Chapter 17: Tourism and Tragedy

Many may think of west coast tourism as a fairly recent phenomenon. Visitors have flocked to the west coast of Vancouver Island since the road to Tofino was punched through from Port Alberni in 1959, with even more following as the road improved, and yet more flooding in after the Pacific Rim National Park, protecting land on both sides of Barkley Sound, was established in 1971. The intense international coverage of the Clayoquot Sound logging protests of 1993 brought even more visitors, and since then they have come in ever-increasing numbers, making Tofino one of the leading tourist destinations in Canada. However, this urge to visit the west coast is far from new, and long pre

-dates our group of tourists disembarking in Victoria after their seven-day cruise aboard the Maquinna in 1924. The steamship companies serving the coast catered to this tourist market almost from their inception—they even helped to create it.

The opportunity to sail up the west coast of BC on an adventurous cruise had fired the imagination of travellers for decades before our 1924 trip. In 1888 California’s Pacific Coast Steamship Company launched the successful Alaska cruise industry with monthly voyages to southeastern Alaska from San Francisco, later joined by the Alaska Steamship Company trips from Seattle. Travelling the west coast of Vancouver Island had already become a recreational event, when the Canadian Pacific Navigation Company advertised in the Colonist in 1886 “that excursionists could travel to Clayoquot on the little steamer Maude.” Soon after the launch of the Maquinna in 1913, the CPR began tentatively promoting the attractions of the west coast for recreational travellers. Inspector H.W. Brodie hinted at the potential of the tourist trade on his inspection trip in 1918, and what the company could do to prepare for it: “If we decide to go in for additional tourist business during June, July, August and September, the service can be slightly improved. A few deck chairs are required, a phonograph for dancing, and an awning over the after deck. A bath room or two would require to be provided.”184

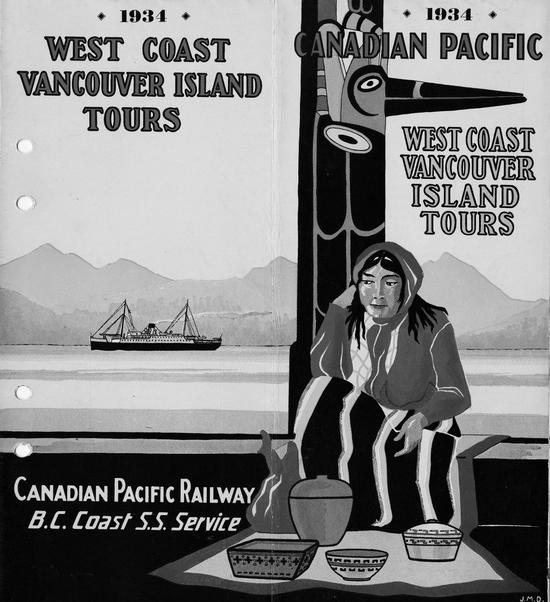

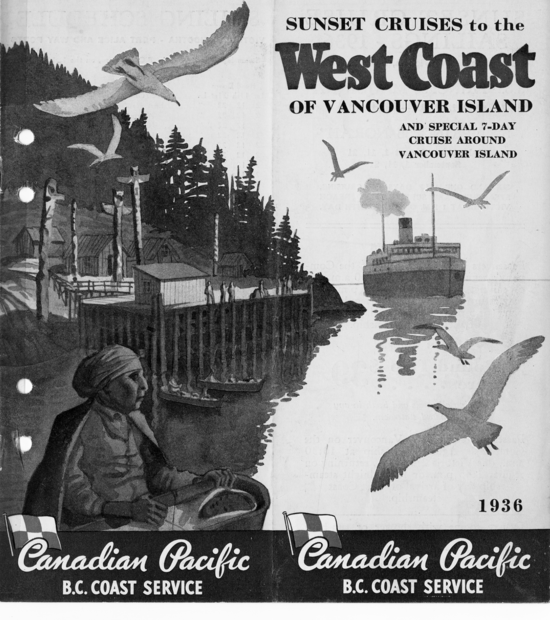

In the 1920s and 1930s the company went all-out to promote its Sunset Cruises, publishing vividly coloured brochures replete with images of totem poles, of First Nations people paddling canoes and of Indigenous women weaving baskets. Such marketing capitalized on the images and skills of people generally not allowed entry into the interior of any of the CPR ships on the West Coast run. Whether or not this was company policy, First Nations people routinely travelled up the coast on deck and in the hold, while white passengers had far better accommodation. This stark contrast seems to have generated scant reaction or comment at the time. Most tourists travelling on the Sunset Cruises aboard the Maquinna likely paid little attention to how the First Nations or Asian passengers were accommodated on the ships, being absorbed in their own adventure aboard. The cruises proved so popular that in the summer, locals living on the west coast often loudly complained of not being able to find accommodation on the ship, because all the staterooms were taken by tourists.

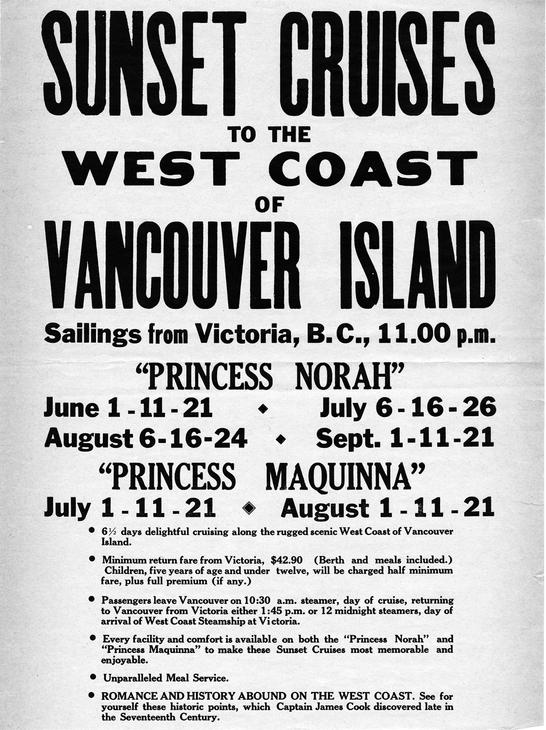

In the summer months during the 1930s and 1940s, tourists could take a seven-day cruise all the way up the west coast to Holberg in Quatsino Sound and back to Victoria or Seattle for as little as $39, including the cost of a berth and meals.

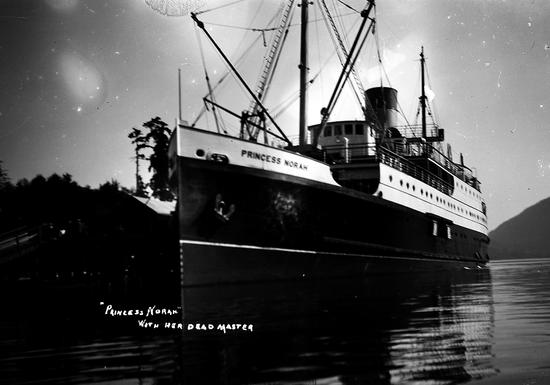

Popular demand for these cruises grew to the point that in 1928 Superintendent James Troup contracted Fairfield Shipbuilding Company on the Clyde, in Scotland, to build the Princess Norah—the last Princess ship Troup would build before he retired. Troup, who commanded the respect and affection of all, retired in September 1928, before the Norah’s maiden voyage in April 1929. Captain Cyril D. Neroutsos replaced him as superintendent. Known as “the Skipper,” Neroutsos was born in England and came to Seattle as a first mate on the Garonne, later moving to Victoria where he joined the Canadian Pacific Navigation Company before it was taken over by the CPR. Like Troup, Neroutsos had a keen interest in ship design and canny insight into the workings of coastal shipping.

The arrival of the Norah showed the commitment of the company to the tourist trade, hinted at by Inspector Brodie a decade earlier. And yes, the Norah would have deck chairs, awnings over the aft deck, baths and even showers.

The Princess Norah would be a thousand gross tons heavier than the Maquinna, but her length would be comparable, so she could continue using the existing wharves on the west coast. Both more manoeuvrable and more luxurious than the Maquinna, the Norah would run on the west coast of Vancouver Island in summer and to Alaska in winter. “Her larger superstructure housed more elaborate accommodation, which included a large observation lounge on the upper deck forward, and an attractive smoking room aft. The dining saloon could seat 100. Her 61 staterooms had 165 berths; they included four large deluxe rooms with private baths and 14 other cabins with showers.”185

Her inaugural voyage, with Captain Gillam in command, left Victoria on April 7, 1929, with the Governor General of Canada and his wife, Lord and Lady Willingdon, aboard. Also on this voyage were the Hon. Randolph Bruce, the Lieutenant-Governor of BC, and an array of dignitaries. Their arrival at the various stops en route caused a great stir among the locals:

"At Bamfield the residents turned out en masse to greet the representatives of His Majesty. Lord Willingdon was shown around the cable station and sent out cables to Sir Basil Blackett and Sir Campbell Stewart. At Ucluelet the Norah was invaded by school-children of three races, white, Indians, and Japanese who had been accorded a holiday for the occasion. Boatloads of Indians, in native attire, swarmed around the Norah as she came in. In Tofino, Indians in ceremonial attire, with painted faces and traditional headgear, tendered a formal reception to the vice-regal visitors at a colorful ceremony—which included the investiture of Lord Willingdon with the rank of Chieftain of the Clayoquot tribe. Numerous Indian baskets, carved Indian canes, and interesting totem poles of black slate, as well as two fish weighing more than 100 pounds each, were presented and which the passengers enjoyed for lunch the next day.186

"

The Norah took her passengers as far north as Port Alice before returning to Victoria.

The Norah’s second west coast trip proved to be Captain Gillam’s last. Then aged 65, he apparently suffered a fit of dizziness while on his way from his quarters and fell down a companionway, suffering fatal injuries. He died on board. When the sad news reached the various settlements on the west coast, everyone felt the loss keenly, for Gillam was loved and respected by all. “I remember my mother saying afterwards that he must have fallen because he was not yet used to the layout of the different vessel,” says Tony Guppy. “I was struck by the terrible irony: after all the years he had navigated one of the world’s most treacherous stretches of water, he died in a fall aboard a voyage ship.”187

“Captain Gillam, Purser Cornelius and the officers of the Maquinna were the best public relations group the CPR ever had,” wrote “Old Timer” in the Western Advocate in 1955. “Many times when the Maquinna would be unloading cargo all night, Capt. Gillam would organize a dance in the main saloon, furniture would be shoved aside and ‘joy’ would be unrestrained. Many a pleasant night I spent chasing ‘Madam Terpsichore’ [the Greek muse of dance] on the Maquinna.”188

“Captain Gillam’s calm authority and his good nature were as famous as his seamanship,” writes Margaret Horsfield in Voices from the Sound:

"He could control a group of drunken loggers with a glance. And, according to Mike Hamilton, the prospectors were even worse than the loggers: ‘Seldom did the coast steamer sail north or south without having aboard a number of miners and prospectors either coming or going. They were usually a rough, tough bunch, frequently hard drinkers with a vocabulary, when in their cups, capable of making anyone’s hair curl.’ But Captain Gillam could be counted on to keep the atmosphere on board his ship amiable, and he always ensured the well-being of the ladies on board.

Gillam served as captain of the Maquinna with dedication and unflappable calm throughout the 1910s and 1920s. Combined with his earlier service on board other vessels, he navigated the West Coast on the coastal steamers for some thirty years, witnessing at close quarters the changes in all the settlements on the coast... He saw the demise of sealing, the heyday of the West Coast whaling industry, and later, by the mid 1920s, its end. He saw small mines open and close and small sawmills flourish and fade. He saw the end of the hand logging era on the coast and the coming of mechanization, the beginning of the massive pilchard fishery, the beginning of the pulp and paper industry as mills opened at Port Alice, Alberni and Tahsis... He saw the scheduled stops along the West Coast steamer route increase year by year to serve the ever changing industries and settlements on the coast. Through their cargo, he knew every single development on the coast and all the people involved: the powerful Gibson family at their successful shingle mill at Ahousaht, the struggling Rae-Arthur family trying to operate a nursery garden at their remote Boat Basin homestead, the storekeepers, the schools and every one of the native Indians selling their baskets and handicrafts at Tofino and Nootka and Kyuquot.189

"

“Old Timer” also wrote about Captain Gillam’s ability to keep order aboard his ship, despite any “excitement or feverish haste” among the prospectors. “I don’t remember one bad incident happening during that time. I believe some of the bad boys took one look at Capt. Gillam and decided that if they played him it would be for keeps.”190

The Maquinna and Captain Gillam answered countless emergency calls to help save a life or help with a birth. He would hasten the Maquinna to the nearest of three hospitals, one at Port Alice, another in Tofino and the other at Port Alberni. His acts of kindness made him legendary on the west coast.

Port Gillam on Vargas Island, Gillam Channel in Esperanza Inlet and the Gillam Islands in Quatsino Sound all bear Captain Gillam’s name. He lies buried in Ross Bay Cemetery in Victoria.

Captain Robert “Red” Thompson, “thickset and broad shouldered, a ruddy complexion beneath a head of hair that was once red but is now mellowing to white,”191 took over as captain of the Maquinna following Gillam’s death. From the Shetland Islands, where he worked with his father from the age of 14 on sailing schooners fishing in the North Sea, he came to Canada in 1898, where he joined the Canadian Pacific Navigation Company as an able seaman. Later he joined the Canadian Pacific Coast fleet and served as an officer or captain on twelve of its fourteen passenger ships. In summer, when the Princess Norah returned to the west coast for the tourist season, Red Thompson took over its captaincy, and William “Black” Thompson—no relation—became skipper of the Princess Maquinna. Black Thompson had been captain of the Princess Charlotte and Princess Elaine prior to working on both the Princess Norah and Princess Maquinna.

Red Thompson would continue as captain of the Maquinna—off and on—until he “swallowed the anchor” and retired in 1944. He became a familiar and well-liked figure to all who sailed with him, earning him the title of “West Coast Skipper.” Subsequent captains of the Maquinna included Black Thompson, Martin MacKinnon, Leonard McDonald, Ralph Carthew and Peter Leslie.

Over the years, the Princess Maquinna carried a wide variety of passengers and a great deal of unpredictable cargo. For the tourists aboard the Maquinna and the Norah, watching the deck crews carefully winch up and off-load the huge variety of cargo from the ship’s holds at their various stops proved an endless source of fascination.

The Daily Colonist reported in March 1925 that the Maquinna was taking a consignment of muskrats on her trip north. “They were trapped along the Fraser River, and are being shipped up the west coast to be put ashore at Quatsino Sound, where it is hoped they will multiply and eventually provide a lucrative fur industry for Victoria.”192 Another time, a horse found its way aboard the Maquinna, not into one of the holds or onto the foredeck, where livestock usually travelled, but into a cabin. “The horse was snuck aboard one night while the ship was in Victoria,” Tom Henry relates in Westcoasters. “The culprits led the nag, head first, into the cabin, then departed and shut the door. When an unusual stink led a crewman to the cabin, there was turmoil. Any thought of reversing the horse out of the cabin was abandoned after a few bone-shattering lashes with its hooves. In the end, the cabin wall was cut away and the horse let out.”193

People on the west coast relied on the Maquinna to deliver their standard household supplies. “We used to get stuff from Woodward’s in Vancouver,” says Ucluelet’s Margaret Warren. “My mother would send her order to the CPR Office in Victoria and the Maquinna would go to Vancouver and pick up everyone’s orders from Woodward’s. The Maquinna charged only $2–$3 freight for shipping 10–11 boxes—a month’s supply. It didn’t matter if you were short of money, you’d just pay the next time.”194

Johnnie Vanden Wouwer tells the same story, from Bamfield:

"About once a month, we used to get an order of groceries on the Maquinna, around $10 or $20 worth, from Woodward’s in Vancouver. You’d get butter that way, in bulk, fourteen pounds of butter. And Peanut butter and honey, too, in big containers. Woodward’s own brand. We knew when the boat was coming, of course, and we’d row over there to the Cable Station and sometimes it came during a storm. And hundred pound sacks of chicken wheat, I’ll never forget them!195

"

Even though there were few roads in west coast communities, residents with extra money still bought cars and other vehicles that had to be carried up the coast on the Maquinna. In order to load them, the Maquinna’s crew devised special slings to hoist the vehicles on and off the deck and in and out of holds. “We copied those slings,” says David Young, former skipper of the Uchuck III, the coastal freighter that still operates out of Gold River. “It was a system of bars that locked around the front and back wheels of the vehicle and a cage affair hanging from the cargo hook with wires in all four corners that fastened onto hooks on the outside ends of the bars... Those slings are still being used on our boat to this day.”196

Even today tourists travelling aboard the Uchuck III and the Frances Barkley on the west coast continue to be fascinated by the off-loading of cargo, just as the tourists aboard the Maquinna and Norah were a century ago.