Chapter 3: First Stop

Returning to our imagined summer cruise in 1924, once the ship sails past the entrance to Esquimalt Harbour, she continues offshore of the Esquimalt Lagoon and Royal Roads. If it was daytime instead of 11:30 in the evening, passengers could have glimpsed the palatial, forty-room Hatley Castle, stately home of coal baron and former BC premier and lieutenant governor James Dunsmuir. Although Dunsmuir died in 1920, four years later his widow still lives there. In 1940 the Department of National Defence would purchase the property, turning it into the Royal Roads Military College, and later the Department of National Defence leased the land for use by Royal Roads University.

About 8 nautical miles (15 km) further on, after the ship has steamed past Metchosin’s Albert Head Lighthouse, the Race Rocks Lighthouse appears, warning of the dangerous rocks and the even more dangerous tidal currents “racing” around them. Keeping that light well to starboard (while remaining in Canadian waters, as the border with the United States lies in mid-channel), the Maquinna picks up even more speed, heading into the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Turning northwestward into the strait, which measures between 10 and 15 nautical miles wide (18 to 27 km), the ship and her passengers begin to feel the first effects of the Pacific swells.

At this stage of the journey, first-class passengers are settling into their bunks under crisp, clean sheets and eiderdowns. Second-class passengers in their four-berth cabins are getting to know their fellow cabin mates as they choose their upper or lower bunks. In the lounge, those who have chosen the second-class option but not paid for a berth in a four-bunk cabin stake their claim on the couchettes and nestle in for a fitful sleep. Outside on the deck, First Nations people settle down among their baggage, including blankets, mats, pots, pans and other cooking utensils, and try, as CP inspector H.W. Brodie described in his 1918 report, “to make themselves as comfortable as possible, and, Indian fashion, taking everything as it comes.”35

On the bridge, Captain Gillam keeps a watchful eye as the Maquinna steams at a comfortable 10½ knots past the entrance to Sooke Harbour. If Gillam requires more speed, he can order his engineer to take the ship up to its maximum speed of 13½ knots, but that would only hurt the Canadian Pacific’s bottom line, using too much oil to fire the ship’s boilers. Troup, back in his office in Victoria, constantly reminds his captains of the need to be economical, especially on this west coast run, rated as one of CP’s least profitable routes.

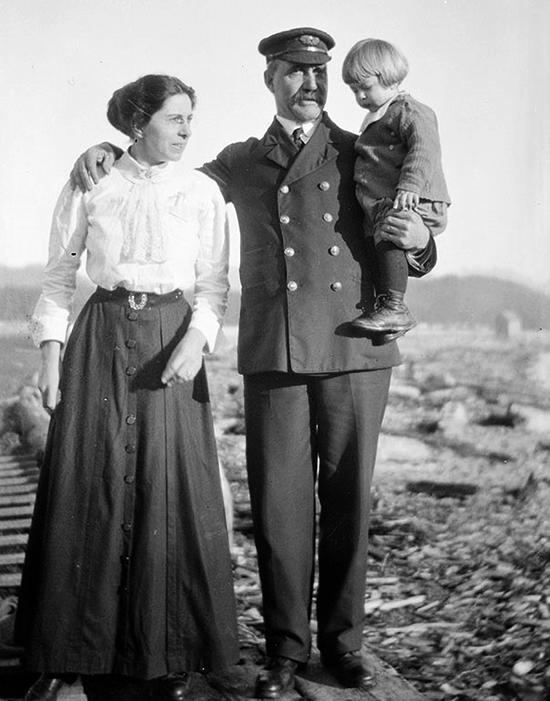

Captain Gillam is a favourite of all who sail on the Maquinna, from crew to passengers. “In a photograph of unknown date, he appears as a robust-looking man with a military bearing, a trim mustache and a kindly expression,” writes Tony Guppy in his book The Tofino Kid:

"He had the far-seeing gaze of a mariner and obviously belonged to that breed of seafarers who were absolutely dedicated to their work. It was well known that every trip he made, no matter how routine, was carefully planned. Every turn of the tide, every eventuality, fog or storm, the time of arrival at every port, would have been judiciously overseen and arranged for the comfort and safety of his passengers. In fact, if necessary, schedules were abandoned in the interests of passenger safety and well-being and stops were missed out altogether if, for example, a passenger was taken sick and needed medical attention. Captain Gillam would stay on the bridge many hours without sleep when conditions were bad, and this would be the usual, rather than the unusual. In the winter and fall months, dense fogs would blow in to blanket the coast, and sudden gale force winds would kick up mighty seas.36

"

On this night calm summer weather prevails, making for smooth sailing. Five hours after departure, at just after 4 a.m., and 57 nautical miles (105 km) out from Victoria, the Maquinna reaches her first stop at Port Renfrew, named after Lord Renfrew who planned on settling Scottish crofters in the area in the 1880s. Situated at the head of San Juan Inlet, and at the mouth of the San Juan and Jordan Rivers, the community originally bore the name Port San Juan, so dubbed by Spanish navigator Manuel Quimper in 1790. This small fishing and logging port, with a population of about one hundred, most employed by the Defiance Packing Company cannery, changed its name to Port Renfrew in 1895, because mail bound for another San Juan in the American San Juan Islands often showed up here by mistake.

Open to the unbroken power of the Pacific, the long pier at Port Renfrew makes for difficult docking, and in stormy weather the Maquinna’s deck crew needs to use six hawsers, or docking lines, to hold her in place, but in calm weather, three holds will do. If heavy swells are running the deck crew is kept busy constantly tending the hawsers and in such weather the loading doors remain closed and all cargo for Port Renfrew must be off-loaded using the ship’s derricks. As soon as the winches and derricks begin clattering and banging, the passengers in their cabins awake with a start and find themselves lying wide awake because of the “unholy row.”37

Between 1901 and 1907, before the Maquinna serviced Port Renfrew, a unique and unlikely group of students and instructors from the American Midwest arrived here on the SSTees and the SSQueen City, the Maquinna’s predecessors. In those six summers, the landlocked Midwesterners, mainly from Minnesota, Ohio and Nebraska, travelled first by rail across the United States to Seattle and then by ship to Victoria before heading up the west coast, to study the sea life and geology of an extraordinary area now known as Botanical Beach, 2.5 miles (4 km) southwest of Port Renfrew. Once disembarked, the groups of thirty or so students, including many young women, hiked through the forest along an “appallingly rough, muddy”38 trail for four hours, packing all their belongings as well as food and supplies to the site they called the Minnesota Seaside Station. There, the students immersed themselves in studying the rich sea life that abounds in the unusually deep tidal pools, hewn out of the sandstone over millennia by the pounding waves.

The dream of biologist Dr. Josephine Tilden, this seaside station provided the students with a rare opportunity to do Pacific Coast field-study work. The students thrived here, even though many had never seen the sea before. “The challenges of fieldwork at the seaside station required the women to plunge into tidal pools, teeter along slippery logs in the dark, slog over muddy trails carrying heavy luggage—some even donned men’s overalls, amid gales of laughter, for the long hikes. They had never been so free, or so far from home, and they loved it.”39

Despite the success of the program and the enthusiasm of the two hundred or so students who came to the Minnesota Seaside Station during the six years it operated, and although Josephine Tilden was using her own funds to support it, the program ended in 1907 because the regents of the University of Minnesota announced that the university “could not own and operate buildings and grounds within the confines of a foreign country,”40 ending one of the many curious and improbable ventures that have flourished and died on the west coast.

Back at the Port Renfrew dock, the clatter of the Princess Maquinna’s winches, and the general racket created by the off-loading and loading of cargo, makes sleep impossible for most passengers. Soon, however, with the ship stopped, a new sound echoes along the passageways outside their cabin doors, as a steward beats out a tune on his xylophone-like chimes shouting out: “First call to breakfast, first call to breakfast!” With that, passengers make their way along the passageways to the dining saloon at the aft end of the main deck to partake of the first of six meals the galley serves each day—two sittings each of breakfast, lunch and dinner. The guests enter the dining room, capable of seating ninety people, to a space fitted with large portholes arranged so that, as far as practical, each table sits opposite a porthole, allowing plentiful natural light to shine into the saloon. Mahogany panelling covers the walls, set with cornices and plaster; the deck is made of Oregon pine, the ceilings panelled with cedar and painted white. The tables lie covered by white damask tablecloths, with silver place settings and gleaming chinaware, including teapots, cream jugs and sugar bowls, all embossed with the insignia of the Canadian Pacific. White-jacketed waiters stand by the tables, an immaculate tea towel folded over their left arms.

Take a seat, and start breakfast with a bowl of stewed prunes—familiarly known as “CPR strawberries” because of their ubiquitous presence on the menus of all CP ships and trains—“as if the railroad company had in mind before anything else the regularity and good digestive health of its passengers.”41 Follow these with a hearty plate of porridge laden with brown sugar and real cream, and afterwards tuck into a plate of fried bacon, eggs and toast, washed down with tea or coffee. Thus fortified, passengers face a leisurely morning’s travel, awaiting the steward’s next gong to bring them back to the dining room to partake of luncheon.

An hour and twenty-five minutes after arriving, with Port Renfrew’s cargo off-loaded and some new passengers welcomed aboard, the Maquinna backs away from the dock and heads northward. In calm summer weather, this next leg of the route makes for sedate and pleasant sailing, but in winter, when storms rage, these waters have proven to be some of the most dangerous and perilous on the west coast of the Americas, claiming hundreds of lives and scores of ships.