Chapter 11: Life-saving Boats and Coast Guard

It took a major tragedy to bring lifeboat stations to the west coast of Vancouver Island. For years, the Dominion government and the insurance company Lloyd’s of London had an agreement to provide aid to the island’s west coast in the event of marine disasters. The salvage steamer

Salvor was always kept at full steam, ready to deliver lifeboats when needed. But the Salvor was based in the calm waters of

Esquimalt Harbour, far from the treacherous Graveyard of the Pacific. In January 1906, when the passenger ship Valencia ran aground north of Carmanah Point, at least 117 passengers and crew died. None of the women and children were among the thirty-eight survivors. The inquiry following the tragedy recommended, among other things, that lifeboat stations be established along the west coast at Pachena, Ucluelet and Tofino. The Pachena Bay station was soon moved to the more protected waters of

Bamfield Inlet.

The first lifeboat station at Ucluelet was located at Hitacu. It was moved across the bay to Spring Cove in 1908, under the charge of well-known Ucluelet resident August Lyche. In January 1908, marine agent Captain James Gaudin visited the coast to try and hire more crew for the lifeboat, but he was unsuccessful because the pay he offered was deemed inadequate. Crew members manned the lifeboat with oars and sails, routinely risking life and limb in horrific weather conditions. Something at least akin to a living wage would have been welcomed.

When there were not enough paid crew, volunteers stepped in. One such event was big news in the Victoria Times Colonist of October 18, 1911. The launch Ucluelet, owned by the West Coast Fishing and Curing Company, left Toquart, and Herbert Hillier noticed it had not arrived in Ucluelet. Alarmed by a rising storm, he sought volunteers to man the lifeboat, meeting with “a ready response” from settlers and the First Nations community. Former coxswain August Lyche led the crew, and they “struck out in the teeth of the gale,” rowing eight kilometres before finding the launch struggling in breakers. They threw a line to the two men in the Ucluelet, and with Tom Tugwell as captain and Ted Thornton (probably meaning Ed Thornton, brother of Wilfred Thornton) as engineer, they rowed for three hours of “hard pulling,” towing the launch to safety in Barkley Sound. The men in the launch decided to shelter there with their boat. The eleven lifeboat volunteers then made the eleven-kilometre “hard pull back home,” where they were met with coffee and other refreshments.

The article commended Herbert Hillier for identifying and dealing with the potential disaster. Both the Ucluelet and Toquart telegraph offices were acknowledged for staying open to assist the rescue.

In February 1912, tragedy struck during lifeboat-crew training in Barkley Sound. The crew, now under the leadership of coxswain William Thompson, was attempting to land for lunch on one of the Double Islands (later renamed Chrow Islands around 1936), about five kilometres northwest of Ucluelet. The boat was swamped. None of the nine crew wore lifebelts. The Victoria Daily Times of February 19, 1912, reported: “The accident was wholly unexpected as the crew had on previous occasions made similar landings under worse weather conditions.”1

The crew was unable to right the craft, and most of them swam for shore. Twenty-four-year-old Thorval Wingen had been struck on the head when the boat went over. Coxswain Thompson tried to tow him to land, but the ordeal “sapped the strength of the plucky lifesaver” and the strong surf pulled Wingen from his grasp.2 Others tried to help but were thrown against the rocks. Thorval Wingen from Tofino had been a crew member for several years. He was a strong swimmer, and it was felt he would have survived had he not been knocked unconscious.

The rest of the crew, some of them injured, returned overland to the Ucluelet life-saving station.3 The SS Newington was sent from Victoria after the accident. The crew recovered Thorval’s body the following day and took it to Clayoquot for burial on Morpheus Island.

At a public meeting in Ucluelet in September 1912, H.S. Clements, MP, presented Thompson with an engraved watch in recognition of his heroic attempt to save Thorval Wingen.

Trading Oars for Gasoline

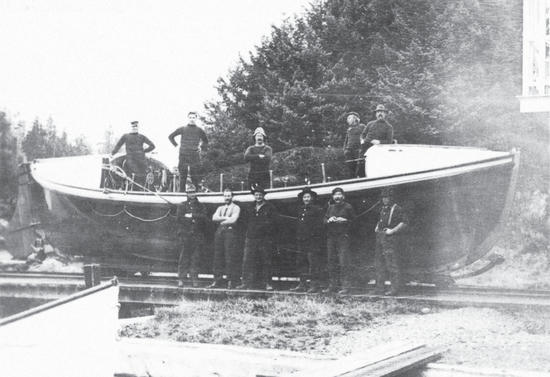

The year 1913 brought welcome news. Under the headline “Lifeboat for Ucluelet,” the Province newspaper reported that “members of the Ucluelet life-saving station…are to receive a handsome Christmas present this year…The husky men who now pull the Ucluelet lifeboat are looking forward with eagerness to the time when they will no longer have to use their long oars, but will be able to listen to the music made by the chugging of the gasoline engine. At Ucluelet is one of the most powerful crews that ever stepped into a lifeboat.”4

The lifeboat, launched in Vancouver in late December 1913, was the first of its type built in Canada. The Bamfield lifeboat had been imported from New York. Ucluelet’s new lifeboat, built by V.M. Dafoe and Co. of Vancouver, was a “self-righting, self-bailing, centre board gasoline engine, 35 to 40 horsepower vessel, 36 feet long, 8.10-foot beam, 5 feet deep and fitted with oars and sails.”5 Built of Honduras mahogany and oak, she had brass and copper fittings.

The new craft was deemed “unsinkable,” having six watertight compartments containing one hundred copper air tanks. The motor was encased in a watertight compartment. In acknowledgement of wild West Coast seas, the boat was fitted with life straps “to strap the captain and engineer to their posts when necessary.”6

The boat was to travel to Ucluelet under her own power, first stopping at Victoria for outfitting. After a nine-hour crossing from Vancouver to Victoria at three-quarter speed, plans changed. On January 6, 1914, she was hoisted aboard the lighthouse tender CGSEstevan and delivered to Ucluelet. Ucluelet’s previous lifeboat was transferred to Clayoquot. The surf boat from Clayoquot went to Clo-oose.

In 1915, the Ucluelet lifeboat went a hundred kilometres offshore to rescue the American powered fishing schooner Puritan, which had lost her propeller and was “wallowing helplessly in a bad sea,” taking on water and drifting seaward. The Daily Colonist reported this was the first call out for the Ucluelet lifeboat in several months, and that she “reached the disabled ship in the shortest possible space of time.”7

In 1918, the 1908 problem of manning the Ucluelet lifeboat recurred. Marine Department officials explained that “every able-bodied man within a radius of many miles of the west coast station has abandoned his former pursuits to engage in the more remunerative business of fishing.”8

The Victoria Times stated there were between 200 and 250 boats of all types, mainly under power, engaged in fishing out of Ucluelet. “The fishermen were making as much in a day as the lifeboat-men were drawing down in a month.”9

In July 1918, the Ucluelet lifeboat station was closed down. Some blamed financial cutbacks caused by World War I. Others believed it was due to lack of a crew because of inadequate wages. James Fraser was hired as caretaker of the empty lifeboat station.

Ucluelet then relied on the lifeboat stations at Bamfield and Tofino, which still served the west coast. Commercial fishermen and other Ucluelet and area mariners continued to aid in emergencies at sea.

Given the dangerous marine environment, there was public outcry. In 1955, the Port Alberni chamber of commerce called for the establishment of a Canadian Coast Guard service on Vancouver Island’s west coast. A petition was already being circulated along the coast, urging the establishment of services similar to those of the US Coast Guard.

Canadian Coast Guard

The Marine branch of the Department of Marine and Fisheries was founded in 1867. It was officially named the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) in 1962. From then until 1995, the CCG operated under the Department of Transport. In 1995, the federal government announced another change, and the CCG now operates as an agency within the Department of Fisheries and Oceans. The CCG, as a special operating agency, has a fair amount of autonomy. Its headquarters are in Ottawa.

The period from the 1960s to the 1980s saw a need for expansion of the CCG, due to a huge increase in marine traffic. Ucluelet’s strategic location on the Graveyard of the Pacific, and at the entrance to Barkley Sound, inspired big changes for the community. In February 1976, the CCG advertised for tenders for a Vessel Traffic Management system.10 An operations building was constructed on a Coast Guard site at Amphitrite Point, overlooking the lighthouse and the open sea.

Part of the system was a three-storey, radome-topped building atop Mount Ozzard. Many refer to this iconic structure as the “golf ball.” (Sometimes locals, when feeling overwhelmed by tourists, have suggested they try “the revolving restaurant on top of the mountain across the bay.” All in good fun, of course.)

The radar installation on Mount Ozzard had two generators, referred to by Vessel Traffic Management staff as “Henry” and “Shirley.”

The new system used the call sign “Tofino Traffic,” considered easier to pronounce and understand than “Amphitrite Traffic” or “Ucluelet Traffic.” When, in April 1980, the Coast Guard marine radio station relocated from Tofino to the new centre at Amphitrite, the historic message continued to be “Tofino radio, Tofino radio,” as broadcasted from Tofino Airport since 1956.

The creation of the Amphitrite Point Vessel Traffic Management Centre brought an influx of new residents to Ucluelet. Radar and radio operators and maintenance staff arrived with their families, boosting the economy, buoying up the school population, and increasing the number of community volunteers. Sandy Henry arrived with his family in early January 1978, one of the initial group of eight staff members, with Dave McMillan the officer in charge. The centre officially opened on January 2, 1978. After several months of preliminary work and on-site training, the group commenced watch keeping on March 6. The next group of eight arrived, and rotating eight-hour shifts of two-man watches were set up.

The technology could scan ships within a hundred-kilometre radius. This was especially crucial during impenetrable fog and challenging seas. Sandy Henry said the system “worked like a charm most of the time” with the American, British, and Canadian ships going up and down the coast.11 Problems arose when foreign vessels had no English speakers on board. The Vessel Management staff spoke slowly and clearly but could not always get their messages across to the foreign vessel crews.

One close call was when a Chinese cargo ship called the Daisy was observed heading straight for the rocks of Amphitrite Point. Sandy later said the ship, “as far as we could tell, navigated across the North Pacific with a road atlas.” Urgent warnings were radioed repeatedly by Ray Henri, but apparently not understood, for the ship stayed on her course to destruction, and all warnings were responded to with a polite “Thank you.” Finally, someone who understood English acknowledged the calls and changed course, at that point just one and a half kilometres from the rocks. Further instructions were radioed as the ship headed towards reefs inside Barkley Sound. At the last minute, the ship again altered course, and the Amphitrite staff “wiped the perspiration off their brows.”12 That type of incident happened several times. “It kept you on your toes,” Sandy said.

Monitoring marine safety had its stressful moments, but there were also sources of entertainment for staff at Amphitrite. Sandy recalled watching grey whales hanging out off the point, rubbing against the red can-buoy anchor chain to rid themselves of barnacles.

He described his twenty years at the Vessel Traffic Management Centre as a watch supervisor as interesting and at times “kind of tense.” During fishing season, there would be upwards of eight hundred trollers “all over the place.” They tended to congregate in clumps wherever the fishing hot spot was. If the large vessels did spot the trollers, the result could be quite disconcerting, as at night strobe lights flashing on trollers would “drive a deck officer nuts trying to avoid them.” It was easy to provide advance warning and steer the ships with English-speaking crew around these clumps of trollers. Difficulties persisted when watch staff couldn’t communicate with some foreign vessels.

On July 22, 1991, the Chinese deep-sea freighter Tuo Hai struck the Tenyo Maru, a Japanese fish-processing ship. They collided in fog, west of the entrance to Juan de Fuca Strait, where the factory ship was buying hake from Canadian fishboats. The Tenyo Maru sank, and eighty-four people were rescued from the water, and one man lost. The staff at Amphitrite saw the impending collision on radar but could not bridge the communication gap with the non-English-speaking vessel crew.

The environment and wildlife were further casualties. As many as ten thousand seabirds were predicted to die because of the massive oil leakage from the sinking ship. Vulnerable marine mammals were also possible victims.

In 2014, the Amphitrite Point Vessel Traffic Management Centre was closed down. The decision was contentious. The concern about maritime disasters along our coast does not focus only on loss of life and loss of ships. There is also constant worry about the possibility of an oil tanker disaster and the catastrophic damage it would cause along the coast. Coupled with issues of marine safety was the economic and social impact on Ucluelet.

The closure was seen by many as an ill-advised budget-cutting strategy of the Conservative government. The facility had reported marine weather conditions, identified vessels entering Canadian waters and received and relayed distress signals. After the closure, all calls once handled by Ucluelet went to a Prince Rupert site. On April 22, the day after the Ucluelet facility closed, the Prince Rupert facility lost power in the middle of the night, leaving no coverage for distress signals along the treacherous west coast of Vancouver Island. Coast Guard vessels started monitoring emergency channels, but it was a disconcerting start to the new system.

Another possible reason for the facility closure was the huge decrease in the number of trollers and fish-factory vessels offshore, which were once a major part of the navigational picture monitored by radar.

The initial installation atop Mount Ozzard was a low-frequency radar with an eight-and-a-half-metre reflector. The radar dated from the end of World War II, and was not disturbed by rain, fog or snow. It was replaced with a nine-gig navigational radar, susceptible to interference from inclement weather. This fits with the overall Canadian system, rather than being uniquely suited to the West Coast.

In 1995, the Canada Shipping Act was amended with the establishment of the marine environmental protection plan. Concern from both citizens and government entities about our area of the West Coast led the Western Canada Marine Response Corporation to build an oil-spill response base in Ucluelet, and the bright orange, blue and white response vessels were seen coming and going from the harbour on marine training exercises. This did not completely alleviate concern about the risks of increased tanker traffic when the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion project went through in 2024.

The Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary

This not-for-profit group has existed since 1978. In 2012, the name was changed to Royal Canadian Marine Search and Rescue (RCMSAR), but their mission to save lives on the water remains the same. Ucluelet’s Station No. 38 is one of fifteen stations making up the Central Region of the RCMSAR. The volunteers are on call twenty-four hours a day, year-round.

Initially, the Coast Guard Auxiliary was made up entirely of owner-operator boats. A local society was formed, and they raised funds to buy a boat and build a boathouse. The group still functions with owner-operators, but there is also a dedicated fast-response boat housed in a shed at the outer boat basin.

Becoming an RCMSAR volunteer requires marine experience and a pleasure-craft operator card. Volunteers joining the crew are provided with unit and regional training, including certification in first aid and marine VHF operation.

Brian Congdon, long-time volunteer with the RCMSAR, has been out on many search-and-rescue missions, often on his seaworthy Dixie IV, a former lifeboat. On one memorable occasion, Brian and a crew of two were called out by the Coast Guard to assist a boat heading up from the States. It had lost power and missed the entrance to Juan de Fuca Strait. Brian described it as “the kind of night nobody should be out in.” By the time they found the struggling boat, winds had picked up from storm level to hurricane force, and the boats were thirteen kilometres offshore. Using his knowledge of local reefs and rocks, Brian guided the two boats safely into Ucluelet Harbour. In the wild seas, he lost the Zodiac dinghy he was towing. The Bamfield lifeboat crew stayed overnight in Ucluelet and found Brian’s Zodiac the next day, on their trip home to Bamfield. David Hagstrom, officer in charge of Bamfield Coast Guard, presented Brian with 180 metres of nice tow rope for future rescues.

Mark Livingstone, a highly regarded RCMSAR volunteer, lost his life in a tragic industrial accident in 2007. Mark worked as a Canadian Coast Guard radio operator and dedicated many hours to volunteering on search-and-rescue missions, fundraising and hands-on work, such as building the boathouse for the dedicated marine vessel. A plaque on the boathouse honours his contributions. Mark was very focused on marine safety, and in his memory, the longest leg in the Van Isle 360, a sailing race circumnavigating Vancouver Island, was named the “Mark Livingstone Leg.”