Chapter 21: Fun and Recreation

Owing in no small part to their isolation, the residents of Ucluelet and area formed a close-knit community. They worked hard, and they created their own opportunities for fun and recreation.

Locals gathered for picnics at Wreck Bay and Long Beach or boated over to the Shelter Islands for get-togethers at August Jansen’s beach. Fishing, in both the ocean and local streams, was a common pastime, as was hiking, clam digging, raking in crab and, for those who had cars, sedate drives or speedy races on Long Beach’s hard-packed sand.

Spring Cove was a popular gathering place. A Victoria newspaper described the May 24 celebration in 1911: “Empire Day Sports Prove Success—Large Number Attend Celebration at Ucluelet—Over $400 in Prizes.” Races, on both water and land, “were keenly contested,”1 and included a cigarette lighting race and a needle threading race. A reported forty dollars in prize money was awarded, suggesting the “$400” in the newspaper headline was either a typo or fake news. The article concluded: “The weather was ideal and everyone went to their homes saying that they had witnessed the best celebration ever held in this thrifty and rapidly advancing settlement.”2

My Uncle Art was on a winning streak on Empire Day, 1926, coming in first in the small-canoe-no-paddle race, and partnering with George Hillier to beat George’s brothers Pete and Bert in the upset-canoe race. There was land-based pillow jousting and a canoe jousting match, in which Cecil Mack and Victor Tom were victorious.

The sports extravaganza was followed by dancing at the schoolhouse, with “a special orchestra supplying the music.”3

The Japanese Canadians shared their heritage at these community gatherings. An article in the July 5, 1936, edition of the Daily Colonist describes local girls in brilliant kimonos performing traditional dances at the yearly Dominion Day celebration. Their names are listed as Nellie Morishita, Mary Terashita, S. Tamai, Kay Ota, S. Shimizu and Hanako Mori. The same article mentions the Tofino YMCA as guests of the Ucluelet Taiyo Club, where those in charge of sports events at Spring Cove were Shigeru Nitsui, K. Sathai, K. Atodai, N. Yoshihana, Bert Hillier, Tom Tugwell, Stan Littleton and W. Fraser. Tommy Kimoto, visiting from Clayoquot Island, won every race he entered that day and was nicknamed “Battler.” During the camaraderie of that Dominion Day, war and internment were several years in the future. When they ended, Tommy Kimoto would settle in Spring Cove, unable to reclaim his original home near Tofino.

The school at the bottom of Main Street was a community hub, often used for parties, including Christmas celebrations.

A Victoria newspaper described a Ucluelet Christmas party in the school hall, where “the large Christmas tree, bearing gifts for the children, was the main attraction for the younger folk. After the distribution of presents the remainder of the evening was spent in dancing.”4 That week, the Ucluelet Hotel was “the scene of a jolly dance” where “the music was ably supplied by Mr. George Fraser.”5 The same newspaper, which back then tracked comings and goings up and down the coast, mentioned that my father K. Baird had returned to Ucluelet after a visit to Port Renfrew. I wonder if he was home in time to “cut a rug” at the Ucluelet Hotel.

Themed dances during the Depression included a “hard times dance” to see in the new year of 1932, when Herbert Hillier and Ruth Tugwell led a “grand march” through the community hall, with the crowd “exhibiting many patches and worn-out shoes.”6

Christmas meant family time, when the fishermen stayed home to avoid winter storms. It often snowed in December and January, and the children would slide down Main Street hill on new Christmas sleds. Those without sleds improvised, sometimes on ladders.

Dennis Craig recalled the festive partying of Christmas in the 1950s, when people gathered in groups and visited house to house. Residents set up goodies, alcohol and cigarettes on tables. Doors were left unlocked, and if occupants were also out partying, the revellers would go in and make themselves at home, then carry on to the next place. Teenage Dennis was “in training, so allowed to come along.”7

The Maddens had a large home next to their store, and often hosted parties. The kids were all sent upstairs, and observed what was going on below through a grate. The Maddens’ budgie had a cage with an open door and flew freely through the house. At these parties, he liked to sample the beverages and sometimes had to be tucked back into his cage after over-imbibing.

Children made their own fun. For her sixth Christmas, Margaret Thompson got a carpenter’s set, and from then on spent “a lot of time sawing things up.”8 She and cousin Molly Mead-Miller built forts and cut down trees; Molly liked to be in the top of the tree, riding it down as it fell. Building forts was a popular pastime, something I also did while growing up, as did my daughters after me. “That’s an era we’ll never ever see the likes of again,” Margaret said.9

The Mead-Millers had an ice cream machine, and Margaret recalled rowing across the bay to the cannery at Port Albion with her siblings and cousins to get ice for the ice cream. When they returned, they took turns cranking the handle on the ice cream maker. Pacific canned milk was the main ingredient, as fresh milk was hard to come by back then.

There were wild cows around town, left behind by departing pre-emptionists. Local kids chased them, often at night. Margaret recalled that during the pursuit the cows sometimes turned and chased them, she and her cousins running full-tilt to escape. Terry Smith said, “The poor things would finally get so annoyed with us they’d swim across the bay to Port Albion.”10 Sometimes the kids rode the cows. He also recalled Frank Everett’s sheep running around the grassy fields adjacent to a barn which stood on the site of the present-day police station.

One spring day, a horse named Mabel arrived in Ucluelet aboard the Princess Maquinna. Mabel was lifted off the ship in a sling, and put to work at Tom MacDonald’s sawmill, dragging logs from the woods to the mill. Sometimes Mabel took a break and walked the ten kilometres into town, where she followed a regular route to all the homes where people saved their vegetable peelings and the occasional apple for her. Part of her routine included sticking her head through a window at the barbershop to check things out. The local kids rode Mabel around town, a change from riding cows. Mabel had a mind of her own and would suddenly stop and refuse to budge until she was good and ready.

Kids spent hours fishing off the docks or rowing around the harbour; some spent more time on water than on land. Dennis Craig recalled that when Jimmy McKay came over from Stuart Bay in his dugout to shop, he would let the kids borrow it. Dennis and friends also had access to a few other rowboats. During the herring reduction plant run, the cormorants were so full that they couldn’t fly, and the boys would take them for a boat ride around the bay and then put them back to float in the water. Sea lions also got fat and lazy from snacking on leftovers from the plant. “You could poke them with a stick, and they wouldn’t move.”11

As a kid, Roger Gudbranson hunted ducks up the head of the harbour before school in the morning. He also went farther afield in his refurbished, once-abandoned boat, motoring up to Wreck Bay, with no bailing bucket and no life jacket. Terry Smith recalled that the kids were warned not to go fishing under the Standard Oil dock, and when his mom was looking for them, she knew that was exactly where they’d be.

Going to the beach was a popular activity. In the early days, Little Beach was considered “out of town.” The kids hiked down a trail and swam all summer at Little Beach. Another favourite pastime was hiking the boardwalk to the lighthouse, picking huckleberries en route, and then going rock scrabbling. There was no parental supervision, just a reminder to be home in time for supper.

Margaret Thompson remembered riding her bike on the boardwalk to Salisbury’s Tea Room at Spring Cove, and enjoying a twenty-five-cent piece of pie with a ten-cent cup of tea. She said it felt like being in a different community, as it was so far away.

Margaret also recalled family time gathered around the radio. There was great radio reception back then, with no interference because there was no electricity—hydro came in and ruined the radio reception. Roger Gudbranson enjoyed listening to The Lone Ranger on the radio.

A marine radio worker who lived in the Lodge brought the first TV to town. He put a huge aerial on the roof and had a small octagonal TV in his room. Kids would peek in through his doorway to see it. Later, a small TV was set up in the café downstairs. It frequently picked up PWA agent Helen Craig’s voice during her radio interactions with coastal pilots.

Ucluelet and Tofino teens often got together to socialize. Frank and Lavern Hillier recalled that in the ’50s, they would go to Tofino every second weekend, with the Tofino teens coming to Ucluelet on alternate weekends, as otherwise “there weren’t enough of them to have a party in either town.”12 There were house parties or beach parties at Long Beach or Chesterman Beach, with “anyone who was allowed out.” Frank said Chesterman was the best because someone had put a chain across the entrance to the beach. The teens separated the links, went through and then reattached them, and nobody knew they were there. (Other than the policeman at the time, Harry Bonner, who always knew where they were but never hassled them as long as they behaved reasonably. They all liked and respected Harry and were sorry to see him go when he was transferred out.) Before the road, when the solitary police officer parked his car behind Madden’s General Store, the local teens knew he had left to escort a prisoner to the city by float plane. Then it was “party time.”

Vehicles were brought in by boat, and the teens drove between Ucluelet and Tofino, and the length of Long Beach. Malcolm Mead-Miller had a 1937 Plymouth sedan. When the fuel pump quit, he tied a gas can onto the roof for gravity feed. When the police vetoed that, Malcolm tied a one-gallon gas can inside the vehicle above his head.

Driving 101

I did some driving at the seaplane base and on Long Beach, when I was fifteen. Turning sixteen meant I could get my driver’s licence! First, I needed some experience driving on actual roads, so Dad took me out in the family’s ’63 maroon-and-white Chevy Impala. Dad was a man of few words, but I do recall him sighing, then saying, “You don’t have to brake going uphill.” Each time we got home from a lesson, Dad went straight to the kitchen and poured himself a shot of whisky.

Soon after my sixteenth birthday, I had my driving test, which consisted of driving around the block. (There were no traffic lights or stop signs back then, and parallel parking, luckily, was not a requirement.) I got a “restricted licence” meaning I could drive only as far as the Taylor River bridge (actually a fair distance out Highway 4). At age nineteen I got my “out of town” licence, after my then boyfriend, now husband, taught me to drive in Victoria. During the first lesson on Douglas Street, he patiently informed me, “You just drove through two red lights.” I was so taken aback I made a quick right-hand turn—across the curb.

Vi Mundy told me her husband Bob drove far afield with his restricted licence. One time, he got pulled over by a policeman in Montana, who was so intrigued by Bob’s unique restricted driver’s licence that he let him off without a speeding ticket.

Recreational Clubs and Facilities

The Ucluelet Athletic Club (UAC) was formed by locals to promote athletic activities. Bylaws of the club were registered under the BC Societies Act in October 1932. The group created Ucluelet’s first sports field on Mr. Lyche’s property (later Littleton’s property), and also built a badminton court. The group formed a football team, with Pete Hillier and Ken Miller as first captains. The records note the need to order lime for the field, and also a football. The club members organized sports days.

They also envisioned indoor activities and set their sights on a building. George Fraser, with his characteristic generosity, donated a tract of land, which the members cleared by hand. Then they started construction, using wood salvaged from local beaches after a deckload of lumber washed off a freighter in heavy seas. Pete Hillier recalled helping build the hall in the early 1930s, “when there was no work and the fishermen were on strike…We had all this time on our hands and we were getting restless.”13

The original building was to be nine by five by three metres, but as enthusiasm grew, so did the structure’s dimensions. In 1934, dances still took place in the school, but plans to enlarge the UAC Hall were well under way. In 1937, the hall was lengthened by ten metres.

In 1938, a man was hired to build outhouses, a turkey raffle was organized, and it was noted that they needed to purchase cheese, crackers, soft drinks and cigarettes for their upcoming annual general meeting. The UAC members were a busy lot who liked to make the most of good weather; the AGM of 1942 was to be held on “the first stormy night” after April 28.

The UAC Hall soon became a multi-purpose building. True to the club’s “athletic” name, it hosted badminton, basketball and floor hockey. In 1940, the group bought roller skates; the floor took a beating (which perhaps contributed to the need for a new floor in 1957). Volunteers of all ages pitched in for the upkeep of the hall. Margaret Thompson recalled painting stripes on the floor for badminton in her teen years.

The club hosted festive parties and dances. In 1939, admission for dances was thirty-five cents for non-members—members got a ten-cent discount. Live music was supplied for many years by George Fraser, Ken and Sheila Mead-Miller and Bud Thompson. They were later joined by George and Ruby Gudbranson and Jimmy Waters.

The hall housed various children’s groups, including kindergarten and dance classes. It also served as venue for movies, talent shows, fashion shows, potluck dinners and many a wedding reception, mine and my daughter’s included. The annual Strawberry Tea and Holly Tea always drew a full house. Santa dropped by for the annual Children’s Christmas Party, his sack brimming with gifts for every child.

The Sea Scouts met in the UAC Hall but spent a lot of time out on the water under the leadership of George Sherman, local customs officer. The group had two former CPR lifeboats named the Francis Isle and the Lyche Isle. The white, green-trimmed boats were clinker-built, and had six oars, three to a side, and a rudder. The Scouts rowed around the bay and camped on Francis Island or at Mercantile Creek, where the UAC had leased property for a campsite. Sometimes they rowed out to the mouth of Maggie River. Their parents boated out on a Sunday to visit them at their campsite. Over the years there were also Cubs, Brownies (a group now called Embers), Guides, Rangers and other organized groups, all run by volunteers.

On June 1, 1992, because of dwindling membership, the UAC passed ownership of the hall and property to the Village of Ucluelet. “Times have changed,” Roger Gudbranson said in a Westerly News article. “We took over where our parents left off, but now there’s no group to take over.” He fondly recounted good memories, adding: “There is a closeness, like a family, among the members.”14

On September 1, 1992, the Ucluelet Lions Club, the local branch of an international service organization, took over the operation and maintenance of the UAC Hall under a lease agreement with the Village. They set to work with renovations and upgrades, and held their meetings and events in the hall, also offering its use to other groups. The Lions Club raised funds to provide community Christmas hampers, and built and maintained a playground across from Whispering Pines trailer park. They also gifted seniors with firewood, cutting up logs from logger sports competitions. One time, they cut and split the legs of the old Millstream water tower.

Ucluelet’s Army Navy and Air Force Unit 293 was an active veterans club for many years, and community members gathered there for parties, pool tournaments and shuffleboard. On Friday nights, Serge Noel or Dave Taron’s disc-jockeying skills ensured a packed dance floor. Membership gradually dropped, and a major downswing came in 2015, when the BCANAF Head Command considered shutting the Ucluelet unit down owing to lack of revenue. The unit was revitalized through the work of Bronwyn Kelleher, John McDiarmid, Dave Brown, Leslie and Andy Horne and others. Music and comedy shows, dances, bingo, game nights, artisan markets and more all help keep the club active and dynamic, taking it from the red into the black. Respect for the early veterans is shown through historical exhibits and yearly Remembrance Day ceremonies.

The Ucluelet Recreation Commission, like the UAC, was a group of volunteers formed to provide recreational activities. Most of these took place in the Ucluelet Recreation Hall. The hall was built in the early 1940s as a recreation facility for the military personnel at the seaplane base. For many years, it was the main community hall for Ucluelet. It was used for dance classes, gymnastics, roller skating, floor hockey and basketball. Movies were shown there. It was also a venue for talent shows, with an assortment of us “young ’uns” performing dance routines or attempting a tolerable musical offering.

I recall Highland dancing onstage, as well as playing accordion duets with Susanne Smith (now Bisaro). One year, Joan Reite was the hands-down winner with her melodic solo of “Johnny Angel.”

Graduation ceremonies were held at the Rec Hall for many years. I remember standing on that stage decked out in a satin dress, sparkly shoes and back-combed hairdo as I delivered my valedictorian speech for high school grad in 1969. Graduation then, as now, was a community event.

Over the years, that great barn of a building called the Rec Hall gradually deteriorated. There has been intermittent restoration work done through grant monies and Village funding, but upkeep of this aging facility is a constant concern. The Rec Hall (despite irreverent references to the “Wreck Hall”) is still used for popular activities like roller skating.

Swimming

Early swimming classes happened at Little Beach, where Carl Binns taught swimming so many years before. I clearly remember the freezing water, the toe-nibbling crabs and the slimy kelp wrapping around my limbs as I attempted the jellyfish float. The bonus of lessons at Little Beach was that I floated better in salt water.

Then, under the umbrella of the Ucluelet Recreation Commission, swimming lessons relocated to Kennedy Lake. At the start of every swim season, machetes swung, as my father and several other MacMillan and Bloedel employees cut back alder branches along the road to Swim Beach, creating access through a shaded tunnel. We were usually transported to and from swim class in M&B crummies. The local public health nurse, Myrt Saxton, was an organizer of and swimming instructor for the Ucluelet Swim Club. She was up to the task, having qualified for the Olympics as a teenager (although unable to attend for financial reasons).

An early swim instructor was a young Australian man named Dave Lyall, who had the option to work in a larger centre but was drawn by the novelty of the isolated west coast. In the late 1950s the Recreation Commission hired Walter Lhotzky as recreation director. Walter taught all levels of swimming and organized regattas at Kennedy Lake. Proficient at many sports, he also taught gymnastics at the Rec Hall.

Car-less teenagers wanting to spend the day at Kennedy Lake Swim Beach knew to stand outside the Lodge early in the morning to catch a ride on an M&B crummy. They would get out at Kennedy Lake Camp, take another crummy along East Main, and be dropped off at the boardwalk with instructions to be there at 4 p.m. if they wanted a ride back.15

Bowling

The bowling alley was built by Henry Bonetti on Peninsula Road, at the entrance to the village. He named the facility Evon Lanes after his daughter Yvonne. In my early teens, I set pins at the bowling alley to earn pocket money. My brothers liked to bowl the lane I was working and really send those pins flying. I had to be quick on my feet.

When Guy Taron bought the business, he renamed the bowling alley Ukee Lanes. Guy’s son and daughter-in-law, Robert and Geraldine Taron, in partnership with their friends Dennis and Dianne St. Jacques, purchased the business and renamed it Smiley’s. The St. Jacqueses bought the Tarons out after a year and went on to have twenty-four-hour openings for the business—a Ucluelet first! The Van family were the next owners. Bowling went full-tilt from the days of Henry Bonetti to the Vans, with teams of all ages competing in tournaments. When Kent Furey and Amie Shimizu bought the business, they renamed it Howler’s and eventually did away with the bowling lanes but maintained a popular family restaurant.

Curling

A group of volunteers formed a curling club and put in three sheets of ice in one of the old hangars at the airport near Long Beach. Tofino families were also involved, making for “good camaraderie between both towns.”16 The ice was sometimes made available for skating, which was especially appreciated around Christmas. In the 1950s, the Curling Club raised funds by sponsoring “fly-ins” to the airport and Long Beach. Small planes arrived from all over North America. Curling Club members catered the event, in 1959 cooking up eighteen hundred crab on propane stoves on the beach to feed the hordes.

With the Curling Club long gone, the passion for ice remains. The West Coast Multiplex Society formed in the late 1990s and continues to pursue its dream of an NHL-sized ice rink and a swimming pool centrally located at the airport. At the time of writing this book, the volunteers remain committed and have added a surf centre to their proposal.

Surfing

Early Ucluelet surfers included Paddy Littleton, Mike Mead-Miller, Terry Smith, Dave Freemantle and high school teachers Dave McIntosh and Dave Conway. Terry was inspired by seeing the movie Endless Summer at the high school gym. Dave and Bev Conway (née Nakagawa) lived at Wreck Bay and the group often surfed there; on one Christmas Day, they surfed such big seas and massive curlers that they later questioned why they had been out there. Since those early days, Ucluelet has experienced a huge upsurge in surfing, with lessons for all ages and a lively scene.

Golfing

The Long Beach Golf Course opened in 1985, bounded by the airport on one side and a whole lot of bush on the other. Long-time Ucluelet residents Al and Rose Davison had a vision and, with other golf fans, made it happen. Al knew many locals willing to help, and Rose was an expert at finding grants and affordable loans. When Al walked the course one day with the designer, the fellow stared at the “controversial final hole,” with its massive tree smack in the middle of the fairway.17 Turning to Al, he said, “You’ll want to drive a big iron stake in the ground right here.”18 Al asked why, and was told, “Because after dealing with that tree, a lot of golfers will want to wrap their clubs around the stake you conveniently put there for them.”19

Despite that tree, the nine-hole course has been consistently popular and appreciated for its natural setting. Sometimes golfers must make way for bears. And when the members built a driving range and strung nets to keep the balls out of the forest, more bears arrived. The nets, donated by local fishermen, reeked of fish, luring the bears in to rip the nets down. Keith “Gibby” Gibson managed the golf course for years, describing it as “a hidden gem,” with “no tee time, no stress—just the great outdoors, West Coast style.”20

Biking

Cyclists can now pedal from Ucluelet to Tofino on a designated bike path. Ucluelet decided in 1996 to put a bike path in while constructing a line to supply Ucluelet with water from an aquifer near the junction. The Village paved the path as a bonus for the community and visitors. Council also purchased a truckload of two-metre trees to provide a noise buffe r for homes next to the path. In 2022 came the grand opening of the ʔapsčiik t̓ašii bike path (pronounced “ups-cheek ta-shee”) through Pacific Rim National Park, which connects to Tofino’s bike path. In 2023, a one-kilometre section through the Regional District completed the town-to-town link .

In 2020, the Ucluelet First Nation and the Ucluelet Mountain Bike Association collaborated on an exciting project. Nine trails on č̓umaat̓a (Mount Ozzard) offer mountain-biking options and an opportunity to connect with the land and reflect on its Indigenous significance.

Ukee Days

In the earlier times, Empire Day was a big cause for community celebration.21 Parades featured creatively designed floats, with the flower-decorated floats of the Japanese Canadian residents always a favourite. A chosen queen and several princesses reigned over the festivities. In 1974, three young members of the volunteer-run Recreation Commission, Robert Taron, John Winpenny and John Fitzpatrick, envisioned a community celebration incorporating logger sports, a fishing derby and west coast festivities: Ukee Days was born. A jam-packed three days of fun-filled activities, it continues to draw huge crowds and bring scattered Uclutians back home.

The Ukee Days weekend is supported by local sponsors, both businesses and individuals. It is organized by Ucluelet Parks and Recreation, but many people offer their time and energy to make it work. Volunteerism is key. Proceeds from Ukee Days go towards covering costs, and for years profits went to funds for a new community centre.

With Ucluelet’s population increasing and the historic UAC Hall and Rec Hall aging, it was time for a new multi-purpose centre. This came to fruition at the corner of Marine Drive and Matterson Drive, across the road from Big Beach. Dianne St. Jacques, the mayor at the time, dug the first hole for the official groundbreaking on October 3, 2008. The Ucluelet Community Centre officially opened in April 2010.

The well-used facility includes activity rooms, an arts-and-crafts room, a dance and fitness studio, large main hall, kitchen and the George Fraser Room, with theatre seating. Attached to the community centre are a public library, the offices of the West Coast Community Resources Society, and a daycare centre.

Hunting for Glass Balls

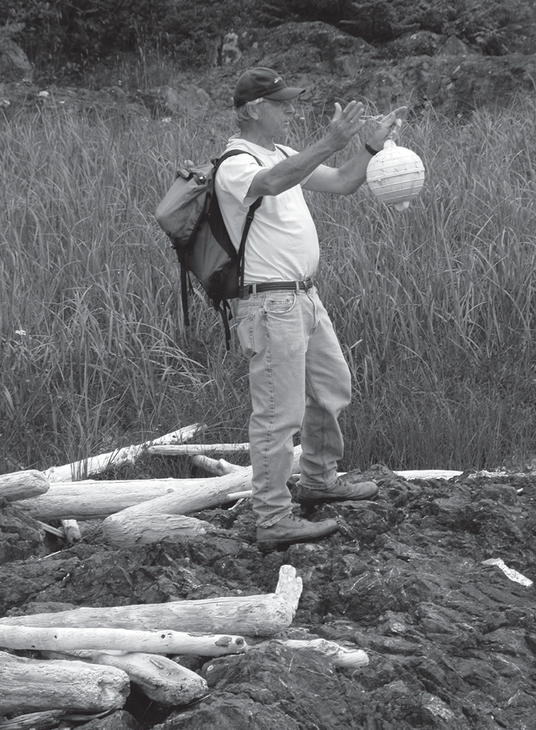

Beachcombing, a recreational pursuit for some and a passion for others, involves being ever-vigilant for the ultimate prize: a glass ball.

The glass balls found on the West Coast are Japanese fishing floats. When they break free from nets, some of them float across the Pacific to our waiting shores. Their journey can take ten years or more. Glass balls were used in many countries in Europe, after Norway first developed them in the mid-1800s. Japan began using them around 1910. Their first glass balls were hand-blown, some from recycled sake bottles. More recent glass balls, made in a wooden mould, have a ring around the middle. The most common colours are shades of green and blue. Rarely, purple ones are found, and sometimes even orange. Usually, spheres are found, ranging from tennis-ball to basketball size. Rolling-pin shapes are less common.

My cousin Lois Moraes lived at Long Beach before the national park was created, and frequently hiked the beach. One day, she was at Combers, a long way from her home up above the Wick, when she spotted glass balls. It was quite a haul. There were three midsized ones, six more the size of basketballs, and some other small ones. Lois hid them above the high tide line, then spent the better part of a day carrying them in shifts to her home. She then hurried down to share the news with Phyllis Martin, who was staying at Long Beach Bungalows. From the window, Lois spotted a large glass ball in the surf, ran and jumped across floating logs to grab it. “It wasn’t the smartest thing to do,” she told me. “I could have broken a leg, or worse!” But such is the thrill of the chase.

Jan Smith knows the extremes involved in the chase. While commercial fishing with her husband, Mike, aboard the Blue Eagle, she spotted a huge glass ball, fully netted and barnacle-laden. The fishing gear was out as Jan hung over the side of the boat, Mike gripping her by her gumboots. The treasure slipped from her rubber-gloved hands. Mike took his turn over the side, with Jan holding on to his heels. They would not be going home without that glass ball—they got it, and it’s a beauty!

The greatest glass-ball find award, at least off the Wild Pacific Trail, goes to Laura Griffith-Cochrane, curator of the Ucluelet Aquarium. While running the trail, she spotted something large afloat in the distance. Laura asked “Oyster Jim” Martin, who was working on trail maintenance, if he had binoculars with him. He didn’t. Laura was fairly sure it was a glass ball, so she dove off the rocks and swam for it. What a prize! The glass ball was huge, encased in netting and harbouring live pelagic barnacles. Laura displayed her find in a large tank at the aquarium.

Although glass balls are no longer used to the extent they once were, there are no doubt thousands of them still out there, floating in the Pacific. When the winds and the currents are right, some will complete that amazing journey to end up on our shores.