Chapter Five: Despair and Recovery, 1940–1955

War became a reality in Kelowna when France was invaded in the spring of 1940 and the Battle of Britain began a few months later. The provincial police warned of sabotage and men from the local militia, the BC Dragoons, were dispatched to guard CNR and CPR bridges along the mainline. Extra guards were stationed around the armoury, the packinghouses, the power plant and the ferry when it docked overnight. Each edition of the Courier featured the column “Canada at War—A Review of Developments on the Home Front,” and highlighted the opening of a recruitment centre and the forming of a civil defence unit of the over-thirty-fives and those too vital to the local war effort to leave town. They would be taught to deal with poisonous gas, incendiary bombs and high explosives, and learn basic first aid.

Kelowna had to be prepared, though air raids were unlikely. A long steady blast from the hand-cranked fire siren would let everyone in town know if enemy planes were approaching. Police cars would drive up and down country roads with their sirens blaring to warn those in rural areas. The alarms could be sounded any time of day or night but a night raid would be confirmed if the street lights had also been turned out. All windows and doors had to be blacked out at dusk and covered with heavy paper or blankets. If driving was absolutely essential, headlights had to be covered except for a three-inch-long vertical strip, a quarter of an inch wide. A pail, a shovel and a garden hose had to be kept at the ready to deal with the inevitable fires from incendiary bombs. The two-pound, highly inflammable magnesium tube bombs were filled with a mixture of powdered aluminum and iron oxide that would ignite fiercely hot blazes all over town. The fire department couldn’t be expected to attend every fire and citizens had to be prepared to look after their own property.

War was costly and while higher taxes paid a portion, the public was expected to pay the balance by purchasing Victory Bonds and war savings certificates. A series of extraordinary campaigns between June 1941 and October 1945 raised billions of dollars for the war effort from ordinary Canadians. Communities and salesmen had quotas and each town had a “special names” list of those identified as substantial purchasers. The Courier ensured everyone knew their patriot duty and then celebrated when Kelowna was the first valley community to reach, and then exceed, its quota. Everyone, including children, was urged to buy “ribbons of silver,” the twenty-five-cent stamps that could be bought at the grocery stores and fixed to a savings certificate until they totalled five dollars.

Fundraising campaigns were constant: the Red Cross asked for money for soldiers overseas and their families at home; a donation of one dollar would provide Prisoner of War Parcels for Allied soldiers; the “Bury Hitler Under Aluminum” campaign urged people to bring their old pots, pans, kettles and percolators to be melted down and turned into airplane parts so Berlin could be bombed more frequently by ever more planes. When the Nazi campaign targeted Russia, funds were raised for the starving and destitute in that country. When the Japanese invaded China, money was raised to help the Chinese. The Courier, likely thinking this was a short-term commitment, turned its advertising revenue from government ads into war savings certificates: loyalty to the British Empire was paramount and everyone and every business was expected to pitch in to do their duty.

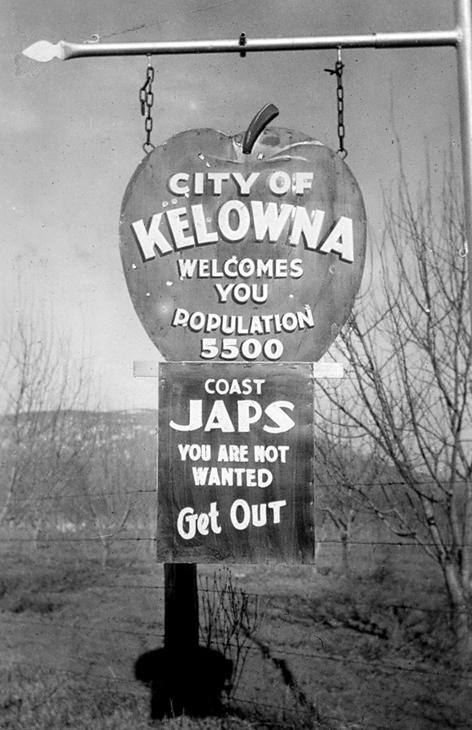

People’s anxiety levels escalated dramatically after the December 7, 1941, Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The Courier stated that “the people of British Columbia are realizing as they never have before that we are fighting for our very lives… we are in the midst of a final fight for our home, lives, and way of life.” With this one act, those who had looked at the early civil defence plans with “tolerant amusement” suddenly realized war was on their very doorstep. A delegation of local Japanese residents appeared before Kelowna City Council less than a week after Pearl Harbor, with a statement: “We, the undersigned Japanese residents of Kelowna and vicinity, wish to express our deep regret at the state of war existing between Canada and Japan and each of us pledges herewith to be a loyal and good citizen of Canada. In presenting this pledge to the authorities of the City we shall be grateful if you and your fellow citizens accept our fidelity and understand our sincere attitude in the awkward position in which we find ourselves.” The acting mayor assured the delegation he had every confidence that the Japanese would receive the benefit of the usual British justice and sense of fair play in the future, just as they had in the past.

The 130 men who appeared before council represented about 332 Japanese who were living in the area, half of whom were born in Canada or had become naturalized citizens. The Okanagan was home to the greatest number of people of Japanese descent beyond the west coast, and many had lived in the area for over twenty-five years. A hundred-mile exclusion zone had been established along the Pacific Ocean and all Japanese men between the ages of eighteen and forty-five were deemed a security risk and removed to internment camps in the BC Interior, the Prairies and Ontario. It wasn’t long before their wives and children were also removed and interned, often in different camps than their husbands and fathers. Though the local Japanese residents remained in their homes, their world changed: they had to register with the RCMP, they couldn’t travel, they had to surrender any firearms and they had to face friends who turned away and the shopkeepers who no longer welcomed their business. Those who tried to enlist were rejected.

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, the Kelowna Courier suggested that Japanese residents should be left alone and shown a little sympathy. However, as the “Pearl Harbor Japs” from the coast were rounded up and moved to internment camps in the Interior, the Courier and many others changed their minds. The city and its newspaper became known for virulent and hateful statements against any Japanese people who came into the area, for whatever reason. Vitriolic headlines were commonplace and large signs proclaiming “No to Coastal Japs” appeared in store windows and nailed to rural fence posts. When it was impossible to find workers for the orchards and vegetable farms and the BC Fruit Growers’ Association (BCFGA) proposed using Japanese internees, city council reluctantly agreed but only if the province guaranteed they would all leave the area once the season was over. When local Japanese farmers arranged for internees to work with them, alarm was raised in case the internees remained in Kelowna for the duration of the war… or worse, after the war. School districts didn’t want to pay for internee children to go to school, curfews were strictly enforced and shopping was only allowed on Mondays—and even then, only under the watchful eye of the RCMP.

Though not everyone in town was caught up in the hysteria and paranoia, the majority claimed it was an appropriate response in times of war. Kelowna’s British colonial and racist roots were showing. Even when the war was over, the Courier reported that when a young Indo-Canadian woman tried to buy a house near a downtown school, neighbours and several prominent organizations signed petitions to stop the sale from going through. “If Orientals settle in the neighbourhood, it would be a starting signal for more Far Eastern natives to move into the residential district, with the result that the area would slowly grow into a Hindu settlement, thereby lowering property values and causing general unpleasantness.” In spite of the obstacles and city council’s announcement that “we have a town composed of Anglo-Saxons and it should continue so,” the young lady persisted and the neighbourhood survived.

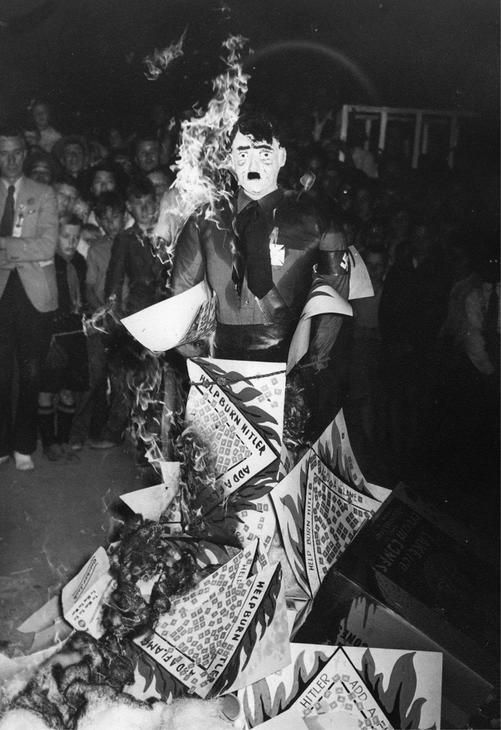

Kelowna celebrated the end of the European war in the first week of May 1945. Shops and schools closed as flags and bunting appeared on Bernard Avenue and five thousand gathered in City Park for a Thanksgiving service. Bands played, home guard units marched, Boy Scouts and Legion members sang “Onward Christian Soldiers” and everyone celebrated the “Empire’s victory.” And after atomic bombs decimated Hiroshima and Nagasaki a few months later, the Courier noted that a “joyous but orderly crowd” celebrated Japan’s capitulation. With the war over on both fronts, “all Kelowna and his wife and family gathered on Bernard Avenue in the evening and were joined by most of the people in the rural areas.” Thousands danced on the street in front of the Royal Anne Hotel as many more watched from the sidelines. Fire sirens were joined by factory whistles and car horns and stores were raided for toilet paper that was turned into streamers for the cars, trucks and bicycles parading up and down the streets. CKOV was on Bernard Avenue with a live broadcast, Chinese residents flew the Chinese flag, armoured vehicles and anti-tank guns were towed, and a flaming gold torch, saved from an early Victory Loan campaign, was symbolically extinguished. Staid Kelowna let loose and celebrated.

The Kelowna and District War Veterans Rehabilitation Committee helped those returning from the war find housing and jobs. The “Women’s Problems” subcommittee held teas at the Willow Inn to introduce war brides to Canadian ways. Housing became a major issue and the city offered one hundred lots to Wartime Housing Ltd. for one dollar: two-, three- and four-bedroom houses could be built on a cement pad for about $3,800. Each would be of the latest design with clothes closets, electrical fixtures, indoor bathrooms and a circulating heater. A woodshed was attached for the wood or sawdust that would be used for cooking and heating.

So few building materials had been available during the war that citizens had been encouraged to make do or renovate. Shortages continued even after the war and veterans were given purchasing priority ahead of the general public. As the demand for housing vastly outstripped the supply, even furniture dealers had trouble locating supplies and stoves were almost impossible to find. Since plumbing fixtures could not be produced fast enough to keep up with the countrywide demand, both servicemen and newcomers began building shacks and outside privies on city-owned land.

Wartime houses appeared in Kelowna’s north end and near its southern boundary. In keeping with the empire’s tradition of rewarding service with land, the government created the Veterans’ Land Act (VLA) and bought seventy-five acres from Bankhead Orchards. About thirty houses were built and made available to deserving and needy veterans whose names had been pulled from a hat. Some veterans took advantage of low-interest loans, bought the rest of the land and built their own houses. The VLA hired other veterans to travel the valley giving assistance to new growers, many of whom had bought large acreages in spite of not having any orchard experience.

A Suitable Memorial

Kelowna looked for a way to pay tribute and give thanks to both those who served in World War II and those who died during the conflict. Communities across the country were talking of statues and plaques but the idea of a “living memorial,” something that would be more useful to citizens, began catching on. Kelowna had struggled with high delinquency rates during the war, and that had been blamed on the departure of most of the community’s positive role models and leaders. The young had been left without guidance, had nothing to do and got into trouble with the law as a result. When an ice arena was suggested as a memorial, with a legacy of “developing harmony and happiness for future generations,” everyone agreed and began searching for an appropriate site.

The Kelowna Saw Mill, adjacent to the downtown business district, had been sold in 1942 by its early owner, David Lloyd-Jones, to Stanley M. Simpson, owner of the other sawmill in town. Fire destroyed many of the buildings two years later and rather than rebuild, Simpson moved its production to his Manhattan Beach operation. When approached by city council in 1944 and asked if he would sell the property to the city for a future civic centre, Simpson agreed, though he insisted on certain conditions. Discussions were initially about the seven and a half inland acres but they soon expanded to include the four and a half acres adjacent to the lake. Citizens approved of the purchase of both parcels by referendum and council agreed to the covenant that Simpson placed on the land. The agreement stated that the land would only be used for civic purposes, that it could never be used for commercial or industrial ventures and that it could never be sold. It was also to be pleasantly landscaped and developed for the use and enjoyment of the citizens of Kelowna. The cost of the land was equal to the amount Simpson paid to have the fire debris and years of sawmill residue cleared from the land: $55,000. The price was substantially below the market value of comparable commercial properties in the area.

It didn’t take long for the War Memorial Committee to decide the new civic property was the perfect location for their arena and set about raising funds to pay for the building. It wasn’t an easy task, but the first $100,000 of donations and pledges were in hand by January 1, 1946. All available lumber, building supplies and labour were being used to build houses for returning soldiers by that time, so council delayed the project for eighteen months. Costs rose and there was a shortfall of $75,000. Voters approved the increased expenditure by referendum, though some thought council should have been more diligent in calculating the costs. By the fall of 1947, council again asked voters to approve a bylaw for an additional $80,000: this time a few donors asked for refunds. When a further $45,000 was needed, the committee began eliminating some amenities. The 1948 floods caused even more delays when the lake inundated the recently laid foundation. By October that same year, taxpayers were being asked to put up another $50,000 and council was being roundly criticized. Then an arsonist began setting fires and the derelict planing mill directly behind the arena went up in flames. Fire crews let it burn and turned their hoses on the partially finished new building.

The arena’s official opening was a sombre event as veterans of both wars marched from the cenotaph to the Memorial Arena on Remembrance Day, November 11, 1948. The invocation called for all to play with generosity, lose gracefully without rancour and be worthy of those in whose memory the arena had been built. The town’s first artificial ice rink quickly became the community’s winter focal point and home of the Kelowna Packers, the city’s Okanagan Mainline senior amateur hockey team. When Barbara Ann Scott, the Olympic figure-skating champion, came to town as part of the 1949 Ice Frolic, Kelowna “welcomed the world’s finest figure skater with all their hearts.” The city fathers were apparently so astounded she would perform in Kelowna they bestowed the Freedom of the City on her. A great variety of summer events took over when the ice was removed: wrestling and boxing matches, craft shows, the Royal Lipizzaner Stallions, circuses, symphonies, roller derbies and high school graduations, among others happenings. With seating for two thousand, it was the largest venue in Kelowna for many years.

Commando Bay

Commando Bay isn’t in Kelowna, but neither is it very far away, and it was the site of a little-known operation that holds a unique place in Canadian military history. Originally named Dunrobin’s Bay after its first pre-emptor, the small bay was renamed after World War II because of the secret activities that took place on its isolated beach and dry upland benches. Commando Bay is now within the boundaries of Okanagan Mountain Park.

As the war in Europe wound down, battles in the South Pacific were intensifying. Deep within the British War Cabinet, an organization known as the Special Operations Executive (SOE) was responsible for training commandos to work behind enemy lines. Most of its operatives were European, and as such were unsuitable for deployment to the Far East. They needed to find Chinese recruits and looked to the British colonies, specifically Canada, for them.

In 1944, a call went out for volunteers. Though many first-generation Chinese men had tried to enlist during the war, few had been selected. The Chinese had been denied voting rights since the late 1800s and many felt enlisting would improve their chance to rectify the injustice. The government in Ottawa thought so too, however, and didn’t want to open the door to the possibility. From the twenty-five who volunteered, thirteen were selected for what became known as Operation Oblivion.

There were no roads to Commando Bay, which was chosen because of its isolation and inaccessibility. Supplies and equipment were dropped off at a wharf that had just been built, tents were set up about three hundred yards up the hill above the beach, a cookhouse was added and everyone settled in for the next four months. Recruits were trained in small arms, explosives, sabotage operations, demolition, unarmed combat, and ambush planning and execution. Survival techniques, wireless operation and radio telegraphy were important as well, as part of the mission’s goal was to stay in contact from behind enemy lines. The young men worked from dawn to dusk with their only break coming when the commanding officer learned that the Paradise Ranch, their closest neighbour, couldn’t find people to pick their peaches and the recruits spent a couple of days helping out.

Demolition training was carried out on the hill above the beach. As their expertise grew, the crew moved along to the mouth of Wild Horse Canyon where they found an abandoned cabin to store their supplies. Was it the cabin left by the Naramata Road building crew? It was originally expected that the recruits would know the Chinese language: most didn’t. As often happened with immigrant parents who wanted to ensure their children’s success in a new world, most only spoke English. Chinese language instruction was added to the training.

The recruits trained and toughened up during the four intense months, and when it was time to leave they packed up their tents, scoured the area to make sure no live ammunition had been left and departed. Other than the wharf, which soon deteriorated, there were no signs that anyone had ever been at the site. The group returned to Vancouver, went up the coast for underwater training and then headed to Australia for parachute training. Dropped behind enemy lines in Borneo, the men collaborated with local head-hunting tribes and succeeded in driving the Japanese from the area in less than two months. The atomic bombs were dropped not long after, and the Japanese surrendered.

There are no written records of Operation Oblivion. Most of the stories about the secret unit have been lost to time, though a recent video prepared by a daughter of one of the survivors has captured some memories. A reunion of those trained at Commando Bay was held in September 1988: ten of the thirteen soldiers revisited their training site. Among them were businessmen, an aeronautical engineer, a lawyer and an MP. A plaque and some poppy seeds that were scattered along the beach by one of the departing veterans were all that remained of their visit. Chinese Canadians were granted the vote in 1947.

Too Much Water

Much of Kelowna was built on the flood plain adjacent to Mill and Mission Creeks and Okanagan Lake, and residents learned to live with the often annual reality of high water. Basement pumps were essential for everyone living near any water and when they couldn’t keep up with rising levels, live fish settled in for the duration, inches of tadpoles carpeted low-lying fields, mosquitoes were fierce and filling sandbags became an annual rite of spring.

Kelowna was inundated with water every few years, but 1948 was the worst. Relentless rains were compounded by heavy mountain snowpacks and the Okanagan watershed could not contain the runoff when the hot weather arrived. The Fraser River was also in flood and rail, telegraph and telephone lines to the coast were cut. Gasoline couldn’t be delivered and had to be rationed for all but essential vehicles; food supplies ran low and officials pleaded with residents not to hoard. Hundreds of railway passengers were stranded in Kamloops when westbound rail lines disappeared under water. The southbound rail line was fortunately still in service, and passengers were diverted to Kelowna, where they were greeted by Red Cross volunteers and given coffee and sandwiches until buses could be arranged to take them to Penticton. Though parts of that road were also under water, they got through to the Penticton airport where Canadian Pacific Airlines and Trans-Canada Airlines became part of the rescue mission. More than 1,200 passengers were flown to Vancouver over a two-day period.

A province-wide plea for funds to help flood victims in the Fraser Valley must have seemed a bit unfair to those in Kelowna struggling with their own catastrophe. Creeks overflowed their banks and flooded acres of low-lying hay and vegetable fields, bridges were washed out and houses alongside the rampaging creeks were bulldozed out of the way instead of being left to collapse into the stream. Some roads were under two feet of water, and everyone gathered to fill sandbags in a sometimes futile effort to keep the rising water out of their homes. City Park was under water and the lower bleachers of the Regatta grandstand were submerged. The city threatened to cut off residents from the already overwhelmed sewage treatment system and told those on septic tanks not to use them: communal outhouses were set up on drier ground. Drinking water had to be boiled, typhoid shots were free to anyone who wanted them and swimming in the lake was forbidden. As lake levels rose, water backed up even farther into creeks and backyards, and gardens five and six blocks from the lake were under two feet of water.

These were also the peak production weeks for making wooden fruit boxes and 1948 was shaping up to be a record crop. S.M. Simpson Ltd., the valley’s main box manufacturer, was running seventeen hours a day and producing about eighteen thousand apple boxes during the two shifts. The veneer plant and sawmill were also working at full capacity: closing the plant wasn’t an option as no boxes and the loss of five hundred jobs would be a further blow to the community. The sawmill had originally been built on low-lying land but with repeated layers of sawdust and slabs overlaid with loads of gravel the site had been built up over time. High water levels created another challenge, however, as the mill’s five boilers were close to being submerged. Makeshift wooden dykes were built and managed to hold back two and a half feet of water though pumps still ran twenty-four hours a day to deal with the seepage. Electric motors, many operated by leather belts, had to be raised on wooden blocks as the men sloshed through floating debris in their high rubber boots.

It took Kelowna many weeks to dry out. Municipal authorities blamed provincial and federal governments for not acting on a 1946 engineer’s report that highlighted the urgent need for improved flood control. The Honourable C. D. Howe said works of this type were best left for the next Depression. By 1954, though, a flood-control project created a channel between Okanagan and Skaha Lakes and then straightened the meandering river between Skaha and Osoyoos Lakes. The catastrophic floods of 1948 would never recur.

A Good Time for Orchardists

Okanagan orchardists flourished during the war. Currency restrictions plus embargoes on bananas, citrus fruits and foreign apples all resulted in a strong Canadian demand for valley produce. Customers were so happy to have any fruit they bought what was available in spite of high prices and questionable quality—growers had decided to maximize production by applying enormous amounts of fertilizer, though it was known to reduce the grade and storage capacity of their apples.

More people moved to town after the war, and more land was needed for residential development. Level farmland was seen as the best land to build on even though it was also the most productive and easiest to irrigate. Alternatives had to be found. Valley hillsides had always been difficult to irrigate but when aluminum became available after the war and was found to be both malleable and corrosion resistant, it provided the solution. Soon electric pumps and more efficient sprinkler heads were added to the new aluminum technology and the hillside acres of sandy loam were transformed into productive orchards. Many of the early orchards were torn out and replaced with houses, though an occasional apple or cherry tree was often left behind in the yard. As land prices rose, many acres of grazing lands and hay farms were no longer viable and they too were transformed into subdivisions.

When the war ended, so did the protection apple growers had enjoyed during the hostilities, and they were overwhelmed by the tons of culls they were still producing. There were few options other than letting the apples rot, either on the trees or mounded on empty lots or in country ravines. Currency restrictions remained in place in Britain and Okanagan orchardists couldn’t access their traditional market. The decision was made to “gift” 1.1 million boxes of apples to Britain to avoid dumping them or overwhelming the Canadian market. The British government hadn’t bought apples for three years, and even then it had only been a meagre 434,000 boxes. BC Tree Fruits paid the freight charges to the coast, the shipment went through the Panama Canal and the gift of small-sized McIntosh, Newtowns, Romes, Staymans and Jonathans rescued both the Okanagan growers and the fruit-starved British. Not all growers agreed with BC Tree Fruits’ generosity but when the federal government later came through with a $2 million subsidy, the disgruntled stopped complaining.

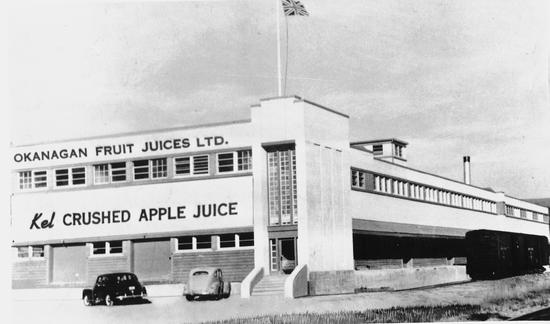

There had been earlier attempts to use the culls for vinegar, dehydration and apple juice, though the amounts produced were insignificant. The Okanagan Fruit Juice Company began making a new cloudy (opalescent) apple juice in the Rowcliffe Cannery and this became so successful they decided to build their own state-of-the-art production facility. With local backing and additional technical and financial support from the Hawaiian Dole pineapple family, production got underway in 1946. Their timing couldn’t have been worse. Apple growers, through the BCFGA, had just decided to form BC Fruit Processors Ltd. and get into the apple by-products business to help them deal with the overabundance of culls. Since this new company would have first call on the culls as well as the area’s McIntosh crop, Okanagan Fruit Juice realized they couldn’t compete and sold their facility to the new growers’ company.

It was a slow start—the first year they produced 373,000 cases of apple juice and made concentrate for apple butter, vinegar and dehydrated apples, but still only used a small portion of the culls. Business improved with the new modern facility and the company decided to absorb most of the juicing operations from around the valley into the Kelowna plant. The exception was Oliver, where apple juice had first been produced. That operation continued for a few more years until it made better economic sense to use tanker trucks to bring the juice to Kelowna for processing. BC Fruit Processors’ brand, Sun-Rype, soon became a familiar name on store shelves.

The canneries, which had been such an important part of the fruit industry, also began to close. Frozen food was gaining in popularity and the nutritional benefits of fresh produce were also being recognized, so the market for canned foods was diminishing. That left peach, cherry and apricot growers with few options beyond the fresh market and they too approached the BCFGA to develop products to utilize their crops. Sun-Rype and the Dominion Experimental Farm in Summerland soon developed pie fillings—apple and cherry were the most popular—along with apple sauce, apple dessert, apricot juice and concentrate, and apple-cot and orange-cot juices.

Always looking for more opportunities to utilize their culls, BC Fruit Processors made the precarious leap into fruit-based alcoholic beverages. With only Growers Wine in Victoria and Calona Wines locally, there wasn’t a lot of competition. The Summerland Experimental Farm would ferment a few hundred gallons of apple juice and add pieces of dry ice, by hand, to the get the necessary carbonation. The bottles would then be filled and rushed to the Kelowna liquor store. Provincial liquor laws didn’t allow for alcohol advertising or any promotion of alcoholic beverages, but that didn’t matter during the Regatta. At any and every opportunity the Regatta announcer “just happened” to mention that a new batch of the wonderful new Okanagan Sparkling Cider was arriving at the local liquor store as he spoke. It didn’t take long before the cider was flying off the shelves. However, the company was a bit conflicted about producing alcohol along with its juice and food products and soon sold its inventory and the rights to BC Sparkling Cider to Victoria-based Growers Wine Company.

Other Than Orchards

The war years were also peak production years for S.M. Simpson Ltd. The arsonist’s fire that had destroyed much of the plant in 1939 enabled Stan Simpson to order the latest machinery just before war was declared. None would have been available a few months later, though sawmills were essential wartime industries and given mandatory production quotas to support Canada’s war effort. Women took on various unconventional jobs as men joined the armed forces, but it was with the understanding that the men would return to their old jobs when the war was over. While sawmill production was an essential service, logging was not, and when the loggers left for war, many sawmills ran short of logs. Mill owners tried to convince the government to use Japanese internees in the woods but they were deemed too great a security risk and permission was denied.

S.M. Simpson Ltd. was dealing with increasing demands from both the local orchard industry and the British Box Board Agency, which ordered “butter boxes” (though their actual use and final destination were classified secrets). One shipment of Simpson boxes was torpedoed in the North Atlantic and the mill received a cable asking them to replace it immediately. Dynamite boxes were built for Canadian Industries Ltd. (CIL) on Vancouver Island and a never-ending line of railcars pulled into the siding beside the box factory. Shook was loaded around the clock before the cars headed to Vancouver and on to the Panama Canal. Dimension lumber was also shipped but the need was so great and so urgent that it often left before it could be dried. The green lumber warped and bent but was still used for army barracks, munitions factories and hangars; orders sometimes read, “Send everything you’ve got.”

The number of new fruit boxes needed each year was determined in the spring when the blossoms set, and box factories planned their production accordingly. When the packinghouses determined they would need 900,000 new boxes for the 1943 crop and the box factory was already working at capacity, the fruit industry began exploring other options. They tried packing apples in paper bags but there was too much bruising and consumers were unhappy. Then it was a mix of corrugated fibre and wood and Simpson’s mill provided wooden ends that were wrapped with the heavy paper. It was definitely a temporary solution. The next effort was a corrugated cardboard box but it wasn’t rigid enough to be stacked, so the mill had to produce millions of small triangular pieces of wood that would be inserted into each corner of the box so it could be stacked. It too was a temporary fix and much cheaper than the all-wooden boxes. Not all consumers liked the new containers but it was wartime, and everyone had to make sacrifices. Box makers were relieved that an alternative had been found and they could continue their wartime production. They were also certain that business would return to pre-war levels once hostilities had ceased, and were not concerned that the change might signal a different way of doing things in the future.

Arriving and Departing

By Road

The completion of the Hope–Princeton Highway in fall of 1949 was the fulfillment of a hundred-year dream. Criss-crossing the historic fur brigade trails, it was the largest highway project ever undertaken by the province. The new route reduced the distance between Kelowna and Vancouver by one hundred miles and several hours of travel. Though many would have been happy to have it open earlier, unpaved, the decision to complete the eighty-three-mile link between Hope and Princeton as a paved all-weather road was soon welcomed by all.

Accompanied across the “hallowed ground” by a pioneer who had been in the area for fifty-four years, Premier Byron Johnson turned a golden key in the lock and swung open an improvised gate across the 4,200-foot Allison Summit, the new highway’s highest elevation. The grand and much anticipated celebration attracted over six thousand of the area’s important and curious. Since lunch had been planned for two thousand, the traffic backed up, bumper to bumper, for four or five miles in both directions; some waited over three hours for a police escort to the summit, while the impatient abandoned their cars and buses and walked. Most had not anticipated the elevation and arrived exhausted.

The Hope–Princeton also meant a new kind of highway driving was needed, and people were cautioned to obey the posted speed limits: some of the curves were banked for specific speeds and motorists who ignored the warning signs were “asking for trouble.” The warnings were underscored when three people were killed returning home from the ceremony. Over the next few days, mangled radiators and bent fenders reminded drivers that this was no speedway, especially when they encountered heavy frost in the shaded gorges along the “tricky” highway.

The building of the Hope–Princeton Highway was one of the signature events that opened the Okanagan Valley to the rest of the world. Penticton was the first major town encountered by travellers coming from the coast, and by 1951 it had become the valley’s largest with a population of 10,517 (1941: 5,777). Kelowna, with its boundaries still constrained, grew to 8,466 (1941: 5,118) while Vernon remained the smallest at 7,778 people (1941: 5,209). Those who can still recall those times remember Penticton, with its beautiful beaches on both Okanagan and Skaha Lakes, being everyone’s choice as the valley’s best summer party town.

By Water

The Queen of Okanagan Lake took her last trip down the lake in August of 1951. The Courier reported that noon-hour crowds had quietly lined Kelowna’s beaches to watch as the SS Sicamous passed by. A solitary red-and-white checkered CPR flag “fluttered bravely from the forward mast” while the Pendozi, Lequime and Lloyd-Jones diverted from their regular route to circle the “old lady” and sound their whistles in tribute. Cars on shore tooted their farewell and the fire hall bell rang out in respect. The old sternwheeler was being towed from her mooring at Okanagan Landing, where she had been waiting out her uncertain future for twenty years. The Sicamous’s top deck had been removed and the sternwheeler had spent its last two years of service carrying freight. It hadn’t been a worthy ending for so fine a vessel. The CPR offered the Sicamous to both Kelowna and Penticton. Kelowna declined but Penticton finally paid the CPR one dollar for the “tired but proud old lady” in 1949. It was another two years before the now-decrepit vessel was towed to the beachfront on Okanagan Lake. More recently, a dedicated group of volunteers has restored the still-beached Sicamous, which is now available for rent, though its financial situation is always precarious. It is part of the Penticton Marine Heritage Park, along with the tug SS Naramata.

By Air

Penticton was not only the largest city in the valley, but the first to have its own runway and airport. The facility was opened for emergency military use in 1941, but it wasn’t until 1947 that Canadian Pacific Airlines (CPA) inaugurated the first scheduled service between Vancouver and Calgary via Penticton, Castlegar and Cranbrook. Kelowna residents who wanted to fly out of the valley drove to Penticton to catch a plane. Scheduled flights to the Rutland airfield had been discussed but plans were put on hold during World War II.

Kelowna took the initiative when the war ended and purchased the 320-acre Dickson Ranch in Ellison to be the future site of its airport. It cost the taxpayers twenty thousand dollars. The “Ellison Field” officially opened in August 1949. Many of the 3,500 cars and 10,000 people planning to watch the mayor buzz the airport before cutting the inevitable silk ribbon were stuck in a nine-mile-long traffic jam and never made it to the field. The highlight of the day for those who did arrive was the opportunity to see one of CPA’s “heavy” planes land on the grass runway—it was a “tribute to the Kelowna airport” flight. Although hopes were raised, CPA didn’t start scheduled service into Kelowna for another ten years.

Lobbying for and establishing the Kelowna Airport had been a giant leap of faith. Commercial air travel was in its infancy and very few people had their own planes, and for a few years the Ellison Field risked closure because so little was going on. As planes came and went out of Penticton, L & M Air Service of Vernon flew its first intercity flight in September 1949 to connect Kamloops, Vernon and Kelowna with CPA’s scheduled service in Penticton. The daily (except Sundays) flights were aboard a sleek twin-engine plane, an amphibious six-passenger Beechcraft, which landed on the lake at the foot of Bernard Avenue, and dropped off and picked up passengers at L & M’s new wharf. The plane would land at Ellison Field during the winter with taxi service provided so passengers could travel the considerable distance to downtown. This was “red letter service,” as Vancouver was now only two and a half hours from Kelowna, Toronto was nine hours away, and it only took thirty hours to travel to England. But despite how grand the dream was, it didn’t work in reality, and the service was soon cancelled.

Traffic into and out of Kelowna’s airport was so light that there was a constant risk of it being abandoned and swallowed up by spreading housing developments. A reprieve arrived in 1951 when Ralph Hermanson brought his Cariboo Air Charter to town and offered charter flights and student instruction. Many local residents learned to fly, with some even buying their own planes, and Mr. Hermanson became the airport manager and a strong advocate for both scheduled service and a paved runway.

Canada’s Greatest Water Show

Kelowna’s wartime Regattas took on a distinctly patriotic flavour as all profits were sent to the federal treasury to help fight the war. Military themes persisted: the “Victory Regatta,” the “On to Victory Regatta,” the “Let’s Finish It Regatta.” Various major-generals were also invited to become the Regatta’s honorary commodores. The “On to Victory” Regatta of 1941 invited a team of American majorettes to lead the parade. The Battle of Britain was fresh in everyone’s minds and with the US still on the war’s sidelines, the empire took precedence. When the young ladies were replaced by a reserve military unit and bumped to the back of the parade, they were so mad they packed up, got on the ferry and headed home. In a huff.

The “Liberty” Regatta in 1943 provided the most spectacular evening program ever staged: a commando attack on a “Nazi” beachhead. Spectators had to be in their seats before shooting began so the local militia could secure the area and no one would get hurt or interfere with the battle. Outside of motion pictures, the locals had never seen anything like it. The attack started shortly after eight o’clock just south of Ogopogo Stadium, the bleachers overlooking the swimming pool. The beach’s defence posts were manned by “Nazi” units that had been softened up by “heavy shelling.” Under a screen of smoke laid down by “mortar fire,” the “invading forces” stormed the beach and captured the pill boxes being defended by the “enemy.” Band concerts and acrobats completed the night’s entertainment. They were likely anticlimactic.

By the end of the war, rhythmic swimming had become popular and was introduced to Regatta audiences during an evening show. The performance had unfortunately been scheduled so late in the program that it was dark and spectators were left baffled about what the three young ladies were doing in the pool. Things improved the following year when a larger team from Vancouver and Victoria put on a display of “the highest type of swimming that requires much practice and an accurate sense of timing on the part of all participants.” Everyone could fortunately see this time, and they were in awe at the intricacies of the water ballet. It wasn’t long before Margaret Hutton, a 1934 British Empire Games Canadian backstroke champion, arrived in town to teach ornamental swimming to the area’s young ladies. This was quite a coup for the Regatta as Margaret had moved from competitive swimming to Hollywood, where she had choreographed a water ballet for the movie Pagan Love Song. She had also taught film stars Esther Williams and Eleanor Holm how to perform. Her rhythmic swimming productions—with their specially designed lighting, paddleboards and swimming costumes—became the centrepiece of the Regatta’s elaborate evening programs.

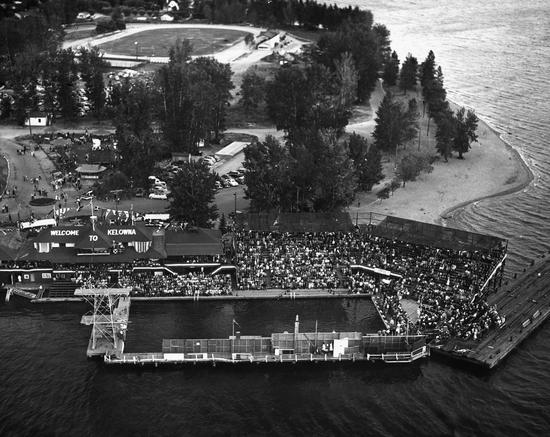

The Kelowna International Regatta grew into a five-day celebration. Junior boys and girls and senior men and ladies came from Vancouver, Victoria and Ocean Falls, up the coast, as well as from Washington and California, to compete in freestyle, backstroke and breaststroke events and medley relays. War canoes raced while three-metre diving competitions were interspersed with boats racing with their “pepped up” motors. A new ballroom, dining room, lounge and grandstand were built. A diving plank was added to the wooden diving tower in 1945 to allow Dr. George Athans—the British Empire Games springboard diving champion who had come to Kelowna to practise medicine—to perform at his best, though it was noted that few would actually dive from that extraordinary height. The board was replaced with a steel Olympic standard ten-metre diving tower in 1951 when there were few others like it in North America, and it was named after Dr. Athans. Though terrified, every kid in town clambered up the ladders and launched themselves into space: it became a summer right of passage. Athans convinced his friend, Dr. Sammy Lee from San Francisco, the Olympic high tower diving champion, to join him for an exhibition in 1953. The crowd was awestruck.

Being “midway” between Seattle and Detroit, the Kelowna Regatta was on the World’s Fastest Power Boat circuit. The tour’s hydroplanes—Slo-Mo-Shun IV and V, Miss Seattle, Miss Fury and Breathless—thrilled thousands of spectators, including those attending the International Regatta, at speeds of up to two hundred miles per hour. The curious could wander the pits along Hot Sands Beach and watch the races throughout the day.

These were the legendary glory days of the Kelowna International Regatta. Athletes came to compete and everyone else came to party. The Bank of Montreal hosted an elegant garden party at Hochelaga, the home of their local manager; the Lieutenant Governor declared a temporary Government House on the lakeshore in Okanagan Mission and hosted the most prestigious garden party ever held in Kelowna. Boaters partied at the Kelowna Yacht Club, visiting military brass were entertained at the armoury and other noteworthy out-of-towners were hosted for morning coffee and a fashion show. Teen Town had a wiener roast at the beach and, at a time when it truly mattered, the Lady of the Lake hosted visiting beauty queens and their princesses from throughout the province and Washington state. Private railcars were shunted onto sidings in the north end so visiting CN and CP vice-presidents could entertain visitors during the event. The Kelowna Little Theatre involved the whole community in staging ever grander evening programs, while visiting bands began playing early in the morning and would continue well into the evening. The Lady of the Lake Ball was held at the much-decorated Memorial Arena, though it was only one of many dances going on around town. When about eight thousand people lived in Kelowna, it was not uncommon for one hundred thousand visitors to arrive in town to celebrate and party during the four- or five-day Regatta.

The whole of Kelowna gravitated to the Kelowna Aquatic Club in the summer. Lifeguards taught swimming lessons along Cold Sands Beach (the beach facing north, which has since been washed away) and the full sun of Hot Sands Beach attracted the bikini-clad sun seekers. Kids had to be able to swim fifty yards, unaided and without stopping, before they were allowed on the dock and in the big pool. They came with their friends, stayed for the day, brought their own lunch or bought fish and chips, and finally drifted home late in the afternoon. Parents knew their children had gone to the Aquatic, where lifeguards would keep an eye on them, and didn’t worry. They knew their kids would head home when they were tired and then likely do it all over again the next day. Kelowna was a great place to grow up in.

The International Regatta was followed by the Junior Regatta, in which locals competed and the Man of the Lake was chosen. Though he had few perks and no official functions, the event gave the young men who had spent the summer racing shells and war canoes a chance for a moment in the limelight. Locals also competed every Tuesday night during July and August in the Aquacades, or mini-regattas, in events that were similar to those held during the International Regatta. At times, two thousand spectators would gather in the stands enjoying the warmth fade from the day as they watched their children compete. Those who were good enough joined the Ogopogo Summer Swim Club and trained to represent Kelowna and compete in other regattas. Youngsters swam, war canoe teams raced the half mile between the ferry dock and the finish line in front of the grandstand, and the audience yelled as youngsters tried to paddle their apple boxes to the finish line before the unwieldy crafts sank.

Waterskiing was also gaining in popularity by the late 1940s. Local athletes practised long and hard to complete the amazing 180- and 360-degree turns and then stay upright as they headed over the jump anchored in front of the grandstand. Adults came for lunch or tea on the veranda overlooking the pool and diving platform, danced to the music of Pettman’s Imperials at the Aquatic Ballroom or celebrated special occasions with Mart Kenney and his Western Gentlemen. Teen Town organized weekly dances in City Park for both local and visiting teens. Everyone gravitated to City Park and the Aquatic Club in the summer. The Regatta’s slogan—“No matter where you live, if the place is good enough to live in, it’s good enough to be proud of and to work for”—mirrored the community at the time: everyone was engaged, everyone was involved and everyone had fun. These were remarkable years for those who had the good fortune to live in Kelowna.

Neighbouring Communities

Okanagan Mission

Aside from the turmoil of young people departing for war, the Mission community had remained relatively unchanged and was still defined by its earlier British roots. More newcomers arrived to clear the hillsides and plant the recently introduced dwarf fruit trees. The community hall—the Red Barn—became the gathering place for badminton, tennis, Boy Scouts and Girl Guides, while the Eldorado Arms added a few attractive cottages for the guests who came to enjoyed the rural setting and the bit of Britain that still remained.

However, change was on the way for the Mission. The old Bellevue Hotel was finally demolished in 1954; though it hadn’t been used for years, its decline mirrored the end of the Okanagan Mission townsite. The post office and general store remained but people were more mobile and the community no longer needed its own commercial centre. The Courier reported that everyone was “up in arms over the appalling condition of the highway between Kelowna and Okanagan Mission.” Petitions circulated asking the Department of Public Works to finish the road to Kelowna and pave it—loose gravel had been left sitting on the surface, ruts were six to twelve inches deep, windshields were being broken and driving was hazardous.

Rutland

Rutland was rural and the majority of its citizens wanted it to remain that way. When the subject of incorporation came up at a community meeting in 1948, “spirited and impromptu speeches” resulted in a convincing vote to leave things as they were. Citizens nonetheless wanted some of the amenities of a town and in 1948 agreed to build a new junior and senior high school for students from the surrounding rural areas.

The biggest issue was whether Rutland’s airport would prevail over the upstart Kelowna proposal. Various air vice marshals visited the valley and said the surrounding mountains were a major impediment to any landing field. They did, however, concede that amphibious air service might be a good alternative. Short-haul flights didn’t make economic sense, yet perhaps shipping fruit by air would be viable. Cargo planes would have to be developed unless air force Lancasters could be converted, but the downside of the large planes was that longer runways would be needed. Glider trains might be an option… but again, only for long-haul flights.

All this postwar conjecture did nothing to quell the enthusiasm of members of the Rutland branch of the BCFGA, who insisted a local airfield would better serve their orchardists. They doubted reports about problems with updrafts and down drafts, and with Gopher Creek nearby there was plenty of water to irrigate the grass runway. Prospects brightened when the Rutland field was given a temporary federal operating licence for light aircraft, though it was conditional upon certain improvements being made. Prevailing winds would require two landing strips, one of which would have to be built across Belgo Road; loose rocks had to be removed from the runway, and nearby trees had to be removed. The utility pole at the end of one runway would also have to be removed, and a wind indicator, a telephone and a refuelling facility added.

The field was being used sporadically but things picked up when two former RCAF instructors arrived with plans to form a flying club, train student pilots and establish an “airpark” for tourists. They were certain the existing Rutland field could handle the traffic better than Kelowna’s Ellison Field, as the town would likely have to extend its runway and buy expensive farmland to do so. The Kelowna Aviation Council pleaded for unity. The federal licensing agency suggested one airfield was adequate and the two communities should try to work out their differences. Rutland put up a good fight, but in the end Kelowna’s Ellison Field prevailed. Rutland’s proposed airfield was eventually subdivided for residential development and parks.

Glenmore

Glenmore remained rural during this period but its southern boundary was starting to look more like a Kelowna suburb. The hayfields near the city limits could easily be developed but the Pridham family’s 113-acre apple orchard became the first large orchard on the valley floor to be subdivided. A residential area was laid out with space for a future “high class shopping district.” Although it took a few more years to become a reality, the Capri Shopping Centre became Kelowna’s first, though many questioned the wisdom of the development being so far out of town. Adding the Capri Hotel was even riskier. The centre was developed by the Capozzi family, on the Pridham orchard property, hence the name: Capri. However, the surrounding communities had little infrastructure and the only way the new development could proceed was if Kelowna provided water and sewage services. The need to extend Kelowna’s boundaries soon became a hot topic of discussion.

Bennett Takes Over

Kelowna continued to be represented in Victoria by W.A.C. Bennett, but after sitting in the legislature for a decade, the self-styled “man of action” felt he had accomplished little. Rather than quit in frustration, Bennett crossed the floor and sat as an independent. Many thought his political life was over: he rejected the mainline political parties and they rejected him. He had become a nuisance.

The Social Credit Party had emerged in Alberta during the Depression. In spite of its unconventional and untried monetary policies, and a platform based on solidly Christian values, it had provided the province with a strong and stable government. When the party moved to BC, it did so without a leader and had little to hold it together. Although Bennett joined the BC Social Credit Party in 1951, he still wasn’t sure this would be his long-term political home and he wasn’t interested in being the party leader. The two mainline parties had agreed to implement the single transferable vote system for the 1952 election: electors were to choose their favourite candidate as number one, their next favourite as number two and their least favourite as number three. The Liberals and Conservatives were confident their parties would be voters’ first and second choices, and they would continue to run the province. When the CCF won the popular vote and the Social Credit (Socred) Party was most voters’ second choice, it was a shock. In the midst of the uncertainty, the Social Credit Party held their leadership convention and W.A.C. Bennett officially became their leader. And when the final count was announced, the BC Social Credit Party had won nineteen seats and the CCF eighteen, while the Liberals had six and the Conservatives four.

Though the Socreds were six seats short of a majority, Bennett rejected another coalition, manoeuvred and wrangled, and convinced a baffled Lieutenant Governor that he was rightfully the province’s next premier. On August 1, 1952, about seven weeks after the election, W.A.C. Bennett assumed the office and became BC’s first Social Credit premier. Bennett was a populist and readily connected with ordinary people and his fellow small businessmen more than with the business and social elites in Vancouver and Victoria. Social Credit’s popularity engulfed the province, Liberals and Conservatives were wiped out, and the single transferable vote system was soon eliminated. Bennett became the unique politician who not only had a vision of greatness for his province, but was also able to articulate it and capture the public’s imagination in the process. Bennett set the stage for a period of unparallelled growth in BC.

Moving On

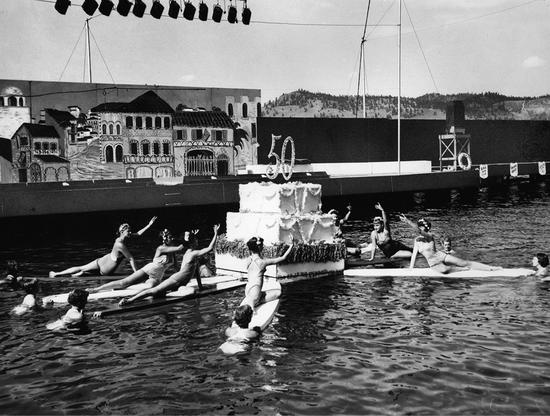

Kelowna’s golden jubilee, its fiftieth birthday celebration, was held early in May 1955. The Courier printed 13,000 copies of its eleven-section, eighty-eight-page Golden Jubilee Edition, though only 4,500 were needed for its normal circulation. Pre-publication sales were so brisk that the papers were sold out well before the actual celebrations; the Courier apologized—it had no idea there would be such demand. Everyone was involved in the celebrations and businesses took out full-page ads to let readers know how much they had contributed to Kelowna’s success during the past fifty years. The special edition featured year-by-year highlights along with pages filled with views of Kelowna in 1905 and then again in 1955: photos of the pioneer Lequime family were on one page while the photos of other pioneers, including Laurence, Christien, Postill, Brent, Mrs. Saucier and Dan Gallagher, were on another. A copy of the 1905 fire map identified the businesses along Bernard Avenue when only five hundred people lived in town, and told of how the volunteer fire brigade managed with a hand engine and four hundred feet of hose. Pictures of schools and churches, orchards, sheep and onion fields filled other pages. It offered readers a chance to look back at Kelowna’s history as well as marvel at how much things had changed.

Okanagan Investments, the successor to the 1909 Okanagan Loan and Investment Company, marked the jubilee by commissioning the city’s armorial bearings from the College of Heralds of Great Britain. The city had thought about having a coat of arms designed at various times, but never had the money to do so. The Courier likened the issue to “a woman desiring a diamond wedding ring but willing to wear the old plain one until the family finances could afford the one she desired.” The investment company made sure the correct and appropriate armorial bearings were designed, though the College of Heralds was likely perplexed by the insistence that a mythical sea monster needed to be included.

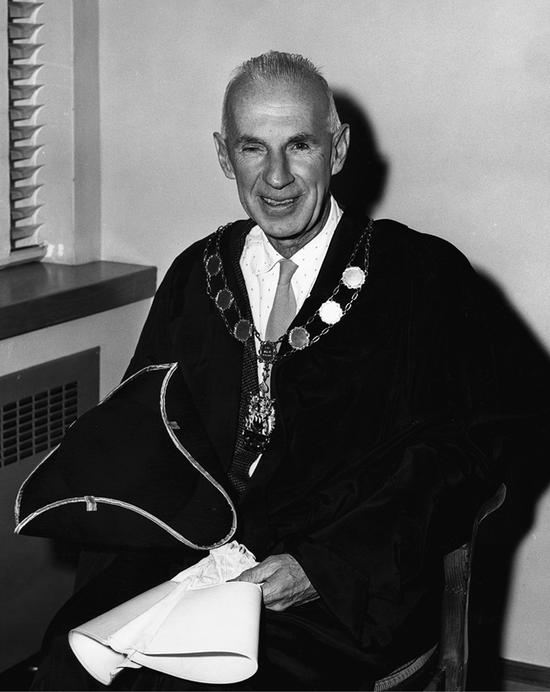

A brief ceremony was held in the Paramount Theatre on May 5, the actual date of Kelowna’s incorporation, when Mayor Ladd accepted the ceremonial regalia of office as a gift on behalf of the city. Few other communities of this size could boast such distinguished symbols of office, and certainly none in the valley. Only those who had lived in the city for fifty years or more, or represented businesses that had been in Kelowna for as long, were allowed to contribute funds to pay for the finery. The initial plan was to have the chain of office made of brass but the response was so “hearty” that the decision was revised to silver plated, and then real silver, then gold plated. As generous citizens donated even more money, the final chain was made of fourteen-karat gold. The cost was $1,500 but since $2,000 had been raised from the 122 donors, the balance was spent on the mayor’s official robes of office. They were to be patterned after those of the mayor of Vancouver and it took some time before the committee found a skilled garment maker who knew how to make the short slashed sleeves that would fall back to reveal the white kid gauntlets. A cloak and tri-cornered hat completed the ensemble.

About fifteen thousand people gathered along Bernard Avenue over an hour before the mile-long “50 Years of Progress Parade” got underway. With the Canadian Legion Pipe Band leading the way and the mayor in his new robes of office following, Kelowna’s history unfolded. Members of the Kelowna Riding Club, dressed in elaborate Native costumes, were followed by fur traders, gold miners, Father Pandosy, cow punchers and polo players. Many floats showcased the community’s recreational opportunities and the Lady of the Lake added a touch of class, while a float with a replica of the recently proposed Okanagan Lake Bridge caused great excitement. Lumberjacks carried logs and squirted the crowd with their modern firefighting equipment; fruit salesmen pushed wheelbarrows loaded with apples; costumed Japanese residents featured old-time transportation; and apple packing techniques and the new mosquito control truck drew great applause from spectators. The Chinese community’s float depicted their progress from coolies to cap-and-gowned college graduates. Volunteer firefighters brought the parade to a close with their old hose and reel equipment and their new modern steam pumper trucks.

Old-timers were honoured at a civic banquet later that day and two ladies who had each lived in the area for eighty years cut the cake. The cake was a replica of the twenty-seven-foot-high plywood cake on display at the end of Bernard Avenue. With the wonders of remote technology, another of the old-timers at the banquet flicked a switch to light the neon candles on the downtown cake. The evening wrapped up with the Gay Nineties Review at Memorial Arena. At a time when nine thousand people lived in Kelowna, about eigth thousand jammed into the building for the 8:30 presentation while another five thousand attended the 10:30 performance. Between shows, everyone joined the old-timers as they took over the floor and danced their collective hearts out. Kelowna gloried in its fifty years of progress and its citizens unabashedly celebrated their wonderful community, its unmatched lifestyle and its limitless opportunities. It had been quite a week… and quite an amazing fifty years.

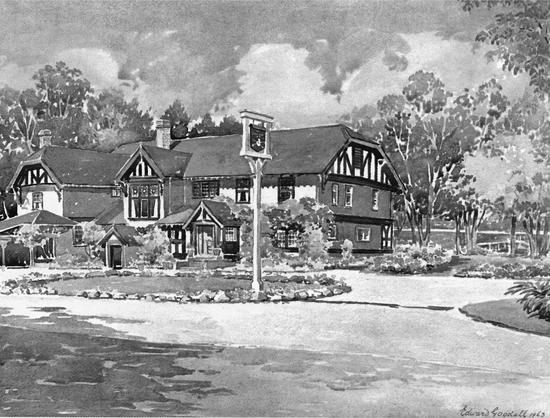

The Kelowna Board of Trade published a new promotional brochure in 1949. Photos showed a wide and busy Bernard Avenue and told of the gracious lifestyle led in the elegant homes scattered along the lakeshore. Other pictures showed a community with all the amenities prospective residents could possibly want: a new hospital, new schools and an abundance of sports and recreation opportunities. Kelowna was “the Heart of the Okanagan… where people lived by choice…’neath the rays of a benevolent and almost constant sun.” Readers were invited to make Kelowna their home, and during the years that followed many accepted the invitation.