Chapter 23: Coastal Creativity

The art of the

nuučaan̓uł (Nuu-chah-nulth) is rich, complex and diverse.

The arrival of the uninvited, with their banning of the Potlatch and confiscation of Nuu-chah-nulth cultural materials, had a devastating effect. The newcomers viewed the items as commodities, oblivious to their inherent value and meaning. Tlehpik Hjalmer Wenstob, a Tla-o-qui-aht artist with strong Ucluelet community ties, writes: “Art. Art? There isn’t a Nuu-chah-nulth word for art: the act of art came about from moving the mask from the face and dance floor, onto the wall and behind glass. With historic actions of theft and purchase, objects of culture have now transformed into objects of art.”1 Hjalmer goes on to state that although masks are traditionally things of beauty, it is in ceremony and dance that they come to life.

Renowned Kwakwaka’wakw artist Beau Dick writes: “Our whole culture has been shattered. It’s up to the artists now to pick up the pieces and try and put them together, back where they belong.”2

Contemporary Indigenous artists create both traditional and innovative works. Repatriation of taken treasures has begun, but many more items have not yet returned to their rightful homes.

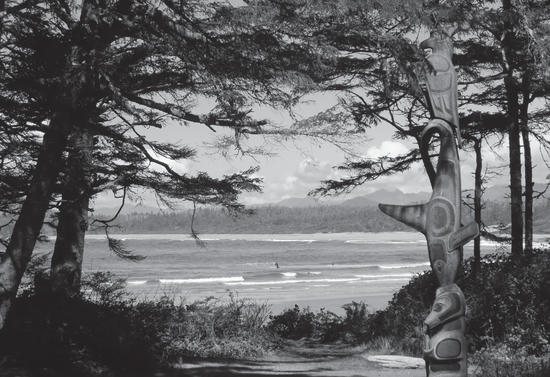

nuučaan̓uł art has been described as “an illustration of their spirit world.”3 Carved and painted poles depict origin stories, family crests, lineage and the marking of occasions. Clans are named after different animals, often depicted in artwork. Clan members are said to share the particular animal traits of their clan’s namesake. The pole designs are richly symbolic, expressing interconnecting relationships with animals, the environment and the spirit world.

A beautiful pole carved by Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ artist James “Hudson” Cootes stands at Kwisitis, on the trail past the Visitor Centre. Jim Cootes was a resident of Hitacu, and came from a family of talented artists, including older brothers Art and Ellery. “Carving is a gift from our creator,” Art said. “Some of us get the gift naturally…others have to work at it.”4

A powerful eagle pole created by Clifford George in 2024 stands on the ʔapsčiik t̓ašii (Ups-cheek ta-shee) bike path within Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ Territory at Pacific Rim National Park Reserve’s southern border. Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ Elders chose the cixwatin (eagle) because of its ability to watch over everyone.

Leo Touchie of Hitacu started creating his art as a young boy, inspired by seeing a picture of a killer whale. He honed his carving skills at classes taught by the late Ray Martin, put on by the Toquaht Nation.

Designs and motifs can be inherited, and are traditionally used for ceremonial occasions, often displayed on carved masks and headdresses. Dances and songs are also passed down with hereditary rights.

Finely woven baskets were originally used for storing and transporting items, and for trading. Some nuučaan̓uł artists now sell the baskets, sometimes weaving them to cover bottles or glass-ball fishing floats. They were originally created with natural dyes, but commercial dyes are now sometimes used to yield more vivid colours. Designs include whales, canoes, sea serpents and birds.

t̓uk̓ʷaaʔatḥ artist Mary McKay, who lived for many years at hac̓aaqis (Stuart Bay), was a master grass weaver. Her grandson’s wife, Charlotte McKay, carries on the tradition of both grass and cedar. Rose Cootes, Sarah Tutube, Gladys Sam and Marion Louie did grass weaving. Karen Severinson recalls taking her aunt, Rose Cootes, to the George Fraser Islands to pick the special grass for weaving. Ucluelet weavers of cedar include Rose Wilson and her son Brian. The nuučaan̓uł also weave cedar capes and hats.

Beading, over bottles or glass balls, or in intricate jewellery, features both traditional and modern design. Bessie Marshall, Molly Haipee and Faye Louie created beautiful loom beadwork. Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ artists doing beadwork include Cecilia Smith, Sarah Billy, Pearl and Sheila Touchie, and Rose Wilson. Lynette Dawson, long-time Ucluelet resident of Bonnechere Algonquin heritage, also does beadwork.

That the art not only survived but continues to thrive is testimony to the spirit and resilience of the Nuu-chah-nulth.

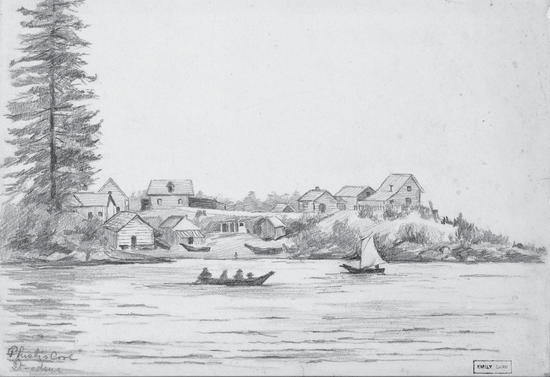

Emily Carr

Venerated BC artist and writer Emily Carr found inspiration in coastal landscapes and First Nations culture. Although she was documented visiting Ucluelet only twice, her name has a close connection with this place. The Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ of hitac̓u are said to have given her the name Klee Wyck, meaning “Laughing One.”

Carr first came to Ucluelet in the summer of 1898, to visit her sister Lizzie, who was volunteering at the Presbyterian mission school at hitac̓u. Emily was then twenty-seven, although in her memoir Klee Wyck she gives her age as fifteen. (Emily sometimes used poetic licence in the writing of her books.)

Emily used pencil and pen and ink to portray the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ people and their village surroundings in a realistic style. Later, after she met Canada’s famous Group of Seven, her work would reflect the influence of Modernism and Post-Impressionism.

Emily described hitac̓u in Klee Wyck: “Houses and people were alike. Wind, rain, forest and sea had done the same things to both—both were soaked through and through with sunshine, too.”5

Emily’s 1904 trip to Ucluelet came shortly after a five-year visit to England, during which she studied art and spent time in a sanatorium for a breakdown. Her return to Victoria was stressful and she sought a reprieve in Ucluelet’s coastal isolation.

Although there is no record of Emily Carr returning to Ucluelet after 1904, she made other journeys up and down the coast. In August 1929, she visited Port Renfrew on a sketching trip. While there, she stayed with my grandparents, Thomas and Annie Baird. My uncle Tom, who was thirteen at the time, later told me they all remarked on the fact that she didn’t bathe while she was there. Given the size of the family and the lack of privacy for bathing in the home, perhaps that was due to modesty on Emily’s part.

Arthur Lismer

One of Canada’s renowned Group of Seven, Arthur Lismer first came to Long Beach in 1951, and he returned each summer with his wife, Esther, for a six-week stay in the same cabin at the Wickaninnish Lodge. When the Wickaninnish Inn was built, the Lismers continued their visits, and their favourite cabin became known as Lismer Cottage. They frequently ate at the Inn. Mr. Lismer often picked small bouquets of wildflowers for his wife and put them in water at their table. When, at age fifteen, I started waitressing at the Wick, the very first table I waited on was the Lismers’. Flustered and nervous, I mixed up their breakfast order. They could not have been more understanding.

Mr. Lismer was immensely kind and gracious, and liked to gently tease. Sometimes he would sketch on bits of paper, depicting, for example, a sliver of pie under a mountain of ice cream when ordering dessert. Catherine Taron (née Mountain), who also waitressed during those years, reminded me of one of Mr. Lismer’s jokes; the servers’ protocol was to turn the cups right side up on the saucer, then lift the cup and saucer and pour the coffee. Mr. Lismer would say he needed the exercise of turning over his own cup. Catherine found this quite comical, given that he was always out hiking with his painting supplies in his backpack, and was obviously physically fit, even up into his eighties.

Now an accomplished artist, Catherine remembers Mr. Lismer’s encouragement. At the age of fifteen, while serving meals, she told him about her drawings. He generously showed her his favourite brushes and the paintings he’d done that summer. Catherine’s interactions with Arthur Lismer sparked her dream that one day she too would paint.

That summer visit, his sixteenth to Long Beach, was his last. He passed away the following year, in 1969. We who were privileged to meet him remember him fondly when we visit the beach at Lismer Bay, not far from where the Wick cabins once stood.

Fred Varley, another Group of Seven painter, also visited the west coast of Vancouver Island. His son Jim lived in Ucluelet with wife Carol, in a log house near Little Beach. Carol’s ex-husband, Albertus “Ab” Van Amerongen, lived in a cottage on their property. Ab was a local character who wore lederhosen and took local youths on challenging nature hikes. Jim and Carol were music lovers, and I recall pleasant gatherings during the 1970s and ’80s, sitting around their acorn fireplace, sipping wine and listening to classical music while gazing out at the ever-changing Pacific.

Other talented Ucluelet painters inspired by their surroundings included Josephine Littleton (née Binns) and her son Paddy, and commercial fisherman Art Hutchinson, who captured glorious sunrises on his early morning trips to the fishing grounds.

An Assemblage of Artists

Long-time west coast resident Marla Thirsk has earned the moniker “Ukee’s artist.” Her paintings grace local walls both inside and out. She created the first poster (and many more) advertising the annual Pacific Rim Whale Festival, as well as posters for myriad local events. Marla’s sought-after work, including drawings, paintings, sculptures and fabric art, ranges from the realistic to the whimsical, and she has happy customers worldwide.

A gifted artist, Signy Cohen not only paints the west coast, but is renowned across Canada for her portrait paintings. Signy promoted artists for years in her Tofino gallery, and when she closed it, she continued to do so in her Ucluelet gallery, Reflecting Spirit. Many talented local artists are showcased both in Signy’s gallery and in the Orange Door Gallery, an initiative of the Pacific Rim Arts Society. PRAS was incorporated on November 20, 1970, under the name Long Beach Arts Council. In August 1985, the name was changed, but the institution is still the same, making it one of the longest-standing arts organizations in BC.

PRAS promotes all the arts, but early on the main focus was music. A dynamic duo, Adrienne Shannon and Joy Innis, visited the coast and loved it. They moved here and performed as the piano duo Palenai, meaning a symbol of unified diversity. Joy and Adrienne taught piano to local students of all ages, and Joy bravely took on the community adult band, which had been ably taught by John Montgomery, a popular school music teacher who transferred to another community. Local concert bassoonist turned log scaler Tom Petrowitz also taught the band.

Starting in 1986, PRAS put on a summer chamber music festival under the leadership of Palenai. The faculty of distinguished musicians included the renowned American Piano Trio. When Joy Innis was asked “Why chamber music?” she responded: “This type of music reflects the timelessness of this environment.”6

Then mayor Bill Irving commented that the Pacific Rim Summer Festival helped bring Ucluelet and Tofino together during controversial times.7

Joy and Adrienne co-ordinated the festival, supported by a team of volunteers. Margaret Mazzoni and Pam McIntosh were the driving force behind the Summer Festival. During those busy summer weeks, musical notes filled Ucluelet’s fresh sea air. Visiting students were billeted throughout town and sandwiched sightseeing and socializing between master classes, practising and performing. The festival included multicultural programming—we had the opportunity to billet choirs from around the globe.

We raised funds unfailingly for the cause, many of us trekking from Ucluelet to Green Point in a walkathon to buy the community a grand piano, key by key. We planted trees in torrential downpours, coming home sodden and sooty from scrabbling up steep, slash-burned hillsides with our bags of seedlings. Generous sponsors kept the festival thriving for many years, until circumstances changed and Palenai’s career took the duo back to city life.

From a primarily music-based festival, the Pacific Rim Summer Festival evolved to what PRAS president Mark Penny called “a celebration of the arts,” with the addition of “various forms of dance, poetry and visual arts.”8

PRAS originally had the Christmas Craft Fair under its umbrella. When it gave that up, Marla Thirsk co-ordinated the fair for many years. PRAS continued with ArtSplash, its long-running yearly non-juried art show, and added more events, including the annual Cultural Heritage Festival, the Carving on the Edge Festival, and the Artists’ Walk on the Wild Pacific Trail, featuring the work of painters, sculptors, musicians, dancers and other talented artists at scenic viewpoints along the trail. PRAS, now with a home base in its Orange Door Gallery, continues to flourish through the work of artist volunteers under the creative leadership of its executive director, pyrographic artist Kelly Deakin.

Going Walkabout

Mike Camp’s sculptures stand tall and proud at the corner of Peninsula and Bay. His medium of choice is stainless steel “because of the lasting impact it creates.”9Raven Lady has posed gracefully for over thirty years, none the worse for wear (although she did topple over one year and was trucked to then owner Ron Burley’s property, before being reinstalled). Raven Lady has since been joined by Surfer Girl, a massive wolf and Wanderer’s Tree, festooned with oyster shells. Going walkabout through town will also reveal ten colourful murals by Marla Thirsk. The mural at the back of Ukee Dogs restaurant features a collection of local characters.

Theatre and Dance

Early on, locals formed a theatre group, even going “on the road” to Tofino. High school teacher Roger Sparks’s students earned accolades at out-of-town drama festivals. Local youth continue to show dramatic flair in both the yearly Missoula Children’s Theatre program and the Glee musical theatre program put on by Courtney Johnson and Sarah Hogan. Adults get their chance to shine in dinner theatre productions, created by local boat skipper Jacqueline Holliday along with fellow innovative spirits Courtney and Sarah.

When the Noble sisters Anne (Gudbranson) and Sally (Stonehouse) moved to Ucluelet as teenagers in 1960, they brought their dancing skills with them. A few of us kids briefly took ballet lessons, but were deemed more suited to Highland dancing. We even entered a Highland games competition in Victoria—I have a vague memory of accidentally kicking a sword off the stage.

Paula Ross, who founded Vancouver’s first contemporary dance company in the mid-1960s, brought the gift of dance to Ucluelet when she moved here with her husband, Al Fukushima, and their children to pursue fishing and oyster farming.

She founded the Paula Ross Dance Society in 1973, opening a portal to the world of dance for local youth. When Paula and her family moved away, the dance program continued under the society’s umbrella, with dancing teachers such as Gabrielle Springett and Janine Wood. Dance teacher Barbara Ellen Camp tragically passed away far too soon, but left a legacy of creativity and joy. The Paula Ross Dance Society maintains opportunities for youth and adults to be involved in dance and the performing arts. And the unique landscape, culture and history of Ucluelet and the surrounding area continue to inspire a wide range of artistic expression.