Chapter 3: Arrival of the Uninvited

Spanish explorers arrived on the west coast of Vancouver Island in the 1770s, and other Europeans soon followed. European contact had a catastrophic effect on the thriving Indigenous Peoples.

The new arrivals came with a history of depleting the environment. They soon discovered the beauty of, and market demand for, the sea otter. The Europeans acquired the glossy pelts from the First Nations, in trade for tobacco, metal tools, blankets, trading beads, firearms, copper sheeting for artwork and alcohol. The mutual trade purportedly began amicably, but disagreements soon led to skirmishes and violence.

As the global market increased, the European traders’ greed caused near extinction of the sea otter. The focus then turned to gold. The 1858 Fraser River gold rush drew thousands of prospectors to BC, many of them arriving in coastal ports. They brought disease, including measles, typhus, cholera, tuberculosis, sexually transmitted infections and smallpox. The Indigenous Peoples had no immunity to these diseases. The most virulent, smallpox, decimated a large percentage of the population.

In 1866, the Crown colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, which had been formed with no acknowledgement of the First Nations people who had lived here for millennia, joined together. In 1871, they joined Confederation to access the railway. Colonialism was rampant, with settlers taking land under the umbrella of the Canadian government.

In 1876, the federal government created the Indian Act, declaring the First Nations people to be wards of the state. The government seized most of their land, putting them on reserves managed under the Indian Act. The amount of land allocated was a small fraction of the Traditional Territory of the First Nations. Then, at the whim of the government, these tracts of land could be made even smaller. Joseph Trutch, now decried for his racist attitudes and unjust actions, was the first Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia. A civil engineer and land surveyor, he refused to accept the reserve sizes established by former governor James Douglas, cutting them by 91 percent. Trutch has been strongly criticized for his anti-Indigenous policies. As of the early 2020s, some streets, avenues and buildings in BC have been stripped of his name and replaced by First Nations names.

In 1914, the Royal Commission on Indian Affairs travelled aboard the CPR steamship Tees along the West Coast region to inspect reserves. The commission group of five individuals included three federal and two provincial representatives. Indian agent Gus Cox of Alberni accompanied them, with no First Nations representatives. What then became known as the McKenna-McBride Commission made heavy-handed decisions without consulting any First Nations people. Hundreds of acres were cut from reserve lands because they were valuable for timber rights. The First Nations were forbidden, under the Indian Act, to harvest trees on their land.

Indian Agents

From the 1830s to the 1960s, so-called Indian agents were hired by the Canadian government to oversee what happened on reserves.

When the Indian Act was established in 1876, Indian agents were given more power on-reserve. Their rule enforcement included a pass system, controlling the movement of First Nations people off-reserve.

Although both Charles Stuart and Eddy Banfield have been listed as early Indian agents, records state that the first Indian agent on the West Coast (and also the first in BC) was Harry Guillod.

In 1866, Harry, who came from the British aristocracy, was a lay teacher and missionary for the Anglican Church. The bishop first sent him to the Alberni region with Rev. Julius Xavier Willemar, a former Catholic priest originally from France. They made numerous visits there, by canoe and then by foot along mountainous trails, and after four weeks began preaching the gospel.

Church and school instructions were given in the Chinook jargon, a dialect used between the Indigenous Peoples and the European traders in the Pacific Northwest. School attendance dropped when visitors from other nations presciently warned some of the boys that “if their names continued on the school-books it would cause their death.”1 Willemar and Guillod transferred to Comox, complaining they were not meeting enough Indigenous people in Alberni to pursue their missionary goals.

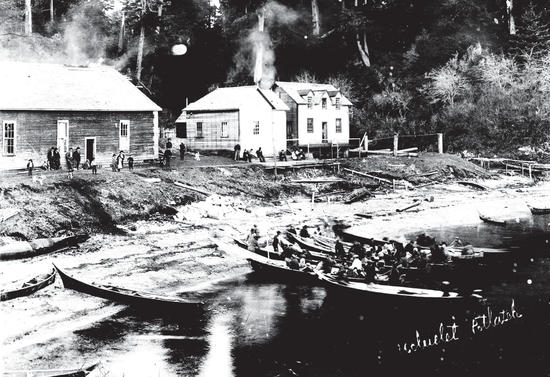

Harry Guillod was appointed West Coast Indian agent in March 1881, with a yearly salary of $1,200. In 1885, he married Kate Munro of Victoria. They moved to Ucluelet, where a house had been built for them on the east side of the harbour. In one of his first reports, he lobbied for the West Coast Agency to be based in the more central location of Ucluelet (which he writes with two suggested spellings: “Uthulhlet” and “Euclulet”), rather than in Alberni.2

Guillod kept detailed records, which help show changes affecting the First Nations people during his years on the West Coast. His job required him to cover a huge area. Every summer, he travelled by canoe between Port Renfrew and Quatsino Sound, stopping at all the villages and settlements along the coast. He kept a census and dealt with complaints and disagreements. He also helped with medical issues, at one point vaccinating over two hundred individuals during a smallpox outbreak.3 Guillod reported the prevalence of whooping cough and measles, and referred to “the great want of simple medical attendance in most of the tribes, as my Agency is so scattered that I cannot look after them properly in this respect.”4 He also reported “advising the Indians to take proper care of their children in case of sickness”5 and voiced no acknowledgment that, were it not for the colonial presence, these sicknesses would not be prevalent.

Regarding treatment of the Indigenous people, Guillod stated in one report: “The actions of the provincial government appear to be very short sighted…their present actions seem to indicate a total disregard to Indian rights, which must sooner or later bring trouble on the province.”

Guillod’s job included allocating Department of Indian Affairs rations. Again, there was no awareness that the First Nations people had been effectively feeding themselves with their preferred nature-based diet before the colonial appearance with far less healthy food.

Harry and Kate Guillod and their three daughters remained in Ucluelet for four years, and then relocated to Alberni after Harry cited hardships of life in Ucluelet and the need for his children to attend school. They built on River Road, and their small home also served as the Indian agent office.

Residential Schools

The residential school system dates back to the 1840s, and was a network of boarding schools for Indigenous children funded by the federal government and run by the churches. Initially a voluntary plan, it was soon made mandatory—Indigenous parents who did not send their children to the schools were treated as criminals, sometimes being arrested, charged and jailed, and their children forcibly removed. Vi Mundy of the Ucluelet First Nation said, in a 2022 Maa-nulth Treaty documentary, that traditionally “the community raised the children” and everyone looked out for each other.6 When children were taken from their families, entire communities were torn apart.

In residential school, the children were forced to learn English and punished if they spoke their own language. Ucluelet Elder Art Cootes said that one of the most powerful words in his culture was “respect,” and that was damaged when residential schools caused disconnection. The children did not know how to relate to their parents and their culture when they returned home. “They showed us how not to be Native. They separated us from our parents for that reason. So they could take the Native out of us, our cultural ways, all our values.”7

Through the 1920s and ’30s, the government sought to expand the residential school system. In 1920, Duncan Campbell Scott, who worked for the Department of Indian Affairs for fifty years, stated: “The happiest future for the Indian race is their absorption into the general population, and this is the object of the policy of our government.”8 This abhorrent policy has now been labelled cultural genocide.

Many children from Ucluelet attended the Alberni Residential School. It burned down in 1919, was rebuilt, and then was destroyed by fire a second time in 1937. The Department of Indian Affairs proposed rebuilding it in Ucluelet, but the United Church insisted it be in Alberni. Earl Mundy of hitac̓u told me he was “kicked out” of the Alberni Residential School as a young boy in the 1940s, after being there for a year and a half, because sticking up for his rights was considered bad behaviour. He suffered all his life from pains in his hands caused by repeated blows from a wooden yardstick. Earl said he was happy to return home to hitac̓u and that he was treated much better at the day school there.9 In later years, he embraced his culture, taking on his role as Hereditary Chief of the Tseshaht First Nation.

Banning of the Potlatch

The word “Potlatch” is from the Chinook word “ patshatl,” meaning “giving.” A ceremonial event traditional to First Nations of the Northwest Coast, it includes feasting, speeches, singing, dancing, storytelling and the distribution of gifts to the attendees. Potlatches often mark special occasions such as a marriage, birth, death, bestowing of a name or passing-down of a Chieftainship. These events are an important connection between Clans and nations, and a statement of honour and acknowledgement.

Laws were often discussed and validated at a Potlatch, and the Chief who held the gathering exhibited his established place in the hierarchy. The European arrivals could not understand the Potlatch. They came from a society of showing wealth by accumulating as much as possible. At a Potlatch, the Chief’s giving of gifts emphasized his generosity, wealth and power. The recipients were considered beholden to the Chief, and visiting Chiefs would in turn work at accumulating more wealth so they could hold their own Potlatch and give even greater gifts. The guests were not supposed to decline the gifts.

In 1884, the Canadian government banned Potlatches in an amendment to the 1876 Indian Act. The ban came into effect in 1885, with the government decrying Potlatches as pagan, wasteful and immoral. It became a criminal offence to hold or attend a Potlatch. This ban was not easily enforced on the west coast of Vancouver Island, where Harry Guillod noted widespread resistance by local First Nations. Guillod disagreed with the government’s stance that Potlatches were wasteful, reporting that “all carry away what they cannot eat.”10 Many west coast traders also did not want Potlatches banned, as the First Nations bought numerous items to give away to attendees.

The banning of Potlatches fit with the government agenda to assimilate the First Nations. As Bob Joseph explains in 21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act, “Almost three generations grew up deprived of the cultural fabric of their ancestors.”11

In 1951, the ban was lifted. By then, much damage had been done. Many significant cultural items were stolen by colonialists, which was disastrous to a society whose culture depends greatly on the passing down of names, songs, dances and stories, and also of artwork created with traditional designs.

This happened not only at Potlatches, but on a much wider scale. Treasured items were either stolen or “bought” for a minor token. In 1893, Harry Guillod collected First Nations cultural materials to send to the Chicago World’s Fair.12

A Victoria newspaper reported in 1900 that individuals from a Chicago museum and the museum of the University of Pennsylvania were “touring the Pacific Coast collecting Indian curios for their respective museums.”13 Anthropologist Franz Boas, US Navy explorers Albert Niblack and George Emmons, and others provided the taken artwork to collectors worldwide. British botanist and ethnographic researcher C.F. Newcombe put together a massive collection at the provincial museum in Victoria.

Such expropriation, by individuals and by institutions, had a devastating impact on First Nations cultures. As of today, taken items are gradually being returned to their rightful places, but it is a long, slow process.

Moving Forward

Surviving the catastrophic effects of colonialism has required strength and resilience on the part of Indigenous Peoples. In 1983, the modern treaty process began with lengthy negotiations between First Nations, British Columbia and Canada. In 2001, when the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council agreed on a treaty proposal in principle, six nations rejected it. Five others, including Ucluelet and Toquaht First Nations, formed a group in 2004 called the Maa-nulth First Nations, meaning “villages along the coast.” The Maa-nulth group approached the BC and Canadian governments for further negotiation, and the resultant treaty was ratified in 2009. The Maa-nulth Treaty took effect on April 1, 2011.

Vi Mundy, then Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ elected Chief, worked hard on the treaty process and said she cried when it was signed. Her husband Bob Mundy’s first reaction was surprise, and he stated: “We did it. Long days, long weeks, long years.”14 Anne Mack, Hereditary Chief of the t̓uk̓ʷaaʔatḥ, described how hard it was during treaty negotiations to see her father, then Chief Bert Mack, asking the Canadian government for land that was rightfully already Toquaht land. She went on to express how good it felt to reclaim large portions of their land, and to move forward.15

With the treaty signing came the challenge of implementation and adjustments. The t̓uk̓ʷaaʔatḥ now has water plants and a water treatment program for three hundred homes at m̓aʔaquuʔa (Macoah). The nation runs businesses such as the Secret Beach Campground and Kayak Launch, and the Toquaht Forestry Company, which has a timber mill and sawmill.

Ucluelet First Nation initiatives include Wya Point Resort, a campground and bike tour and rental business at the Ucluelet–Port Alberni highway junction, Thornton Motel in Ucluelet, and a logging enterprise.

The Ucluelet First Nation website documents that one of their mandates is “to promote education and community programs that enhance Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ and Nuu-chah-nulth identity.” This is done in a variety of ways. One significant step was the building of a “mini big house” at Hitacu. This traditional cedar structure provides a cultural and healing space. At the inaugural walk-through and song celebration for the building in 2021, Elder Marjorie Touchie spoke about its significance, saying it brought back childhood memories of being in a traditional big house. She said it was impossible to describe to children what it was really like, but now they would be able to experience it themselves: “The sense of feeling…like the safety and the teaching…The complete love and respect that we got in those rooms from the elders.”16 The design fronting the house is by artist Jackelyn Williams, who grew up in Hitacu. Her design incorporates a Thunderbird on a whale hunt, as well as a wolf, and depicts powerfulness, wellness, prosperity and connection to the land. The artist stated that the building helps signify that their history is still relevant, and spoke of the connectedness one may feel when entering such sacred spaces.17

Traditional teachings are an important part of cultural revival. In 2014, the Warrior Program for young men was formed in Hitacu, under the leadership of Jay Millar and Ray Haipee. Debbie Mundy was instrumental in bringing the practical learning model to Hitacu. This program focuses on instilling respect, responsibility and discipline, and incorporates learning traditional skills. James Walton, who took over leadership of the group, described it as a safe place to grow and heal.

A Warriors group for young women, girls and Two-Spirited People was subsequently formed, and also focuses on cultural practices.

In 2018, Tla-o-qui-aht master carver Joe Martin led a team of seven, including Ucluelet First Nation citizens, in the creation of a ten-metre cedar canoe at Hitacu. Joe Martin stated he was there to teach, and that “carving a canoe is actually a service to our culture.”18

The completed canoe was shared with the Hitacu community in 2019, during culture week, and President Chuck McCarthy did the official cutting of a woven cedar ribbon. Many events continue to take place at both Hitacu and Macoah, nurturing and reviving the culture.

Language Preservation and Revitalization

Both Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ (Ucluelet First Nation) and t̓uk̓ʷaaʔatḥ (Toquaht First Nation) speak the West Barkley dialect, and much work continues to revive and preserve the language.

One of the many destructive results of residential schools was the near eradication of Indigenous languages. Anthropologist Edward Sapir visited the Ucluelet area in the early 1920s to study their dialect, calling it one of the “Aht” languages. In 1949, Morris Swadesh, who worked with Sapir, visited respected Elder Charles McCarthy at Hitacu and presented him with a phonetically based book published in 1939 by Sapir and Swadesh called Nootka Texts, based on material learned from First Nations people of the Barkley Sound area.

Barbara Touchie was a strong force in preserving the Barkley dialect. Her father was from Toquaht and her mother Ucluelet. Barbara was born in 1931 and grew up in a home where no English was spoken, and their language was very much alive. When Barbara married Samuel Touchie, Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ Territory became her home.

Barbara worked with several linguists in the 1990s to create a written language for their spoken one. This led to an alphabet consisting of forty-four letters and symbols. Barbara’s daughter Vi Mundy recalled that her mother did not use a word processor, but instead wrote everything out, sometimes on paper napkins. Vi then typed out her mother’s materials. A German friend, anthropologist Henry Kammler, worked with Barbara on creating a dictionary. Others contributing to the language preservation include Marge Touchie and Dr. Bernice Touchie. Vi Mundy explained that their language is a “living language” because new words are sometimes created for items (for example, a refrigerator) for which they originally had no word.

Elders who spoke the West Barkley dialect and shared their knowledge included Rose Cootes (née McCarthy), Sarah Tutube and Louise Roberts, wife of former Hereditary Chief Wilson Roberts. Bob Mundy, husband of Barbara Touchie’s eldest daughter Vi, also shared knowledge of the language, partly by mentoring youth. Although Bob attended the day school at Ucluelet East, where the students had to speak English, his mother Gertie spoke only the First Nations language at home. Bob was an only child, and he has theorized that he retained the language because he spent so much time with his mother. When Bob passed away in 2024, he was one of the few remaining Elders who spoke the language. Vi, who passed away the same year, had co-ordinated language learning opportunities.

Barbara Touchie, mother of fifteen children, left a great legacy of extended family. Some say she handed the torch on to the younger generation. Two of her granddaughters, Samantha and Jeneva, work at speaking and writing the language. Samantha has translated children’s books into the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ language. On a Zoom workshop, Jeneva said: “Our language is history that enables us to connect to our ancestors and guides us in our futures.”19 The work continues through the dedication and motivation of Barb’s grandchildren and others.

The Toquaht Nation’s Language Program, under the leadership of language/culture co-ordinator Gale Johnsen, also promotes learning and preservation. Significant progress continues to be made, including the development of a Language Learning website, and the writing and production of eight children’s books.

A young man who has been a driving force behind the preservation of the nuučaan̓uł language is Timmy Masso. Timmy is a member of the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation and a resident of Ucluelet. His passion for the language started early; in Grade Four, he took a university-level language class, followed by another in Grade Five. In Grade Eight, Timmy gained permission to teach the nuučaan̓uł language to his classmates.

In 2016, his impromptu speech to the Assembly of First Nations meeting in Victoria helped spark the Nuu-chah-nulth Language Proficiency Certificate program. Despite his young age, Timmy graduated from the inaugural program offered by North Island College in Port Alberni. This qualified him to be a teaching assistant for Nuu-chah-nulth classes at west coast schools. After graduating from Ucluelet Secondary School in 2021, he went on to earn a teaching degree by age nineteen, and continues to work to preserve the Nuu-chah-nulth language.

Repatriation of Treasured Belongings

There was much cause for celebration when, in 2020, taken artifacts came home to Hitacu. Citizens and Elders of the community gathered as a truck appeared out of dense morning fog, transporting items being returned from the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec. Jeneva Touchie offered a welcoming prayer. This repatriation event followed a long process requiring considerable patience and hard work from Samantha Touchie, with support from Carey Cunneyworth, the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ government’s director of culture and heritage. The initial shipment of thirteen items was followed the next year by sixteen more, welcomed by the community and a drumming prayer from Lindsay McCarthy.

Neighbouring Communities

In and around the village of Ucluelet, steps are being taken to share the history of the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ. Signage at Terrace Beach relates how it was used as a safe landing and storage space for large ocean-going canoes. Below an Elder tree on the Spring Cove Trail, a sign pays homage to Barbara Touchie and family, “celebrating the partnerships that continue to enhance understanding of traditional wisdom.” And in front of the former Chamber of Commerce office, an unfinished dugout canoe was displayed, with a sign describing how the canoe was carved more than two hundred years before. The canoe was on loan to the District of Ucluelet, and arrangements were made in the summer of 2023 to relocate it to hitac̓u, because of its high cultural importance.

On October 13, 2020, Ucluelet First Nation President Charles McCarthy presented Mayor Mayco Noel and the Council of the District of Ucluelet with the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ flag. As President McCarthy explained, the flag represents the independence of the Ucluelet First Nation, and the flag-raising ceremony demonstrated the positive relationship between the two neighbouring communities.

July 2022 saw new street signs bearing Nuu-chah-nulth and English names unveiled in Ucluelet. Jeneva Touchie explained that “only nouns that are familiar to who we are and where we live can be translated.”20 Roughly half of existing street names in Ucluelet were then nouns, and were to be updated with new bilingual signage. Nuu-chah-nulth signs can also be found in the Ucluelet Co-op and in Ucluelet schools.

Education

A key component of moving forward includes education. On September 30, 2023, Canada’s National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, I attended a presentation at Ucluelet Secondary School. As I walked through the halls of the newly renovated school, I reflected on my experience as a student there in the 1960s. When I attended, the Canadian history curriculum did not address the damaging practices and effects of colonialism. This omission was a huge loss for the entire school population and must have been especially galling to my First Nations fellow students.

Later, when I worked in the elementary school and then the high school, from the mid-1980s on, changes were under way. Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council education worker Linda Marshall taught the students beading and cedar weaving. Barbara Touchie visited classes regularly to teach the local Nuu-chah-nulth language.

More progress happened when Ucluelet Secondary School staff member Karen Severinson proposed the carving of a totem pole. This was done as a learning project under the tutelage of master carver Clifford George. Much of the work was done by then student Hjalmer Wenstob, who is now a celebrated Nuu-chah-nulth artist with a gallery workshop on the Ucluelet waterfront. In June 2010, the pole was raised with celebration and pride in front of the school. When the new secondary school was built, the pole was relocated near the front doorway. At the grand unveiling, Hjalmer Wenstob explained its significance on behalf of Clifford George. First Nations art on the doors and windows of the new school was created by artist and former Ucluelet Secondary School student Jackelyn Williams, in collaboration with Elder Rose Wilson.

Youth-led reconciliation projects displayed at the school on National Truth and Reconciliation Day are inspiring. Guided by innovative teachers, students write original and empathetic poetry, design and print original T-shirts focusing on reconciliation and healing, and create projects on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s ninety-four Calls to Action, investigating the progress of implementation. The school partners with the Clayoquot Biosphere Trust and the Legacy of Hope Foundation. Jason Sam, the trust’s program co-ordinator, is “consistently impressed with the reverence the students give to the subject.”21

The BC Ministry of Education took a step forward by making it mandatory for students to complete at least four credits of Indigenous-focused coursework for high school graduation. This initiative, the first in Canada, was implemented for students graduating in the 2023–24 school year.

As conversations on truth and reconciliation continue, the need to heal remains. As a descendant of settlers, it is not my right to assess the present standing of reconciliation. I write with an attitude of respect for First Nations, and an awareness that I do not have their perspective. I will continue to educate myself. Tla-o-qui-aht Elder Dr. Barney Williams, a renowned healer and therapist, emphasizes that all people should listen and take what they hear to heart.22