Chapter 15: Quatsino Sound

Brooks Peninsula sticks out the side of Vancouver Island’s west coast like a large fist. If passengers have avoided sea-sickness so far, they’ll certainly be challenged here. Should they still be upright, they will see one of the finest sights of the entire voyage, Solander Island, named after the naturalist aboard Captain Cook’s first voyage. Standing just under a mile (1.5 km) off the coast it rises high out of the sea and resembles Cathedral Peak in the Canadian Rockies, with heavy seas breaking over the rocks in clouds of spray. On two of its sloping sides, hundreds of sea lions lounge, barking and belching, as well as thousands of screeching seabirds, creating a cacophony of sound. When Captain Gillam sounds the ship’s whistle, the sea lions flop down the sides of the rocks and into the sea, making a great hubbub.

Once the Maquinna rounds Cape Cook, at the northwestern tip of Brooks Peninsula, and crosses Brooks Bay, Captain Gillam and his helmsman keep an eye out for the Kains Island Lighthouse at the western entrance of Forward Inlet, branching north from Quatsino Sound. At night, the light helps guide vessels into Winter Harbour, the next port of call. Built with great difficulty in 1908, the Kains Island Lighthouse, 5.5 nautical miles (10 km) out from Winter Harbour, represents one of the loneliest postings for any lightkeeper on the west coast. In 1918 the Daily Colonist reported the effort of James Sadler, the lightkeeper, to help his wife Catherine, who “has become violently insane from the awful loneliness of the west coast and two of her four children were in a precarious state through lack of food. Sadler was found at his post... after he had exhausted himself in his efforts to keep his wife from committing suicide.”167

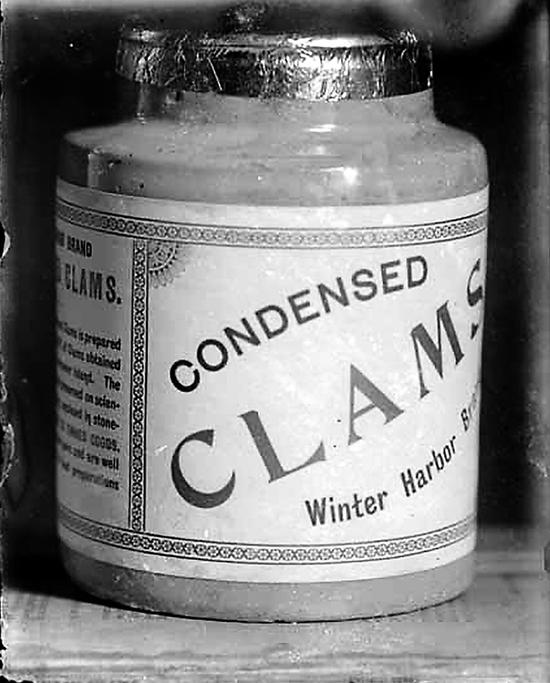

Once past the light, the Maquinna steams north into Forward Inlet and into Winter Harbour, so named because it provided a safe haven for sailing vessels during winter storms. It is the most westerly settlement on Vancouver Island. Kwakiutl villagers and a few fishermen and loggers live here. Jobe (Joseph) Leeson, originally from Coventry, England, arrived here in 1894 with his family, and he established a trading post, J.L. Leeson & Sons Trading, serving the local Kwakiutl people and visiting whaling and sealing ships. In 1904 Leeson established the Winter Harbour Canning Company, canning clams and crabs and employing up to forty Chinese and First Nations workers. Credited with inventing condensed clams, he and his sons also sold salted fish, and made wooden barrels.

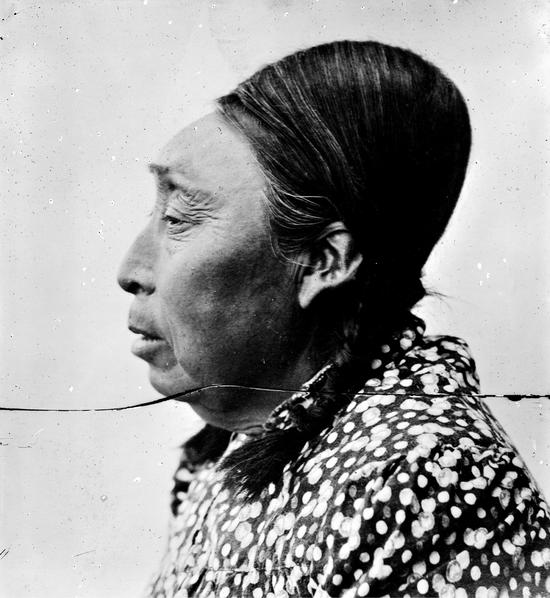

Early in his life, Leeson’s son Ben acquired an interest in photography, and over the years took hundreds of photographs of life in Winter Harbour and the Quatsino Sound area, with a special interest in the “flat-heads” of the Kwakiutl women. Local custom dictated that the heads of little girls be bound, with boards tied around their foreheads, leaving them with flat heads for the rest of their lives. Leeson experimented with his art, often merging and combining images in order to create special effects, and hand-colouring many of his photographs. Peter Grant relates in his book Wish You Were Here: Life on Vancouver Island in Historical Photographs, that Leeson’s daughter, Anne, “would go down to meet the Princess Maquinna on her thrice-monthly visit to Winter Harbour and sell her father’s postcards and pictures to tourists.”168

Later, in 1937, Albert Moore established a logging float camp in Winter Harbour; it was taken over in the 1950s by his son Bill, who renamed it W.D. Logging. He painted his logging machinery a distinctive “salmon pink” colour. A well-read man who loved jazz, Moore wrote many articles in the BC Lumberman about life and logging on the west coast and coined the delightful term “Saltwater Main Street,” referring to the BC coastal shipping routes of the CPR and Union Steamship vessels in the days before roads and airplanes. Bill’s son Patrick, born here in 1947, became the co-founder and president of Greenpeace, spearheading protests against nuclear testing, whaling and seal-pup hunting in the 1970s and 1980s.

In one of his many articles, Bill recounts an incident following the logging camp’s three-week Christmas closure, one January in the early 1940s. He and his boom man had stayed in camp, and he was due to meet the Maquinna, which was bringing in the twenty-five-man logging crew returning after the break:

"By then our inlet had a small floating dock with a galvanized tin shed on it to store supplies out of the weather. There was no walkway to shore, so our dock sat out in sort of mid-channel, anchored to the bottom.

The “Good Ship” was due in at 4 a.m. (yes, it was snowing) and it was my job to meet her and take the crew and supplies farther up the inlet to the float camp. Fred, the boom man, was to have the bunkhouse wood fires going and to have lit the cookhouse wood range.

“Kelly” [Earle Kelly’s radio program on CKCD radio] told me the night before when the ship would be in, so I slept aboard our gas boat ready to go out to the dock when she arrived. However, being young and heavy of sleep, I did not awaken as I should have and it was long after the “Good Ship” had departed that I was yelled at by a passing fisherman and told—“Ya got a whole passel of cranky loggers out there on the dock, kid.”

I started up the engine and with a small searchlight on proceeded to the dock in the heavy snow. I shall never forget the sight of those 25 snow covered loggers—standing like penguins on the dock as my searchlight shone on them. Angry? No, they were way beyond that! The tin freight shed was full so there was no place to take cover. I had towed a large red cannery skiff behind my boat to load freight into. Twenty five cold loggers jumped at the freight to load it in the scow and about seven a.m. we headed up for the camp. To make the morning near perfect, Fred, the boom man had overslept and forgotten to light the fires. A couple of the loggers who would speak to me told me that their three day journey from Port Alberni had been one of the roughest on record for the “Good Ship”—Oh boy!169

"

Pulling out of Winter Harbour, the Maquinna heads east through the tranquil waters of Quatsino Sound, a body of water so big it almost cuts off the top end of Vancouver Island, extending to within 7 miles (11 km) of the east coast of the Island. Soon the vessel arrives at the village of Quatsino. In 1894, thirty or so Norwegian farmers and their families arrived from North Dakota to take up eighty-acre land grants offered by the Canadian government. The settlement features a one-room schoolhouse, St. Olaf’s church (built in 1897) and the Quatsino Hotel, which opened in 1912. In an article published in The Islander in 1980, writer I.M. Ildstad described how Captain Gillam often took the small liberty of leaving the ship for a brief period while in Quatsino.

"While the Princess Maquinna was docked at the wharf the captain would frequently turn the unloading of freight over to his first officer and then walk about two miles [3 km] along a well-worn trail connecting the homes of the settlers to our own home. Here he and my father, Thomas, would have lively discussions on events of the time. These discussions were most enjoyable for my mother served them excellent coffee, home-made cake, and in season fresh strawberries and cream.170

"

“Captain Gillam was a popular man on the coast,” adds Bill Moore, proceeding to describe a memorable event.

"My friend, Frank Hole, remembers his days in the Quatsino school when, once a year, the captain would send word up to the teacher that he was ready to take the school children on board for a day’s cruise of Quatsino Sound. Of course the great CPR service was theirs—from ice cream to white linen tablecloths and lovely silverware. Frank says it was the big day of the year.171

"

The Maquinna continues eastward, passing Ohlsen Point before turning into Quatsino Narrows. Once through into Holberg Inlet, she heads northeast to Coal Harbour on the east side of the inlet. Named after an unsuccessful mine founded here in 1883, Coal Harbour would later house a seaplane base during World War II. The float planes from Coal Harbour patrolled the Pacific searching for Japanese submarines and invasion fleets. After the base closed in 1945, the enterprising Gibson brothers, always on the lookout for any money-making opportunity, took over the base in 1948 and ran it as the last whaling station on the coast until they closed it in 1967.

In August 1907 this remote village gained notoriety when a syndicated story, first appearing in the Victoria Times Colonist, ran in newspapers across North America, including the New York Times. It asserted that John Sharp, the caretaker of the mining enterprise at Coal Harbour, was none other than William Quantrill, the leader of the notorious Confederate guerilla group “Quantrill’s Raiders.” This renegade band included the notorious Dick Yeager, “Bloody Bill” Anderson, Jesse and Frank James, and the Younger brothers, and terrorized communities in Kansas and Missouri during the American Civil War. One notorious raid on Lawrence, Kansas, saw the gang massacre more than 150 people.

Toward the end of the war, after Union forces cut up his gang near Louisville, Kentucky, Quantrill was thought to have been killed. But according to the syndicated article, Quantrill survived a bullet and a bayonet stab and fled to South America, later making his way to northern Vancouver Island where he changed his name, logged, trapped and eventually became caretaker at the Coal Harbour mine facility. When in his cups, which occurred often, Sharp told his fellow drinkers that he was Quantrill, but not everyone believed him. However, in 1907 timber cruiser J.E. Duffy, who had been a Union cavalryman during the Civil War, came upon Sharp at Coal Harbour and identified him as Quantrill, an assertion Sharp did not deny.

The story goes that following the publication of the newspaper story, two men with American accents boarded the Tees in Victoria and arrived at Coal Harbour. Next day, Quatsino’s Thomas Ildstad found Sharp suffering from the effects of a serious beating, but Sharp would not identify his assailants. He died the following day. The coroner who examined the body reportedly found evidence of many old wounds from bullets, swords and bayonets. The locals buried him in Coal Harbour. Later, during the building of the seaplane base during World War II, construction work obliterated the grave, and his true identity remains unresolved.

Travelling northwest along the length of Holberg Inlet, the Maquinna finally reaches the village of Holberg, the most northerly stop on her voyage, after sailing some 415 nautical miles (765 km) from Victoria. Danish settlers, who arrived here in 1895, named the village after Baron Ludvig Holberg, a noted Danish historian and dramatist. Some years later other hardy Scandinavians set off from Holberg, hiking to their ill-fated settlement at Cape Scott on the northwestern tip of Vancouver Island. The trek took them to San Josef Bay on the outer coast, where they followed a rugged trail to their settlement. Promises from the provincial government to build a wagon road to the settlement never materialized, but for years the settlers struggled to establish productive farms and gardens there, hoping to ship their produce to Victoria. Like so many other hopeful ventures on the west coast, the Cape Scott settlement eventually petered out.

On this voyage up the west coast, passengers have visited one remarkable garden—George Fraser’s at Ucluelet. They have also heard about Cougar Annie’s at Hesquiaht. Now here, about 9 miles (14.5 km) west of Holberg, lies another garden, created by Bernt Ronning. Born in Norway, Ronning came to Canada in 1910 and in 1914 began homesteading 160 acres of land midway along the trail between Holberg and San Josef Bay. He built a house, trapped in winter, worked in summer at the Rivers Inlet salmon canneries and, as an expert chef, often served as cook in logging camps. His main interest, though, lay in buying seeds and shrubs from catalogues and planting them in the five-acre garden he had carved from the bush. In turn, he sold seeds and shrubs to others far and wide, all transported out on the Princess Maquinna and other CPR ships.

Two enormous monkey puzzle trees from Chile stood at the entrance to his garden, one eventually growing to over 80 ft (25 m) tall. Inside, peonies from China, rhododendrons and azaleas from India, yew and rowan trees from Ireland, heathers from Scotland, flowering cherries as well as oriental maples from the mountains of Japan, and many other species flourished in his garden. In 1951, Cecil Maiden noted how these species were all “thriving in the warm, moist air of his tropical valley, where winds are barred an entrance most of the year, and the soil is deep and inviting.”172

No hermit, Ronning owned a pump organ and a gramophone and often hosted gatherings at his house where local folks enjoyed his fine refreshments and danced until first light. As dawn broke, the partygoers picked up their sleeping children spread round the house and walked back to their farms to feed, water and milk their cows.

Ronning maintained that the “best garden is the one outside my garden. There is nowhere else as bright with the wild flowers as these hillsides in spring.”173 He died in 1963. A small group of dedicated volunteers still tend his garden.

Business completed at Holberg, the Maquinna heads southeast down Holberg Inlet, through Quatsino Narrows, then steams some 7.5 nautical miles (14 km) southeast down Neroutsos Inlet, named after Captain Cyril D. Neroutsos, who succeeded Troup as superintendant of the CPR’s shipping arm. About halfway down, on the west side of the inlet, the ship stops at Yreka, a copper mine boasting a store, blacksmith shop, sawmill, post office and bunkhouse/dining hall accommodating the sixty men who work there. As she nears the bottom end of the inlet, the Maquinna makes another stop, at Jeune Landing on the eastern shore, near where another copper mine operates, at one time employing thirty-five men. After a quick stop, the ship proceeds to the nearby company town of Port Alice, the biggest settlement in Quatsino Sound and the Maquinna’s final stop before beginning the return journey to Victoria.

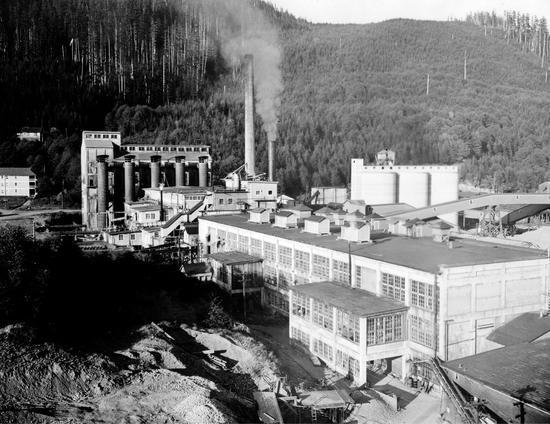

Starting in 1917, the four Whalen brothers from Port Arthur, Ontario, founded the town to service the pulp mill they established there. Occupying sixty acres, the town had fifty homes, a hotel, a store, rooming houses and a sawmill—which it was claimed had the longest roof in the British Empire. The Whalens named the town after their mother, Alice. A good deal of the material used in building the town arrived aboard the Maquinna.

The town’s 1,500 residents lived right next to the pulp mill’s belching smokestacks and toxic outfall, which contributed to the degradation of the nearby water. Even the steamer contributed to the pollution, as long-time resident Eve Smith attested: “The Maquinna, having no refrigeration, brought live cattle to Port Alice to provide meat for the town and once they arrived they were slaughtered on the ‘Oil Wharf,’ with hay at one end and slaughter at the other, and the offal going into the chuck [the sea].”174

One of Captain Gillam’s daughters, Irmgard—he had three daughters and a son—married Angus MacMaster in 1927 and they became residents of Port Alice in 1929. For two years, Captain Gillam made a number of visits to the MacMaster home when on the Maquinna’s regular runs, before his untimely death in May 1929.

John Steinbeck’s friend Ed Ricketts, the famous botanist and ecologist, travelled on the Maquinna from Clayoquot to Port Alice in 1947, with his wife Toni. He left with a low opinion of the place. “Being a Saturday night, there was a dance and a social ashore. On the Maquinna ladies were prettying themselves for a night on the town.” The merrymaking, however, fell far short of Ricketts’s expectations: “sad, sad dance, not at all like the peppy and drunken country dances at Tofino,” he complained. “These aren’t, however, wilderness people, or fishermen or farmers. They’re townspeople brought up here for a contract; they hate it and maybe they don’t even try very hard to have fun.”175

While the passengers partied, work on the ship continued, with the Maquinna’s winch operator, Shorty Wright, working overtime when the ship stopped in Port Alice, loading bale after bale of pulp into her holds for shipment to Victoria. On her return southward journey, the Maquinna will stop again at many of the places she visited on her way north, filling her hold with all sorts of cargo for shipment and trans-shipment out of Victoria.

As gravel roads began linking Port Hardy, on the eastern side of the Island, to Holberg, Winter Harbour and Coal Harbour, and eventually a road connected Port Alice to Port McNeill in 1941, the Maquinna stopped making calls in Quatsino Sound. She also stopped making intermittent trips around Cape Scott at the top of the Island to Port Hardy and the east side of the Island. She sometimes carried First Nations people from the west side of Vancouver Island to Rivers Inlet on the mainland, for them to work in the canneries there. Over time, roads allowed the residents of these remote northern communities to travel east to Port Hardy and other ports on the east side of the Island. Once there, they could link with the Union Steamships vessels out of Vancouver on the “Saltwater Main Street” that served all the small communities between Vancouver and Prince Rupert. Those steamships made for a quicker journey to the “big smoke” and the bright city lights of Vancouver. However, losing the stops in Quatsino Sound proved to be the writing on the wall for the eventual demise of the CPR’s West Coast service.