Chapter 14: Zeballos and Esperanza

In 1791, Captain Alejandro Malaspina of the Spanish navy sailed to the northern end of what would become Zeballos Inlet. He named it in honour of a lieutenant on his ship, Ciriaco Cevallos. Few outsiders visited the area until 1924, when some prospectors found significant traces of gold there and registered the Eldorado claim.

During the economic downturn of the 1930s other desperate gold seekers came to the area. “A new breed of prospectors arrived on the scene,” writes Walter Guppy, the Tofino author and authority on early mining on the west coast. “These were the fugitives from the hopelessness of the soup kitchens and relief camps... Some were fishermen who had gone broke when the markets for fish collapsed... In 1936 one of these bushwhackers, named Alfred Bird, found a vein that gave spectacular assays in gold.”152

Once the word got out, hundreds of hopeful gold seekers arrived and a small village quickly grew: this became Zeballos. “In 1936 the Maquinna began to make it a regular stop on its coastal journey. It would be loaded stem to stern with freight, and besides the regular west coast passengers, she would carry another load of men and women mad for gold. Prominent engineers from all over the world, promoters, prospectors, clerks, men from every walk of life journeyed to Zeballos,” writes an author with the nom de plume “Old Timer” in a West Coast Advocate article from 1955. “Nearly every cabin [on the Maquinna] has its quota of liquor, and sometimes more. There was a continual whoop de do from the time the schooner left Victoria until she reached Zeballos, where there was neither wharf nor road.”153

Old Timer goes on to describe how the Maquinna anchored offshore, and how all freight had to be carried ashore in small boats, while passengers often piggy-backed over the tidal flats to dry land.

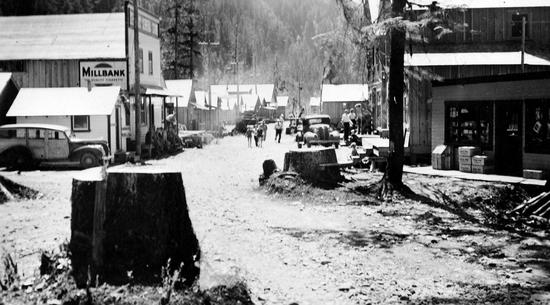

Among the thirty or so active claims being worked near Zeballos, the one named Privateer developed into the chief mine, producing about half of the gold that came out of the area. The little village thrived, becoming a bustling community of 1,500 people and boasting four beer parlours, a liquor store and a bawdy house. Its main wooden-planked street sported false-fronted buildings like a town in a Western movie.

In 1937 Hugh Skinner served as the freight manager in Zeballos and also owned the local store with partners Gene Llewellyn and Roy Seton. Two decades later Skinner recounted in a Daily Colonistarticle the heart-warming events of Christmas Eve that year. He tells how the west coast had been experiencing severe gales, which local mariners were calling “the worst in living memory.” The storms and an accident prevented the Maquinna from calling at Zeballos for ten days because she had suffered “buckled plates caused in a slight brush with a rock and had to be towed to Victoria for repairs.”154

During those ten days the small town almost entirely ran out of essential supplies, and the small hospital ran dangerously low on medicine; one patient died for lack of a sul pha drug and others, including two small children, were in dire straits. “It looked like the bleakest kind of holiday for all concerned and especially of the some 40 or 50 children who had looked forward with great anticipation to the concert and party that had been planned for months,”155 writes Skinner.

Food, medicine, gasoline, kerosene and booze—everything the town required—depended on the arrival of the Maquinna, and everyone in the village waited in anticipation. The hours dragged by as people kept looking down the inlet for the supply ship scheduled to arrive at noon, and now long overdue. “Then suddenly it came, the full throated roar of the Maquinna’s great steam whistle... We rushed to the window, threw our arms round one another and danced a jig. My God what a beautiful sight! There she was just sifting between Twin Islets, dead slow and getting ready to drop anchor, after which the tarps would come off the hatches and she would be ready to disgorge her precious cargo.”156

Skinner and his partners threw on their coats, mufflers, toques and rubber wear and towed their barge through the wind and sleet to the side of the Maquinna.

"“Okay Captain,” I shouted. “Let’s have the medical supplies and the booze first and we’ll take those ashore in the power skiff, then we’ll load the rest onto the scow.” The scene in the bay had an aura of unreality. Floodlights piercing the slanting rain, the hissing steam winches groaning as they deposited load after load on the deck of the huge scow. There were sides of beef, crates of turkeys, fresh vegetables, mountain of assorted canned goods, flour, bacon, drums of gasoline and kerosene. It was now 4:30 p.m. and the children’s Christmas concert was set for eight o’clock and we were only half loaded, however, by six it was all loaded and what a beautiful sight it was. Great mounds of goodies with tantalizing labels on boxes, over there, Ocean Spray cranberry sauce, and look there, Crosse and Blackwell plum pudding were the ones that seemed to jump at me as I steered my precious cargo to the shore.157

"

When the scow slid onto the clamshell beach Skinner realized he faced a problem—there was no one to help him unload, since most of the town’s menfolk had already hit the local bars, and were joyfully tucking into the stock of Christmas booze that had arrived earlier. So he went into the bars where “whiskey flowed like water and loud conversation and raucous singing were the order of the day.”

Calling for quiet he announced: “You all know there are 200 tons of supplies for you out there on my scow and you are not going to get it this night unless you and me make a deal. You all know that in one hour’s time the Christmas Party for the children starts at the school. Well, here’s the deal, you help me get the presents and food to the kid’s party, and help get the supplies to the store and maybe we can then all share Christmas in a meaningful way.”158

Soon forty or fifty half-drunken men lurched out of the bars and began unloading the scow onto a couple of trucks so that by eight o’clock the vehicles bearing the toys, food, crackerjacks and Japanese oranges were chugging up to the school. The men carried box after box into the classroom where parents, children and teacher welcomed them. “Merriment reigned supreme as children screamed with unbridled joy as each man deposited his burden on the makeshift stage. ‘Merry Christmas’ they shouted and the air was full of good will and warm feelings.”159

The men then headed back out into the storm and rain to carry load after load of goods to the store, which then opened for business at midnight and would not shut until 4 a.m.

"Sides of beef were attacked with gusto. Gene was hacking one up with a double bitted axe as he shouted: “Its four bits [50 cents] a pound no matter whether it comes off the head or the tail.” Crates of turkeys were opened and emptied. The women found several bolts of cloth and were busy pawing and clucking over their find as many had not seen any of this for months. Everywhere business was brisk, shoes, shirts, trousers, socks, lamps, hardware, cases of fruit. The fresh vegetables were gone in an instant. There was an unrestrained orgy of buying and this happening at 2 a.m. Christmas morning. People were leaving with carts, wheelbarrows, back packs, all loaded with sustenance. All through the buying spree there prevailed an air of good fellowship and the night was not marred by a single untoward incident. Later, as I was blissfully slipping off to dreamland I swear I heard a voice say from on high: “A Merry Christmas to all and to all a good night,” and the wind howled and all the town slept in peace.160

"

When Edward Gillam captained the Maquinna, throughout the 1910s and 1920s, every year he enacted the part of Santa Claus for children in remote coastal communities, cramming the wheelhouse and even his own sleeping quarters with parcels, to the point that he had nowhere to lie down at night.

In the decade or so the Zeballos mines were in operation, gold worth about $10 million (in contemporary values) left Zeballos on the Princess Maquinna—today, the same gold would be worth some $575 million. The story goes that occasionally the Zeballos postmaster slept with a rifle under his pillow because of the $100,000 in gold bricks he had under his bed as he waited for “Old Faithful” to arrive. The Maquinna carried the gold bars to Victoria, from where they would eventually be shipped to the Royal Canadian Mint in Ottawa.

With business completed in Zeballos, the Maquinna would head back down Zeballos Inlet and then turn west, travelling 14 nautical miles (26 km) down Esperanza Inlet and back into the open Pacific, where she would head north for 15.5 nautical miles (29 km), aiming for Kyuquot Sound on what could be one of the roughest legs of her journey. On our imagined trip in 1924, the ship would not have visited Zeballos at all—the rousing adventures of that community lay at least a decade in the future. But no matter what the time period, the open seas at the end of Esperanza Inlet remain the same.

One of the reasons for this stretch of coast between Esperanza Inlet and Kyuquot Sound being so difficult, says David Young, former captain of the MVUchuck III, who ran this route regularly in the 1980s and 1990s, is:

"The near shore route that we followed between the Sounds is only ten to twelve fathoms [60–72 ft/18–22 m] deep, making storm seas shorter and steeper, more than is the case far out to sea. On one trip it took me five hours to go from Kyuquot to Esperanza Inlet, normally a one-hour run. We had started out in a rising gale that gave us a royal beating even after we moved ten [nautical] miles [18.5 km] offshore to try and find easier traveling. Apart from the wild ride, the difficult bit was turning to enter Esperanza Inlet, which left us beam-on to the wind and sea and our helmsman was barely able to control our direction of travel. Even with full power applied he had to keep the helm nearly hard-to-port to steer the course that was needed.161

"

Given the fair weather on our summer trip in 1924, the Maquinna requires a mere hour of steaming before she rounds Rugged Point at the entrance to Kyuquot Sound, and cruises past Union and Whiteley Islands on her port side. She then steers south into Cachalot Inlet, where the stench forewarns passengers that they are arriving at the Cachalot whaling station. Established in 1907 by Captains Sprott Balcon and William Grant, the plant and its whalers caught and processed an average of four hundred whales a year, shipping the oil to Proctor and Gamble in Cincinnati, Ohio, to make soap. The bones were ground and shipped to California to become fertilizer. During World War I the plant canned 60,000 cases of whale meat for human consumption; reportedly it tasted like salty beef. Inspector W.H. Brodie describes Cachalot whaling station as he saw it on his trip on the Maquinna in 1918:

"The population of the whaling station consists of about 20 whites and 30 or more Indians. It is operated by the Victoria Whaling Co. They are canning the whale meat this year, and have a capacity of 2000 cases a day... Unfortunately, there were no whales at the station, but they were busy cutting up some of the heads, and the canning industry was working at full speed, as was the rendering plant and the fertilizer plant. Everything in connection with the whale is utilized. There is no waste. Two of the steel whaling boats were in the harbour and two others were at sea. They catch the whales between 30 and 40 miles [50 to 65 km] from the station. When caught they are immediately blown up with air, and when a sufficient number are taken are towed to the station. They have had as many as 13 at the station in a single day... Mr. Ruck, the General Manager, travelled North with us, and gave us some interesting information in regard to the station. He also presented us with some very fine whales’ teeth and some whales’ ear drums. They obtain about $2,000.00 worth of revenue from each whale, and have made as high as $5,000.00 from a sperm whale. From a sperm whale they have got as high as 80 barrels of oil. They generally extract as much as 35 to 40 barrels of oil from the ordinary whales. We cast off at 4:40 PM, and had a splendid trip, with fairly good sun, through the small islands to Kyuquot Village.162

"

In the 1940s and 1950s, before heading back out into the Pacific again, the Maquinna would sail north across Kyuquot Sound to Chamiss Bay, where the Gibson brothers ran a logging camp. Such a trip is not on the agenda in 1924, perhaps just as well, for it is unlikely Captain Gillam could go anywhere near Chamiss Bay without being assailed by rueful memories, which go back to the days when he skippered the SS Tees, before he became master of the Maquinna.

On Sunday November 26, 1911, while captaining the SS Tees, Gillam was making his way down from Holberg, at the north end of the Island, to Victoria. When he reached Kyuquot Sound he turned eastward to make a call in Easy Inlet, on the north side of the sound about 10 nautical miles (18.5 km) from its entrance. There he picked up 150 tons of pottery clay at the Easy Creek pits. When backing away from the dock, however, the Tees struck a submerged rock, stripping off her propeller and damaging her rudder. Gillam immediately anchored the ship, ordering his radio operator to begin sending out SOS messages. Because of the Tees’s location amid the sheer rocky walls of the inlet and surrounding mountains, no one heard or acknowledged his signals. This meant that the ship, its twenty-one-man crew and its thirty-eight passengers were, to all intents and purposes, isolated and lost. Not hearing any regular radio messages from the ship, speculation soon arose in Victoria that the vessel had sunk.

Gillam, fearing that his repeated radio messages had not been received, sent one of the ship’s open boats to row to Estevan Point Lighthouse, some 55 nautical miles (100 km) to the south. The lighthouse possessed the only radio transmitter in the area, and it would be able to send a message of the mishap to CPR headquarters in Victoria. Increasingly bad weather, however, forced the lifeboat crew to return to the ship after two horrendous days fighting the elements. “With seas lifting over us, drenched, hungry and cold, we ran in under Rugged Point, and found an abandoned Indian shack, and camped there.”163

Those remaining on the Tees settled in for the long haul. Chief Steward Aspdin takes up the story:

"When we anchored in Easy Creek I lost no time arranging to make the passengers comfortable. We fortunately had some good musical talent, so we arranged concerts, mock trials, etc, and spent as comfortable a time as possible under the circumstances. One had a piccolo and with his solos, some songs and other entertainment, we passed the time... It was decided to make the provisions spin out by serving only two meals/day. On the 3rd day a ship’s boat rowed to Kyuquot village where a bullock was slaughtered and the meat brought back in the boat.164

"

Unknown to Gillam and the people on the Tees, one of their radio messages had been picked up, and rescue vessels set off from various parts of the coast, in a howling winter gale, for Kyuquot Sound to search for the ship.

Eventually, on Saturday morning, December 2, rescue vessels reached the Tees, and were relieved to find all well. The Daily Colonist wrote:

"The complement on board suffered nothing more than the missing of one meal of the usual three, and they sang and laughed, and enjoyed the amusements the ship’s officers provided for them, while thousands imagined pictures that differed immensely from this condition of affairs. Many saw a wrecked ship, her decks awash with breaking seas, death and disaster, and for fear that the seas might be battering the steel sides of the staunch coaster.165

"

Ironically, in February 1919 the Princess Maquinna, with Captain Gilliam again in charge, also lost its propeller in the same Easy Inlet and had to be towed to Victoria. Doubly ironic is the fact that when the Pacific Salvage Company received the contract to go and find the Maquinna’s missing propeller, in March 1919, it chartered the Tees, which by then had been retired from regular service, to do the search. But after four days of putting divers down they failed to find the propeller in the 150-ft (45-m) depth.166

Because the entrance to Walters Cove, which holds Kyuquot village, is too narrow for the Maquinna to enter, she off-loads passengers and freight at Chamiss Bay, and smaller boats carry passengers and freight the 6.5 nautical miles (12 km) southwest to Kyuquot. As the Maquinna makes her way out of Kyuquot Sound, she passes the entrance to Walters Cove. Well protected from the wild Pacific storms that often rage just outside its narrow entrance, the cove is one of the safest harbours on the coast and includes a general store and a number of houses connected by a boardwalk. The east side of the cove houses a Kyuquot First Nation village. For many years fishermen in their boats sought the shelter of Walters Cove during storms, and it became locally know as “Bullshit Cove” because of the tall tales told by those fishermen while they waited out storms.

Once past Walters Island, the ship heads out into the open waters of the Pacific, heading north around the Brooks Peninsula, with Cape Cook at its northwest point, and into Quatsino Sound. Here, the Maquinna will make her final stops on the northern leg of her ten-day run.