Chapter 11: Clayoquot Sound

The next leg of the Princess Maquinna’s northward journey takes her through some 27 nautical miles (50 km) of Clayoquot Sound. This proves to be relatively easy travel because two large islands, Vargas and Flores, and a number of smaller ones, shield the sound from the open Pacific. Clayoquot Sound comprises a labyrinth of inlets and bays, fed by four main rivers, the Bedwell, Moyeha, Megin and Sydney, and many smaller creeks and streams.

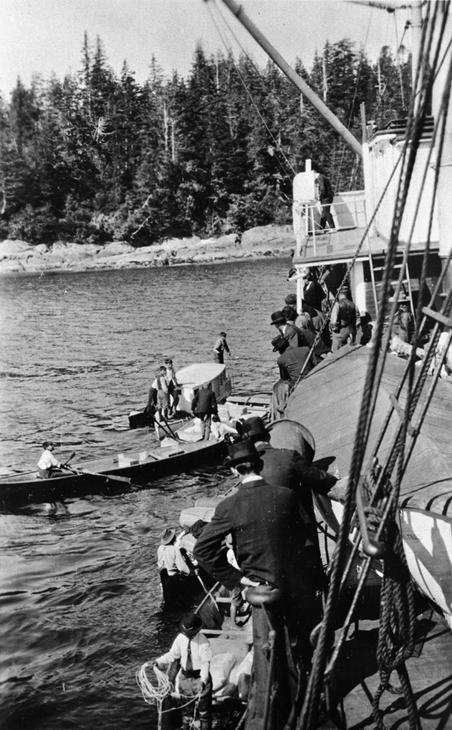

To serve the isolated settlers, fish plants, logging shows and mining enterprises, the Maquinna makes “boat stops” as she travels up the sound. Often a lone occupant in a rowboat, a small gasboat or a canoe comes out from shore to the side of the ship so crew can off-load their mail and goods. “She would often pull into a small float camp or a booming ground and unload loggers’ cargo out the side hatches,” recalls Bill Moore in BC Lumberman. “She had two large iron doors on her sides down near the water’s edge, and when these were opened freight could be passed out to waiting hands. It may be the middle of the night in a snowstorm or it might be in a strong tidal inlet. No matter, the captain of the Maquinna would hold her in position while the logger or fisherman took his freight off.”117

By the 1930s, people who owned radios in the remote camps and communities up and down the west coast could determine the approximate time to venture out in their boats to meet the Maquinna. Vancouver’s Daily Province newspaper owned a radio station, CKCD, and its evening newscaster Earle “Mister Good Evening” Kelly would inform westcoasters of the Maquinna’s progress so they could time meeting the ship for boat stops. In 1929 Kelly, an Australian of Irish heritage who had been wounded at Gallipoli, arrived in Vancouver and for the next seventeen years read a fifteen-minute-long newscast every evening at 9 p.m., seven days a week. Sartorially elegant, Kelly always delivered his Saturday broadcast standing in front of the microphone, as many other announcers at the time did, wearing impeccable evening clothes. He carefully articulated every word. “He spoke so slowly and formally,” remembers Tofino’s Marguerite Robertson. “He always said Clay-oh-quat—never ‘Klakwot’—and Tofino was always To-fee-no and Ucluelet was You-cloo-let.”118 He always concluded his broadcasts with what he referred to as “the benediction”: “‘We wish all our listeners, on land, on the water, in the air, in the woods, in the mines, in the lighthouses—and especially my friends on the Good Ship Maquinna, now off Cape Beale [or departing Tofino, or wherever] a restful evening.’”119 Those pronouncements each night provided westcoasters with a reasonably up-to-date idea of where the Maquinna was on her journey up or down the coast.

About 2.5 nautical miles (4.5 km) up the sound from Clayoquot, the Maquinna makes her next stop, at Kakawis on the west side of Meares Island. Here stands an imposing white building, the Christie Roman Catholic Indian Residential School. Opened in 1900 with just thirteen students, it soon grew to house over one hundred, and would continue operating until 1971. Initially staffed by Benedictine priests and nuns, many of them from Belgium and Switzerland, the school possessed a number of scows and barges, making loading and off-loading somewhat easier than the process at Clo-oose, where canoes were used. However, rough weather could sometimes swamp or overturn these scows. Given the number of students and staff living at the school, sustaining them required large amounts of supplies ranging from building materials to furnishings to food, and the unloading “required careful timing, reasonable tides, and a good deal of assistance. Landing flour was particularly tricky, for once wetted it could not be used—and huge amounts of flour arrived regularly... Deliveries of two tons of flour at a time could arrive at Christie School requiring every available person to swing into action.”120

Though a Protestant and an Orangeman, Captain Gillam befriended the nuns and priests who ran Christie School, becoming a particular friend of Father Charles Moser. Father Charles had been on the west coast since 1901, and in his diary often mentions Captain Gillam. Possibly because of Gillam’s friendship, students travelling to and from the school on the Maquinna sometimes slept in staterooms, despite regulations indicating that such accommodation was for white passengers only. In 1924, when Father Charles shepherded a large group of First Nations children to the school aboard the Maquinna, he recorded in his diary: “I had 29 children to take care of after leaving the Whaling Station [Cachalot], and at 9 p.m. at Nootka got four more. The 33 spent the night divided in eleven staterooms. For fares and rooms I paid the Purser $146.90.”121

On another occasion, on April 24, 1927, he wrote of children heading back to their villages from Christie School: “Said Mass at 4 a.m. When we heard the steamer [Maquinna] whistle, got baggage and children ready... I got staterooms for the girls and placed the boys in the steerage.”122 Steerage usually meant that the children were put out of the way in one of the cargo holds. “Violet George, who lived at Nootka, first travelled to Christie School on Meares Island when she was six years old, with her two older sisters. Her father paid the fare from Nootka Cannery, and the girls travelled in the cargo hold, where they stayed for many hours before reaching the school. With no benches provided, they sat on their suitcases; a bucket served as a toilet.”123

It was the norm for Indigenous travellers to travel outside on the open forward deck in summer or, in winter, in the cargo hold between decks. Though this policy doesn’t appear to have been a published regulation originating from head office, a look at the fare schedules reveals it. A CPR document from 1913 listing meal rates states: “Indian and Oriental Deck Class Tickets do not include meals or bunk, and such passengers may be served Second Class meals at a rate of 25 cents per meal.”124 A 1936 Fare Schedule instructs pursers to charge “North American Indian Deck Class ONEHALF the First Class fare between ports when the First Class fare does not include meals and berth and that, where they do include meals and a berth to First Class passengers, they should charge TWO-THIRDS the First Class fare.”125 So, for instance, if an Indigenous person travelled from Port Renfrew to Port Alberni in 1936, with no need for meals, the cost would be half a First Class fare, or $2.20. A 1939 Fare schedule lists fares as: First, Indian and Deck Classes.126

In summer the forward deck of the Maquinna would be packed with Indigenous people and their possessions as they made their way from their reserves to work at various fish plants, as Bill Moore describes in his article in the BC Lumberman in 1977: “The fishing and cannery industry was going great guns in the 1920s and a great deal of the work was done by native Indians. Early each summer on her way north, the Maquinna would pick up a few hundred native Indians at various stops along the way and deliver them to the canneries at Rivers Inlet on the northern mainland of BC’s coast... these people were herded together on deck and down below, sleeping where they could, and getting their own meals. When the ship was at a dock, they would catch some fish and use their big iron pot to cook the fish—on the beach. The trip took several days to Rivers Inlet and one can only sympathize with the plight of those people.”127 In late summer and early fall Indigenous people also found seasonal work in the hops fields of Puyallup County in Washington State, and whole families boarded the Maquinna for the trip down to Victoria, where they then took other steamers to their US destinations.

Putting Kakawis behind, the Maquinna continues north, then heads west into Calmus Passage, at the north end of Vargas Island, passing Port Gillam on her port side. Named after Captain Gillam when he was captain of the Tees, the wharf built here prior to World War I served a group of homesteaders attempting to establish themselves on the island. After most of the men left Vargas to serve in World War I, the settlement failed, and the Port Gillam wharf vanished in a severe winter storm only a year after it had been built. When the need arose, steamers could still make infrequent boat landings there. On the mainland, across from Port Gillam, lies imposing Catface Mountain, so named because the copper deposits in the rock gives it a catlike appearance. The waters off Catface are shallow and treacherous, as Father Charles Moser relates in his diary for December 7, 1923. While travelling south on the Maquinna: “Off Catface Mountain steamer touched ground two times, no damage except in the dining room where dishes were hurled to the floor and broken.”128

Once away from the choppy shallows off Catface, the ship arrives at the large First Nations village of Ahousaht on Flores Island. Ahousaht stands on the west side of the long, narrow Matilda Inlet, with the Marktosis Reserve on the east side, and is the biggest First Nations settlement in Clayoquot Sound, with a population of approximately 200 in the 1920s.129 A Presbyterian Residential School, established at Ahousaht in 1904, stands only 9 miles (14 km) from the Christie Roman Catholic School at Kakawis, making these the closest residential schools to each other in British Columbia.

Dr. Richard Atleo, Chief Umeek of Ahousaht, recalls the arrival of the Maquinna as it neared Ahousaht:

"When the Princess Maquinna was approaching Ahousaht, when it was still on the other side of Catface Mountain, you could feel it. You could hear it. This was back when there were no sounds from machinery; when a man could go to the top of the hill and call people to a feast in the traditional way. You could feel it in your body: it’s almost imperceptible, but you could feel it. It’s gentle, but it’s also shocking because of the contrast... A huge machine like that, ploughing the waves, disturbs the environment, sets your heart a-pumping... because it was so quiet normally. It was very dramatic. This would only be true in the summertime, though; in wintertime the waves would be roaring loudly.130

"

Inspector H. Brodie describes what he witnessed on his trip to Ahousaht in 1918, before a dock had been built in the 1920s. “This is a very beautiful spot, the village being on a curved beach. The majority of our Indians disembarked at this point. It is very interesting disembarking them, as they are all handled in dugouts. The Indians pile into the dugouts, baggage, men, women, children, dogs, pots, pans, etc. etc. Among other things there were small cook stoves, stove pipe, hats, strips of oil cloth and all sorts of paraphernalia. It took about an hour to disembark all the Indians.”131

By 1921, Ahousaht had become home to the legendary, larger-than-life Gibson family: father William, mother Julia and sons Clarke, Jack, Earson and Gordon. William had been active on the west coast for years before then, harvesting lumber for various markets and encouraging settlement. He built his own sawmill at Ahousaht in 1921, cutting spruce for airplane frames and splitting cedar shakes and shingles. The Gibsons relied on the Maquinna to carry their products to market, but with only a small dock unable to accommodate the ship they had to improvise, and in Gibson-like, make-do fashion they did just that, as Gordon describes in his book Bull of the Woods:

"The Maquinna couldn’t tie up close to our dock so we would load our shingles on a huge float 50 feet by 140 feet... then we would tow it out to be anchored about a mile down the bay. We would load the shingles from the float onto the ’tween decks of the Maquinna, a good 5 feet up from the water line.

"

This would take four or five hours, usually at night, by which time we were soaking wet from the rain the salt water or sweat. My father and brothers would make our way home, have a hot meal and fall into bed for a few hours’ sleep before starting to operate the mill in the morning. After a few months of towing the float out to the Maquinna we decided to secure the raft to the shore, and take a chance that Captain Gillam could bring the Maquinna in to us.

We drove in some piles and I reinforced the lashing, putting in stiff-legs—poles about 80 feet long—to keep the float offshore. We used cables that were brought down from an old mine which had started before World War I at the head of Bear River. Fastening 1,000 feet of this cable firmly to the float at each corner, we secured it to stumps on shore. Now as we cut our shingles we were able to pile them on our float ready for shipment eliminating that terrible towing trip. Because the engine in our boat had less than 10 horsepower we had to go down the bay with the tide and sometimes wait for six hours for another tide to make the return trip. Captain Gillam came in to look at our mooring and decided that he would risk bringing the Maquinna alongside it. She tied up to this float six times a month for many years, docking three times going north and three more times on her return trip.132

In the mid-1920s when the enormous schools of pilchards arrived annually on the coast, sometimes stretching the equivalent of two or three acres under the water, the Gibsons saw an opportunity. They used their pile driver to build foundations and wharves for reduction plants up and down the coast. They also sold lumber from their sawmill to build the reduction plants. In 1926, after seeing the profits being made from the reduction plants they helped to build, they decided to construct their own plant at Ahousaht. That kept them even busier, and financially better off. “We logged and ran our mill in the winter, as well as shipping salt salmon to China, and we went fishing pilchards in summer,”133 writes Gordon in Bull of the Woods.

Amid all this enterprise the young, socially isolated Gibson brothers took full advantage of the opportunity to meet the young lady tourists travelling on the Maquinna. “In the summertime the Maquinna would bring a group of tourists up the coast, arriving at our place about six in the afternoon. All of us young bucks were tickled to death to take the tourists for a walk to the outside beaches, often building a campfire for a singsong and perhaps stopping for a soak in the hot springs on the way back. Naturally, we were most anxious to escort any of the attractive young ladies. After the walk we took everyone back to our home for coffee and a dance.”134

In 1933 the pilchards that had been on the west coast for fifteen years almost disappeared. The Gibsons, like many other reduction-plant owners, experienced a severe economic downturn, nearly bankrupting them. It took them a number of years to recover from this financial crisis, but they weathered the storm by taking every opportunity to make money. In 1932 the Maquinna needed a new mast and the Gibson brothers were renowned for finding any way to make a buck, so with the CPR offering $100 to procure one, the Gibsons jumped at the opportunity. “That was a huge sum of money for us and we immediately contracted to do the job,” writes Gordon. “I knew where such a tree was standing on one of our claims: an enormous spruce tree straight, tall and perfectly symmetrical. Jack and I felled it onto smaller skid trees so that it would slide into the water under its own momentum. The tree was 24 inches round at the base and 16 inches at the 100 foot mark. It was the perfect specimen of the type of spar Captain Cook noted from the bridge of his ship on his first trip into Nootka. He was looking for trees that would be suitable for masts for the British Navy.”135

With business concluded at Ahousaht, Captain Gillam signals to the engine room to reverse engines. The Maquinna slowly backs out of Matilda Inlet, edging carefully toward wider waters. Al Bloom explains the tricky manoeuvres:

"The inlet leading to Ahousaht was so narrow that the ship had to travel in reverse for half a mile or so on the way out, before there was enough room to turn around. I made the trip one night when it was so dark and foggy that I couldn’t see either shore, but the Maquinna managed to be right on course and found that little dock, just by giving periodic blasts on the whistle and listening to the echoes. And then she retraced the route in reverse! The crews were fantastic seamen. Someone asked one of the captains how he could remember where all the rocks were and he replied, “I can’t. I just know where they aren’t.”136

"

Once out of Matilda Inlet, the first part of the journey north up Millar Channel proves fairly straightforward until it narrows considerably at the north end, through the tight Hayden Passage between Flores and Obstruction Islands. Here the tide sometimes runs at 3 to 5 knots, depending which way the current flows, but once through, Gillam changes course, heading west down Shelter Inlet and then turning northwest into Sydney Inlet. The Maquinna’s destination is up Stewardson Inlet, which branches westward about halfway up Sydney Inlet. Once Captain Gillam turns the ship into Stewardson Inlet he proceeds halfway up until he reaches the Indian Chief Copper Mine, Clayoquot Sound’s most successful mining operation.

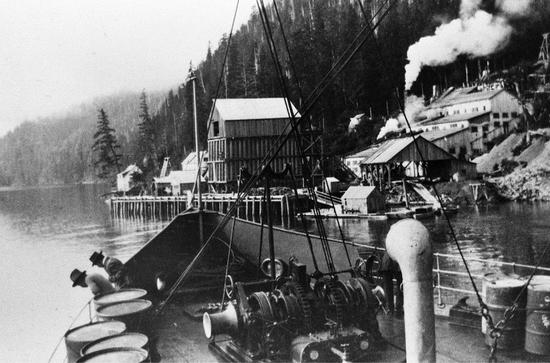

Mining—or the dream of mining—fired the imagination of countless prospectors in Clayoquot Sound, some of them arriving in the area as early as the 1860s. Victoria newspapers referred to the sound as “the mineral belt of the Island.”137 A number of gold rushes in the area led to high hopes and bitter disappointment for many. However, the Indian Chief Copper Mine in Stewardson Inlet led to employment for many, and greatly increased cargo loads for the CPR steamships. With the mine entrance halfway up the side of the inlet’s steep cliffs, an aerial tramway brought the ore down to a dock built on the shore, while a small sawmill kept itself busy cutting lumber for pit props and shoring. A concentrator, added during World War I when copper prices soared, helped the mine produce 300 tons of ore a day, all of which had to be transported by CPR steamers to Tacoma, Washington, for smelting.

As the Maquinna’s journey continues, the passengers, now familiar with the ship and its routine, fill in their time viewing the scenery, watching the loading and unloading of cargo and passengers, playing games on the upper deck—weather permitting—conversing with fellow travellers in the lounge, chatting to crew members, or napping in their cabins, all the while keeping an alert ear for the breakfast, lunch or dinner gong that calls them to the dining room for yet another superb CPR repast.