Chapter 1: Casting Off

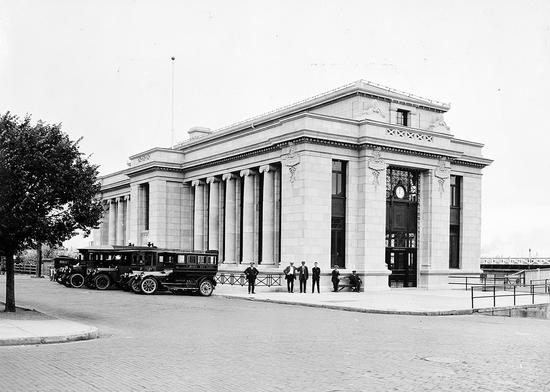

In the summer of 1924, as the 11 p.m. departure time of the SS Princess Maquinna nears, the new and imposing Canadian Pacific Steamship terminal on Belleville Street in Victoria bustles with activity. Locally known as the “Temple of Poseidon,” and designed, like the nearby Empress Hotel and British Columbia Legislative Building, by noted architect Francis Rattenbury, the terminus had opened just weeks before. Taxis roll up and streetcars disgorge fares, as others walk to the terminal carrying bags and belongings. Businessmen, loggers, cannery workers, mothers carrying newborn babies, families, priests in cassocks and nuns in habits, First Nations folk and tourists all make their way inside to the ticket office. Everyone is heading up the coast aboard the ship, sometimes referred to as the “Ugly Duckling” or the “Ugly Princess” but most often, and lovingly, called “Old Reliable” or “Old Faithful.” During her seven-day voyage up and down Vancouver Island’s rugged and dangerous west coast, the Maquinna will stop at up to forty ports of call. Those with means buy first-class berths in one of the ship’s fifty staterooms; others choose the less expensive second-class option, which has them sharing a four-bunk cabin with fellow passengers; others simply opt to sit in the ship’s main lounge for the trip. “Indians and Orientals”—as they are called in the CP fare schedule at this time—pay half the first-class fare, but are forced to remain outside on the forward deck.

With tickets in hand, the passengers, some accompanied by friends who have come to see them off, walk through the ticket office and make their way onto the ship to be greeted by ship’s officers, stewards and stewardesses. As the passengers board, stevedores and the ship’s crew load mountains of freight into the Maquinna’s three cargo holds—two forward, one aft. Some of that cargo, such as wooden boxes full of groceries, sides of beef, fruit, vegetables, bits of machinery, furniture, construction material, coils of rope and wire and empty wooden barrels, the crew load through the 2-metre-high by 2.5-metre-wide (6′ 2″ by 8′ 9″) cargo doors set in the ship’s side. Inside the hold, the deck hands and the ship’s purser, clipboard in hand, sort the tons of goods, moving the various items around the cargo deck using solidly built Fairbanks-Morse railway dollies and stout ropes to secure various items to ringbolts set into the hold’s sides. The crew places all cargo so it will come out at the various ports of call in the reverse order to which they loaded it, following the maxim “first on, last off.” Amid all the hustle and bustle, dogs, tied up in the forward hold, bark and howl, adding to the cacophony. On the forward outer deck, larger and more awkward items, such as lumber, large pieces of machinery, engines, oil, gasoline and kerosene drums, bales of hay, cows and horses, sometimes even an automobile, are lifted from the dock using the ship’s derricks, capable of lifting eight tons. Special hooks and slings come into play to lift awkward items using the ship’s three pairs of steam winches, manned by long-time expert winchman “Shorty” Wright. Johnnie Vanden Wouwer, of Bamfield, recalled that once “They took a troller [a fishboat] up on the bow deck; a thirty foot troller for Kyuquot!”1 Back inside, the purser stores the more precious cargo such as mail, small parcels and fragile goods under lock and key in the special mailroom, located near the bow inside the forward cargo hold.

From the moment passengers come aboard the SSPrincess Maquinna, the ship’s layout encourages them to mingle with their fellow passengers and the ship’s crew. “There wasn’t anywhere to go, everyone had to be friendly.”2

When entering the ship, they step into a space serving as the ship’s lobby, a gathering place with couchettes of green leather built around the walls. Here, those who do not have cabins will spend the journey. The lounge also holds the newsstand, selling newspapers and confectionaries, as well as a ticket office, where those who board the ship at various ports of call after it leaves Victoria will pay their fares. An upright piano also stands in the lounge ready for those who can play to entertain their fellow passengers. Often impromptu singsongs and dances break out. This ship’s lounge represents the main congregating area for the voyage, but people also gather in the nearby smoking room and in the dining room, just down a passageway. Travelling on the Maquinna is akin to boarding a local bus. People know each other because the west coast communities from which many of them come are so small that most everyone knows everyone everywhere, if they are local. Familiar faces are not hard to find. Victoria’s Daily Colonist regularly reports on the ship’s arrivals and departures, what cargoes she carries, and also lists most of the passengers who travel on her. Here is a typical passenger list from November 2, 1913:

"When Maquinna slipped away from the Belleville Street wharves last night she was again in command of Capt. Gillam. Among passengers who sailed were: H. Baines, G. Davis, Mrs. William Clancy, H.B. Round, F.V. Longstaff, H. Mahoney, C.B. Whaley, W.S. Taylor, Robert Wallace, M. McDonald, J. Hogan, W. Jones, William Marshall, G. Tucker, C. Tucker, A. Haywood, M. Parnwill, L. Duckett, A. Luckovich, R.C. Lumsden, A. Johnson, Mrs. F. Baker, Mrs. G. Baker, J.C. Wright, Mr./Mrs. Bridger, Mr. Halkett.3

"

Once aboard, passengers with cabin bookings search the labyrinth of passageways for their cabins, and, if unfamiliar with the ship’s layout, one of the ship’s stewards or stewardesses will help direct the way. First-class passengers seek out the fifty staterooms, while second-class ticket holders share cabins on a lower deck. If all the cabins have been booked, second-class passengers sit in the lounge for the trip, while First Nations and Chinese or Japanese travellers, with their “deck class” tickets, remain outside on the forward deck, sometimes creating makeshift shelters under the companionways in bad weather. If the weather turns particularly foul, the captain might allow them to shelter in the forward cargo hold.

Five minutes before 11 p.m. a bell warns visitors that they should depart. At precisely 11 p.m. the ship’s distinctive whistle sounds and, on the bridge, Captain Edward Gillam, the experienced ship’s master, orders the hawsers to be let go and directs his helmsman to begin easing the Maquinna out into the confines of Victoria’s tightly enclosed inner harbour. Captain Gillam knows Victoria Harbour and the west coast as well as anyone. He arrived on the west coast from George’s Bay, Newfoundland, in 1879 at age 16. At first he sailed on sealing schooners but later became a deckhand on the SSQueen City, rising to become its master before becoming captain of the SSTees. Familiar with the Maquinna’s sharp whistle and knowing its significance, many Victorians in their houses in Fairfield and James Bay knowingly announce to whoever is within hearing: “There goes the Princess Maquinna!”

Years of experience tell Captain Gillam exactly at what compass point he should order his helmsman to set the rudder, and for exactly how many minutes and seconds at a certain number of propeller revolutions the ship needs to back away from the dock. When the ship reaches that precise point in the constricted harbour, the helmsman changes course and the Maquinna’s bow slowly turns, aiming for the narrow gap between Laurel and Songhees Points. Once through the gap and out of the inner harbour, Gillam signals the engine room to increase steam and the ship picks up pace, heading toward more open waters. In order to run the ship Captain Gillam has four officers and sixteen ratings employed in the Deck Department, three in the Pursers’ Department, three engineers and eight ratings in the Engine Room Department, three stewards/stewardesses, twelve waiters and bus boys, and five cooks—all Chinese—in the Stewards’ Department. For managing this crew of fifty-four, keeping his vessel running efficiently and having the health, safety and welfare of his passengers resting on his broad shoulders, Captain Gillam earns the princely sum of $250 per month.

Once through the Laurel/Songhees Point gap, the Maquinna passes out of the harbour and past Fisgard Lighthouse, off its starboard bow. Built in 1890, British Columbia’s oldest lighthouse stands at the entrance to Esquimalt Harbour. Twelve years earlier, inside that same harbour, the SS Princess Maquinna first came down the ways of the BC Marine Railway Company shipyard, on Christmas Eve 1912. In 1913, soon after the launch, the BC Marine Railway Company, then known familiarly as Bullen’s yard, became Yarrows Shipyard. The construction and launch of the Princess Maquinna marked a hugely progressive step in the history of shipbuilding in British Columbia, particularly on the west coast of Vancouver Island, where strong, reliable ships had been in demand ever since the establishment of Fort Victoria by the Hudson’s Bay Company back in 1843.

Back in the 1840s and 1850s, sailing schooners primarily served the seaborne transportation needs of the earliest trading posts on the west coast of Vancouver Island. In 1874, thirty years after the establishment of Fort Victoria, only four traders lived permanently on Vancouver Island’s west coast: Fred Thornberg at Clayoquot, Peter Francis at Spring Cove in Ucluelet, Andrew Laing at Dodger’s Cove in Barkley Sound and Neils Moos at Port San Juan. When settlement did eventually occur on the outer coast in the 1880s and 1890s, in places such as Port Alberni, Ucluelet, Clayoquot and Quatsino, the need arose for a reliable, regularly scheduled shipping service to serve the growing population and industries. Into that breach, in 1883, stepped the Canadian Pacific Navigation Company (CPNC).

Steam-driven vessels, such as the ones the CPNC used, arrived in British Columbia fifty years earlier when, in 1836, the Hudson’s Bay Company contracted the Green, Wigram and Green shipyard at Blackwall, near London, to build the SS Beaver to serve the needs of the company. Two modest 35-horsepower engines powered her side paddles and drove the 102-ft (31-m) Beaver through BC waters for the next fifty-two years. She faithfully served as a freighter, tow-boat and even gun ship, eventually running aground near Stanley Park’s Prospect Point, near the entrance to Vancouver Harbour, in 1888.4 This modest beginning of steam-driven ships in BC led, in 1883, to the Hudson’s Bay Company combining its then four vessels—the Beaver, Otter, Enterprise and Princess Louise—with the Pioneer Line, which had dominated the river steamboating business, mainly on the Fraser River, for over twenty years. This amalgamation formed the Canadian Pacific Navigation Company Ltd., with the Pioneer Line bringing its four steamers (mostly paddlewheelers)—the R.P. Rithet, Western Slope, William Irving and Reliance—into the new partnership. Optimism soared within the new CPNC because of the impending extension of the Canadian Pacific’s transcontinental railway to Burrard Inlet, which surely would bring a huge increase in business, even though the CPNC, despite its name, had no financial connection to the Canadian Pacific Railway Company.

Within five years, the CPNC had established regular scheduled routes in the Strait of Georgia, the Fraser River and to northern ports on the mainland coast. Then in 1888 the company established its first bi-monthly service on the west coast of Vancouver Island when its SS Maude began a regular run from Victoria to Port Alberni and Barkley Sound. Originally a sidewheeler of only 113.5 ft (34.6 m) in length and 214 tons, this wooden-hulled vessel had been built on San Juan Island and had her 150-horsepower engine installed in Victoria in 1872. In 1884, a refit removed her engine and she became a coal barge, but a year later, with a new engine installed, she became a propeller-driven screw steamer powered by a compound two-cylinder engine.

For a number of years, the Maude made her bi-monthly trips up and down the west coast of Vancouver Island, and by 1896, three trips a month. In 1895, however, with more mining activity in Barkley Sound, the little Maude proved inadequate to handle the growing trade, prompting the CPNC directors to purchase the SSTees in 1896 to supplement and eventually to replace the Maude.

“The steamer Tees, which has been purchased (for $52,031.57) by the CPCN Co. to put on the west of Vancouver Island coast route, is a modern ship being thoroughly up to date in the matter of appointments, fixtures and machinery,” declared the Daily Colonist. “Built at Stockton-on-Tees in 1893 she is 679 tons... Her dimensions are given as: length, 165 feet, beam 26 feet, depth of hold 10.8 feet. The vessel’s machinery is also of the most modern description and capable of driving the vessel at a rate of 10½ knots. The engines are triple expansion, 95 [nominal] hp [horsepower] and last but not least... it includes an electric plant which lights the ship throughout.” Built of steel with a double hull, she could accommodate seventy-five or more people in “spacious cabin accommodation.”5

The Tees barely had time to make her inaugural run to Port Alberni in 1896 when news of the discovery of gold in the Klondike, which reached the outside world in the summer of 1897, led to nearly every available ship on the coast being diverted to carry men and materials to the Yukon. Realizing this extremely profitable opportunity, CPNC’s general manager, Captain John Irving, immediately assigned the Tees to the Yukon run and “On sailing nights many Victorians would gather and watch her load her cargo: horses, dogs, and hordes of bewhiskered miners.”6 In 1898, with the Tees sailing back and forth to the Yukon, the CPNC purchased the SS Queen City and salvaged the SS Willapa, which had sunk near Bella Bella. On hearing that the underwriters had declared the SS Willapa a total loss, CPNC’s manager John Irving sent the Tees and a salvage crew north to pump out the hull and tow her to Victoria. Once refurbished, the SS Willapa began working the west coast of Vancouver Island route, along with the SS Queen City, replacing the Tees while she served on the Yukon run.

The passengers on the CPNC ships, particularly those living on Vancouver Island, began voicing dissatisfaction with the haphazard operations of the shipping company. Displeasure grew even louder during the Klondike Gold Rush when the CPNC took many of its best ships from their normal routes to serve on that lucrative run. In 1898 the Victoria Board of Trade wrote to the president of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company, Sir Thomas Shaughnessy, asking him to consider having his company buy out and take over the CPNC. On January 12, 1901, articles in the Victoria and Vancouver newspapers declared that the Canadian Pacific Railway Company had taken over the CPNC (though its name and livery were in use for another two years). “The announcement will be hailed with great satisfaction on all sides,” declared the Daily Colonist.7

The CPR paid $531,000 to take over the CPNC and its fourteen ships. With the deal complete, the CPR transferred its very capable manager of the Kootenay Lake steamboat operations, Captain James W. Troup, to the coast to act as superintendent. Troup possessed a wealth of experience in shipping. His maternal grandfather, Captain James Turnbull, had been a sailing-ship master, and his father, Captain William H. Troup, had been a well-known riverboat master on the Columbia River. James also became a captain and a riverboat designer, attributes that gave him the necessary pedigree, acumen and experience to run the CPR’s new operations.

Born in Portland, Oregon, in 1855, James W. Troup began his career as a deckhand on one of his father’s riverboats on the Columbia River at age 17, and by 1878, at age 20, became master of his own steamer, the Wasp, and “soon gained fame as a daring and skillful swiftwater pilot.”8 In 1883 Troup came to British Columbia where he took command of the Canadian Pacific Navigation Company’s sternwheeler William Irving, running on the Fraser River between New Westminster and Yale, and later the sidewheeler Yosemite, sailing across the Gulf of Georgia between Victoria and New Westminster. In 1886 he returned to Oregon as superintendent of the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company, but six years later he returned to Nelson in the BC Interior to take charge of the lake and river steamers of the Columbia and Kootenay Navigation Company, which allowed him to not only build but design steamers specifically for that service. In 1897 the Canadian Pacific Railway purchased the Columbia and Kootenay Navigation Company, retaining Troup as its manager. The next year, with the Klondike Gold Rush in full swing, he headed that lucrative operation for his new employer, designing and building four sternwheelers for use on the Yukon and Stikine Rivers, to transport miners and their goods to and from the Yukon goldfields.

By 1901, with the gold rush on the wane, Troup returned to the Kootenay lakes just as the buyout of the Canadian Pacific Navigation Company occurred, and in the same year he moved to Victoria to become the manager of the new CPR coastal service. Once re-branding of the CPNC ships was completed in 1903 the CPR appointed Troup the superintendent of its British Columbia coast service. “For James Troup, the new British Columbia Coast Steamship Service was to be an all-consuming challenge for the remainder of his working life. He put his talents as a ship designer and his persuasive abilities to work immediately and convinced Canadian Pacific’s management to build some of the finest coastal liners ever seen on the Pacific Coast.”9

Troup took over a fleet of fourteen vessels that had come to the CPR from the CPNC, ranging in size from 175 to 1,525 tons, and in age from a few weeks old to forty years. He immediately began planning to upgrade and to add to this fleet. At the time of the takeover, the CPR already ran its elegant, ocean-going Empress fleet of stately liners, such as the Empresses of Canada, Britain and Japan, across both the Atlantic and the Pacific. With these ships foremost in his mind, Troup determined to create a fleet of smaller, but no less opulent, “pocket liners,” or Princess ships, for the BC coastal service, and to name them after princesses of European royal families. Over the next decade he would design and oversee the building of the first nine of these vessels, which would eventually make up the nineteen-strong fleet of Princesses.

"Although not a qualified naval architect, Troup had a vast practical knowledge of ships and shipbuilding. He had had a hand in the building of many river and lake steamers, and he had also helped design the big and luxurious screw steamer Victorian intended originally for the Seattle–Victoria run... and for the years that he was responsible for the Princesses he brought into being a long succession of remarkably successful vessels. Each bore very clearly the stamp of his ideas and his experience. Many of the technical details were worked out by naval architects, but Troup had talents that sometimes enabled him to confound the experts. He had, for example, a singularly sharp eye for the lines of a hull, and once detected a serious error in the calculations of a famous shipyard simply by carefully examining the half-model of the vessel under design.10

"

Troup would dominate every detail of the CPR’s west coast fleet’s operations over the next twenty-seven years, ensuring that people living on the west coast would have the finest service and ships to serve them. Of all the CPR ships in the fleet, none would prove finer or more beloved than the SS Princess Maquinna.