Chapter 5: Boat Landings

Steaming northward from Port Renfrew, after an hour and a half the Maquinna reaches the first of the three most tricky and perilous stops on the vessel’s entire journey. Carmanah Lighthouse, Clo-oose and Nitinat all require boat landings, meaning there is no dock to tie up to and passengers and goods have to be off-loaded into rowboats or canoes in open water while the ship heaves to—or holds its position—against the incoming waves. Before this can occur, Captain Gillam carefully assesses the weather, the tide, the Pacific swells and the overall conditions in order to decide whether to stop at each of these places or whether to carry on and hopefully make a stop on the Maquinna’s returning southbound journey instead. Should the conditions prove fine, the ship heaves to as close as possible to shore, turns her bow out to sea to meet the oncoming swells and drops anchor, all the while keeping her engines ticking over with enough power to hold her in position. On one occasion at Clo-oose the Maquinna bumped her keel on the sandy seabed, whereupon Captain Gillam did not even wait to haul anchor, but let it go, chain and all, and headed out to sea.

At the Carmanah Lighthouse, built in 1890 and run by six people, small rowboats make their way out from Carmanah Point, on which the lighthouse sits, to the freight doors at the side of the Maquinna. There, the goods for the light station are precariously off-loaded into the bobbing boats and rowed to the bottom of the headland where they are loaded onto a gasoline-powered trolley atop a tramway to be taken up to the lighthouse.

Prior to the Maquinna’s arrival on the west coast, when the SSTees served this route, W.P. Daykin held the position as Carmanah lig htkeeper from 1891 to 1912. His daily log contains many stories of rowboats being swamped or overturned, ruining precious supplies. He “expressed frustration when foodstuffs—especially his supply of liquor—was carried back and forth several times, because of bad weather, before it could be landed. Since there was no refrigeration on the small steamer, his meat proved unfit for human consumption by the time it eventually landed—and the lightkeeper bore the financial loss as well as the loss of his food.”47 On one occasion, with the weather too stormy for the supply steamer to call for a full month, Daykin finally received his forty pounds of bacon, to find it so ripe and “ALIVE” he sent it back on board. So frustrated did Daykin become with such misadventures and the loneliness of Carmanah, that he reputedly was consuming a bottle of Scotch a day for “medicinal purposes.” Despite his drinking, however, he continued conscientiously doing his job until transferred to Macaulay Point Lighthouse at the entrance to Victoria Harbour in 1912.

Half an hour and 4 nautical miles (7.5 km) north of the Carmanah Lighthouse, the Maquinna heaves to off Clo-oose, which means “safe landing” in the language of the local Ditidaht people. It is anything but a “safe landing” site for a sizeable steamer. Clo-oose lies exposed to the force of wind and waves coming across the vastness of the Pacific Ocean, making it an impossible place to build a dock. It is the kind of place more beloved by surfers than by ships trying to disembark people and goods onto an open shoreline. Despite the difficulty of access, Clo-oose possesses a long and interesting story of settlement, ranking it among the most improbable pioneering stories in a province noted for such ventures.

An economic boom before World War I saw a rush of buyers purchasing raw land all over the province of British Columbia. Local newspapers were crammed full of advertisements offering lots for sale, sometimes in the most unlikely locations. From the late 1890s immigrants had arrived in Canada from overseas in the thousands, in a land-rush bonanza initially fuelled by Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier’s federal government offering 160 acres of free prairie land to lure people to come and settle that vast and harsh environment. Laurier’s plan succeeded in attracting more than 1.5 million settlers to put down roots on the prairies between 1896 and 1911. With robust economic times seeming to last forever, people looked for similar opportunities to buy cheap land in other parts of Canada. Many arrived having little idea of what they would face; this was certainly so on the west coast of Vancouver Island, perhaps the most dramatic example being at Clo-oose.

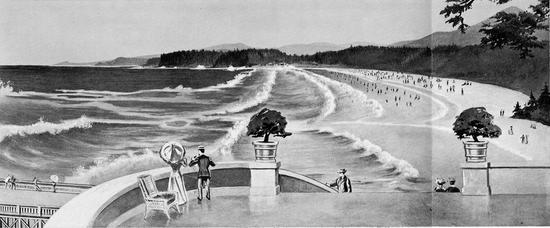

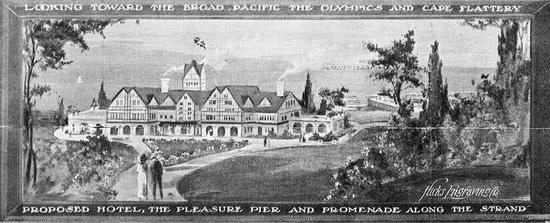

Into this milieu stepped a number of unscrupulous real estate developers associated with the Victoria firm of Monk, Monteith and Co. Ltd., “one of the largest and most influential real estate and insurance firms in Victoria.”48 A group of these men incorporated the West Coast Development Company in 1912 with the aim of developing a seaside resort community at Clo-oose, boasting that it would become “Canada’s Greatest Pleasure Resort.” The company printed attractive, colourful thirty-page brochures complete with stylized graphics and photographs to lure prospective buyers, distributing their propaganda far and wide. Lavish proposals for development promised a splendid three-hundred-room hotel—not unlike the CPR hotels at Lake Louise and Banff Springs—featuring tennis courts, croquet and bowling greens, and a golf course, as well as offering to stage light operas and vaudeville acts during the summer months. In addition it touted a sandy beach 9 miles (14.5 km) long—a considerable exaggeration—from which the driftwood would be removed, plus medicinal springs, incomparable salmon and trout fishing, and hunting without parallel. Amazingly, they also promised that there were absolutely no flies or mosquitoes. As an added incentive, the promoters offered a $10,000 cash prize and a $1,000 bungalow to the buyer who came up with a name for the resort.

Once incorporated, the company purchased lots 56, 57 and 70 in the Renfrew Land District, which it subdivided into 5,000 lots of 33 by 66 ft (10 by 20 m)—which was even smaller than the average city lot—and put them up for sale at $150 to $200 per lot. Road allowances were cleared and trails were made to provide temporary access to the lots until such time as roads could be completed. The old SSTees would initially provide transportation from Victoria, but the brochure promised she “... would shortly be succeeded by a magnificent new steamer called the Princess Maquinna.”49 The developers even promised a Canadian National Railway spur line—backed by the provincial government—to connect the development to Lake Cowichan in the middle of the island. It would never be built. They even petitioned the BC government to change the name of Clo-oose to Clovelly. That also never happened.

An artist’s sketch, drawn for the promoters, whose imaginations had run wild, depicted long wharves flanked by cargo ships, wide streets, fine buildings and a street railway fronting a magnificent white beach lapped by the sparkling blue waters of the Pacific Ocean.

Soon some two hundred settlers arrived and began establishing themselves temporarily in tents along the beach, while building more permanent log cabins for themselves and their families. Many of these settlers came from Britain, having fallen under the spell of the advertising campaign. They began by felling the enormous trees nearby and hauling them to the site. Few of these settlers had ever faced such a harsh or forbidding environment before, and were entirely out of their element. Angela Newitt, who came from England to Clo-oose as a three-year-old wrote: “Poor Daddy, I don’t know what he thought he was going to do in Canada. He had left a nice cushy job with Prudential Life in London, where his hobby was the Royal Horticulture Society and growing prize roses for the show. His passport to Canada described him as a ‘Gentleman Farmer’!”50

Some who arrived didn’t stay long enough to fight it out with the elements. “One family from Alberta, who came without any preliminary inspection direct to Clo-oose—sold up everything and saw all their goods going ashore by dugout from the Maquinna. The story has it that they asked for the city hall—they left on the return voyage abandoning most of their possessions.”51

The developers did build one edifice, the Bungalow Inn, where some of the newly arrived settlers stayed until they found their properties. “The Inn was a large dining room with a huge stone fireplace. There were no bedrooms. Most guests lived outside in tents, some of the larger ones with ‘camp-keeping’ facilities, and were served meals in the Inn. Those living inside the building lived in sections partitioned off by blankets. As one old-timer said, ‘You knew where you lived by the colour of the blankets’!”52

Some of the settlers took up farming, perhaps convinced by the promotional brochures that glowingly described “the Island’s rain forests as the last frontier of virgin soil... [where one] could grow potatoes the size of footballs, and corn as tall as trees...”53

The settlers fought off cougars and packs of feral dogs that attacked their livestock, as well as incessant rain and winds, occasionally finding comfort in parties, dances and social gatherings. One of the odder newcomers “used to dress in formal wear for dinner and entertain his guests on a player piano. In order to accommodate them he built bleachers at one end of his large dining-room.”54

“Very little news of the outside world got through to us,” writes Newitt. “The boat rarely called in winter, and Mother said that we didn’t know there was a war on [World War I began in August 1914] ’til the first boat arrived in the spring of 1915. As soon as this news arrived, most men... left to join up, my father amongst them.”55 Of the thirty-one men of Clo-oose who went overseas to fight in this devastating war, eleven died, including Newitt’s father. Clo-oose gained the distinction of sending more men per capita to World War I than any other place in Canada.56 Although late in joining the rush to go overseas, the men from Clo-oose joined hundreds of others from other small communities up and down the west coast of Vancouver Island who boarded the Princess Maquinna on the first leg of their journey to the battlefields of France and Belgium.

With the loss of so many men, the women of Clo-oose found it increasingly difficult to maintain themselves and their children in such an isolated location with no amenities whatever, ceaseless hard work, increasing loneliness and with no sign of the promised development coming to fruition. They began leaving for Victoria. When the soldiers returned in 1918 and 1919, those who made their way back to Clo-oose found hard economic times and very little work, even though following the war the Lummi Bay Cannery opened at the nearby mouth of Nitinat Lake, and the Nitinat Logging Company also provided some employment for a time. But the cannery closed in 1921, and yet more settlers gave up and left. Nevertheless some people did hang on, relying on the Princess Maquinna as their connection to the outside world, and as long as people remained, the boat landings continued, requiring the skills of the Ditidaht paddlers in their hand-hewn dugout canoes to transfer passengers and their goods to and from the shore.

The First Nations paddlers brought their canoes alongside the Maquinna’s open cargo doors at the side of the ship where a crewman, harnessed to the hull, readied loads of goods, preparing to lower them.

The dugouts manoeuvred alongside the rolling vessel and, at just that instant when the canoe was on top of a swell, the sling load was dropped into the canoe while it was fended off from the ship’s side. Passengers were unloaded the same way, females as well as males. They stood poised at the open freight door of the ship, ready to jump at the critical moment. If they jumped too soon they met the canoe as it surged upward on the swell and anything might happen; if they jumped too late, they had ten or twelve feet to fall to the bottom of the canoe as it sank in a trough.57

Sometimes, usually in calm weather, disembarking passengers could climb down a rope ladder to the canoes. Miss Hardwick, who arrived in Clo-oose in 1906, when her father came as a timber cruiser, relates that “one had to very carefully time their jump from the swinging rope ladder to the swaying canoe, it was, to say the least, a precarious mode of disembarkation and, more than once, ill-fated. Once [...] a missionary’s wife had had to swim ashore unaided when she missed her ‘step’ into a waiting canoe.”58

“Tourists marvelled at the way such frail craft were manipulated,” writes George Nicholson in Vancouver Island’s West Coast:

"Usually, the canoes were handled by ‘one old Indian with a short paddle,’ as a younger native squatted in the stern to catch the freight as it was tossed from the ship. Occasionally a passenger had to be taken ashore the same way and if it happened to be a woman, camera-armed tourists got a greater thrill. Watching the heavily-laden canoes go ashore was just as exciting, especially as they neared the beach where, regardless of how smooth the sea appeared to be, the swells always broke. More so when it was really rough and a ducking for someone and wet freight usually resulted.59

"

“Landing conditions were often not ideal,” writes R.E. Wells in There’s a Landing Today:

"The canoes would sometimes put off in rough seas, the residents determined to land whatever the ship had for them. A canoe could get caught under the heavy guard rail of the ship and before the paddlers could fend off, it would be flipped over with men and contents. Sometimes the flour, which had been ordered from town weeks before, would at the last moment get soaked. There was a time when a baby, being so well wrapped against the elements, was passed down from the mother and, in the hurry of the moment and with the rising and falling swell, was placed face down in the canoe. With the amount of water that the canoe had shipped, the poor little one was almost overcome.60

"

Drama over, the Maquinna ups anchor and heads out to sea, rounding Carmanah Point and steaming north once again. She will make other boat landings on her way up and down the west coast, at Kakawis, Refuge Cove and Hesquiaht, but none of these hold the peril, precision and sheer excitement of the two stops at Carmanah and Clo-oose.