Chapter 18: Logging Heyday and “Nay Day”

When Europeans first arrived on the West Coast, they found forests that had been growing for close to fifteen thousand years, having reclaimed the glacier-scoured landscape.1 The mainly coniferous trees, notably cedar, hemlock and Sitka spruce, thrive in temperate rainforest. Those early Europeans felled trees mainly for spars or masts for their sailing ships, choosing trees that were straight, strong and at least one hundred feet tall.

Logging in the Barkley Sound area began in 1860, when Captain Edward Stamp built a sawmill at what is now Port Alberni. In 1861, the first lumber shipment left there for Victoria. By 1862, when Gilbert Sproat took over the sawmill, lumber and wood for spars travelled worldwide. It was, however, a short-lived enterprise; by January 1864 all the easily accessible forest had been logged, and Sproat closed the sawmill. Timber accessibility would later be addressed in an innovative way, at Port Albion, across from Ucluelet.

Sutton Lumber Company

The Sutton brothers ran a sawmill at Lake Cowichan and were looking for marketable timber. In 1890, they found what they wanted at Kennedy Lake, near Ucluelet. Will Sutton later addressed an avid audience in Victoria: “I was interested in some timber land at Kennedy Lake, where there is very large cedar. To give you some idea of the size of the cedar trees down there, when we were running a survey line one day, I sent a man back to pick up something that was left behind, and as he had only been gone a few minutes, I noticed by his demeanour that there was something wrong, and he said: ‘I thought I was going the other way.’ I went along with him to ascertain how it had happened. I found that he had become lost in going around a big cedar tree, and came back on his track. [Laughter.] That tree measured 45 feet in circumference. [Applause.]”2

As well as acquiring holdings around Kennedy Lake, the Sutton brothers pre-empted a larger area on Ucluelet Inlet’s east side. There, in what was later known as Port Albion, they set up a sawmill under the name Sutton Lumber Company. The census of 1891 lists both brothers as loggers employing six men in their sawmill. (The advertised wage for the workers was $2.50 per day.)

By 1895 Will Sutton had devised an efficient way to transport felled timber to the water. Hydro-powered electric motors would quickly draw logs along skids to the waterway, giving easy access to an “immense stock of timber…cut from a comparatively limited area.”3

By the end of 1902, the Sutton brothers had sold their company shares to the Seattle Cedar Lumber Manufacturing Company, who then acquired more timber leases. The company built a large sawmill on Meares Island, a site which would be known in the distant future as ground zero of the battle between preservationists and logging corporations. In 1907, a massive number of teredos (shipworms) infested log booms and dock pilings, and the sawmill closed down. The timber rights were later sold.4

Early Forest Conservation

Will Sutton was a conservationist who, as early as 1910, recommended formation of a provincial bureau to “supervise all matters relating to our forests.”5 His lobbying at the Fulton Royal Commission of Inquiry on Timber and Forestry helped lead to formation of the Forest Branch. In 1912, H.R. MacMillan was designated the first chief forester of BC. He would later be a key player in logging on Vancouver Island’s west coast.

With the onset of World War I, Will’s forestry proposals went on the back burner, not to be considered until around 1921. Clearly, some of his warnings were deemed alarmist. Change came slowly. Forestry practices continue to be debated.

When Ucluelet settlers felled trees, it was usually to clear their property. Early photos of Ucluelet show a cross between stump farm and clear-cut. The settlers, mainly from farming and ranching backgrounds, used the timber to build their homes, outbuildings and fences.

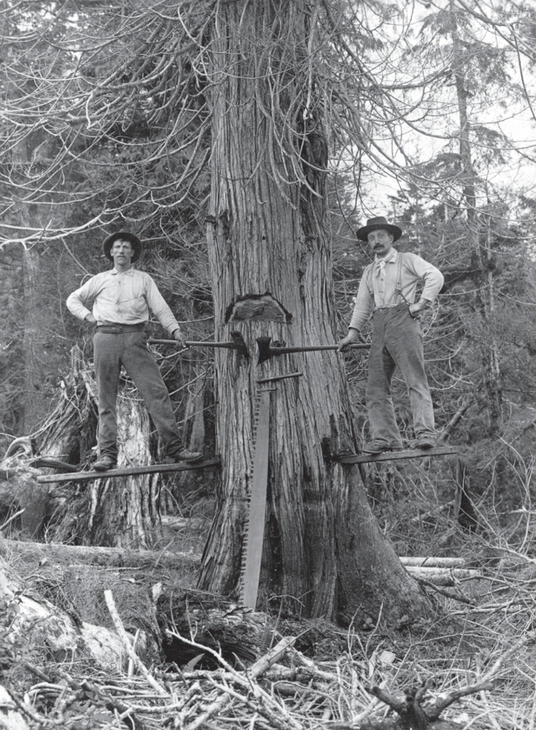

From the late 1800s to the 1940s, loggers used double-bitted axes and crosscut saws. Logs were originally hauled by oxen, mules and horses, a method largely replaced by steam-powered machinery in the 1890s. Railway logging used steam locomotives to move timber. Widespread adoption of the internal combustion engine in the 1920s replaced steam power with machinery fuelled by gas or diesel. This meant the arrival of truck logging.

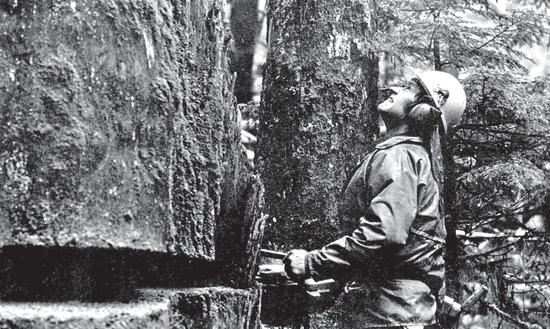

Another key technological change was the chainsaw. Not all loggers were impressed. Olaf Fedje, a founder of one of BC’s oldest and biggest falling contractors, said that “people couldn’t stand the noise…Hand falling was so quiet. All of a sudden this terrible monster came along…A lot of people lost their hearing because of that noise.”6 He added: “But it was lighter work. It wasn’t the heavy slogging. The younger people took to it quite readily. The old timers fought it tooth and nail.”7 Fedje believed chainsaws were safer because “a guy with a chainsaw does the work of three or four people, so that cuts your accidents down right there. There’s only a quarter as many people out there to get hurt.”8

The efficiency of chainsaws was undeniable; crosscut saws were hung on garage walls or tucked away in basements, and brought out only for logger sports competitions.

Ed Eason Trucking

Ed Eason started his business by building a logging truck out of a dismantled army truck, and he went on to create one of Vancouver Island’s biggest contract trucking businesses. Before Ed, Alma Smith ran a logging truck business out of Ucluelet. Roy Saunders and his sons later did contract trucking.

The logging trucks hauled logs during the day. At night, wooden contraptions were put on the back of the trucks and used to build roads with dumped gravel. Originally, the logging roads were all plank roads. A plank road going out to the swimming beach at Kennedy Lake had been put in during World War II, when the air force had a camp there.

A larger-scale logging industry started up in Ucluelet after World War II. Wilfred Thornton leased some of his property at the head of Ucluelet Inlet to Harry McQuillan of the North Coast Timber Company, a truck logging outfit employing around 150 men. Wilfred’s sister-in-law Elsie Hillier described the logging activity: “The logs are brought down by trucks and dumped into the water. Small tugs sort and tow them to the landing works where they are loaded onto flat booms. Tugs from town come in and tow these out to sea every few days.”9

This was a long way from 1904, when Herbert Hillier and William Thompson logged two booms of logs of a hundred thousand feet each and sold them to the Ucluelet mill for six dollars per thousand feet.10

The Maggie Lake Timber Company and Taylor Way also logged in the Ucluelet area. In 1947, the H.R. MacMillan Export Company purchased local timber holdings to supply wood to their Harmac plant near Nanaimo. An article in the September 1947 issue of the Harmac News extended a “cordial welcome” to the 140 employees of Kennedy Lake Logging Company Ltd. and described the newly available timber as including “a high proportion of cedar around the lakes with hemlock and balsam common on the higher slopes.”11

When Kennedy Lake Logging Division was set up, my father was approached to become camp superintendent. Dad had a long working history in logging and fishing. After some discussion with Mom, Dad accepted the position, once more switching from commercial fishing to logging. In the late 1940s, my parents sold their Victoria home and moved to Kennedy Lake Camp, along with my brothers Robbie and Ian.

Kennedy Camp Kid

My memories begin in the logging camp. I was born in 1951 in Victoria, as my mother had experienced complications when my brothers were born and didn’t want to risk giving birth in our isolated area. Soon after my birth, Mom and I came home to Ucluelet by coastal steamship. From the Whiskey Dock in “downtown” Ucluelet, it was an eight-kilometre drive on a gravel road to Kennedy Lake Camp.

Wilfred Thornton, widowed, lived with his mother-in-law, Kate Karn, on their property close to the bungalows, and farther away from the working camp. Harold and Mavis Thornton, Wilfred’s son and daughter-in-law, lived next door to us.

Later on, three large houses were built on a rise behind the bungalows, and we moved up the hill to the middle house. These tall houses were painted forest green with red trim and had identical layouts. My third-floor room looked out over the logging camp and the harbour. My brothers shared the bedroom across the hall. Their wooden fire-escape ladder gave them a convenient way to sneak out for “adventures.” The house seemed palatial after our little bungalow down below. Next door lived the Smith family, Naida and Dudley and their six kids. On the other side was the Crawford family.

On the green space between the two rows of houses we spent a lot of time reaching for the sky on several massive swings. There was also a springy teeter-totter. My brothers liked to land with a bang, trying to bounce me off.

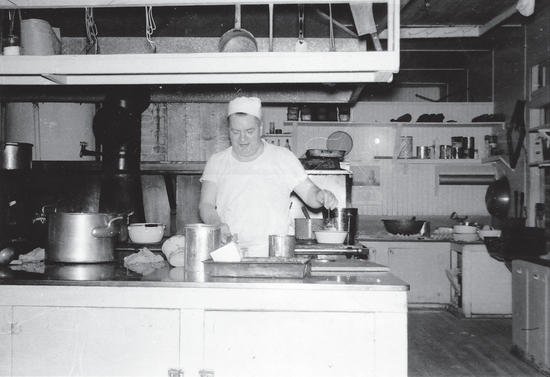

Thursday was doughnut day, and we kids made sure to visit the cookhouse. Once we started school, we’d stop by every Thursday for a doughnut on our way home. Joe always had a paper bag of chocolate-covered doughnuts to send home for my dad.

The cookhouse was a fun place to be, and I liked helping there. My mom asked why I complained about doing dishes at home but was always happy to dry dishes at the cookhouse, and help Jimmy Kabish, the flunky. The doughnuts, the hotcakes (which, if there were any left over from breakfast, were great slathered in butter and jam) and other treats no doubt had something to do with it. I also liked feeding bread crusts to the roughly thirty raccoons hanging out behind the cookhouse.

Most loggers arrived at the cookhouse wearing cork (caulk) boots and slid their booted feet into wooden soles held on by canvas straps to avoid gouging the floor. We kids loved trying to walk around with those big wooden contraptions on our feet!

On our way home from school we also visited the canteen, a source of candy and pop. My favourite pop was cream soda—I don’t know if that syrupy red drink still exists. John Campbell, the camp first-aid man, ran the canteen. He was a friendly fellow who whistled almost constantly.

Being a camp kid was never boring. We built forts, played on the log booms (although Mom forbade it) and sat in the back of Dad’s pickup, roaring along dusty logging roads—no seat belts for us back then. Both of my brothers drove on the logging roads as kids, although I had to wait to be on Long Beach for my underage driving.

Terry Smith, like my brothers, drove out in the woods. He and his friend Jimmy Hammond sometimes went to work with Jimmy’s dad Norm, and took turns driving around while Norm tended to his job overseeing two sides of a logging show (active timber harvesting operation), quite a demanding task. Four long whistles meant the boys had to bring the truck back. Terry was eight years old at the time.

One memorable night, there was a massive fire adjacent to the harbour, not far from the MacMillan and Bloedel homes. My mother bundled me up and hurried me and my brothers down to watch from a safe distance, as my dad went into the burning building and drove a few trucks out. The old shed had housed vehicles belonging to Jerry Brock’s trucking company. Apparently, my younger brother and several friends had played with matches, which ultimately set the place ablaze. They were later interviewed by insurance people and fessed up to their unintended crime. This must have been a relief for the trucking company, which had been under suspicion of arson for insurance fraud purposes.

We spent lots of sunny days at Kennedy Lake. One summer, a “grey goose” (a blunt-nosed wooden boat with a small ramp at the front) was being used for transporting logging crew and towing bags of wood. Our family and the Smith family went across the lake in it for a picnic at Sand River. Terry Smith said of the high-powered craft, “It leaked like a sieve but had this massive pump that got rid of the water as fast as it came in.”

As camp superintendent, my dad had to put in office time, but preferred being out in the woods. Whenever Mom asked what he wanted to take for lunch, his answer never varied: “A cheese sandwich and a drink from the creek.”

When we camp kids reached school age, we walked out (along what is now called Thornton Road) to the highway to catch the school bus. I remember the driver, Mr. Singleton, as a kind and patient man. By the time he reached us, the bus was loaded with high school students from Tofino, and he’d already dealt with his stress by pulling the bus over to the side of the road and getting out to have a smoke. (Some of the bigger kids joined him.)12

Looking back, I feel sorry for him. Some of the kids were little hellions, and we all used to sing a ditty about “Baldy, Baldy Singleton, King of the Wild School Bus!” In later years, when my husband came home from his part-time job driving school bus and recounted the shenanigans of a few especially rambunctious kids, I’d nod knowingly and send Mr. Singleton a mental apology for any past disrespect.

The walk out to the highway to catch the bus was only about a kilometre and a half, but we were frequently reminded to watch for cougars and stick together. One morning, a friend and I decided to play hooky and snuck into the bushes instead of catching the bus. Before long, my mom got a phone call saying I had not turned up at school. Mom didn’t drive, so she had Dad radioed out in the bush. He was not impressed by the time he tracked us down!

When I was in Grade Three, Dad had a house built in town in the middle of George Fraser’s garden, and we moved out of the green house on the hill. There were lots of pluses to living in town. We had our own wharf, and Dad built me a little rowboat so I could row around the harbour. The school, the library, the few stores, everything was in walking distance, but I missed living at Kennedy Camp. Luckily, we still had access to Joe’s doughnuts, though not on such a regular basis.

One sad note for me was the loss of our calico cat, Judy. We brought her with us when we moved into town, but she missed her old domain and high-tailed it back over the eight kilometres to Kennedy Lake Camp. We retrieved her several times, but she always went back, so she eventually became once more a camp-based cat. Our springer spaniel, Skipper, remained faithful to the family and stayed at our new home in Ucluelet.

Alliance Holdings

When MacMillan and Bloedel arrived, they looked for housing options for their employees. Next to a dirt path that would later become Bay Street were four duplexes built by the armed forces in 1943 to house officers of the Canadian Scottish Regiment. With the forces pulling out, MacMillan and Bloedel bought the buildings, which were on land leased from the Littleton family. The company then bought four more duplexes, barging them in from Bremerton, Washington, to set up on the bottom row of the housing complex.

Alliance Holdings still stands, a unique and historically important neighbourhood with preserved green space, in the heart of Ucluelet.

Mac & Blo: What’s in a Name?

Logging would become a contentious issue on the West Coast, with the spotlight on major logging corporation MacMillan Bloedel Ltd. That company’s roots go back to 1911, when a Bellingham lumberman named Julius Bloedel, along with two silent partners, formed the company of Bloedel, Stewart and Welch. The H.R. MacMillan Export Company was formed in 1919 by Harvey Reginald MacMillan.

In 1951, the two companies merged, becoming MacMillan and Bloedel Ltd. The new company gained worldwide recognition as “one of the largest lumber consortia in the world.”13 In 1960, MacMillan and Bloedel Ltd. merged with the Powell River Company (created in 1909, and the world’s largest newsprint mill) to become MacMillan, Bloedel and Powell River Ltd. In 1966, the name was shortened to MacMillan Bloedel Ltd., abbreviated to MacBlo or MB. Headquarters were in “the Big Smoke” (Vancouver), in a twenty-seven-storey structure referred to as “the Ivory Tower” and “the Concrete Snag.”

The Heyday of Logging

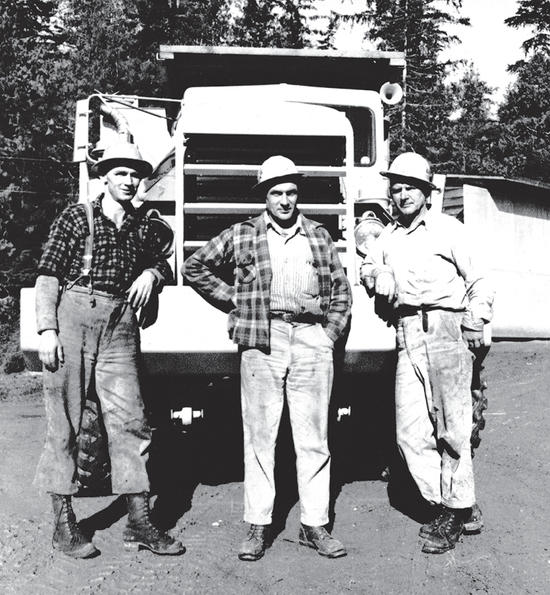

Logging in the Ucluelet area started in the 1940s, came to the forefront in the 1950s and was still going strong in the 1980s. It was evident just by driving around Ucluelet that this was a logging town. Crummies (the vehicles that transported loggers to and from work) were a regular sight, with their classic red-and-white paint job. There was lots of work in the woods, either full-time or as summer jobs for students. Paycheques were regular, except during woods closures for snow or for extreme heat causing fire hazards. Sometimes sections of woods were closed because of species-habitat concerns—as when, for example, engineering crew member Dan Tuzo spotted an endangered Vancouver Island marmot. The area was protected from logging, with Dan thereafter known as “Marmot Dan.”

The occasional strike led to depleted bank accounts, but all in all, MacBlo was a reliable income source. Logging was regarded as a profession, “a job one does to feed the family, pay the rent, and keep the wolf from the door.”14 Many local loggers were from long-time logging families and proud of their profession.

Millstream Timber also logged in the area, under contract to BC Forest Products. In the early ’70s, Millstream provided housing for their employees by creating Millstream Subdivision. The clear-cut, bulldozed site looked like a big gravel pit. Surplus houses available because of the expansion of the Vancouver airport were barged in from there. Rumour has it one of them ended up in the saltchuck. Two of the three green and red MacBlo houses were moved across from Kennedy Camp. Jack McKercher and Olaf Fedje each built a new house. Employees rented the barged-in houses. Then the loggers set about putting in wells and septic tanks, the proximity of some of these improvements creating a less-than-ideal water supply. Nearby Kvarno Island was also logged, with one tree, home to an eagle’s nest, left standing.

When logging started to phase out, the employees had the option to buy the rental houses. Many of them did so and independently improved on infrastructure, and Millstream gradually transitioned to the bedroom community it is today.

Johnny Gerbrandt also did contract logging, and Fedje and Gunderson were falling contractors.

There were so many Ucluelet loggers, and I wish I could tell all of their stories. Here are a few.

The Smith Family

Terry Smith recalls arriving in Ucluelet aboard the Princess Maquinna in 1946. His grandfather, Harry Smith, worked as a timber cruiser here. Terry’s father, Dudley, had been demobbed after the war, worked in a shipyard, and decided Ucluelet was an appealing change.

Dudley, wife Naida, Terry and Mike (in a buggy) headed up the Main Street Hill to their little rental home. There was an outhouse and a water pump out the back, somewhat of a change from their Vancouver abode. Murray Payne would later buy that house and add onto it for himself, wife Gloria and ten children.

From there, the Smiths moved into M&B staff housing at the army camp, and then next door to us at Kennedy Lake Camp. Tragedy struck in 1958. It rained heavily that winter, and in January there was one metre of rain. There was a camp for construction workers at Kennedy Lake, at the present boat launch. The incessant rain caused concern that a logjam above the camp would let go and wash them out. They couldn’t be reached by road, as it was flooded. Dudley set out in a skiff, carrying powder to clear the jam, and tragically drowned. The devastating accident left Naida with six children ranging in age from four to fourteen.

With assistance from M&B and village members, a new home was built for Naida and family in Ucluelet. There, Naida raised her children, tended a productive garden, raised chickens, baked the most delicious bread, read our tea leaves, did weaving and ceramics, volunteered in the community and ran the elementary school library. She was an amazing lady.

Eldest son Terry has had a long and varied career in the logging industry. Starting as a teenage flunky in the cookhouse, he covered the gamut of work in the woods and on the boom, then took on several managerial roles. After Kennedy Camp closed down, Terry continued in the industry with projects such as site remediation. He is clearly well-qualified for his volunteer position of chairman of the Barkley Community Forest Corporation.

Earl Mundy

Earl Mundy grew up in Hitacu, fishing from an early age with his dad on the ten-metre Barnacle Bill. In his teens, Earl decided to switch to logging, which he considered an 8−4:30 job, whereas fishing was a twenty-four-hour-a-day job.

Earl started at Kennedy Lake Division as a plumber’s helper, then set chokers for nine months before finding his true calling, operating a loader. Earl worked for MacBlo for forty-two years, loved his job, and was renowned for his skill. My husband said watching Earl work with a log loader, especially the super snorkel, was like watching a ballet, every move smooth and precise.

Earl was sometimes reprimanded for not wearing a hard hat; he thought they brought bad luck. He had some unfortunate accidents, but his good luck outweighed the bad—some people said Earl had nine lives.

After one of these close calls, MacBlo flew Earl by helicopter to Squamish to check out a new loader and give it his thumbs-up. The new machine had air conditioning and a plaque engraved with Earl’s name.

As well as working as a loader operator, Earl drove crummy and liked to speed. One logger recalled a wild ride through the woods as Earl drag-raced another crummy, headed for home. If passengers complained, Earl’s answer was, “Well, I got ya here, didn’t I?”

Earl and the other loggers from Hitacu had to cross the harbour by boat before travelling in crummies out to Kennedy Lake Division. When they refused to go to work until they were assured a road would go through, connecting Hitacu to Kennedy Camp (and therefore also to Ucluelet), an agreement was reached in short order. Earl later overheard a politician taking credit for the new road and quickly set him straight.

The War in the Woods

The loggers felt secure in their lifestyles in Ucluelet, where many of them grew up, and where they planned to live out their years. But a war in the woods hovered on the horizon.

Both MacMillan Bloedel and BC Forest Products logged near Ucluelet and Kennedy Lake. They then looked farther afield, acquiring timber rights on Meares Island and other areas in Clayoquot Sound. There were already small, independent companies logging in Clayoquot Sound, many of them based in Tofino. Most of their logging was done out of view, although in 1954–55 the south face of Lone Cone Mountain, directly across from Tofino, was clear-cut. “It was a terrible scar,” long-time Tofino resident Jacquie Hansen recalled. “But it’s all grown over now.”15

The small logging outfits had been tolerated, and in some cases welcomed. But when forestry giant MacMillan Bloedel made a move, dissension soon followed.

In 1979, the grassroots group Friends of Clayoquot Sound (FOCS) was formed in Tofino, because of concern about the rumoured logging of Meares Island. In 1980, at the request of Tofino municipal council, the BC government formed the Meares Island Planning Committee. In April 1984, FOCS organized the Meares Island Easter Festival, where Moses Martin, Tla-o-qui-aht Chief Councillor, declared Meares Island a Tribal Park.

The first actual blockade occurred on November 21, 1984, at Heelboom (C’is-a-quis) Bay on Meares Island. Early the previous month, up to thirty spiked trees had been found in the area. (Contact with a metal spike or nail in a tree can cause a chainsaw to kick back, maiming or killing fallers or buckers. Spiked trees can also cause serious accidents in sawmills.) No one took responsibility for the spiking. Local doctor Ron Aspinall, a strong opponent of logging on Meares, said he’d “heard of protestors putting 15-20 cm corkscrew spikes into trees near Heelboom Bay.” He described the whole town of Tofino as “hopping mad” about the proposed logging.16FOCS spokesman Michael Mullin emphasized a peaceful protest stance, adding that he “would not spike trees himself,” but acknowledged there were radicals “determined to resist this at any cost.”17

Logging opponent Carl Hinke agreed to speak for an unnamed group of tree spikers, writing in a letter to MacMillan Bloedel: “Spiked, the land lies living; logged, the land lies dead.” He told a reporter that two boxes of six-inch and ten-inch spikes—about nine thousand in all—had already been driven into Meares Island trees.18

The company workers arriving at Heelboom Bay aboard the Kennedy Queen were met by a flotilla of anti-logging protestors. More protestors lined the shore. Moses Martin informed the loggers: “This land is our garden. If you put down your chainsaws you are welcome ashore, but not one tree will be cut.”19 Michael Mullin said FOCS had been assured by the International Woodworkers of America (IWA) union that fallers would not drop trees near people because “they’re not allowed to jeopardize people.”20 He also offered an open invitation to “everyone in the province to come and camp on Meares Island.”21

Next came injunctions and counter-injunctions, culminating in a court decree on March 27, 1985, that all logging on Meares Island must stop until resolution of First Nations land claims. However, logging in other parts of Clayoquot Sound continued. In 1988, Fletcher Challenge (a New Zealand–based company that bought out BC Forest Products in 1987) was spotted building a logging road into Sulphur Passage. When more protests ensued, it logged a less visible area of Clayoquot Sound. Dissension continued, attracting worldwide media attention.

In 1988, MacMillan Bloedel employed 210 people in the Ucluelet area, contributing some $8 million annually to the community. Paul Varga, then manager of Kennedy Lake Division, stressed the importance of reforestation. During National Forest Week of 1988, MacBlo planted its seventy-one-millionth seedling.22 The environmentalists were not swayed by tree planting numbers.

Frustration mounted, and in April 1991 protestors burned Kennedy River Bridge, stopping access to a logging site and putting 210 loggers out of work.

International Forest Products, a BC logging company, entered the picture in April of that year, working with First Nations and logging on a smaller scale. Meanwhile, BC worked on a Forest Practices Code with a more environmentally friendly focus. This code would become law in 1995. It wouldn’t be soon enough.

Government-appointed committees attempted a solution. In 1992, sixty-seven hourly and nine staff workers at Kennedy Lake Division lost their jobs, foreshadowing what was to come. MacMillan Bloedel cited reduced allowable annual cuts as the reason for the job terminations.23

By early 1993, the rallying cry to preserve Clayoquot Sound echoed around the world. Media attention mushroomed when Greenpeace joined the cause. Things came to a head when BC Premier Mike Harcourt landed atop Radar Hill in a helicopter and stepped out to announce the government’s decision. The gist of his Clayoquot Sound Land Use Decision message was that nearly two thirds of Clayoquot Sound would be open to logging, with a portion of it in a “limited” manner. One-third of the sound would be protected.

Harcourt’s announcement served as a call to arms for environmentalists. On May 16, 1993, MacMillan Bloedel security worker Doug Fraser was doing his rounds. At 11 p.m. he noticed fuel soaked into the surface of Clayoquot Arm Bridge. Wood burst into flames around his truck, but he was able to drive off. Fraser heard a speedboat leave from under the bridge, and radioed police, the Ucluelet Volunteer Fire Brigade and MacMillan Bloedel. The fire was extinguished, and RCMP intercepted three suspects in a van at a Tofino roadblock. The three men were charged. (Soon after, one of them resigned from Friends of Clayoquot Sound, which he had helped found, and which advocated a strict non-violence policy.)24

In June 1993, FOCS set up a camp on Stubbs Island, providing training sessions on civil disobedience and non-violent protest, with opportunities to learn about “the rainforest and media skills.”25 Participants arrived from afar, including California and Germany. Another “action camp” was held in Vancouver’s Stanley Park.

Faller Harvey Nauffts recalled a nude, spaced-out protestor attempting to incapacitate logging equipment by cutting through hydraulic lines. When the loggers tried to protect him from incapacitating himself (hot oil under extreme pressure can cause severe bodily damage), the protestor accused them of harassment.

FOCS set up its “Peace Camp” on July 1, at a logged area several kilometres from the Ucluelet–Tofino junction. The clear-cut had been slash-burned by Millstream Timber, and was an ideal eyesore for the protestors’ mission, since all west coast traffic had to drive by the spot. The Peace Camp’s high visibility, combined with extensive media coverage, drew hordes of protestors. It is estimated that between ten thousand and twelve thousand people passed through the Peace Camp during the roughly three months it was open.26

Blockades began at Kennedy River Bridge on July 5, 1993. An article in the Westerly News described the morning routines at the bridge: “Arrival of MB and the reading of the injunction, the protest, the arrests, loggers through and on the way to work.” The court injunction related to the banning of protests in Clayoquot Sound. Some protestors volunteered to be arrested each day while the rest stood by, bearing witness. Local supporters of the loggers observed, at times encouraging the protestors to leave as tensions ran high. Those arrested, amounting to eight hundred by summer’s end, were transported to Ucluelet for processing.

On July 15, 1993, Australian rock band Midnight Oil put on a concert at the Black Hole Peace Camp in support of the protestors. Estimates of the number of attendees vary from three thousand to five thousand. Renowned environmentalist David Suzuki reportedly sat in the front row. Robert Kennedy Jr. also appeared on the coast to combat the logging. Hollywood celebrities, including Robert Redford, Barbara Streisand, Nicole Kidman and her then husband Tom Cruise, showed their support with glossy media ads.

What did not gain much media attention happened after the protestors decamped in October 1993. Ucluelet and Tofino locals, including loggers, cleaned up a heap of refuse at the Peace Camp. Mike Morton said the mess included pop and beer cans, tarps, clothes and an old bathtub near the stream. He also described finding three wooden toilets atop unfilled holes. A FOCS member was quick to say the site had been left “in better shape than we found it.” The seventy-five residents who did the final cleanup begged to differ.27

Reporter Eve Savoury reflected on the loggers’ reactions to the protests, describing them as “angry…out of their depth, deeply frustrated, and probably, deeply anxious. With good reason.”28 Many loggers viewed not only their jobs but also their history and way of life under attack, with many of the attackers judging from afar.

Rendezvous ’93

A counter-protest took place in Ucluelet in August 1993 to show support for local loggers and their families, and for the future of logging in BC. The two-day gathering was held on the school fields, with a crowd of around five thousand attending. Loggers arrived from across the province, including a parade of at least sixty logging trucks and hundreds of cars, many with bumper stickers proclaiming “Hug a logger. You’ll never go back to trees.” Attendees sported yellow ribbons and yellow T-shirts symbolizing their hope for compromise. A huge cairn was constructed from rocks brought by attendees from across the province.

First Nations dancers and drummers welcomed the crowd. The movement’s theme song, “Give Change a Chance,” was on replay as the Mars water bomber from neighbouring Port Alberni roared overhead. Singers and musicians contributed a folk festival ambience. Speeches encouraged the government to stand firm on their decisions, an outcome that was not to be. Former NDP leader and then federal MP Bob Skelly spoke eloquently. Former IWA leader Jack Munro, then chairman of the Forest Alliance of BC, arrived on his Harley-Davidson to expound in his typically colourful fashion. Validation and hope buoyed the crowd.

For local loggers and families, the gathering provided a temporary release from ongoing stress. Many had a chance to visit with out-of-town family and friends. The anti-logging movement accused MacMillan Bloedel of paying their workers to attend the rally, issuing a press release stating this untruth. This discounted the sincere concerns of the forest workers about their livelihoods, and their hopes for a viable solution to the impasse. Afterwards, some attendees expressed frustration at the lack of media coverage, compared with the almost daily attention focused on the anti-logging movement.

Premier Harcourt and cabinet were invited no-shows. Rendezvous chairman Chris O’Connor commented: “There has been an Elvis sighting in the crowd, but there hasn’t been a single sighting of a BC cabinet minister.”29

The Suits

Local loggers and supporters vented their frustration when two busloads of over a hundred professional and business people arrived on September 1, 1993, to support the anti-loggers. The buses had been detained for over three hours near Port Alberni, surrounded by close to three hundred pro-logging activists, who let air out of tires and tore posters off the buses. When the “well-dressed if somewhat bleary-eyed protestors from the buses” finally approached the protest line, they were met by around two hundred logging supporters, mainly from Ucluelet. Roadside debate ensued, with local logger Mickey Ralston looking dapper in a sports jacket and tie, to make the point that he, like them, deserved employment. The Victoria group sat around a fire at the Peace Camp, eating breakfast and talking strategy with the environmentalists. As they boarded the buses mid-morning to head back to the city, Ray Shore, one of the bus drivers, commented: “I don’t think it’s a good idea to play politics out in the middle of a public highway.”30

School Days

As tempers flared and emotions ran high, Ucluelet Secondary School principal Dave Milligan banned discussion of the logging conflict during school hours. Ucluelet Secondary School served the students of Ucluelet, Tofino and surrounding areas. Many of the kids were dealing with a lot of War in the Woods–related stress at home, and a break from it at school created emotional space. During this period, my daughters spent time with their Tofino friends, visiting back and forth between homes. The kids all handled the situation with maturity and empathy. My husband and I were really impressed.

Advocacy groups like Share the Clayoquot Society, formed in 1989 under the Share BC umbrella, voiced concerns about land and resource use. In a letter to the editor of the Alberni Valley Times on March 6, 1990, chairman Mike Morton wrote: “it is not a jobs vs. environment issue, it is a jobs and the environment issue.” Advocacy continued with Yellow Ribbon Day, when, on March 21, 1994, an estimated twenty thousand workers and supporters gathered outside the Parliament buildings in Victoria for the largest rally ever seen at the BC legislature. The yellow-ribbon wearers lobbied for a balanced land use strategy for the island, rather than an all-or-nothing response.

The Commission on Resources and Environment (CORE) sought a consensus-based agreement by the stakeholders. The CORE report, released in 1994, included recommendations for improved logging practices and the establishment of a biosphere reserve in Clayoquot Sound. It also reaffirmed the need to make decisions by consensus at a “regional table.” Reactions to the report ranged from optimism to disillusionment.

The Clayoquot Sound Scientific Panel was appointed by the BC government to develop guidelines for sustainable forest management and logging. Their report, released on May 29, 1995, elicited differing opinions on what constituted adherence to the recommendations. Waning logging options continued to decimate jobs.

There Is No Tunnel

In 1993, MacMillan Bloedel’s Kennedy Lake Division employed several hundred people. In 1996, they were down to eighty-five employees who had worked one hundred days that year. An Alberni newspaper put it bluntly: “Kennedy Lake, those people who are about to be written right off, are now seeing the light: there is no tunnel at all and thus only their end is in sight.”31

A Fine Balance

I had an interesting conversation during this time, at a “meet and greet” gathering at one of my new places of employment. One woman, upon learning my husband worked as a mechanic for MacMillan Bloedel, said of the War in the Woods, “I don’t understand why you people take it so personally!” I explained that although I saw the bigger picture, it did affect me personally, because my husband would soon be losing his job, and we and many of our friends and family members would quite possibly have to leave the town we loved. I further explained that a small number of people had expressed hatred for all loggers, which again felt personal, since I come from a logging background. The day my non-confrontational husband, who usually worked in the camp shop, came home from work to describe having been spat on by a protestor, it felt personal. (He could have so easily opened the truck door and that guy would have gone off the bridge and into the water. I thought my husband showed great restraint.)

I look back on my past as a member of a logging family and think of the losses. My brother was killed in a logging accident while taking time off from university to work in the woods. One of my uncles died in a logging accident, leaving my aunt with three little daughters. A close friend died in a logging truck accident. My roots go deep, and some of the memories are painful. I also remember the good times, the years growing up in Kennedy Camp, the sense of community of living in Ucluelet. It is a fine balance, and much of it is personal.

I, like so many others, saw the need for change in logging practices. I saw there had been some changes, that more were coming and that change wasn’t happening fast enough. I understood the passion the protestors had for the environment. Many loggers also care about the environment.

It was the black-and-white way of looking at things I didn’t agree with, the “all logging is bad and all loggers are evil” attitudes that were, and still are, sometimes expressed. I have always seen the grey areas. The woman I spoke with saw black and white.

What Next?

It became clear that MacMillan Bloedel was pulling out of the area; unemployed loggers and their families weighed their options. By January 31, 1997, when the closure of Kennedy Lake Division was official, there were just forty-four jobs left. All the other workers had been terminated or had taken voluntary severance. The focus became “What next?”

Future Prospects

With funding from Forest Renewal BC, a training facility was set up in the former Whale’s Tale restaurant in the heart of town. My husband, Keith, joined other former Kennedy Lake Division employees to plan for the future. We wives attended several group sessions at the Whale’s Tale Skill Centre. I recall sitting in a room where we had previously dined with friends on special occasions, and wondering how many more ways I could serve Kraft Dinner to my family. The irony did not escape me.

The Skill Centre encouraged self-employment, especially for those hoping to remain in Ucluelet. My husband had seen the writing on the wall for quite some time and chose to train as a computer technician and open his own business in Ucluelet. At age fifty, he moved to Victoria for the better part of a year to attend college, came home and set up shop in the basement. (How did that work out? With the business plus several part-time jobs, he kept the wolf from the door, but it was a struggle… It turns out if you are the kind of person who doesn’t always charge people for services, it’s hard to make a living. I pointed out to him once that we, like the people he was undercharging or not charging at all, were also having a hard time, but that didn’t register. Once a nice guy, always a nice guy.)

Other unemployed loggers opened businesses. Mickey Ralston ran a small appliance repair business. Ted Eeftink took on the local PetroCan franchise. Some ex-loggers found seasonal jobs in the burgeoning tourism industry. Many were forced to sell their homes and relocate, some of them finding jobs elsewhere in the logging industry. It was a changed town.

Joint Venture

First Nations on the coast had been understandably frustrated about their lack of say and input in ongoing discussions around logging. George Watts was a leader of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, which includes numerous nations whose Traditional Territories lie within Clayoquot Sound. He put it succinctly, describing it as distressing to “see these people who stole our land now divvying it up and fighting about it.”32

In 1998, a joint-venture logging company called Iisaak Forest Resources Ltd. was formed. At that time, it was 51 percent owned by MaMook Natural Resources, a partnership of five Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations: Ahousaht, Hesquiaht, Tla-o-qui-aht, Toquaht and Ucluelet. The other 49 percent was owned by Weyerhaeuser (which had bought out MacMillan Bloedel). Iisaak means “respect” in the Nuu-chah-nulth language, and the plan was to work towards respectful, conservation-based forestry practices. Iisaak was to provide joint management of the natural resources of Clayoquot Sound until treaty negotiations were completed. The two groups confirmed their commitments to work towards achieving change.

In 2001, Iisaak became the first forestry company in BC to be certified by the Forest Stewardship Council. In 2005, they bought out Weyerhaeuser. In 2007, after Iisaak purchased TFL 54 (a tree farm licence granting timber harvesting rights in an area of Clayoquot Sound) from Interfor, they became the first 100 percent First Nations–owned forestry company.33

In June 2024, a newspaper headline proclaimed: “War in the woods battlegrounds will be preserved.” The article described the establishment of ten new conservancies in areas including old-growth forests and unique ecosystems. Representing the Ahousaht First Nation, Tyson Atleo said, “We will see [Tree Farm Licence 54] on Meares Island actively become real legislated protected areas for the first time in history.”34

Barkley Community Forest

Few loggers reside in and around Ucluelet today. Those who do mainly work because of the Barkley Community Forest Limited Partnership, which is jointly owned by the Toquaht Nation and the District of Ucluelet. Barkley Community Forest Corporation was incorporated in 2011. It operates under a volunteer board of directors, and contracts out to a general contractor and other staff. Logging contractors are expected to adhere to Barkley Community Forest’s high standards.

When this partnership was formed, Ucluelet’s then mayor, Dianne St. Jacques, enthused: “This has been a dream that we have envisioned for more than a decade.”35 Anne Mack, Chief of the Toquaht Nation, agreed, stating: “I’m looking forward to the opportunities that the new community forest will provide to our community.” She cited more power over land management, as well as increased economic and employment opportunities.36 The previous Chief, Anne Mack’s father, Bert Mack, spent many years laying the groundwork for the joint venture.37

The sustainable logging brings needed funds into both communities. Former Ucluelet mayor Mayco Noel described the partnership as “one way we’ve been able to maintain our forestry roots, even though we’ve diversified our economy by focusing on tourism.”38