Chapter 7: The Names on the Cairn

The early settlers were a hardy and adventurous lot, drawn to the West Coast in a quest for fur, gold, fish, lumber and land. They came from across Canada, the US, Europe and Asia. To survive and thrive in Ucluelet and the surrounding area would require courage, ingenuity, hard work, resilience and tenacity.

A concrete cairn stands in front of the Ucluelet District Office. It provides the base for a bronze plaque:

"B.C. Centennial A.D.

Erected to Ucluelet Settlers prior to 1900

"

The plaque lists the names of many of those who settled in Ucluelet before the twentieth century.

Will and James Sutton

The Sutton brothers were born of an interesting line. Their grandfather, Richard Sutton of Sedbergh, England, is said to have inspired the character Heathcliff in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights.

The move to Ucluelet was their father William Sr.’s idea—having come to BC from Ontario, he was on the lookout for marketable resources. By early 1891, Will and James had settled on the east side of Ucluelet Harbour at a site now called Port Albion. There, they acquired timber leases and built log cabins, a sawmill and a store on the government dock. The 1891 census shows the occupation of both brothers as loggers, but Will focused on running the sawmill.

Will and James were keen phrenologists. Phrenology, which was popular during the Victorian era, is a racist pseudo-science involving the detailed study of the size and shape of the human skull, supposedly to identify character traits and mental abilities. Phrenologists also collected skulls. Will and James began robbing First Nation graves, selling the remains to phrenologists in the US. Through this abhorrent enterprise, they connected with Franz Boas, the so-called “father of American anthropology,” and managed to send him assorted skeletons and crania, “making in all one hundred and twenty-three individuals.” The remains were shipped “invoiced with a falsified origin and labelled as natural history specimens.”1

As a further sad note, in a letter to Franz Boas dated January 8, 1891, James wrote: “As we are now moving out to the West Coast of Vancouver Island it is very likely that we may make a large collection…If we should do so we will notify you to that effect.”2 However, there does not appear to be any further record of contact between Boas and the brothers, and no evidence that they robbed graves after moving to Ucluelet. Sutton descendant Jan Bridget writes in her book about Will and James: “The racism shown in their actions reflects the principles of colonialism.”3

Will moved back to Victoria in 1892, having married Helen Annie Fox, originally from England. In 1895, the couple moved to Houghton, Michigan, where Will taught at the Michigan State School of Mines.4

Will and Annie returned to Victoria around 1899, and he worked as personal geologist for industrialist and politician James Dunsmuir, inspecting mining sites across BC and beyond. Annie occasionally accompanied him, sometimes on horseback. Will frequently travelled to Ucluelet. His West Coast interests included lumber, hydro power, placer gold mining and promotion of the area.

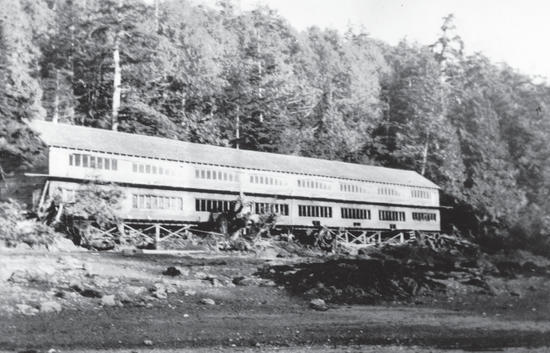

The Sutton Lumber and Trading Company, officially formed by William Sr. and his sons in 1893, was a family venture. James ran the general store at Port Albion. Will managed the sawmill, called the Ucluelet Mercantile Company Sawmill.

In a 1903 talk in Victoria, Will described challenges facing those trying to extricate a living from the wilderness. He recounted his struggle to reach Wreck Bay through the bush: “The sallal was so thick that I had to roll over it, instead of forcing through it…I rolled down to Wreck Bay, and when I reached the Lost Shoe Creek I had to ford it.”5 (Will lost a shoe to the current while fording the creek, hence the creek’s name.) He then “made a pair of moccasins by tearing off a piece of my trousers” and hiked the beach, struggled in the dark through the bush along Ucluelet Arm to his canoe, then paddled more than a kilometre back to camp against a headwind.6

While never downplaying its harsh landscape, Will enthusiastically promoted the west coast of Vancouver Island. He helped form the Vancouver Island Development League, encouraging settlers to move to the Ucluelet area. Will recommended building more trails and a road for west coast access. His passion for opening up the area extended to May 9, 1914. A dispatch wired to Victoria from Ucluelet stated: “Mr. W. J. Sutton dropped dead at 9 o’clock this morning, while running a survey line for a road in process of construction.”7

Unlike his brother, James Edward Sutton resided for many years at Ucluelet East. He married Ada Belle Walters in San Francisco in March 1891, and brought her back to his two-room cabin. James delivered their first child. When the family increased by three, James built a larger house on the hill behind the dock. Tragedy was narrowly avoided on Christmas Eve of 1898 when the house burned to the ground. James was away in Alberni. Ada woke all four children and guided them safely from the burning building. Compounding the stress, neither house nor contents were insured. James then built a third house, this one on the site of the burned-down house.

Ada was a spiritualist, and in the 1901 census James listed his religion as the same. Spiritualism is a system of belief based on supposed communication with the dead and evolution of spirits in the afterlife, and it was quite popular at the time. Jan Bridget theorized that Ada’s beliefs helped end James’s grave-robbing activities.8

James and Ada remained in Ucluelet East for almost twelve years. The Sutton store was an essential hub of the small community and also housed the post office. James traded with the local First Nations and learned their language. In 1896, he was made justice of the peace for the Cowichan–Alberni district and presided over disputes between the First Nations and the settlers and traders. He was noted for fair decisions, often ruling in favour of the First Nations.

In 1902, James, Ada and family moved to California, having sold their Ucluelet holdings. James died in 1935, aged seventy-two. Ada was seventy-seven when she died in 1946.

John Margetish

Augustus James Margetish was born in Austria in 1842. Although known by the Christian name John, he was often called “Frenchie.”

John married the widow Elisa Lucky, née McFadden, in Victoria in August 1887. Her first husband, George Lucky, had been a sealer and master mariner, captain of the schooner Anna Beck. Unluckily, he had died at the age of forty-four, after only six wedded years, leaving his widow with three children.

In marrying John Margetish, Elisa chose another man of the sea. John went sealing in the Bering Sea, worked along the coast as a sailor and general trader, and by 1894 was managing Captain Spring’s store at Spring Cove.

John “Frenchie” Margetish died on April 3, 1898. Margetish family legend has it that, while walking home to Spring Cove that night, John came upon two men fighting over gold and witnessed one killing the other. His family believed he was seen and the murderer then did him in as well. John’s body was found floating in the sea.

At thirty-five, Elisa was once more a widow, left with seven (soon to be eight) children. She remained in Ucluelet for some years, running the trading post, before moving to Shawnigan and Victoria.

James McCarthy

One early settler who was in Ucluelet briefly but left a huge legacy was James McCarthy, often called “Red” for the colour of his hair. Said to have come from County Kerry, Ireland, he arrived in Ucluelet in the late 1800s to seek his fortune in the seal trade. James acquired huumanʔiš (Hyphocus Island) and lived aboard his boat, next to the island.

James met and married Susanna, the daughter of Chief Wickaninnish, a direct descendant of the powerful Tla-o-qui-aht Chief Wickaninnish of the late 1700s. James and Susanna had one child, born on July 17, 1895, a son they named Charles James.

Sadly, Susanna died when Charles was about four years old. Shortly afterwards, James gave up sealing and headed north to search for gold in the area around Eagle, Alaska. The order of what then happened to little Charles is unclear. Family believes that James arranged for his son to live for a time with elderly relatives. A family member told me they thought he went to Christie Residential School on Meares Island, since his father was Catholic and Charles was baptized there.

What happened to his father remained a mystery. Did James McCarthy perish in the North, and if not, where did he go?

James and Susanna’s son, Charles, settled at Hitacu. Records show that at the age of nineteen, he married eighteen-year-old Kathleen (Katy) Bob, daughter of Masitlawit and Nayeotl (Bob). They had a large family. Kathleen died aged thirty-five, from the after-effects of influenza. Charles remarried. His wife Della Mundy passed away at the age of thirty-nine, from tuberculosis.

While little is known of his father, Charles was a prominent West Coast individual. When he died in Lions Gate Hospital in North Vancouver in October 1966, a Victoria newspaper stated: “One of the most highly thought of Indian fishermen on the West Coast passed away this week in the person of Charles McCarthy…He was the grandson of Chief Wickaninnish.”9

Charles McCarthy is remembered as a hard-working and honourable man. He has many descendants, and the McCarthy name is well known at hitac̓u in the governance of the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ. Several of his descendants have served as elected Chiefs, and more of them have been Councillors.

John Kvarno

John Hartwick Kvarno arrived in Ucluelet aboard a sloop in 1895. He and his friend August Lyche were on a fishing expedition, liked what they saw, and settled here.

Kvarno (pronounced “Kwarno”) was born in 1867 in Namsos, Norway. The town sits on a small bay at the mouth of the river Namsen, one of the richest salmon rivers in Europe. Ucluelet must have reminded him of home.

John cleared property on the area that later became the seaplane base and established his farm. Working alongside him was his wife, Betsy Sudum, also originally from Norway.

John supplemented farming with fishing, and was Ucluelet’s first provincial constable. The police station was in their house. Betsy did dressmaking for local women. Just forty-nine when she died in 1921, she was interred in Ucluelet Cemetery. Helen, their only child, later died at that same age.

One of Kvarno’s many roles was as Ucluelet’s provincial election commissioner in 1926. That same year, Elizabeth Stewart came to Ucluelet and met the widower, whom she later described as a “good-looking Scandinavian woodman.”10 The attraction was mutual. John and Elizabeth wed on December 19, aged fifty-nine and fifty, respectively.

The full name of John’s new bride was Mary Ann Lily Elizabeth Stewart, and she often went by Lily. Lily brought considerable skill to the small community. Daughter of a certified midwife, as a teenager Lily had helped her mother in the profession, and went on to be certified in the same field. Lily delivered some 3,300 babies in her home country of England; on one memorable night, she delivered five babies in five hours. She once delivered triplets, a career highlight.11

With no hospital in Ucluelet, Lily was soon back at work. She assisted Dr. Guy Palmer, one of Ucluelet’s interim doctors. When he was away, she attended local mothers during childbirth. Decades later, on her ninety-ninth birthday, Lily recounted cherished memories of delivering babies for the local Japanese population in Ucluelet. Despite their uprooting during the Second World War, she still heard regularly from many of them, and was informed of “the many more babies that have been born into a second and now a third generation.”12

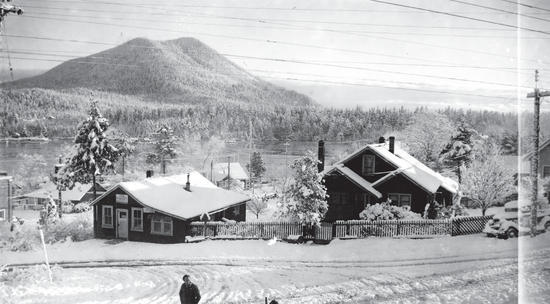

During World War II, John and Lily sold their property to the military for the seaplane base, replacing their life on a farm in isolated Ucluelet with a home and gardens in the city of Victoria. In 1944, four years after their move, John passed away in Royal Jubilee Hospital at the age of seventy-six.

By the age of 103, Lily was residing at Gorge Road Hospital, where one of the staff described her as “the sharpest little number you’ll ever see.” On her birthday, she was the last to leave the party, having cut the cake, signed thank-you notes and finished every bit of her tea. She passed away at the hospital in 1979, five months after turning 103.

The Kvarno name is commemorated by an island. Once called Staple or Stapleby Island, Kvarno Island sits near the head of Ucluelet Inlet, close to the residential area of Millstream on the inlet’s west side, and directly across from Thornton Creek Fish Hatchery on the east shore. In 2007, the thirty-hectare island was rezoned from “forest rural” to “small holdings.” It was then subdivided into fourteen large waterfront lots, with one shared lot in the centre of the island.

We were offered a chance to get in on the initial deal, and I was excited at the thought of having an “off-grid” getaway on this enchanting island near the end of the bay. My husband, however, begged to differ, stating he liked our little harbourside house “just fine, thank you very much,” and was a staunch fan of electricity, running water and indoor bathrooms. He also preferred not having to paddle to the Co-op every time we ran out of milk. But whenever I kayak around Kvarno Island, I sigh.

August Lyche

Although it has been written that no man is an island, many an island has been named for a man. In Ucluelet, not only an island but also a road and a building are named after August Lyche. In the centre of the harbour sits Lyche Island, once called Channel Island, and renamed in 1934.13 Lyche Road runs from Peninsula Road down past the boat basin to Waterfront Drive. The Lyche Building, circa 1959, stands at the bottom of Main Street on the site of Ucluelet’s first school.

August Herman Lyche was born in Drammen, Norway, on December 5, 1863. He came to BC in 1883 as a seaman on a ship that had sailed around Cape Horn. Conditions aboard the ship were brutal and the crew mutinied en route. Upon arrival in Victoria, the skipper had them arrested, but they laid countercharges, citing “cruelty and lack of nourishing rations.”14 The sailors won their case in marine court, and many of them stayed on in Victoria. August worked on several farms there until visiting Ucluelet with John Kvarno in 1895. Recognizing potential, August pre-empted a large block of land for his farm, in what is now the centre of Ucluelet. A versatile pioneer, August was coxswain on one of the first west coast lifeboats and was active in the fishing industry.

His wife, Alice Lee, had worked on her mother’s Victoria farm; she had a strong work ethic, and quickly settled into her new community. Ucluelet’s first schoolteacher, she held classes in her living room until a school was built. Sheila Mead-Miller commented that some people thought August and Alice an unlikely couple, in that she was highly educated and he was not. “But,” she added, “he was one of those kinds that educated himself, he had read a lot.”15 August helped with school-board record keeping and was a local justice of the peace. But as Mrs. Mead-Miller said, “Mr. Lyche’s idea of a vacation was to go out and clear land. He just loved clearing land.”16

August’s property was situated on Ucluelet Harbour, near present-day Cedar Road. He built a large house and continued to clear the land around it. Sheila Mead-Miller recounted: “He was going to blow some more stumps, with gunpowder, and it was cold in wintertime, and the gunpowder was cold, so he took it in and heated it on the kitchen stove, and he blew up the house.”17 Luckily, no one was injured. What was left of the house was torn down, and August proceeded to build a new home.

Continuing to clear land at some distance from the house, August was unaware that his bonfires had spread along roots underground. A fire broke out under the house—the second house burned down.

The third house became an iconic building in Ucluelet, and for years August and Alice ran it as a hotel called the Bayview Lodge.

After settling in Ucluelet with their two young children, Vera and Norman, August and Alice had a third, daughter Alma. Unfortunately, tragedy struck the family over the years: fourteen-year-old Vera died in Victoria in 1908. Their son Norman died at the age of thirty-two. He had earned a BSc degree at McGill University, and had taken up fishing for a living. On April 25, 1924, his gas boat, engine still running, was found aground just inside the harbour entrance. There was no sign of Norman. For two days, local fishermen dragged the harbour, with no success. August then offered a reward of fifty dollars for anyone finding his lost son.

An elderly Japanese couple named Kyuzo and Shima Shimizu made tofu to sell to local families. To cook the soybeans, they needed lots of firewood, which they regularly gathered at the head of the inlet. There, they discovered Norman Lyche’s body, which had drifted up the harbour. They quickly informed Norman’s father, who came for the sad task of identifying his son. Kyuzo then helped him take the body home, where he built his son’s coffin. When August later tried to give Kyuzo the fifty dollars, he declined, not wanting to accept a reward for such a tragic incident.

August Lyche continued to pour time and energy into Ucluelet and the surrounding area. He passed away in Port Alberni in 1939. His death shocked those who knew him, as he had gone to the West Coast General Hospital for what was thought to be a minor illness.

The Bayview continued to loom large on the landscape but was eventually divided up into rental suites. The building gradually deteriorated until it was deemed a fire hazard and torn down, ending the saga of the three consecutive houses built on that site by August Lyche.

Edwin Lee

Early settler Edwin “Ned” Lee contributed greatly to the community. Gold miner, fur trader, and general-store manager, he also served as Ucluelet’s postmaster and justice of the peace. Edwin (who was Alice Lyche’s brother) grew up in Victoria of hardy stock, which no doubt prepared him for the challenges of West Coast life.

In 1898, Ned, now twenty, contracted gold fever and set off for the west coast of the island. In 1901, back in Victoria, he married Bessie Marion Johnson, an English immigrant. The young couple departed for “Euclulet” aboard the Queen City, so Ned could pursue his work “in the development of the West Coast gold fields at Wreck Bay.”18

Ned worked the claim for three years. He sent a sample of gold-bearing black sand off to the Paris Exposition, and eventually received an ornate French certificate nearly two metres long, which he couldn’t read. He stated that was “about all he had to show for his mining venture.”19

For nine years, Ned and Bessie divided their time between Ucluelet and Victoria. With long journeys on often rough seas, this was a far more arduous commute than it is today. Their two eldest children, Weston and Bessie “Marion,” travelled with them. In 1910, the young family climbed aboard SS Tees for their permanent move to Ucluelet. Using lumber shipped from Alberni, Ned built a store with living quarters overhead, and a warehouse. By 1912, Lee’s General Store was open for business. In 1927, he built a stately two-storey house nearby.

Ned was a fur trader, one of four principal buyers on the west coast.20 Many purchases at his store were made with the barter system. The First Nations customers traded furs and dogfish oil for sundry items including tobacco, canned goods, gumboots, rifles, calico and that West Coast staple, hardtack (rock-hard biscuit rounds perfectly suited to sea voyage because they last forever). Business was brisk. Furs piled on the wooden counter included mink, bear, marten, otter, beaver and fur seal. The dogfish oil was carefully measured, with a nail exchanged for each gallon. First Nations people then returned the nails to purchase items, some of which were put on order to be delivered by boat from Victoria or Vancouver.

Like his sister and brother-in-law Alice and August Lyche, Ned and Bessie suffered a tragic loss. They celebrated the birth of their third child, son Edwin Powers Lee, in June 1913. One year later, twelve-year-old son Weston was out in a motorboat in the harbour with his fifteen-year-old cousin Alma Lyche. Weston was steering the boat when the tiller rope snapped, and he was thrown into the turbulent water. Alma bravely dove in and tried to reach him, but high wind and waves pushed her back. A rescue party was too late.

After four hours of searching in twelve metres of water, they retrieved his body. The Victoria Daily Times of July 6, 1914, reported that many friends attended his Victoria funeral, where the coffin was covered with flowers, including “a large wreath from the Ucluelet Arm and Ucluelet Sabbath school.”

Ned and Bessie’s daughter Marion moved to Victoria, where she became a teacher and married Vadim Stavrakov of Siberia. Son Edwin Powers Lee remained in Ucluelet, but declined taking over the family store, as he and his father did not always see eye to eye. Edwin married Minnie Edwards, daughter of Jonas Edwards, member of another long-time Ucluelet family. Minnie recounted to her granddaughter Theresa that as a child she lived out past the present-day bowling alley. Minnie ran swiftly back and forth to school each day on a trail through the woods, terrified by what might be lurking in the trees.

Since Edwin Jr. avoided the family business, Bessie’s nephew Vince Madden left his job clerking at a Clayoquot store to work at Lee’s General Store. He bought Ned’s business in the early 1940s, and Ned retired in Victoria, living on Lee Avenue next to the old family home.

Ned Lee died in Victoria in 1958, at the age of eighty, and was interred in Ross Bay Cemetery. His widow Bessie lived to be ninety-seven. Ned and Bessie Lee left a West Coast legacy, with Lee’s General Store, now the Crow’s Nest, still standing proudly in the heart of town, and Lee descendants carrying on the family line in Ucluelet.

Dr. Charles Mclean

Charles Mclean was the first medical doctor in Ucluelet and the surrounding area. He was born in Scotland in 1846, and married his wife Sarah Greig in 1879. While still in Scotland they had five children—three daughters and two sons. By the time they settled in Victoria around 1895, the family had crossed the Atlantic five times, because, as his granddaughter described it, Charles “had itchy feet. He’d been in the Navy and I guess he couldn’t stop.”21 In Victoria, an agent for the Department of Indian Affairs offered Charles a position as medical officer on the west coast. He convinced Sarah to uproot herself again, and they moved into a house built for them on the Hitacu reserve. Dr. Mclean provided medical care to the First Nations people, as well as to settlers of Port Albion, Ucluelet and outlying areas. He died in Victoria in 1930 at the age of eighty-four.

William Thompson

In the mid-1890s, William Lowell Thompson and his close friend Carl Binns left Ireland to seek their fortune. They worked their way across the Atlantic in a ship called the Lucipara, ending up in Ucluelet in 1896. William’s family members relate that he stepped ashore dapperly dressed in a foxtail coat and silk shirt.

William was “a short, stocky man with a strong work ethic…and possessed a true pioneering spirit.”22 His varied Ucluelet occupations included farmer, fisherman, telegraph operator, lifeboat captain, ship’s captain and hotel proprietor.

On May 5, 1903, William married Sarah Mclean, daughter of Dr. Charles Mclean. William and Sarah’s first child, daughter Sheila, was born at Ucluelet East in 1904, delivered by her maternal grandfather. She was said to be the first white child born on Vancouver Island’s west coast.

In 1907, when a lifeboat station was established at Ucluelet, William joined the crew as coxswain. By 1911, William was lighthouse keeper at Cape Beale. Another daughter, Eileen, was born there, and son Bud (Charles William Thompson) was born in 1913.

Upon leaving the Cape Beale Lighthouse, the Thompson family returned to Ucluelet. When World War I broke out, William signed up and moved his family to England for the duration of the war. His daughter Sheila later said, “Why we all went over, I don’t know. My father was Irish, and anything can happen with an Irishman.”23 William served aboard a British submarine in the North Sea.

After the war, William immediately brought his family back to his beloved West Coast and became lifeboat captain at the Spring Cove station. He also started fishing, but postwar recession set in. William looked elsewhere for income to support his family.

The American government had established Prohibition with the 1920 Volstead Act. This opened new employment opportunities, and William had the prerequisites—he was a seafaring man with a love of adventure. Thus began his profitable career as a rum-runner. His granddaughter Margaret, who was very proud of her enterprising grandfather, told me the cover name for his rum-running business was “Arctic Fur Trading.”

William’s son Bud went on a few of the rum-running trips as a teenager. William’s wife Sarah also made a trip or two. Margaret said she and her sister were shocked to hear that their devout, sweet little (five-foot-tall) grandmother disembarked with William in Mexico and entered a canteen. As a young woman, Sarah had been a teetotalling suffragette, with an attitude of “lips that have touched liquor will never touch mine.”24 That all changed when she met the dashing young William Thompson.

Despite his busy career at sea, William and Sarah also managed the Lyches’ Bayview Lodge for several years. Their daughter Sheila said her parents had a very relaxed attitude towards the enterprise. If it was a lovely day and there were no clients at the hotel, they would just shut it down and go off by boat for picnics. Her father would leave a note on the door: “We are away for the day. Come in and help yourselves. Play the record player and have something to eat if you can find it. We should be home this evening.”25 One time, they returned to find a note from a man named Billy Lord (who later became a well-known judge in Vancouver), saying he and two others had made themselves bacon and eggs and listened to the record player. The three men had cleaned up the dishes and left money. Sheila said her father’s way of doing business caused some people to think him “a bit of a nut…but it was fun. Nobody can say he wasn’t happy.”26

In 1931, after several years of running the hotel, the Thompsons gave it up because of Sarah’s arthritis. William returned to the sea.

That same year, William Thompson disappeared on a return voyage from Shanghai aboard the Chasina, a 235-tonne oil-fired steamer. The ship had cleared Macao on September 25, 1931, supposedly bound for Ensenada, Mexico. She was never seen again. Theories about her fate vary: Was there a fire, an explosion? Did she go down in a typhoon or other violent storm? Was she taken by pirates for her cargo, with the eleven crew members then murdered and the ship scuttled? To this day, the disappearance of William Thompson and his crew aboard the Chasina remains a mystery.

Before he left Ucluelet on that last voyage, William and his son Bud built a house along the road from Madden’s General Store, towards the present-day RCMP building. When her husband did not come home, Sarah moved into the house with Bud, his wife and their children for a while, then joined her siblings in Victoria. Sheila later said if her father had returned, he’d probably eventually “have taken off to Timbuktu.” He was a true adventurer, ensuring life with him held “never a dull moment!”27

There are many interesting stories to be told about William and Sarah’s three children and descendants, but this book cannot contain them all. I will restrict myself to just one, about their son. Bud was, like his father, an enterprising man. He was a commercial fisherman, owned a hotel and raised chickens on what is now called Hyphocus Island.

The island called huumanʔiš by the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ was given various names by settlers over the years, including Native Island and Maitland Island. It was pre-empted by Toichi Nitsui, and then taken from him during the internment of Japanese Canadians during World War II. The island was later owned by Winnifred Maitland, Bud Thompson’s godmother. She gave the island to Bud, and he decided to try his hand at chicken farming to supplement his fishing income.

His daughter Margaret said of her dad’s chicken farm, “It was a disaster.” He regularly added on to the second storey of the building with wood taken from the bottom—wood he meant to replace. The floor collapsed; some say this happened when a piercing whistle sounded from the Princess Maquinna as she rounded the point and the chickens went flying everywhere, with more than a few dozen eggs becoming scrambled. Margaret estimated he had about a thousand chickens at the time, and many of them took off for parts unknown. If that had been the only chicken farm mishap, Bud might have persevered. Unfortunately, the chickens he managed to round up contracted avian flu and had to be culled. That was the end of Bud’s foray into chicken farming. He sold the island, reportedly to pay off debts incurred while setting up the poultry business in the first place.

Carl Binns

Charles Carlyle Binns was born in Ireland in 1873 and grew up in a well-to-do family in Galway. A longing for change and adventure brought Carl to Ucluelet in 1895, alongside his close friend William Thompson (or “Willio,” as Carl called him). Carl, like William and the other early settlers, worked hard to make a living. Records of the day document his presence as a farmer, miner and storekeeper. Carl also transported mail from Ucluelet to Clayoquot and was on the crew of the Ucluelet lifeboat.

In 1901, the Daily Colonist reported: “At Uclulet things are becoming more prosperous since the development of the rich placers near by, and C.C. Binns, one of the storekeepers there, has about completed a wharf at which the steamer will tie up, instead of landing passengers and freight by boat as heretofore.”28

Carl spoke with a strong Irish brogue. It must have been interesting to hear him converse in the Chinook dialect, which he had soon mastered to communicate with the local First Nations people, who referred to him as “Codfish Charlie.”

On a return visit to Britain to see his sick mother, Carl found a wife in London-born Ethel Annie Brookes, a leather merchant. In 1905, Carl and Ethel married in Birkenhead, and by 1907 the young couple and their little girl Irene had emigrated to North America, settling in New York City.

There, two more daughters were born, Phyllis in 1908 and Emmie May in 1909. Carl supported his family by working as a waiter, a job he detested. He longed to leave Manhattan for the wild, open spaces of Ucluelet, and complained after long hours spent waiting tables at the posh Knickerbocker Restaurant that “every step on that marble floor’s polishing me own tombstone.”29

Carl returned to Ucluelet in 1913 with his wife and three young daughters. Waiting to greet them when the SS Tees tied up at the government wharf was Carl’s old friend “Willio” Thompson. William immediately offered Carl work on the lifeboat crew, and housed Carl and family in the Thompsons’ waterfront home. Ethel’s daughter Phyllis later shared that her mother felt as though she had “stepped off the edge of the world,” but took solace in the view of Mount Ozzard across the harbour.

Carl decided to build a home for his family, and chose property above the Main Street hill, near the site of the present-day Co-op store. He had grand plans, including a large living room, dining room and kitchen on the ground floor, with pantry and scullery, six bedrooms on the second floor, and four attic bedrooms. Ethel wanted a cozy cottage, but Carl persevered, eventually confiding he had an eye to the future, when Ucluelet would need a hotel.

Although Ethel worried the structure would turn out as grandiose as the mansions her husband was accustomed to in Ireland, it had box-like lines. Some locals said it was too high and narrow to be built on top of the hill and would blow over in a gale. Others commented on the size of the place; one was heard to say, “All those bedrooms! I can’t see why he has to build such a barn of a place!”30 The structure thereafter became known as Binns’ Barn.

The three Binns daughters loved their father’s “wild Paradise,” exploring the harbour, the beaches and the forest. Tragically, Irene died at the age of ten, having contracted diphtheria from a playmate. More family tragedy followed. Ethel passed away at the age of forty-one, from uremic poisoning, a complication of pregnancy. She was interred in Ucluelet Cemetery, next to Irene.

Carl ran Binns’ Barn as a rustic hotel, with his young daughters Phyllis and Emmie working alongside him. After two years, Carl decided it wasn’t viable and took on a job as lighthouse keeper at Amphitrite Point.

Carl continued to work hard on both land and at sea. He bought a boat called the Reliable (referred to by his daughters as “the Despicable”) to deliver supplies and passengers to logging camps and outposts along the coast. This new enterprise earned him the moniker Cap’n Binns. He lived aboard the Reliable, moored at the main dock in Port Alberni, and also in a float house in Alberni Canal. When Port Alberni port authorities removed his float house while he was away, an indignant Carl left aboard the Reliable to live up the coast. The 1935 voters list shows him as a prospector at Ahousaht, but he was actually based near there, at his Big Boy mine at Herbert Arm.

Carl Binns died in 1939 at the age of sixty-six from a virulent infection, after being flown by float plane from Tofino to Vancouver on what was described in the newspaper as a “heroic mercy flight.”31 Phyllis and Emmie accompanied him on the flight.

On the day of Carl’s funeral, a pickup truck drove along the narrow dirt road to Ucluelet Cemetery. Phyllis and husband Jack perched on the back to keep the coffin from sliding off as they toasted Carl with a bottle of rye. He was buried next to his wife and their daughter.

Phyllis and Emmie May were feisty and resourceful, having both worked from a young age to support their father’s endeavours after losing their older sister and their mother. Like their father, they had a variety of jobs, always keen to challenge themselves. They worked as telegraph operators and cannery girls, and assisted their father at his coastal mines. Eventually, Phyllis became a writer in Hollywood, and Emmie May honeymooned on the high seas as the wife of a renowned rum-runner. Phyllis returned to her West Coast roots when she settled at Long Beach with her second husband, Jack Martin.

George Binns

George Binns, Carl’s younger brother, was born in 1883, in Galway, Ireland. In 1911, he wed Ellen “Nell” Barrows, daughter of the governor of HM Prison in Belfast. The following year, George and Nell emigrated to Canada with their infant daughter Josephine, more often known as Jo.

When George fell terminally ill, he brought his wife and little girl to Ucluelet, and they moved in with Carl and family. In 1915, George passed away at the age of thirty-two, of tubercular meningitis, possibly caused by years spent working in coal mines.

George was interred in Ucluelet Cemetery. His occupation on his death certificate is shown with the intriguing comment “Attending Camps,” and his previous occupation as “Special police force.” Carl and Ethel continued to provide a home for Nell and little Jo, and for Nell and George’s baby girl, Patricia Ellen, who was born less than two weeks after George passed away.

Patricia Ellen would grow up to marry Charles William “Bud” Thompson, son of Carl Binns’s friend “Willio” Thompson. Carl and William, close friends since their early days in Galway, would have been thrilled to see their two families thus united.

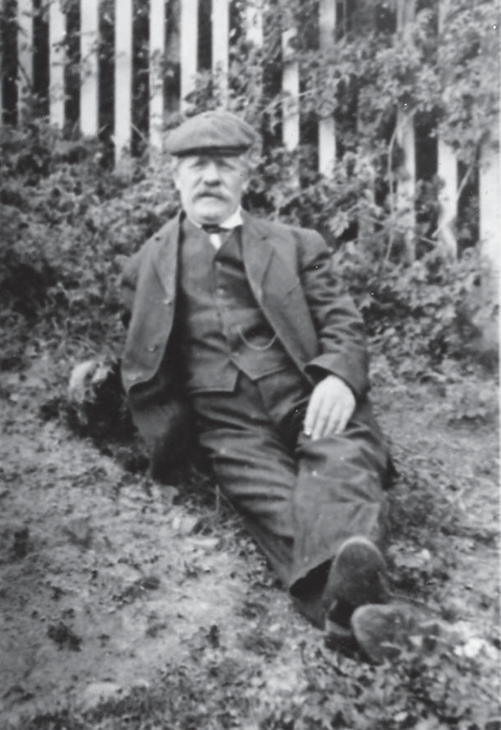

August Jansen

August Jansen (sometimes spelled “Janson”) was born in Sweden in January 1855. He emigrated to Canada in 1878, becoming a naturalized citizen in 1898. The 1891 census shows him residing in Victoria in a large household full of young male immigrants from countries around the world. From his Victoria base, August travelled up and down the coast, crewing on whaling and sealing ships, and by 1900 he had settled in Ucluelet.

August worked for the Suttons in their Port Albion store. The census of 1901 shows him as residing in their home. When James and Ada Sutton and family moved to the States, August took over the store. He was a “gentleman, short, thick set with blue eyes and fair hair, a sweet nature, good to everyone.”32 His kindness led him to offer credit liberally, which was not always good business sense.

The store housed a pot-bellied stove where men of the sea gathered “to talk and spit at it on cold nights. Seafaring tales ran wild from one to another.”33 An enterprising man, August bought salmon and cod from the local First Nations and smoked the fish in a big smokehouse behind the store. He sold cases of the smoked fish to customers in Victoria.

August had become a skilled cook while crewing on ships, and was known for his hotcakes, served with honey and thick cream. He relished eating cooked halibut heads, eyes and all.

The Johnsons, a couple from Scotland, helped run the Port Albion store, and took over management of it when August purchased a store at Spring Cove around 1921.

For a time, August owned the Shelter Islands. They were later renamed the George Fraser Islands, in honour of Ucluelet’s famed horticulturalist, but one is still called Janson Island. The islands are lovely, and locals back then picnicked there on calm days. But the fickle waters of Carolina Channel can boil and churn—August no doubt had some challenging trips transporting his goats and ox across the channel to Ucluelet Harbour.

August Jansen is last listed in the Ucluelet city directories of 1929 and 1930, still working as a storekeeper and postmaster. From there, he retired to Victoria, until he fell ill and moved to live with the Johnsons in Vancouver. He died there in 1935, at the age of seventy-nine.

Hitacu Elders Sarah Tutube and Gladys Sam used to paddle over to the Shelter Islands in the fall and pick fruit from the trees planted on those rugged islands years earlier by August Jansen.

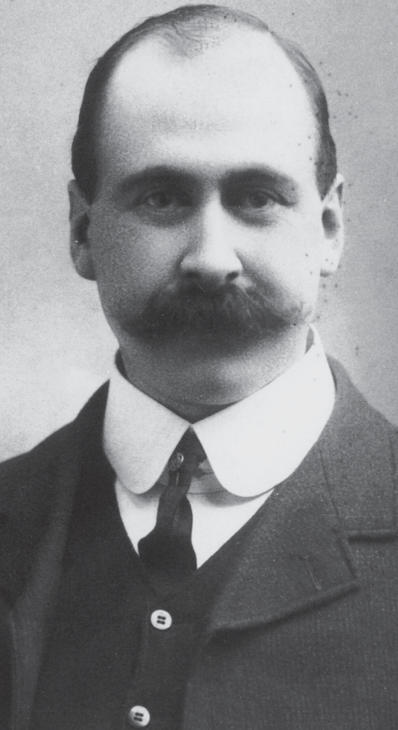

George Fraser

George Fraser, horticulturist extraordinaire, left his mark on Ucluelet and the surrounding area in a tangible way, literally blooming for all to see and enjoy. He was not only a Ucluelet pioneer, but “a true pioneer in his field.”34

George Fraser was born in Lossiemouth, Scotland, in 1854. At seventeen, he started work as a gardener at Christies Nursery in Fochabers, then worked at several other estates, eventually becoming head gardener at the country estate of Auchmore in Perthshire.

In 1883, twenty-nine-year-old George and sister Maggie emigrated to Canada. They crossed the Atlantic aboard SS Manitoban, landing in Quebec in mid-May. The ship’s name was serendipitous, as they settled in Winnipeg, where George worked on the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway. He also ran a greenhouse with a partner, John G. Johnson. Maggie married a local rancher and lived out her years in Manitoba. In 1888, George moved to Victoria, leaving the harsh Manitoba winters behind. John Johnson went with him.

In the balmier climate, George and John grew fruit and vegetables on their fifty-acre Craig’s End Farm. George also worked as foreman of the newly designed Beacon Hill Park. His legacy there remains, notably in the magnificent rhododendron garden near Fountain Lake. George worked under well-known landscape gardener John Blair, winner of the competition to design and construct the park.

In 1889, George purchased 136 acres on the north side of Sproat Lake, near Port Alberni, but found the land unsuitable for a nursery, so he looked to the milder, more humid climate of Vancouver Island’s west coast. In 1892, he purchased Lot 21 on the Ucluth Peninsula. The lot consisted of 236 acres, at a cost of one dollar per acre. These acres would one day become the main part of the village of Ucluelet.

George hacked his way through dense vegetation to create a space for his house and garden. He eventually cleared four and a half acres within a larger eight-acre area and set about, with perseverance and innovation, to establish his nursery.

He enriched the soil with seaweed, which was plentiful along the harbour, and with cow manure from the Lyche farm. George loaded the manure onto a scow, then towed it to his property with his small grey rowboat.

George tried fishing from his rowboat, with little success. One day, some Hitacu residents helped him out with a gift of fish thrown into his boat. Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ citizens gave him an Indigenous name, “As ka iik,” meaning “prone to having a dirty face,” appropriate for a full-time gardener such as George.

Most of George’s business was conducted by mail. The plants were sent away carefully wrapped in sphagnum moss, inside crates made from driftwood. His 1915 catalogue of stock showed a large variety of available plants. The even more extensive 1925 catalogue is entitled “Azaleas, Heather, Hollies, Roses, Pernettyas, Rhododendrons, and other shrubs and plants including Native Hybrids Grown by George Fraser.”35 George was successful with creative plant hybridization, crossing domestic species with plants native to Vancouver Island.

George consistently shared plants, cuttings and gardening information not only with local settlers, but farther afield. Resigned to the fact that his chosen passion would never lead to riches, he wrote in 1936: “There is one beautiful thing about our business, there is no danger of us making too much money that we are likely to be kidnapped.”36 George was philosophical about Ucluelet’s depleted soil and prolific weeds, but complained of the irrepressible deer. He said only the smallest shrubs escaped them, adding: “They can only be shot by pit-lamp and there is a five hundred dollar fine.” Present-day gardeners in Ucluelet still struggle with the voracious deer.

George exchanged seeds with Jennie Butchart, the driving force behind Victoria’s world-renowned Butchart Gardens, and some of his plants still bloom there, in what is now a National Historic Site of Canada. During World War II, George planted a favourite Scottish heather called Calluna vulgaris along the Tofino airfield runways. He gave packets filled with seeds to pilot friends at the base. At his request, they scattered the seeds from their planes as they flew over the mountains near Ucluelet. Calluna vulgaris now grows in many spots around Ucluelet and Tofino.

When the town threw George a party on his eighty-third birthday, he danced, played his violin and sang several Scottish tunes. Fritz Bonetti yodelled, and his nephew Henry played the accordion. After the singing of “Auld Lang Syne,” “everyone joined in giving three cheers for Mr. Fraser.”37

George Fraser remained in Ucluelet until the last few days of his life. Nearing the end, his friends carried him to the boat that would take him to the hospital in Port Alberni. George told his friend Bud Thompson, “I don’t know where I’m going to end up but it really doesn’t matter, I’ve had my Heaven here on earth.”38 He died two days later, on May 4, 1944, at the age of ninety, in Port Alberni.

George Fraser was a humble, gentle soul. One wonders what he would think of his present-day fame. Memorials to him can be found in Victoria, in his home country of Scotland, and throughout Ucluelet. His legacy still blooms in the rhododendrons nurtured by Bob Sinclair in his Misty Gardens. Retired schoolteacher and avid historian David McIntosh is the local expert on George Fraser. Wanda McAvoy, Parks foreperson, has devoted years to nurturing George Fraser’s plants and his memory. Their work, along with the other members of the George Fraser Society, ensures his history and his rhododendrons continue to flourish. Rhodo aficionados Bill Dale and the late Dr. Stuart Holland also kept George Fraser’s legacy alive.

James Fraser

James Fraser was born in 1870 in Fochabers, Scotland. James and his brother William followed their half-siblings George and Maggie to Canada. Ultimately, like George, they ended up in Ucluelet.

When James arrived in “Eucluelet” in 1901, he first worked as a gold miner. When that fizzled out, he found some success in farming. The Daily Colonist of March 2, 1913, reported on his two acres of strawberries, describing the fruit as “pre-eminently suited” to Ucluelet’s climate.

In 1916, James married Ellen Louisa Binns in Ucluelet East. Their marriage illustrates the complex family trees found in small communities. Ellen, sixteen years younger than James, was the widow of Carl Binns’s brother George.

In 1918 and 1919, James was the watchman at the Ucluelet lifeboat station and lighthouse keeper at Amphitrite. His outspoken letters regarding employment there shed light on the trying working conditions.

In 1922, when a $10,000 grant was allocated towards the Ucluelet–Tofino road, James was foreman of a small crew who worked at “clearing and grubbing.”39

James passed away in Ucluelet in 1931, leaving Ellen once more a widow. In 1934, she married James’s younger brother William Fraser in Ucluelet. William had worked as an ironmonger’s assistant in Scotland before coming to Canada. He was customs officer in Ucluelet. William passed away in Port Alberni in 1942 at the age of sixty. Ellen continued to live in Ucluelet and passed away in 1973 at the West Coast General Hospital.

Herbert Hillier

Herbert James Hillier, a key player in Ucluelet history, was born in Victoria in 1873, and lived with his parents and six siblings on their Burnside area farm. When Herbert was just eight, he and his siblings were orphaned. Some of the children were adopted, splitting up the family. Family stories relate that Herbert and his younger brother Jack were in a Victoria orphanage for a time, then ran away, stole a dugout canoe and rowed across Juan de Fuca Strait to the US.40

The boys eventually returned to Victoria, where Jack was adopted by a farmer named Porter. As a young man, Herbert found work as a butcher at Victoria’s first slaughterhouse.

Herbert’s bride, Rosa Alberta Hess, was born in Oregon. Herbert brought her and their infant son William to Ucluelet in 1898, aboard SS Willipa. The young couple worked together, running a cookhouse to feed the gold miners at Wreck Bay. During the five years they worked there, an estimated $40,000 worth of gold was gleaned from the Wreck Bay sand.41

In 1902, Herbert was hired as foreman on construction of a road between Ucluelet and Tofino. Funds were limited and progress was slow, with heavy use of crosscut saws, picks, shovels and wheelbarrows. Work on the road would be sporadic over the years, and it was not completed until there was the need for an airport during World War II.

In 1903, Herbert, no stranger to manual labour, worked on constructing a government telegraph line between Port Alberni and Clayoquot. He then became a telegraph lineman and took his family to live at Curwen Beach, towards Toquart Bay. Seeing the need for a more sheltered site, Herbert relocated to what became known as Hillier Island.

Their son Bert later reflected on his parents’ decision to settle on the wild west coast. “Damn it man, somebody had to make a start. Somebody had to be content with cabins, outdoor plumbing, privations and hardships. Somebody had to make sacrifices and say, ‘This is going to be where we’re going to live from now on.’ And mean it. My folks meant it. They proved it.”42

Around 1907, Herbert transferred to Ucluelet as both telegraph operator and lineman, taking over from William Thompson, who had moved to Cape Beale to run the lighthouse. Herbert then switched from canoe to a small, open powerboat, which he named the Rosa, after his wife. He was said to have caught the first spring salmon inside the harbour from a powerboat.

The Canadian census of 1911 shows Herbert and Rosa living at Ucluelet, and Herbert’s occupation as telegraph operator. Rosa lists her occupation as “none” despite the fact she was keeping house for herself, her husband, their four young children, her husband’s brother and three boarders, one of them aged thirteen. I would venture to say Rosa Hillier had very little free time!

In 1935, Herbert was awarded the King George V Silver Jubilee Medal for his many years of service. He retired from his position as Ucluelet’s telegraph agent and lineman in 1937. Herbert proudly wore his long-service award ribbon on his lapel right up to his death.

Rosa passed away in the Port Alberni Hospital in 1942 and was interred in Ucluelet Cemetery. In his retirement years, Herbert devoted himself to his garden, acquiring plants and gardening tips from his good friend George Fraser. Herbert passed away in 1953 and is interred next to Rosa in Ucluelet Cemetery.

The Hillier Descendants

Herbert and Rosa’s four sons were also true West Coast pioneers. William Leslie “Bill” Hillier was born in 1897, in Portland, Oregon, and came to Ucluelet with his parents as an infant.

He married Elsie Annie Karn in 1922. Bill was a telegraph lineman, and the young couple lived at Port Renfrew and then Coal Harbour before moving back to Ucluelet in 1935. While Bill was based out at Hillier Island during the weekend, Elsie was busy at home with their three children, Enid, Frank and Don. Elsie was a true west coaster. One of Frank’s chores was to keep the fireplaces supplied with wood. His dad brought logs onto the beach, and Frank cut off blocks, then chopped them for firewood. He recalled one time when he was twelve and his mom, who was five feet tall and has been described as “just a slip of a girl,” came down to the beach and used the crosscut saw to cut off blocks faster than he could.

Bill and Elsie’s son Don, proprietor of Madden’s General Store, died in a tragic boating accident in 1969. There were ten people, both adults and children, aboard a five-metre plywood speedboat at Long Beach. They were circling Sea Lion Rock when the boat capsized, hit broadside by a wave. Don died in the horrific accident, along with his three-year-old son Todd and two boys from the Garnett family, aged fifteen and five.

Grant Garnett, once a teacher in Ucluelet, was visiting the area at the time of the accident. He, his wife, three of their sons and a young friend survived because of the heroic actions of Ucluelet fisherman Ernie Edwards and his seventeen-year-old grandson Paul. Ernie, a close friend of Don’s, was twenty minutes away when he heard of the dire situation. He rushed to the scene aboard his troller, the Tribute, and manoeuvred through breakers and among rocks while his grandson pulled the survivors, one by one, aboard the boat. Ernie and Paul were later awarded medals in recognition of their bravery. Don’s widow Betty was left with five children to raise.

Herbert Edward “Bert” Hillier was born in 1901 in Saanich.

Bert was a commercial fisherman and then a fish buyer. He also had two traplines, one along the shoreline to Maggie River, and one out on islands in Barkley Sound. Along the shoreline he trapped mainly raccoons and martens, and on the islands mainly mink and otter. In a speech he gave to the Chamber of Commerce, he said his Irish terrier went with him on the traplines, “fighting everything except its own shadow.”43 Bert commended that terrier as the spunkiest and most reliable animal he’d ever known, adding that over the years he’d shot around thirty cougars to defend his faithful dog. Bert described himself in the woods as “fit as a fiddle…and as happy as any man could be.” He loved the freedom of overseeing his own destiny, saying it was “worth a king’s ransom.”44

Bert and his wife Queenie had two daughters, Rosa and Victoria (“Tory”). Queenie passed away in 1946 and Bert eventually married his second wife, Coral Diplock. He lived out his years in Ucluelet.

George Barkley Everett Hillier was born in 1904 at the family home in Barkley Sound, which inspired one of his middle names. George was around three years of age when his family moved from Hillier Island to Port Albion.

George started commercial fishing at an early age, first trolling and then using the seine boats Manhattan I and Manhattan II. He then had the seiner Hillier Queen built by Wingen’s shipyard in Tofino.

George’s dogs, Whisky, Brandy and Pal, would swim after George and his boat across from Port Albion to the Ucluelet wharf, and on one occasion the Uchuck stopped mid-harbour as the three dogs passed her bow.45 George gave Pal to the Stuart family in the 1950s, and the huge black dog became the official greeter at Amphitrite Point.

George was an area co-ordinator of BC Search and Rescue. He participated in many rescues at sea, and towed countless disabled fishboats safely into harbour. He said he’d lost track of how many rescue trips he’d made, but “what the heck, tomorrow you might need help yourself.”46 Once, George rescued a man who was adrift after stealing George’s own canoe.47

When George fell ill in July 1964, some speculated he was suffering from paralytic shellfish poisoning. It was soon established he had polio, and he was rushed to a Victoria hospital and put in an iron lung. His was the last recorded case of paralytic polio in BC.48 When George contracted polio, a large number of vaccines were sent to Port Albion to immunize residents.

Ruth Tugwell, George’s cousin and dear friend, closed her store to be at his side. He was later sent to Vancouver for rehabilitation. George and Ruth were married in the Pearson Hospital chapel in 1965, with him in a wheelchair. Upon returning to Ucluelet two days later, they were greeted by over 150 friends and relatives, who had prepared a wedding reception for them at the Ucluelet Athletic Club Hall.

Peter Gordon “Pete” Hillier was born in Ucluelet in 1907. Pete recalled that while growing up, he never missed a day of school, despite having to travel by canoe across the bay to the little schoolhouse in Ucluelet. Like many west coasters of that era, he dropped out of school—in his case at age fifteen—to make a living. Pete worked in the machine-shop trade for four years, then went fishing. “Never owned a boat of my own,” he said, “but I captained my brother’s [George’s] boat all the time. I must’ve been in every nook and corner on the BC coast as far as Prince Rupert.”49

Like his brothers, Pete was a trapper and hunter who thought nothing of packing deer carcasses back to the village from Long Beach.

Pete married Ethel Anderson of Tofino in 1943. The couple had a son Leslie, and two daughters, Linda Sohier and Joan Gates.

In 1956, Pete left fishing to return to work in a machine shop. After three years as an employee, he bought the business situated at the foot of Fraser Lane. After selling the business in 1972, Pete drove school buses and volunteered in the community.

Thomas Tugwell

Growing up in Ucluelet, I knew there was a strong connection between two long-time settler families, the Hilliers and the Tugwells. When I delved into research, I discovered the fascinating story that binds them together.

Thomas Tugwell Jr. was born in 1879 to William and Elizabeth Hillier, parents of the aforementioned Herbert Hillier. Elizabeth died on Christmas day of 1881, after giving birth to a baby girl. When Willliam died the following year, prominent Sooke rancher Thomas Tugwell and his wife adopted one-year-old Elizabeth and three-year-old Thomas. Thomas later stated that the couple adopted him to keep his sister company.50

For a time, Thomas and sister Elizabeth worked with Thomas Sr. in the Yukon, where (according to the explorenorth.com website) they advertised their roadhouse as “the only wooden building with rooms.” Young Thomas also delivered the Royal Mail between Log Cabin and Atlin. In winter he travelled by dogsled, and in summer by rowboat or on foot.

Around 1906, Thomas Jr. visited Ucluelet, reconnecting with two of his brothers, Herbert and Jack Hillier. He had previously been up the coast with his adoptive father in 1897, on a prospecting trip aboard SS Tees.51

After a short stay, Thomas Jr. headed north again, becoming postmaster at Log Cabin. He returned to live full time in Ucluelet in 1910, taking his place as one of Ucluelet’s pioneers.

Thomas’s wife, Agnes, was a capable, resilient woman who in her early teens helped her father with placer mining in the Yukon and drove the family dogsled seventy-two kilometres daily to work at Atlin Hospital. The nurses recognized a natural talent. With their encouragement, Agnes studied at Prince Rupert Hospital, graduating in its first nursing class. Upon marrying Thomas Tugwell Jr. in Vancouver in 1915, Agnes gave up her “official” nursing career. However, many benefited from her medical knowledge in the ensuing years.

Thomas brought his new bride home to Ucluelet by steamer. They were welcomed at the dock with a shower of rice. A carpenter by trade, Thomas had been busy building a home at the corner of Main Street and Peninsula Road. It was not quite finished, so the couple lived for a time with his brother Herbert and family at Port Albion. They then moved to Spring Cove, where he worked at the lifeboat station.

In April 1916, the new home was ready. At the writing of this book, the house still stands. When the couple’s first child was born, Thomas switched to employment at a fish plant across the bay, in order to work day shifts. When BC Packers brought a fish-buying scow into Spring Cove, he was hired to run it.

During the Depression, Thomas worked as a cook for a camp of unemployed men. Then, in 1940, with the help of his family, he built a bakery near the top of Main Street hill, next to their house. He and Agnes ran the popular Tugwell’s Bakery until 1958.

Thomas passed away in 1959 at his home in Ucluelet. The funeral was held in St. Aidan’s Church, and Thomas was interred in Ucluelet Cemetery. Agnes passed away at a private hospital in Burnaby in 1971 and was interred next to her beloved husband. Thomas and Agnes had four children: Ruth, Thomas “Bud”, Beth and Bernard. They, like their parents, contributed greatly to the community of Ucluelet.