Chapter 6: Spreading the Gospel

In Canada, colonialism and religion were hand in hand. Explorers considered it their given right to seize land for their home countries. Missionaries focused on imposing Christianity on the inhabitants of the supposedly “discovered” lands. But the zeal for conversion saw the establishment not only of missions, but also of many small community churches for the new residents. While providing a base for devoted congregations, these churches served as community hubs for the non-religious.

The Catholic Mission

Catholicism arrived in Ucluelet by ship, delivered by Bishop Charles Seghers and Father Augustin Joseph Brabant. Their faith was strong and their mission entrenched; they were here to convert the Indigenous people of Vancouver Island’s west coast.

The two missionaries left Victoria on April 12, 1874, heading up the coast aboard the schooner Surprise with Captain Peter Francis in command. In his diary, Father Brabant made an oft-repeated comment about Francis, recording delays in their progress as resulting from the fact that “our Captain was now…badly intoxicated.”1

On April 18, after anchoring overnight at Effingham Island for “a very comfortable night in smooth water,” they were “up and away at 5 a.m. Rain, heavy sea.”2 They reached Ucluliat (Ucluelet) at about 9 a.m., and the young Chief Wish Koutl immediately came for them in his canoe. As they approached the shore, members of the Ucluelet First Nation rushed down to greet them, one firing his gun in the background.

Brabant wrote: “Our arrival caused a great deal of excitement. Our interpreter had a thundering voice, but we were told he did not translate His Lordship’s words with much correctness. Perhaps he thought that shouting would have the necessary effect. I baptized seventy-five children in the afternoon.”3

The next day being Sunday, Mass was held at 5:30 a.m. in the storekeeper’s house, “and then at 8 a.m. off to the rancherie [a term used at the time to refer to a First Nation village or settlement].”4 Some First Nations from Clayoquot joined the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ and nine of their children were baptised. “Here the first effort was made to translate the sign of the Cross into the Indian language.”5

The next morning, Father Brabant and Bishop Seghers continued up the coast aboard the Surprise, visiting First Nations villages along the way, with mixed responses. At Kyuquot, they oversaw the “planting” of a large mission cross crafted at their request by Captain Francis and first mate Peterson, a “Swedish Lutheran.” Before the cross was set up, Bishop Seghers made a speech “condemning all Indian superstitions in general.”6 Fifty young men in three canoes transported the cross to a small island. Brabant wrote: “It was beautiful to see the Indians struggle to carry the heavy burden.”7 Ironic words indeed, considering the heavy burden about to be inflicted on the First Nations people by the zealous missionaries determined to eradicate Indigenous culture and beliefs.

At Kyuquot, they left the ship to travel by canoe through churning seas to area villages. (Father Brabant often referred to canoe trips in which “the sea ran mountains high,” with wave troughs so deep he felt he was in “the abyss of the ocean.”)8

Interpreting their reception at Hesquiaht as positive, the bishop declared it the perfect place to start a mission, adding that area Chiefs offered him “a site of his choice.”9 Promising to return, the clerics boarded the Surprise and sailed to Victoria on a favourable westerly wind.

Not all trips up and down the coast went smoothly. On one journey, when the sea was too rough to launch a canoe, they walked from the head of Tofino Inlet to Ucluelet. En route, a black bear visited their tent, they got lost in the woods in torrential rain and they scorched a shoe and their clothes on a bonfire. The bishop fainted from hunger and exhaustion but was revived with raw mussels, salal berries and boiled doughnuts cooked over a fire. After they finally reached Ucluelet, they needed two weeks to recover, but their passion to convert the West Coast First Nations people persisted.

On May 6, 1875, Father Brabant returned to Hesquiaht to build the mission. He said his first Mass in the newly constructed church on July 5. Brabant complained that the First Nations Elders undermined him, “using all means in their power to keep their influence over the people,” and “making speech after speech to the young men to stick to the old practices.”10 When one “great favourite and very much liked” powerful orator died, Brabant described the death as “almost a blessing for our work.”11

Brabant remained determined to achieve his goal, writing, “I am having a great time here,” and enthusing about his “great parish.”12 He considered himself “in charge of all the Indians from Pachena to Cape Cook,” and wrote in his typical condescending manner that “their superstitions are so numerous and so absurd that they are almost incredible.”13

At times discouraged, Brabant wrote: “They laugh at the doctrine which I teach. I gain nothing by making the sign of the cross. I am neither a white man nor an Indian. I am the Chigha, the devil.”14 In a letter to his brother in Belgium, Brabant described facing hostility “with no other weapons than our breviary, our beads, and our crucifix.”15

The priest documented many practices and traditions of the Nuu-chah-nulth people. But he did so with a judgmental and bigoted attitude. Oblivious to the importance of their traditional songs and music, he returned from a trip home to Belgium in 1900 with “a full set of brass instruments for the Hesquiaht band.”16

Despite the missionaries’ attempts to eradicate the use of Indigenous languages, Brabant created “an extensive dictionary and grammar…composed of the Nootkan Language.”17

Christie School

The Catholic and Presbyterian missionaries on the West Coast constantly competed to “save souls.” Father Brabant complained that one young Presbyterian minister “will do nothing himself” but would take credit for work done by Brabant and fellow missionaries.18 Brabant was eager to set up an industrial school for the Indigenous children, to prevent the Protestant missionaries from exerting what he saw as a negative influence. (Industrial schools were residential schools where the pupils worked at tasks such as gardening, livestock care, carpentry, laundry and sewing.) Bishop Seghers supported the school idea but was murdered in Alaska in 1887. His replacement, Bishop Alexander Christie, urged Father Brabant to set up a boarding school quickly, and Brabant chose a site on Meares Island, near Tofino, on the shore of Deception Channel. The building of Christie Indian Residential School was completed in 1899. The first staff were from the Benedictine Order in Oregon. In 1938, the Oblates took over, followed in 1969 by the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

Over the years, students made several unsuccessful attempts to burn Christie School down. In 1971, the school closed and students moved to a new residence at Tofino. When that facility closed in 1983, it was the last functioning residential school in BC. In 1974, after lobbying by several former pupils with a vision for positive change, the structure on Meares Island became the Ka Ka Wis Family Development Centre. It served as an addiction treatment centre for over thirty years, before the program was relocated to Port Alberni.

Holy Family Church

Before 1952, priests travelling from Christie School to Ucluelet held services in the pool hall, parishioners’ homes or other available halls. Then Father Michael Kearney of Christie School spearheaded a drive to build a church. The target date for completion was Christmas Eve, 1952.

Vince Madden, owner of Madden’s General Store, donated two lots on Peninsula Road. The forestry company MacMillan and Bloedel provided some building materials, and everything else arrived by boat. The local Catholic ladies’ group fundraised with teas, bazaars and raffles. Cash donations swelled; when Peter Sullivan loaned $3,000, the goal was reached.

Ucluelet resident Stan Doiron, an experienced carpenter, oversaw the construction done by volunteer members of the parish. Father Kearney motivated everyone towards completion.

Midnight Mass was celebrated in the new Holy Family Church on Christmas Eve, 1952. Bea Brennan said it was memorable in more ways than one. “With no heat in the building, everyone nearly froze.” She added that the “inconvenience was overshadowed by the joy of accomplishment.”19 Also celebrating that first service were parishioners from Tofino and local non-Catholics. Holy Family Church was consecrated in July 1953 by Bishop James M. Hill.

Services warmed up when Jack Day built a brick chimney. He travelled back and forth by boat from his family home in a bay beyond the entrance to Ucluelet Harbour. The site of their home has now been developed but is still referred to by many as Jack Day’s Bay.

Loyal parishioners continue to support Holy Family Church. The ladies group’s annual apple-pie fundraiser is legendary. Over the years, talented musicians, including Margaret Winpenny, Edna Camp, Johnny Coffin and Melissa Webb, have accompanied the parishioners as they raise their voices in song.

Rev. Melvin Swartout

The first Presbyterian mission on the west coast of Vancouver Island opened in Ucluelet in 1890, under Rev. J.A. MacDonald. After four years, he was replaced by Rev. Melvin Swartout, who moved out to Ucluelet from Ontario in February 1894 with his wife Mary and daughters Nina and Viola.

Rev. Swartout’s years at Ucluelet have been described in glowing terms from a colonial perspective. One book states: “at Ucluelet…he wrought nobly and built up a strong cause. A church was erected, a house for the missionary and his family, and a school for the Indian children. His work prospered from year to year.”20

The renowned West Coast painter Emily Carr’s sister Elizabeth volunteered for a time at the mission school, as recounted by Emily in her book Klee Wyck. The mission house was about one and a half kilometres from the village now known as hitac̓u, and the day school halfway between.

The arrival of Rev. Swartout brought an added convenience for residents. He became the first registrar of licences under the Marriage Act for Ucluelet, meaning couples could “enjoy the convenience of…marriage solemnized in their midst without a journey by sloop or trail or steamer to comply with the formalities.”21

Melvin Swartout was said to be proficient in the local First Nations language. In 1899, he created a booklet, purportedly written in the Aht dialect of Barkley Sound, that included an alphabet, suggested pronunciations, and translations of the Ten Commandments, Lord’s Prayer, the Beatitudes and twelve hymns.22

Swartout is also credited with sharing details of a First Nations oral story called “The Legend of Eut-le-ten” in 1897. Alfred Carmichael, an acquaintance of Swartout’s in the 1800s, attested to his linguistic ability: “He spoke the language of the natives fluently, and took great pains to get the story with as much accuracy as possible.”23 Whether Swartout had permission from the Nuu-chah-nulth to share their oral story is undocumented.

Swartout often spoke up in defence of the local First Nations people in times of trouble. For example, when the Cleveland was wrecked nearby, eleven “Eucluelet” and Toquaht men, as well as one white man, McCarthy, were accused of removing articles from the steamer. Swartout supported the men in their claim that they had been permitted to salvage items from a previous wreck, and therefore could not see why this case would be different. Further to the accusations of thievery, Swartout stated in a letter to the editor of the Colonist: “In the harbour, before my house, as I write, there lies at anchor my little sailboat, provisioned and equipped for a voyage. It has been lying thus for several days, detained by contrary winds. Indians are passing and repassing constantly. Many things of value to them are there, with no lock and key to prevent them from helping themselves, but nothing is missing, nor have I the slightest fear that anything will be taken. Could there be such an experience in any civilized city or town in Canada?”24

The little sailboat mentioned in Swartout’s letter later led to his demise. An experienced and confident sailor, he made frequent trips along the coast. On July 11, 1904, Rev. Swartout was sailing back to Ucluelet, having visited Rev. James Motion in Alberni. He dropped a settler off at his property sixteen kilometres out of Ucluelet. The man later described standing “on a rising ground watching the receding sailboat and its lonely occupant until they disappeared round the point north of his place.”25

The wind had come up, churning rough seas, and Rev. Swartout did not make it home to Ucluelet. It was hoped that the “hardy and daring sailor”26 had taken refuge in a sheltered cove, but faith soon faltered. Mrs. Swartout telegraphed Rev. Dr. Campbell in Victoria: “Mr. Swartout in sailboat, missing for 5 days; grave fears for his safety as weather very rough.”27 Fear compounded when a piece of his boat was found washed up on a beach near Toquaht, and another piece near Ucluelet Harbour. Closure came almost three months later. The Colonist reported: “The body of the Rev. Mr. Swartout was washed up on Long Beach yesterday. The face was badly disfigured, but the clothes were intact with the exception of one shoe and one sock. His watch had stopped at 5:10…the remains are at Dr. McLeans’, awaiting burial.”28 Rev. Melvin Swartout was interred near Hitacu.

After Mary Swartout left the Ucluelet mission, laymen served the Presbyterians until Joseph Samuel was appointed in 1910, followed by Thomas Shewish in 1912. Then Ucluelet became part of the West Coast Marine Mission, which encompassed all of Barkley Sound.

Anglican-United Ministry

Formed before 1910, the West Coast Mission covered an area from Port Renfrew to Kyuquot. The Anglican diocese of BC provided a clergyman to serve the west coast of Vancouver Island. In 1913, St. Columba was built in Tofino, after the site was deemed the prettiest place on Vancouver Island. A family in Portsea, England, donated the money in memory of their son, who had drowned in the English Channel. Two curates from Portsea ministered to Tofino and Ucluelet over a seven-year period, living in a shack built for them in Tofino. Services in Ucluelet were held in the original schoolhouse.

Padre Leighton

The Reverend John Wright Leighton was a colourful character and popular West Coast cleric. Born in Bristol, England, in 1887, he served as an army chaplain in World War I. After the war, he married his childhood sweetheart, Florence, but lost her to the Great Influenza epidemic just four weeks after they wed.

Padre Leighton, as he was affectionately called, came to Canada in 1926, and arrived to serve Ucluelet, Tofino and surrounding areas in 1930. He covered the west coast territory from Pachena Point Lighthouse up to Kyuquot. Padre Leighton often travelled on the Princess Maquinna, and when boarding or disembarking was dressed for the weather in his oilskins, gumboots and rain hat, with his pipe sticking out the side of his mouth. He was a true “wet coast” vicar.

Long-time Tofino resident Ken Gibson shared a Padre Leighton story with me. In the late 1950s, Ken, a member of the Tofino Volunteer Fire Department, was attending a fire well after midnight. Something large and pinkish-white drifted into his peripheral vision. “I thought it was a ghost,” he told me. Turning, he saw Padre Leighton wearing a long, fluffy dressing gown.

“Do you think the crew might like to come to my place for a ‘wee nip’ after the fire is out?” asked the Padre.

“I don’t think so, Padre,” replied Ken. “It’s the middle of the night. They’re pretty tired. I think they’ll just want to go home to bed.”

Padre Leighton, like many a west coaster, enjoyed his liquid refreshments. One morning, after indulging in “too much Christmas cheer,” he left the church mid-service to be “quietly sick in the churchyard, and returned with a smiling apology.”29 He also had a fondness for sake made by local Japanese Canadians, “consuming impressive amounts without ill effect.”30

Padre Leighton left the west coast to serve for twenty years as chaplain with the Mission to Seafarers in Vancouver. There, he and his shaggy dog Kim became well-known figures, seen “aboard nearly every ship that visited the port.”31

Padre Leighton attempted retirement in Victoria in 1955 but decided after two months that “life was too short to waste in this manner.”32 Returning to serve on the west coast of Vancouver Island, he was pleased to have a car at his disposal, no longer having to travel between Tofino and Ucluelet by canoe, by gas boat or on foot. In 1962, Padre Leighton, suffering ill health, began his well-earned retirement years.

St. Aidan-on-the-Hill

St. Aidan-on-the-Hill stands proudly at the top of Main Street. Now renovated and repurposed, this iconic building was once the centre of the Anglican–United ministry of Ucluelet.

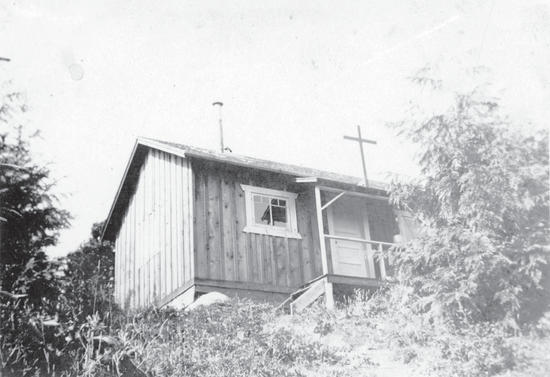

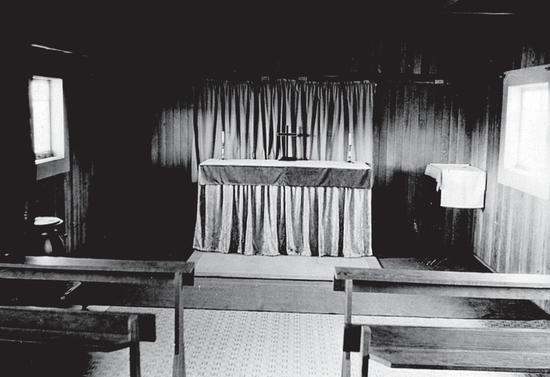

On October 5, 1929, a plot of land and a building were purchased for $400, and Ucluelet became home to the smallest church on Vancouver Island—some said the smallest in BC. December 29, 1929, saw the first service, Morning Prayer, in the little church. The first wedding was that of Josephine Binns and William Littleton, on September 26, 1931.

On January 1, 1949, Rev. A.H. Holmes arrived on the west coast of the island with wife Frances and daughter Elaine. They moved into a tiny house next to the Ucluelet Co-op. (The building was later used by Ralph the Veggie Man and then the Greenhouse Market.) A rectory was built in Tofino with wood salvaged from the dismantled RCAF hospital at Long Beach. Daughter Maureen, who was born after they moved to Tofino, recalled pots and pans spread across the floor to catch rain leaking through the roof.

Rev. Holmes, like the clergy before him, served both communities. He was prone to tardiness, and his parishioners soon took to calling him “the late Reverend Holmes.” His sister Muriel Toombes also tended to be late. When she worked at Madden’s General Store, her boss Margaret Thompson would set off an alarm clock when Muriel arrived at work. All in good fun, of course!

In 1950, to cut travelling expenses, the joint parishes bought a motorcycle for $250, and said there could be no more taxi fares. Rev. Holmes was six foot five—he towered atop the blue motorcycle as he rode back and forth over the rough gravel road between Tofino and Ucluelet. He was also a pilot and flew shoeless so his head wouldn’t brush the inside of plane cockpits; this earned him the moniker “the Barefoot Pilot.”

A New Church for Ucluelet

Rev. Holmes said Ucluelet needed a larger church. The locals agreed, and in 1949 a committee was formed at the annual St. Aidan’s vestry meeting. Like the Roman Catholic Holy Family Church, the new St. Aidan’s would become a reality through community commitment and hard work.

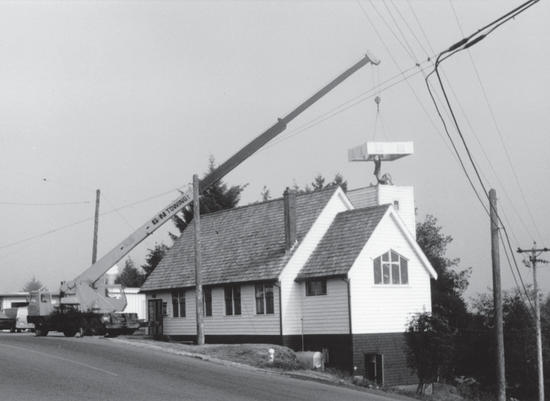

Sutton Lumber and Trading Company donated a former RCAF building. Local volunteers, many of them fishermen who had relocated to Ucluelet from Newfoundland, spent three winters dismantling the twenty-seven-by-twenty-eight-metre building. They saved and straightened every nail for use in the church-to-be.

The tiny church was moved down to the bottom of the lot, close to what is now the site of Blackberry Cove Marketplace. Plans for the new church snowballed, necessitating major fundraising. The Anglican Church Women’s group was revived, with close to thirty members. Rev. Holmes, discovering that weekly picture shows were about to be cancelled, seized the opportunity to raise some cash. He borrowed money for a projector and ordered in films. Ten different movies were shown in December 1952, including The Painted Hills starring Lassie, and Joan of Arc with Ingrid Bergman (in Technicolor!). The movies played to packed houses, with frequent intermissions when the film broke. Popcorn sales boosted the profits through a canny sales pitch: one bag of popcorn was ten cents, but twenty-five cents would buy you two!

Finally, after seven hectic months of work, it was time to celebrate. The official opening of St. Aidan-on-the-Hill took place on December 7, 1952. A special guest preaching that day was Padre John Leighton, who had earlier served as the west coast clergyman, and would return to the position in 1955. The rafters rang with joyful music, not only from adult and youth choirs, but also from Rev. Holmes’s daughter Elaine, who, along with friend Diane, had been convinced to sing “ Fairest Lord Jesus.” When Diane quit singing, the duet became a solo. Elaine’s younger sister Maureen later related that by the time eight-year-old Elaine concluded, there “wasn’t a dry eye in the crowd.”

The tiny church down the hill was the local library for many years. It also served as a bank. In 1960, the Synod gave permission to sell the building, but there were no takers. A branch of the Ucluelet Recreation Commission called Teen Town was given the use of the little church as a coffee house in 1966. We local teens gave it the moniker “Snoopy’s Place,” then changed it to “Society’s Child” and painted the interior in bright colours. It was a popular spot for teens to hang out on Friday nights, listening to music and drinking coffee. Later, it was taken over by Norma Baillie as an arts and crafts shop. Sadly, in 1969 the original tiny church was torn down and the lumber sold.

From 1959 to 1968, United and Anglican ministers alternated officiating at St. Aidan’s every four years, serving a combined Anglican and United congregation. During these last years of shared ministry, a tragedy at sea occurred, reminding many of the sad demise of Rev. Melvin Swartout so many years before.

A Death at Sea

Saturday, March 29, 1965, was a sunny day with winds picking up to thirty-two kilometres per hour. Rev. Stuart Schoberg, the thirty-four-year-old incumbent United Church minister for Vancouver Island’s west coast, left Ucluelet in his three-and-a-half-metre outboard at 11 a.m. to visit parishioners in Tofino. He didn’t arrive.

Three days later, searchers found Rev. Schoberg’s water-filled boat three kilometres off Amphitrite Point. It was assumed that at some point on his journey the boat was swamped and he was washed overboard. Once his boat was picked up, the air search was cancelled, but small boats continued searching for a full week.

Long-time Ucluelet resident Bud Tugwell, a St. Aidan’s parishioner, had strongly advised Rev. Schoberg against making the trip, but the young minister chose to go.

On April 6, St. Aidan’s Church was filled to overflowing for his memorial service. Just two weeks before, Rev. Schoberg’s voice had echoed through the church. Now his friends and parishioners spoke in his honour. A congregation member described him as “a most outstanding, dedicated and highly esteemed clergyman.”33

Rev. Schoberg, his wife and two young sons were to have been in Ucluelet for just three more months, before moving to England, where he was to take up a fellowship. On May 10, a ruling was issued that he was presumed drowned. Mrs. Schoberg and sons moved to Vancouver in June. In July of that year, Rev. Schoberg’s body washed up on the beach at Wreck Bay.

The United Church Withdraws

The shared ministry officially ended in June 1968, when the United Church withdrew from the west coast area. During the period of shared ministry, Anglican diocese funds helped pay for a new rectory. Built on Helen Road, it housed many incumbents and their families over the years. Notably, the Rev. Merv Bowden and his wife, Janice, lived in the rectory with their ten children—and one bathroom!

In 1972, the Tugwell family had the east-end window of the church replaced with a stained-glass window in memory of their parents. This window was dedicated on a very special day for St. Aidan-on-the-Hill. All debts had finally been paid, and the church was consecrated on April 21, 1974. In 1980, the Brash family installed a stained-glass window in the west end of the church, in memory of their son Ronald, who had died in a tragic logging-truck accident.

Evangelical Missions

The Shantymen

The Shantymen’s Christian Association (SCA) was established in Toronto in 1903 by William Henderson. Its mission was to share the gospel and comforts to isolated settlers.

Rev. Percy Wills moved from the Prairies to BC, joined the Shantymen in 1930 and was soon serving along BC’s coast. His first mission trips up the coast were in a dugout canoe, which he rowed along with a partner and a First Nations guide.

Rev. Wills eventually upgraded to the small vessel Messenger II. Then, in July 1946, the Messenger III was launched in Victoria. For many years, Harold Peters, known as “Skipper,” was at the helm. At his invitation, Earl Johnson, known as “Cap,” joined the crew. They both spent many years serving up and down the coast as missionaries aboard the Messenger III.

This era of coastal missionary work came to an end in 1961, as road building and increased airplane routes made settlements and communities more accessible. The Messenger III was sold in 1961, but it remained a west coast icon. In 1991, she was designated a “vintage vessel” by the Maritime Museum of British Columbia.34

Camp Ross

For many summers, kids up and down the coast eagerly waited on docks for the arrival of the Messenger III. I still remember the excitement of those days of the late 1950s and early 1960s. When the Messenger III pulled into the dock, we leapt aboard with our backpacks and sleeping bags. Then we headed across Barkley Sound, in fair weather or foul, sucking in the salty air and barking back at the sea lions.

Whereas other kids up the coast went to Camp Henderson in Quatsino Sound, we were en route to Camp Ross at Pachena Bay.

At Pachena, we disembarked and rode the skiff through the surf onto the waiting sandy beach. My memories of Camp Ross include the smell of the canvas tent, the taste of early-morning syrup-soaked hotcakes, the stories and guitar-accompanied songs around the campfire (along with the flaming marshmallows—I’ve always liked mine burnt) and the gleeful shrieks as we ran into the cold saltchuck to jump the waves. I also remember waiting my turn to bounce exuberantly on the homemade trampoline, created out of interwoven rubber strips from recycled tire tubes.

I think my parents sent my brothers and me off to Camp Ross less for the religious experience, and more for both a fun West Coast getaway for us and a well-needed break for our mom.

I do know that although my dad was a non-religious man, he liked and respected Percy Wills, Earl Johnson and Harold Peters for their goodwill towards all and their West Coast savvy.

Camp Ross continued for many years before being taken over by Coastal Missions and staying open year-round.

Christ Community Church

In 1957, another war-surplus building was moved, this time from the seaplane base to a site across from the secondary school. It would become Ucluelet’s evangelical church. Harold Peters and Earl Johnson of the Shantymen oversaw the operation.

Earl Johnson moved to Ucluelet in 1958 to serve as pastor at the new church. He, wife Louise and three young children lived in half of a rented duplex near 52 Steps. The house rested on pilings out over the harbour. With a two-year-old, and twins not yet walking, Louise was on constant guard to make sure that the kids did not tumble into the saltchuck. Neighbours the Ouras and the Mayedes kept an eye out for the children. They also provided the Johnsons with crab for dinners and instructions on how to prepare it.35 Louise loaded the three children in a wagon and pulled them along the ninety metres of boardwalk to get to the village road. The Johnsons were without a car, but new friends George and Ruby Gudbranson provided road transportation when needed.

George Hardy served as pastor from 1964 to 1976, and his wife Karin was an integral part of the ministry. Rich Parlee also served as pastor. Today, Christ Community still has a large and active congregation. Tofino has an independent congregation called the Tofino Bible Fellowship.

The Driftwood Church

The Shantymen often visited coastal First Nations villages, including Ucluelet East. Meetings at Hitacu were frequently held in the home of Benny Touchie, who extended his living room by five metres to accommodate the attendees. A larger structure was needed, and the parishioners were delighted when a large quantity of two-by-fours washed up on the beach in front of the reserve. The resultant “Driftwood Church” measured eighteen by fifteen metres, and like the other Ucluelet area churches was built by volunteer labour. Services of dedication were held on September 18, 19 and 20, 1964.

Sam Touchie, whom Earl Johnson described as “the recognized leader of the church in their village,”36 reported that although they had no regular minister, visiting ministers often turned up from Victoria, Vancouver and even California.

A New Life for an Old Church

Over the years, St. Aidan’s required continued maintenance and preservation. Gradually, as with so many churches, attendance numbers dropped, and it became progressively harder to keep the church going. Fundraising attempts, including a thrift store in the basement, proved inadequate. There was no miracle at the eleventh hour. In September 2010, St. Aidan-on-the-Hill was deconsecrated and put on the market by the Anglican diocese. Attempts to acquire the church as a museum for our historical society did not pan out.

A local builder named Leif Hagar recognized the structure’s potential. He had done church restorations before, and he also had the patience required to plow through extensive red tape. With skilful and innovative renovations, he repurposed the building while retaining its historic character.

The main floor of the church now houses the award-winning Ucluelet Brewing Company, and the Foggy Bean, a popular coffee roastery, operates from the lower level.

Nostalgia in the Nave

After the brewery opened, my husband and I went there for drinks with some friends. It felt surreal. I tuned out the babble of happy customers and reflected on the past: attending Sunday school, later teaching Sunday school; dusting the pews and aligning the hymnals with my friend Susanne as our moms vacuumed the red carpet and arranged flowers in the brass vases we had polished; the family christenings, weddings, funerals; Christmas concerts in which my daughters were little lambs, little angels, and even a cuckoo clock; and how, in youth group years later, they would climb up inside the bell tower with their friends. My memory drifted farther back; I frowned, remembering how the choir leader had leaned down to whisper, “Just mouth the words, dear,” when I was a small child singing my heart out with the children’s choir. My husband drew me from my reverie. He lifted a glass and said, “We’re sitting right where the altar was—we got married on this exact spot.” I think we’ve found the perfect place to celebrate our anniversary.