Chapter 18: Wartime on the West Coast

In August 1914, at the outbreak of World War I, the PrincessMaquinna carried many west coast volunteers to Victoria on the first leg of their journey to the battlefields of Europe. Many were Britons who had recently arrived as settlers, and they rushed to defend Britain and the Empire. They enlisted from Quatsino, Vargas Island, Tofino, Ucluelet and nearly every community on the coast. Many of them would never return, leaving widows and children. Clo-oose was particularly hard hit, suffering eleven casualties of the thirty-one who joined up. The tiny community held the distinction of having the highest rate of enlistment per capita of any community in Canada.

Twenty-five years later, on September 10, 1939, when Canada declared war on Germany to begin its participation in World War II, the announcement did not bring the same rush of west coast enlistment. Canada’s attachments to Britain and the Empire were no longer as strong as in 1914.

Everything changed on December 7, 1941, however, when Japanese forces attacked the US Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, 2,300 nautical miles (4,200 km) to the west of Vancouver Island. Almost overnight a sense of panic hit the coast of British Columbia. Suddenly the Canadian government and the people living on the coast realized how unprotected they were from a potential Japanese attack. Only two Canadian naval vessels and a few ancient aircraft stood ready to defend the whole of the West Coast of Canada from a Japanese invasion.

Canada’s Western Air Command immediately began upgrading its amphibious air base at Ucluelet so the outdated Stranraer and Shark “flying boats,” as the military called them, could better patrol the Pacific looking for submarines and possible invasion fleets. Construction also began on a new amphibious air base at Coal Harbour in Quatsino Sound. As well, work began on a wheeled aircraft base at Tofino to enable more, and bigger, aircraft to patrol the coast. The Tofino air base opened in October 1942. These large building projects brought many people to the west coast, but did not result in any notable increase in traffic for the Maquinna. The air bases in Ucluelet and Tofino relied on small, local freight/passenger vessels such as the Lady Rose and the Uchuck I to supply them out of Port Alberni. In 1941 a gravel road had been finished connecting Coal Harbour on Quatsino Sound to Port McNeill on the east side of the Island, where the Union Steamship Company’s vessels provided fast and frequent service to and from Vancouver, making the building of the air base at Coal Harbour a much more manageable project.

With these projects moving forward, many west coast fishermen joined the Fishermen’s Reserve, which became familiarly known as the “Gumboot Navy.” They took their fishboats to Victoria where the captains and crew underwent basic training, and the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) fitted the boats with .303 Lewis machine guns, wireless/telegraph sets and depth charges. The “Gumboot Navy” would patrol the coast throughout the war looking for suspicious activity and assisting the RCN whenever called upon.

Other westcoasters joined the Pacific Coast Military Rangers, also known as the BC Rangers. These loggers, trappers, prospectors and First Nations volunteers living in remote locations also kept an eye out for suspicious activities.

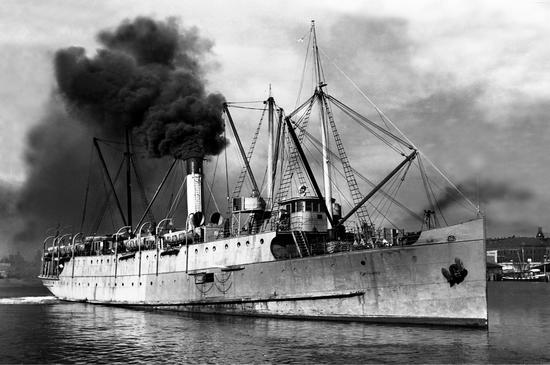

In early 1942, following the Pearl Harbor attack, the Maquinna sailed to Vancouver to receive a coat of wartime camouflage paint. Historian Jan Peterson records the recollections of crewman Geoff Wyman:

"The Maquinna arrived in Vancouver at 11 a.m. and was fully painted battleship gray in time to leave that evening. Unfortunately, the funnel was still hot when it was painted, so by the time it was out to sea, the paint had turned a bright silver making it more visible than ever. Wyman also remembered that a big gun [a 12-pounder] was mounted on the stern of the vessel. The idea being that the ship, which was faster than most warships, would steam away, and with the gun at the stern, could take shots at ships or U Boats pursuing it.197

"

After the initial flurry of wartime preparations, the Canadian government decided that the 23,000 Japanese Canadians living on or near the coast in British Columbia posed a security threat. Rumours circulated that some of the Japanese fishermen were members of the Japanese imperial forces, and would likely help the enemy in the event of an invasion of BC. Almost immediately after Pearl Harbor, during December 1941 and January 1942, the RCN seized every fishboat owned by Japanese fishermen on the coast and took them, or had them taken, to New Westminster. Then in February 1942, the Canadian government passed an Order in Council ordering all Japanese residents in BC be interned a minimum of 100 miles (160 km) from the coast.

For the hundreds of Japanese living in coastal Vancouver Island communities this upheaval caused tremendous pain and heartache. Over the years living on the west coast, they had become respected members of their communities; their children attended local schools; they were enthusiastic participants in local events and generous contributors to community endeavours. All of this made no difference. The order came in March 1942 that all Japanese residents must be prepared to leave their homes in forty-eight hours.

On the morning of March 15, 1942, twenty-seven Japanese people from Clayoquot and sixty-eight from Tofino assembled at the government wharf waiting for the Princess Maquinna, which did not arrive until late in the day. Looking out from her window over the crowded wharf, Katie Monks worried about the long wait they were enduring. “I said ‘Harold... there isn’t even a public toilet over there and the women and all those kids—could I go over and get some of them and bring them over here and at least give them a cup of tea?’ Her husband thought about it quite a while because it was bothering us. He finally said, ‘Well, I don’t think you should. Just look at it this way: they’re leaving but we have to stay.’”198

The Maquinna eventually arrived, looking “drab and ominous in her wartime grey,” and the Japanese embarked with their suitcases and bundles. “Not one of them looked back and not one of them waved goodbye... I never heard their departure discussed—ever—by children in my age group, or by the adults.”199

The Canadian government interned a total of 23,000 Japanese during World War II, including a number of veterans from the previous war. During the 1914–18 war 222 Japanese Canadians had fought for Canada; 54 had died and 11 won the Military Medal for bravery. The overall number of Japanese evacuees also included 231 Japanese from Ucluelet and 19 from Bamfield. They received their evacuation notice on March 20, 1942, five days after the Japanese of Tofino and Clayoquot had been taken away.

On the night of June 20, 1942, when a Japanese submarine—or perhaps some other vessel—shelled Estevan Lighthouse at the north end of Clayoquot Sound, the incident further heightened the fear of those living on the west coast. Even though the incident remains debatable to this day, its impact proved dramatic, bringing the war right to the doorstep of west coast residents and sparking widespread alarm. According to Neil Robertson:

"On that date a Japanese submarine, reported to be the I-26, surfaced 2 miles [3.2 km] off Estevan Point and fired about 25 rounds of 5.5″ shells at the Estevan Point lighthouse. Most fell short, but some went over the lighthouse and into the village of Hesquiaht. At the time a number of rumors went around concerning the incident. There were reports of other ships in the area at the time including Navy ships. One account was that the shells were fired by a US Navy ship and another was that it was a Canadian Navy ship, ordered to do so by the Prime Minister, W.L. Mackenzie King, in order to stir up the population and get support for his conscription policy.200

"

Various theories and rumours spread about what really happened at Estevan Point. Heightened stories along the coast at times verged on the unbelievable, even comical. Tofino’s Bjarne Arnet served as a skipper in the Fishermen’s Volunteer Reserve at the time of the Estevan Lighthouse shelling and he received orders over his radio to take his boat out and intercept the submarine. On board he had three old Enfield rifles from World War I and a stripped down Lewis gun. Having been born and raised in Tofino he knew every shoal, rock and sandbar on the coast, but decided to take no chances on this mission. “The next thing you know,” recalled a fellow Fishermen’s Reserve member, “Esquimalt got a message from Bjarne that they were ‘aground on a sandbar!’ No way was he going after a sub equipped like that!”201

Neil Robertson recorded another funny story of the Estevan Lighthouse incident that possesses all the elements of a good west coast yarn—without a shred of evidence to support it. Unsurprisingly it involves the indomitable and mischievous Gordon Gibson and the Princess Maquinna. “Early in the war a gun had been mounted on the Maquinna and a Royal Canadian Navy gunner was posted to the ship to man it and train some crewmembers in its use. The story goes that Gordon Gibson was aboard and had been partying with some friends. While off Estevan Point he and his friends fired the shots from the deck gun. Some years later Mr. Gibson was questioned about the incident at his Maui Lu Resort on Maui and he vociferously denied it. There is no mention of the incident in the Maquinna’s Log.”202

Throughout the war the Maquinna continued her faithful service on the west coast, camouflaged in her grey paint. Despite the war, her work carried on normally, back and forth, up and down the coast, with occasional forays to Vancouver. A few samples from the CPR files indicate some of her more notable wartime moments.

"Oct. 27th / 1940. David Beatty of Estevan Pt. B.C. embarked on this ship as passenger at Ahousat B.C. about midnight October 26th 1940, and was berthed in Room No. 27. He said he was not feeling well and asked for tea and sandwiches in his room. At about 3:45 am the night steward reported him dead in his room. The Provincial Police from P.M.L. No. 14, which was in port at the time, took charge of the remains. R. Thompson, Master.

Oct. 23 / 1941, 6:45 am. 1st Narrows, Vancouver Harbour. Outbound for Victoria, collided with West Vancouver Ferryboat Hollyburn inbound through first narrows in dense fog. Both ships were proceeding dead slow and had only a few passengers. Only damage was to the railings of the Hollyburn. W. Thompson, Master.

Jan. 22 / 1942, 6:39 am. Ship touched bottom in Alberni Inlet in Lat. 49–09–21N Long. 124–45–27W in dense fog. No damage. R. Thompson, Master.

Oct. 3rd / 1942, 11:15 a.m. On arrival at Vancouver on Oct 3rd, city detectives boarded the ship and arrested Robert Gerrie, aged 20, Canadian, Messboy, and Norman R. Woodland, aged 21, Canadian, night Saloon man, charging them with theft committed ashore. Joined 24–9–42, taken off 3–10–42. R. Thompson, Master.

Nov 25 / 1942. Vilko Virta, age 51 years, native of Finland and of unsound mind was brought on board by Constable D.H. Horace, B.C. Police at Ucluelet B.C. about 9:00 pm November 25th. They were assigned Stateroom No. 16. On arrival at Port Alberni B.C. at about 3:30 am Nov. 26th, he was found apparently dead by the constable in charge of him. Dr. Hilton, coroner, was summoned and pronounced the man dead by strangulation. The body was landed at Port Alberni in care of B.C. Police. R. Thompson, Master.

Jan. 27 / 1943. While working cargo in No. 2 hold at Zeballos about 1:30 pm, Stephen B. Bubel, seaman, sustained a broken leg. He was landed at Esperanza Hospital and left there in charge of Dr. McLean.

Jan. 14th / 1945. 10:48 pm engines stopped a/c [aircraft] report by two RCAF airmen of seeing man leap overboard. Lifebuoy and light thrown overboard. No. 3 lifeboat cleared. Ship maneuvered around lifebuoy endeavoring to pick up man in searchlights.203

"

Another wartime incident of note, reported by Hugh Halliday, appears in an article in the Legion magazine of April 25, 1995. “On December 18, 1943, personnel at No. 11 Radio Detachment (Ferrer Point, on the northwest coast of Vancouver Island) saw shells splash close to their unit and reported they were under attack.” Panic ensued and aircraft from Coal Harbour and Tofino scrambled to investigate, but only found two small fishing vessels near the area of the reported incident.

"Six hours after the reported shelling, the Seattle office of United Press was telephoning Western Air Command headquarters about reports of Vancouver Island being bombed. It was learned that the SSPrincess Maquinna, passing five miles [8 km] away, had undertaken some 12-pounder gunnery practice, firing toward what the crew took to be an uninhabited shore. The ship’s captain claimed his gun crew had only fired two heavy rounds; those on the receiving end claimed there had been anywhere between nine and twenty shell splashes. The presence of a radar site was, of course, a closely guarded secret, apparently even to the Maquinna.204

"

In August 1942 Allied forces recaptured the Solomon Islands and began “island hopping” toward Japan. As that campaign progressed, the threat of a Japanese attack on the West Coast slowly dissipated. Nevertheless, people remained vigilant; planes from the various airfields continued their lonely flights out over the Pacific and the “Gumboot Navy” continued patrolling coastal waters. Despite the lessened threat of invasion, the people on the coast, like all Canadians, continued living with the limitations of rationing and blackouts at night. Eventually, the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki finally ended the war on August 15, 1945. Shortly afterward, the Princess Maquinna sailed to Vancouver to be repainted, returning her to her more familiar peacetime colours.