Chapter 24: Tourism Then and Now

Although Ucluelet and environs have deep resource-based roots, tourism goes back many years. Newspapers in the early twentieth century praised the area’s beauty, often focusing on nearby Long Beach and Wreck Bay: “The two bays together form one of the most remarkable sea beaches in the world and are without rivals on the whole Pacific Coast. The sand has been hammered by the ocean waves through countless centuries, until it is almost like a pavement. Here is certain to be one of the greatest summer resorts.”1

Sightseeing excursions on steamships were a popular draw. West coast trips aboard the Princess Maquinna in the 1920s and 1930s were in such demand that the Princess Norah was built partly to accommodate more tourists. The west coasters loved their Princess Maquinna and were upset when she was relocated to the Alaska route. The beloved ship reclaimed the west coast route for the summer crowds.

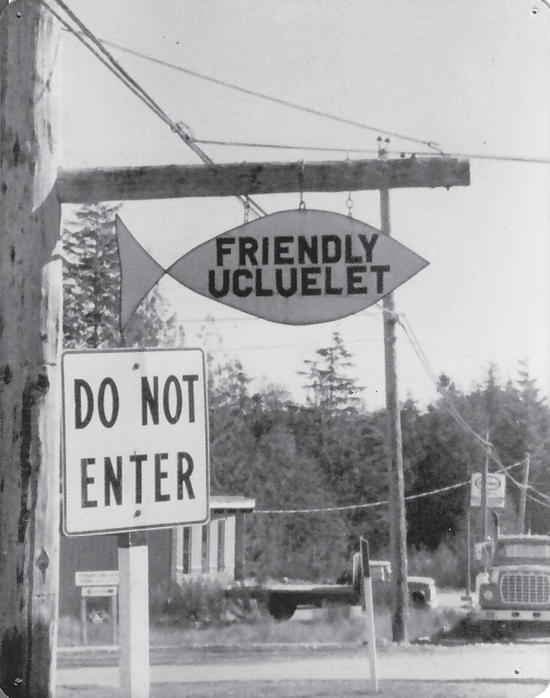

A Daily Colonist article of December 3, 1922, proclaimed: “There are few prettier villages than Ucluelet.” Upon disembarking, tourists visited George Fraser’s renowned gardens, leaving with a complimentary bouquet or sprig of heather.

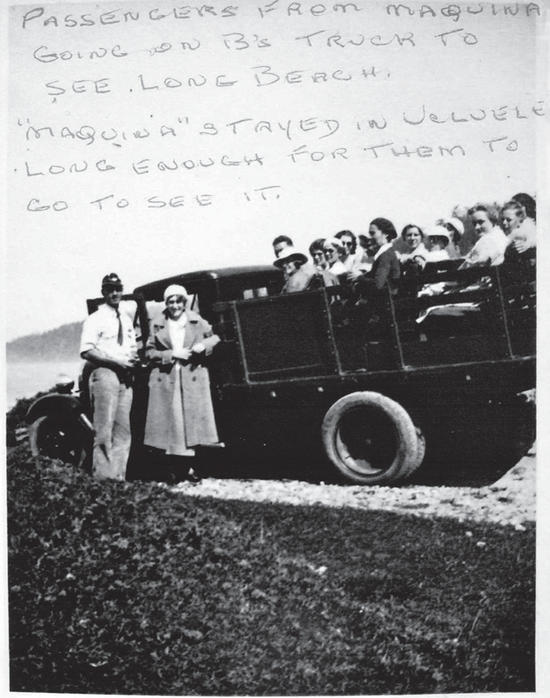

Another option was a quick excursion to Long Beach in Basil and Mary Matterson’s tourist truck—hopefully, the weather co-operated, as the truck was open to the elements, with up to fifteen people in seats set up on the flatbed. The truck bounced over the rough road to Long Beach and back during the Maquinna’s sojourn in Ucluelet Harbour.

Tourism promotion featured nuučaan̓uł individuals and their artwork. Ads included pictures of totem poles and woven baskets. Today, we understand this to be blatant exploitation, especially since First Nations people, when travelling aboard the Princess Maquinna, had to remain on the outside deck, or in the hold during rough weather.

August Lyche’s large family home became a popular hotel aptly named the Bayview Lodge. William and Sarah Thompson ran it for two and a half years. Their daughter Sheila Mead-Miller later remarked that her parents knew nothing about running a hotel. “They quite enjoyed it, but it wasn’t a money-making concern. Because they hated to give anyone their bill.”2 During the Depression, most people were financially strapped, and the clients at the Bayview Lodge tended to be business people who could afford excursions up the coast. They often stayed at Ucluelet for a week. “I remember one man was…a Kellogg from the corn flake people…Lepages Glue, there was the father and the son.”3

When the Thompsons gave up running the hotel, Alma Littleton (née Lyche) and husband Stan moved back to Ucluelet. Alma later told Sheila, “You know, I often wonder why we took over that hotel. I should have had my head examined.”4 The hotel was jam-packed through the war years, and Alma was run off her feet, but she managed. As Sheila Mead-Miller explained, “if you want anything done, you always ask a busy person.”5

The Ucluelet Lodge

When Bill Fraser and Henry Bonetti returned from serving in World War II, they built the Dell Café, named after Bill’s daughter Delores. Bud Thompson bought Henry Bonetti’s share in the business, and Fred Rhodes joined the partnership. The Ucluelet Lodge was built onto the café, and the three partners opened it in July 1950. Bill and his family lived in the hotel until 1953. The business provided rooms for visitors and a chance to visit the local drinking establishment. The bar was a popular gathering place for loggers and fishermen after long shifts, “but only the brave would drink the draft beer.”6

Martin Marangoni started working at the Lodge in 1956, slinging beer two years before he reached legal drinking age. He continued working there off and on for forty years. Martin recalled many characters, including the fellow who got barred for frequent misbehaviour and then got served when he came back disguised as a woman.7

The Frasers sold the building in 1960. Later owners included Ron Burley, Rod Hardy and Ted Walker. When logging and fishing took a downturn, the business struggled, changing hands often over the years. In February 2010, the Lodge closed its doors, and many bemoaned the end of an era.

But the gathering place was revitalized when Officials Sports Lounge, already sharing part of the building, knocked down the dividing wall and took over 60 percent of the floor area. The building’s owner rented out the remaining space for retail. Officials’ owners Dale Holliday and Ray Godfrey maintained a dance floor and hosted bands, dinner theatre and fundraising events. Then, in 2019, to much local disappointment, Officials closed after a decade of business. In a sign of the times, a cannabis shop opened in the renovated building.

Other older lodgings continue to accommodate tourists. The duplexes of the tastefully remodelled Little Beach Resort were barged into Ucluelet before there was a road, providing housing for tourists and local workers in what was originally called the Blue Bird Auto Court.

Despite early forays into tourism, the economy was based on resource industries. When mining, logging and fishing took a downswing, the focus turned to tourism. Some locals made a living on the water, through fishing charters, whale watching and nature cruises, or kayaking tours. Many worked in the hospitality industry, in restaurants, hotels or bed-and-breakfasts. As more tourists arrived, gift shops and art galleries burgeoned.

When Pacific Rim National Park was established, some popular tourist businesses had to leave. In an article decrying the federal park’s closure of the Wickaninnish Inn, writer Charles Oberdof stated: “If all the hotels are turfed out of the park, the nearest place to stay will be Port Alberni.”8 Although the closure of the original Wick Inn was a major disappointment, more options in Ucluelet and Tofino became available to accommodate the groundswell of tourists. Hotels and motels, B & Bs and campgrounds, all added to the local economy.

The Canadian Princess

This sixty-nine-metre vessel was an iconic sight in Ucluelet for many years. Originally a hydrographic survey vessel called the William J. Stewart, she was bought by the Oak Bay Marine Group in 1979, refurbished and towed to Ucluelet to operate as a floating fishing resort, hotel and restaurant.

Renamed the Canadian Princess and settled in the Ucluelet Boat Basin, the ship was a base for the Princess fleet of whale-watching and fish-charter boats. Oak Bay Marine Group founder Bob Wright had found a niche, flying in avid sport fishers from the US as well as Canada. Many locals skippered and crewed the thirteen-metre Princess boats, while others staffed the floating restaurant and hotel. Although the resort also offered onshore accommodation, the novelty of the floating hotel was a strong draw. The Islander magazine of July 27, 1980, described it as “offering a unique wilderness experience.”

The Canadian Princess employed up to 150 people (including those working in her associated restaurant at the Wickaninnish Inn in Pacific Rim National Park). Then Bob Wright closed the Canadian Princess, along with two other Vancouver Island resorts. Dianne St. Jacques, service manager on the Canadian Princess for many years, was Ucluelet’s mayor at the time, and commented: “It’s sad but change is something that’s a constant for all of us and we have to embrace it and move forward.”9

The forty-six-unit onshore lodge was sold and continues to offer centrally located accommodation. In March 2016, there was a shipboard ’20s-themed farewell party, the “Great Gatsby Casino Night.” Dressed as flappers and gangsters, partiers gathered for the last hurrah. Later, some of us toured the ship from stem to stern, visiting her historic engine room.

“She was a big milestone when she came in and it will be a big milestone when she pulls out,” Mayor St. Jacques said.10 And so it was. Locals thronged wharves and shoreline to wave farewell. Small boats followed alongside and astern as the majestic white ship was towed out of the harbour, headed for her final resting place in Vancouver. There, she was stripped and dismantled. Mayor St. Jacques reflected that it was “an opportunity for new businesses to step in and pick up that slack.”11

Norm Reite’s Island West Marina offered the full spectrum for fishers, enhanced by a lodge, a campground and the Eagle’s Nest pub-restaurant. Businesses such as Reef Point, Roots Lodge, Whiskey Landing, Tauca Lea (now Water’s Edge) and Hollywood star Jason Priestley’s Terrace Beach Resort offered seaside getaways. In 2008, Black Rock Oceanfront Resort opened, offering 135 rooms, a spa and a restaurant, lounge and wine cellar with panoramic views of the oft-wild Pacific. The resort provided more employment options and, like many other businesses, gave back generously to the community.

The Ucluelet First Nation also recognized tourism business opportunities, building Wya Point Resort, which was described as adding “a new element to the region, the promise of First Nations’ cultural tourism amid a beautiful setting.”12 Starting with a small campground, the nation added yurts with “a million-dollar view over the rocky shores.”13 At the junction, the UFN also established businesses for surf rentals and lessons, refreshments, bike rentals and tours.

“Left at the Junction” is the name of a popular Ucluelet band and also reflects a growing trend, with an ever-increasing number of visitors turning left at the junction, towards Ucluelet, rather than making that right turn for Tofino. Tofino has historically been the media darling, with Ucluelet described as Tofino’s “ugly stepsister,”14 and “the grimy Cinderella down the road.”15 A bold headline proclaiming “a clash of cultures” described the two towns as “far-from-identical twins sitting 42 kilometres apart at the ends of two peninsulas that look like righteous fingers pointing in the opposite direction.”16 Going on to describe Ucluelet as a former “brawny economic powerhouse,” the writer reflected on the protest movement that was “a public relations defeat for the culture of the chainsaw.”17 Tofino residents interviewed by the reporter decried the shaved mountaintops of Ucluelet while lamenting the drawbacks of their booming community. Activist Valerie Langer described the lack of control felt in Tofino: “We can’t keep up with the pace of development.”18

The logged mountains of Ucluelet greened up, and eco-tourism plans blossomed. But, as then mayor Bill Irving put it, “We’re trying to maintain the working-class ambience of Ucluelet,” where fishermen, loggers and tourist operators can all be part of the community.

In 2010, Ucluelet got a nod from the New York Times, in its article choosing Vancouver Island as one of “the 31 Places to Go in 2010.” The edition praised the Wild Pacific Trail and the “folksy fishing village called Ucluelet,” adding: “I’ll bet they’re smiling in the tourist offices of Ucluelet, which has long taken a back seat to its more glamorous sister village Tofino.”19

They may have been smiling, but they were also struggling to keep up with the groundswell of visitors who turned left at the junction. A Victoria newspaper article in 2014, “No Room at the Inns in Ucluelet,” quoted then Ucluelet Chamber of Commerce director Sue Payne as saying it was the first time Ucluelet “had hit its tourism capacity in about a decade.”20 The trend continued.

The sport fishery also reeled them in. In 2020, Ucluelet was the only place in BC to make FishingBooker’s list of best fishing destinations. It was Ucluelet’s second year on this prestigious website that ranks fishing trips across the globe. Lara Kemps, then manager of the chamber of commerce, credited local sport fishing guides and operators: “Our fishing charter companies have such a sterling reputation because of not only their passion for their work, but also for the area in which we live and play.”21

In 2022, Ucluelet’s publicity ramped up even more. Among 128 rivals in a contest run by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation for “BC’s best small town,” Ucluelet came in second, narrowly losing to Kimberley. Further positive press came in 2023 with a Maclean’s magazine article titled “The Great Escapes: 10 Places to Visit in Canada Right Now,” in which Celeste Moure described Ucluelet as “the storm-swept hideaway” with “gorgeous squalls…enchanted forests…and a pretty little harbour.”22 Of course, the irony is that the more publicity we get, the less of a hideaway we become.

The Wild Pacific Trail

In 1971, Ucluelet public health nurse Myrt Saxton, a volunteer in many community groups, sponsored an Opportunity for Youth summer program in which she supervised five young people building a trail in He-Tin-Kis Park. Further work was done on the He-Tin-Kis Trail, a boardwalk loop built through a contract with the District of Ucluelet. Dave Manuel did a lot of the work, along with other locals. A section is incorporated into the present Wild Pacific Trail, and other parts of the old boardwalk are now blocked off.

“Oyster Jim” Martin had a dream and made it a reality. It didn’t happen overnight. That Ucluelet’s Wild Pacific Trail exists today is a testament to his drive and tenacity. When Jim Martin arrived in Ucluelet in the summer of 1979, he earned the moniker OJ because of his livelihood in oyster farming. As he explored the outer coastline and fished off the rocks, OJ soon envisioned a trail along the rugged coast. “This was something that had to be made accessible to the whole world.”23 Around every corner he saw “streaming postcards” and potential for what he called the eighth wonder of the world.

Bill Irving, Ucluelet’s mayor from 1990 to 1997, reflected that when OJ came forward with his vision, logging and fishing were still booming, and people were not thinking about tourism. OJ saw not only the present but the future. All who are acquainted with him recognize his charisma. The Edmonton Journal described OJ’s “no-guff kind of charm.”24 That, along with inventiveness, hard work and know-how, was a big-time bonus for Ucluelet. (OJ attributes some of his know-how to his thirteen years as a Scout leader.) He originally pitched the name Pacific Rim Trail. When that was vetoed, he called it the Wild West Trail. Access to a sizable grant entailed coming up with a different name; the day the Wild West Trail Society was registered, OJ orchestrated a quick name change to Wild Pacific Trail.

The grant was supplemented with fundraisers like hot dog sales, but more was needed. OJ begged for money and supplies from municipalities and businesses, and through what he described as “magnanimous shows of support,” he came up with the requirements to complete the initial project. The War in the Woods meant out-of-work loggers were in a retraining program, which covered the $17,000 for their wages to work on the trail. The Lighthouse Loop section opened to much fanfare in 1999.

Accessing land for the trail was challenging. When officials said no, OJ kept on fishing for a yes. Charles Smith, former director of real estate for MacMillan Bloedel Ltd., repeatedly deflected requests for access to build trail on forestry land. Then, as logging and fishing bottomed out, Smith recognized the need for tourism to boost the economy.

OJ got his okay for the next phase of the trail from Big Beach to the highway. Funding for this 2002 section was managed by the Central Westcoast Forest Society (now the Redd Fish Restoration Society). Clayoquot Forest Engineering was contracted to build the trail, and under site supervisor David Edwards it did the surveying, some design work and construction, with many locals involved in the work. OJ added artists’ loops to take advantage of the spectacular ocean views.

In 2013, the Ancient Cedars and Rocky Bluffs section opened. Further bonuses included interpretive trails, connector trails and more spectacular viewpoints.

OJ’s dream is supported by the dedicated volunteer board of the Wild Pacific Trail Society (WPTS), a registered non-profit group founded in 1999. Long-time WPTS president Barbara Schramm provides a strong and steady hand at the helm. As well as trail building and enhancement, the group provides trail-related educational programs. The District of Ucluelet now manages trail maintenance, but OJ continues to create artistically designed viewpoints. He and the WPTS board pursue the goal of extending the trail to connect to Wreck (Florencia) Bay and Long Beach.

First Nations Elder Vi Mundy, a long-time Trail Society board member, stated she was impressed with the respect shown by the Wild Pacific Trail Society for the First Nation lands, cultures and history. She spoke of the rejuvenating benefit of being on the trail, saying with her typical insight and humour: “There is no Wi-Fi in the forest, but you will find a better connection!!”25

Ucluelet Aquarium

As the first catch-and-release aquarium in Canada, the Ucluelet Aquarium has been a strong tourist draw since opening as a mini-aquarium in the spring of 2004. Founder Philip Bruecker started the Ucluelet Aquarium as a pilot project. It proved so popular that a larger, more permanent structure was needed. Volunteers, businesses and the municipality came together to realize the dream, and the new Ucluelet Aquarium opened next to the Whiskey Dock in May 2012. The original mini-aquarium building was moved to Campbell River. Bruecker’s vision spread not only across Vancouver Island but around the globe. In 2019, the Ucluelet facility held the first ever mini-aquarium conference, sharing information about their successful catch-and-release model with eager visiting delegates.

The exhibits captivate adults and children alike, and the annual release day to return the critters to the sea is a festive event. The aquarium continues to thrive, as employees and volunteers promote conservation and stewardship of the oceans.

Crowd-pleasers

The Ucluelet Chamber of Commerce and Tourism Ucluelet are two groups promoting local tourism. Yearly events, such as Whale Fest, the Edge to Edge Marathon, and the Van Isle 360 sailing race around Vancouver Island, all draw visitors to the area. The influx of tourists has made big changes in the town, including more traffic on the highway and longer lineups in the Co-op.

As old-timer Pete Hillier philosophically put it, “I guess we’ve always known it was coming…generally speaking it’s not all that bad—you at least get to meet some interesting people. And,” he reflected, “it’ll help the local businesses.”26