Chapter 20: Tributes

Westcoasters in the many outposts served by the Maquinna felt betrayed by the CPR. Some argued that the company had deliberately allowed the ship to deteriorate in order to remove her from service. Most had grown so attached to the Maquinna they found it extremely difficult to acknowledge the changing times and many problems that inevitably led to the ship’s demise.

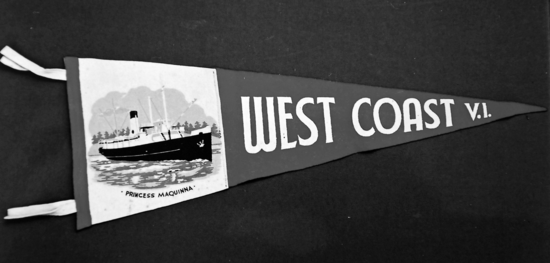

While other Princess ships also held special places in the hearts of those who travelled in BC waters, none held such deep connections to her passengers as the Princess Maquinna. The people living on the west coast of Vancouver Island relied on and loved that vessel, and a special bond had built up for nearly forty years. They became friends with its captains and crew members, treating them as extended family members—the Princess Maquinna was “their” boat. James K. Nesbitt wrote this eulogy to the ship in the Daily Colonist in 1953:

"The Princess Maquinna became an institution along the rugged, splendid West Coast, she poked her nose against rickety docks, and tied up alongside floating logging camps, and often anchored out to unload her freight by tender, or into Indian dugouts. Those who travelled in her will never forget her—the strange zig-zag passageways, the unpretentious, homey lounge, the tiny smoking rooms, the cozy dining saloon with its atmosphere of a kindly home. There were many who could never resist a Maquinna trip each year. They learned to love the vessel, to feel safe in her. Most of them liked to be in her, too, when there was a storm, and they gathered round the warm funnel, as the ship rolled and plunged, the salt sea spray in their faces, the wind whistling in the rigging, the boards groaning and creaking.215

"

When the Princess Maquinna ended her service on the west coast, the chorus of protests swelled, and then gradually faded as the coastal communities adjusted to the new reality. Meanwhile, writers and journalists familiar with the ship outdid themselves writing articles commemorating her.

In her book Personality Ships of British Columbia, Ruth Greene quotes journalist Cecil Maiden’s wry and fond tribute to the Maquinna:

"The Maquinna is an ugly ship. With her thin, elongated funnel and her ill-proportioned bow, she is ugly from any direction in which you look at her. She is also one of the most uncomfortable vessels on which I have ever travelled—with one green-leathered unlovely public room to sit in, and a couple of padded benches along a central space adjoining the purser’s office. But like the Ugly Duckling of the fairy tale, she has stolen the hearts of the people, and I doubt if any vessel afloat could be more beloved.216

"

Greene continues, sharing her own knowledge of the ship:

"And that is just about how the West Coast thinks of her, for she is not just a part of their history; she has made it... At times when no fish boat could fight through the wild seas... always around the headland or behind the driving rain, has been the Maquinna—nearly always on schedule; nearly always with a handful of people coming to build a new home, or her ruminating Indians on their way from the market to their ancestral fish grounds... She has deepened the bonds of family and opened up the solitary places.217

"

Perhaps no one put it better than Dorothy Abraham in her book Lone Cone, a memoir of her years living on Vargas Island and in Tofino:

"There was always excitement on boat days, and everyone went down to see the Princess Maquinna come in and to pick up their stores and mail. They came from up the inlets, from over the mountains, through the forests. They rode horseback or they walked from miles inland. They came in dugouts, row-boats, put-puts and all manner of craft. Indians would paddle out to welcome the Maquinna, wearing gay colours, gracious in their canoes. As she bustled in and out of 26 ports of call, she became a friend to all—their link with civilization. If ever a ship took on body and soul and personality, lived fully, loved by all who sailed in her, it was Princess Maquinna. And there’s a catch in the throats of those who loved her to know that now it’s farewell forever.218

"

In 1958, a few years after the demise of the Princess Maquinna, the CPR sold the Princess Norah to Northland Navigation, which renamed her the Canadian Prince. In 1964 she was stripped of her machinery and towed to Kodiak, Alaska, where she became the Beachcomber restaurant and dance hall. With her sale the CPR ended more than half a century of freight and passenger service to the small coastal communities of Vancouver Island. Robert Turner states in his book Pacific Princesses that: “While the CPR’s retirement from the steamship business had been rapid in the 1950s, in the early 1960s it was precipitous.”219

The last Princess ship, the Princess of Vancouver, entered service in 1955 carrying passengers and automobiles between Vancouver and Nanaimo. However, following an eight-month-long shipping strike in 1958, the BC government purchased the BC routes of the Black Ball Ferry Line, and then created the BC Ferries Corporation. The combined effect of the strike and the creation of BC Ferries served as the death knell for the remaining CPR coastal service, which slowly began to dissipate. In February 1959 the last night boats that had sailed to and from Vancouver and Victoria for decades made their final journeys. The next year the CPR found it could no longer compete with BC Ferries, which ran eight return-trip sailings a day between Tsawwassen and Swartz Bay, leaving the Princess of Vancouver on the Nanaimo route as the sole CPRPrincess ship still sailing on the Pacific coast. Slowly the CPR sold off the old Princess ships, while others in its fleet continued to carry freight and rail cars. On November 17, 1998, however, Seaspan Coastal Intermodal Company bought what remained of the Canadian Pacific’s coastal marine operations, ending an era of shipping in BC waters that had served so many British Columbians so well for over a century.

Though no CPR ships ply BC waters today, those wishing to take a trip like the one travellers took on the Princess Maquinna in 1924 do have some options. They can board the Uchuck III, based in Gold River, on a variety of day trips to Nootka and Zeballos and an overnight trip to Kyuquot; or the Lady Barkley from Port Alberni on day cruises down Alberni Inlet to Bamfield. From Campbell River, the Marine Link’s MVAurora Explorer provides a limited number of passengers a five-day trip north up Seymour Narrows and into the inlets of the Broughton Archipelago. They all perform the same kind of passenger/freight service once carried out by the Maquinna. Those wanting to take a longer sea journey can pay thousands of dollars to travel on foreign-owned cruise ships from Vancouver to Alaska. None, however, can replicate the memorable experience those hypothetical 1924 passengers enjoyed for only $39 for a week-long trip along the west coast of Vancouver Island aboard the Princess Maquinna.

The Belleville Street terminal in Victoria, where the Princess Maquinna once sailed to and from, still serves as a shipping terminal for the Black Ball’s MVCoho, which makes twice-daily voyages across the Strait of Juan de Fuca to Port Angeles on Washington State’s Olympic Peninsula. Few physical reminders of the Princess Maquinna still exist, save for her bell and binnacle, fittingly housed at Tofino and Ucluelet respectively. Her legend still survives in the annals of British Columbia’s maritime history, where the Princess Maquinna is lovingly remembered as the “Best-Loved Boat” that ever sailed the waters of British Columbia.