Chapter 5: Of Whales and Whaling

Whales are tied to the spiritual and cultural values of the Nuu-chah-nulth people, who sustainably hunted

ʔiiḥtuup (whales) for thousands of years. Nuu-chah-nulth whaling was done with acknowledgement and gratitude, and an understanding of the need to maintain a balance with nature.

The Nuu-chah-nulth people hunted m̕aaʔak (grey whales) as they passed along the west coast on their spring migration. They sometimes hunted the greys on their winter migration south, but this involved paddling farther offshore in wilder weather. They also hunted humpbacks, which could be found year-round in the Barkley Sound region.

First Nations whale hunters followed meticulous physical and spiritual preparations, including cleansing rituals. They then travelled far offshore in a whaling canoe, typically between eight and eleven metres long.1 There were usually between six and twelve crew members in a canoe, including the harpooner in charge of the hunt, who was traditionally the Chief. Smaller canoes commanded by younger kin of rank often accompanied the main canoe. The heavy harpoon staff, usually made from two lengths of yew or fir wood scarfed and bound together, had a harpoon head made of a large, sharp mussel shell attached between two antlers or bone barbs.2 The harpoon was attached to a long line made from deer sinew or rope made from cedar or spruce-root. Sealskin floats were spaced along the line. The floats had mouthpieces attached for inflation, and uninflated floats were carried aboard the canoes as spares. When whales were harpooned, the floats prevented them from diving underwater. Once a whale was exhausted, the hunters moved in with their short spears for the kill.

The pursuit and killing of the whale was a long and dangerous process. After the whale died, one of the crew dove in and cut a hole through the upper lip and the jaw, tying the mouth shut to prevent water from filling the whale carcass and sinking it.3

Then the hunters had the arduous task of towing the whale to shore, singing as they paddled. Their return was cause for celebration, as the whale carcass was divided up and shared among the people, with portions distributed in order of rank. Ceremonies featured special songs honouring the whale. The Nuu-chah-nulth harvested only what they needed and did so with appreciation and respect.

All that changed with the arrival of European whaling technology and attitudes. It was a sign of things to come when Samuel Foyn of Norway visited Victoria in 1898, with the message “I am convinced that your waters are rich in whales.”4 Foyn, nephew of the inventor of the shot harpoon, advocated the use of steam vessels and harpoon guns. He promoted whaling as an enterprise, saying, “In spite of numerous temptations, I will never do anything else but whale. I live on the excitement and the big chances of rich reward.”5 Foyn also said it would not matter if whaling was based in Vancouver or Victoria, “as a whaler is seldom in port. His home is on the sea.”6

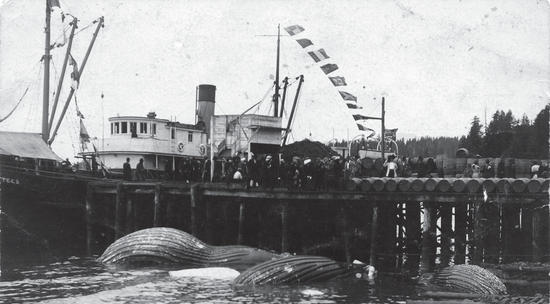

Commercial whaling began on the west coast of Vancouver Island in 1905, when three men established the Victoria Whaling Company under a nine-year licence. Brothers Reuben and Sprott Balcom, along with their partner Captain Grant, were based in Victoria. Their company was also referred to as the Pacific Whaling Company. They set up four whaling stations. The first, at Sechart in Barkley Sound, opened in September 1905.

Sechart is named after the c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht First Nation), whose Traditional Territory was in Barkley Sound. The name c̓išaaʔatḥ relates to their skill as whalers.7 As Nuu-chah-nulth whalers, they hunted the mammals sustainably and respectfully. This would not be the case with the new inhabitants of Sechart.

Unable to find a vessel serving their purpose, the owners of the Victoria Whaling Company had a steam chaser boat called the Orion built in Norway. Between the steamboats and large harpoon cannons, the whales didn’t have a chance.

A 1907 newspaper article described an incident involving one of the steamboats, the St. Lawrence, where “a bomb fired into a whale exploded while the mammal, which had dived, was directly beneath the vessel. The explosion, which killed the whale, shook the vessel severely, but did not damage her.” The article also recounted another instance where a big “sulphur-bottomed whale towed the steam whaler for twenty-five miles before he succumbed.”8

Sechart was both a whaling station and a processing plant. Government rules decreed whale carcasses had to be processed and disposed of within a twenty-four-hour period. To accomplish this, the company purchased machinery designed by German engineer Ludwig Rissmuller, paying him with shares in the company.

The business was initially considered a success, with large quantities of oil shipped to Glasgow and fertilizer to Honolulu. Japan purchased oil and whale meat. In 1908, these magnificent mammals were valued at between $400 and $800, with approximately thirty-five barrels of oil pumped from each whale head.9 In 1909, one of the largest whales ever captured—more than twenty-six metres in length—was harpooned in Barkley Sound and the carcass taken to Sechart.

The smell from Sechart was said to rival the sulphurous stench of the Alberni pulp and paper mill. One Alberni resident stated: “A whaling station really hums, in fact you can almost lean against the smell, when they are really going good.”10 En route back to Victoria, coastal steamers stopped at Sechart to load whale oil and fertilizer. Passengers who could handle the stench would disembark to observe the workings of the plant. There is a record of a young woman slipping in slime at the top of the whale chutes and sliding down into the water.11 Hopefully, someone loaned her dry clothing for the boat trip home!

The coastal steamers sometimes offered whale meat on the shipboard menu, and the Victoria Whaling Company published a recipe booklet of twenty “tried and true” recipes for whale meat, including one for Sechart Salad.

Scientific Study

In July 1908, R.C. Andrews from the American Museum of Natural History Society of New York City came to the West Coast. His mission was to study Pacific whales and compare them with Atlantic whales. Andrews visited the whaling stations at Sechart and Kyuquot, and went out with the whalers, photographing whales “feeding, sporting, and being taken by the harpoon.”12 He busily recorded measurements of taken whales to compare with the Atlantic statistics he had amassed back in New York.

While in Victoria, Andrews hosted an exhibition in Gorge Park, displaying a twenty-six-metre skeleton of a sulphur bottom whale (blue whale), reported to be the largest on show anywhere in the world. The whale had been killed off Vancouver Island’s west coast, having “made a tremendous fight for his life.”13 The newspaper exulted: “The tourist visiting our city will find something in Victoria which they cannot find anywhere in the world, and whoever wants to see the largest creatures of creation has to come to Victoria.”14

An End to Whaling in Canada

The whaling industry had its critics. A newspaper article in 1910 denounced the industry, stating that “the shot harpoon was invented in 1870 by Svend Foyn, a Norwegian, and is the most deadly and extraordinary weapon ever devised by man for the pursuit of helpless animals,” and went on to opine that “this revolting butchery…is carried on solely for the satisfaction of human greed, and apparently will be stopped only by the extinction of the yet remaining whales.”15 An article in the Vancouver Daily World on January 6, 1912, concurred, calling for restrictive measures before it was too late. Warnings were ignored. A 1918 newspaper article extolled whaling on the BC coast and described “modern-day whale fishing” as an “exciting experience.” On an even more extreme note, the article stated: “It is wonderful to note the fatal effect of one of these explosive bombs in the body of such a huge animal.”16

Given the prevailing attitude of greed and the technology for slaughter, whale numbers declined rapidly. Records show that between 1908 and 1917 Sechart processed 2,244 whales, most of which (1,869) were humpbacks.17 The owners, having virtually eliminated their “product,” cancelled their whaling licence for Sechart on February 20, 1918. The Cachalot station at Kyuquot closed in 1925.

Vancouver Island Fisheries leased the buildings at Sechart for a herring packing plant. Then, in 1926, the Millerd Fish Packing Company bought the old Sechart whaling station to manufacture oil and fish meal from dogfish and pilchards.

Whaling carried on after the Sechart station closed. The Province newspaper of September 20, 1918, reported great activity at the coastal whaling stations, with an exceptionally large catch. A brief note in the Province on December 20, 1918, stated: “The season’s catch of a coast whaling company is given as 999. It would have been foolish to leave the 999 to chase after one stray whale just to make a round number.”

The Victoria Whaling Company shut down in 1943, which is considered the end of the first era of modern whaling in BC. The second era began after World War II. A BC Packers group continued whaling, shifting from oil and fertilizer production to edible whale meat export. It was not until 1946 that an international whaling convention, signed by Canada, established guidelines to protect the creatures. Because the Department of Fisheries had no jurisdiction beyond territorial waters, some whaling continued off BC’s shores. Several BC entrepreneurs bought up old whaling ships and equipment, but their attempts didn’t last long.

In 1967, whaling finally ended on the West Coast. By then, BC companies had killed and processed approximately 25,000 whales. The destruction was catastrophic. At least 5,638 humpback whales were killed off British Columbia from 1908 to 1967, with the highest catches taking place before 1917.18 The North Pacific humpback came close to extinction but is now making a comeback. When a right whale was seen off Haida Gwaii in 2021, it was the first sighting in BC waters since 1951.

Eugene Arima and Alan Hoover, in their 2011 book The Whaling People of the West Coast of Vancouver Island and Cape Flattery, write that the decimation of whale populations by the commercial whalers meant “the virtual death of traditional whaling by the Whaling People.” As the population numbers recovered, some First Nations made their case for regaining their traditional rights to harvest whales, which they saw as a means of sustaining both body and spirit, and as part of revitalization of their culture. On May 17, 1999, the Makah Tribe of Washington state harvested a grey whale. Their main opposition was from animal-rights activists. In June 2024, the Makah were authorized to resume ceremonial and subsistence hunting of up to twenty-five grey whales over a ten-year period in US waters (two to three whales yearly) through a permit process.

On Vancouver Island, the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ (Ucluelet) and t̓uk̓ʷaaʔatḥ (Toquaht) were two of the five First Nations to sign the Maa-nulth Treaty in 2006. In so doing, they gave up their right to hunt grey whales for twenty-five years.

Sechart Transformed

The Sechart whaling station found new life as the site of a kayaking lodge. Owned by the Lady Rose Marine Group, it was run for many years by Henk Holten and Karey Monrufet, and was a delightful place to use as a base to kayak in the Broken Group Islands. My husband and I always felt that even though we were just hours from Ucluelet by boat, we were truly away from it all.

Sechart Lodge was our ideal getaway, where we could paddle all day, then return to a hot shower, a delicious meal and a comfortable night’s sleep (with the bonus of visits from Putt-Putt the cat). One memorable day, Henk ferried our group to the outer islands in the fog aboard his thirteen-metre aluminum boat, the Karey M (named after his wife Karey). We had an epic paddle around islands in the fog, and a long paddle back to the lodge as the fog lifted.

Paddling with Whales

My kayaking years on the West Coast have brought treasured whale sightings. One day at Grice Bay, I kept what I deemed a respectful distance from several grey whales. One, unbeknownst to me, took a very long dive and emerged right beside my kayak. It then dove again, coming up on my other side. I rode the resulting mini-tsunami with an exultant surge of adrenalin! Another time, after a group of us exited Ucluelet Harbour in our kayaks, heading towards Toquaht, the friend ahead of me stopped suddenly as what she had thought was a large rock surged upward in front of her. We detoured around the massive grey whale, landed on a nearby sandbar, and watched, mesmerized, as the grey fed while hugging the coastline.

The purest magic of all happened at the end of one all-day paddle in Barkley Sound. A humpback whale accompanied us back towards Sechart Lodge. Once we were out of our kayaks and on deck, the massive mammal proceeded with an exuberant show of diving and breaching. At Sechart, once the site of a whale processing plant, this display was pure joy to behold.

When Brooke George, the owner of the Lady Rose Marine Group, died in a tragic 2006 accident, the business was sold. Sechart Lodge became Broken Islands Lodge, and it continues to be a place for an “off-grid” experience, accessible only by boat.

Whale Watching

Although whaling was a thriving industry starting around 1907 along BC’s west coast, some individuals got caught up in the magic of whale watching. A 1908 Vancouver newspaper article waxed eloquent about the experience: “Talk about your sport and big game hunting; it may be all very exciting to chase grizzlies and decoy the lordly moose, but if you want real sport, with real ‘big’ game, then go hunting whales with five large cameras and a ten-ton yacht.” The party of eight aboard the yacht the Ella May relished the opportunity to photograph “a couple of festive whales…playing leap frog with each other in their native element.”19

With the intelligence and uniqueness of these amazing mammals increasingly recognized, whale watching has become a popular pastime. A sighting is always thrilling, whether it’s a spout in the distance or spectacular fluking, spy-hopping or breaching.

Brian Congdon of Subtidal Adventures knows all about whale encounters. He and his wife, Kathleen, started their business in 1978, making it Ucluelet’s oldest nature-tour enterprise. Brian initially offered dive charters, soon switched to general nature tours, and then, around 1982, was drawn in by the presence of the ever-magical whales. His first whale-charter sighting was right at the mouth of Ucluelet Harbour. Initially, the whales he saw were all grey whales. The humpback whales were all offshore. Then, when pilchards returned, many humpback whales showed up regularly in Barkley Sound, especially in the Sechart area.

An avid nature photographer, Brian found that his photo collection was a helpful way to identify individual whales and share their status and location. This enhances knowledge about the habits and longevity of whales. Brian is now recognizing generations in whale families. Many whales are distinguished by their unique markings. Sadly, the markings sometimes come from encounters with boats; for example, one whale is nicknamed “Props,” owing to multiple scars on its back from a boat propeller. Surprisingly, Props shows no fear of boats.

Lynette Dawson, a local whale-watching skipper and guide, has worked for several local whale-watching businesses and been on the water for twenty-plus years. She takes tours out into Barkley Sound as well as up the coast as far as Long Beach. There are plenty of sightings of grey whales on their annual spring migration, and lots of humpbacks, especially in the spring. It is less common to see killer whales, and unusual to see minke and fin whales.

Local whale watchers follow specific guidelines put in place to protect the whales. They care about them, look out for them. Sadly, a high percentage of the whales they see show signs of previous entanglement in fishing gear. Lynette once encountered an entangled whale while out with a tour group. She needed to monitor the whale’s location until the Department of Fisheries and Oceans’ (DFO) trained team could come to attempt to free the whale, and so she asked the passengers if they had anywhere they had to be. They all were in favour of staying with the whale for what turned out to be seven hours, until the DFO arrived. The whale was set loose and swam away with a new name—“Freedom.”

Protection and Prognosis

The scientific name for the grey whale is Eschrichtius robustus. A robust existence is what we wish for all species of whales. But they have many human-caused threats to contend with.

Local First Nations, as well as other groups and individuals, share a common goal to promote the health of oceans and protect marine wildlife and ecosystems. Dr. Jim Darling, a pioneer in cetacean studies, founded the West Coast Whale Research Foundation in 1981, and has led independent whale research programs for over thirty years. The Strawberry Isle Marine Research Society (SIMRS), founded by Rod Palm in 1991, has a strong education component, including its interactive Build-A-Whale program. The SIMRS has monitored cetaceans and helped rescue whales and other marine mammals from disastrous situations. In December 2023, the SIMRS was amalgamated into Ucluelet-based Redd Fish Restoration Society, reflecting their shared commitment to marine stewardship.

Parks Canada monitors marine mammals in the waters of the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve. They also participate in a collaborative photo-ID program co-ordinated by the US-based Cascadia Research Collective, tracking individual grey whales.

The status of whales continues to be closely monitored, and their risk designation is reassessed as numbers fluctuate. Grey whales, humpbacks and all other cetaceans continue to face a variety of threats, including vessel strikes, entanglement in fishing gear, excess sound disturbance, toxic spills, habitat alteration and the effects of climate change.

Sharing the News

When whales venture into Ucluelet Harbour, we residents have our own communication system. If a phone call shares news of kakaw̕in (killer whales) in the harbour, I phone someone else before dashing to the beach as the word continues down the line. Grey whales rarely come into the harbour, although one year, when there was a substantial herring bloom, we were treated to sightings of a magnificent grey right in front of our house. Now, with social media, news spreads like wildfire. Facebook will buzz with “a pod of killer whales passing the lighthouse, headed into Barkley Sound,” or “three humpbacks, heading past OJ’s lookout on the Wild Pacific Trail!”