Chapter 17: The Bounty of the Sea

The Indigenous Peoples of the West Coast have always had a strong connection to the sea and faith in their inherent rights to fish. The nuučaan̓uł traditionally harvested salmon, cod, halibut and herring. They caught salmon, their staple, with spears, nets and weirs. Every bit of the salmon was used—they cooked the heads, fins and tails, and smoked or dried the rest of the fish, as well as the roe.

They placed cedar or hemlock branches in water where herring was known to spawn, then lifted out the branches to harvest and dry the roe. These methods are still used today. Small wooden rakes edged with sharp nails were used to catch herring. It was not a popular food fish for the nuučaan̓uł. They mainly preserved it to trade with other nations.

The colonial traders arriving on the coast soon recognized the abundance of fish and the opportunity for commercial ventures in Barkley Sound. Captain Peter Francis set up salmon salteries at his trading posts, creating a product destined for trade in Honolulu.

In 1886, Mr. Youdell, acting inspector of fisheries, researched fishing banks off the west coast, describing the waters of Barkley and Clayoquot Sounds as “a fisherman’s paradise. There is good shelter for craft, an abundance of timber suitable for boats…in fact, every favorable facility for fishing purposes.”1

By the 1890s, the Daily Colonist was reporting thousands of cases of salmon arriving in Victoria from the Clayoquot cannery, stating: “The supply of fish greatly exceeds the capacity of the cannery.”2 The cannery, situated where Kennedy River runs into Tofino Inlet, existed from the late 1880s to 1931.

There was also no shortage of dogfish. These small sharks were a source of oil, an important product the nuučaan̓uł traded. Dogfish oil was used for lamp fuel and industrial lubricants, by sawmills, coal mines and ships. It was said to create superlative lighting—two lighthouses on the coast used it exclusively for their lights.3 Dogfish was processed for fertilizer, and never became popular as an edible fish in North America. Fishermen consider them a nuisance fish, notorious for ripping catches right off the lines.

August Lyche found a market for dogfish in East Asia, and in 1904 held the dogfish licence for all of Barkley Sound. That licence cost August fifty dollars; he processed over a million dogfish. August had a salting shed in Ucluelet and a plant at Toquart, as well as a building at Hayes Mine and a leased cannery at Kildonan. Five boats supplied most of the fish to his plants during a three-month season. These boats were powered by a crew of eight, each man on one oar, plus a seine boss who steered the boat and took charge of the net.4 August bought his salt from Mexico at six dollars a ton. The salted fish was packed in boxes built at Sutton’s Mill, then taken to Seattle to be shipped on sailing vessels to China.

In 1895, Captain Hamilton R. Foote of the steamer Mischief arrived in Victoria to report that while out on the west coast he was informed of “the first visit of the genuine mackerel to the coast of Vancouver Island that has yet been heard of.”5 Subsequent newspaper issues frequently mentioned herring, and it is possible that Foot had heard of herring rather than mackerel.

Around 1910, a small saltery was established in Ucluelet to provide herring for the Japanese market. The fish were caught with seine nets inside Ucluelet and Toquart bays, mainly by four men from Scotland—brothers Dan, Billie and Johnny Bain, and Jim Barnes—with two boats, the Ucluelet No. 1 and the Tofino.6 The Daily Colonist of March 15, 1911, reported the arrival of the SS Tees with 170 tonnes of salted herring from Ucluelet, destined for Asia.

Sea Lions: Fisherman’s Foe?

As fishing thrived on the west coast of Vancouver Island, fishermen decried the impact sea lions had on the industry. Some frustrated fishermen took action, as reported in the Alberni Pioneer News in 1912. Thomas Horne and W.E. Miller of the Ucluelet fishing post, along with H.J. Hillier of Ucluelet and several others, were in the middle of Barkley Sound on their way to Port Alberni when they encountered a herd of sea lions. “There must have been a thousand of them,” one of the party later said.7 The men turned their rifles and two hundred rounds of ammunition on the herd. “They were all such big fellows, and such easy marks, that I don’t think one of us missed a shot.”8

Herbert Hillier’s four sons were also known on occasion to use their rifles for dispatching sea lions; when they got caught up in going after sea lions, someone would invariably call, “Hey, who’s steering this boat?”9 On their way back to port, they took sea lion carcasses to some First Nations Elders who used them for food. Edwin Lee, secretary of the Ucluelet branch of the Vancouver Island Development League, visited Victoria in March 1913 and urged the government to take steps to “remove the plague of sea lions which are proving a serious detriment to the fishing industry and causing much damage to the nets.”10 Lee suggested their skin and blubber could have a commercial value that would tie in with any wholesale destruction. The attorney general’s department assured Lee it would do a thorough inquiry. However, the Daily Colonist article expressed concern that doing away with the sea lions could upset a necessary balance. The article also foresaw limited commercial value for the hides, although a glovemaker claimed he could make stout workman’s gloves from them.

Many West Coast fishermen continue to complain about the negative effect of sea lions on available catch. Mike Smith said they aren’t too bad if there are a few boats and lots of fish, but if you’re on your own and there are sea lions around, they will get your fish, so you might as well leave. Mike added, “They know a fish is on before you do.”

The Wallace Brothers

In 1913, two Scottish brothers named Peter and John Wallace opened a fish buying post in Ucluelet. Fishing in the area was thriving. Herring were so prolific that in 1915 some fishermen in Barkley Sound complained that spring salmon “could not be tempted with artificial bait.”11 However, Bert Hillier reported success with catching spring salmon: “I sold the first salmon in 1915. My brothers and I caught Spring salmon at the mouth of the harbour and sold them for 50 cents a piece and of course $10.00 was a fortune to us in those days! We didn’t know what to do with the money.”12

In 1915, the Daily Colonist showed Bert’s father also had a knack for catching salmon: “Mr. H.J. Hillier, telegraph operator at Ucluelet, and Mr. C.C. Binns, member of Ucluelet lifeboat crew, have earned a great reputation as fishermen among natives of the west coast of Vancouver Island by reason of the skill displayed in landing a 60 lb. salmon from a small boat in a choppy sea…Although a larger fish is reported to have been caught at Ucluelet, the one handled by Hillier and Binns is declared the liveliest that was ever induced to grasp at the business end of a spoon bait.”13

Wallace Fisheries maintained a strong presence, causing conflict when some individuals were told they couldn’t establish small canneries. The disgruntled entrepreneurs cried foul, complaining the Fisheries Department favoured the Wallaces. In 1916, Ucluelet fisherman Christian Olsen refused to co-operate with Wallace Fisheries and was denied a dogfish licence. In 1918, when he finally got a gillnet licence, Fishery Inspector Woods stipulated Olsen could not use the licence in Ucluelet Harbour.14

Complaints from independent fishermen and buyers regarding favouritism shown the Wallaces led to an inquiry in February 1919, but government policies and the fisheries officers’ conduct were upheld.

By the 1920s fishing was a million-dollar industry in BC, composing about one-third of Canada’s total fisheries. Approximately twenty thousand people then worked in BC’s fishing industry.

Port Albion

A variety of seafood and fish was processed at Port Albion. Around 1920, there was a clam factory, which, Bert Hillier said, “lasted only a year or two then it went hay wire.”15

The Bamfield Packing Company, a subsidiary of the Nootka Packing Company, built the Port Albion Cannery in 1927. It was jointly owned by the Nootka-Bamfield Packing Company and Canadian Fish Company before BC Packers purchased it in 1937.16 In its heyday, the Port Albion reduction camp handled nine thousand tonnes of herring and pilchards, and the cannery processed up to 450,000 kilos of salmon per season.

A 1936 Victoria newspaper raved: “An increase in the production of all fisher products is reported all along the coast. Fresh fish, canned salmon, oil, fish meal, fertilizer, herring and pilchard products, and salt fish plants all had a very active season, with fish reported plentiful and a better market offering for all products.”17

The Port Albion camp employed up to a hundred workers. There were separate cookhouses for men and women, bunkhouses, a blacksmith shop, a boat ways, a store and family homes. “Cannery girls” came to Port Albion to work, many of them living in the bunkhouse. Marion Hardy (née Ellison) arrived aboard the Uchuck II at the age of fifteen and worked in the cannery for five months. She made good money, sending her mom a sizable chunk of her monthly paycheque. “It was interesting and fun here…between whistles when you had to go to work, she said.”18 In their spare time, the cannery girls rowed around the harbour, walked the boardwalk to Spring Cove, attended parties at the seaplane base, swam off the Whiskey Dock and saw plenty of cougars. The cannery also brought Vonda Ball of Saskatchewan to Port Albion. When Bud Tugwell heard her laugh, he knew she was the one for him—Vonda married Bud and became a lifelong Ucluelet local.

Albert Jacobs had a thriving garden and delivered vegetables to the cookhouses twice weekly in his wheelbarrow. His property was on a flat plot of land at what came to be called Jacob’s Lake (Ittatsoo Lake). The lake provided sanctuary for trumpeter swans. Albert documented numbers of the endangered birds, sharing statistics with the protection society. Albert and his wife came to Canada from the Isle of Wight aboard the Carpathia. He recalled their ship diverting to pick up survivors of the sinking of the Titanic.

Lloyd Bridal moved from Calgary to Port Albion with his parents and five siblings in 1944. His father had found a job at the fish plant, and bought a two-bedroom house on seven acres in the woods. Lloyd and his brother soon had a small room with bunk beds in the enclosed back porch. Fish-meal fertilizer was stored in the attached woodshed, and the boys once awoke to a bear scratching at the door.

The family raised goats, including a “big white dirty old billy goat” named Sylvanus and a little milk goat named Lindy-lou. Lloyd said they were the “best playmates we could have had…If you butted them, they would butt right back.”19

Lloyd’s father worked at processing herring and pilchard oil, which went through a series of vats and came out “clear like codliver oil.” Once the oil was rendered, the remains went through a large revolving dryer and were turned into fertilizer that was packed into sacks. One night shift, young Lloyd went to help. “I couldn’t stay awake all night, so the boys let me have a nap on some warm sacks of fish meal.”20

The rendering process made a slick, smelly mess on the water and along the beach, all the way to Hitacu. With his characteristic dry humour, Bob Mundy later said with a smile, “I remember that fondly.”21 Both Bob and his wife Vi worked for a time at the plant.

After canning ended in 1948, the Port Albion plant continued for another decade and was the last herring reduction plant on Vancouver Island.

When the Bridals lived in Port Albion, the Baldwins ran the store. It was later managed by Guy Taron, after he, wife Winnie and six children moved to Port Albion from Penticton in 1959. His store was known by some as the “Gambling Hall/General Store.” On the second floor, there was a pool table, dartboards and televisions. Poker games often went late into the night. Down below was the post office and store, where Guy sold all manner of things. He was a skilled butcher, supplying meat to locals and visiting fishermen. He also had a wide variety of snacks and treats. Vi Mundy recalled that Guy was always kind to the kids, taking time to chat with them and not charging them for candy.

Wojtek Malach managed the Bornstein Seafoods plant in Port Albion for twenty-four years, which frequently handled twenty-two million kilos of shrimp per year. When Wojtek came home and his wife commented that he smelled fishy, he told her, “It’s the smell of money!” Since Bornstein sold in 2014, Wojtek has managed the new business, Tinlet Fishing. The unloaded fish is graded, shipped to Canadian processors, and sold worldwide. At age seventy-six, after fifty-six years in the fishing industry, Wojtek says, “I wasn’t raised to sit and do nothing.”

Pilchards

As illustrated in the January 3, 1937, edition of the Capital Times newspaper, pilchards were referred to in the US as “California sardines.”

By the late 1920s, the pilchard fishery was massive on Vancouver Island’s west coast, with thousands of tonnes caught. Twenty-six pilchard reduction plants were built on the west coast between 1925 and 1945. Seasons lasted four to five months, with the plants together employing about five hundred men on boat crews and the same number of shore workers.22 Six of those plants were in the Ucluelet area. The plants opened and closed in sync with the comings and goings of these fickle fish. The pilchard season peaked in 1936–37, then numbers dropped. According to my uncle Art Baird, in 1947 the pilchards mysteriously disappeared.

Some people believed the pilchards had been fished out. Others thought their migration patterns had changed. The pilchard spawning grounds are in California, and from there only the larger fish make it up to the BC coast—it was suggested they were going elsewhere.

Numbers gradually dropped in California as well, and in 1967 the state declared a moratorium on fishing pilchards. Twenty years later, pilchards came back up off the California coast, and the recovery was credited to the moratorium. However, historical data on water current temperatures and catch records pointed to climate changes—the shift between warm and cold currents affected plankton population, which in turn affected pilchard population.23

When the pilchards returned to the BC coast in the 1990s, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) issued some temporary licences to fish them. At this time, “sardine” became the moniker of choice for the oily little fish (Latin name: Sardinops sagax). The reduction plants and canneries were long since gone, as was the market for oil and meal.

Japan provided the market for the revived pilchard/sardine fishery. The buyers coveted perfect fish, and the large (two-hundred-gram) sardines of the BC coast fit the bill. They were frozen at sea and sent to Japan, not only as prized menu items but as tuna bait.

In the life of the ocean, everything is connected. Many people attribute the return of humpback whales along our coastline to the return of the pilchards. From 2010 to 2012, there were frequent humpback sightings, from near shore out to an area of deep, ocean-floor canyons. Dan Edwards recalls being surrounded by over a hundred humpback whales while fishing ninety kilometres off Ucluelet, at Barkley Canyon. In 2013, when the pilchards disappeared again, sightings of humpbacks dropped dramatically. There has again been an upsurge, but humpbacks are still a species of concern.

Herring

Pacific herring average about twenty-three centimetres in length, are a pretty bluish-green and silver, and travel in large schools. My aunt Mary Baird recalled that when she was a child, “the bay was so full of herring that when the tide went out at the head of the inlet, there’d be herring all along the beach, and we’d just go and rake them in, and make kippers.” She added: “They took so many out of the bay that it just finished it.”24

Pacific herring cover a range from Baja California to the Bering Sea. According to the DFO, when the Pacific sardine fishery collapsed, the Pacific herring fishery became, for a time, the major pelagic fishery in BC.25

Herring was in demand in parts of Asia for many years, but when the market for dry salt herring failed, it was a concern for the fishery. Then, in 1935, permission was given in BC to reduce large quantities of herring, boosting the industry and employing hundreds of workers at reduction plants. The Times Colonist of January 2, 1936, described reduction as allowing “this much-maligned industry to get on a stabilized basis.”

Reduction plants were controversial. In March 1936, BC resumed its pre-Depression studies to “determine whether herring should be used for non-food fish purposes or not.”26 The BC Trollers Association, at a three-day conference in 1936, advocated fish conservation and opposed reduction of pilchards and herring.

Herring, like pilchards, became elusive. They were deemed largely fished-out by the 1960s, and many BC fishermen went to fish herring seasonally on Canada’s east coast. Then, in the early 1970s, herring once more became a big fishery on the West Coast, this time as a roe herring fishery split between a big-boat seine fishery and small-boat gillnet fishery. There were so many boats catching so many herring for so much money, it was likened to a gold rush. The herring were mainly fished by large purse seiners, boats upwards of thirty metres in length and able to carry 130 to 180 tonnes of herring.27

During herring season, Ucluelet reeked of fish—a.k.a. “the perfume of prosperity.” Fishermen with wallets bulging with cash bought round after round at the Lodge. Herring fishermen loaded up their shopping carts at the Co-op for their next trip out, stripping store shelves bare. There were so many herring boats side by side in the harbour that it was jokingly said you could walk deck to deck, from Ucluelet across the bay to Port Albion.

Local fishermen followed the openings. Mike Smith and Dan and Paul Edwards headed up to the Charlottes (Haida Gwaii) one year to fish herring, got caught in a foul storm and made a run for Port Hardy. It took seven hours to go thirty kilometres—Dan described it to me as “kind of brutal.” Upon reaching the Charlottes, they spent a month anchored in an inlet, afraid to leave and miss the herring fishery opening. They ran out of food, so they jigged for rockfish and ate scallops.

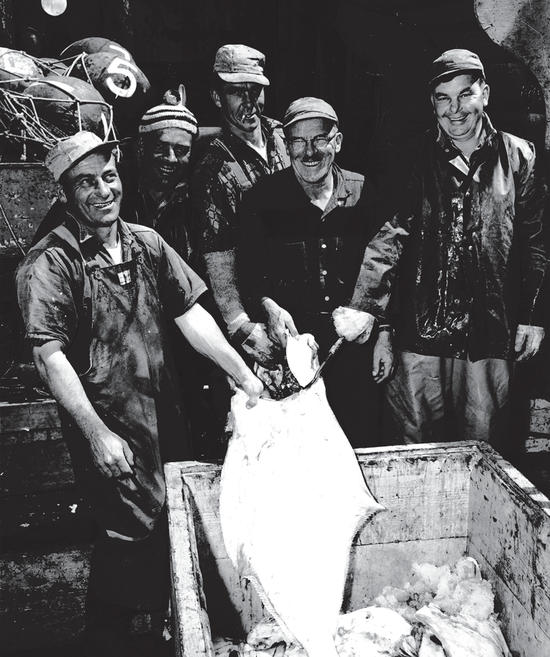

The herring boom continued into the 1980s as a lucrative herring roe industry. In March 1987, 14,500 tonnes of herring were taken by ninety-five seiners at Barkley Sound during the three-hour opening. Local processors Ucluelet Seafood Processors and Transpacific Fish froze the herring, with plans to commence picking roe within the next few weeks. The largest catch, estimated at close to eight hundred tonnes, was taken by the Vancouver boat Snow Cloud. A Vancouver Sun report predicted a potential wholesale selling price of $7 million in Japan. It’s no wonder the Snow Cloud’s owner greeted the seiner’s six-man crew at the dock with a half-dozen bottles of champagne.28

Herring openings were intense. Dan Edwards said the many days of waiting for the DFO to declare an opening “could be really hard on the liver,” and garbage cans sometimes brimmed with empty vodka bottles. The frequently wild weather added to the stress. With the DFO’s go-ahead, boats rushed into the designated area, competing to harvest as much as they could in periods often as short as half an hour to two hours. The DFO closed the area as soon as the total allowable catch was achieved.

When the system changed to individual quota allotments, the pressure to compete was off. Quotas per boat were based on a year’s total allowable catch. Some fishermen preferred the quota system, as the “Olympic style” fishing meant they pushed themselves too hard, sometimes in dangerous weather.

The commercial roe herring fishery on the west coast of Vancouver Island closed in 2006 because of conservation concerns, but it continued in other areas of the coast. Nuu-chah-nulth nations appealed the opening of a herring fishery in 2014 and an injunction was enforced. Their concerns aligned with the DFO, which supported the continued closure.

Roe on kelp is an alternative fishery, following the Nuu-chah-nulth tradition of harvesting roe from flat kelp or branches submerged in areas where herring are known to spawn. This is a sustainable and unique fishery, as the herring swim free. The majority of roe-on-kelp licences are issued to First Nations harvesters.

Hake

Hake, also called Pacific whiting, are slim fish with large eyes. A semi-pelagic fish, they roam from ocean floor to mid-water, where they are caught by mid-water trawl. The flesh of the hake is white, and the flavour is mild, somewhat like cod.

For a time, Ucluelet had a bustling industry of producing surimi from hake. (Some people consume surimi as imitation crab.) Then, in 2003, mad-cow disease ended this production, as dried beef plasma, a key surimi ingredient, was no longer available. Hundreds of workers commuting from Port Alberni to Ucluelet lost their jobs. Julie Edwards, then general manager of Wholey’s, one of Ucluelet’s hake plants, focused on processing and selling the hake as fillets, which brought new life to the hake processing plant.

In 2017, seventy-seven thousand tonnes of hake (nearly six times the province’s wild salmon catch) were harvested off the BC coast.29 Hake is popular in many countries, but not here in BC, where it is abundant.

Fish plant workers are an integral part of Ucluelet’s fishing port history. Lorry Foster worked at TRAPPA (Transpacific Fish) for twenty-five years, for “good union wages,” with a well-liked manager, Carl Scott. The shifts were long, requiring stamina and focus, as up to twenty filleters, along with weighers and packers, concentrated on the task at hand. Lorry said that over the years they processed “everything,” including groundfish, salmon and herring roe, but by the time she retired it was all about hake.

The women (and two men) on the line developed a strong camaraderie, and Lorry described her job as lots of fun. They had “crazy hat days”—Mary Kimoto once arrived at work sporting an octopus chapeau. One Easter, Lorry worked the line dressed as a duck. The women also enjoyed excursions together, including one to a filleting competition in Bellingham, Washington. The fish plants were a huge presence around the harbour. In 2001, there were seven hundred employees working in three plants.

Jan Smith was inspired by her work at Central Native Fishing Co-op to write a song called “Gut Sorting Blues.” The piecework shifts were long and cold. After fourteen-hour workdays, she slept in “Studio One,” a parking-lot trailer where the propane heater never dried out the damp, smelly work clothes. Jan eventually met her husband-to-be Mike Smith, went deckhanding and embraced being on the water, but she cherishes memories of the amazing women she worked with at the fish plant.

Halibut

In 1910, settlers William Thompson and Carl Binns had a halibut fishing business based in Ucluelet. Halibut fishing is still going strong today. The Pacific Coast halibut fishery is considered a successful model of fisheries management and international co-operation. The International Pacific Halibut Commission has managed this fishery since it was established by a convention between Canada and the US in 1923. Its objectives are to develop the stocks of Pacific halibut in the convention waters to levels for optimum fishery yield, and to maintain those levels.30

Dogfish

Like other fisheries on the west coast of Vancouver Island, the dogfish fishery waxed and waned. It flourished again in BC around 1996, with the fish caught mainly on the west coast and landed in Ucluelet. From here, they were sent to England for fish and chips; the belly flaps went to Germany to be smoked, and the fins to Asia for the shark fin soup market. What remained was processed for fertilizer in a plant in Delta. The dogfish fishery collapsed in 2011 because of rising fishing costs and low fish prices. There is a concern that World War II use of the liver for vitamin A may have decimated BC dogfish stocks. (Vitamin A was purported to improve combat troops’ night vision.) The DFO is currently assessing stock status and recovery rates.31

The Fishing Fleet

Fishing is not only a source of income. For many, it has been a way of life, combining ingenuity and resilience with long hours at sea. A 1967 Times Colonist article described the troller fisherman as “tough and fiercely competitive. For tinkering and experimenting he has no equal among fishermen. He relies on sophisticated electronics, blind hunches and a bewildering array of spoons, flasher, wobbler and plugs to fool the fish.”32

Japanese Canadian fishermen started coming here in 1916, drawn by large numbers of salmon.

A 1919 fishing inquiry raised concerns about the influx of Japanese Canadian fishermen to the island’s west coast. That year, 3,267 licences (almost half of those issued) went to Japanese Canadian fishermen. The Department of Fisheries responded to complaints by reducing the number of trolling licences to Japanese Canadians each year.

Most of the Japanese Canadian fishermen originally fished here seasonally. Then, in 1923, when the Department of Fisheries insisted that only residents could fish the waters of the west coast of Vancouver Island, fifty-two Japanese Canadian fishermen and their families moved to Ucluelet.

In 1926, forty-five white residents of Ucluelet submitted a petition requesting there be “no further reduction in issue of salmon trolling licenses to the Japanese settlers and residents of Ucluelet, BC.” Paul Kariya points to an element of economic self-interest in the petition, as the Japanese Canadian fishermen contributed to economic growth.33

As their number of trolling licences continued to be cut back, the Japanese Fishermen’s Association went to court in 1928 to state its case. The Supreme Court of Canada upheld their rights as naturalized Canadian citizens to receive commercial fishing licences. During that time, many of the white fishermen recognized the skill and expertise of the Japanese Canadian fishermen, and some formed partnerships.

Paul Kariya, in an article in Nikkei Images, illustrates the Japanese Canadian excellence as trollers. Paul’s uncle, Shigeru Nitsui, was high boat for Ucluelet (meaning he had the largest catch) for nine years in the 1930s, winning a Japanese consulate–sponsored trophy “as big as the Stanley Cup” for his skill.34

The Japanese Canadians continued to be an important part of the fisheries on Vancouver Island’s west coast until World War II. Some would later take up their original livelihood on the west coast, but, after internment, many never moved back. Around twenty fishermen and their families returned, becoming important members of the Ucluelet community.

Many names consistently show up in early records of Ucluelet commercial fishermen. As the years went by, the fleet increased. I cannot possibly list them all or tell each and every unique story—that would require another book. I will have to settle for telling stories about a few families, starting with (author’s privilege!) my own.

The Bairds

The Bairds settled in Port Renfrew in the late 1800s, and my father and his six siblings were raised there. Dad and his brothers all worked at fishing and logging. Their only sister married a logger, and when he died in a logging accident, she married another logger.

At various times, Dad and three of his brothers, Art, Gordon and Harold, fished out of Ucluelet.

Although Dad, Uncle Gordon and Uncle Harold all had long careers as loggers, Uncle Art fished for most of his life. When he moved to Ucluelet in 1926, his first troller, the Anna, was named after his sister. Uncle Art found the boat with a hole in its hull on a beach near Port Renfrew. “We put a makeshift patch on her to get her floating. My brother helped me take it off the beach and we did a proper job on her at the logging camp.”35

Uncle Art and his wife Mary lived next to the harbour, and over the years moored four different trollers there. When he retired, his last one, the Ocean Isle, stayed in the family. Art and Mary then had time for trips in their ten-metre pleasure craft, the Simpson. But being a Baird, Uncle Art was unaccustomed to leisure time. He took on a career in adjusting marine compasses and teaching navigation courses through North Island College.

Art’s sons both commercial fished. Alan started fishing in his early teens, soon buying the Hi-Yu. When Uncle Art retired, Alan bought the Ocean Isleand carried on fishing. Like Alan, Brian deckhanded early on. At age eighteen, after graduating from Ucluelet Secondary School, he bought the Brant from Russel Clark. The boat had a family connection, as our uncle Gordon had built the Brant’s wheelhouse. Brian’s next troller was the Silver Mist. At the age of thirty-six, Brian left commercial fishing to go into building houses, so he could have more at-home time with his young kids. After years of carpentry, he still loves to get out fishing.

The Edwards Family

Ernest Edwards started fishing in a dory off the Newfoundland coast. In his teens, he deckhanded aboard a schooner between Harbour le Cou and New York, delivering cod and returning with coal. Not taking to the schooner life, he moved to Victoria in 1919 with his brother Jonas, where they jointly owned a halibut boat. Ernie’s original plan was to become a captain on a CPR vessel, but he was unable to move past the position of first mate, owing to failing eyesight.

Next, Ernie commissioned the building of an eleven-metre troller, the Glencoe II. He married Janet “Jen” Homans, and in 1927, “to the horror of Janet’s friends and family,” moved to Ucluelet. Jonas and wife Pearl were already here, and the brothers built houses next door to each other, on Peninsula Road, at the top of Main Street.

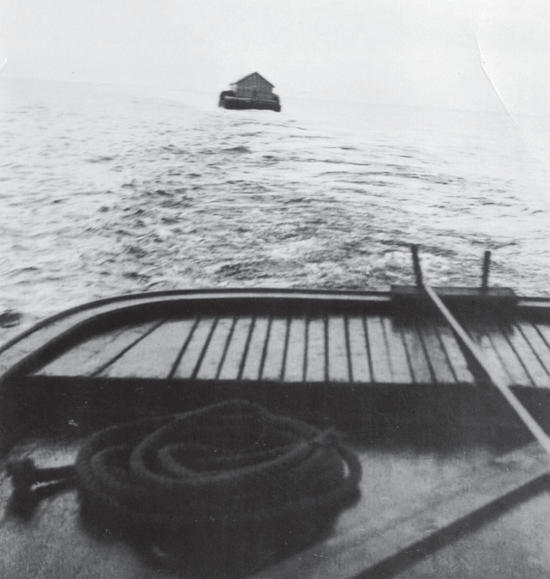

Ernie had a larger (twelve-metre) longliner/troller/seiner/tuna boat, the Glen E, built in 1949. It was named after their only son, Glen, who by age thirteen was deckhanding with his dad.

Glen went on to fish his trollers the Effie G. and the Wanderer II, and next the thirteen-metre Ocean Foam. He and his wife, Joey, had eight children, most of whom went on to work in the fishing industry. Some of his grandchildren followed in their footsteps.

Another member of the family fishing dynasty, Ernie and Jonas’s nephew Gordon, arrived from Harbour le Cou in 1938. One of a group of fishermen who founded the Ucluelet Fishing Company, Gordon was a “highliner.”36

Elling Reite

Elling’s father, Peter, came to Ucluelet in 1911 aboard a survey ship, and was given the task of building a trail to the top of Mount Ozzard. From there, he looked down on a pretty little lake. Forty years later, he would retire there on a homestead on Jacob’s Lake with his wife, Anna. But in the intervening years, Peter would return to Norway and raise a family, often returning to BC for extended periods of employment.

Peter’s son Elling was back home in Norway, commercial fishing and helping run the family farm. After World War II, he repaired lighthouses damaged by bombing. But Elling was ready for a change and convinced his wife, Jorunn (June), to emigrate to Ucluelet, a place his father described in glowing terms. Elling and June raised their six children here.

After many years, Peter was finally able to bring his wife, Anna, from Norway to Ucluelet. When they arrived aboard the Uchuck, Elling, Jorunn and friends and neighbours were on the dock to welcome her. Anna loved their homestead. She had brought her old guitar; sitting in the living room, she spontaneously composed and sang a song about their new home on the lake.

Anna had a prized pearl necklace, given to her by her brother Jakob before he passed away at an early age. She wore it to her first gathering in her new town. Everyone was dressed in their finery for the annual Christmas party in the community hall. Santa had distributed gifts to all the children, tables had been moved and couples were dancing to a lively Scottish tune. Suddenly, there was a loud shriek, as pearls from Anna’s broken necklace skittered across the floor.

The music stopped. Everyone was down on the floor, picking up Anna’s pearls. Elling described his mother: “A teardrop was rolling down her cheek…not a tear of despair but one of surprise and joy for the care that all the people so lovingly demonstrated seeking her lost pearls.”37 All of her pearls were handed to her in a glass bowl. Elling and Jorunn remembered that event as a symbol of how welcome they felt in their new west coast home.

Albert Larsen

Albert Larsen grew up in the small cannery community of Kildonan. He started fishing at the age of thirteen with a gillnet in a skiff. His boats kept getting a bit bigger.

Albert served in the army during World War II, including a stint protecting the Aleutian Islands. After the war, he returned to Kildonan and bought his troller the Lone Ranger. He met Dorothy McIntosh when she was visiting there, and the young couple soon married. Dorothy learned to mend nets while living in Kildonan, and found being married to a fisherman “a bit of a shock.” Growing up, she’d been used to her father coming home at the end of each workday, but Albert was away fishing for days at a time.

The newlyweds soon moved to Ucluelet, where Albert continued to fish, and they built their home on Helen Road in the off-season. They raised five children, most of whom deckhanded with Albert at different times. Their eldest son, Darryl, became a commercial fisherman and perished at sea in a tragic accident.

When the youngest kids grew up and left home, Dorothy took over deckhanding with Albert, usually on ten-day trips packing ice. She enjoyed being out on the water, and in nineteen years of fishing never got seasick. Albert got seasick every spring, at the start of fishing season, but soon adjusted. At the age of seventy-eight, Albert was still commercial fishing with his troller the Argo.

The Three Amigos

Long-time friends Doug Kimoto, Dan Edwards and Mike Smith often fished together. Known as the Three Amigos, they also belonged to a local trolling group called the Queen’s Cowboys, whose members shared fishing hot spots and information on a private radio channel. Doug, Dan and Mike were dedicated fishermen and strong advocates for local fisheries.

When Douglas Shigeru Kimoto passed away in 2021, he had dedicated close to sixty years to commercial fishing. He, like his older brother Gordie, had followed in their father Tommy Kimoto’s footsteps. Doug said he was in love with fishing “ever since I could stand on an apple box in the stern.”38 Doug worked long and hard in advocating for the survival of his beloved west coast fishery, sharing concerns about the management of the salmon resource. In 2020, he told reporter Nora O’Malley: “Years ago you could make a decent living, but now it’s down to what you’d call not even a minimum wage.”39 Doug left a legacy of ethical commercial fishing and devotion to salmon stewardship.

Mike Smith grew up in a logging family; he would have tried logging, but he was eager to work and didn’t want to wait until the requisite age of eighteen to get hired in the woods. Mike started working in the fish camps, seven days a week for low wages, with shifts that sometimes went thirty hours straight. He and friend Dick Nitsui asked for a raise. When told no, they both found deckhanding jobs. Mike soon had his own troller, took to the independent lifestyle, and never looked back. He said, “I like catching fish. It’s fun.” There were times, though, when he was out in big seas and realized he was close to death. Despite dealing with dangerous conditions, as well as the constant stress of shortened openings and shrinking quotas, Mike, at age seventy-eight, continues to fish. It is, for him, a way of life. He is the last remaining commercial salmon fisherman living in Ucluelet; seeing him enter the harbour in his stately troller, the Blue Eagle, is always a sight for sore eyes.

Dan Edwards, member of a local fishing dynasty, started fishing with his father, Glen, at the age of seven. Although Dan spent four years working at surveying in logging, and three years at a fish camp, he had a forty-year career trolling for salmon. In later years, when trolling largely shut down, he switched to longlining, fishing for halibut, sable fish, dogfish and other species for the last twenty years before retiring. Dan’s son Ryan continues a fishing career in longlining and Dungeness crab fishing out of Prince Rupert.

Dan has been a strong advocate for the rights of west coast commercial fishermen through his work with many groups, including the Pacific Trollers Association, UFAWU (United Fishermen and Allied Workers’ Union) and the Canadian Council of Professional Fish Harvesters, of which he was vice-president. In October 2018, he was formally recognized by Nuu-chah-nulth leaders for “his dedication to…a more collaborative approach to stewarding fisheries.”40

Stormy Seas

Fishermen are a brave and hardy lot who love the solitude, the freedom and the wide horizons out at sea. The inherent dangers mean they do not always survive, and when they do, it is often by near misses.

George Saggers had a close call in 1931. There was a big sea running, but he was confident that once he got “around the outside” and into Alberni Canal, it would be smooth sailing. George didn’t get that far. Soon after leaving Ucluelet Harbour, he felt his boat, the Luceland, slow down, and he headed below to find the engine room a mass of flames. Unable to extinguish the fire, George abandoned ship in a skiff, managing to reach shore through “big swells and in the sweep of the strong gale.”41 Ucluelet residents saw the smoke and found George sheltering on shore, but the Luceland was a total loss.

George had his turn at rescuing others. On one occasion, Bob Kimoto’s troller, the Elina K (named after daughters Ellen and Nina), started taking on water near Pachena. Bob was a strong swimmer. He pulled the hatch cover off and used it as extra flotation to reach Pachena Beach. There, he spent three days, subsisting on seaweed and shellfish. His daughter Ellen said her dad stripped down to his yellow underwear, thinking it would make him more visible to potential rescuers. George Saggers was going by in his troller, caught sight of the brightly attired Bob waving from the beach, and rescued him. Every Christmas from then on, Bob gave George a bottle of rum. George didn’t drink, but the rum was always enjoyed by Christmas-time guests.

A week or so after Bob made it home, a local towboat operator contacted him and said, “How about I help try to raise your boat?” They succeeded; Bob’s troller was rebuilt, and by next season he was back out fishing aboard the Elina K.

Commercial fishers often travelled together, looking out for each other. Axel Tomren was glad of the company one January day in 1964. A violent storm whipped up on Barkley Sound, and Axel’s eleven-metre troller, the Karen A, turned turtle in twelve-metre waves and sank like a rock. Axel later said he experienced “the wildest swim of his life,” adding: “I just knew I wasn’t going to give up without a fight.”42 Luckily, he was travelling with his friend Glen Edwards, who turned back in 128-kilometre-per-hour winds and came alongside Axel. Just then, a wave lifted Axel up and he “half swam on board. It was like it had been rehearsed.”43 Glen pulled him to safety aboard the Wanderer II and they carried on for shelter.

The Karen A was not retrievable, and Axel, who had started commercial fishing at the age of fifteen, was soon out buying his next troller. “I might take a week off,” he said, “but fishing is my living.”44

Frank Hillier told me of a foreshadowing of the sinking of the Karen A. In the early 1950s, a group of “Ucluelet lads” made a pre-Christmas trip to Port Alberni to buy presents and liquor for the upcoming festivities. Aboard the Karen A were Axel and his brother Oscar, Frank, Bert Clark, D’Arcy Thompson and Ronnie Wesnedge. As they headed home through the Broken Group on December 23, the weather turned sour, so they turned around to seek shelter. When Axel executed the turn, the boat did a prolonged, disconcerting roll, startling them all. Regarding the Karen A’s demise in 1964, Frank said that in hindsight the earlier trip home from Port Alberni aboard the Karen A could have become a sad Christmas story for a group of Ucluelet families.45

When I asked Glen Edwards’s wife, Joey, if she worried a lot when Glen was out fishing, she responded: “Well, I’ll put it this way. You never let your guard down.”46

Fisheries Management

Management of the fisheries on Vancouver Island’s west coast has been complicated and contentious, going back many years. The Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) was established in 1868. In 1878, the control of federal fisheries was extended to BC, and the first regulations were imposed on BC fisheries. Since that time, to the frustration of many BC commercial fishermen, the federal government continues to oversee the West Coast fisheries.

In 1969, the federal government implemented the Davis Plan, licensing boats rather than fishermen. Many saw this policy as a move to hand the BC fisheries over to large corporations. Coastal fishermen decried the removal of fishing areas and privileges. The Mifflin Plan of 1996, officially known as the Pacific Salmon Revitalization Strategy, focused on cutting back the size of the BC salmon fleet, citing the need to address declining salmon stocks. Angry fishermen rallied in protest, in some cases publicly burning the new licence applications. Mike Smith described the program as another failed bureaucratic exercise. Dan Edwards added that it was “a constant battle to stay alive on the water.”

When salmon quotas were transferred to the sport fisheries, and when more quotas were lost in a 2008 agreement with the Americans, Canada’s West Coast fishermen received no compensation.

In 1999, a collapse of the Fraser River sockeye devastated the commercial fishery. Dan Edwards went on a hunger strike aboard the Silver Spray I in Vancouver’s False Creek, to pressure the government to negotiate some emergency relief for struggling fishermen. Promised a review of consultative process for fisheries, Dan ended the hunger strike after fifty-nine days. Ultimately, the government excluded coastal communities’ input, making the process even less effective than before.

Thornton Creek Fish Hatchery

The Thornton Creek Hatchery started up in the 1970s, with dedicated volunteers initially organized by Lowell Panton. The hatchery officially opened in 1981, with Julie Edwards as manager and Jean Duckmanton as assistant. Richard Smith later managed the hatchery for many years. When Richard retired, his brother-in-law Ray Bisaro took over for a year and a half, followed by Dave Hurwitz.

Volunteers serve on the society board. Historically, others also helped out when many hands were needed—for example, when moving large numbers of fish to different sites.

The Thornton Creek Hatchery is based on the model of Hokkaido, Japan, which has many successful small, community-based hatcheries. It is one of twenty-one CED (Community Economic Development) hatcheries in BC under the umbrella of the DFO. The Ucluelet and Toquaht First Nations are part of the Thornton Creek Enhancement Society.

The Three Amigos, like many other fishermen, devoted time and energy to the hatchery. As well as being a dedicated board member for years, Doug Kimoto also volunteered for thirty-one years as the PIP (Public Involvement Program) co-ordinator. PIP came under the DFO’s Salmonid Enhancement Program. Fisheries funded the cost of spawning gravel and equipment. Doug placed the gravel in salmon streams around the Kennedy Flats Watershed, “an area ravaged by unsustainable industrial forestry practises.”47 Doug received no pay and covered his own gas costs. “He really wanted to bring the fish back, you know?” Thornton Creek Hatchery manager Richard Smith said. “He worked endlessly.”48

Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy

The First Nations, who for millennia sustainably harvested fish from the West Coast waters, had to fight hard for their inherent rights. Finally, in 1990, a Supreme Court ruling known as the Sparrow Decision found that “the aboriginal right to fish for food, society or ceremonial purposes was a communal right…protected by the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.”49 In 1992, as a result of this finding, the federal government inaugurated the Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy, providing a framework for managing Indigenous fishing in a manner consistent with the Sparrow Decision.

In some cases, licences and quotas have been purchased by the government and then converted to communal commercial licences for First Nations communities. This has seen some support, from both Indigenous and non-Indigenous general fishery permit holders, as an opportunity to return some inherent rights in a spirit of reconciliation.

Sea Serpent Sightings

West Coast First Nations Oral History has long included sea serpent stories. The creatures are also depicted in carvings, beading, woven baskets and the petroglyphs that adorn Vancouver Island cliffs.

One of the earliest newspaper references to West Coast sea serpents was in an issue of the Victoria Daily Colonist, dated January 1, 1911: “From the WCVI [west coast of Vancouver Island], that last stamping ground of romance of the furthest West…the home of many quaint things comes a story of a sea-serpent. Of course no self-respecting mariner likes to tell of sea-serpents for the unbelievers of the cities sniff and suggest that the seeing of great snakes comes only from overindulgence in strong water.”

In the 1930s and ’40s, there were sightings along the island’s western coast, and people began to wonder if “Caddy” had taken some excursions from his favourite haunt. “Caddy” (full name: Cadborosaurus) was alleged to be a sea monster, most often seen along Victoria’s waterfront, especially near Cadboro Bay.

Reports of some sightings in Barkley Sound came from well-known Ucluelet fishermen, deemed credible witnesses with many years of experience at sea. A Province newspaper article described the sighting of a creature that looked like “a mammoth worm measuring a good hundred feet.”50 Thomas Taylor was on his way back to Ucluelet Harbour in May 1935 when he saw what at first appeared to be a large whale. As a sometime whaler, he soon decided the creature’s antics “were un-whale like in the extreme.”51 Slowing to half-speed, Tom moved in close to the creature, which he described in nautical terms as “about 100 feet long and six feet in circumference amidships, tapering towards bow and stern.” As Tom moved in for a closer view, “the monster surprised him by arching its back and raising its head after the manner of a snake.” Looking up at the head now towering above him at an estimated six metres, he decided to “cut his observations short and get along to port.” Heading away, he looked back to see the creature swimming off in a “leisurely fashion…although he judged by its lines that it was capable of high speeds if necessary.”52

The reporter concluded that “when such a respected citizen as Mr. Taylor returns home from the banks and relates his experience, there seems to be little doubt that such a creature does exist.”53

The following month, the Province printed a tongue-in-cheek article, recounting that “the sea-serpent that reared its whiskered head out of the depths near Ucluelet has drawn a good deal of comment. It pains us to discover that a few scoffers doubt even the existence of the worm, and for a correspondent to send us what might be called a sea-serpent saga is like twisting the knife in the wound.”54

In 1947, another well-known Ucluelet fisherman shared his sea serpent encounter in a sworn statement. George Saggers recounted being aboard his troller, the Thoroughbuilt, fishing on the southwest bank about five kilometres off Ucluelet. “Suddenly…a sort of shiver went up and down my spine.”55 He turned to a sight he’d never thought possible in all his twenty-eight years of fishing. George was being watched by a pair of jet-black eyes protruding “like a couple of buns” from a creature’s head.56 The brownish-grey neck and head rose about a metre out of the water. The back of the head had a mane, similar to a horse or lion, but he didn’t know “whether the mane consisted of carbuncles or hair.” George said the unreal-looking creature slipped back under the surface with scarcely a ripple. He concluded: “I would like to know what was under the water, although I wouldn’t like to be any closer or see it ever again.”57

The Colonist newspaper article further noted that despite a considerable groundswell, the creature was not affected, “meaning that like an iceberg, there was plenty of it under water!”58

More sightings soon followed. A 1947 article entitled “It’s the Season for Seeing Things” recounted Alberni flying saucer sightings along with sea serpent updates: “As for the serpent, they’re even trying to lasso it off the west coast near Ucluelet.” R. Meyers reported seeing the serpent while trolling at daybreak in his boat, the Dorothy, and said a Japanese fisherman chased it for miles, trying to rope it.59

The reported sightings reminded retired fisherman Dan McPherson that he had seen the monster in a channel near Ucluelet in 1920. He described getting his boat, the Beryl, close to the creature: “It had a head like a sheep or a camel and large grey eyes with tufts of hair underneath them, short ears and a neck eight or nine inches in diameter. Its color was similar to that of a Jersey cow.”60

In 1948, George Saggers was back in the news, having “again seen a sea serpent…This time it was looking in the opposite direction, but he had a better look at the body, which was long and seemed to undulate with the waves.”61

Dr. Albert Tester from the Pacific Biological Station at Nanaimo examined the skeleton of a purported sea serpent found in Barkley Sound in 1947 and concluded it was that of a gigantic basking shark. Respected West Coast historian George Nicholson was also not a believer. He suggested the so-called sea serpents were either a solitary hair seal or sea lion, a water-logged snag bobbing out of the water, or (what he considered most likely) a harem of undulating sea lions following a bull sea lion.

Sightings continued.

In 1980, John Gleeson reported seeing a gigantic sea creature while he was many kilometres off the western coast, aboard a naval supply ship. When Gleeson rushed to the bridge to ask if anyone else had seen the monster, he encountered blank stares. Later, Leading Seaman Landry assured him that “everyone who went to sea had encountered something that would never show up in a textbook or on a National Geographic special.”62 Gleeson later stated: “It seemed ancient to me at the time. I wonder if it’s still out there.” (I sometimes wonder the same thing when I head out of the inlet in my kayak.)

Not Just Another Fish Story

When researching sea serpent sightings, I was charmed to find this little 1935 newspaper article about my uncle:

"Same Halibut Hooked Twice: A True Fish Story

Ucluelet, where the latest sea serpent was sighted no long time ago, redeems itself with a fish story which, says the West Coast Advocate, is strictly true.

Arthur Baird was trolling for salmon, when, states the Advocate, he was surprised, on hauling in his line, to find, not the expected spring salmon, but a very large halibut. Since he was rigged for salmon, Mr. Baird could not understand the occurrence, but examination showed that his hook had fouled another, an old Indian-wrought halibut hook, on the fish’s head.

Undoubtedly this fish had been hooked years ago, and had escaped, only to be trapped again after years of freedom, when the original barb was almost worn away. The halibut was sold to the local buyer, but the old hook is being kept as a souvenir.63

"

Two years later, Uncle Art was back in the news when he hooked another big halibut while trolling for salmon. This halibut weighed ninety-four kilos, quite a size to land on a hand line. It sold for over fifteen dollars.64

A Changing Seascape

Ucluelet was once the third largest fishing port in BC. Up to ten fish plants bustled with activity around the harbour. All that has changed. As I sat talking to Dan and Mike in my living room in August 2024, we saw a steady stream of sport fishermen heading out to fish for salmon. They would have been fishing for a month by the time Mike Smith got government permission to go trolling. It is extremely sad but not surprising that he was then Ucluelet’s last commercial salmon fisherman.

In the summer of 2024, BC showed interest in transitioning to an owner-operator system, as part of its Coastal Marine Strategy. Dan Edwards had worked towards this over a ten-year period in meetings in Ottawa. It was achieved for the East Coast. Here on the West Coast, Dan worried that “it’s too little too late.” He asked, “Who are these owner-operators that they are going to support here?” because most of them have already been wiped out and few connections remain. BC seems serious about engaging but has a limited history of dealing with fisheries. Perhaps, says Dan, if they go about it right, there is potential for future generations to get back into fishing.