Chapter 10: Shipwreck and Safe Harbour

In October 1915, only two years after the Princess Maquinna began her regular runs up and down the west coast of Vancouver Island, she ran into a particularly powerful storm. Fatefully, so did the three-masted Chilean ship Carelmapu, in ballast from Hawaii and bound for Puget Sound to pick up a load of lumber. Normally, the two ships should not have come near each other, but in such a storm, anything could happen.

On October 18, the Carelmapu reached the entrance of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, where her captain, Fernando Desolmes, fired a succession of five flares requesting a tug to tow his ship into port. While waiting all day for a tow, a strong southeast gale, packing winds of 75 to 80 knots, began driving the ship northwards up the west coast. Desolmes shortened sail, trying to hold her, but the next day, near Pachena Point at the entrance to Barkley Sound, a vicious blast blew out most of his ship’s sails. This forced him to hoist distress signals as the wind continued to drive his thirty-eight-year-old ship up the coast until it reached Lennard Island near the north end of Long Beach.

With his ship’s sails in tatters, Desolmes ordered his crew to throw two anchors into the 240-fathom (440-m) depth of water in an attempt to hold the ship and prevent her from going onto nearby Gowlland Rocks. Other members of the crew attempted to launch a lifeboat, only to have it swamp, hurling the occupants into the breakers.

As the imperilled Carelmapu headed toward the rocks, Captain Gillam and the Princess Maquinna neared Tofino on their regular voyage southbound on their west coast route. After stopping there, Gillam made the decision to “make a run for it,” despite the weather, and continue journeying south. If the gale proved too severe when he reached open water, just past the Lennard Island Lighthouse, he planned to return to the shelter of Tofino until the storm abated. When the Maquinna, with fifty passengers aboard, reached Lennard Island at the south end of Templar Channel, where the relatively calm waters of the channel gave way to open ocean, Gillam reported that he could see the sea breaking in a line as far as Cox Point. After consulting with his officers, he decided to head back to Tofino and wait out the storm rather than endanger his ship and passengers. Before he turned his vessel around, however, a lookout spotted the Carelmapu some distance offshore flying flags upside down, the international distress signal. “Then we had no alternative but to keep on in the face of anything, as we knew that lives were in danger,” Gillam later told the Victoria Daily Colonist.101

With waves breaking over the pilot house and spray flying over the masthead, Gillam steered the Maquinna to within 150 yards (140 m) of the stricken ship. “Maquinna handled splendidly, and at full speed she plunged into the tremendous seas, first perched on the crest of a great wave and then down in the abyss, skimming over the frenzied water like a duck,”102 Gillam reported. He then turned his ship seaward into the mountainous Pacific waves and set his anchor. With the ship’s engines turning at half revolutions to hold her into the waves, he ordered oil poured overboard from the fuel tanks to help calm the raging seas. As the sea calmed slightly due to the oil, the Chileans lowered seven men into a second lifeboat—the first having foundered—and they began valiantly rowing toward the Maquinna. But the strength of the waves exhausted the rowers before they could reach a lifeline thrown to them from the stern of the Maquinna, and the small boat overturned, throwing its occupants into the churning sea. None survived. Some of the crew of the Maquinna offered to try launching one of her lifeboats in an attempt to save them but Captain Gillam, deeming it too dangerous, refused permission.

Suddenly, despite the engines keeping her heading into the oncoming sea, a massive wave hit the Maquinna with such impact that the winch holding the anchor chain on the forecastle deck began buckling the deck plates under the strain, and the steel decking began to lift. The same wave tore the Carelmapu from her anchors, leaving her entirely at the mercy of the storm, heading toward Gowlland Rocks. Realizing the hopelessness of the situation, Gillam then ordered First Mate C.P. Kinney to go to the forecastle deck and cut the Maquinna’s anchor chain with a hacksaw. Kinney had to be lashed down and held by crewman Harry Hamilton to prevent him being washed overboard as he laboured to cut the huge anchor chain. It took Kinney an hour and a half to cut through the iron chain-link, 1.5 in (4 cm) thick, before the anchor let go, at which point Gilliam reluctantly pointed the Maquinna out to sea, leaving the Carelmapu to her doom in Schooner Cove. As he headed out to sea Gilliam looked back to see Desolmes waving a despairing farewell, and the Maquinna’s passengers watched in horror as the mizzen mast of the shipwrecked vessel ripped off, tossing two of the remaining men overboard into the sea. Desolmes released himself from the railing, genuflected, and dropped into the ocean. Against all odds, he made it to shore.

Gillam had done all he could under the perilous circumstances. “Rather than have the bow ripped out of her I ordered the 60 fathoms [110 m] of anchor chain to be severed. With nothing between us and the reefs, I was forced to navigate Maquinna out to sea... I was in charge of a large number of passengers and could not take any more risks. We steamed from there direct for Ucluelet and remained there overnight,” Gillam told the Colonist. “Never in all my long experience in west coast service have I been called upon to nurse a ship through such terrible seas.”103

Amazingly, five of the twenty-three-man crew of the Carelmapu, including Captain Desolmes, survived the sinking, along with the ship’s Great Dane, Nogi. Long Beach settler John Cooper buried eleven of the bodies that eventually washed up on the shore, and later wrote: “Nobody knows where they are but myself.” Captain Desolmes and one of the survivors, Rodrigo Diez, stayed at Long Beach with Cooper; the other three went to the hotel at Clayoquot, in care of the Tofino lifeboat crew. “All were in very bad shape,” commented Cooper. He adopted Nogi, who wore a brass collar with the name of the ship on it, but two years after being saved “a souvenir hunter shot him for the Carelmapu-inscribed brass plate on his collar.”104 The stricken and broken remains of the ship remained on the Gowlland Rocks for many years before storms eventually tore her off the promontory.

The Carelmapu incident put the Princess Maquinna and Captain Gillam in the public eye as never before. “The gallant skipper has nothing but praise for his officers and members of the crew, but he is very modest in taking any credit himself for the part played by Princess Maquinna in stretching out a helping hand to the disabled ship... Princess Maquinna did all that was asked of her and Capt Gillam is proud of the vessel and the way in which she handled herself under the prevailing conditions,”105 declared the Colonist newspaper. Sometime after the incident, when the Carelmapu survivors reached Victoria on the Maquinna, Rodrigo Diez, who spoke English, told a reporter: “The Maquinna captain was magnificent. I’ll never forget his courage in bringing his ship right into the breakers. I shudder to think of it.”106

For summertime tourists, steaming north from Ucluelet on our imagined trip in 1924, the desperate peril of the Carelmapu may be almost impossible to imagine. Though this section of the trip is in open waters, despite the rolling of the ship, fine weather allows passengers to sit outside on the upper deck in chaise longues, reading and chatting, as they watch the passing scenery. They might even enjoy a game of shuffleboard or quoits on deck. Al Bloom describes a trip on the Maquinna from Ucluelet to Tofino:

"On leaving the sheltered bay at Ucluelet, the Maquinna made a sharp turn to the right and sailed between jagged rocks that looked very dangerous to a landlubber. Waves were breaking on these rocks and sending spray high into the air. The ship began to roll slightly. As we cleared the rocks and turned in a northerly direction again, we were out on the open ocean, and the long Pacific swells caught the ship broadside. She rolled along in great style. To the west, except for a few trollers that kept disappearing in the trough, only to reappear again on top of the giant waves, there was water as far as the eye could see. To the east was the now-famous Long Beach, although it was many years before the road from Alberni would be built and tourists would flock to Pacific Rim Park. In my time, Long Beach was used as a road between Ucluelet and Tofino, and it made a fine speedway, well maintained by the waves. There were few cars around, and the truck drivers who used the route had to watch for tides. A breakdown with tides coming in spelled doom for the truck; it would be sucked down and covered with sand in short order... Our rolling ride only lasted a couple of hours and was quite pleasant, but during storms this was a rough stretch to travel. The waves hit slightly on the stern side and gave the boat an unpleasant twisting, rolling motion.107

"

After rounding Lennard Island Lighthouse, the vessel turns into Templar Channel. There the ship’s officers might point out to interested passengers where the sailing ship Tonquin met its end, just off the east coast of Echachis Island, in 1811. The Tonquin, owned by John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company, had arrived from Astoria, Oregon, to trade for sea otter furs with the local Tla -o-qui-aht people. For various reasons trading negotiations went catastrophically wrong, angering the Tla-o-qui-aht who attacked the ship, killing all but six of the ship’s company. The next day some three or four hundred Tla-o-qui-aht returned to the ship with plunder in mind, but the wounded ship’s clerk, James Lewis, who had remained hidden aboard, took drastic action. He lit the nine thousand pounds of gunpowder stored in the Tonquin’s hold, blowing up the ship and killing himself and over two hundred of the Tla-o-qui-aht aboard.108 This incident marked the end of the maritime sea otter fur trade, which had flourished since Captain Cook arrived on the west coast in 1778 and which had all but annihilated the sea otter population along the coast.

Rounding Grice Point, the Maquinna approaches the village of Tofino, where she always receives a warm-hearted welcome. The whole village turns out on “Boat Day” to greet the ship. As in every community on the coast apart from Port Alberni, no road links this village to the outer world. Work on the road to Ucluelet has been staggering ahead in fits and starts for years, but it is still best described as a rutted path, and won’t be completed until 1928. “So the arrival of the Maquinna in Tofino, as elsewhere on the coast, is a social and economic highlight like no other...”109 In her book Lone Cone, Dorothy Abraham recalls how the Maquinna once unexpectedly arrived in the middle of the Sunday church service. When the congregation heard the whistle they all rushed out and headed for the wharf, leaving the minister preaching to empty pews. Schoolchildren also ran from their classrooms once the whistle sounded.

In 1924, when our imagined voyage takes place, the village of Tofino held a population of just over one hundred Scots, English, Scandinavian and Japanese settlers. The Tla-o-qui-aht village of Opitsat lay across the harbour, with a population of around one hundred and fifty. By the 1920s, the village of Tofino boasted a lifeboat station, two shops—Towler and Mitchell’s, and Elkington’s—the St. Columba Anglican church, a school, the Wingen boat yard and machine shop and, about 12 miles (20 km) up Tofino Inlet, the Clayoquot Fish Cannery. Fishboats line the shore in front of the village and when the Maquinna docks small boats converge from all over the harbour, and from up the nearby inlets, to collect their mail and parcels, and greet visitors. The Tla-o-qui-aht carvers and weavers sell baskets and carvings to visitors as they disembark.

Ron MacLeod, who was born in Tofino where his father Murdo served as fisheries officer, provides a wonderful description of what the Maquinna’s arrival meant to the village:

"Mail, freight and passengers were brought into Tofino by a Canadian Pacific steamer, for years the Princess Maquinna, on the 3rd, 13th and 23rd of each month. On its return journey to Victoria three days later, it would pick up outgoing passengers, cargo and mail. A $10.50 fare would cover the cost of the two-day trip to the provincial capital, Victoria, if one shared a stateroom... The officers and many of the deck and engine room crews were Scots from the Hebrides or Orkneys and a young traveller with a name like mine would be shown a great time on the trip. The arrival of the steamer was always an event. Tofino locals and Indians from the villages would gather on the government wharf to catch the excitement of the day: freight and mail unloading; salesmen coming off with their large sample cases and rushing to cover the two general stores in the limited time before the ship sailed on; a host of tourists in summer; travellers to up-coast communities enjoying a brief visit on the dock with friends. Indeed, a veritable feast of new faces and body shapes and sizes on which to make comment. In summer, Indian women would take up station on the wharf and sell woven basketwork, carvings and other artifacts. Up and down the wharf would trundle handcarts carrying newly arrived freight to the two stores. A hive of activity! How empty the government wharf seemed when the Princess Maquinna pulled out!

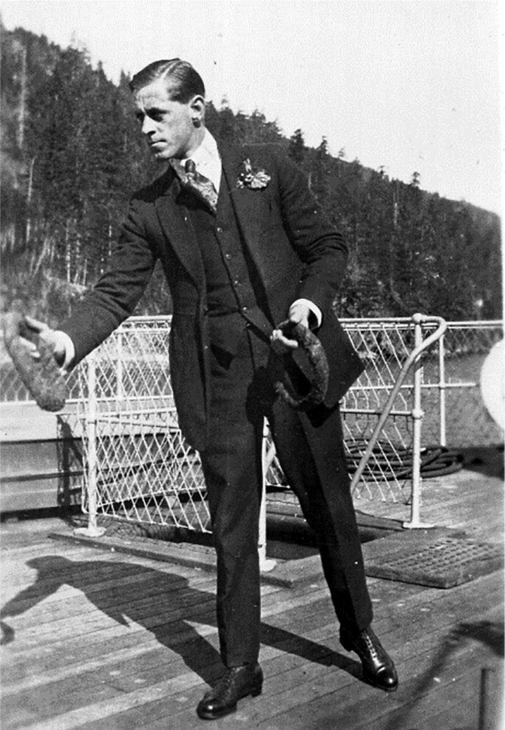

Marriages in Tofino were often timed so the newlyweds could leave on the southbound trip of the Princess Maquinna. Celebration of the rites would be followed by a dinner held in the Community Hall, the larger of the two halls in the village. Practically everyone in the village would be invited to these events. Money may have been scarce but the generosity of the community was rich when it came to getting newlyweds off on the right foot. By midnight, the Maquinna would arrive and the couple would board the vessel under a shower of rice and hearty good wishes for a joyous honeymoon.110

"

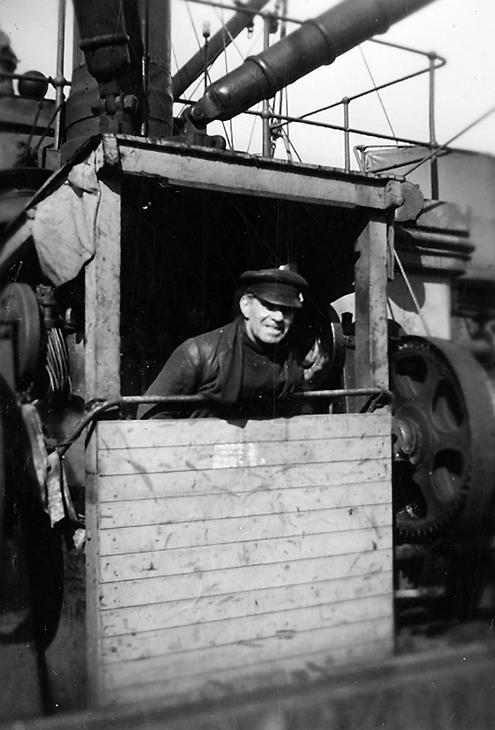

For boat builder Hilmar Wingen, who owned the Tofino Machine Shop and was renowned for building some of the finest fishboats on the west coast, the arrival of the Maquinna played an integral part in his business. She transported much-needed supplies and parts to him from Victoria. “We would take our truck onto the dock and winch man ‘Shorty’ Wright would drop the parts right into it,” said Hilmar’s son, Bob. When the Wingens had a hull ready to accept its engine they would bring it alongside the Maquinna and Shorty would drop it right into the hull for them. “Once it was in the right place Dad and our crew would mount it in place. It saved us a whole lot of time and trouble,” remembers Bob, who would later own the shop. “Shorty was a past master at loading and unloading. He wasn’t very big and you’d wonder how he did it. He was one of a kind. Dad always made sure Shorty got a bottle of Scotch for his efforts.”111

Tofino didn’t have a liquor store in those days and people in the community had to send their orders for whatever they needed down to Port Alberni on the Maquinna’s southbound run. On the next trip up coast, all the booze orders came back on a pallet that was lifted off the ship and put into a locked warehouse. “People came and picked their orders off the pallet and nothing was ever taken,” remembers Wingen. “A few days later there would be a bottle of rum or the like sitting there that someone hadn’t picked up yet, but nobody touched it. Christmas time was a particularly busy time for the Maquinna bringing booze to people all up and down the coast.”112

Johnnie Vanden Wouwer relates how some of the liquor arrived in Bamfield: “About every month the people living next door, they’d get a box of whiskey and a barrel of beer in on the Maquinna. Talk about ‘roll out the barrel’! They were long-neck bottles, packed in straw, and how they fitted them in there is beyond me. These barrels were darned heavy. I remember him [the neighbour] rolling one up the approach to the house. They were staved barrels, quite thin, especially made for this, you know, because they couldn’t hold water. When the bottles were empty, they threw them out the back. There was beer bottles back of the house about six feet thick!”113

For Tofino’s children the arrival of the Maquinna brought unimaginable delight. “All of us kids wanted to catch the rat line,” recalls Ken Gibson. “We’d hear the whistle out in the harbour and just ran like heck down to the dock to where the Maquinna was coming in.” The rat line, with a monkey’s paw at the end (a heavy ball of spliced rope shaped like a ball) would be thrown onto the dock by a crewman for the lads on the dock to catch and haul in. Attached to the rat line, the much heavier and robust hawser had to be handled by grown men, but the local lads felt that by catching the rat line they were “bringing the boat in.”114

Once the boat had been secured, and the gangplank was in place, the children would rush onto the boat heading for the commissary in the main lobby. There they would spend their saved up nickels and dimes buying sweets and comic books to tide them over until the next visit of the Maquinna. With candy and reading material secured the children returned to the dock to watch the loading and unloading. Sometimes a car or a truck would swing out onto the dock in a specially made sling, or a cow, or a load of hay, or perhaps a load of furniture. One newlywed couple’s furniture arrived with two single beds, causing no end of discussion in the community.

The Maquinna seldom ventured up Tofino Inlet past the government dock, although there were exceptions. In its September 30, 1917, issue, the Colonist reported the Princess Maquinna travelling about 11 nautical miles (20 km) up the inlet to Mosquito Harbour, the site of the failed cedar shingle mill, which had closed in 1907. There she loaded “about 2 million shingles,” which she took to Seattle for the Sutton Lumber Company. Before the mill shut, it had shipped most of its product out on the freighter Earl of Douglas for sale in New York, but huge piles of shingles were still left on the dock at Mosquito Harbour, and remained there for ten years until the owners arranged for the Maquinna to pick them up. On another occasion, according to Tofino resident Ken Gibson, the Maquinna made her way up the inlet to the Clayoquot Cannery at Kennedy Falls. Unfortunately, her mast severed the overhead telegraph wire that ran from the cannery to Long Beach. The smaller Tees regularly made trips to the cannery prior to the arrival of the Maquinna in 1913. Her larger size clearly made the journey up the inlet more challenging.

With passengers and freight off-loaded, the Maquinna steams five minutes—the shortest leg of her journey—across Tofino harbour to Clayoquot on Stubbs Island. Clayoquot preceded Tofino as the first European settlement in Clayoquot Sound; a trading post was first established there in 1854. A long sandy beach provided easy and safe canoe access for First Nations people coming to trade their furs. Over time, the trading post gave way to a store, and later a hotel and a long curving wharf, complete with rails and a trolley that carried goods and luggage to and from the ship to the store and hotel. Clayoquot even had a jailhouse and a resident policeman at one time. By the 1920s a settlement of Japanese fisherfolk lived there, one of three such settlements in the area.

As more settlers arrived in the area in the early decades of the twentieth century, Tofino slowly outstripped Clayoquot as the main commercial centre of the region. However, the Maquinna continued to pay short visits to Clayoquot until the very end of her days in the 1950s, serving the hotel and the handful of people still living there.

On the very short leg of the journey between Tofino and Clayoquot the Maquinna’s helmsman had to be on his toes, for a number of reasons. First, Tofino Inlet is infamous for its sandbars and shoals, invisible in the days before radar when fog shrouded the area: “the Princess Maquinna sometimes had to anchor until the fog lifted because of the sand banks and strong currents that abound in the area.”115 Secondly, and very importantly, the Clayoquot Hotel possessed the only liquor outlet between Port Alberni and Port Alice. “It was a particularly busy place, especially on a Saturday night,” wrote Neil Robertson. “If the Maquinna was crossing from Tofino to Clayoquot shortly after closing time she had to make her way through an armada of small boats and canoes making their unsteady way back to Tofino.”116