Chapter 13: Boats, Planes and the Long-awaited Road

The first boats used for transportation up and down the coast were dugout canoes, seaworthy vessels carved from single trees. The First Nations were masters at building these canoes and travelled great distances in all kinds of weather. Early settlers arriving on small sailing schooners noted the reliability of dugout canoes and used them for transport.

Long-time Ucluelet resident Pete Hillier recalled that when he was young, a dugout canoe could be bought for ten dollars. “You don’t see any of the dugout war canoes like there used to be,” he added. “I can remember when I was about eight or nine riding on one of the canoes, the sides of the boat were so high I couldn’t reach the gunwhales.”1 The settlers often travelled long stretches of coastline by canoe or rowboat.

In those early days, the sea was the highway. As a 1914 newspaper worded it: “Of all conveyances but boats, the West Coast is still chary, but of boats, and of men who go down to the sea in ships the number is legion, and the man who has a fast and safe seacraft, is rated high among his associates.”2

The Coastal Steamers

The ships servicing the West Coast were a lifeline to all the small communities. They carried mail, supplies and passengers. They transported ore, canned salmon and lumber. They also delivered livestock—in June 1900, twenty-five sheep arrived in Ucluelet for west coast ranchers.3 A visitor from Victoria commented that “much interest was taken…in the landing of a donkey at Ucluelet, though for what purpose did not transpire.”4

Residents focused on the movements of the steamers up and down the coast, and arrivals were eagerly anticipated. Schedules had to be flexible, as weather conditions, tides and extra stops all affected arrival times. West coasters frequently watched sadly as a steamship passed them by because conditions were too rough for landing. The comings and goings were reported in the Colonist newspapers, in a form of “shipping news.” The first steamships were small and were gradually supplemented or replaced by larger steamers over the years.

The Maude, a converted sidewheeler, started the first west coast steamship run in 1887. Passengers boarded her with trepidation, having heard of “Maude fever,” an illness brought on by the smell of greasy food and engine oil combined with rolling ocean swells. The Willipa, considered a more reliable little freighter, began on the west coast route in 1898. By 1900, the route was shared by the Queen City, a steamer converted from a three-masted schooner.

In 1901, the Canadian Pacific Railway bought all the steamers owned by the Canadian Pacific Navigation Company, and by 1903 the Tees took over the west coast route, having arrived in Victoria from England via the Strait of Magellan in 1896. Captain Smith, skipper on the voyage, pronounced: “She rides the water like a duck.”5 Such praise was rare for the Tees. Sometimes referred to as a wallowing tub, the often disrespected vessel sat low in the water in rough seas. Even the most seasoned sailors succumbed to seasickness aboard the Tees, and she was dubbed “the Holy Roller.”

Captain Edward Gillam, a master mariner born around 1864 in Newfoundland, became a much-loved fixture along Vancouver Island’s west coast. After coming to Victoria at the age of sixteen, Gillam worked his way up from deckhand to skipper on the Queen City, before transferring to the Tees. Although she suffered many mishaps, Gillam consistently referred to the Tees as a staunch little vessel. He would soon take command of a new and mightier ship.

The Good Ship Maquinna

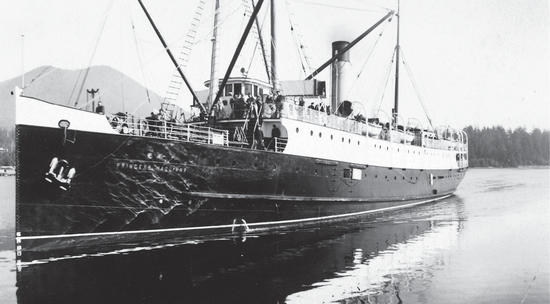

Captain James Troup, manager of the BC Coast Steamship Service as of 1901, instigated the building of a new fleet of ships to serve the coast of British Columbia. The Canadian Pacific Railway’s elegant and iconic “Empress” ocean vessels already traversed the Atlantic and the Pacific. Under Troup’s leadership, there would ultimately be a fleet of nineteen “Princess” ships. Troup helped design nine of these smaller ships, then lobbied for something bigger and better to serve Vancouver Island’s west coast. The CPR board of directors listened to him, and the Princess Maquinna was constructed.

She was built in Victoria at Bullen’s shipyard. With an overall length of 74 metres and a gross tonnage of 1,612 metric tonnes, she was then the largest steel vessel to be built in BC. Unique in style for the West Coast, she was named for the daughter of Chief Maquinna, a powerful Nuu-chah-nulth ruler.

The Daily Colonist chronicled progress during the building stages, predicting that “the arrival of Maquinna on the West Coast of Vancouver Island will prove an eye-opener to the towns on the Vancouver Island coast, as no vessel approaching the design and lines of the new craft has ever plied those waters.”6

The Maquinna was launched on Christmas Eve, 1912, gliding smoothly and gracefully into the water. Thus began her impressive thirty-nine-year career on the west coast of Vancouver Island. The Maquinna sailed from Victoria on her maiden voyage on the morning of Sunday, July 20, 1913, commanded by Captain Gillam. He was already closely connected to the ship—Troup had wisely sought his input on design and construction, aware that Gillam was well versed in the unique challenges presented by the dangerous west coast waters.

Cheering crowds welcomed the new ship at most stops along the coast. She arrived at Bamfield to the fanfare of a band playing aboard a gasoline launch festooned with waving flags. The residents of Port Alberni turned out en masse for the grand arrival, with music blaring and whistles blowing. She entered a more subdued Ucluelet Harbour, owing to her 4 a.m. arrival. However, “banners welcoming the steamer were stretched across the roadway and wharf, and every evidence of welcome to the new boat was displayed.”7

Captain Troup, aboard to experience the fulfillment of his vision, enthused about how well she handled rough weather. He also noted that many of the wharves on the route would need to be enlarged to accommodate the Maquinna. By November 1913, alterations to lengthen wharves at Ucluelet, Clayoquot and Quatsino were under way.8

Residents up and down the coast expectantly awaited her distinct arrival whistle—long-short-long-short. Author and historian R. Bruce Scott described the pitch as faltering on its last note: “Like a young boy’s voice, it always broke and ended in a high falsetto.”9

Passengers and crew enjoyed a new level of comfort. The Maquinna accommodated 104 first-class passengers, with ample room for second class as well. The mahogany-panelled dining room offered sumptuous meals. A smoking room was fitted out in hardwood. Passengers strolled the deck, played bridge and enjoyed music and dancing in the evenings. (That is, some of the passengers: sadly, in accordance with the prejudiced attitudes of the time, Indigenous people were forced to ride outside on the foredeck or in the cargo hold.)

Captain Gillam served as the ship’s skipper for her first sixteen years. He was a master at using the piercing whistle to navigate through fog along the dangerous coastline, gauging the nature of the whistle’s echo to pinpoint their location. His finely tuned ear was also noted in his musical ability. At gatherings when the Maquinna was moored at small outposts, Gillam performed dance music on his violin. He also played Santa Claus at Christmas, filling his cabin with so many gifts that it was a challenge for him to find space to sleep. As justice of the peace, Gillam officiated at on-board weddings. On occasion, he dealt with individuals charged with the illegal sale of alcohol, issuing fines or jail time.

The Maquinna earned the monikers “the Good Ship Maquinna” and “Old Reliable.” Her skippers and crewmen were reliable as well. Certified deep-sea sailors, they dealt with wild weather, heavy seas and a treacherous coastline.

The Princess Norah

As large numbers of enthusiastic travellers vied for passage on sightseeing cruises up the coast, Troup masterminded another princess for the fleet. The Princess Norah was built in 1928 by the Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company of Glasgow, Scotland. At seventy-six metres, she was slightly longer than the Maquinna but outweighed her by more than nine hundred tonnes.

The Princess Norah arrived from Scotland in 1929, starting on the route mainly to transport tourists. She was described as “a sleek and gracious beauty of a ship, a real Princess, with something new—a bow rudder to help her navigate the narrow passages and inlets of the rugged West Coast.”10 Captain Gillam skippered her maiden voyage up the coast in April 1929. Dignitaries aboard included the Governor General of Canada and his wife, Lord and Lady Willingdon, as well as the Honourable Robert Randolph Bruce, Lieutenant-Governor of BC. The ship’s deluxe accommodation provided ample room for Lady Willingdon’s lady-in-waiting and personal maid.

Much was made of the elegant appointment of the Princess Norah: “Why, in the dining room you actually found fingerbowls!”11 Whether Lady Willingdon acquired a fingerbowl or something similar from the Maquinna is not known, although she was said to have “taking ways…If she was visiting your house she would admire this, or that, and the owner was expected to present to her whatever it was she admired. Hostesses learned to put into hiding any object which they did not wish to lose when Lady Willingdon came to call.”12 She gave freely of her signature gifts in return, “handsome autographed photographs of the pair, in beautiful sterling silver frames, with the vice-regal crest on top.”13

On the inaugural trip, Lady Willingdon did daily one-and-a-half-kilometre walks around the deck and made frequent visits to the bridge, “where she literally stormed Captain Gillam with questions regarding the operation of the vessel.”14

Whereas the Maquinna’s maiden voyage had arrived in Ucluelet in the wee hours of the morning, the Princess Norah steamed up Ucluelet Harbour in broad daylight, allowing for a livelier welcome. The Colonist newspaper remarked that “the Norah was invaded by school children of three races” (Nuu-chah-nulth, Japanese Canadian and Caucasian) “who had been accorded a holiday for the occasion.”15

Captain Gillam skippered the new ship for just three weeks before passing away at the age of sixty-five. On May 3, 1929, in heavy seas off Tofino, he was injured in a fall down a companionway on the Princess Norah. Reasons for his fall were variously attributed to a heart attack, a dizzy spell and unfamiliarity with the ship’s layout. What is known is that he struck his head and succumbed to his injuries. After reaching Tofino, the Princess Norah completed the rest of her voyage northward, before returning to Victoria with the esteemed captain’s body.

A Farewell to “Old Reliable”

By 1952, big changes were happening on Vancouver Island’s west coast. Large fish packers transported fish. Some communities (although not yet Ucluelet) were accessed by roads, enabling freight truck transport. Many passengers chose to travel by plane rather than ship. Operating the Maquinna went from the black into the red. She needed repairs, and they were not financially viable.

Her second-to-last scheduled trip was slated for September 4, 1952. Cargo and passengers aboard, she cast off from the Belleville Street dock in Victoria at 12:17 a.m. Minutes later, her boilers gave out, unable to produce the required steam. She limped to a nearby dock. “Old Reliable” had finally worn out.

The ship’s bell was presented to clergyman Padre Leighton, who spent many hours aboard the Maquinna from 1930 to 1935, when he served in the West Coast Mission. He displayed the bell at the Mission to Seafarers in Vancouver until his retirement, then took it with him to Tofino. It is now housed in the Tofino branch of the Canadian Legion. The Maquinna’s binnacle was given to the Ucluelet Sea Scouts and is now displayed at the District Office, under the care of the Ucluelet and Area Historical Society.

With the Maquinna no longer in commission, and the Princess Norah withdrawn for an Alaska run two years earlier, the owners scrambled for a replacement. Their purchase of a refurbished US Army tender, renamed the Princess of Alberni, caused a hue and cry from west coasters who doubted her seaworthiness. By August 1958, she was sold, and was “renamed, as well as resexed” when new owners called her the Nootka Prince.16 Her “princely” stint lasted less than a year. Sold and converted to a tug, she retained her link to royalty with the new name Techno Crown. The Princess Norah had also been renamed the Queen of the North, then sold and renamed the Canadian Prince. The renaming and repurposing of the Princess Norah and the Princess of Alberni signalled the end of more than fifty years of service provided by the CPR to Ucluelet and other small communities up and down the outer coast.

Brothers Doug and Percy Stone (not related to Chet and Stuart) provided mail service in Barkley Sound for fifteen years with the Victory I and Victory II. When their mail contract expired in 1936, they had made 2,209 mail trips down the canal. The Stone brothers branched out into tugboating, adding many more Victory vessels to their thriving fleet.

The Uchuck I, II and III

Captain Richard Porritt, a former skipper for Doug and Percy Stone, took over their relinquished mail route with a BC Packers cannery tender. He named his ship the Uchuck, a nuučaan̓uł name meaning “quiet waters.” The Uchuck was “a smart little boat of about forty feet…always kept trim and clean.”17 Porritt transported mail, supplies and passengers to logging camps, canneries and fish plants, and visited Ucluelet, Tofino and Bamfield. In 1941, he launched the seventy-passenger Uchuck I in Vancouver.

In 1946, Porritt sold his Uchuck business to Henry Esson Young and George McCandless, who started a new enterprise, the Barkley Sound Transportation Company. The partners soon bought a second vessel, a ferry named the West Vancouver Number 6. Captain Richard McMinn, hired by them as skipper, was initially taken aback when he travelled to Vancouver to pick her up. “There was no more horrible ship on the west coast, in the state she was in…But we bought this old girl. She was a good ship, really; strongly built.”18 McMinn went on to say they met the Princess Maquinna on the return journey. “I could almost see the Princess Maquinna, my old ship, stagger at seeing this old ferry approaching Cape Beale.”19

The old ferry was reconstructed in Port Alberni and renamed the Uchuck II. Captain McMinn had his concerns about her. “She very often put her nose under a sea and took out a few tons of water. She occasionally worried us.”20

Travelling from Bamfield to Ucluelet can be rough, especially in winter. McMinn described the crossings as “hairy to say the least.” The Uchuck II carried fresh milk in twenty-gallon containers lashed to the forward bulwarks. “On many a trip when the heavy seas lifted a lid, the entire foredeck was awash in milk and cream. This run made no passenger happy.”21

With business growing for Barkley Sound Transportation, the search was on for another vessel for the fleet. In 1952, Esson Young found her in the neglected “hulk of a US Navy minesweeper” called the YMS-123. She was tied up in Vancouver, stripped clean of any useful equipment, right down to the light switches.

Alberni shipwright Bill Osborne declared her sound, the purchase was made and George McCandless towed “the sorry-looking wreck” from Vancouver to Port Alberni with the Uchuck I. He discovered, upon heading up the west coast, that he had to tow her stern-first to keep her following “more or less, in the wake of the Uchuck I.”22

The conversion of the derelict YMS-123 was lengthy and expensive but yielded a reliable vessel. She had strong bones, having been built “to withstand the shock from exploding mines that had been cut loose by its sweep gear and then detonated.”23

Once major reconstruction was finished, the overseeing engineer John Monrufet planned and laid out the engine room. In July 1955, the Uchuck III was complete. Owners Esson and George organized a celebratory run for all those involved in the rebuild, and the next day the Uchuck III began serving Barkley Sound residents.

When the long-awaited road finally connected Ucluelet and Tofino to Port Alberni, the Barkley Sound Transportation Company downscaled. The Uchuck III made her final sailing out of Ucluelet in 1960, with many residents on hand to wave farewell. The Uchuck II was relocated to the Gold River area.

The Uchuck III was chartered briefly to a captain at Alert Bay, then recalled to Port Alberni to do runs up to Nootka Sound. I was thrilled in 2019 to travel aboard her from Gold River to Friendly Cove, especially when the skipper allowed me some (supervised) time at the wheel.

The Lady Rose

Experienced seamen Dick McMinn and John Monrufet saw an opportunity when the Uchucks were pulled from the Ucluelet run. They started up Alberni Marine Transportation Ltd., briefly running the old Uchuck I, which they soon found “had suffered the ravages of time and now leaked like a sieve.”24 Needing a larger vessel, they acquired the Lady Rose.

The Lady Sylvia, her saloon windows boarded up for the voyage, was the first single-propellor diesel vessel to cross the Atlantic under her own power. Her trip from Glasgow across the Atlantic, through the Panama Canal and up the west coast appears to have been a rough one. The engineer’s log shows this final entry: “Sunday, 11th July, 5:30 a.m., Vancouver—Thank God!”25

She was renamed upon arrival, as there was already a Lady Sylvia on registry. The Lady Rose first served Howe Sound and the Gulf Islands. During World War II, she was painted battleship-grey and set to work transporting air force and army supplies and personnel between Port Alberni and Ucluelet. She could comfortably accommodate seventy passengers, but at times during the war she transported up to two hundred soldiers and their gear.26 The reliable craft ranged as far up the coast as Prince Rupert, and also transported Pacific Coast Militia Rangers.

After the war, the Lady Rose briefly returned to Howe Sound, before McMinn and Monrufet leased and then purchased her, and she spent many years servicing Ucluelet and Bamfield from her home port of Port Alberni.

Dick McMinn, inspired by his journeys, gained recognition as “the Wheelhouse Poet.”27 During a monumental storm in the Broken Group Islands, McMinn scribbled the lines of his first poem, Storm, which ended with the verse: “Let no man boast / In his tiny voice that his ship is best / When the Southeast god walks in the West.”

He later laughed ruefully as he related that his poem made it to the CBC, where “they read the damn thing over the radio.” Musing on the “tempest of enthusiasm Storm stirred in northwest teacups,” he said: “You can be 40 years master of a ship without a mishap and then you write a poem and everybody knows you.”28 He continued to write poetry, filling fifteen notebooks stored in the cabin below the pilot house of the Lady Rose. Many passengers leafed through the collection over the years.

When McMinn retired, the Lady Rose was soon bought by Brooke George and partners. She carried on her Ucluelet and Bamfield runs, with regular stops in the Broken Group to drop off and pick up kayakers and campers.

Mike Surrell, who later owned the Lady Rose, took her out of service because of the exorbitant cost of upkeep. Tofino’s Jamie Bray, owner of Jamie’s Whaling Station, bought the ship in 2010. When plans to turn her into a floating restaurant were put on hold, she rusted at her Tofino moorage.

In 2019, the Lady Rose was purchased by a group in Sechelt, who planned to restore the iconic ship to her former glory for preservation and display purposes, either on land or for short excursions on the water.

The Frances Barkley

Built in Norway, the Frances Barkley was launched on November 7, 1958, as MS Rennesoy, then renamed MS Hidle, serving in the Norwegian ferry fleet operating out of Stavanger. In 1990, the Alberni Marine Transportation Company bought her, renaming her MV Frances Barkley, after the adventurous wife of early explorer and trader Charles Barkley. The Frances Barkley travelled from Norway to Vancouver Island under the charge of new owner Brooke George and chief engineer Bill Put. After a forty-one-day voyage across the Atlantic, through the Panama Canal and up the west coast, the Frances Barkley arrived in Port Alberni on August 11, 1990, to begin sharing the workload with the Lady Rose.

In August 2021, Mike Surrell, owner of the Lady Rose Marine group, citing the negative impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, announced the business would have to close. The news was met with dismay by Barkley Sound communities like Ucluelet and Bamfield. The Frances Barkley was scheduled to make her last trip on August 31, 2021. There was an all-round sigh of relief when, at the eleventh hour, Greg Willmon and Barrie Rogers, owners of Devon Transport Ltd. of Nanaimo, purchased the business.

The Frances Barkley resumed sailings to Bamfield at least three times a week, adding Sunday to her schedule in August 2022. Although Ucluelet residents have easier access to “out of town” because of the paved highway, regular visits from the Frances Barkley are missed by locals and tourists alike.

Boat Building on the West Coast

Boat building here on the coast goes back thousands of years. The Nuu-chah-nulth built dugout canoes from single cedar trees, chosen following cultural guidelines. Master carvers still build these fine vessels today, with the same graceful bows, flat sterns and flares. The seaworthiness persists, as demonstrated by the annual paddle down the west coast, handling heavy seas and dangerous crossings, such as the Nitinat Bar. Since 1989, First Nations up and down the west coast have participated in this Tribal Canoe Journey, paddling to Washington state to celebrate successful voyages and proud traditions.

Some settlers who came to the west coast travelled in, and fished from, dugout canoes, buying them from local Nuu-chah-nulth people. Others chose different styles of boats, such as rowboats, skiffs, dories or launches. On the isolated coast, ingenuity has long been a necessary trait. The settlers either built their own boats or hired local builders to craft their vessels. Some boatbuilders were self-taught, while others apprenticed to learn the trade.

A busy fishing port like Ucluelet was a prime site for boat building. This need was filled by the Shimizu Brothers Boat Works. Brothers Kiuroku and Toshiro Shimizu came to BC from Japan. By 1922 they had settled at Port Albion on the east side of Ucluelet Harbour. The spot where they built their homes and business soon became known as Shimizu Bay. The Shimizu Brothers Boat Works built wooden fishboats, including the Groom I, the Groom II and the T.S. In 1930, they built the Miss Ucluelet for Kiuroku’s own use.

Japanese Canadian boatbuilders were highly skilled craftsmen who often worked with traditional tools. Their saws and planes differed from the European style, using pull thrust rather than push thrust to achieve a finer, more precise cut.29

The members of the Shimizu family were forced from their homes and interned during the Second World War. The government wrongfully seized most of their belongings, including their boats and woodworking tools. Sadly, that meant the end of the Shimizu Brothers Boat Works, and of this fine family’s time in Ucluelet.

Ucluelet Marine Service

Ucluelet Marine Service was established in 1920 by Mr. Cochrane in a building below the Jack Thompson home on Fraser Lane. Jack Thompson took over the business in 1925, efficiently repairing boat engines in the small machine shop. Hilmar Wingen, well-versed in boat building and maintenance, bought the business from Jack in 1946, building a larger structure next to the original small machine shop. The business changed hands over the years, with owner-operators including Vince Madden, Shorty Craig, Pete Hillier and Ray and Yvonne Vose.

The marine ways section of the business had already been bought from Pete Hillier by Pioneer Boatworks, run by Mr. Jorgenson. The business was eventually sold to Eric Caswell and Bonnie Gurney, who arrived from Minnesota having never run a shipyard or store before. After thirty-five successful years, they sold their business and moved to Duncan to enjoy a well-earned retirement. Keith and Sandy Johnson of Parksville took over Pioneer Boatworks in February 2022.

Boat launches were always a cause for celebration. The Wingen lads, Bob and Harvey, discovered their dad’s stash of boat launch champagne and replaced the true bubbly with ginger ale so they could enjoy the real deal. “We figured that spilling all that good booze at the launch was a great waste,” Bob explained.30

Launching the Thoroughbuilt

George Saggers lost his troller in a gale in 1931, almost losing his life in the process. There was much celebration when, on February 9, 1932, Ucluelet residents gathered for the launch of his new troller, the Thoroughbuilt. The Daily Colonist described the event: “The launching took place early in the afternoon, when Mrs. Mary Baird graciously broke the bottle of champagne over the bow of the vessel, christening her Thoroughbuilt…The trim craft slipped into the water and, at the touch of the engineer, the throb of the engine was heard, the boat immediately getting under way, circling the harbor amid the good wishes and loud cheers of the crowd.”

The Thoroughbuilt then conveyed family members and guests to her anchorage in Spring Cove, and Mrs. Saggers served refreshments…amid toasts “to fair weather, good catches, future prosperity and safe passages.”31

The Colonist described the fifty-foot troller, with its twenty-horsepower Regal engine, as “in every way built and equipped to weather the rough seas and bad storms which the fishing fleet on the West Coast has to contend with.”32 Like all boats constructed by the Shimizus, the Thoroughbuilt was thoroughly built.

From Sea to Sky

Although there had been pre-war commercial flights to the west coast of Vancouver Island, “there were more miles logged in five months after the war than in five years before.”33 Jim Spilsbury and his partner Jim Hepburn had started up a small airline to expedite their mobile radio service. The airline grew into Queen Charlotte Airlines (QCA), which started west coast flights during World War II. Beginning with delivery and service of mobile radios, including regular trips to Port Albion, they soon found there were always eager paying travellers. Sometimes the weather didn’t co-operate. Jim Spilsbury recounted dropping off two Ucluelet-bound passengers at a seine boat in Barkley Sound, as Ucluelet Harbour was fogged in.34

Writer Cecil Maiden heralded this new mode of transportation in a descriptive Times Colonist article in 1951: “Something new is happening on the Other Side of the Island... it could only happen NOW—for it is the opening up by air of a territory that has hitherto been accessible by sea.” The article enthused about the “pioneers of this new age…young, wideawake men with all the dash and venture of those earlier pioneers, plus an up-to-date airmindedness that they have won, for the most part, in battle.”35

Pilot and airline owner Jack Moul, whose flights provided a regular link between Port Alberni and Ucluelet, was one of these early airborne pioneers. Jack started flying at eighteen and joined the air force during World War II. He was shot down while flying a Spitfire over the English Channel, and later said with a grin that he had been “in the wrong place at the wrong time.”36 Jack said he swam for ten hours before being plucked from the water and imprisoned at Stalag Luft III in Germany, the setting of the story chronicled in the movie The Great Escape, starring Steve McQueen.

Jack survived the war and came home to Port Alberni. With fellow ex–prisoner of war Slim Knights, he founded Port Alberni Airways in 1946. It would become amalgamated with Pacific Western Airlines in the early 1950s. Jack and his brother Gordon both served the west coast as PWA seaplane pilots. Jack went on to serve as PWA vice-president from 1983 to 1986.

Jim Spilsbury’s QCA, after a long and intense competition with PWA’s Russ Baker for west coast aviation business, sold to them in 1955.

Gordon Moul purchased his first plane in Port Alberni at the age of fifteen. At sixteen he had his private pilot’s license, and by nineteen he was flying commercially. “I was going to be a doctor…but flying was a lot more fun,” he later said.37

In their early years flying in and out of Ucluelet, the Moul brothers and other pilots communicated by radio with Helen Craig. She operated the PWA office out of a tiny corner room attached to the Craigs’ family apartment above their shop and store. The Craigs owned Ucluelet Marine Service, strategically located at the bottom of Fraser Lane. (The building now houses Jamie’s Whaling Station.) My friend Dennis Craig told me his mother shared local conditions with the pilots by comparing the height of the cloud ceiling with the height of Mount Ozzard across the harbour. The Craig family all enjoyed free flights as a perk of Helen’s occupation.

The float planes used for Ucluelet flights were usually Cessna 180s or De Havilland Beavers. The Beaver was ideal for the west coast, capable of taking off and landing in short distances, handling well in rough water and transporting good-sized loads.

Pilots were expected to keep to the schedule despite foul weather. Jim Spilsbury described the stress of providing air service to the west coast succinctly: “This kind of flying was pushing the margin pretty far.” He added: “It scared me.”38

Like the sea captains before them, the west coast pilots transported passengers up and down the coast, delivered supplies and carried out search-and-rescue missions. More than the weather could prove challenging. Jack Moul recalled transporting a patient with mental illness in a one-passenger plane. The fellow had to be “fed an occasional apple en route (from a bag placed aboard for the purpose) to pacify him until he arrived at his destination.”39

The brave pilots servicing the west coast were sometimes called upon to provide “mercy flights,” transporting patients to cities for medical help.

Although a road would finally connect Ucluelet and Tofino to the outside world, flying continued to be a travel option, both by seaplane and by airplanes using Tofino Airport. Mercy flights are still relied upon, and Tofino General Hospital has an adjacent helicopter pad.

Vaida Siga, a nurse at Tofino Hospital in the 1970s, was given the opportunity to go along on a flight to pick up the federal nurse in Bamfield. When the fog came in, the pilot swooped below it to get his bearings by sighting the wreck of the Vanlene. They never did find Bamfield, but Vaida loved the flying experience, and became a federal nurse, meaning she served reserve communities and federal employment sites. Vaida told me about a flight to Ahousaht when they stopped at a logging camp and it was blowing so hard the plane was going backwards. She added: “When your pilot’s face goes white, you know you’re in trouble.”41

Louis Rouleau arrived on Vancouver Island’s west coast in 1979 to fly the De Havilland Beaver and Cessna 180 float planes for Tofino’s McCully Aviation. Within a week spent in the glorious natural surroundings, he and wife Darlene knew they were in paradise. “But,” Louis told me, “it was the people on the real west coast, the fishermen, the loggers, the First Nations all with their own unique stories who welcomed us to make a home here.”

From his home base of Ucluelet Harbour, Louis provides “flightseeing” tours and charters on his Cessna 180 float plane. Like the pioneer pilots before him, he relishes the challenges of the ever-changing weather and the tricky tides and currents.

The Long and Winding Road

Early settlers on Vancouver Island were promised a road. Pre-emption promos circa 1910 told of a soon-to-be-built wagon road to the west coast. It was a long time coming.

Locals focused more immediate attention on acquiring a road between Ucluelet and Tofino. Early settlers had to hike a rough path out to Willowbrae and into Wreck Bay, then walk the beaches before joining a rough path into Tofino. Sometimes people hiked from Long Beach to Grice Bay and were picked up there by boat. The trek from Ucluelet to Tofino often took two days, with an overnight break spent with Long Beach homesteaders.

It wasn’t until 1923 that a rough road joined Ucluelet to Sand Hill Creek at Long Beach. By 1927 Tofino was connected to the other end of Long Beach, and cars drove along the beaches to link the roads. Drivers had to be careful to venture out at low tide and not get stuck in the sand, as doing so usually meant losing their vehicle to the incoming tide. Vehicles were a precious commodity brought in by ship from “outside.”

In 1936, work continued on the Ucluelet-to-Clayoquot road, with no plan to address the need for a road parallel to the beach. The Ucluelet-to-Long Beach section was deemed by locals to be “in better condition at the present time than at any time previously,” and there was buoying news that it would be “passable all Winter.”42 Owing to winter weather conditions, no more work would be done on the Tofino section until spring.

It took a world war to bring about the completion of the road. The Canadian government wanted land-based aircraft on the coast and put in the Royal Canadian Air Force Station, Tofino, adjacent to Long Beach. The air force pushed through a roadway to join Ucluelet and Tofino to the airport site, and improved the existing sections. The new road, although a vast improvement on the original incomplete route, strewn with branches and sinkholes, was no superhighway. Airman Leslie Hempsall later described it as a “rutted pock-marked gravel surface.”43 However, in 1942 it closed the gap. World War II had finally linked Ucluelet and Tofino by road.

The First Car

The first car in Ucluelet was an 1890 Albion. It was a two-cylinder model with a make-and-break ignition system, and a governor similar to a steam engine, allowing it to go uphill at the same speed it went down. Instead of a horn, it had a steam-engine whistle connected to the exhaust pipe. It was driven by chain sprockets to each rear wheel, and on all four wheels were hard rubber tires. The car was brought to Wreck Bay around 1899 by gold miners. When the vehicle was taken to Cochrane’s Machine Shop in Ucluelet for repairs, he was able to weld the engine but couldn’t time it properly. Jack Thompson acquired the car when he purchased Cochrane’s business. “I used a great many parts from it fixing various gas engines of the time. Having acquired a machine shop with very little material to work with, the old car came in handy. Even the hard rubber tires were used on a horse cart for Mr. C. Hughes but when his horse died shortly afterwards, the career of Ucluelet’s first car was ended!”44

A Road to Port Alberni

With the road now through from Ucluelet to Tofino, pressure continued for a road to the outside world. Pioneer families had been petitioning the provincial governments since 1895. Delegations in the early 1900s pressured the government.

When then premier Richard McBride promised, in 1914, that the matter would be addressed, an article in the Daily News described the ideal route for such a road. It referred to a “low pass, known as Sutton’s,” and went on to say a road could go “across the divide to Kennedy Lake,” adding that “from Kennedy Lake to Ucluelet, and the ocean beach road construction would be very simple.”45 Apparently, they had no crystal ball showing the challenging rock bluff along Kennedy Lake.

The year 1936 saw the start of a trail from Sproat Lake to Wreck Bay, with work crews starting at each end. This trail was viewed as a first step towards building the road. An overly optimistic assessment stated: “The survey of this route shows easy grades, few bridges and is estimated to be a relatively easy road to build.”46

During World War II, the air force put in a telegraph line from Port Alberni to Tofino Airport. This line basically followed the route later taken by the highway, and remnants of the line can still be seen along Highway 4. Telephone lineman Ron Matterson often walked the trail on routine line patrol. Prospectors had used the same route since the 1890s to bring supplies into mining claims.

In the spring of 1949, the Ucluelet Scout Troop hiked the trail from Ucluelet to Port Alberni. After the adventurous three-day hike, they returned home to Ucluelet aboard the fishing vessel Hillier Queen.

Also in 1949, the Ucluelet and Tofino chambers of commerce joined forces to advocate for the cause. Committee members took the same route the Scouts had taken through the mountainous terrain of forest, bush and bog, stating their case at Port Alberni at the end of their hike.

Finally, in 1955, there was some action. Two forestry companies took on the task. BC Forest Products agreed to build the most challenging, western section. This included major blasting and drilling at the Kennedy rock bluff. MacMillan and Bloedel put in the Sproat Lake section, joining up existing logging roads and building new ones. This included the switchbacks, a narrow section with hairpin turns, at its highest 580 metres, with no barricades separating the road from the drop-off to the lake far below. The BC Department of Highways built the twenty-kilometre middle segment known as the Government Stretch.

The soon-to-be-open road was described as “in many parts a tire-ripping, chassis-shaking terror to anyone but operators of logging trucks, for which most of it was originally gouged out of the hills.”47

When the entire rough route was connected, Stu Crawford drove the road in a MacMillan and Bloedel company truck, with Jim Christian as passenger. Stu, then the engineer at M&B’s Sproat Lake Division, along with Jim, had been tasked with regularly checking on the road’s progress. On July 20, 1959, they drove right through to Ucluelet, passing another driver who had tried to be the first through and “got his car stuck fast in a gully.”48 Jack Moraes of Long Beach marked the occasion with the presentation of a glass ball inscribed “Alberni to Long Beach. First vehicle through July 20, 1959. Jim Christian and Stu Crawford.”49

Finally, in August 1959, the road opened for locals. I missed out on the “grand opening.” My father didn’t like crowds, so we drove out the day before. Dad had a key to the gates and wanted to beat the rush. I can clearly remember him telling my mother: “I don’t plan to stick around and eat dust all the way out tomorrow!” We piled into our 1958 green Ford station wagon—Mom and Dad, my brothers Robbie and Ian, family friend Terry Smith, and me—and by the next day’s grand exodus, we were already en route to a camping holiday in Alberta.

On August 22, many Ucluelet and Tofino residents headed out in a convoy. Seventy-four vehicles, carrying three hundred people, left the junction at 6 a.m. There were four rules set for the convoy members: 1) No passing. (My father would not have liked that one!) 2) Stay close to the vehicle ahead. 3) Stop only at the four designated stops. 4) Don’t throw matches or cigarettes out the window and don’t smoke at the stops.

It was a long and bumpy drive. George Gudbranson stood by with his tow truck to pull any struggling vehicles through one particularly massive mudhole. The group stuck together and made it to Port Alberni. Some celebrated there, while others carried on to Nanaimo for an official welcome and a group photo at Beban Park.

Ann Branscombe rode with her sister and brother-in-law, Nancy and Lowell Panton. She said pretty much every car owner in town filled their vehicle with passengers and headed out, eating dust and bouncing through potholes. When they finally arrived in Port Alberni, Lowell’s mother had a picnic for them on her lawn.

The road was formally opened on September 4, 1959, and swarms of people arrived on the coast. In a previously unheard-of phenomenon, one west coast gas station ran out of gas by 4 p.m. Visitors tore up and down Long Beach in their cars. Civilization was no longer knocking at our door; it had now breached the divide. It brings to mind the phrase “Be careful what you wish for.” Once the road went through, development continued to gallop forward, with no end in sight.

Phil Gaglardi, highways minister at the time, warned that in the event of snow, the new highway would likely be closed, describing snowplowing as “dead money” and saying the road would not be plowed unless enough traffic warranted it. He emphasized that boat connections were being maintained “under provincial government subsidy as an alternative to road travel.”50

The road initially remained an active logging road. Gates at both ends were locked to non-logging vehicles during the day, making night driving a necessity. In 1964, the gates were removed, and people were free to drive in daylight hours. But driving the road was not for the faint of heart. It was pretty much a given you would lose a muffler or pierce an oil pan. It gave new meaning to the phrase “Shake, rattle and roll.” A local bus driver was so frustrated that one night he “borrowed” a Highways grader to smooth out an eight-kilometre bumpy patch. Local GP Dr. McDiarmid recalled traumatized tourists requesting Valium before heading back out of town.

Jim Forbes, chairman of the Ucluelet Village Commission when the road opened, estimated the government cost of putting the road through at $500,000, and figured the two logging companies involved had each paid that much as well. He also commented that anyone thinking they could take advantage of all the tourists and set up some beach-side accommodation would need to have money, as beach frontage was selling as high as thirty dollars a foot.

On October 14, 1972, an official ribbon-cutting ceremony marked completion of the paving of Highway 4. That same year, the Department of Highways did away with the switchbacks, so we lost the thrilling view of the lake far below, and the palpitations induced by each hairpin turn. The road alongside Sproat Lake is smoother and faster, but a tad less scenic than the old switchbacks.

Although the paving of Highway 4 was completed in 1972, the need for maintenance and improvements is ongoing. And while it is true that “away” is more achievable with the road, we are still at risk of isolation from the outside world. Over the years, the road has been closed because of snow, or washouts from our considerable rainfall. Another example of our reliance on the one route out is the Tay Fire of 1967.

The Tay Fire

On August 16, 1967, road crews working near Taylor River Bridge set off a blast, and a dislodged rock knocked over a hydro pole. The live wires hit tinder-dry ground, causing instant ignition. The fire spread swiftly owing to extremely dry conditions and high winds. Ucluelet, Tofino and adjacent communities were left without electricity. The road was closed, cutting off access to the outside world. The billowing plume of smoke could be seen from Ucluelet.

The firefighting logistics came under the jurisdiction of the BC Forest Service. Because of extreme heat that summer, most MacMillan Bloedel divisions employees were laid off, owing to voluntary wood closures. Here on the coast, it was cooler. Terry Smith recalls arriving at the marshalling yard at Kennedy Lake Division in drizzle and heavy fog. They were told: “There’s no work here today…you’ll be fighting fire.” Lemie La Couvee was in charge as Kennedy Lake Division’s fire warden.

Every able-bodied male was urged to fight fire. I remember my brothers, then aged nineteen and twenty, coming home after firefighting shifts of twelve hours or longer, hungry, thirsty, bone-tired and reeking of smoke.

Taylor River Bridge was destroyed by flames and replaced four days later by a Bailey bridge. Hydro power was eventually restored to the west coast. The fire burned out of control for sixteen days. By the time it was subdued, three thousand hectares had burned. The Martin Mars water bombers stationed at nearby Sproat Lake were in great demand, but at times had engine issues due to the extremely high air temperatures. One crew member recalled flying over the fire when flames from a treetop shot up past the plane in one of the updrafts.51

All available workers and resources fought the fire, but relief did not truly arrive until rain finally began on September 1 and continued for five days straight. The fire was officially declared out on October 10.52 Many trees were still standing, their branches and bark stripped by the intense heat. Those trees were logged for some years after. It was a dirty job. Macmillan Bloedel set up on-site showers, but by the end of each day exhausted loggers didn’t want to wait in line, so they headed out, black and sooty, to shower at home.

It took twenty years for the area to green up again, and you can still see evidence of the Tay River fire.

Kennedy Hill Upgrade

Highway 4 has been the site of many accidents over the years. On October 19, 2010, two well-loved west coasters, the veteran paramedics Jo-Ann Fuller and Ivan Polivka, lost their lives when their ambulance went into the lake off a narrow, windy section of Highway 4. This tragedy instigated improvements to the dangerous stretch of road called Kennedy Hill.

The provincial government initially consulted with Ucluelet and Tofino residents in public information sessions about proposed improvements at the beginning of 2018. Ultimately, a one-and-a-half-kilometre section of the highway, running along Kennedy Hill next to Kennedy Lake, was widened, regraded and paved. The project took much longer than anticipated. Massive blasting caused many road closures, both planned and unplanned. Occasional major rock slides closed the road for days at a time. When the dust finally cleared and the project was declared complete in the spring of 2023, the final cost was $53.96 million. The delays were attributed to the Covid-19 pandemic, blasting damage to the site, increased environmental protection requirements and the nature of the fractured bedrock.53

The long-drawn-out project fuelled discussion about the need for an alternative west coast route. More proponents of this idea came forward when, in June 2023, Highway 4 was closed at Cameron Lake Bluff because of a forest fire. Dialogue about an alternative route to Port Alberni and the west coast continues.

The highway linking Ucluelet and Tofino to the outside world is no longer the dusty, washboard, gravel logging road of the past. But as of the writing of this book, driving it is still a challenge. We get snow. We get washouts. Sections of the road sink. Potholes abound. Slow drivers don’t always use the pullouts to let others by. People get impatient and pass in dangerous places. With the number of west coast residents and visitors steadily on the rise, road maintenance and improvements continue to be a hot topic here.