal to oil fuel.)

The Estevan’s arrival was always welcome. Helen spoke nostalgically of supply days. “We children—the Cove kids, the Lighthouse kids, sometimes Town kids—and always Helen—would wander down to the wharf at Spring Cove.”20 There, they kept out of the way while taking in the exciting activity.

The crew routinely unloaded 350 forty-five-gallon drums of fuel from the supply ship to a landing vessel, which took them to the wharf. There, they were rolled up to the truck and manhandled into the box, which held three drums. The pickup was driven along the plank road to Amphitrite, where each drum was unloaded and wrestled into an upright position. Helen did the math: there were 117 trips to and from Spring Cove just for the gasoline drums. “Then there were drums of kerosene for the lighthouse lamp. And so on.”21

The kids all loved the hustle and bustle of supply days. When the unloading was finally done, with any luck there’d be a kind word from the ship’s captain, usually Monty Montgomery. The crew would load up to fourteen kids in the workboat and take them for a spin “out of the Cove, out around the Estevan where she was anchored in the entrance of Ucluelet Harbour, then back to the wharf. Childhood heaven!”22

The Yodelling Lightkeeper

In a roundabout way, World War II was responsible for the arrival of a new lighthouse employee. When Adolph Heiler was seriously injured in his home country of Germany during the war, Canadian troops transported him to a first-aid station, where he received life-saving transfusions of Canadian blood. After the war, Adolph made his way to Canada, finding a job in the Port Alberni pulp mill. But Adolph longed for a quieter, more low-key place. His dream came true when he visited Ucluelet in the mid-1950s.

Serendipitously, the assistant lightkeeper at Amphitrite Point had just resigned; Adolph was hired on the spot. He was a conscientious employee, and also made good use of the little spare time his position offered. A gifted artist, he painted en plein air and took many photographs to reference for further paintings. Arthur Lismer and Frederick Varley, of Canada’s famous Group of Seven, both visited Adolph to view and discuss his paintings.

Adolph had grown up in the Bavarian Alps. A seasoned yodeller, he sometimes entertained Helen and her friends. Adolph found that the lighthouse’s second floor provided the best acoustics, possibly because the windows there had been filled in with concrete. “He’d send us off down the steel ladder to the main floor,” Helen said, “then would joyfully ring the cement rooms with the beautiful sound.”23

Progress: Pros and Cons

In 1957, a gravel road was built over the trail between Spring Cove and Ucluelet. Next, sections of the plank road from Amphitrite to Spring Cove were bulldozed and replaced with gravel. This gravel road connected with the new one between the cove and Ucluelet. Helen later said, “I must say that with the road, we lost a little bit of the magic.”24 (I felt the same way when the road was put through to Port Alberni in 1959.)

The changes continued at Amphitrite Point. In 1961, a new lightkeeper’s house was built, and electricity arrived in 1962. Before that, there were just a few dim light bulbs in the first and second floors of the lighthouse, stemming from a very weak electrical current created by batteries. The families in the two houses used gas lamps, and a gas iron for ironing clothing. Helen recalled that overly brisk strokes with the iron caused flames to shoot out its sides. October 7, 1962, was the momentous day when the homes and lighthouse at Amphitrite were connected to electricity from Ucluelet. Young Helen Stuart had the honour of switching on the first electric light.

The Stuarts moved to the brighter lights of Vancouver when Barclay retired in 1965. At a farewell party at the Ucluelet Athletic Club Hall, the popular couple were presented with two easy chairs—a fitting gift as they headed into well-deserved retirement.

Windstorms and Wildlife

Jack Thompson worked as assistant lightkeeper at Amphitrite in the 1960s, and was still there when Barclay Stuart retired. Jack’s family often remained in their house at the foot of Fraser Lane, and his wife Norah stayed with him at the lightkeeper’s house on weekends. Jack’s daughter Ann Branscombe recalls surprising her dad on his birthday. She and some friends took kitchen chairs into the unfurnished living room, where the linoleum was rocking like the sea, owing to the wind blowing under it. Ann was quick to clarify that this was before they’d even opened a bottle of wine.

One time, when Ann went to the lightkeeper’s house during her lunch break from the Co-op, she had to drive through deep, brown seafoam covering the road. When she reached the house, the sea was crashing right over the lighthouse.

In those days, a gate blocked road entry to the lighthouse property. Ann got out of the car one cold dark night to unlock the gate and heard what sounded like a baby crying. She quickly twigged that it was a cougar and got back into the car in short order.

The End of an Era

In the 1980s, the Canadian Coast Guard produced a plan to drastically reduce the number of staffed lighthouses on the West Coast. After public outcry, they briefly backed away from the plan in 1987. The next year, however, Amphitrite Point Lighthouse and four others lost their keepers. Amphitrite became automated. Mike Slater was the last lightkeeper of Amphitrite Point. He and his wife, Carol, moved on to his reassignment on Trial Islands near Oak Bay that summer.

“It’s just unfortunate that the only people who are going to lose are the people who depend on the service,” Carol said.25 She and Mike both stated they loved their many years on lighthouses and wondered “what the bureaucrats are thinking thousands of miles away.”26

The unmanning of Amphitrite Point Lighthouse was the end of an era, but the unwavering light continues to guide mariners past dangerous rocks and reefs into Ucluelet’s safe harbour.

A Sight for Sore Eyes

One sweltering day in the summer of 2012, my husband and I had just arrived in Split, Croatia, after a long uncomfortable bus ride from Mostar, Bosnia. The bus was hot and stuffy, and we had both forgotten to fill our water bottles. As we stumbled through the scorching cobbled streets of Split, searching for our hotel, I was exhausted, irritable and fighting back tears. A shopkeeper kindly directed us to our hotel, which we had passed by three times, as it was built into the city’s stone wall.

Upon entering the little family-run hotel, we were welcomed and directed up a short flight of stairs to our room. The girl at the front desk called out: “You can use the computer whenever you want!” I looked up through bleary eyes and saw the computer, and on the screen was a gorgeous photo of Amphitrite Point Lighthouse. I burst into happy tears.

Refreshed after a cold shower and a long nap, we headed back downstairs. I asked the girl how that screen saver ended up on their computer. She told me they were given a choice of “the five most beautiful places in the world” and they chose that one. We proudly explained it was from our hometown. From then on, while we stayed at that lovely little hotel, we were referred to as “the people of the screen saver.”