Chapter 19: The Final Years

With the war years behind her the Maquinna continued her faithful service up and down the west coast of Vancouver Island. By 1945 she had been on this route for thirty-two years, and like her sister Princess vessels, she was reaching the end of her serviceable life. Six of the Princess ships built by Superintendent James Troup in the 1910s and 1920s had been on the water for more than thirty years and, despite regular upkeep, they were becoming decidedly dated. To compound matters further, as the vessels aged, passenger and cargo traffic had slowly declined, due to new roads and new airline services. It became clear that the CPR management faced some serious decisions about its post-war business model. The people of the coast knew the old ship had problems, and many realized the Maquinna’s days were numbered, but no one wanted to see her go.

In her many years on the west coast, the Maquinna lost a few passengers, several to suicide and some because of medical problems while on board. However, the worst tragedy the vessel ever experienced, in terms of loss of life, occurred near the end of the Good Ship’s years on the coast. In January 1949, while the Maquinna steamed at night from Nootka to Tahsis, she collided with a smaller vessel. While steering NW-by-W near Bodega Island, the Maquinna’s bridge crew sighted a white light off the starboard bow. The helmsman altered course to starboard (the narrow channel did not allow a turn to port) but suddenly the light closed rapidly, forcing him to turn even harder to starboard three more times. At 2:43 a.m., fearing a collision, Captain Peter Leslie ordered the engines full astern. Nonetheless, the Maquinna struck the MVLorraine a moment later on the starboard quarter. Leslie ordered the engines stopped while his crew threw lifebuoys to people from the badly damaged Lorraine. The Maquinna’s crew then lowered No. 1 lifeboat, which rescued three people from the side of the Lorraine’s gas boat, one of whom was holding onto a gas drum. No more survivors could be found, though the lifeboat continued searching until 4:15 a.m., when the Maquinna’s stewardess, Mrs. Joan Leslie, reported that one survivor was suffering from a badly cut arm, and should see a doctor as soon as possible. With the lifeboat back aboard, the ship turned around and proceeded at full speed to the nearby missionary hospital at Esperanza, where the survivors were cared for by Dr. MacLean.

Of the MVLorraine’s seven passengers, four died and three were saved. Why such a small (and seemingly overcrowded) boat as the MVLorraine was on the water at that time of night is unknown. The Maquinna and her crew were not held responsible for the accident.

Later that year, a tragic incident occurred in far-off Toronto Harbour that had a considerable impact on the Princess Maquinna and other BC passenger ships. At 2:30 a.m. on September 16, 1949, a fire erupted aboard the passenger ship SSNoronic as she lay tied up to a dock in Toronto’s harbour. The ship regularly plied the Great Lakes as a tourist ship and her passengers were asleep on board. The fire claimed the lives of 118 passengers, most of them Americans. An inquiry recommended stricter fire regulations be imposed on all Canadian passenger ships. The cost of implementing these new regulations put such a financial burden on Canadian shipping companies, including the Union Steamship Co. and the CPR in BC, that many companies chose to tie up their older ships rather than spend the money needed to meet the new regulations.

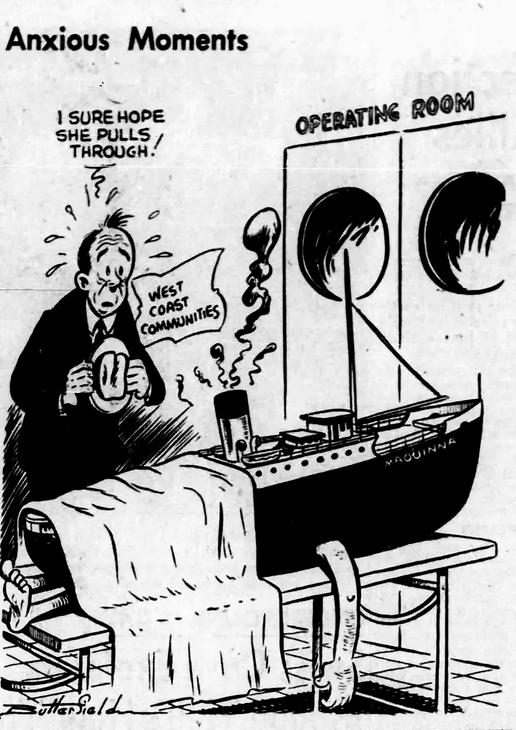

By 1952 the CPR head office took a long, hard look at its west coast route, assessing every aspect of the service in an attempt to decide what to do with the nearly forty-year-old Maquinna. As an immediate priority, the managers decided to assess the state of the ship’s thirty-nine-year-old boilers, suspecting they needed repairing or replacing. However, even before the inspection, a CPR official declared that “due to her advanced age it is not considered that it would be economically sound, or justified, to spend large sums of money on this ship.”205

The CPR also looked closely at the passenger and cargo numbers, reporting that “the Maquinna’s holds were on average only one quarter full; except during the summer tourist season, only 30 percent of her berths were booked. It was estimated that Queen Charlotte Airways were carrying 85 percent of the West Coast passenger traffic.”206 A flight on QCA from Vancouver to Tofino cost $21 and took forty-five minutes. In comparison the fare on the Princess Maquinna cost $19.45 and took two days.207

As for the declining freight statistics, the CPR noted that “Within recent years several fish packing operations have placed their own vessels in service on the west coast and many canneries have transferred their operations to Steveston—on the mainland at the mouth of the Fraser River—in order to centralize their activities. Fish boats, after unloading their product, are loading groceries, equipment, etc. for northbound voyages to their own establishments on the West Coast.”208 This new strategy by the fish-packing companies severely cut into the CPR’s bottom line on its west coast route.

Unquestionably, the continuing development of roads to various coastal communities also impinged on the business. In 1946 the new road from Port Hardy to Coal Harbour in Quatsino Sound had already forced the CPR to curtail service on the northern leg of the Maquinna’s ten-day run up the coast. In 1952 a reasonably good road had been established from Victoria to Shawnigan Lake over the Malahat, and by using connecting logging roads trucks could now transport groceries to Port Renfrew, further cutting into CPR revenues. With the potential of other roads being built, perhaps to Bamfield, Ucluelet and Tofino, the CPR realized that more roads would make “a steamship service on the West Coast extremely unprofitable.”209

Each year the CPR received an annual subsidy from the federal government to maintain the west coast service. In 1952 that amounted to $161,792. In an attempt to stave off the inevitable, the company made hopeful overtures to the appropriate ministry to see if that figure could be increased in order to continue the west coast service. The government, however, refused to increase the subsidy.

Cockroaches added to these woes. In the late 1940s and into the 1950s these unwelcome passengers infested the Maquinna. They appeared everywhere and hid in the dark recesses of the ship, prompting the ship’s stewards to devise unique ways of catching them. One of their most successful methods involved filling a glass tumbler with a little water and greasing the inside of the tumbler with some butter. The cockroaches climbed into the tumbler but the slippery butter prevented them from climbing out again. Soon they exhausted themselves in their attempts to escape, and drowned. The stewards emptied the tumblers each morning but some passengers “arose repeatedly in the night to empty the water tumbler and its victims out the porthole.”210 Since the cockroaches liked dark environs, regular passengers knew to lift the bedsheets and carry out an inspection of their bunks before bedding down. If they found some of the creatures they could call a steward to remove them.

Against this background of woes, the CPR announced that it would withdraw the Maquinna from service on Wednesday, September 24, 1952, to carry out a full inspection of her boilers, with no indication of how long the ship would be out of service. Her final trip before this inspection was slated to depart from Victoria on Thursday, September 18.

An article in the Vancouver Sun on Tuesday, August 10, 1952, quoted a CPR official as saying:

"The situation is that the vessel is old and her boilers have seen good service. But the cost of overhauling her and making her good as new again might cost more than the trade at present warrants. The cost of putting a better ship on this route would also not pay. West Coast trade has changed radically over the past years. The cargo there used to be paper, fish, timber and other big parcels, out and home. Now there is just a little to cover her bottom line only and you can safely say the ship is running at a loss. The Maquinna was formerly a good passenger ship. Everybody using the West Coast traveled in her. Now mostly they fly. You can’t pay the way of an empty ship. She is a magnificent tradition but unfortunately there is no money in tradition.211

"

Even if the Maquinna’s boilers could be repaired inexpensively, management realized that she was living on borrowed time and proposed three options for when she ended her career. They could abandon the west coast route altogether; replace the Maquinna with the Princess Norah on a permanent basis; or acquire a smaller vessel to replace the Maquinna.

The announcement of the Maquinna’s imminent withdrawal from service prompted a flurry of responses from a variety of municipal, provincial and federal spokesmen. The Honorable Robert Mayhew, Minister of Fisheries, stated that he would support the building of roads to the west coast. “Money would be better spent on permanent roads rather than on annual shipping subsidies,”212 he told the Daily Colonist. Anticipating the loss of the Maquinna, Esquimalt MLA Frank Matthews wired Union Steamships asking it to take over the run left vacant if the Maquinna failed to pass her boiler test. Port Alberni put forward the idea that it would make a much better terminus for a new service than Victoria, saying this would cut a couple of days off the schedule. Clo-oose residents resubmitted their plan presented to the provincial government some twenty years earlier, asking for a road to be built to their community, and Tofino’s president of the Chamber of Commerce, Tom Gibson, declared Tofino had been promised a road for fifty years and “now was the time to get on with it.”213 He added that a road would cost about $1 million and would be paid for in ten years, given that the CPR received a subsidy of over $100,000 a year to run the service. “The whole economy of the West Coast is at stake,” said Mr. R. Barr, a member of the Tofino Board of Trade. “We are facing an intolerable situation. We must have steamship or highway connections in order to survive.”214 It would be another seven years before a rough gravel road finally opened in 1959 connecting Tofino with Port Alberni.

Although her final trip was scheduled for September 18, 1952, the good ship Maquinna’s final trip up the west coast actually occurred some weeks earlier. She left Victoria on August 26 and safely arrived at Chamiss Bay in Kyuquot Sound (which by then had become her northern terminus) on August 29. She departed on the same day, disembarked forty-two children returning to school at Kakawis, loaded six tons of fish at Clayoquot, held an emergency boat drill at Port Alberni, and arrived back in Victoria at 6:33 p.m. on August 31. She then proceeded to Vancouver via the Gulf Islands, arriving at 6:30 p.m. She departed Vancouver at 3:50 p.m. on September 2 and arrived back in Victoria at 3:20 a.m. September 3. A very routine and uneventful trip.

On September 4, with forty passengers and cargo loaded for what was intended to be her second-to-last trip, “Old Faithful” cast off from the Belleville Street wharf at 12:17 a.m. However, a few minutes after leaving the dock her boilers gave out and could no longer produce enough power to drive the ship; she managed to limp only as far as the nearby BA Oil dock. The final entry in her log reads: “Sep 4 / 52. Arr. 12:50 BA Oil Dock. Port Landing.”

Captain Carthew assembled those passengers who had not retired for the night and informed them that the trip was cancelled. He told them that they were welcome to stay on board overnight and they would be served breakfast in the morning, but that they then must find their own way up the coast as best they could. The next day the crew unloaded the ship’s cargo and stored it in the CPR freight sheds, pending arrangements to send it up the coast. The mail was returned to the Vancouver Post Office, where officials began exploring ways to deliver it.

While most west coast communities could find ways to survive without the Maquinna on a short-term basis, isolated places like Kyuquot keenly felt the loss of “Old Faithful.” To bring in essential food supplies, the village arranged for fish company packer boats to carry in what they needed.

By the end of September, as a stop-gap measure, the CPR chartered the thousand-ton SSChilliwack from Frank Waterhouse Ltd.—a subsidiary of Union Steamships—to make a one-off emergency run carrying the Maquinna’s freight from her final voyage to coastal communities. The Veta C, another Waterhouse vessel, took over for the remainder of the winter. (The Norah was needed on other routes and so wasn’t available to fill in.) The Veta C provided no passenger accommodation and carried only freight, so the CPR continued looking for an adequate vessel that could take passengers as well as freight, thus filling the role of the Maquinna. In the years following, the small and ugly Princess of Alberni, the Northland Prince and the Tahsis Prince all filled in while folk on the west coast waited for the Maquinna to be repaired, or for roads to be built. Increasingly, passengers wanting to leave the west coast chose to make their way to Ucluelet and take the Uchuck, which sailed three times a week to Port Alberni, from where they would continue by road.

After a brief inspection of the Maquinna’s boilers, CPR management decided that repairs would not be undertaken. She remained tied up at the BA Oil dock until the spring of 1953, when she was sold to the Union Steamship Company and towed to Victoria Machinery Depot, where her superstructure and interior fittings were removed and sold off. Ivan Clarke of Hot Springs Cove purchased the stateroom keys. In April 1953 Captain J.O. Williams, manager of BC Coastal Steamships, a subsidiary of the CPR, presented the Maquinna’s bell to the jovial, pipe-smoking Rev. John Leighton, once the minister at St. Columba’s church in Tofino. He wanted it to call patrons to services at the Mission for Seamen in Vancouver where he then served. Several former Maquinna skippers attended the ceremony: R.W. Carthew, S.G. Hunter, P.L. Leslie, L.W. McDonald and Martin MacKinnon. At the same event, Williams presented the Maquinna’s binnacle, which held the ship’s compass on the bridge, to the Ucluelet Sea Cadets.

Captain Williams also ensured that the Bullen family received the Maquinna’s nameplate; the Bullen shipyard in Esquimalt had built the ship, forty years earlier. In a letter of thanks to Williams, J.W.F. Bullen wrote: “I proffer my most sincere and heartfelt thanks to you for making it possible to possess this memory of the old ship.” Also attending the ceremony was 17-year-old Melville Palmer, who had been born aboard the ship on April 18, 1936, when his mother was travelling south from Jeune Landing.

Later, a tug towed the Maquinna to Vancouver, where her engines and boilers were removed and her hull became an ore-carrying barge, renamed Taku. The name honoured the Alaskan inlet where her cargo would be loaded. Stripped down and with a modern steel crane installed, she joined four other ore carriers owned by Straits Towing, each carrying 2,000-ton loads of concentrated copper-lead-zinc ore from Taku to the smelter at Tacoma. The ore came from the Tulsequah mine in northern BC near the junction of the Tulsequah and Taku Rivers, having been transported some 30 miles (50 km) down to Taku Inlet on river barges. The sea-going barges off-loaded the ore from the river barges using their own cranes. Sometimes the Taku also collected ore at the mine at Britannia Beach on Howe Sound and took it to Tacoma.

The Taku continued this heavy and unglamorous work until 1962, when Acme Machinery Ltd. in False Creek, Vancouver, broke her up for scrap. An ignominious end for one of the best-loved ships in BC history.