Chapter 13: Nootka Sound

As the Princess Maquinna steams toward Yuquot she crosses the mouth of Nootka Sound. For passengers who know their British Columbia history, these are highly significant waters, for on March 29, 1778, momentous events took place here.

After sailing across the Pacific Ocean from Hawaii, while on his third circumnavigation of the globe on a mission to find the Northwest Passage, the British naval captain James Cook sailed into Nootka Sound. He sought shelter to repair his two storm-battered ships, HMS Resolution and HMS Discovery. Having been greeted by some of the Mowachaht men in canoes, who thought the newcomers “were the dead returning... in floating houses,”142 Cook sailed past the village of Yuquot, anchoring in a small cove sheltered by an island. He named these landmarks Resolution Cove, after his ship, and Bligh Island, for one of his midshipmen, William Bligh, later the infamous master of HMS Bounty.

Cook and his men stayed in Nootka Sound for over a month making repairs, cutting new masts and spars, brewing spruce beer and trading with the local Mowachaht people and their mighty chief Maquinna. As the most powerful chief on the west coast, he could muster an army of 300–400 warriors when needed, and presided over an estimated 1,000 people at Yuquot, the tribe’s main summer residence. Other tribal members lived in various other summer encampments. In winter Maquinna and his people lived in Tahsis and in other smaller villages well inside Nootka Sound, away from winter storms on the outer coast. In spring the Mowachaht moved back to Yuquot to be nearer the ocean, where they would hunt whales, northern fur seals and sea otters in the summer months.

The Indigenous people particularly prized items they could not produce themselves: industrially manufactured, mostly metal, items such as knives, chisels, nails, needles and buttons. Cook’s men traded a large quantity of such items for a total of three hundred sea otter pelts, initially using these soft furs as mattresses in their hammocks. Much later on their journey, when they arrived in Canton, where such furs were very rare and highly valued, they traded them at a profit and bought porcelain, silks and spices, which in turn they later sold in England for a huge profit over the cost of the original knives and chisels. Their returns, in some cases twice the annual pay of a seaman, precipitated the sea otter fur trade that would bring avid traders from many nations to Nootka Sound and to the entire northwest coast of North America.

Yuquot, on Nootka Island, can rightly claim to be one of the most beautiful and intriguing locations on the west coast. As the Princess Maquinna rounds the Nootka Lighthouse on Hog Island (now San Rafael Island) and enters the cove, passengers pass the site of Fort San Miguel, built on San Miguel Island by the Spanish. In 1789, Spanish naval ships arrived from Mexico, more than a decade after Cook’s visit, and occupied the island in an attempt to lay claim to the area, which Cook had already claimed for Britain. This incursion precipitated a diplomatic squabble that brought Britain and Spain to the brink of war. The Nootka Convention of 1790 brought an end to the wrangle, which eventually saw Spain pay restitution to Britain for ships she had damaged, and relinquishing all claims to the west coast of North America.

Once inside the cove, visitors see ahead of them a long curving beach above which “is a row of Indian houses, about 100 yards above the shore line,” as Inspector Brodie writes in his 1918 report. “In front of the village they have two of the finest totem poles on the Pacific Coast. One is crowned by a figure of Capt. Vancouver in a grotesquely painted black silk hat. They have a large assembly hall [a longhouse] in which they hold festivals, etc... To the right of the village there is a small clearing where a little church is situated.”143 In 1889 Father Brabant built the church Brodie refers to.

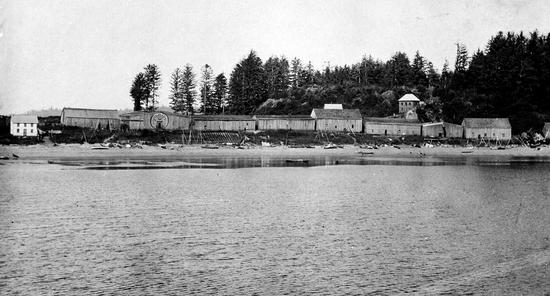

Brodie’s expansive report continues, pointing out that the first European ship ever built in British Columbia was built here at Yuquot. Captain John Meares arrived at Nootka in 1788, bringing with him twenty-nine Chinese workers, and set them to work building the 45-ton North West America in a small cove inside Yuquot. Once launched, he employed it trading for sea otter pelts up and down the coast.

What caught Brodie’s attention in particular was the graveyard, to him “one of the most interesting places on the Pacific Coast.” Used by the Mowachaht people, the individual burial plots all had individual fences:

"There are numbers of small houses built over the various graves. One house in particular is very amusing. After completing the house and shingling it all, including the roof, two window frames with four panes of glass in each one, are carefully nailed on top of the shingles on the room, two on each side, so as to give the necessary light within. One grave is of particular interest. The plot is of a fair size with a good fence around it. A monument in the centre informs you that this is the son of Chief Napoleon Maquinna. It is customary for the Indians to make sacrifices for the dead, so the Chief has placed on each side of the grave two very fine dugouts. At the back of the grave in the centre of the fence, is a small model of a ship which the boy once played with, and on each side are the ends of an iron bedstead, with some wash basins and some other trinkets. On another grave of an Indian woman is a sewing machine, wash basins and baskets, together with several other small effects. One man who died has over his grave a bicycle pump, a lantern, and old gas tank, lunch basket and some wash basins. Another has a gramaphone [sic]. Sewing machines and bedsteads seem to be quite popular. One little child’s grave has a go-cart on top of it. Altogether the graveyard is rather pathetic, and I am afraid if many tourists visited it they would steal some of the baskets and other articles as souvenirs, although it would cause a great row among the Indians.144

"

On August 12, 1924, the Princess Maquinna arrived at Yuquot with then Lieutenant Governor Walter Nichol, Dr. C.F. Newcombe of the Provincial Museum and Judge F.W. Howay of the Historic Sites and Monument Board of Canada, as well as other dignitaries and onlookers. The lieutenant governor unveiled an 11-ft (3.3-m) cairn commemorating Cook’s “discovery” of Nootka Sound. Tofino author Dorothy Abraham wrote of the event in her book Lone Cone: “When we arrived at Nootka, Indians in their war canoes came out and encircled the ship [the Princess Maquinna]. They looked quite frightening in all their war paint, fish blood etc. The cairn to Captain Cook was unveiled with an impressive ceremony, and one tried to visualize Nootka as it had been in his day. Later the Indians, adorned in their weird and grotesque garments sprinkled with duck down and wearing alarming head pieces, put on some excellent Potlatch dances.”145 Gillam’s friend Father Charles Moser acted as interpreter for Nichol and Nootka chief Napoleon Maquinna, descendant of the original Chief Maquinna. “The officials of the CPR company allowed the steamer to remain at Nootka Sound for an extra half-day in order that ample time might be provided for the ceremony.”146

After stopping at Yuquot on our imagined 1924 trip, the Maquinna sets off again for a run of 1.75 nautical miles (3.2 km) to the Nootka Cannery, opened in 1917 and situated in Boca del Infierno Bay farther into the Sound. There she picks up cases of salmon and pil-chard products.

Beginning in the 1930s, the Maquinna would leave Nootka Cannery and, instead of going back out into the Pacific, would head deeper into the sound toward Tahsis, where the Gibson brothers were then engaged in logging. If we take a diversion here, a few years ahead of our current journey, we can revisit that era when logging thrived on the fringes of these inlets, where small independent hand loggers, or “gyppo loggers,” operated from float camps.

“The word ‘gyppo’ has been used in many ways to describe many things about our logging industry,” writes Bill Moore. “It generally is used to describe a logger who is, among other things, ‘a loner,’ an innovator who can patch things up and make them ‘run,’ an ‘owner of a very small camp’ or a ‘maverick.’ To operate a camp in a gyppo way could mean to operate on the cheap, to use haywire equipment or to simply operate with a small crew.”147

Al Bloom describes his journey up Tahsis Inlet on the Maquinna in 1937 when he witnessed these gyppo outfits, hand-logging the side hills in the days before logging trucks and chainsaws.

"The slopes were covered with trees—fir, hemlock, cedar—and a lot of scrub bush, right down to the high water mark. I soon saw my first small, gyppo logging show (it was anything but small to me) where everything was on big log floats, jill-poked [secured] from shore by long logs, and anchored in place with cables running ashore and tied to big stumps. The cookhouse and bunkhouse were on floats, and on another float there was an A-frame, made of two heavy poles about one hundred feet high, lashed together at the top and held upright by several cables. At the bottom of the A-frame was the donkey engine, powered at first by a steam boiler, but later by the more efficient diesel engine, and connected to a three-drum winch. One drum held the straw-line, the second the heavier haul-back line, and the third the heavy mainline.148

"

The three cables that ran from the three drums on the float were essential for dragging the cut logs down the mountain slopes to the booming ground in the water below.

"The A frame shows were tough to work on; you had to be a mountain climber in heavy caulk boots, able to scramble over and under logs, pulling and pushing heavy chokers into position, and getting out of the way before the whistle punk started a load on its way down hill. As the Maquinna moved through the quiet waters, we passed a couple of these floating rigs, and could see many places where they had been working, taking the easy-to-get logs along the shore. The sides of the mountains were stripped clean of all greenery as far as the mainline cable could reach—usually a few thousand feet—but the hills and valleys away from the water were left for a different breed of logger to come later with his mechanical equipment on caterpillar tracks.149

"

When Al Bloom made this trip on the Maquinna, in 1937, the Gibson brothers from Ahousaht had branched out and were now running a large logging operation near Tahsis, at the head of Tahsis Inlet.

"This camp was all on big floats, one of the Maquinna’s regular stops. There was Gordon Gibson standing on the float, a big cigar clamped in the corner of his mouth, but it didn’t stop him from roaring a greeting to the captain on the bridge. He was big, burly, loud, the typical bull-of-the-woods if there ever was one, in his bone-dry clothes with the pants stagged [cut] halfway up his legs, and his jacket wide open showing the bright, wide braces that he used to hold his pants up. His feet were shoved into high-top caulk boots with the tops wide open and the laces flying in the breeze, so he could kick them off in a hurry whenever he entered a camp building... When the Maquinna docked he would go on board, carrying his caulk boots in his hand, and head downstairs to the lounge, where he put his stocking feet up on a coffee table in a most relaxed manner and enjoyed an hour’s conversation with the people around him. The oldest brother, Clarke, took care of the Vancouver office. They couldn’t lose, with Gordon to ramrod and bulldoze his way through any job around the woods or on the boats, and the others [his older brothers Clarke, Jack and Earson] to smooth over the rough edges he left along the way.150

"

Later still, in 1945, the Gibson brothers would build a huge sawmill in Tahsis, bringing great prosperity to the small village and providing the Maquinna with even more business.

Finished with Tahsis, the Maquinna heads back down the inlet before turning up Tahsis Narrows, which connects Tahsis and Esperanza Inlets and separates Nootka Island from Vancouver Island itself. Just after turning into the narrows and running across Blowhole Bay, the ship reaches the Ceepeecee pilchard cannery, built in 1926. One of the most curious names on the west coast, the cannery derived its name from the initials of its first owner, the Canadian Packing Company. In 1934 Richie and Norman Nelson bought the plant and hired Dal Lutes to manage it. Al Bloom wrote:

"The Nelson brothers seldom came to Ceepeecee, as it was a two-week round trip on the Maquinna, but let their manager run the plant. Lutes was a character in his own right with a voice and vocabulary that would do justice to a mule skinner, a job that he handled in his younger years when he freighted from Steveston to Vancouver over a wagon road now known as Granville Street. He ran Ceepeecee as if he owned it, and when the only contact with head office was a shortwave radio, it is small wonder that this should be so. To all and sundry, Lutes was Mr. Ceepeecee, loved and respected by many, hated by others. When the Maquinna docked, the tourists would flock ashore to stretch their legs. To reach the local store they had to follow a ten-foot-wide plank walkway between the cannery and the reduction plant, plowing their way through various strong smells produced by the reduction plant and by rotting offal on the beach. They covered their noses with perfumed handkerchiefs and rushed through this section, hoping to reach fresh air again.151

"

A ten-minute boat journey northwest of Ceepeecee lies the Esperanza Mission Hospital, established in 1937 by Dr. Herman McLean and the Nootka Mission Association, an offshoot of the Shantymen’s Christian Association. The Maquinna does not make regular stops at the hospital itself, but drops off the mission’s mail and supplies at Ceepeecee where the mission’s own boats—used for medical and missionary work—pick them up.

Underway again, and still on our time-travel to the 1930s, the Maquinna steams out of Hecate Channel and into Zeballos Inlet where she turns northeast toward the gold-mining town of Zeballos at the head of the inlet. Prospectors would find gold here in 1936, setting off a spectacular gold rush in the midst of the Great Depression in one of the wettest places on the west coast.