Chapter 2: BC Built

When Captain James Troup moved to Victoria in 1901 to become the CPR’s West Coast shipping superintendent, he launched a shipbuilding program concentrating on the most profitable CPR routes between the most populous centres: Vancouver to Victoria and Nanaimo, Victoria to Seattle, the Gulf Islands route, the Northern BC and Queen Charlotte run, and the Alaska run. Finally, in 1908, Troup turned his attention to the less lucrative and less populous route along the west coast of Vancouver Island. Although by this point he had participated in designing nine Princess ships since becoming superintendent—the Victoria, Beatrice, Joan, Royal, Charlotte, Adelaide, Mary, Alice and Sophia—Troup knew, even with all his experience, that he faced considerable challenges when he received the go-ahead to build a new Princess ship for the west coast run. Seeking help in understanding the conditions his new ship would face, Captain Troup consulted the Tees captain, Edward Gillam.

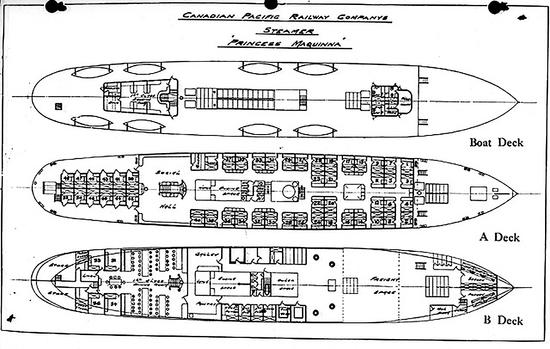

Together Gillam and Troup agreed that the new ship should be double-hulled as a safety measure, given the rocky coast she would travel. They also agreed that the upper deck structure should be kept as low as possible to reduce rolling in the Pacific swells; that all decks, save the top boat deck, should be enclosed by the ship’s steel sides; that large observation windows on the promenade deck, characteristic of other Princess boats, be eliminated; that the hatches be situated forward, and the cabins, smoking lounge, public rooms and dining room be aft of the hatches (the most comfortable place on a pitching vessel in a storm); and that the aft end be made as sleek as possible to keep the stern from rising in heavy seas, thus preventing the propeller from racing if it lifted clear of the water as the ship plunged into a swell. They also suggested the ship’s sides be as perpendicular as possible to enable her to more easily load and unload at west coast wharves in heavy seas and high winds. They planned that the ship would handle four hundred day-passengers, but only provided about fifty staterooms with upper and lower bunks, meaning many passengers would often have to spend nights trying to sleep in the lounge.

By October 1911 shipyards in Britain—and Bullen’s shipyard in Esquimalt (the BC Marine Railway Company)—were busy scrutinizing the CPR’s seventy-five-page specification document for this new west coast ship, each working hard to earn the contract. For the first time in such a competition, the bids from British shipbuilders came in higher than the local shipyard. J. Mason, assistant to the vice president of the CPR in Winnipeg, wrote to Troup on October 18, 1911: “The President [Sir Thomas Shaughnessy] has tenders now in hand for the west coast steamer, the lowest of which is £44,000 in the Old Country, which is approximately $220,000.00. The cost of getting her out here is about $25,000.00, and then about $5,000.00 for cleaning her up, which would make her cost about $250,000.00 here. Bullen’s have agreed to build the same steamer for $250,000.00 here and deliver her to us for that money. We could get a little more for our money in the Old Country in the way of furnishings, but in view of the low figure, I have recommended to the President that we give them the contract.”11 Bullen’s readily signed the contract.

Because the steel needed to build the new ship had to be ordered and shipped from Britain, workers at Bullen’s yard in Esquimalt could not lay the keel of the new ship until May 1912, after the freighter Bellerophon arrived from Britain with the first “... shipment of plates, angles, frames and other components.”12 For the next six months Bullen’s workers concentrated on building the hull so that by November, when the freighter Talthybius arrived in Victoria with the engines, boilers and shafting, they could be quickly inserted into the completed framework. When completed, she was 1,777 tons, 244 ft (71 m) long, 38 ft (13.5 m) wide and with a draft (depth underwater) of 17 ft (7.3 m), making her the largest such ship ever built in British Columbia to that time.

On Christmas Eve 1912, Mrs. Fitzherbert Bullen, wife of the shipyard’s owner and the granddaughter of BC’s first governor, Sir James Douglas, smashed a bottle of champagne across the bow of the new ship, christening her the SSPrincess Maquinna, and the ship slipped down the ways into Esquimalt Harbour. “Only those immediately connected with both companies [CPR and BC Marine Railway] saw the fine vessel take to the water, which she did smoothly and gracefully... as soon as the vessel began to move down the ways, Mrs. Fitzherbert Bullen broke the traditional bottle over her prow and christened her after the native princess whose father was Indian Chief at Nootka when that place was visited by early British and Spanish explorers in the 18th Century,”13 reported the Daily Colonist of the launch.

Here again the Maquinna stood out from the other Princess ships in Troup’s fleet, all of which to that date had been named for European princesses. In a letter dated August 14, 1912, Captain Troup wrote to George Bury, vice president and general manager of the CPR in Winnipeg, taking a different direction entirely: “I believe, when you were out here I told you I had a suggestion for a name, and that is ‘Princess Maquinna.’ I believe, in the past, names have always been submitted to the President for approval. At any rate, I will be glad if you will say if this name is approved. If not, let us have one. My reason for proposing such a name is that once upon a time there was a ‘Princess Maquinna’ at Nootka Sound, on the west coast of Vancouver Island, the daughter of the old Chief Maquinna, who dominated the Indians at the time Captain Vancouver was there.”14

On August 28, 1912, Troup received notification that President Shaughnessy had approved the name. On September 6, in a Daily Colonist letter to the editor, Captain Frederick Longstaff, who became a noted BC nautical historian, wrote that the credit for suggesting the name actually belonged to Captain John T. Walbran, who commanded CGSQuadra from 1891 to 1908, and who in 1909 had published the classic volume British Columbia Coast Names: Their origin and history.15

Once the SSPrincess Maquinna settled in the water, the detailed work of fitting out and finishing began. The wooden decks had to be laid and caulked, the cabins built and furnished, the kitchens installed, the dining room completed, the instruments on the bridge put in place, and a host of other tasks finalized before the ship could take her first sea trial and be accepted by the CPR from Bullen’s yard. That meticulous work took the better part of five months, and as the ship neared completion a Colonist article dated May 6, 1913, could hardly contain itself in praise of the new ship:

"Such splendid progress has been made in the construction of the new Canadian Pacific steamer Princess Maquinna during the past few months that the vessel is now rapidly nearing completion at the Esquimalt shipyards of the British Columbia Marine Railway Company, and preliminary arrangements are now underway for her steam trials. The Princess Maquinna is undoubtedly the largest and finest vessel that has ever been turned out of a British Columbia shipbuilding plant, and its construction compares favourably with any vessel of her size on the Pacific Coast... The Maquinna was designed and built specially for the West Coast of Vancouver Island trade and should prove herself a splendid sea boat in plying the storm-battered coastline. The outstanding feature of the new craft is that all her decks, with the exception of the boat deck, are enclosed by the steel sides of the vessel, and the total absence of housework above the awning deck is a feature that cannot be duplicated by any other vessel plying the Pacific. This handsomely designed coastal craft is considerably longer than the steamer Princess Royal, which was the last large steamer to be launched from the BC Marine yards. The Princess Maquinna, when finished, will be a marvel of skilled workmanship that could not be excelled in any other shipyard in any part of the world. The building here of such a craft means much to Victoria as a centre of shipbuilding activity, and augurs well for the construction in the immediate future of steamships of much greater dimensions than the one that is about complete at Esquimalt.16

"

The article went on to outline the ship’s technical specifications in great detail, before describing the “eight metal, seamless lifeboats, of a size to suit Canadian requirements, 22 feet long,” the “complete system of electric lights throughout the vessel,” not to mention the firefighting equipment on board, right down to the length of the hoses. As for the speed of this vessel, the Colonist breathlessly announced how “the contract calls for a speed of 13½ knots, but it is expected that she will eclipse this during her trials.”

The local pride and interest generated by the launch of the Maquinna even manifested itself in the name given to a baby girl. Mrs. A.J. Daniels, wife of the shipwright foreman for Bullen’s, gave birth to a daughter shortly after the ship’s launch. The couple named her Maquinna. Later in life, Maquinna Anderson became an exceptional pianist, well-known throughout British Columbia.17

All up and down the west coast of Vancouver Island, local people who had long waited for their new steamer followed every detail of the shipbuilding progress with keen interest. This would be their ship, and she was being built especially to serve them. They began making preparations to welcome their new vessel.

As the date of the Maquinna’s maiden voyage neared, Captain Troup wrote a letter to Bullen’s on July 14, 1913, advising the shipyard that “we expect to bring the ‘Princess Maquinna’ from Esquimalt to our wharf here [Victoria] tomorrow, Tuesday, and to have her sail on the regular west coast sailing Sunday, July 20th... I propose to go myself as far as Holberg, and would be pleased to have the General Passenger Agent, the General Freight Agent, District Freight Agent or Assistant General Passenger Agent, make the trip also.”18

In a letter to J. Manson, vice president to CPR president Shaughnessy, Troup wrote on July 15: “After preliminary steam trials ‘Princess Maquinna’ was taken over by us to-day.”19 The next day the CPR paid the BC Marine Railway Co. the final $30,800 instalment of the $245,000 contract price for building the Princess Maquinna.

Four days later, on Sunday, July 20, 1913, Captain Gillam ordered steam from the Maquinna’s oil-fired boilers to be injected into the three-cylinder, triple expansion engine. At 11 p.m., as she would do for the next thirty-nine years, the new west coast steamer SSPrincess Maquinna eased out of the CPR’s Belleville Street terminal in Victoria on her maiden voyage up the west coast of Vancouver Island. On board were George Bury, Captain Troup and other dignitaries, as well as members of the general public lucky enough to secure passage at “$24 for the five-day sail, which is less than board and lodging at a decent hotel,”20 filling up “the greater part of the steamer’s accommodation.”21

A CPR report on the maiden voyage states that when the Maquinna eventually reached Bamfield, at the entrance of Alberni Inlet, at 11:05 a.m. the following morning, the entire community was on hand to view the new ship. When docked “a gasoline boat arrived with all flags flying, and a band of music on board. The band was transferred to the ‘Princess Maquinna’ and at 1:16 p.m. the voyage continued.”22 When the vessel reached Port Alberni at 3:45 p.m., after the 30-mile (50-km) journey down Alberni Inlet, the band began playing on the top deck as a host of launches, small tugs and floating craft of all description, with bunting and whistles blowing, greeted the Maquinna. The industrial whistles of the Canadian Pacific Lumber Co. mill and the Wiest Logging Company added to the din. After tying up, the mayor of the city, along with a number of residents of Port Alberni and Old Alberni, assembled in the ship’s dining lounge and addressed Captain Gillam, extending their congratulations.

Even when the ship arrived at Ucluelet at 4:00 a.m. on July 22, though “the hour was too early for the citizens to be out... banners welcoming the steamer were stretched across the roadway and wharf, and every evidence of welcome to the new boat was displayed.”23 “At Clayoquot, Kyuquot and many of the Indian Villages, the Indians turned out in large numbers to see the new boat, and were very much interested.”24 “At Kakawis, when the ship stopped at the Christie Residential School every Indian boy and girl who could get into a canoe came out alongside. A welcoming salute was fired from an old Spanish cannon, which is one of the old time relics preserved at this place. The trip continued without any special incident, on to Nootka, Kyuquot, Quatsino and Holberg, and great pleasure manifested all along the line on account of the arrival of the commodious ‘Princess Maquinna’ to replace the smaller steamers previously on the route.”25

Despite the general satisfaction, even when the ship experienced a heavy westerly blow between Kyuquot and Quatsino, which the Princess Maquinna handled very well in quite a heavy sea, Captain Troup noted in his report on the journey:

"One serious matter with the improvement of this service, which was brought home to me on this trip, was the inadequacy of the wharves. Many of the wharves on the West Coast are literally more than half long enough to accommodate a steamer as the Princess Maquinna and many of them are worm eaten and practically ready to fall down; hence I am afraid it will be very difficult to keep a boat of her size from doing damage to the wharves, unless they are improved. I have done what I could to draw this to the attention of the Authorities, and hope to have some of them, at least, improved in a short time... The effective way to bring it about will be to continue the steamer through the summer months and withdraw if the wharves are not improved. This is my present plan, which will no doubt stir up the populace and have the desired effect.26

"

As well as complaining about the west coast wharves, Troup wrote to the BC Marine Railway Co. on July 28, 1913, outlining some defects with the Maquinna that were “putting us to considerable expense, in fact, serious expense, and for which we must hold you responsible.”27 The baffle plate in the condenser had come loose; the reverse gear cylinder proved defective; the winch drum on the starboard side was bent; the steering gear did not work well and did not allow the ship to come over hard to starboard; the boiler stays were inserted too rigidly, causing the rivets to leak; and the soil pipes in the water closet on the main deck were found to be blocked.

In August 1913, despite the rousing welcome and the high hopes of west coast residents for their future transport, Captain Troup removed the Maquinna from the west coast route to make a special run to Alaska, replacing her with the Tees. The Maquinna took seventy delegates north to Skagway to attend the International Geological Congress, and while on that voyage she suffered the first of many mishaps she would experience in her lifetime, when she struck an uncharted rock in Yakutat Bay, Alaska. On her return to Victoria, Troup ordered the Maquinna hauled up the ways of the BC Marine yards at Esquimalt to replace twenty dented plates and attend to the list of other repairs, at a cost of $12,000. She returned to her west coast Vancouver Island route for the fall of 1913, but in January 1914 Troup again placed her back on the Alaska run, where she gained much favour for her seaworthiness and fine accommodations. People living on the west coast were most chagrined at having had the SSTees, once again, foisted on them.

Few ever described the Tees as elegant: “she was sturdy, reliable, and by all accounts impressively ugly,”28 writes Margaret Horsfield in Voices from the Sound. Captain Adam Smith, who sailed her from Britain to Victoria, stated that a better sea boat was never built, and that “She rides the water like a duck.”29

Not all agreed. “It was popularly conceded that the wallowing old tub never sheared the water, she pushed it ahead of her,” wrote Tofino’s Mike Hamilton in his memoirs. “Boy, that blinking old tub could roll and take a nose dive at the same time, so much so that hardened sailors got seasick on her...” and, as for her cabins, they were “more like the accommodation that would be provided for the Slobovians of L’il Abner fame... with a ‘chamber’ pot provided, and a ewer and basin; a narrow hard bunk and I can’t remember if we had electric light.”30 (She did.) But lighting did nothing to improve Nan Beere’s memories of the ship. Youngest daughter of Harlan Brewster, the Clayoquot Cannery owner and future premier of the province, Nan recalled that the Tees became known as the “Holy Roller,” legendary for the seasickness she caused as she pitched and rolled her way up the coast. “I was sick thirteen times on one voyage on the Tees,” she recalls. “Into a white hat, I remember.”31 On February 26, 1914, the Daily Colonist reported:

"In replying to criticisms levelled against the company in connection with the withdrawal of Princess Maquinna from West Coast Vancouver Island (WCVI) route, Capt Troup remarked that the Maquinna was an expensive boat to operate on the WCVI during the winter months, when the freight business was at its lowest ebb. He stated that when the company built the Maquinna it was looking to the future with the object of building up a big tourist trade between Victoria and WCVI, and he emphasized the point that during the winter months when the tourist travel was nil, such a boat as the Maquinna was operating at a loss. “As a matter of fact,” said Capt Troup, “The Maquinna last December failed to do anything like the business Tees brought in during the same period of the previous year.” The result was that the losses to the company were exceptionally heavy in operating the Maquinna during November and December. During the spring and summer months the CPR expected to build up a big trade with the WCVI, when the Maquinna, with her superior passenger accommodation, will be a paying proposition.32

"

True to his word, in early April 1914 Troup put the Maquinna back on the west coast run, where her return “will be hailed with joy by the inhabitants of that route, who resented the temporary withdrawal of the steamer from the service.”33

Soon after Troup reinstated the Maquinna, Captain Longstaff took the opportunity to travel on her up the west coast. He praised the seaworthy qualities of the ship and presciently suggested that the Princess Maquinna “will speedily become one of the most popular excursions for visitors to the Island. The beautiful scenery, the constant variety of the Coast and its primitive Indian settlements whence the natives come out in their canoes to handle their own freight, all combine to make it an experience altogether out of the common and especially fascinating to those who are paying a visit to the Island for the first time.”34 She would sail from Victoria on the 1st, 10th and 20th of each month to Holberg in Quatsino Sound, but on the trip of the 10th she would omit some intermediate stops, making for a faster journey than on the 1st and 20th trips. So popular would she become that, despite temporary departures, the Maquinna would run up and down the west coast almost without interruption for the next thirty-nine years.