Chapter 4: The Fur Trade

Explorers, while seeking adventure and uncharted territory, were always on the lookout for riches. In 1778, when Captain Cook arrived at the village of

Yuquot, Nootka Sound, on the west coast of Vancouver Island, he traded for furs. Among those furs were sea otter pelts. Cook never knew he had acquired a treasure trove. By the time his expedition arrived in Canton (now Guangzhou), Cook had been killed in the Hawaiian Islands. But the crew soon discovered the Chinese would pay a goodly sum for the glossy pelts. Thus began the craze for “soft gold.” Members of the Cook expedition, keen to make more money, wanted to head right back to Nootka. News spread fast. In the words of author-historian Beth Hill, “It was like a coin dropped on the pavement of the world. All eyes swivelled to the North Pacific and many men considered how they could get a share of the vast wealth to be won by selling otter pelts to the Chinese.”1

The sea otter (scientific name Enhydra lutris as of 1922) has a thick lustrous coat ranging in colour from reddish to dark brown to black. The mammals have no blubber, and so they rely on their extremely dense fur to keep warm. The sea otter can grow up to one and a half metres long and weigh up to forty-five kilograms. The luxurious fur was a status symbol to wealthy Mandarins. Traders frequently exchanged the pelts for tea, silk and porcelain to take back to Europe.

Up to sixty ships ultimately went to Nootka, often trading over the side of the ships when Nuu-chah-nulth hunters pulled alongside in their canoes. In a Daily Colonist article published on September 21, 1969, West Coast historian George Nicholson estimated from traders’ journals that 225,000 pelts were taken between 1785 and 1810, for sale in China and on Boston and European markets.

Greed led to the near-extinction of the sea otter. Finally, in 1911, action was taken. Great Britain (for Canada), Japan, Russia and the US signed an international treaty prohibiting hunting of North Pacific sea otters and fur seals.

Overhunting of the sea otter affected nature’s fine balance. They were successfully reintroduced to the West Coast, again changing the ecosystem. Massive kelp forests began thriving, because sea urchins, once destroyers of the kelp, were being consumed in large numbers by the sea otters. (Sadly, kelp forests are struggling again, this time because of warming sea temperatures.) Although sea otter populations have rebounded, they are still considered an endangered species because of low numbers in some areas.

Sealing

Having decimated the sea otter population, traders turned their attention to the fur seal. The Nuu-chah-nulth used seals for food and clothing, and soon found seal pelts were a valuable trading commodity. In Ucluelet, Captain Charles Stuart ran a short-lived trading post. Captains William Spring and Peter Francis partnered in a longer-lasting, more lucrative enterprise.

The First Nations hunters paddled their dugouts thirty to fifty kilometres offshore, to the seals’ feeding grounds. They were highly skilled at this dangerous work. The season spanned from January to the end of June, encompassing some extremely rough weather.

In the 1860s, Spring and Francis started transporting hunters and their canoes from Ucluelet out to the sealing grounds. The nuučaan̓uł men hunted all day with spears and harpoons, then returned to the schooner to process the pelts. This method was intended to be more efficient, and safer for the hunters. The seals were skinned on board, and the furs preserved in salt. Fourteen schooners practised pelagic sealing by 1882, with captains vying to hire the best Indigenous hunters.2

Victoria thrived as a sealing trade base. In 1881, a live seal was on display in Victoria: “A fine specimen of a fur seal was brought up alive and may be seen at Levy’s restaurant.”3

The publications of the day teemed with sealing news. The Daily Colonist of April 22, 1885, reported West Coast Indigenous hunters were on strike, demanding an increase from three to five dollars per skin, with business owners saying they couldn’t afford it. In May of the same year, the average number of sealskins per ship was four hundred, although Captain McLean, in command of Spring’s schooner, the Favourite, had brought in eighteen hundred the previous year. By 1895, Victoria was considered the world sealing headquarters, with a fleet of sixty-five schooners. Roughly $500,000 came into port each year.4

In 1900, the Colonist reported that the Nuu-chah-nulth hunters, wanting a fair share of profits, asked sealers for seven dollars per skin. Storekeepers paid up to fourteen dollars per skin when they sold to them directly. By 1901, West Coast sealing schooners were having trouble hiring First Nations hunters owing to the lack of pay increases.

Then schooners started taking hunters all the way up to the Bering Sea, where four countries competed in the seal hunt. As with the sea otters, the seal population was decimated. Thankfully, they also gained protection when the 1911 international treaty was signed.

The Daily Colonist of June 1, 1913, under the headline “The Passing of Victoria’s Most Romantic Industry,” waxed eloquent over the end of pelagic sealing. The article described “a great fleet of aging vessels” anchored in Victoria Harbour as owners awaited compensation for loss of income.

Sealing continued along Vancouver Island’s west coast. Captain Charles Spring, son of Captain William Spring, commented on the use of firearms, saying he “had no doubt as to the superiority of guns over spears,” but admitted that several seals were wounded and not recovered. He also said Indigenous hunters were against the use of firearms as they frightened the seals away,5 later adding that “to a considerable extent, their idea proved correct.”6

In Ucluelet, Edwin Lee, proprietor of Lee’s General Store, traded with First Nations hunters for sealskins. In 1928, the Governor General of Canada, Lord Willingdon, and his wife visited Ucluelet on the inaugural voyage of the Princess Norah. Lord Willingdon was so enthralled by Lee’s description of preserving sealskins for shipment that he clambered into a bin full of them for a closer look.

As coastal sealing continued during the first half of the twentieth century, the seal population dwindled. After commercial sealing was banned in 1970, seal and sea lion populations eventually rose to a record high, raising concerns about negative effects on salmon stock recovery. The discussion continues.

Charles and Frances Barkley

Ucluelet Harbour opens into Barkley Sound, a body of water covering approximately 525 square kilometres. The sound is exposed to the tumultuous seas and rolling swells of the open Pacific.

Barkley Sound was originally given the Indigenous name of Nitinat Sound. In the early days, it was referred to as an archipelago, owing to its large number of islands. On a 1791 map based on Spanish exploration, the sound is labelled “Archipielago de Nitinat o Carrasco.” Ucluelet and the nearby area is shown as “Boca de Canaveral.” Ucluelet Inlet is not on the map.7

Captain Charles William Barkley named Barkley Sound after himself upon arriving in 1787 aboard the British trading vessel Imperial Eagle. (The sound was incorrectly labelled “Barclay Sound” on some early charts.) Captain Barkley was a commanding figure, but his young wife Frances captured more attention.

Charles had first set eyes upon seventeen-year-old Frances Hornby Trevor in Ostend, Belgium. After a whirlwind courtship and hasty marriage, they sailed aboard the Imperial Eagle on Friday, November 24, 1786, bound for the Northwest Coast of North America in search of soft gold. Frances Barkley kept a diary, providing gripping details about her travels, including wild weather, her husband’s illnesses and unwanted attention from crew members.

They arrived at Nootka in June 1787, likely with relief, “the day previously to making the land a dreadful storm from the south-east having been encountered.”8 Aboard the first trading ship of the season to arrive, they successfully acquired eight hundred luxurious sea otter pelts. The Nuu-chah-nulth were no doubt taken aback to see Frances, not only purported to be the first European woman on the Northwest Coast, but also with a flowing mane of red-gold hair. Her maid Winee was said to be the first Hawaiian to arrive on that coast.

Trade went well, but Captain Barkley decided to leave Nootka soon after two British ships arrived. Their captains were disgruntled because Barkley’s ship had taken so many pelts. They also quickly figured out the Imperial Eagle was bypassing the requisite British licensing system. Charles left hastily, but information about illegal trading would follow him to his destination.

Sailing south from Nootka, they came upon a large sound that Frances later noted was named Wickaninnish’s Sound, after a Chief of “great authority.”9 It is now called Clayoquot Sound, after the Tla-o-qui-aht Nation of that area.

Continuing southward, they reached the large body of water Charles named Barkley Sound. He also named the three main channels in the sound: Loudon Channel, Imperial Eagle Channel and Trevor Channel (after his wife’s maiden name). Barkley named Hornby Peak after his wife, and Cape Beale after the ship’s purser.

After leaving Barkley Sound, Barkley “rediscovered” Juan de Fuca Strait, and charted it. It had been “discovered” in 1592 by Juan de Fuca (a Greek man who was actually named Apostolos Valerianos, exploring on behalf of New Spain).10 Captain Cook had emphatically denied the existence of the strait.

Captain Barkley carried on down the coast into what is now Washington state, trading for more furs, until a tragic incident occurred. Six crew members, including the purser, disappeared while ashore seeking trading opportunities. The ship’s search party found nothing but bloodied clothing. Captain Barkley ended the trading venture then and there, named the site Destruction Island and Destruction River, and left for China.

From North America, the Imperial Eagle crossed the Pacific, arriving at Macao in December 1787. Word of their gains travelled afar. The Baltimore Gazette of August 20, 1790, reported them leaving Nootka “with a cargo of nearly 700 prime sea-otter skins and above 100 of an inferior quality…the price put on them was 30,000 dollars.”11 In Macao they sold their cargo for the projected 30,000 Spanish dollars, gleaning a substantial profit. At their next port, Calcutta, the tides suddenly turned on Charles Barkley’s career.

The two British ships encountered in Nootka had sent news to England about the Imperial Eagle’s unlicensed fur trade. When the East India Company threatened legal action, the backers of Barkley’s venture broke his contract. They sold the ship out from under him, and his possessions as well. Many of Captain Barkley’s belongings, including his charts and records of the voyage, fell into the hands of Captain John Meares. Meares later falsely claimed many of Barkley’s accomplishments as his own. Frances wrote: “Capt. Meares…with the greatest effrontery, published and claimed the merit of my husband’s discoveries…besides inventing lies of the most revolting nature tending to vilify the person he thus pilfered.”12 Others, including captains Haswell and Dixon, also accused Meares of lying and stealing. Chief Maquinna of the Mowachaht Nation played a key role in the fur trade, and called Captain Meares “Aita-aita Meares,” which means “the lying Meares.”13

Luckily for us, Frances wrote that and so much more. In her later years, she referenced her diary while writing a memoir called Reminiscences. And more luck ensued when author Beth Hill discovered the thin notebook of Reminiscences in the BC Archives and used it as a base for her fascinating 1978 book The Remarkable World of Frances Barkley.

Captain Charles Stuart

Captain Stuart arrived in Ucluelet early in 1860 and established his own trading post at a small bay called hac̓aaqis, near the mouth of Ucluelet Harbour. The site was adjacent to the present village of hitac̓u, and in typical colonial fashion of the time, became known as Stuart Bay. Stuart’s time in Ucluelet was brief and controversial.

Previously employed by the Hudson’s Bay Company, Stuart had been officer-in-charge of their trading post in Nanaimo. He also served there as local magistrate and was known to mete out harsh punishment. He was discharged from the HBC position in 1859 because of “chronic drunkenness.”14

When Stuart arrived in Ucluelet aboard the schooner Victoria Packett in early 1860, the news spread quickly. Eddy Banfield paddled twenty-four kilometres by canoe across the open waters of Barkley Sound to greet the new settler and introduce him to the local First Nations people. Banfield was then Indian agent at Bamfield, and Captain Stuart was to be the Indian agent at “Euculet.”15

Stuart soon gained notoriety on the coast. In December 1860, the Peruvian brigantine Florencia went on the rocks approximately eight kilometres west of Amphitrite Point, and Stuart quickly tried to profit from the catastrophe.

He rushed to the site, pressuring the crew to sell the vessel at once. As the only stranger there, his bid of $100 was accepted by the first mate, despite protests from the rest of the crew. Stuart thought he had himself a bargain, but others begged to differ. Insurance underwriter Captain Edward Hammond King soon arrived from Victoria and declared the sale null and void. King then set sail home on board the schooner Saucy Lass, with his brother and several friends. Also aboard was none other than Captain Charles Stuart.

The ship cruised through Barkley Sound, where the passengers enjoyed fishing and hunting. Tragedy struck as King and a friend hauled up their canoe on a nearby island to hunt mink. King accidentally shot himself, with a whole charge of buckshot passing through his torso into his left shoulder and nearly tearing off his arm. Back on the ship, King told Stuart, “Oh, I’ve only blown my arm off.”

After three days aboard the Saucy Lass, twenty-nine-year-old King succumbed to his injuries. In a letter, Banfield questioned why King “remained three days in the miserable little vessel.”16 Captain Stuart stated at the inquest that a gale had prevented them from transporting King by canoe to Victoria for medical aid.

Several years later, Captain Charles Stuart also met his demise. By then, he had a ranch on the Qualicum River but still went to sea. A notice in the Daily Colonist stated, “This company, Sangster island Copper Co. has chartered the sloop Red Rover to convey miners and material to the promising mine recently discovered by Capt. Stuart.”17

Stuart fell ill with bronchitis off Sangster Island in December 1863, and died there aboard the Red Rover at the age of forty-six. He is buried in the old cemetery in Nanaimo, BC. Despite what could be called a chequered career, Stuart had five places named for him: Stuart Bay in Ucluelet Harbour, Stuart Anchorage, Stuart Bight, Stuart Channel and Stuart Point.

Captain William Spring

William Spring was born in October 1831 in Libau, Latvia, to a Russian mother and a Scottish father. Libau, as the only ice-free port on the Baltic, was one of Russia’s busiest ports. William’s father worked there as a civil engineer for a railway company. Shortly after William’s birth, the family moved to Scotland.

William left home at sixteen, choosing a life at sea. He arrived in Victoria, BC, from Hawaii via San Francisco in 1853, aboard the schooner Honolulu Packet.

The enterprising young William sold supplies to gold-rush enthusiasts in Bella Coola, then ran a cooperage in Sooke, BC. Next, he acquired a fleet of sailing ships with partner Hugh McKay, trading from Washington state up to Alaska.

In 1864, Spring joined forces with Peter Francis, and together they established a trading station at Port San Juan on the west coast of Vancouver Island. More trading posts followed, including at Copper Island (Tzartus), Pachena River, Dodger Cove and Ucluelet.

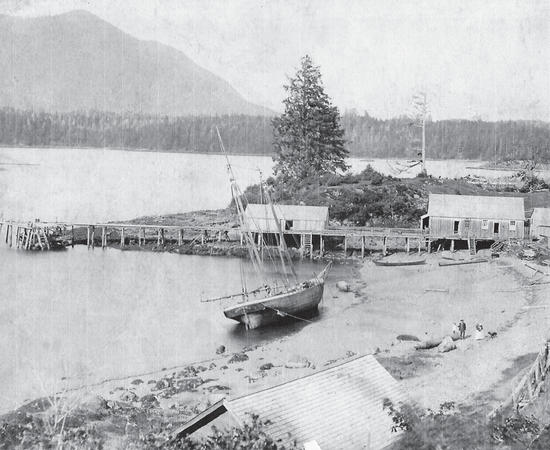

The Ucluelet trading post was on the west side of the harbour mouth at Spring Cove, strategically located with open ocean access. The Indigenous name for the site, Hinapiis, means “land between two pieces of water.” It is said Captain Spring acquired it from the Ucluelet First Nation in trade for a barrel of molasses.18

Captains Spring and Francis included Hugh McKay in their enterprise, pursuing the lucrative seal trade under the name Wm. Spring and Company. Their fleet of sailing ships were in use year-round, sealing during the summer, then transporting freight and trading the rest of the year. The partners also cured salmon for the growing trade with Hawaii.

The Favourite

One of Spring’s best-known ships was an eighty-one-ton schooner of French design. The “stoutly-built” ship with an elliptical stern was built by Smith Burr, one of BC’s first boatbuilders. She was then named the Favourite and launched in Sooke in 1868. Spring put her to work as a trading vessel. She took fish, shingles, liquor and iron to Hawaii, returning with sugar, molasses and fruit. She took coal and lumber to Mexico, returning to Victoria with California redwood.

In 1873, Spring decided to try the Favourite for sealing. She became “one of the longest-serving and most successful in the sealing fleet.”19 Local newspapers publicized her successes, including the time Captain Spring brought almost two thousand sealskins into Victoria.20

William died in March of 1884 at the age of fifty-three. Cause of death was described in his obituary as a disease causing paralysis that started with numbness in his feet and spread throughout his body. Charles left behind his wife, Susan Ciama Skiapizet, daughter of a Salish Chief. He was also survived by five of their seven children. His son Charles took over the sealing business, partnering with Peter Francis and continuing with the family business for many years. In 1912, he suggested the cove in Ucluelet be named Spring Cove, after his father.21

Captain Peter Francis

Francis Island lies at the southwest corner of the entrance to Ucluelet Harbour, close to Spring Cove. The island is named for early trader Captain Peter Francis, long-time partner of Captain William Spring. Originally named Round Island, it was renamed in 1912 at the suggestion of Charles Spring.

There are conflicting records regarding Captain Peter Francis’s place and date of birth. One record states he was born in 1828 in the small French fishing village of Plouézec, and christened Pierre Marie Perron. The 1881 Canadian census shows him born in Jersey in the Channel Islands in 1828. His death record says he was born in the Bailiwick of Jersey in 1826.

He arrived on Vancouver Island around 1850, and by 1855 was going by the name of Peter Francis, although many First Nations people called him “Pike.”

Francis was a Roman Catholic with ties to the coastal Catholic missions. When he started trading in the mid-1850s, it was mainly for dogfish, which was used for oil in sawmill machinery. Dogfish oil was also exported to England. The First Nations traded the oil for molasses, blankets, fabric, beads and other items. Francis spoke the languages of the West Coast tribes and reportedly had mainly positive trading interactions.

A letter dated July 17, 1855, to James Douglas, governor of Vancouver Island, stated Captain Francis had been trading on the west coast of the island for the previous twelve months, adding that “Mr. Francis has had ample means of ascertaining, the tribes from Port San Juan to Clayoquout [sic] accurately.”22 Francis describes “You cluel yet” as “a pretty little cove, when entered a mere reef of rocks outside, with a little piece of clear land about 2 miles from the village. We have not ascertained anything in the shape of minerals nor anything that would warrant Colonization.”

He goes on to say: “You cluel yet is situated on the Head land which forms the Northern extremity of ‘Nettinet Sound’ the total population is about 350. We have judged about 100 warriors. Our impressions from the experience of frequent visits, is that they are not too courteous.”23

Although Francis had stores up and down the coast, his main residence and trading post were in Ucluelet, in partnership with William Spring. The two men initially competed in the trading of oil and furs, but after joining forces in 1864, they remained partners for twenty years.

By 1871, there was great demand for seal fur to make the fashionable hats so popular in large European and American cities. Francis and Spring added three more schooners to their fleet. In the late 1870s, a few schooners were converted to steam power, but Francis and Spring considered their business as thriving under sail. By 1883, sealing was vastly changed. As steam-driven ships went sealing and guns replaced harpoons, seal populations were decimated.

Throughout his years on the West Coast, Captain Francis considered Ucluelet his home. Spring dealt with most of the business at their Victoria headquarters, but Francis made occasional trips there as well.

On one of these trips, he met Cecelia Billings, whose father was a British cooper and mother a member of the Klallam First Nation. Forty-six-year-old Peter married sixteen-year-old Cecelia in Victoria’s St. Andrew’s Cathedral, in August 1874. Francis brought his new bride home to Ucluelet. Also aboard the Surprise were the Catholic missionaries Father Augustin Joseph Brabant and Bishop Charles Seghers. Captain Francis celebrated the marriage by drinking heavily, inspiring a crew member to hide all the liquor. Brabant wrote that it was great fun to watch as the skipper searched the vessel for the missing alcohol, and then accused the clerics of concealing it.

En route to Ucluelet, as the ship attempted a stop at Spring’s store near Pachena, Francis “was far from being sober” and the ship struck a sandbar at full speed. Father Brabant wrote: “The Channel had shifted, or rather our Captain was out of his reckonings through whiskey!”24 Local storekeeper Neils Moos came aboard and got the Surprise off the sandbar. The ship reached Ucluelet without further mishaps. One wonders what sixteen-year-old Cecelia thought of her introduction to marriage.

Once settled in Ucluelet, Cecelia ran the trading post when her husband was away. Their four children were born in Ucluelet and baptized in the Roman Catholic faith.

Captain Francis fell from the mast of one of his ships while showing a sailor how to properly set sails. He was taken to St. Joseph’s Hospital in Victoria, where, two months later, on April 30, 1885, he succumbed to his injuries, which had been further complicated by heart disease. He was fifty-seven years of age.

Cecelia remarried eight months later, after moving to Seattle with their three surviving children. When second husband James Mitchell passed away, she married George Roberts. Cecelia outlived all three husbands, passing away in 1928 at the age of seventy.