Chapter 12: Walking the Telegraph Lines

In its early years, Ucluelet was isolated, and communication with the outside world was sporadic at best. With infrequent mail deliveries, a better system was needed. The answer came in the early 1900s in the form of telegraph lines.

The telegraph system was operated by the Government Telegraph Service, through a head office appropriately situated on Government Street in Victoria. The line from Victoria was linked to Alberni in 1895–96. When routes from there to the island’s west coast were considered, one option was to go along Sproat Lake and Taylor River, through the mountains to Kennedy Lake. From there, it could go south towards Ucluelet, and north along Long Beach towards Tofino. This route, which Highway 4 now basically follows, was vetoed because of winter snow concerns.

Once a different option was chosen, the Daily Colonist of March 30, 1901, reported good progress on the telegraph system. SS Queen City arrived in Victoria with news that surveying the new line from Alberni to Clayoquot was proceeding without delay.

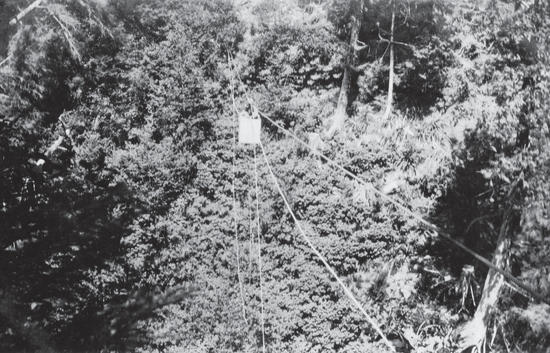

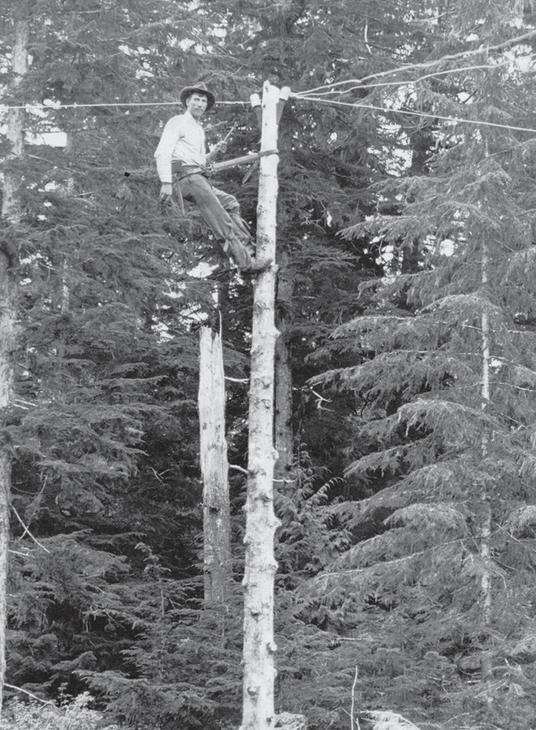

With the surveying completed, the linemen set to work chopping down trees and then topping and trimming other trees to attach lines to. They strung great lengths of heavy iron wire. Materials were delivered by coastal steamer.

The west coast connection branched out from Alberni, with a line on either side of Barkley Sound. One line, completed in 1899, stretched from Alberni to Cape Beale via Bamfield. The line to Ucluelet ran along Alberni Canal to Uchucklesaht and up to Silver Lake, overland to Effingham Inlet, then overhead across the inlet, overland again to Pipestem Inlet, and along the shore from Toquart to Ucluelet. From there, it carried on along Wreck Bay and Long Beach to Tofino, connecting to Stubbs Island by underwater cable. This Alberni–west coast connection was completed in 1902. By 1914, it extended from Clayoquot all the way to Nootka.

The telegraph lines required constant maintenance. Linemen, like lightkeepers, were considered a special breed of men. They hiked the rough trails in all kinds of weather to keep the lines working. Trees regularly blew down in wild west coast storms, breaking the lines. The linemen listened at their stations. If the line was dead, they set out on foot or on water, tracing the line to find the break. Some of them had a battery system to assess whether their repair job had worked. There was more snow then, and they sometimes trudged in freezing temperatures.

The lines were often strung on poles near the shoreline, inaccessible by trail. Some linemen had the use of a launch and would anchor and then row in a smaller boat to the rocky shore and scrabble through bush to tend the lines. Others checked the shoreline by canoe.

Residents up and down the coast used the lines for regular communication and for relaying news of emergencies. The salteries, reduction plants and fish-buying plants relied on the telegraph lines for all their communication, since they had no radios, and mail boats came only every two weeks or so. Because shipwrecks were frequent on the west coast, the telegraph line trails were also life-saving trails. Small huts along sections of line were stocked with telegraph-connection and emergency supplies. For sailors who reached shore from a wrecked ship, finding one of these huts could mean the difference between life and death.

In 1906, after the wreck of the Valencia and its loss of life, the line was extended by thirteen kilometres to connect to the Sechart whaling station. It was hoped that in an emergency, the whaling steamer Orion could be summoned for help.

William Thompson, Ucluelet’s first telegraph operator and lineman, was based in Port Albion. The 1904 BC Gazetteer lists him as telegraph operator and Herbert Hillier as lineman. In 1910, Herbert Hillier is still listed, and his brother Jack Hillier recorded as telegraph lineman at Toquart. The same Gazetteer shows my grandfather, Thomas M. Baird, as lineman at Port Renfrew. They say the life of a lineman’s wife was often isolated and lonely. I think of my Grandma Baird at home with her seven children in their oceanside house in Port Renfrew, waiting for my grandfather to come home from tending the line on wild west coast nights.

It must have been a relief for her when he worked as postmaster, telegraph operator and customs officer, and no longer regularly maintained the lines in foul weather. But worries never ceased, for the 1921 BC Gazetteer lists her younger brother, David Soule, as a Port Renfrew lineman.

Ucluelet pioneer Herbert Hillier helped construct the line between Ucluelet and Alberni and was lineman and agent for over thirty-five years. He, wife Rosa and young sons lived for a time at Curwen Beach, just in from Forbes Island, in a house originally built by Charles Houston Curwen. Curwen had obtained a Crown grant for the isolated site in 1892, but left the area when plans for a proposed nearby development fizzled out.

Herbert tended the line from Effingham to Maggie River, usually travelling by canoe, as his jurisdiction ran mainly along the beach. After a year or so at Curwen Beach, Herbert chose a more sheltered spot, a choice piece of Crown land on a point east of Toquart Bay. Surrounded by water at high tide, it came to be called Hillier Island. With typical West Coast ingenuity, he relocated his house ten kilometres from one site to the other. He disassembled the Curwen Beach house and loaded the pieces on a homemade raft, which he towed by canoe, alternately paddling and sailing with a “blanket sail.” At Hillier Island, he unloaded the pieces and reassembled the house.

It was an isolated existence. Norah Thompson recalled that as a girl she once went with her father, William Karn, to spend the summer on Hillier Island when Mr. Hillier had to be away. She said it was the most boring summer of her life, as there was nothing to do out there but read. Norah wasn’t keen on boating, as she was prone to seasickness, but she was convinced in later years to revisit the island with her daughter Ann and son-in-law Wally Branscombe. The house had long since collapsed, but in the ruins they found an old telegraph lineman manual, which Norah brought home as a souvenir of that long-ago summer on Hillier Island.

Herbert’s brother Jack came to Ucluelet in 1906, working as a telegraph lineman and operator. He lived at Toquart, maintaining the line halfway to Ucluelet and halfway to Kildonan. (In those days, Kildonan was a bustling town, essential to the fishing industry.) Jack also tended the line out to the Sechart whaling station. Life as a telegraph lineman required the strength and stamina to work often through the night and ford chest-deep glacial rivers to reach downed lines.

When William Thompson moved his family to Cape Beale to become lightkeeper, Herbert Hillier took over as telegraph operator. Herbert and Rosa moved their family into the Port Albion house built by William Thompson, and raised their four boys there. When Herbert retired after thirty-five years with the telegraph service, he was awarded a King George V Silver Jubilee Medal.

Herbert’s eldest son Bill later worked the same route his father had, living out on Hillier Island and coming home to Ucluelet on weekends. Upon reading Bill’s diary, his son Frank noticed that when Bill walked or canoed along the lines, he always took a rifle and fishing lines. Although Bill once shot a cougar as it charged him across the mud flats, the gun was not just for protection. He shot deer, ducks and geese. He also caught fish; one entry in Bill’s diary records his catch of forty trout.1 Frank reflected that licensing officials today would not be impressed, but back then it was survival mode. “I don’t think the Federal government was overly generous in their salary,” so the linemen hunted, fished and grew small gardens. They got most of their food off the land.2

In 1937, with Bill now telegraph operator at Ucluelet, Ron Matterson took over as lineman out of Ucluelet. World War II brought an increased emphasis on communication. Ron’s maintenance of the line between Ucluelet and Tofino would eventually become easier when the war spurred the creation of a road between the towns. For a time, he continued to walk the line, but he then had the use of a car and later a government truck to travel the rough road.

The lines going the other direction were what his wife, Ann, called “the dangerous part and the busy part.”3 From Ucluelet, Ron’s section stretched almost to Maggie River. Much of his area was exposed to wild winds, which frequently blew trees down onto lines. “He had some pretty close shaves out there,” Ann said.4Ron had no launch and twenty kilometres of rough terrain to hike. Sometimes, in urgent cases, he chartered a boat to reach downed lines quickly.

When hiking rocky shores and beaches, Ron collected treasures. He once found a wheel with Japanese markings, which he thought might have come off a plane. He found many glass balls, coveted fishing floats that drifted across from Japan. Ron lined them up on a log, planning to pick them up on his way back. They’d often be gone when he returned. Sometimes he found tinned food, such as pemmican, and stored it in the lineman cabin at Curwen Beach. Ann said he found “things that would have kept a man going for days and days.”5

Ron was given an assistant during his last two years as lineman. After ill health forced Ron to retire in 1952, a new employee said they would only do the Ucluelet to Tofino route, not the more arduous section from Ucluelet to Maggie River. The government decided that it was actually a three-man job and sold out to a private company soon after.

Shared News

The Rural Telephone Company, formed in 1910, was the first of its kind in BC. The settlers all bought shares and telephones. Before that, one line connected just three homes around Ucluelet Harbour.

With the new company, one line connected the whole town. People had their own combination of rings. With this shared line, eavesdropping was discouraged, but it happened. Phyllis Binns recalled that at times telltale background noises, such as the ticking of a particular clock, could be heard, indicating a lurking eavesdropper. My Uncle Tom told the story of once saying over the phone, “Be careful what you say about that. ‘Mrs. Such-and-Such’ might be listening in.” At this point, “Mrs. Such-and-Such” was heard to say indignantly, “I am not!”

One long ring signalled an emergency, and everyone got on the line to hear the news. During the war, Herbert Hillier gave community updates over the phone line. Phyllis Binns described the one long ring as the “Clarion Call,” and nicknamed Mr. Hillier, sharer of important news, as the “Long Ringer.” Sometimes his calls were about true emergencies, sometimes they relayed important updates on such things as the opening of fishing season, and sometimes they were the means to plan an entire community event over the phone.

Norah Thompson (née Karn) and Enid Hutchings (née Hillier) worked in the Dominion Government Telegraph and Telephone office. When it was sold, the telephone portion at Ucluelet, Port Albion and Tofino et cetera became the BC Telephone Company. Norah continued to work for them. Other employees included Noreen Taylor and Ruby Gudbranson. The telegraph portion at Ucluelet and Tofino became Canadian Pacific Telegraphs.

Now, here on the west coast of Vancouver Island, we have the latest technology, including cellphones and high-speed internet. West coast historian R. Bruce Scott described the communication of yesteryear with great eloquence in his article entitled “Simple Telegraph System”: “The old telephone lines may still be seen, draped from tree to tree, or on sagging poles along the shoreline. Lines that once carried the gamut of human emotions now lie broken and unattended, grounded and short-circuited, by-passed by technological progress.”6