Chapter 9: Barkley Sound

When the Good Ship Princess Maquinna reaches Chup Point, 2 nautical miles (3.6 km) past the entrance to Uchucklesit Inlet on the north side of the Alberni Canal, she rounds the point and steams northward through the islands of the Broken Group. Her next destination is the small dock at the BC Packers reduction plant at Ecoole. The facility here began as a saltery in 1916 that, a decade later, would become a more profitable pilchard reduction plant. After a brief stop of less than half an hour, the Maquinna steers across Imperial Eagle Channel. The passengers now have a brief break from the reek of pilchard reduction plants, but earlier in the Maquinna’s career something even worse had awaited at the next stop. The whaling station at Sechart was, until its closure in 1918, one of three whaling facilities the Maquinna visited along her route, the others being Cachalot in Kyuquot Sound and at Coal Harbour in Quatsino Sound. Long before the Maquinna reached Sechart the stench drifted toward the passengers on board. “The odor was indescribable—we literally gagged,”95 reported one passenger. The plants employed scores of workers, many of them Chinese and Japanese, who flensed the whales and rendered the blubber into whale oil and fertilizer, canning the meat or “sea beef” for pet food. Transporting these items to Victoria for trans-shipment overseas gave a massive boost to the CPR’s bottom line.

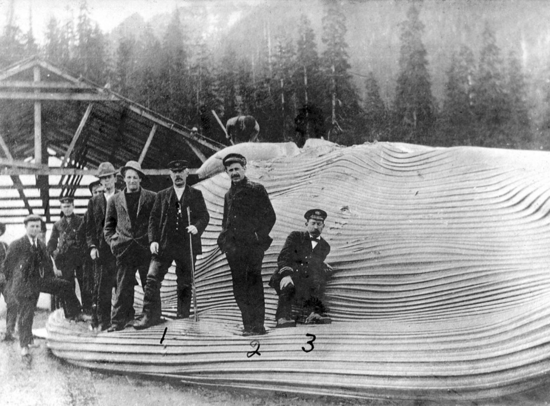

Opened in 1905 by the Pacific Whaling Company, the Sechart plant and the one at Cachalot between them slaughtered 5,700 whales, the majority of them humpbacks, between 1907 and 1925. “Passengers and crew would disembark for a quick tour, keen to view the great piles of bones and baleen and eager to be photographed alongside the immense carcasses awaiting flensing,” wrote Mr. H.W. Brodie, the CPR inspector touring the coast in 1918. He could not quite comprehend this, appalled as he was by “the indescribable stench [that] prevails at the whaling station... and make a large number of people very ill.”96

After an hour’s stop the Maquinna continues on to the pilchard plant at Toquart for a typical and uneventful stop before rounding the point at the northern entrance to Barkley Sound, just beyond which she reached the village of Ucluelet, meaning “people with a safe landing place.” Protected on the southwest by a narrow peninsula of high ground a couple of miles long, Ucluelet possesses an excellent harbour, about half a mile (800 m) wide and deep enough for coastal freighters.

The Ucluelet First Nations village sits along the east shore of the harbour, as does the Nootka Packing Company’s Port Albion reduction plant, and some scattered settlement. On the west side of the bay sits the government wharf and the busy village of Ucluelet, much of the shoreline taken up by docks for fishboats. “The outer ends of the floats were occupied by fish buying stations and a couple of oil barges,” writes Al Bloom in his diary. “This was the permanent home of many trollers, the majority of them Japanese. They were an industrious group of people, who kept their boats and their home sites in first class condition. They worked hard and made a good living, even though the best price for fish was thirty or forty cents a pound.”97

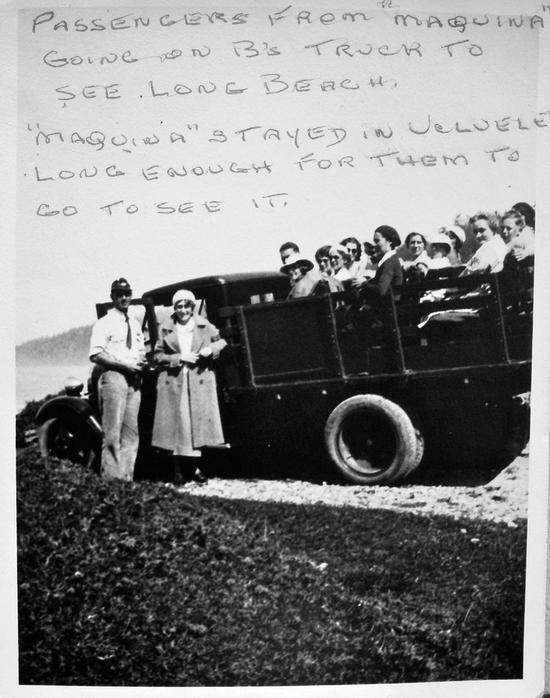

While the Maquinna pauses at Ucluelet, the tourists aboard prepare to enjoy a local horticultural delight. Here they can go ashore and visit the “Kew Gardens of the West Coast,” a widely renowned four-acre garden established by pioneer horticulturalist George Fraser. Others may choose a different local attraction, and can take a truck ride out to the beaches north of the village, including the magnificent Long Beach, the west coast’s most famous strand.

Born in 1854 near Fochabers in Scotland, from the age of 17 George Fraser apprenticed as a gardener at nearby Gordon Castle. After completing a four-year course in horticulture in Edinburgh, and having worked on other large estates in Britain, he immigrated to Canada in 1883. He arrived with his sister in Winnipeg, hoping to own land of his own. After two years, he found the harsh winters not to his liking and moved to Victoria, where he established a successful fruit and vegetable garden. When the city of Victoria commissioned a fellow Scot, John Blair, to design and build Beacon Hill Park, Blair hired Fraser as his foreman. While doing this work, Fraser found time to travel to Ucluelet, and in 1892 he purchased Lot 21, consisting of 236 acres, for $236. Today, Fraser’s original landholding accounts for almost half the land in the village of Ucluelet.

In 1894 Fraser left Victoria and settled on his land, where he set to work creating a magnificent garden that would attract worldwide attention (though sadly it does not survive today). Later, his brothers James and William joined him.

Setting about building his garden, Fraser encountered rocky ground and poor soil, but he persevered, undaunted even by the 120 in (3 m) of rain a year. He constructed underground wooden drains to draw the water away, he built his soil by collecting seaweed, fish refuse and cow manure, laboriously transporting these from farther up the inlet on a scow, which he towed behind his rowboat. Over time he began growing fifteen types of heather, adding many varieties of rhododendrons, azaleas, roses, fruit trees, berries, and shrubs of all kinds. He started his plants in rooting beds heated from below with warm smoke that made its way inside a clay-tiled flume from a small wood burning heater in his house. Fraser was a happy and friendly man, and his skills as a fiddler came in handy at community events. He became a beloved and well-known figure in the area, though Fraser’s reputation spread far beyond the west coast. He already had a respected record as a grower and landscaper when he came to Ucluelet, and from this unlikely location his fame spread. As his garden matured, and the species he grew multiplied, he created mail-order catalogues. He sent orders far and wide, his plants carefully packed in sphagnum moss, and shipped inside wooden crates he made from driftwood. They all left Ucluelet aboard the Maquinna. He even sold plants and shrubs to the CPR to enhance many of the company’s gardens. His reputation as a planter is best remembered for his skill in propagating hybrid rhododendrons and azaleas. He corresponded with fellow enthusiasts around the world, shipping plants and pollen to growers in England and the United States. One of his hybrids, Rhododendron ‘Fraseri,’ still grows in world-renowned Kew Gardens in London.

Fraser warmly welcomed visitors who walked up to his garden from the Maquinna. In the spring and summer the ship extended her stay so that passengers could enjoy the gardens in full bloom. Fraser would take them on tours, and when they departed, regardless of whether they bought plants or not, he gave them a bouquet of flowers before they returned to the ship. In 1944 Fraser died, aged 90, and when he was being taken aboard the boat to go to the Port Alberni hospital, from which he would not return, he is reported to have said: “I don’t know where I’m going to end up, but it doesn’t matter—I’ve had my heaven here on earth.”98

In the 1930s, when the Maquinna stopped in Ucluelet tourists could board Basil and Mary Matterson’s “tour bus”—an open truck with seats built onto the flat bed—and take a 12-mile (20-km) ride over the rough, gravel road connecting Ucluelet with Long Beach, one of Canada’s greatest natural attractions. In those days, Long Beach formed part of the route travelled between Tofino and Ucluelet, with cars and trucks motoring along the hard-packed sand. Travellers considered this section the best and smoothest part of the whole journey as the road on either side of Long Beach often proved impassible.

Between 1942 and 1944, during World War II, nearly a thousand air force personnel served at the amphibious air base established in Ucluelet. Stranraer and Shark float planes from the base patrolled the west coast looking for enemy submarines, and for any signs of a Japanese invasion fleet. It proved a lonely existence for the young men stationed there, and when they received forty-eight-hour leaves, every three or six months, they would make the long, multi-stage trip to Vancouver. First they had to travel to Port Alberni on the Maquinna, Lady Rose or Uchuck, then take the train to Nanaimo, where they boarded the CP ferry to Vancouver, arriving late in the afternoon. The return trip by ferry and train landed them back in Port Alberni just after midnight the following day, where some might take a room in the Somass Hotel while waiting for the Lady Rose or Uchuck to depart in the early morning. Five hours later they reached Ucluelet, where they could reminisce for the next several months about their short but exhilarating time spent partying in Vancouver.

With her passengers back on board, the Maquinna unties and rounds Amphitrite Point—named for Poseidon’s wife in Greek mythology. The lighthouse on the point, built in 1906, resulted because of the tragic sinking of the three-masted steel-hulled barque Pass of Metford. On Christmas Day 1905 the vessel foundered on the treacherous rocks lying just offshore, with a loss of thirty-five lives.

After enjoying the calmer waters of Alberni Inlet, Barkley Sound and Ucluelet’s protected harbour, the passengers must now brace themselves. Once again, they are heading into the powerful swells of the open Pacific. The waves come at them unimpeded, across some 6,000 miles (nearly 10,000 km) of open ocean, all the way from Asia. Even if the weather appears sunny and windless, the swells driven by storms farther out in the Pacific still pack a wallop. Johnnie Vanden Wouwer recalled one trip from Bamfield to Tofino: “By gosh there was a big storm! When we got round Amphitrite, Dad was just about all in. Oh, seasick! It seemed to be taking forever and ever to get to Lennard Island in that big swell and she had a full load, too. I was throwin’ up and I could hear the propeller come half out of the water and what a crash it would make when it came down! And that Jenny Reef seemed awful close.”99

Ray Jones, who lived in Port Alice and who travelled on the Maquinna from the time he was 7 years old, could relate to this. During one particular storm when he was very young, “the water churned over the tip-tilting decks and nothing but green water could be seen through the portholes. Everyone was directed to stay in their staterooms. For me as a child, it was remarkable to see a steward with arms and legs wrapped around a pole, trying to stay upright, and even more remarkable to see my mother holding a teapot up at the dining room table in the saloon as the crockery crashed to the floor. ‘Oh son, we’re going to drown,’ she cried. But we didn’t. The Maquinna was more than equal to such storms.”100

And so she sturdily plows ahead through the swells, with passengers now looking forward to their next major stop, Tofino. First, though, they will pass near to the location where the Maquinna met her greatest challenge, in a storm some years earlier, when not even Captain Gillam could succeed in his brave efforts to rescue a foundering ship.