Chapter 8: Sheltered Waters

In 1917 millions of pilchards (Sardinops caeruleus, a member of the sardine family) mysteriously appeared off the west coast of Vancouver Island. Although their usual range is the waters off California, Indigenous people of British Columbia knew of their existence through oral history, which spoke of an oily fish that appeared intermittently over the years. Local non-Indigenous fishermen, however, had not encountered these fish for a generation, and were stunned at their arrival and the sheer numbers of them. Their sudden reappearance, which was to last about thirty years, seems to have been associated with a slight increase in ocean temperature in the region. The pilchards filled the inlets up and down the west coast of Vancouver Island in massive schools. In his memoirs Tofino’s Mike Hamilton writes: “There were literally millions of tons of them. The Sound [Clayoquot] teemed with them. They made a sight to be remembered when after dark one could stand in the bow of a power boat and watch the phosphorescent millions hastening out of the way.”83 Eleanor Hancock, in Salt Chuck Stories from Vancouver Island’s West Coast described them as “bubbling silvery carpets in the inlets.”84

When the first pilchards arrived, a few salmon canneries on the coast tried to process and can them using the same methods they employed to can salmon. Customers found the pilchards unappetizing and overly oily, so the canneries began reducing (boiling down) the pilchards, extracting the oil and then drying the remains for fish meal. Each ton of fish produced 45 gallons of oil, a product used in making soap, paint, varnish, printing ink, cosmetics, salad dressings, shortening and margarine, as well as a treatment for leather. Farmers used the fish meal as a potent fertilizer or fed it to their cattle and poultry.

Before long, canneries couldn’t cope with the quantities of pilchards being caught. Seine boats averaged 50 to 200 tons with each “set” of their nets, occasionally reporting 500 tons being hauled onto one boat. To process this astounding volume of fish, by the mid-1920s, twenty-six reduction plants sprang up on the west coast of Vancouver Island, all located in the 100 miles (160 km) between Barkley Sound and Kyuquot. Construction costs for each plant could reach as much as $250,000. “Suitable sites were at a premium,” says George Nicholson in Vancouver Island’s West Coast, “requiring good penetration for pile driving, shelter for boats and docks, and above all a plentiful water supply. Construction crews could ask any price to build the reduction plants. Victoria and Vancouver shipyards worked night and day building seine boats and scows, while fishing companies vied with one another in a mad scramble to cash in on the bonanza.”85 These reduction plants employed thousands of workers, and kept a fleet of two hundred seiners, tugs and scows busy during the four-and-a-half month season when the fish stayed in the inlets. According to Earl Marsh in his West Coast of Vancouver Island: “The business grew so rapidly that in 1928 there were 22 plants in operation, consuming 80,500 tons of fish, the value of which landed at the plants being $2,563,000, which produced 3,995,860 gallons of oil, which was worth about 40 to 45 cents per gallon to the producer, and in addition 14,000 tons of fish meal.”86

The Princess Maquinna became an essential link in the pilchard industry. With so much oil and fish meal being created, the pilchard plants required regular and reliable transport for their products. The Maquinna’s cargo holds fairly bulged to overflowing on her run southbound as she called in to these busy plants and loaded up, carrying the oil and fish meal to Victoria for trans-shipment. As Bamfield’s Johnnie Vanden Wouwer attested: “In the summer, the Maquinna would load on all this herring meal and pilchard meal instead of going back down [to Victoria] empty. It made great fertilizer (and animal feed), so that paid off for them. The pilchard oil was used as paint. Real thick it was. I remember Randal painted the hospital dwelling with it. You just mixed some coloring in it and that stayed on there for years and years, but there sure was a stink to it for weeks after, especially in the sun!”87 While the Maquinna profited from carrying meal and oil to Victoria, the smells from the reduction plants tested the sensibilities of the Maquinna’s passengers. They would wake up in their cabins and know by the smell that the ship was approaching one of the reduction plants on the coast.

Heading up the Alberni Canal from Bamfield the Maquinna could potentially call at nine locations: the Indigenous village cannery and logging operations at Sarita Bay; the cannery and saltery at San Mateo; the settlements at McCallum and Ritherdon Bays; the cannery at Kildonan; the village at Green Cove; the logging camp at Underwood Cove; the settlement at Croll Cove; and finally Port Alberni itself. She seldom called at all these places on any one trip, only stopping “when business offered.”88

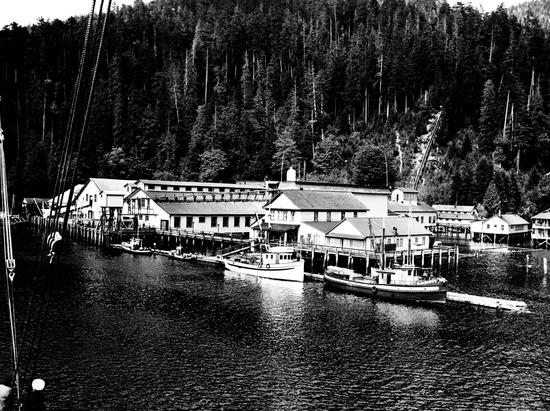

The BC Packers fish plant at Kildonan, where the Maquinna stopped on both her northbound and southbound journeys, was the biggest fish-processing plant on the west coast in the 1920s. Fish packers from the entire west coast brought salmon to this plant to be canned, and it also processed pilchards and herring. An added bonus for fishermen was the large cold-storage plant, which made ice for the many fishboats and fish packers.

Originally called Uchucklesaht when the Alberni Packing Company built the plant in 1903, the Scottish-born Wallace brothers changed its name to Kildonan, after their home in Scotland, when they purchased the plant in 1911. By the 1920s Kildonan had become a self-contained community, with a store, cookhouse, bunkhouses for both men and women, a recreation hall, its own electric light plant, water and sewage systems, and a school for the employees’ children. Many local Indigenous women from the nearby Uchucklesaht village worked there during the summer. As well, many Chinese workers arrived each season, living in their separate “China House” at the cannery, where they did their own cooking. Indigenous women and Chinese men played a central role in all west coast canneries and reduction plants; the industry would have experienced great difficulty operating effectively without them. In the 1920s the fishing industry in British Columbia employed twenty thousand people and generated millions of dollars for the provincial economy.

Having arrived at Kildonan around 5 or 6 p.m. the Maquinna takes as long as two to two and a half hours to unload goods and load her cargo at the cannery. Then she casts off and backs into Uchucklesit Inlet, and continues her journey up the Alberni Canal.

On a summer evening this next part of the journey proves a delight for the Maquinna’s passengers and the calm waters come as a welcome relief after the exposed waters of the open Pacific. Tofino’s Tony Guppy offers a lovely description of the trip down the canal:

"The heavily timbered shoreline and islands that we sailed past could hardly be matched anywhere in the world for scenic beauty. Clear mountain streams cascaded like jeweled necklaces down the steep hillsides and rocky cliffs. Molded and carved by volcanic and ice age activity, this rugged Pacific coast was wonderfully formed, with long deep inlets of water reaching far into the mountains. Loggers had built wooden flues in some of the mountain streams to carry the huge logs down the perilous slopes to the sea. To see the logs come crashing down from these heights like huge arrows from the clouds was something to behold! The loggers working on these mountain slopes would have appeared like tiny insects to people watching from the ship below. These were the pioneer woodsmen who harvested the trees that supplied the numerous sawmills in operation along this coast. Hand-loggers they were called. Their methods had to be innovative and highly adaptive in order to log in the dense forests that covered this rugged mountainous terrain.89

"

In late evening, the Maquinna arrives at the largest town on the west coast, Port Alberni. Settlers began to arrive in the area when Captain Edward Stamp built a sawmill here in 1860 “... erected in a most solid fashion, and at a heavy outlay, by English labourers, and with English machinery.”90 Although the mill did well for a number of years, it eventually closed because of a lack of timber, which seems odd given the abundance of trees lining the sides of the canal and on the mountains behind. But in those early days of hand logging, before steam- and gasoline-driven machinery, most of the timber remained inaccessible except along the fringes of the coastline. Later, when mechanized logging practices developed, the huge trees on the upper slopes became easier to harvest.

In 1863 Edward Stamp left Port Alberni for Burrard Inlet, Vancouver’s harbour, where he set up another sawmill, Hastings Mill. The settlement that grew around the mill eventually grew to become the city of Vancouver. His chief forester, Jeremiah (Jerry) Rogers, accompanied him and logged in an area locally called Jerry’s Cove, more familiarly known today as “Jericho,” now a sought-after area of the city.

Though this first Port Alberni enterprise did not live up to expectations, traders, missionaries, prospectors, fishermen and farmers slowly began to put down roots at the eastern end of the canal, and a small town emerged. In 1892, the first pulp mill in the province opened there but since “it made paper from rags rather than wood,”91 this unlikely venture closed in 1896. Another fifty years would pass before Bloedel, Stewart and Welch opened a modern pulp and paper mill—using wood chips—in 1946. This became the town’s main economic engine for many decades, and its main source of employment.

Port Alberni differed from all the other settlements on the west coast served by the Maquinna in that it had optional means of travel, other than by water. In 1886 a road, and by 1911 a railway, linked the community to Parksville and Nanaimo on the east side of the island. Long before settlement, the Indigenous peoples followed their own trails through the mountains of central Vancouver Island in order to trade with First Nations on the other side. Some early settlers used those existing trails to make their way over “the Hump,” as the locals call the highest point of the pass through the mountains immediately east of Port Alberni. Travelling from Port Alberni to Nanaimo by train linked westcoasters to an easy boat connection down the Gulf of Georgia to Vancouver and the Lower Mainland. Because of this, Port Alberni became a transportation hub for many on the outer coast. People living in remote communities along the coast, as well as local businesses requiring goods from the Lower Mainland, often had those goods delivered to Port Alberni and then transported on the Maquinna, making this a busy stop for the ship. Port Alberni also possessed a modern hospital that took patients from isolated settlements on the coast, with the faithful Maquinna often acting as a hospital ship to transport the sick and injured.

After two hours of loading and unloading goods and passengers, the Maquinna sets off back down the Alberni Canal, making stops in the dark. This calls for careful navigation. Years later, on the night of January 18, 1934, Captain Robert “Red” Thompson chose to remain at the dock in Port Alberni because of the heavy fog that the ship had encountered on its journey up the Alberni Inlet (as it had been called since 1931) the previous evening. With the weather clearing, at 4:44 a.m. First Officer William “Black” Thompson, in charge of the bridge, eased the ship away from the dock, ordering the engine room to proceed at half speed out of the harbour. While gingerly making her way in the darkness, at 4:52 a.m. the Maquinna acknowledged a whistle blast from the MVMirrabooka, a Swedish ship off her port bow, and changed course one degree. Almost immediately after changing course, First Officer Thompson and the lookout at the bow simultaneously spotted the silhouette of a dark object lying dead ahead with no lights showing. Thompson immediately ordered the engines full astern but the Maquinna struck the SSMasunda, an anchored, 5,250-ton British steamer from Glasgow, three times the size of the Maquinna. Despite having put the engines in reverse the Maquinna hit the Masunda in the bow area, causing considerable damage to both vessels.

After assessing the damage, the Maquinna set sail for Victoria at 5:04 a.m., arriving in Victoria at 8 pm. A few days later she was hauled out at the Victoria Machinery Depot where repairs costing $16,000 took place over the next twenty days. The CPR sued the owners of the Masunda for damages and at a trial held at the Royal Court of Justice in London on October 10, 1934, Justice Bateson, relying only on the written evidence and witness affidavits, found against the company stating that: “I have come to the conclusion that the vessel had her lights properly exhibited and burning brightly and that the ‘Princess Maquinna’ is responsible for the accident.”92 Yarrow’s Shipyard repaired the Masunda at a cost of $24,929, taking twenty days to accomplish the task. Needless to say the CPR was not happy with the judgement but, on the advice of counsel, decided against appealing.

Alder Bloom, a young lad from Saskatchewan who travelled on the Maquinna on a rainy August night in the 1920s, eloquently described the return journey down the inlet in an article he wrote:

"I stood on the deck at midnight as the ship left the dock, watching the Port Alberni lights disappear in the gloom. The water was smooth in Alberni Inlet, and the ship made a pleasant swishing sound as it moved along through the dark. I could see the shape of the tall, steep mountains on both sides of the Inlet, starting at the water’s edge and reaching to the sky. I climbed into my bunk and slept the sleep of the innocent... The Maquinna had three or four stops in Barkley Sound. The main one was Kildonan, the BC Packers fish plant... BC Packers had another reduction plant not far away at Ecoole, and Nelson Brothers had a reduction plant at Toquart. This was my first sight of fish plants and I wasn’t much impressed. But if the shore plants, with their white-washed, board-and-batten walls and rusty, galvanized iron roofs, weren’t much to look at, the fish boats were another story. They were kept in good shape, well painted and clean, and looked ready to take on the West Coast storms.93

"

Occasionally, on her return journey down the Alberni Inlet, the Maquinna might carry a load of coal that had come by train to Port Alberni from the coal mines around Nanaimo, and sometimes she carried lumber to be off-loaded at Bamfield. Long time Bamfield resident Johnnie Vanden Wouwer recalled:

"The coal [for the Bamfield Cable Station] came from Nanaimo on the Maquinna. She would stay all afternoon unloading the fifty tons from the forward hold. That was all they had was the forward hold, you see. The fifty tons would put her down quite a bit and after they were through, she’d be up by about two feet... There’d be fifty tons of coal on the dock, in a pile about 20 feet high, that the Chinamen had to load in wheelbarrows and send up in the trolley, which took about 1/2 an hour to get to the top. And then they had to unload it into a big bin.94

"

With the coal unloaded the Maquinna backs out of Bamfield and steams into Barkley Sound and through the Broken Group of islands where she will make only a few stops as she heads north for Ucluelet, her next major port of call.