Chapter 20: Answering the Call

Charles Mclean was the first medical doctor in the Ucluelet area. He arrived in the early 1900s with his wife, Sarah, and children, settling in a house built for them on the Hitacu reserve. Dr. Mclean delivered granddaughter Sheila to his daughter, Sarah Thompson. Sheila (whose surname became Mead-Miller) later said she sometimes travelled with her grandfather on his rounds, waiting outside homes while he tended to the inhabitants. Her grandfather didn’t want her exposed to common contagious illnesses of the time, like tuberculosis. Dr. Mclean covered a wide area, hiking rough trails, beaches and headlands, and rowing up to the head of Ucluelet Inlet. He sometimes rowed or sailed across treacherous waters as far as Cape Beale Lighthouse.

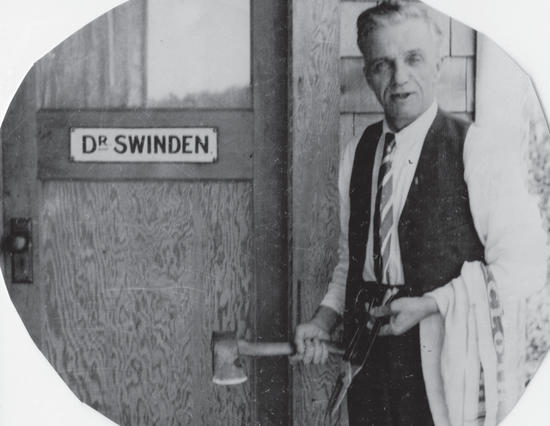

After Dr. Mclean retired to Victoria in the early 1920s, Ucluelet had intermittent doctors, including Lily Kvarno’s brother Dr. Guy Palmer, Dr. Bavis from Port Renfrew, Dr. D.C. McDevitt and Dr. Swinden.

West coast residents needing hospital care were usually transported by steamship. The Princess Maquinna had a nurse aboard, and stewards provided seasick passengers with buckets when needed.

During World War II, the Ucluelet base had a doctor who would see to civilians, but priority went to members of the forces. Sheila Mead-Miller recalled going into labour before she had time to go to Port Alberni. The doctor at the base was called, and arrived with a younger visiting doctor in tow, one who was nervous and “didn’t know too much about ladies.” When they got there, son Michael had already been born, with the assistance of his father Ken. When the older doctor didn’t sterilize the scissors to cut the cord, the younger doctor glared disapprovingly. Sheila said the younger doctor came back later with a sulfa pill, thinking “maybe that would offset the damage. I got a great kick out of that.”1

The government wharf was a common site of injuries. When Margaret Thompson was nine, she fell off the wharf; her brother D’Arcy called down to her, “Don’t drop your new fishing line!” Someone dove in, retrieved Margaret and drove her to the seaplane base. After dealing with three pilots (also soaking wet, having crashed their plane in the harbour), the doctor attended to Margaret’s broken collarbone.

In 1947, Frank Hillier fell off the wharf while riding his bike. He said, “I tried to fly,” but he hit the fender block below. Dr. Monteith set Frank’s broken arm at Tofino Hospital, took X-rays and sent them out of town. They came back with the official evaluation that Dr. Monteith had done “the best he could.” The bones healed well.

When Roger Gudbranson, at age ten, fell off the government wharf and broke his arm, there was no doctor around, so he was flown by float plane to Port Alberni for medical attention. Roger recalled that on the follow-up flight to have the cast removed, the plane skimmed low over the water below dense fog. The doctor used what looked like a Skilsaw to cut off the cast. “He only nicked me once,” said Roger.2

When Reggie Johnson accidentally drove a pickup truck off the Whiskey Dock, he went straight to the bottom and kicked a window out to escape. Dr. McDiarmid escorted him up the wharf to the clinic.

In the early days, dentists were scarcer than doctors. During World War II, locals were often able to go to the air force dentist stationed at Long Beach, who stated: “I always take anybody from Ucluelet or Tofino if they are in any kind of emergency.” He wanted to save them trips to Port Alberni: “I’ve been seasick so many times on that trip myself, they have all my sympathy.”3

At times, Ucluelet actively campaigned to attract a resident dentist. They advertised at North American dental colleges, hoping a newly graduated dentist might settle on the west coast.

When I was a child, there was a visiting dentist. I don’t recall his name. I do vividly recall the huge needles and the horrific smell, noise and vibration of the drill. My mother was dubious about this particular dentist from the get-go. He had very shaky hands. When he stuck a needle right through a child’s cheek, my mom said to my dad, “That’s it! We are taking the kids to a dentist out of town!”

Residents Step Up

When there was no available doctor, women of Ucluelet took charge of health care. Some of them had previously worked as nurses.

Annie Parkin, proprietor of the Vogue Style Shop, freely offered her nursing services as needed. Most of her collection of 175 cups and saucers was given to her as thanks for such help. Annie was regularly called to Hitacu for assistance, and given fish and crafts in appreciation. One stormy evening, she was needed in Port Albion and Pete Hillier took her across by boat. Annie fell overboard. Annie’s grandson Gordon recalled: “Pete hauled her out by her left arm thereby saving her life but breaking her arm. After she caught her breath (and no doubt straightened her hat as she was never without one!), she said, ‘Well, let’s get on with it, Pete, I don’t use my left arm much anyway.’”4

The Parkins’ home sometimes served as a makeshift mortuary. Annie told her grandchildren stories “of people passing away, being brought to the house and put on the dining table to be washed before being taken to wherever they went from there. She spoke of one evening she had a fellow on the table in the dining room and there was a knock on the door. A young airman was looking for help as his wife had injured herself. Grandma asked him in while she got her coat and hat from the closet. When she came out, he said, ‘Mrs. Parkin, there is someone lying on your table.’ Grandma replied, ‘Oh, he’s dead, don’t worry about him.’ She said, ‘The silly boy just slid down the wall in a dead faint, I had to wake him up before I could go help his wife.’”5

Agnes Tugwell was a former registered nurse who often provided health care to her own family as well as other Ucluelet residents. When eight-year-old Emmie May Binns was severely injured, her family quickly called for help from the neighbouring “Mrs. Tug.” The Binns family had a barrel of water which was pumped up from their well, then heated by the cookstove. The kids called the barrel “Big.” It was atop a large box. Emmie had sat on the corner of the box and bumped the bung (plug) out of the barrel. Both her legs had been badly scalded. Agnes Tugwell poured carron oil on Emmie’s legs and wrapped them in cloths, returning every day to add more oil.6 “I was in bed on a sort of frame father Binns made,” Emmie stated. “This went on for weeks.” Then “Mrs. Tug came and told me she was going to unwrap my legs, and every day she came with tweezers and lifted off bits of the old skin—took a long time. But never left a scar on either leg.”7

Emmie also recounted that years later Pat Thompson was very ill with double pneumonia. Emmie sat with her each day, and Agnes Tugwell sat with her each night, putting mustard poultices on her. “It was life or death,” Emmie wrote, adding: “Pat lived.”8

Many other Ucluelet residents provided health care as needed over the years, including RNs such as Ruth Wadden, and my mother Chris Baird, who volunteered with the public health nurse, Myrt Saxton.

Tofino Hospitals

In 1934, Dr. John Robertson came to Tofino and spearheaded the building of a hospital on land donated by Roland Brinkman and Captain Alex Macleod. The provincial government covered 40 percent of the cost. The local communities went into high gear, determined to raise the needed 60 percent.

Members of the Ladies’ Hospital Aid put on dances, bazaars, bake sales and raffles. They also sewed up a storm, creating bed linens, curtains and other needed items for the hospital-to-be. At a fundraiser vaudeville show, one of the more dramatic events of the evening was Dr. Robertson’s trapeze act—he hit a rafter and broke a rib.

The necessary funds were raised, and the hospital was built by dedicated volunteers. A Port Alberni mill donated a scow load of lumber. The local ladies served huge lunches to the labourers, who took only a few months to finish the building. To fit the budget, the new facility was heated by wood stoves, had a coal-fired kitchen range, and was lit by Coleman lamps. By 1936, the two-storey hospital was operational.

The early patients paid a dollar a day and had to bring their own “nurse,” usually a family member. The Ladies’ Hospital Aid continued fundraising, while doing some cleaning and cooking in the hospital. Dr. Robertson’s wife, Marguerite, assisted her husband with operations he performed on a table he had built himself. Before long, the hospital had not only a doctor, but three nurses, with a residence provided for them nearby.

The eighteen-bed Tofino Hospital was well used by residents of Tofino, Ucluelet and surrounding areas, until disaster struck. On Sunday, May 11, 1952, the hospital caught fire. The news soon reached St. Columba Church, where the service abruptly halted as everyone rushed to the scene.

Delegates attending a Masonic Lodge meeting joined the volunteer firefighters in rescuing patients from the burning building. The Ucluelet Volunteer Fire Brigade arrived over the rough gravel road in a record thirty-five minutes to assist. Limited water supply hampered efforts to extinguish the fire. Some records and medical equipment were saved, but the building was destroyed in under two hours.

Six patients, including an expectant mother, and a mother and newborn, escaped unharmed. Victor Kimola, in his book Long Beach Knights, describes his mother’s escape: “She burst out of the building and into the early morning of fresh air and firemen bravely battling the blaze without hesitation, until they spotted a small smoldering pregnant woman amongst their midst.”9 Victor’s soon-to-be father, a Tofino volunteer fireman, “was astonished to see his short Scottish wife emerging from Dante’s inferno,” and said to her, “Good God…what are you doing in this burning building?”

Margaret replied, “That’s what I would like to know,” before being whisked away to safety, and giving birth to her third son, Victor.

The nurses’ residence was commandeered as a makeshift hospital, and a surplus building was donated for temporary use.

The New Hospital

Fundraising began again in earnest. But first, Ucluelet and Tofino vied to be the site of the new hospital. At the time, Ucluelet had a larger population. However, Tofino had more outlying First Nations communities, giving it the larger overall population to be served. When a Ucluelet committee argued it would be more affordable to renovate an old RCAF building in Ucluelet, then health minister Eric Martin responded that Ucluelet could have its own hospital if it met “all necessary pre-construction requirements.”10 Meanwhile, the government would proceed with the construction of a new hospital in Tofino.

Land for the site was donated by the Garrard and Monks families. The Ladies’ Hospital Aid carried on with bazaars, bake sales and dances. A fashion show held in Ucluelet was a large draw, with burly males donning showy getups, including two-piece bathing suits and lingerie. The ever-supportive Padre Leighton was one of the models.

When there was a shortfall of funds, many locals put up their homes, and in some cases their boats, as loan collateral. The target amount was reached by the deadline. The new Tofino Hospital officially opened on August 12, 1954, with over a thousand people gathered at the grand opening. Health Minister Eric Martin acknowledged the “remarkable community spirit,” stating: “This can certainly be claimed a people’s hospital.”11

When Dr. Gordon Fyffe, resident doctor at the new hospital, left, Dr. Howard McDiarmid took over, also providing office hours in Ucluelet and Tofino. After several years, Dr. Wheeldon came in to assist him.

A residence was provided to encourage nurses to come to the area. Nurse Vaida Siga recalled an influx of newly trained nurses from Ontario in the 1970s. There were no screens on the windows, and when Vaida was on-shift she would sometimes hear the young nurses screaming, “Vaida, they’ve done it again!” Some local kids liked to “welcome” the new nurses by throwing snakes through the windows. The nurses would cover Vaida’s shift while she cleared their rooms of snakes.

Over the years, many dedicated doctors have served Tofino, Ucluelet and surrounding areas, including Dr. Fast, Dr. Henderson, Dr. Killins, Dr. Foulkes, Dr. O’Brien and Dr. Frazee.

Many babies were born at Tofino General Hospital over the years, including my own. (My first daughter was delivered by a locum from Vancouver, my second by a doctor/fisherman who lived on an island off Tofino.) Vaida Siga recalled that every full moon brought excitement, with up to three women in labour at the same time. I, like so many other new mothers, had not only expert doctor care, but the skilled support of nurses like Midori Matley, Phoebe Jensen and others. Many west coast babies were named Midori after that lovely lady.

In 1989, Tofino Hospital opened a new birth room, created with funds donated by several Tofino and Ucluelet businesses and individuals. At that time, then hospital administrator Frank Van Eynde estimated that between forty-five and fifty babies were delivered each year at the hospital.

In 2007, Tofino Hospital cancelled its obstetrics program, citing a declining number of local births and a critical nursing shortage. At the writing of this book, expectant mothers have to go elsewhere for their deliveries.

In 2018, a welcome banner was unveiled to celebrate a traditional First Nations cleansing ceremony. The hospital was given a Nuu-chah-nulth name, Šaaḥyitsapaquwił, meaning “a place where people go to get well.”12

Ucluelet Medical Centre

In the early days, visiting doctors saw patients in a rented room with a kerosene heater in the corner, on the main floor of Binns’ Barn. Paper-thin walls meant there was no such thing as privacy. When it came to medical conditions, nothing was sacred—the set-up was somewhat akin to the “party line” telephone system.

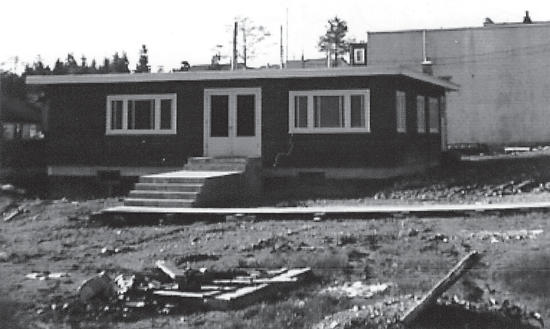

Ucluelet’s present District Office, the Lyche Building, was a project of the Ucluelet Centennial Committee, for the 1958 centennial. The group received a grant of approximately $500, as the population of Ucluelet was 499 at the time. With costs projected to be at least $15,000, fundraising and donations were a necessity. The Ucluelet Centennial Committee consisted of individuals from many Ucluelet non-profit groups.

The building was constructed with volunteer labour, under the capable direction of paid project foreman Walter Huser. Someone was always running to Phil Thornton’s hardware store for more nails. Ann Branscombe recalls her brother-in-law Johnny Gerbrandt coming home from driving school bus, going straight over to the building and pounding nails until dark.

The building was used for years as a medical and dental centre. Dedicated public health nurses Myrt Saxton, Donna Turner and Vaida Siga provided public health care from that building. The structure was later expanded to include a public library. The Village of Ucluelet had the use of one long room and was in charge of collecting rent from the doctors, public-health and dentist programs. As the rent increased, they had to move out, with the Village gradually taking over the building.

The medical offices moved from place to place, including what was originally Ruth Hillier’s apartment next to Ruth’s Gift Shop, and the building now housing Blackberry Cove Marketplace. The clinic presently in the complex near the credit union will soon move to a new facility on the outskirts of town.

The Cemetery

The Sutton brothers donated land for Ucluelet Cemetery. A Mr. Williams, who lived nearby, suggested a cemetery there, and was the first one to be buried there. Phyllis Binns described going to her uncle George Binns’s burial as a child, at which “the funeral procession was an adventure in itself.” The coffin was taken up the inlet by boat to await the arrival of the town’s one ox, “which had been coaxed along the mile-and-a-half corduroy road between the village and the head of the bay.” The remains were then loaded onto a type of sled called a stone boat, which the ox hauled up a three-kilometre rough trail to the graveyard. “It seemed to us such a lonely place to leave poor Uncle George,” Phyllis stated. Now, of course, Ucluelet Cemetery is not only easily reached by car but has many more residents.

George Jackson, an early Long Beach homesteader and telegraph lineman, probably has the most unique plot in the cemetery. He wanted to be buried upright. After George’s death in 1930, his friends drank to the deceased with beer he had provided. Then they blasted a deep vertical hole with dynamite. George was interred, as requested, in an upright position.

The ground at the cemetery got very soggy in the rain. Ken Gibson described one interment where there was so much water that his father told the minister to “cut out the glory part and speed things up.” Halfway through the service, the coffin floated, then flipped over. “Reverend Leighton just kept on reading from the good book.”

The Nameplate Project

Over the years, many simple wooden crosses disintegrated in the weather. There were about forty unmarked graves in Ucluelet Cemetery. Talia Corlazzoli and Matteo Ludlow decided to “recognize, respect and honour the people that used to live in our community.”13 The teenage cousins, guided by District employee Wanda McAvoy, went through old records to find death dates of the deceased. With the help of Talia’s father, Dario, they created forty cement crosses, using gravel donated by Dave Ennis. They then glued nameplates, paid for by the Clayoquot Biosphere Trust, onto the crosses. In 2019, the two caring teens completed their project after three years of work.

Education

In the early 1900s, Alice Lyche started teaching three or four students in the living room of her home. When there were nine students, a school (with outhouses) was built where the Lyche Building now stands. Sheila Mead-Miller related that several local settlers took children from an orphanage into their homes to bring the attendance up to the required number. Eventually, a blanket divided the main room into two classrooms, one for Grades One to Four, and one for Grades Five to Eight. Those students wanting to carry on with their schooling did so through correspondence or boarded out in Port Alberni or beyond.

Settlers gathered to make needed improvements. In 1911, “a stumping bee was held at the Ucluelet school house to clear the ground in order to make a playground for the children. The settlement turned out in full force and spent a very enjoyable day.”14

Sheila Mead-Miller described Alice Lyche as “a tremendously good teacher. It was good she was here, the children needed her, but she could have done so much in the world.”15 Students from across the bay rowed over daily in a large canoe. Mrs. Mead-Miller recalled rowing herself up the harbour to school when she was nine years old and lived at Spring Cove.

Pete Hillier enthused that his early teacher was the “only woman I’ve ever seen that could rock in a rocking chair and read at the same time,” adding that she used to correct the students’ grammar, “but never in front of their friends.”16

Stapleby School

In 1911, when many newcomers settled at the head of the inlet in Stapleby, it was quite a hike to Ucluelet, especially for children. A school was built at the corner of what is now the Pacific Rim Highway and the Willowbrae Trail. The one-room school opened in around 1914, serving students from Grades One to Eight. For a time, it had a higher enrollment than the school in Ucluelet proper.

Many of the children walked for kilometres along boardwalks to the school. Once there, they did chores, including cleaning the blackboard, sweeping the floor and chopping kindling for the wood stove. They also drew water with a bucket on a rope, from a very deep well. My aunt Mary Baird (née Karn) recalled, “As kids we used to drop a rock in and hear it drop.”17 The school had an outside privy, and there was no school janitor.

Aunt Mary said some of the teachers were very strict. As was common in those days, the strap was used daily, so she kept her eyes on her books to stay out of trouble. The organ at Stapleby School was put to good use when the students entertained their families with concerts.

Eventually, the number of pupils in Stapleby School dropped. George Grant tried to keep the school open, several times advertising for a new teacher, with the prerequisite that the teacher would also provide students: “Wanted—Male teacher with children of school age, for Ucluelet Arm School. Apply G.W. Grant, secretary, Stapleby P.O. BC.”18

When the school closed a few years after the war because of dwindling enrollment, the remaining students went by boat to the school at Ucluelet East, later called Port Albion.

Ucluelet’s Two-Room School

With an influx of Japanese Canadian families, the settlement of Ucluelet needed a larger school to house all the children. The board of education supplied some materials. Money was donated by locals, including the Japanese Canadian Society. The Shimizu brothers, skilled boatbuilders and carpenters, oversaw the project. The new two-room school stood on the site of the present-day District Office. Japanese Canadian fishermen helped build the school, which was completed in the fall of 1925. For many years, Mrs. Clark taught the lower grades, and Mr. Noble the older ones. In 1928, there were thirty students, many of them Japanese Canadians.

In 1944, there were approximately twenty pupils in the Ucluelet School, and the teacher taught Grades One to Seven for a yearly salary of $1,100. In February 1945, a teacher was urgently sought through an ad: “Apply by night or day letter, stating salary required and qualifications.”19 Terry Smith recalled that Skeet Haines, a bounty hunter, used the big old deciduous trees outside the school to hang cougars on after he’d shot them, making for an atypical school playground.

Hitacu Day School

Although some of the Hitacu children were sent away to schools such as the Alberni Residential School, many of them attended the day school started by the early Presbyterian missionaries. Teachers usually resided at the school. The original building was eventually replaced by a Quonset hut.

Olwen Watt, a young teacher from Wales, had a brief stint teaching in Ontario’s snowy north before returning to her home country. In 1958, a friend told Olwen about a job on Canada’s West Coast and she applied. Upon arrival in Vancouver, she learned there was no road to her new home. At Port Alberni, she boarded a float plane bound for Ucluelet. Olwen said that “to get on the plane was quite a chore,”20 with her legs confined by the pencil skirt of her stylish suit. Her luggage was left behind, to be sent on later.

Arriving at the government wharf in Ucluelet, Olwen was met by Charlie McCarthy in his fishboat. He took her “way across the water”21 to the Hitacu reserve and up a path to the school. There, a teacher from Toronto named Mary Hoskin was all packed up, ready to leave. Olwen didn’t feel ready to take charge of the school, so Mary stayed on. Olwen and Mary taught fifty-one Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ students that year, grouped in two separate classes. The students attended up to age fifteen.

The two teachers shared a room above the school. There was an outside privy and no running water. Charlie McCarthy’s daughter Edith welcomed Olwen and they became lifelong friends. Eventually, Olwen and Mary moved across to Ucluelet, finding accommodation with running water. Lawrence Ives transported them back and forth daily to the school on his fishboat.

Olwen first met her husband, Bill, one rainy day when he arrived at the door of the Quonset hut to deliver something. She and Mary invited him in. “Oh no,” he said, “I’ve got to get cleaned up first.” He soon returned, with a book of poetry tucked under one arm.

Bill had arrived in Ucluelet in 1946 aboard the Maquinna to visit a friend for a week or two. He fell in love with the area and stayed on. Bill drove logging truck for Saunders, later dispatching logging trucks for MacMillan and Bloedel. Olwen, originally a home-economics teacher, took on that role at Ucluelet High School when she and Bill were married. Soon after she left the school at the reserve, it closed down, and in 1964 the students began attending school in Ucluelet, transported across the water by Charlie McCarthy’s son Alec in his boat the Jalna.

Olwen later taught at Ucluelet Elementary School. My daughters both benefited from her gentle guidance and lovely lilting voice during their kindergarten years.

Port Albion School

The Port Albion school, also known as Ucluelet East school, was situated on Sutton Road. Over the years, there were ongoing struggles to keep this school open. In the early days, the Whipp family enrolled their five-year-old daughter to make up the necessary number so the school wouldn’t close. Efforts focused on a registration of fifteen students, although regular attendance was considerably smaller.

In 1923, the teacher at Ucluelet East school was paid $1,000 per year, with partially furnished accommodation available for six dollars a month. A janitor cleaned, and the teacher was responsible for keeping the wood stove going. Despite the school’s forested locale, firewood was described as “difficult to obtain.”22 C. Winfield Matheson, the teacher in 1923, expressed concern about the children’s safety: “A one-plank sidewalk is the way over which the children have to come to school and return. This is really dangerous as they are always liable to fall off and injure themselves. The government should attend to this at once.”23

By 1928, the salary had increased by twenty dollars a month.

When the Bridal family arrived in Port Albion in 1944, their six children boosted the student population. Lloyd Bridal recalled the first teacher as “an older no-nonsense lady,” adding: “I don’t know if she retired or we all drove her crazy.”24 He described the next teacher, Miss Pitt, as “a beautiful young gal with long dark hair,” who was “overall…a lot of fun.” On one occasion, Miss Pitt and Margaret Doiron decided to ride down Doiron’s Hill in wheelbarrows pushed by Lloyd and his brother Chuck. En route, they encountered sixty-five-year-old Albert Jacobs heading up the hill. “Instantly, he threw his barrow into the ditch and jumped into the ditch as well and let us go roaring by. He said he never saw the like in his life.”25

Lloyd recalled that Miss Pitt could easily be talked into taking the students for walks in the woods, which they all enjoyed. The kids also brought nature into the classroom. One morning, Lloyd found a tiny owl in an apple tree and carried it to school. “I put it on front of my desk and it sat there blinking all morning. Needless to say, not very many were paying attention to the teacher that morning.”26 The kids returned the owl to the apple tree branch on their way home for lunch.

By 1955 the teacher at Port Albion school was provided with a fully furnished teacherage, with rent described as “moderate.”27

Port Albion children attended that school from Grades One to Six, then travelled across the bay aboard Alec McCarthy’s Jalna to attend school in Ucluelet. The boat was crowded with students from both Hitacu and Port Albion. The youngest kids had to sit out on the stern, as the cabin wouldn’t hold all the kids. This resulted in Dave Taron being given the nickname “Poopdeck.”

A New School for Ucluelet

As the population slowly rose, plans were made for a larger building. In 1952, a school was built on the site of the present Ucluelet Secondary School. The property, purchased from the Ucluelet Athletic Club (UAC) for one dollar, was part of the land previously donated by George Fraser to the UAC. Volunteers helped clear the land, pushing all the stumps to the back into burn piles. John Gerbrandt hooked a plane propeller up to his V8 flatbed, and the resultant fanning of air sped up the burning process.

The new school had three classrooms, an industrial-arts room and a gym. Until it was completed, industrial-arts classes were held in St. Aidan’s Church basement. The Ucluelet Elementary Junior Senior High School housed all grades, as well as a school board office. It had its own generator for lights and heat, since local power was not consistently reliable. There was no buzzer to indicate class changes; “changing subjects meant changing books instead of classrooms.”28

In the summer of 1952, a city newspaper advertised for a high school teacher for Ucluelet, emphasizing a “5-room modern school.”29 In September, the search was still on, with a teacher “wanted immediately.”30

The hiring process was challenging. Isolated Ucluelet was not a popular draw for teachers. Those who came were often in their first year of teaching, and would soon leave for somewhere nearer civilization. Teachers frequently taught outside their specialty field, or taught age groups they weren’t trained for. It was many years before Ucluelet became a desired destination.

The first Ucluelet High School graduating class celebrated in 1954, having attended the new school only for their Grade Twelve year.

The present elementary school was built in 1954, with renovations and additions taking place over the years. The high school then served Grades Eight to Twelve from both Ucluelet and Tofino. The small building between the elementary school and high school was once the local School District 79 office. The small building also housed kindergarten classes for some years. It later became a base for the school maintenance workers.

Earlier kindergarten classes were held in the basement of the Catholic church. The teacher was a lovely lady named Marge Renneman. I know I enjoyed kindergarten, but my main memories are of sugar cookies, juice, a story and a nap on a roll-out mat on the floor. We were only there for half-days, so I am unsure why we needed a nap; I suspect it was more for Mrs. Renneman’s sake than for ours. We were a lively bunch.

I attended Ucluelet Elementary and Ucluelet Secondary from Grade One to Twelve, and also worked in the schools for twenty-three years, so I naturally have many memories. One dramatic event took place in March 1966. During our Grade Ten science class, we got an unexpected lesson in meteorology. Shakes from the adjacent UAC Hall roof crashed through the windows as we dove under our desks to escape flying shards of glass. A twister had hit Ucluelet!

The shrieking spiral, accompanied by thunder and lightning, cut a swath about 120 metres wide and 300 metres long through the centre of town, leaving around $100,000 of damage to property.31 The twister broke pilings, smashed docks, lifted roofs and blew the Nitsui family’s two-car garage a hundred metres into the harbour, then swept it a further two hundred metres out the bay. Amazingly, no one was hurt, despite a three-hundred-kilo timber crashing into the UAC Hall, and a fifteen-centimetre metal spike flying into the typing classroom to lodge in the blackboard. All in all, it was the liveliest day we students ever experienced during class time.

That event meant many window replacements for the schools. Since then, Ucluelet Secondary School has undergone at least four renovations. In 2020, a huge project was in the works after the schools were deemed a seismic risk. Major renovations took place at the elementary school. At the end of summer 2022, a large portion of the old high school was razed and replaced by a structurally sound school of modern design. Apparently, when seen from the air it is shaped like a fish.

The Ucluelet area once had its own school district, which in 1952 was enlarged to include Tofino. The Ucluelet schools, along with Tofino, Long Beach and Port Albion schools, made up School District 79. They had their own secretary-treasurer and trustees, but shared a superintendent with Parksville-Qualicum.

In 1969, District 79 amalgamated with the Port Alberni area as part of a larger school district. In 2020, the district’s name was changed to SD 70 Pacific Rim. At that time, they put feelers out about changing the name of Ucluelet Secondary School, as it serves not only Ucluelet but also Tofino and other outlying areas. The answer was a resounding no, and Ucluelet Secondary School it remains.

Police

The first policing of the area was done by Gus Cox, who became a special constable to the BC Provincial Police in 1892, and chief constable for the West Coast District in 1904.32 Constable Cox was based in Alberni but well equipped to cover the west coast, having grown up at Cape Beale, where his father was lightkeeper.

The first resident policeman in Ucluelet was early settler John Kvarno. The police station, including jail, was attached to his home. Despite the small population, John’s policeman role kept him busy. The Victoria Daily Colonist reported a story in August 1907 relating to the tragic sinking of the Valencia, a ship driven onto the rocks near Pachena during a violent storm. A man named Abraham Handgrif had been washed off a small raft while trying to escape the wreck and drowned, becoming one of the estimated 117 victims. Constable Kvarno later retrieved Handgrif’s body from the sea, and his remains were interred at Wreck Bay. Subsequently, the body was exhumed and taken to Victoria aboard the steamer Tees.

Court proceedings were usually dealt with by residents who were designated justices of the peace. An article in the Daily Colonist on December 19, 1900, refers to proceedings as handled by the designated justices: “The legal tribunals on the west coast of the island have no plush-covered dais on which sit the leather-bound chairs of the justices, nor are there brilliant lions and unicorns painted on the walls. Court is usually held in the village store, or, failing that, the missionary house, which is usually the most pretentious in the settlement.” The article continues with a case overseen in Ucluelet by presiding justices James R. Sutton and A.H. Lyche, with court held in the village store and the local missionary acting as counsel.

One BC Provincial policeman posted to Ucluelet lived in a small house where Davison Plaza is now situated. An ingenious sort, he drilled two holes through his bedroom wall and extended string through the holes to his chicken coop behind the house. When the rooster crowed each morning, the constable pulled one string to dispense water and one to dispense feed. “Thus the chickens were fed and watered without the constable getting out of bed.”33 Next to the constable’s house was a small building used as a jail cell. The house would later become the home of the Parkin family, and the former jail cell became Mrs. Parkin’s Vogue Style Shop.

Although the official birthdate of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (originally called the North-West Mounted Police) is May 23, 1873, the RCMP did not take on provincial policing contracts in British Columbia until August 1950.

When Ucluelet was a small and isolated community accessible only by boat, the police were often involved in at-sea rescue attempts. In March 1946, Ucluelet constable George Redhead, along with Dick Whittington of Long Beach, attempted to rescue five navy men swept into the sea from their capsized cutter. Four of the sailors were rescued, but Whittington drowned in the process. Constable Redhead narrowly escaped death, clinging to rocks until rescued.

The number of criminal incidents rose over the years, after the road went through and the number of visitors increased. Long weekends at Long Beach required extra policing, when swarms of visitors arrived to camp. On the May long weekend of 1973, a group of inebriated young out-of-towners set a camper truck on fire on crowded Long Beach, and aimed it, engine running, towards the ocean—the flaming truck swerved before reaching the water and headed directly for a group gathered around a campfire up the beach. Ucluelet constable Van Warmer threw a log in front of the blazing vehicle, stopping it before it reached the group. Nine Port Alberni youths were arrested at the scene. Corporal Stewart of the Ucluelet RCMP reported that despite the influx of over ten thousand people at the time, trouble was caused by “an idiot minority,” and most of the crowd was well behaved.34

The present police station on Cedar Road is on the site of the previous one, a solid brick building which also included a two-storey house for the sergeant and family. When the station was torn down in 1986, there was a public outcry, as many locals felt it would have been the ideal building to house the library, which needed a better location.

With the brick building demolished, a temporary structure was bought from John Gerbrandt to house the police station. It was then purchased and relocated by Dave Manuel, and a new building was constructed on the site.

An auxiliary RCMP group was formed, with volunteers including Ron Burley, Brian Pilon and Roger Gudbranson. Roger recalled that during his thirty-five years with the group, the most hectic patrol times were during herring season, with its influx of fishermen keen to celebrate a successful catch, and during May long weekends, when Long Beach was inundated with lively campers.

The Ucluelet Volunteer Fire Brigade

My husband, Keith, volunteered on the Fire Brigade for thirty years. We saw many changes over that period. In the early 1970s, we were in a mall in Victoria, and Keith was wearing his Fire Brigade jacket. Two men walking by did a double-take, and one said to the other, “Ucluelet Fire Brigade! Two guys and a bucket!” Keith and I had a laugh over that, but also knew the brigade did so much more. It has a long and proud history of community commitment and volunteerism.

The Ucluelet Volunteer Fire Brigade held its first official meeting in December 1949. Back then, the town was much smaller and most of the houses were close to the water. There was a large pump and hose stored at the Standard Oil building dock. That hose could reach most of the houses and boats. In those days, most fires were wood-stove related, or boat fires.

In 1950, a spectacular blaze lit up the sky when boiling tar ignited, setting a big dock shed full of fishing supplies afire. The Ucluelet Volunteer Fire Brigade rushed across the bay to Ucluelet East with their equipment, saving not only the wharf but an at-risk troller on the nearby ways.

Ucluelet’s growth called for more equipment. The first pumper truck, a ’52 Ford one-ton water tanker, was acquired in 1952. It had only 105 miles on it when it was sold seven years later and replaced by a 1928 Graham pumper truck, for a cost of $2,300.

The fire hall consisted of a shed on Peninsula Road, across the street from Mr. Parkin’s shoe store. Roger Gudbranson stopped there on his way to his father’s automotive garage after school each day, to check that the batteries for the ’52 Ford truck were charging and had water in them.

The brigade needed a more substantial building. In 1952, the Ucluelet Athletic Club provided land adjacent to their hall, and the Ucluelet Volunteer Fire Brigade started the five-year lease on November 7, at a cost of one dollar a year. The UAC later sold the property to the brigade for $500.

George Gudbranson was one of the founding members of the brigade and the first fire chief. When Jim Morgan, a former firefighter, interviewed George in 1999, on the brigade’s fiftieth anniversary, George recalled that when there was a fire call, they would all hear one long ring on the phone, since everyone in town was on the same line back then. As phone lines improved, several people had fire phones, and when a fire call came in, they would dash to set off the siren. For many years, Lorne White had the fire phone in his home.

By 1960, it was clear a new fire hall was needed. The village and the brigade made a deal—the brigade would supply the bricks and the Village would supply the labour to build the hall. Of course, the brigade made up much of the Village and vice versa. Brigade funds paid for a cement mixer and moulds to make the bricks. This was time-consuming work, so John Gerbrandt, with helpers George and Roger Gudbranson, drove his flatbed truck out to Port Alberni to pick up concrete blocks bought in Beaver Creek. Roger recalled it as a very bumpy ride. With store-bought blocks, the hall was built in short order by Joe Skoda and volunteers.

Over the years, Michael Mead-Miller served as captain, assistant chief, chief and local assistant fire commissioner. Mike recalled that one of the most spectacular fires was when a hangar at the former seaplane base burned down. The building was filled with road-building equipment, and the fire was caused by an exploding acetylene torch. Everything inside the hangar was destroyed, and the siding on the Transpacific Fish building next door buckled from the heat.35

When Mike retired, he convinced my husband to take over as chief, a position Keith held for seventeen years. As the community grew, Keith saw the need for a paid fire-chief position and resigned as fire chief in 2009 to emphasize that need. Deputy Chief Jarrod Oye then kept things running until, with Keith’s encouragement, Ted Eeftink became fire chief, serving in the role with dedication and focus for eleven years. Under his leadership, the Ucluelet Volunteer Fire Brigade took on rigorous formal training to meet new National Fire Protection Association standards.

Ted continued to lobby for a full-time paid fire chief. On May 13, 2019, Chief Rick Geddes took on that position. The Westerly News reported the hiring as “a significant step in the progression of services provided by the District of Ucluelet.”36 Chief Geddes’s role includes overseeing Ucluelet’s emergency management program.

In 2020, the Ucluelet Volunteer Fire Brigade transitioned to the name Ucluelet Fire Rescue, reflecting their municipal status and an increase in rescue calls. In 2023, Markus McRurie was hired as deputy chief. Long-time brigade volunteer Mark Fortune continued in his deputy chief capacity.

A volunteer crew of firefighters continues to devote time and energy to the cause. It is impossible to list the names of all the volunteers over the years, but I would like to respectfully acknowledge two fine young firefighters, lost too soon. Sandy Henry Jr. died in a tragic industrial accident in 2002. Shawn England passed away from cancer in 2010. Sandy and Shawn were dedicated volunteers and esteemed role models.