Chapter Four: And We Thought We Would Be Spared, 1930–1940

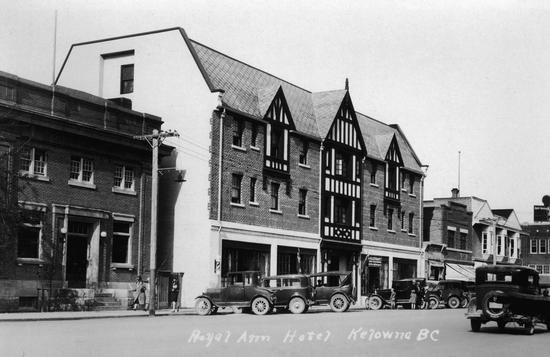

The Depression was slow to arrive in Kelowna. So slow in fact that many were saying it really wasn’t a Depression at all, just negative thinking, and if we all pulled together and thought more positively, everything would be fine. The previous twenty-five years had been eventful for the new community and about 4,500 people now lived in the town and surrounding areas. There were few signs that life would not continue as it had been, and news stories in the Kelowna Courier were about valley-wide badminton tournaments and whether the Kelowna Growers Exchange was a better way to sell apples than the wherever, whenever tactics of the independents. Yet all was not well. The Royal Anne Hotel’s New Year’s Eve celebration in 1930 was marred by the death of a young man who climbed outside through a small third-storey bathroom window thinking he could cross the narrow gap and climb back in through the adjoining bedroom window. The sheer brick wall gave him little to hang on to and he fell to the street. By the time Dr. Knox was called from the dance floor inside the hotel, it was too late. It was not an auspicious beginning to what would become a troubled decade.

Though the CNR had arrived a few years earlier, Kelowna was certainly not on the mainline. The train pulled into the station, stayed for an hour or so and departed on the same track: Kelowna was a destination, and an unlikely stop on the way to anywhere else. The community remained somewhat isolated and the first news that times might get tougher was a paragraph in the newspaper about plunging Prairie wheat prices. Then the apple shippers started having trouble getting the prices they wanted for the remainder of the 1929 crop.

Otherwise, life in the area was more or less unchanged. The hospital held its annual egg drive and collected two to four hundred dozen eggs, which were preserved in waterglass to keep them fresh; the talkies were showing at the Empress Theatre and matinees cost fifteen cents; and electric refrigerators with the motor on top began replacing ice boxes. Tobacco was still trying to make a comeback, but while the Okanagan product was of good quality, marketing had been a disaster and more money had been lost in various tobacco ventures than with any other crop grown in the valley. The Royal Anne Hotel and the Eldorado Arms in Okanagan Mission remained busy with parties and celebrations through the troubled years ahead, even if there were fewer out-of-town visitors.

Then, oil was discovered—or at least the likelihood of oil—in the bowels of the earth in East Kelowna—or Okanagan Mission, or Bankhead—and the promises of promoters galvanized the community in the dreary winter of 1930. A local syndicate obtained leases and raised money, and a geologist, with the aid of a divining rod, agreed that a vast pool of high-grade oil would be found two to three thousand feet down. The junction of Mission and Canyon Creeks soon became the location of Okanagan Oil & Gas Company Well #1. Several hundred spectators arrived to watch the construction of the eighty-foot derrick, and later the building of comfortable quarters for the crew. Grote Stirling, MP, came to mark the “auspicious occasion” as Mrs. Rattenbury, the wife of the mayor, and Mrs. McKenzie, the wife of the promoter, broke a bottle of water over the rig (reflecting the lingering restraints of Prohibition). The International Pipe Line Company promised to connect Kelowna with Vancouver once commercial quantities of oil had been confirmed. Assurances were given that the Kelowna deposits would likely exceed those of the Turner Valley, in Alberta. The machinery ran twenty-four hours a day, schoolchildren visited the site with their teachers and the appeal for financial support continued amid promises of greater prosperity than anyone could ever imagine.

Then… equipment began to break down, the project was delayed awaiting replacement parts and investors were admonished that they must expect these kinds of setbacks. Ten months after drilling began, the crew reached 2,102 feet and gas was now suspected. It looked amazingly like the wells in Viking, Alberta, that supplied the city of Edmonton with natural gas! Then the drill broke and it took five weeks of “fishing” to dislodge and remove it. Delays and shutdowns seriously interfered with the promoters’ fundraising efforts early in 1932. Over two hundred people gathered a few months later to hear the company’s “frank” presentation about the undertaking. In spite of an Ottawa geologist’s negative report, several of those in attendance promised to give favourable consideration to the company’s appeal for just a few more dollars. Everyone was fascinated and hundreds travelled to the well site each Sunday to see progress unfold before their eyes.

A great flow of water was discovered at 1,900 feet, along with a black carbonaceous layer of shale… and then more water. Further delays followed but with funds arriving from investors in Nelson and Trail, drilling started again. Success was so close and the promoters were so doggedly determined—their faith in the project never faltered. However, as 1933 drew to a close, and after many stops and starts and explanations and assurances, the taxes hadn’t been paid and there was no money in the treasury, so the shareholders called a meeting and suspended operations. Drilling had reached 2,740 feet, yet the promoters pleaded with investors not to be discouraged as a rich oil field was sure to be found at just 3,500 feet…

The promise of oil was about the only bright spot in the community as the reality of hard times elsewhere in the country started to become apparent. The selling price of the previous year’s apples continued to fall as the new crop began ripening on the trees. Transients arrived in Kelowna for the 1930 picking and packing season and then stayed on. Kelowna formed a Central Relief Committee to augment the efforts of other levels of government in dealing with the unemployed and indigent, with each paying one third of the costs and the city administering the funds. With about 4,500 people living in Kelowna and the surrounding area, and 111 unemployed at Christmas that year—61 of whom were married, with 44 of those having one or more children—it was a considerable burden. Little did they realize that the number would double and then triple over the coming years. Single men were sometimes housed in the old exhibition building in the north end but they were evicted as soon as the weather turned warm. Other years, the building was rented to store unsold onions and the men were left without a roof over their heads.

Most of those arriving in Kelowna had jumped off the transcontinental trains at Kamloops and hitched a ride on the CNR southward. It wasn’t long before a “hobo jungle” appeared north of the tracks. It was called “Honolulu City” by its inhabitants, and whether the name was because it was that good or because it was as close as the inhabitants were likely to get to the real thing has been lost to time. Unlike many other “jungles,” Kelowna’s was an orderly place with rules and regulations, and was organized enough to send delegations to city council to lobby for better conditions. Council was dismissive, as the men were not Kelowna residents and they had no right to petition on any matter, and sent them to the provincial government office. When council asked why they shouldn’t call out the Rocky Mountain Rangers to run the squatters out of town, they were told that such action would result in the men scattering and likely sleeping in people’s cellars, camping in their barns and perhaps even stealing whatever they could lay their hands on. It would be wiser if council let the orderly Honolulu remain as it was.

Residents who still remember those times recall few problems. Men would knock on doors offering to work for a meal and then leave a coded message scribbled on the gatepost so those who came along later would know if the householder was generous… or not. If specific skills were needed, locals would head to Honolulu looking for a paper hanger or a painter and usually returned home with the helper they needed. In the early years, Kelowna developed a number of water and sewer projects to employ the transients, but those opportunities soon vanished and the single men either left town or went to the federally run relief camps. There was no point in allowing women to register for relief as no suitable employment was available for them.

The federal government became increasingly alarmed at the political agitation, anger and unrest infiltrating the ranks of the unemployed. By 1932, several relief camps had been set up across the country. Two of these “concentration camps,” as the locals called them, were nearby: Wilson’s Landing on the west side of Okanagan Lake just minutes from Kelowna, and Oyama, along the road to Vernon. Men were sent out each morning with picks, shovels and wheelbarrows to build roads and survey camps. They soon became known as the Royal Twenty Centers, as that is what they were paid each day for their efforts. Rather than containing the disenchanted, the camps proved to be a fertile breeding ground for Communist agitators and recruitment centres for the protest marches that marked the Depression years.

Madman on the Loose

Life in Kelowna was usually uneventful and the town’s history held little drama. That changed early in 1932 when the Courier’s headline read: “Death stalked in the wake of a madman on Tuesday afternoon, when this Okanagan city was the scene of two cold-blooded murders.” On January 19, between the hours of five and six p.m., Chief Constable David Murdoch murdered Jean (Genevieve) Nolan and his former deputy, Archie McDonald. Miss Nolan had been shot in the rotunda of the Mayfair Hotel (earlier named the Lake View Hotel) where she had sought refuge from the gunman. The ex-deputy had been shot in his own home, just minutes away, on Lake Avenue. Word of the murders spread quickly and people were panic-stricken: doors were locked, porch lights were turned on, and people fled downtown. Terrified residents were even more alarmed to hear the murderer had visited the offices of the lawyer, T.G. Norris, and the police commissioner, Dr. Boyce, within that same hour.

By seven that night City Constable Sands had been advised that the murderer was likely Murdoch and went to the chief’s house to take his wife and son to a safe place. Before doing so, and while other officers watched the house, Sands went to a nearby telephone office and called the chief’s phone number. When the son answered, he assumed that only the child and his mother were at home and returned. When Mrs. Murdoch opened the door, the constable immediately spotted Chief Murdoch’s blue coat and fedora lying on a chair. Quickly drawing his pistol, Sands walked into the kitchen and found the fugitive calmly sipping a cup of coffee. Declining the offer to join him, Sands arrested his chief and took him down the street to the lock-up.

An inquest was held the following day and as the details unfolded, the newspaper pondered the motives for such drastic behaviour. It also cautioned readers that the police chief had not yet been found guilty and, in the best traditions of British justice, he was not guilty until the court made that finding… and then speculated as to why Murdoch had murdered his two victims. Jean Nolan, the pretty auburn-haired girl who was twenty-four or -five, had been in town only a few days but was a known police informer who might have worked with Murdoch before he came to Kelowna. Dr. Boyce later testified he was sure she was at least thirty. Archie McDonald and the chief had also been involved in an altercation during the previous year’s Regatta, and Murdoch was reportedly convinced his subordinate intended to kill him. The deputy had been charged with assault, and when the charges were dismissed Murdoch felt the court had “crucified” him. McDonald lost his job in spite of his innocence.

Several witnesses testified at the preliminary hearing a few days later and a different story began to unfold. Questions were raised about Murdoch’s mental state and when local doctors were asked about his condition, they said he “was in an unbalanced state of mind at the time.” Letters written by Murdoch to Nolan were introduced: some were in verse; some rambled on for pages; some were signed, others were not. The game warden, Mr. Maxson, who doubled as a special constable, said they had all been written on the police station typewriter. Nolan had subsequently given the letters to McDonald who passed them on to the clerk at Mr. Norris’s law office; Norris had represented McDonald on the dismissed assault charge.

Jean Nolan had been shot at seven times: Murdoch fired on her twice outside the hotel and five times in front of the dining room doors in the hotel’s rotunda. One bullet pierced her heart and witnesses claimed she was still moaning when Murdoch ran from the hotel. None of the bullets stayed in her body and those shown in court had been extracted from the door frame of the lobby’s telephone booth and from the dining room floor. Murdoch had run from the hotel, through the main entrance to City Park, past the playground, past the baseball diamond, across the bridge and onto Lake Avenue, where he made his way to McDonald’s house. The ex-deputy was found on the kitchen floor with his hands under him, his legs crossed and a broken dish of vegetables on the floor beside his head. There was no pulse. Though some witnesses had trouble identifying Murdoch in the January gloom, a distinctive notch on the heel of his boot had left a clear track in the snow and his route had been easily identified. Mrs. Murdoch, who “controlled her emotions well,” sat in the courtroom all day. Murdoch was committed for trial and held for five months at Oakalla Prison, near New Westminster, until the spring assizes in Vernon.

After hearing more or less the same evidence admitted at the preliminary hearing, the jury deliberated for three hours before returning to the courtroom to admit they were unable to reach a verdict. Five months later, a second jury was called to hear the evidence at the fall assizes. It was more or less the same evidence as had been heard at the first trial. The jury deliberated for another three hours before returning to the courtroom to declare they too could not agree on a verdict. The defendant never testified and his counsel never challenged the facts: he had murdered the two victims. Neither jury could reach agreement on the defendant’s mental state: had he been sane… or not?

A third trial got underway a week later and this time both sides called in medical experts from New Westminster and Vancouver and delved deeper into the chief’s past: he had been an illegitimate child and felt everyone was against him because of it. He obsessed and blamed his past failures and job losses on the circumstances of his birth. He had initially felt Kelowna was remote enough that his past would remain hidden, but his behaviour had recently become strange. Those who noticed thought he was overworked and that a holiday, or less work, or going to church, would cure him. When a colleague from Penticton told him that Nolan was a dope peddler and a prostitute, Murdoch called her a “wrecker of men’s souls” but remained convinced she was still the only woman for him. When he discovered that Nolan had delivered his precious letters to McDonald, Murdoch either lost contact with reality or planned the murder of his victims.

The experts diagnosed Murdoch with “paranoia simplex… which causes the patient to suffer the delusion of persecution. The progress of the disease was typically slow and is usually more pronounced in middle life.” They said the patient simply did not know what he was doing when he fired the gun and was not capable of the intent to murder. By then, everyone was getting tired of the case. When the third jury had been deliberating for five hours, the judge called them back to the courtroom and told them he would not accept another disagreement. An hour later, the jury returned with a guilty verdict, though they added a strong recommendation for mercy because of the defendant’s proven mental instability.

The judge refused to accept their verdict so they had to make a choice: either a clear verdict of guilty or a clear verdict of not guilty because of insanity. The jury finally agreed to the latter. Murdoch was committed to a mental hospital for the criminally insane for the remainder of his natural life. The conviction was for the murder of Jean Nolan, and he was never charged for the murder of his former deputy.

Glimmerings of Hope

As the Depression deepened, more of Kelowna City Council’s time was taken up dealing with the fallout: the federal government’s count of the unemployed didn’t match the city’s and the funds the city was sure they were owed didn’t arrive. With less tax revenue, city staff were forced to take pay cuts and then the hospital wanted to know who was going to pay for the men coming in from the “concentration camps.” Relief for work was a nationwide mantra even if “work” meant selling apples on a street corner: that, at least, was better than standing in line for the dole. City council worried and sent notices to all householders warning them to save their wages and store and preserve fruits and vegetables.

Although unemployment and a sense of hopelessness pervaded much of the country during the 1930s, Kelowna moved on, sooner than most cities. By the end of the decade, voters approved tax hikes to pay for new schools as well as a concrete and fireproof hospital.

W.A.C. Bennett—Cecil, or “Cec” as he was known to his friends—arrived in Kelowna with May, his wife, and children Russell (R.J.) and Anita at the beginning of the 1930s. He had been involved in the hardware business in Alberta before deciding to look for opportunities in BC. Perhaps foretelling later developments, the Bennett family had to travel through the US to get to BC, as no highway yet connected the two provinces. The thirty-year-old Bennett first headed to Victoria but decided there might be better opportunities elsewhere, and soon discovered that David Leckie, Kelowna’s hardware merchant since 1904, was looking for a buyer for his business. Bennett bought the hardware store and the two-storey brick building on Bernard Avenue, and then spent the rest of the Depression watching the inept and inadequate handling of Canada in crisis by his own Conservative Party and then the Liberals.

Because a number of Bennetts had already settled in Kelowna, Cec decided he needed to establish his own identity—and hopefully get his own mail—and soon became known as W.A.C. Bennett. Two years after arriving in town, a second son, Bill, was born. Cec joined a number of local business and social groups and then became involved with the local Conservative Party. He sought to become the party’s candidate in the next federal campaign but soon realized the incumbent was well-entrenched and that it made better sense for him to turn his attention to provincial politics. The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) had arrived in BC early in the Depression and before long had both radicalized and polarized the province’s politics. As if biding his time, Bennett opened hardware stores in Penticton and Vernon and, although he was a teetotaller, joined his friend Cap Capozzi in a new business venture that soon became Calona Wines.

Bennett sought the Conservative nomination to run in the 1937 provincial election. He lost the nomination and his party lost the election, and his aggressive, independent style didn’t endear him to his party’s brass in Vancouver. He sought the nomination again four years later, and by that time had won over both the brass and the community, and soon headed to the legislature in Victoria. His arrival coincided with the release of the report of the Royal Commission report on Dominion–Provincial Relations, which identified BC’s historic role as that of the spoiled child of Confederation. It offered the opinion that the province would never amount to much: it was isolated by the mountains, would probably always be in political chaos and would never have the wealth of the other provinces. No party held the majority in Victoria, and the Liberals and Conservatives formed an uneasy coalition to hold onto power. Much to the surprise of many, the CCF won the popular vote and became the official opposition. The coalition was plagued by infighting, the policies of the two parties were indistinguishable, little was accomplished and Bennett became frustrated. However, Kelowna now had a presence on the provincial stage.

In other areas, Kelowna was becoming less isolated when new technology connected it with the rest of the world. The first commercial radio station, CKOV, “the Voice of the Okanagan,” emerged from an amateur predecessor thanks to James “Big Jim” Browne and his wife, who had arrived in Kelowna in 1914. Jim got his start with the amateur station but was intrigued with its potential. Finally granted a commercial broadcast licence in 1931, Jim soon began airing live broadcasts from a tiny house on Pendozi Street. Two ninety-foot cedar poles had been erected in the corner of the nearby Kelowna Saw Mill yard as transmitters. A carpet hung from the ceiling of the station to deaden outside noises, listeners loaned both recordings and money and the station’s salesmen flourished. CKOV quickly became the voice of the community: lobbying for civic improvements, suggesting ways to control those pesky mosquitoes, reporting apple prices and broadcasting live lacrosse games from City Park and basketball games from the Scout Hall.

The station outgrew the house and needed a more secure transmission, so it moved to a new site on Lakeshore Road in 1938. Soon after, the CKOV signal was being picked up beyond Kelowna. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) was threading its way across the country at the time, and when Britain declared war on Germany in September 1939, the CBC withheld the news. Prime Minister Mackenzie King needed time to decide if Canada should join Britain or not and wanted to make the decision before telling the country. Big Jim had been monitoring US broadcasts and felt no compunction about keeping his listeners up to date on unfolding world events. Ottawa somehow heard of CKOV’s unauthorized broadcasts and was not amused. The following day the station received a telegram telling them to cease and desist or risk losing their broadcast licence.

The Kelowna Courier had been a part of the community since 1904. Originally it was the Kelowna Clarion, then the Kelowna Courier and Okanagan Orchardist, and finally, with a new editor and publisher in 1939, it was renamed the Kelowna Courier. Early issues usually reflected the owner’s view of the world—his politics, stand on local issues and general opinions—and were rarely unbiased or neutral. When the Depression took its toll on both circulation and advertising revenues, the Courier was sold to a company jointly controlled by the Penticton Herald and the Vernon News. Kelowna lost its independent voice. But when R.P. McLean arrived in town in 1938 and purchased the paper, he promised more balanced reporting and committed to print all the news, even if some people didn’t want to see their names in print—they should have thought about that before they committed whatever it was that caught the editor’s interest in the first place.

Aside from the Murdoch drama, life for many in Kelowna remained relatively unchanged during the Depression. A few businesses continued to advertise in the Kelowna Courier and Okanagan Orchardist, the Royal Anne Hotel and Eldorado Arms were busy, and a campground had been set up in City Park, though most acknowledged that cabins would attract a better class of visitor. The elegant Willow Inn Hotel had been built in 1928 and linked to the nearby Willow Inn Cottages by a garden surrounding a fountain and goldfish pond. Located between Bernard Avenue and the Kelowna Saw Mill across from the ferry wharf, it became so popular that Willow Lodge, built from cedar logs trucked in from Lumby, was added in 1935. Both locals and visitors lounged in the gardens, played and partied on the beach, and moored their boats in the bay beside the public wharf.

Too Many Apples

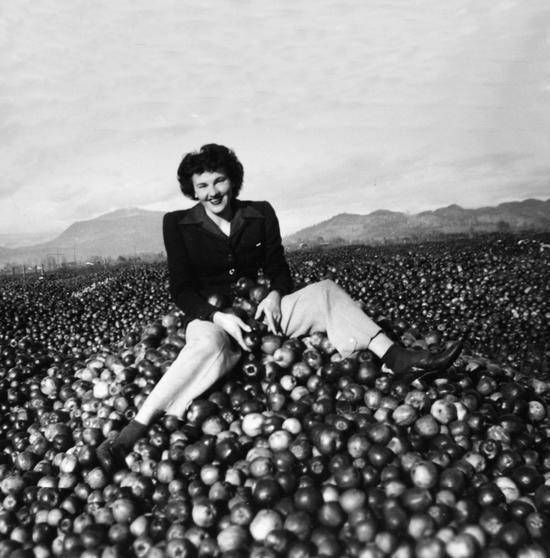

Few if any new orchards were planted in the Okanagan during the 1930s, though the weather that created the Prairie dust bowls made for near-perfect growing conditions in the valley. Orchards planted during the previous decades were maturing and producing more and more apples just as Prairie residents could no longer afford them. Also, so much emphasis had been put on production that the quality of the fruit began to suffer. There were too many culls—the undersized, insect-damaged or poorly coloured apples—and the packinghouses didn’t know what to do with them. Orchardists had to pay to prune, thin and spray, pay their packinghouse to grade and pack, and then pay shippers to sell and deliver their apples to the wholesale market or fruit jobbers. It wasn’t long before orchardists realized the apples that weren’t good enough for the fresh market would cost them money. They had few options other than leaving them on the trees, ploughing under or hauling them to empty lots and leaving them to rot.

There was little to be optimistic about in the apple business and it wasn’t the best time to try something new. Desperate times, however, demanded action. Louis Deighton from Oliver, at the south end of the Okanagan Valley, heard that Sunkist of California had just introduced the first fruit juice to the market. There was little to lose, and he figured he should be able to produce something similar with apples. With help from Ottawa and borrowed equipment, he experimented and improvised, and produced 1,500 cans of clarified apple juice in his first year of production. However, it wasn’t an easy sell and his backers thought it was too much effort for such a small return, and abandoned him. Undeterred, Deighton produced forty thousand cans of juice the following year and then travelled the Okanagan and the Kootenays promoting and selling his new product. On a hunch, he sent juice samples to Vancouver General Hospital; when they ordered two thousand gallons, he knew he was on the right track. It wasn’t long before the packinghouses began paying growers for their culls.

Initial juice production was low, though the Vernon Fruit Union got on board and began making juice at its Woodsdale plant in Winfield. The investment soon paid off when the Department of National Defence bought the valley’s total output of juice during the war. Kelowna took awhile longer to get into the juice business. Modern Foods Ltd. began dehydrating apples in 1937 and went on to turn the peelings and cores into vinegar. The first year’s operation wasn’t a financial success and the plant closed. The following year, another group formed the Kelowna Vinegar Syndicate and processed five hundred tons of cull apples into vinegar. It didn’t sell and they too closed their doors. Gallons of vinegar were left behind along with a bill from the Kelowna Growers Exchange for the apples. Since the packinghouse didn’t want to refinance the syndicate and no one else wanted to buy the vinegar, the KGE was left with a loss. Their manager, Bill Vance, didn’t agree with the KGE board and was convinced apple by-products would be the growers’ salvation. He put up his own five hundred dollars, bought the defunct plant and the vinegar, adapted his mother’s pickle recipe to commercial quantities, and turned Mrs. Vance’s Commercial Relish into a bestseller.

In spite of the successful relish, few apples were being diverted for dehydration, juice or vinegar. Orchardists were becoming increasingly desperate as the bills were piling up and no one was buying their apples. The majority agreed to pull together and to market and ship together. They also agreed that they would not bulk load the apples directly into the boxcars, though they knew this was a cheaper way to get their apples to market. A few independents remained, still determined to sell to anyone, wherever and however they could find a buyer. The two sides negotiated for days and finally agreed to have a single marketing and shipping plan. The independents later declared they had been intimidated and threatened, and felt they had little choice but to agree.

The growers were desperate. They decided they wouldn’t deliver their apples to the packinghouses unless the shippers guaranteed them one cent a pound, or forty cents a box. If the shipper would not or could not make such a guarantee, growers would dump their apples before being charged for grading, packing and shipping. Vigilantes manned the three bridges into town from the surrounding apple-growing areas. They would not tolerate any monkey business. If truckers didn’t have a written statement from shippers agreeing to the growers’ terms, they were turned back. These were unprecedented measures but these were also unprecedented times: if the growers stepped beyond the boundaries of the law, well, so be it. It was war, and the growers’ rallying cry of “A cent a pound or on the ground!” reverberated throughout the community.

Then word reached the organizers that railcars were being bulk loaded with orchard-run McIntosh Reds at the Rutland Cannery and Joe Casorso’s Belgo Co-op packinghouse. The call went out and growers downed their tools, leapt in their trucks and raced to the cannery. Loading stopped immediately, and a council of war was convened. Mr. Cross, the cannery manager, denied any knowledge of the regulations and said he was only carrying out Mr. Casorso’s instructions. Enraged growers wanted to unload the car but finally agreed to seal it before jumping back in their trucks and heading to the Belgo packinghouse. Another car of mixed-grade McIntosh Reds was being bulk loaded, again on Mr. Casorso’s instructions. The manager was given the choice of having the growers unload the car or having it sealed. He chose the latter. Mr. Casorso, they were told, was in Vancouver and could not be reached.

Meetings were held up and down the valley to sign up other orchardists. It took a couple of weeks before things began to unravel. Joe Casorso, son of Giovanni Casorzo, who had extensive holdings in the Rutland area, had convinced the Rowcliffes at Hollywood Orchards and their growers (mostly “foreigners”) that their salvation lay in the bulk shipment of apples. They were adamant and claimed they’d “blow to hell” anyone who laid a hand on their fruit. The police were called to the packinghouses and although the crowd remained orderly, power was cut to the loading bays and windows were broken. Bonfires were lit beside the tracks as sympathetic citizens gathered and handed out coffee and refreshments. Casorso promised not to move any cars that night.

It didn’t take long though for rumours to start up again: two… and then seven railcars of apples were reportedly being bulk loaded. The growers pleaded with local railway agents and then sent telegrams to the presidents of the CNR and the CPR. When they didn’t get a response, they sought an injunction against the railways to prevent them from moving the cars. That involved a trip to Vernon and back, finding the appropriate judges and preparing the legal papers, and growers were worried the trains might leave before the injunction could be served. A call went out to mobilize. The group said they were not promoting any unlawful activity, only mobilizing their supporters in an act of self-defence. If it was unlawful for them to lay hands on the loaded cars once the railway had taken charge of them, that was fine, but they also noted that it was not an offence to stand on the railway track.

So they did. The head of the growers’ group declared, “We are peaceful citizens defending our right to live. We will take a walk on the railway tracks and if I lie down and go to sleep on the ties, I will expect you to see that I am not run over by a freight train.” The women and children were less restrained with cries of “Over our dead and mutilated bodies!” Train crews, not surprisingly, backed off and the growers and their supporters gathered around bonfires and sang well into the early morning.

The Kelowna growers won that battle but the war continued. Orchardists from the Kootenay, Creston and Grand Forks areas hadn’t signed on to the cent a pound campaign and continued to sell their apples anywhere they could, for whatever price buyers were prepared to pay. As it turned out, Kelowna’s growers shipped their apples later in the season and most sold for more than the cent a pound they had been demanding. Marketing by co-op, individually or by legislation remained a thorny issue in the industry for many years.

A Valley First: Domestic Winery and By-products Ltd.

The wine industry arrived in Kelowna in 1931. Though prohibition was no longer the law, the government restricted liquor sales and the Vancouver Sun declared that “the establishment of wine industries in British Columbia is a step towards the reduction of alcohol consumption. It is a step towards temperance and towards real moderation.” Giuseppe Ghezzi, a representative of wine expert Professor Eudo Monti, Ph.D., of Turin, Italy, had just come to town, bringing samples of wine and cider made from Okanagan apples shipped to the Old Country. The beleaguered orchardists were hopeful that a new apple-based wine would use a good portion of the apples they would otherwise be throwing away.

A syndicate was formed with a well-connected board of directors, including teetotallers, hardware merchant W.A.C. Bennett and grocer Pasquale (“Cap”) Capozzi. Their company was called Domestic Winery and By-products Ltd., and they ordered their machinery from Italy. Mr. Ghezzi’s son Carlo arrived to become the winemaker and Professor Assenelli, a chemist and specialist in sparkling wine and champagne, also came to lend his expertise. A cement building in Kelowna’s north end became their winery, a refrigeration plant was added and four thousand gallons of apple juice was soon ready to be made into apple wine. Later, apple juice was added to Concord grape juice to make the Italian-style wines as well as their premium champagne.

The following year, BC government liquor stores ordered a thousand gallons of wine and the company began selling the “Okay” label in attractive twenty-six-ounce and gallon jars: there was Okay Clear, a sparkling white wine, and Okay Port, a rich flavourful red. Doctors in town for a medical convention the following year visited the plant and without exception heartily endorsed its wine. The local newspaper was somewhat reserved in its assessment and noted, “it is not unlikely that this will become one of the Valley’s most important industries.” Kelowna’s Italian community was enthusiastic and many worked in the plant, while others became shareholders.

Some orchardists were a bit dubious about the viability of the new industry, though the public flocked to demonstrations and eagerly sampled the new product. As the market grew, the company realized that its “Okay” branding wasn’t very optimistic and in 1936 ran a province-wide competition to come up with something classier. The winner was from the Fraser Valley: the suggestion of “Calona Wines” was seen as much more suitable. Giuseppe Ghezzi soon moved onto the Yakima Valley and eventually California, though his son Carlos Brena Ghezzi continued on as winemaker. Calona Wines became a familiar brand in the government liquor stores: the twenty-five-ounce Calona Champagne cost $1.90; the forty-ounce Calona Red, seventy-five cents; and a gallon of twenty-eight-percent proof Calona Dry Red, Italian type, $2.85. It was just the beginning.

An Established Business Expands

At the onset of the Depression, Stan Simpson was already building his new sawmill at the Manhattan Beach location. A veneer plant was soon added, though box production remained at the Abbott Street plant. When growers began using sacks instead of boxes and then bulk loading their apples, Stan must have wondered if he had a future in the business. The success of the Cent a Pound campaign sustained him for awhile, but he knew he would have to adapt. When the new box factory opened at Manhattan Beach in 1933, the assembly line ran round the clock to build a simpler, lighter, topless crate that held fifty pounds of apples.

As Simpson had planned, the veneer plant gave the company more flexibility and it soon began manufacturing veneer berry boxes, tin tops and grape baskets. The companies that had previously been supplying these containers, for resale to the growers, soon began a price war. Undaunted, Stan continued producing—and the outsiders eventually gave up. The logs used in the veneer plant were dumped in vats of hot water to soften the wood before long thin sheets of veneer were peeled off, scored and made into berry boxes and tin tops. By the mid-1930s, between 1.25 and 1.5 million tin tops were being produced each season. Sheets of tin measuring twenty by sixteen inches and six inches thick were shipped from England and on to Kelowna by rail; a single layer would cover the floor of the car. The tin was cut into narrow strips that would be wrapped around two pieces of veneer while a leg-operated crimper secured the tin around the top of the basket. It was a hazardous job as the tin was sharp and gloves didn’t help. Most of the women operators said their hands toughened up by the end of the year. Experienced workers could produce about 2,000 containers on an eight-hour shift. About 940,000 tiny veneer berry cups were also stapled together and packed into two-layer crates before being shipped to North Okanagan strawberry and raspberry growers. About 75,000 grape baskets were made and assembled annually for the table grape industry.

Apples were always shipped out of the Okanagan Valley in new wooden boxes. But the solid lids were replaced by veneer tops and bottoms, and since Stan Simpson had the only veneer plant in the Interior, the company made and sold the lids to other box manufacturers. Over 10 million were made in a season. With the new sawmill on the lakeshore, logging contractors dumped their logs at various booming grounds around the lake where they were picked up by a succession of company-owned tugs and hauled to the mill. The first tug, the Klatawa, was bought from ferry captain Len Hayman in 1932.

During the Depression, small groups of men would gather outside the mill office looking for work even when they knew none was available. Other times a few old employees would arrive, load the sawdust trucks and deliver the fuel to homeowners who had no other way to heat their houses. When he had no money to pay them, Stan told his workers to go to Capozzi’s City Grocery and charge what they needed, and he would guarantee their bill. He rarely, if ever, had to cover a bad debt. By 1937, when the politicians were insisting the worst of the crisis was over, fire wiped out Stan’s office and his blacksmith and machine shops. The midday July winds were fierce and most of the efforts of the firefighters were used to prevent the flames from leaping across the narrow road to the sawmill and box factory. The cause of the fire was never discovered and crews soon set about replacing the buildings.

Two years later, when the box factory was running round the clock to ensure enough boxes were ready for the upcoming fruit season, an early morning fire destroyed the sawmill and veneer plant. Only the heroic efforts of the firefighters saved the box factory. A bottle of kerosene and oiled rags were discovered two days later behind a pile of lumber. The fire was of “incendiary origin.” Stan set up a portable mill in the yard, added an extra planer to the one that had been rescued from the burning sawmill and began cutting lumber for the box factory. He also cut the heavy timbers needed for the joists in the new sawmill and veneer plant. The packinghouses got their boxes on time, and Stan searched for the best and newest sawmill and veneer plant equipment from across the continent. The veneer plant was back in full operation by July 1939, though the building was still without its roof. The portable mill kept producing lumber until the beginning of September when the new sawmill could be started up. By that time, Canada had declared war on Germany.

Kelowna Waits Impatiently

Kelowna was exasperated with the MV Hold-up as it continued to live up to its reputation for terrible service. Car traffic had increased but the ferry could still only carry its original fifteen cars, and angry drivers and passengers were left waiting endlessly for later sailings. Winters had been so cold that the lake froze over several years in succession and the ferry was left icebound. Passengers waited and waited, businesses ran out of supplies and politicians were immune to pleas for help.

The community was so fed up they decided to solve the problem themselves. Father Pandosy’s old trail had always enticed people into thinking that a road along the east side of Okanagan Lake was a possibility. The road south from Kelowna had been started a few years earlier and a survey camp had been built by men from the relief camp, but little real progress had been made. Things were more promising at the other end as a road between Penticton and Paradise Ranch, just beyond Naramata, was already built. From there, however, narrow footpaths and animal trails were the only way to reach Okanagan Mission.

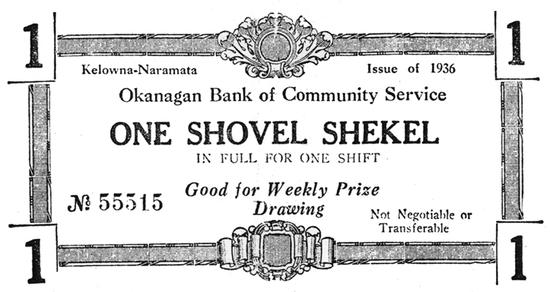

Not everyone thought the road was a good idea, but when word of the project starting up again got out, the Courier reported that the news spread “like wildfire and has enthused hundreds of persons.” The Kelowna Board of Trade mobilized volunteers: bulldozers were offered and work parties blasted rock, dug through the clay banks, toppled trees and worked with such enthusiasm “they put paid labourers to shame.” Money poured in to buy dynamite and blasting caps. Thursdays and Sundays were workdays. Women turned up to provide tea and coffee for the workers and a few of the hardiest grabbed shovels and worked alongside the men. All were paid in “shovel shekels,” which were redeemed for free goods or entered into a weekly draw for donated prizes. News of the project and the shekels spread to the coast and it wasn’t long before stories began to appear in the Toronto Mail and Empire and the Halifax Herald.

The planned road from Cedar Creek though Wild Horse Canyon to Paradise Ranch would be sixteen miles long. Old logging roads could be incorporated in some areas, bridges had to be built across several creeks and the formidable grade from the lake to the entrance of the canyon had to be conquered. Most volunteers were unaccustomed to hard physical labour and sometimes fewer than anticipated arrived for their shifts. When work crews reached Deep Creek, they “hurled up a cabin… of neat appearance in a day with a husky door, three well fashioned windows and a hand carved sign over the door declaring it Kelata Kabin.” It was ready for anyone who wanted to spend a night or a week or two in the wilderness.

“On To Naramata Week” was declared in Kelowna in April 1937 and a well-attended banquet at the Royal Anne Hotel generated much enthusiasm for the road. The lake had frozen over that year so everyone was keenly aware of the need for an alternative route out of and into town. Volunteers came from all over the valley and as one crew blasted their way through the mountainside, another followed to round out the sharp turns and widen sections so two cars could pass. When volunteers arrived on site in the spring of 1938, they discovered the road had survived the winter and spring runoff and they were able to pick up where they had left off. However, their motivation was severely challenged a few months later when the provincial government announced it would replace the MV Hold-up with a steel-hulled ferry. Still committed to an eastside road and not convinced a new ferry would solve all Kelowna’s transportation problems, a small dedicated group continued to wrestle rocks, brush and trees through summer and into the fall. Then they encountered a large slough at the entrance to Wild Horse Canyon, just as work was wrapping up for the season. It could wait until next year. Progress was being made—a couple more years, they figured, and the road would become a reality.

The MV Pendozi was launched on May 18, 1939. The ferry had been manufactured in Vancouver, dismantled and shipped by rail to Kelowna, and reassembled. The Kelowna dock had already been improved in anticipation and the last corner of the steep hill leading to the Westbank dock had been cut back and widened to make a safer approach. This ferry was different from its predecessor as it could be propelled from either end, so it didn’t have to be turned around before heading across the lake. It also had two lifeboats and enough life-saving equipment for 150 passengers.

Dignitaries came from all over the valley to celebrate the launch of the Pendozi. The Kelowna Board of Trade hosted a lunch at the Royal Anne Hotel for one hundred important people, schools closed early, businesses declared a half-day holiday and over three thousand residents and visitors gathered to watch Mrs. MacPherson, wife of the Minister of Public Works, swung a bottle of champagne against the ferry’s steel hull. The Pendozi, decorated with flags and bunting, was quite a sight as she slid down the slipway and splashed into the lake. It took six weeks of fine tuning and various adjustments before the hourly sailings between 6:00 a.m. and 11:55 p.m. began. Plans to repair the MV Hold-up and keep it in reserve were scuttled when it was discovered the entire bottom of the old boat was rotten and falling apart. The new ferry was a great addition to the Okanagan highway system and everyone rejoiced at how much easier it now was to get from one end of the valley to the other.

The new ferry and the outbreak of war undermined the community’s sense of urgency about the need for the Kelowna to Naramata road. Many volunteers became part of the war effort and interest in completing the project disappeared. The idea has never entirely vanished though: problems getting across the lake often raise the need for an eastside road. In the intervening years, two additional ferries were added to the Kelowna–Westbank service and two bridges have since been built across Okanagan Lake. Though rough vehicle access is available along the east side, only the adventurous actually drive it. The story of a few determined and tenacious pioneers is all that remains of the Kelowna to Naramata road... for the moment.

Always Time to Play

Depression or not, “Canada’s Greatest Water Show,” the Kelowna International Regatta, continued. Competitors from nearby communities joined local athletes and filled in for the visitors and competitors from farther away, who stayed close to home. The Silver Jubilee Regatta of 1931 was notable as war canoe teams from the Growers Co-op and Independent Growers competed in friendly rivalry against each other: this was before they battled out their differences in the packinghouse yards. Youthful athletes competed in swimming, diving, plunging and racing the four-oared shells for the championship of Okanagan Lake.

To celebrate its twenty-fifth anniversary and “arouse extraordinary interest,” the decision was made to hold the Regatta’s first ever queen contest in 1931. The traditional Saturday-night Regatta Parade featured a beautiful yet empty throne, perched on a flatbed truck, with a huge question mark sign balanced on the seat. Then, as the Courier reported, “Kelowna’s pulchritudinous aspirants to the crown and Queen of the Silver Jubilee Regatta” took part in the parade to the “stirring accompaniment of the bag pipes, the gala music of the City Band, and the melodious strains of the Kelownians Orchestra… and gave an optical treat to the large crowd of spectators.”

The evening event began with wrestling and boxing matches, which were to be followed by the crowning of the queen, fireworks and the usual Regatta Ball. The contestant who sold the most tickets would be declared the winner: one ticket equalled fifty votes. Both the Independent Growers and the Co-op Growers joined in and sponsored candidates in the hotly contested event. So hotly contested and complicated that it took so long to count the ballots—the winner received 88,000—that the coronation had to be deferred until the following day. By that time, the Regatta was over and the queen had no chance to reign. The decision was made to hold future queen contests on the first day of the Regatta, to avoid the “farce” the event was in its first year. All was not lost, however, as those attending the ball had an opportunity to win a round trip to Honolulu, Hawaii, a round trip to the 1932 Olympics in Lake Placid, New York, or an electric refrigerator. The winner chose Honolulu.

Neighbouring Communities

Okanagan Mission

Little changed in the communities surrounding Kelowna during the 1930s. A new road to Okanagan Mission was built farther back from the beach and the previous roadway was advertised as an ideal place for Kelowna residents to build summer cabins; lots could be purchased for $150. Electricity arrived in most homes for the first time when West Kootenay Power and Light Company strung in a line over the upper trail from Penticton. The Eldorado Arms began welcoming the public as Countess Bubna’s friends were no longer visiting and its tennis courts were made available to locals. They often stayed for tea. Another oil derrick appeared in the Mission and while many hopeful—or delusional—citizens bought shares in the venture, they were no luckier than those who had invested earlier.

The roof of the Mission packinghouse belonging to the Kelowna Growers Exchange suddenly collapsed under the weight of wet snow in 1937. Before long, a meeting was called to see if there was interest in the community having its own hall. The vote was unanimous and a committee quickly canvassed Rutland and Peachland, which both had their own halls, to see what options were available. When a plan was adopted to build the hall, organizers decided to make it look like a barn and then paint it red to fit into its rural surroundings. Residents offered rough lumber and nails, the Badminton Club donated fifty dollars, the Women’s Institute gave eighty-four dollars and the Okanagan Mission Sports Club gave the hall association just over two acres of land. A plant sale raised a further $30.65, a treasure hunt, $12, while others donated cement mixers and scrapers or offered their services as amateur carpenters. It was a great community effort and less than a year after the packinghouse roof collapsed, over three hundred people attended a dance to officially open the new facility. The building became the area’s social centrepiece and was in constant use for weddings, dances and parties, and even as a schoolhouse and badminton hall. The building is still in use, and the outside was recently returned to its original red after spending too many years in a very solemn grey.

The land adjacent to old Swamp Road was first planted with lettuce and celery in 1932. The damp boggy soil supported the new crop for the next twenty years before it was phased out. Cricket and tennis remained popular in the Mission, though war repeatedly depleted the ranks of those participating. The first horseback riding club in the area started in 1931 with much enthusiasm for paper chases and gymkhanas, which drew riders and spectators from throughout the valley.

Forest fires were a frequent menace and in June 1930 a blaze that burned the hillsides above the community also threatened a number of farms. Twenty years earlier a fire had started at Cedar Creek and decimated the same hillsides. Residents often complained of the valley being full of smoke during the summers as uncontrolled fires were left to burn themselves out. The 2003 Okanagan Park fire burned over the same area again.

Rutland

Rutland residents often discussed incorporating themselves as a municipality, but when that didn’t happen a variety of organizations took over some of the functions of local government. The Rutland Farmers Institute, organized in 1930, explored the possibility of incorporating but got diverted by the pressing need for a pound. Cows and horses were wandering across the roads and through the orchards and becoming both a hazard and a nuisance. Many meetings were held, few decisions were made and no pound was ever created. The organization ceased to exist in the mid-1930s.

The Rutland Parks Society was founded in 1929 by a group of public-spirited citizens who wanted to raise money and buy eight and a half acres for a swimming pool and playing fields. There was great support for the project, and when a child drowned in an irrigation flume the community pulled together and ensured a pool was built for all to use. A paddling pool and a pavilion were subsequently added, and a lifeguard taught swimming. All children under twelve were admitted free, and the facility soon became the community’s most popular summer gathering place.

Grant MacConachie, bush pilot and general manager of Yukon Southern Air Transport, arrived in Kelowna in June 1939 to announce he was putting the city on the province’s air map. An eight-passenger “luxurious air ship” was already providing three scheduled flights a week between Vancouver and Oliver, at the south end of the Okanagan Valley, and he intended to extend the service to Kelowna. Since Kelowna didn’t have a landing strip, the company planned to use the Rutland airfield once it was extended into a neighbouring hayfield. MacConachie urged the community to remove the rocks from the runway as soon as possible so levelling could be done and the service started. While this would only be a “stub line” serviced by a four-passenger plane, Kelowna could expect better service once a site for a more substantial landing strip could be found. Two years later, Yukon Southern Air folded into the newly organized Canadian Pacific Airlines, with MacConachie as its CEO.

Glenmore

The small municipality of Glenmore stuck to its agricultural roots during the Depression. The irrigation systems built during the previous twenty-five years began deteriorating and when the Mill Creek Dam was condemned, construction crews and all their equipment had to travel more than ten miles up the mountain by packhorse to repair it. Then the miles of steel siphon were condemned the following year. The system had been built in 1910 and the inside of the pipe had been given a light coat of paint at the factory. It had begun to rust in its first year and keeping it in working order meant repairmen had to climb into the thirty-two-inch-wide pipe, scrape the inside with wire brushes to remove the rust and reapply two coats of paint. It was a terrible job—and unproductive, as the rust returned almost immediately.

Though Glenmore never had a town centre of its own, it did have a rich social life: the Vagabonds became the community orchestra and played at numerous concerts and dances over many years. The link to Kelowna further tightened when the decision was made to bus Glenmore children into town for school. It was the first school bus service in the area and since there was no such thing as a “school bus,” benches were bolted along the sides of a flatbed truck with a canopy attached overhead. The vacated Glenmore School became the community’s gathering place for many years.

A Gradual Recovery

As challenging as the Depression years were for many in Kelowna, other parts of the country had a much tougher time. Seventy-five carloads of fruit and vegetables left the Okanagan in the autumn of 1936 for the destitute still trying to survive in Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Money from Regina service clubs funded Kelowna’s Prairie Relief Committee and paid for the digging, sacking and loading and for shipping the produce eastward. As the decade grew to a close, farmers and orchardists again realized they needed to find markets beyond the valley and began lobbying for the completion of the Hope–Princeton Highway, which would provide faster travel to Vancouver. Dr. Boyce sold 190 acres of Knox Mountain to the city for one dollar, to become a park. The park formed a natural boundary north of the city limits and the Courier prophesied that “before many years, the new park will be recognized as one of the city’s most precious possessions… and it is entirely possible that before long, a road will be built to the summit and a small terraced lookout will be established.” Twenty-five years later, the Stanley M. Simpson Knox Mountain Trust provided funds to build the road to the summit.

Euphoria swept across Canada in May 1939 as King George VI and his consort Queen Elizabeth began their cross-country tour in Quebec City. After years of bad news, hopelessness and anger the country was ready to celebrate. The royal tour was a perfect excuse, and nowhere more so than in the British bastion of Kelowna. The mayor issued a proclamation to welcome the royal couple, affirming that “They rule in the Hearts of the People… and the citizens of Kelowna, their loyal subjects, rejoice to be honoured with the priceless privilege thus to greet in person the man and woman who so royally and unobtrusively interpret the enduring though intangible ties of Empire… we pledge our unswerving devotion.”

That Their Majesties would get no closer to Kelowna than Revelstoke, about 200 miles away, was irrelevant. Thirteen special railcars filled with Boy Scouts, Cubs, Girl Guides, Brownies, Sea Cadets and ordinary citizens left Kelowna and joined a similar contingent from Vernon. Hundreds of others were more than happy to drive through the pouring rain, over gravel roads at speeds rarely exceeding 30 miles an hour, to get to the celebration. Since the royal train arrived in Revelstoke in the afternoon and required servicing midway through the mountains, most people decided this stop would give them the best opportunity to see the royal couple.

Thousands gathered and happily waited in what the reporters called a “Scotch mist.” The “mist” was unrelenting for awhile and people huddled under umbrellas, blankets, coats and even a roll of tarpaper that suddenly appeared. Seats were at a premium so cushions, blankets, newspapers and apple boxes were pressed into service. The Revelstoke Band, enhanced by a few members from the Kelowna City Band, played alternately with the Vernon Pipe Band. Just before the royal train pulled into the station, both bands played at the same time and the throng of reporters, who arrived just moments before, noted it was a “most noisesome reception.” The din was terrific and the crowd collectively sighed with relief when the bands stopped playing. Then everyone broke into a rousing “God Save the King” as the blue and silver train, with the royal coat of arms emblazoned over its headlight, pulled into the station.

The royal couple mingled freely with the crowd. The king wore the same suit he had worn in the photos published in the Courier Special Edition the week before. The queen, however, wore the most stunning costume of any she had worn since arriving in Canada. It was a deep sky blue and reportedly matched her eyes. The royal couple walked along the railway ties and chatted with children and veterans, and when the crowd broke through the police lines, no one seemed to mind. The couple stayed much beyond their allotted time and the train’s whistle could be heard trying to coax them back aboard to continue on to the next stop. Their loyal subjects were emotionally exhausted when the royals left, but waited patiently for the almost three hours it took the police to get the traffic organized so they could all head home. It had been a joyous celebration.

Canada declared war against Germany in September of 1939. The biggest issue in town at the time was whether Okanagan apples could still be shipped to their traditional British markets. Was there still enough cargo space on the ships travelling the Atlantic? Would Ottawa help market the fruit? Would shipping from Pacific ports and the Panama Canal pay? During the early months no one seemed to think the skirmishes would escalate into war. The Courier reported that merchants were pleased with their “excellent Christmas trade” and noted that “Kelowna was a gay city over the long holidays.”