Chapter 7: Bamfield

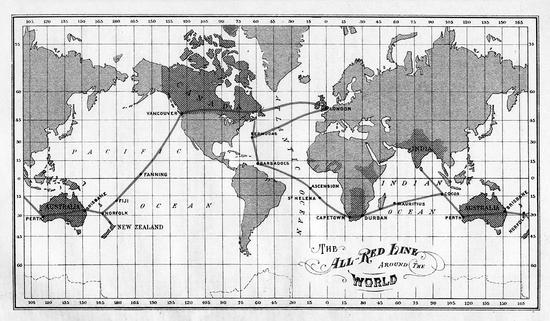

In 1879 renowned inventor and chief engineer of the Canadian Pacific Railway Sir Sandford Fleming put forward an extraordinary plan. He proposed that the British Empire should connect its farthest-flung colonies by establishing an empire-wide telegraph cable network. Existing telegraph cable lines already stretched from Britain to North America under the Atlantic Ocean and across Canada. Fleming now wanted to add a 4,000-mile (6,430-km) Trans-Pacific Cable extending all the way from Canada to Fiji, Australia and New Zealand. Because maps at that time usually depicted the countries of the British Empire in red, the new line bore the name “All Red Line,” signifying it was all-British and that in time of war, messages sent would be secure.

On November 1, 1902, Fleming’s vision became a reality, when the Trans-Pacific Cable linked Bamfield, on Vancouver Island’s west coast, with the telegraph station on Fanning Island, a small coral atoll in the mid-Pacific Ocean about 900 miles (1,450 km) south of Hawaii. From Fanning Island, another line connected to Sydney, Australia, and to Auckland, New Zealand.

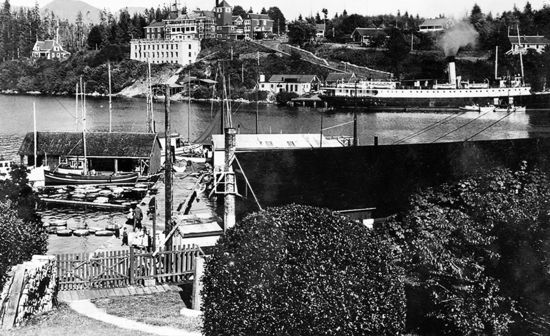

In 1901 the cable company built a three-storey timber building, which resembled a Canadian Pacific railway hotel, to house the telegraph equipment and the twenty operators transmitting messages on the All Red Line. BC’s most famous architect, Francis Mawson Rattenbury, who had designed the Empress Hotel, the BC Legislature and the CPR shipping terminal on Belleville Street in Victoria, drew up the plans for the telegraph station. The building contained about fifty rooms, including a fine dining room with view windows, and amenities such as a billiard hall, a library with three thousand books and a music room. The west coast of Vancouver Island had never seen the like of this palatial structure. Later, in 1926, the company added a new concrete building below the original building to house new technology and allow the twinning of the undersea cables. The ugly building was nicknamed “Alcatraz” by locals.

The scrappy little settlement of Bamfield was established in 1901 when James Budge McKay built the first house there, a boarding establishment with ten bedrooms, a dining room and a store to accommodate workers building the Cable Station. Some fishermen and their families soon joined him in the protected harbour, not expecting that their pretty, isolated village would soon gain international renown because of the Trans-Pacific Cable.

The village of Bamfield derived its name from William “Eddy” Banfield (so spelled) who came to the area in 1849 as one of the west coast’s earliest traders. In 1859 he established himself as the first white settler in Barkley Sound when he took up land on Rance Island in Bamfield Inlet, having purchased it from the Huu-ay-aht people for “six blankets, some beans and molasses.”73 In 1861 Governor Douglas appointed him government agent and Indian agent for Barkley Sound. Only a year later, Banfield drowned under suspicious circumstances. Over the years the name “Banfield” became “Bamfield” through common usage.

In 1921 Australian Bruce Scott answered an advertisement in the Sydney Morning Herald for “boys fifteen years of age to learn submarine telegraphy and work overseas,” and after being trained as a telegraph operator, and having served at various telegraph stations in the Pacific, in 1930 he found himself posted to the Trans-Pacific Station at Bamfield. He would work there for thirty years and came to love the west coast, writing four books, not just about his working life but about shipwrecks, peoples of the coast and Bamfield itself.

In his book Gentlemen on Imperial Service, Scott explains that as time passed, the station expanded:

"There were also twelve houses and two apartments for married staff; all fully furnished with rugs and carpets, bed-linen and blankets, crockery, cutlery and kitchen utensils—all of which were maintained and replaced when necessary. Accommodation was rent-free and considered to be an isolation bonus. The houses were maintained by a carpenter and outside staff. Laundry and cooking was done by the Chinese laundrymen at a nominal cost...74

Outdoor recreation included tennis on concrete tennis courts, hiking on forest trails, swimming on ocean beaches, salmon fishing, hunting game and ducks, and photography. For indoor recreation there was a dance hall equipped with a stage for amateur theatricals and concerts, and a cinema for movies. Life on the station compared to living at a country club.75

"

The basement at the station provided accommodation for a dozen Chinese men, half of whom would act as servants while the remainder did maintenance work on the property. “You know those poor Chinamen, they were paid slave wages,” recalls Bamfield’s Johnnie Vanden Wouwer. “That’s why they had Chinamen: they were the only ones that would stick it out. But the manager knew better than to boss them. They went at their own speed and that was it. You couldn’t speed them up. But they worked steady, you betcha! They worked eight hour days and in the evening, when their shift was over, they fished cod at the floats there, rock cod.”76

On October 31, 1902, in the first message transmitted on the new All Red Line, the Fijian people sent greetings to King Edward VII in London. “It seemed strange that these islands, so remote, so recently occupied by cannibals, should be the first to transmit, through the newly completed Pacific Cable, a message of respectful homage to the Sovereign of the Great British Empire,” effused Sir Sandford Fleming in an interview after the event. “The fact is significant. Is it not another indication that the civilization of the human family is steadily advancing? In this relation we are reminded that, in the British Islands, in that part of the earth where the Fiji message was received by the King, the inhabitants, now highly civilized, were, a few centuries back, a race of painted savages.”77

The telegraph operators relayed Morse code messages at a rate of 24 words or 120 letters per minute, an easy speed for a capable operator to transmit and to read, and 334,560 words could be moved daily in each direction through the Bamfield station. “Additional space could be saved using abbreviations,” says Bruce Scott. “At Christmas time the text of messages containing “Merry Christmas Happy New Year” was abbreviated to MXHNY which the receiving operator typed up in full, thus increasing the capacity of the cable and the speed at which the operator had to work.”78 With re- transmissions, such as those done at Bamfield, it generally took from ten to fourteen hours for a message to be sent around the globe by the various cable stations along the route.

During the years when the cable station dominated the Bamfield skyline and gave it international prominence, only about two hundred people, other than those working at the telegraph facility, resided there, most of them making their living as fishermen. As well, 129 members of the Huu-ay-aht people lived in their main village of Anacla, about 3 miles (5 km) from Bamfield. Their population had numbered in the thousands prior to the arrival of Europeans, but had been decimated by diseases such as smallpox.

With its sheltered harbour and easy proximity to the fishing grounds of the Pacific, thirty or forty boats, mainly trollers, called Bamfield home, and in the summer months as many as a hundred boats might tie up there.

The Maquinna generally arrived around midday and stopped for up to two and a half hours on her northbound journey, depending on the weather and the number of stops made since leaving Victoria. She off-loaded supplies for the cable station, and all goods were carried up to the station on a rail trolley pulled by a cable wound round a drum and driven by a gasoline engine. Passengers disembarked to take tours of the imperial cable station and its facilities. This provided the young bachelors who worked there the golden opportunity to escort any young women who happened to be tourists aboard the ship. Jan Peterson attests this in her book Journeys: Down the Alberni Canal to Barkley Sound in an interview she did with Bruce Scott. He recalled:

"The coastal steamer called in at Bamfield in the summertime, it was filled with tourists, and the bachelors used to put on their flannels and blazers and go down and eye the human freight, and if possible... well the best way to get to know a person or say, a young lady, was to ask them if they wished to see over the Cable Station. Of course everyone wanted to do that, so you had your foot in to a good start. So you saw them over the Cable Station and saw them on board and said well, when you come back they usually hold a dance in the hall at the Cable Station and I’ll see you then. So the boat came in on its return journey about four days later, came into Bamfield about midnight and stayed until four or five o’clock in the morning and the bachelors entertained the passengers to a dance at their hall. We had our own orchestra, a five-piece orchestra, and it was an affair which was much looked forward to by the passengers and much enjoyed by the bachelors too.79

"

In his own book Bamfield Years, Scott describes how he met his wife at one of these dances. She had come ashore on the “up” trip, and he did not expect the dance on the downward trip to be particularly entertaining, but he went anyway.

"When the ship returned, we were having a small dance in the Cable Station library. We gave no thought to her passengers since it was wartime and the station was under military guard to prevent sabotage. No strangers were allowed beyond the wharf unless accompanied by members of the staff.

Halfway through the dance, Captain “Red” Thompson [who succeeded Gillam as the Maquinna’s master] entered with a tourist on his arm... he introduced me to the young lady, whose name was Pauline. It was a case of interest at first sight. We danced and talked until the ship sailed at three o’clock on the morning. I did not see her again until the following year but we corresponded regularly. The following summer she came to Bamfield for a brief holiday and we hiked, boated, swam, took photographs and found that we had many interests in common.80

"

The two married in 1942, moving to one of two cabins Scott had built in a small bay near Aguilar Point at the western entrance of Bamfield Inlet, and which they set about expanding. Bruce ordered all the lumber for the job from a mill in Port Alberni and he expected the Maquinna to deliver it at around three in the afternoon. But a delay loading cases of salmon at Kildonan meant the ship didn’t arrive until after midnight. Bruce and a friend man oeuvred a borrowed barge alongside the ship:

"By the light of the glaring floodlights, the lumber came at us in sling-loads. The mate knew his job and lowered the heavy timbers first. It was frightening the way the stuff came down, but it was well under control and we were never in danger of being hurt. Being amateurs, it took us a few sling-loads before we got the idea of stowing the lumber properly so that the raft didn’t tip too much. The winches shirred and hissed steam as sling-load after sling-load came down. There seemed to be no end to the amount of lumber. The raft settled deeper and deeper until it was a foot under water and pieces of lumber began to drift away on the tide. I shouted at the mate and asked him how much more there was. “Quite a lot,” he said, so I told him to put the rest on the dock and I would collect it at some future date.81

"

Scott and his friends towed the barge to the bay where the house would be erected and after unloading the materials construction began. The Scotts would live in their refurbished house for many years until they moved to Victoria in the winter months, and later they ran Aguilar House, as they named it, as a bed and breakfast during the summer months. They eventually sold it in 1971.

In 1959, after fifty-nine years of service, the Bamfield Trans-Pacific Station closed, with the relay station moving to Port Alberni.

In mid- to late afternoon on her northbound trip in 1924, with all cargo for Bamfield off-loaded and new passengers welcomed aboard, many of them bound for the next major stop at Port Alberni, the Maquinna backs out from the dock into Trevor Channel. She turns eastward into the Alberni Canal, at 30 miles (50 km) the longest inlet on the west coast. In 1931 this would be renamed Alberni Inlet, “because of fears shipping companies would think it was a man-made canal requiring fees.”82 Next stop will be Kildonan, 14 miles (22.5 km) away in Uchucklesit Inlet. Once the Maquinna turns into Uchucklesit Inlet the passengers, depending on the time of year, begin smelling the rancid, oily stench emitted by the pilchard reduction plant here, the biggest such facility on all of Vancouver Island’s west coast.