Chapter One: Before Kelowna

The First Peoples

Long before there was a Kelowna, Indigenous Peoples known as the S-Ookanhkchinx, the Syilx speakers, were a group of the Interior Salish peoples who lived along the shores of the lakes and rivers that flowed into the great Columbia River. These resourceful people followed the seasons as they gathered the roots and berries that grew on the valley floor; hunted elk, deer and small game that flourished in the surrounding hillsides; and traded with neighbouring tribes. Each fall, families would gather for the great harvest of kokanee (land-locked salmon) and smoke their abundant catch before settling in their villages for winter. Theirs was a peaceful, loosely structured society where family took priority.

Horses arrived in North America with the Spaniards in the 1500s when the conquistadores conquered the lands of Mexico and Central America. Large herds of mustangs flourished during the following years as nomadic Mexicans and Native Americans travelled the southwest. The offspring of the original Spanish horses made their way northward by the 1700s and transformed the methods of travel and trade patterns of the aboriginal residents of the Okanagan Valley region. Yet when winters were severe, the horses became an emergency source of food, so herds never became large. When the fur brigades began passing through the Okanagan in the early 1800s, they bought or traded for the Natives’ horses.

In these early years, the word “Okanagan” appeared in many forms. Its origins seem to be in the Syilx language: “S-Ookanhkchinx” means “transport toward the head or top end.” The earliest inhabitants of the valley travelled northward from the great Columbia River basin, along its tributary, the Okanogan River, and continued past the chain of lakes that dot the valley floor. Once they reached the south end of Okanagan Lake, they continued northward to the head of the lake. These lakes and rivers defined the traditional territories and transportation routes of the Syilx people. In 1811, David Thompson wrote of the Oachenawaw people; the following year he referred to the Ookenaw-kane. Other early records note about thirty-five variations of the name, including the Oakinnackin, the O’kanies-kanies, the Oukinegans and the O-kan-a-kan.

The local people also worked as guides and sometimes traded pelts with passing traders, though the valley was never a primary source of furs. Relations between the Interior Salish and the Europeans were friendly in the early days, as colonial Governor James Douglas promised the rights of the Native people would be equal to those of the new settlers. The Indigenous tribes’ traditional nomadic lives gradually transformed into more permanent settlements as they began cultivating the land, though they continued to fish their historic streams and graze their cattle on traditional ranges.

The federal and provincial government established Indian Reserves in the Okanagan during the late 1800s and early 1900s, though they were subsequently reduced in size by a 1916 Royal Commission. The Okanagan Nation reserves at the time included lands from the north end of Okanagan Lake, near Vernon, through the Central Okanagan. In spite of being adjacent to the lakeshore, the reserves near the present-day West Kelowna were seen to have little value as they lacked a source of water.

As more settlers arrived, reserve lands were increasingly encroached upon and the Indigenous people gradually lost access to their traditional water sources and the newly designated Crown grazing lands. Land use became even more insecure with the enactment of the federal Indian Act in 1876. The government’s policy of assimilation, the arrival of foreign religions and the residential school system soon diminished and marginalized the once-proud and self-sufficient Okanagans.

Western Exploration

Early exploration in northern and western North America mostly occurred as a result of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company (the Nor’Westers) trying to outdo each other in finding a Pacific port, in order to ship their furs to the Orient and Europe more quickly. Alexander Mackenzie, a Nor’Wester, went in search of the Pacific Ocean in 1789, only to end up on the shores of the Arctic Ocean. After returning to Britain to sharpen his skills, Mackenzie came back in 1792 and this time followed the Peace River to the soon-to-be-named Fraser River. Hearing its downstream waters were unnavigable, he diverted westward to a Native trading route over the Coast Mountains, where he was halted by the hostile Heiltsuk people at Bella Coola on an inlet along the Pacific Coast. He soon realized it wasn’t a viable port, though he did achieve the distinction of making the first recorded crossing of the North American continent, north of Mexico.

Mackenzie and Captain George Vancouver missed each other by a mere two months, as the captain and his crew had recently arrived at the inlet as part of their survey of the west coast. Mackenzie’s failure to find a Pacific port left the earlier shipping routes unchanged: the Hudson’s Bay Company shipped from York Factory on Hudson Bay and the North West Company shipped from Montreal. Both routes were lengthy, arduous and fraught with enormous challenges.

The Rocky Mountains remained a formidable barrier to the Pacific Ocean and most of the early exploration of Canada’s western territories was made along its north–south flowing rivers. Simon Fraser, another Nor’Wester, picked up where Mackenzie left off when he was sent to take charge of the area west of the Rockies in 1805. In spite of the aboriginal tribes in the area warning that the river was impassible and the portages worse, Fraser set off southward in 1808 along what he was sure was the Columbia River. Thirteen days later the canoes were abandoned, and Fraser and his crew proceeded on foot along the treacherous river until eventually reaching the Strait of Georgia. They were driven back inland by hostile Natives and Fraser soon realized the river that would later bear his name was not the Columbia. The journey also revealed the river’s largest tributary, the Thompson River, which Fraser named after his friend and colleague, David Thompson. This new discovery provided access inland—and to the area that was soon to be known as the Okanagan Valley.

Discovering a Pacific Port

In the late 1700s, American businessman John Jacob Astor and his Pacific Fur Company joined with the North West Company, and together they became a formidable competitor of the Hudson’s Bay Company. The elusive Pacific port was everyone’s priority. Scotsman David Stuart, a Nor’Wester, boarded the Tonquin, an American merchant ship owned by Astor, in New York harbour in September 1810, heading for the west coast of North America via the Falkland Islands and Cape Horn, off the tip of South America. The ship arrived at the mouth of the Columbia River six months later, and fought its way upstream through fifteen miles of sandbars to where the crew would build Fort Astoria (named after John Jacob Astor). Two months later, another Scot, David Thompson, also a Nor’Wester who had been charged with finding an overland route to a Pacific port, arrived at the partly constructed fort.

Later in the summer of 1811, Stuart and Thompson left Fort Astoria by canoe and travelled up the Columbia River until they reached the mouth of the Okanogan River. Stuart and his small party headed a half mile upstream, where they built Fort Okanogan, as Thompson continued along the Columbia, eventually arriving back in Montreal in 1812.

The Okanagan Valley is unique in the annals of Canadian exploration as it was discovered from the south, by Scottish explorers employed by an American. David Stuart proceeded up the Okanogan River, along the aboriginal trails skirting the Okanagan lakes, and continued northward until he reached Cumloops. He overwintered there before returning to Fort Okanogan the following year. Cumloops, soon to become Fort Kamloops, was built at the confluence of the North and South Thompson Rivers. It was David Stuart’s journey north from Fort Astoria that finally revealed the elusive connection between Canada’s north and the Pacific Ocean. The route was soon to become a vital link in the lucrative North American fur trade.

For the Sake of a Hat: The Okanagan Fur Brigade Trail

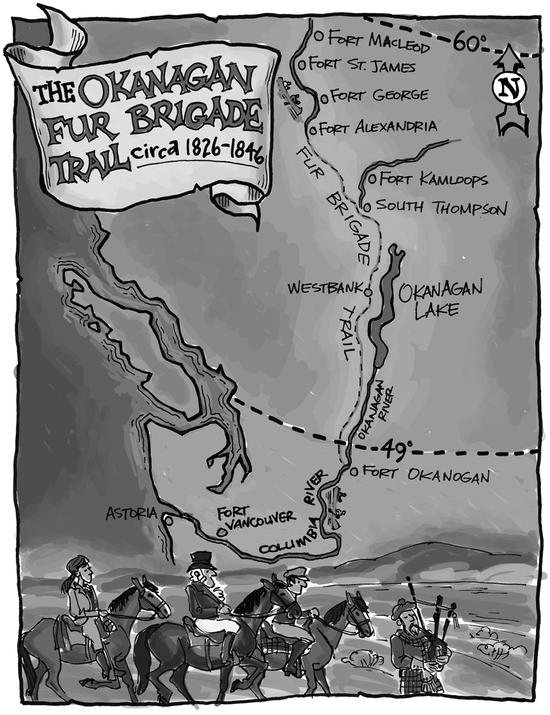

It took a few years to sort out whether the Okanagan Valley really did provide a better route for getting northern furs to market and vital supplies to the remote forts. Some years the fur brigades travelled through the Okanagan Valley to Fort Astoria, while in other years the furs were shipped overland and took months to reach the eastern ports. Competition was fierce, and in 1821 the Hudson’s Bay Company absorbed the North West Company, and the governor of the combined company, Sir George Simpson, came west to look over the company’s shipping options. The logic of the southern route quickly became apparent, and from 1826 until 1847 fur brigades regularly travelled the Okanagan Trail.

Furs were collected from the various forts on the northern tributaries of the Fraser River and transported by canoe to Fort Alexandria, near present-day Quesnel. Since the Fraser was not navigable south of the fort, the furs were transferred to pack horses and successive brigades of two or three hundred horses headed south. Fresh pack horses were picked up halfway along the route at Fort Kamloops, and the brigades continued on through the Okanagan Valley and along the Okanagan River to Fort Okanogan. Once they arrived, the furs were again loaded into canoes for their journey to Fort Vancouver (near present-day Vancouver, Washington), the new outpost established by Simpson in 1824 a few miles upriver from Fort Astoria, on the Columbia’s more accessible northern bank. There they would be loaded on ships bound for Europe. The distance from Fort Vancouver to Fort St. James, the brigades’ northern terminus, was approximately 1,200 miles and the journey would take about two months to complete. The brigades would usually spend a month in Fort Okanogan collecting supplies and trade goods before returning north.

Bagpipes reverberated across the hillsides as the brigade travelled the length of the Okanagan Valley. It must have been quite a sight: a long line of pack horses and their handlers, led by the distinguished-looking chief factor, or head trader, in his high beaver hat, a stiff white collar that reached to his ears and a finely tailored black jacket. Ceremony was essential and bagpipes set the stage for the gunfire salutes that marked entering and departing from forts or campsites. The day’s routine rarely varied: the campfires were lit at the first morning light and breakfast, usually dried salmon, was prepared for all. The scouts departed first to find the next night’s campsite, while the brigade horses were rounded up and each reloaded with two eighty-four-pound packs of furs and camp supplies. The brigade broke camp about nine a.m. and by four that afternoon, having travelled about twenty miles, they would arrive at the new campsite. The factor’s tent was always the first to be erected, set apart from the others, and his fire was the first to be lit.

The agreement signed between Britain and the United States in 1846 establishing the forty-ninth parallel as the international boundary restricted the brigade’s access to Fort Vancouver, and brought an end to the Okanagan Fur Brigade Trail. Governor Simpson had foreseen the possibility of Fort Vancouver being lost to the British and had already established Fort Langley, on the south side of the Fraser River, as an alternative port. The Hudson’s Bay Company and the fur trade remained part of the west for another twenty-five years, although the demand for pelts decreased as fashionable Europeans lost interest in fur, and aboriginal communities became less nomadic as they turned to farming and raising cattle.

Today, a map showing remnants of the Okanagan Brigade Trail is available to the curious who want to search it out along Westside Road, across Okanagan Lake from Kelowna. Part of the trail is on private land—some has been built on or planted—while other sections have vanished. Occasionally a marker will appear on a tree, identifying the “H.B.C. Fur Brigade Trail.” In West Kelowna, at the intersection of Highway 97 and Old Okanagan Highway, a cairn marks the high point of land were the local Indigenous Peoples and the brigade traders carried on their business. Otherwise, there is little evidence of the Okanagan’s short-lived involvement in Canada’s fur industry.

God Followed

By the time the last of the fur brigades passed through the Okanagan in 1847, Protestant missionaries were already well established in the Oregon territories. The Catholic Church needed a presence in the new land but was so short of priests that it had to appeal to France for assistance. Twenty-four-year-old Charles John Felix Adolph Pandosy was part of a small group of Oblates who left their motherhouse near Marseilles in 1847 and sailed to the New World.

Pandosy was from a prosperous landowning family in Provence, yet took vows of poverty and devotion when he joined the Oblates of Mary Immaculate (OMI). An unlikely candidate for mission work, the young man had excelled in Latin and French literature and was recognized for his beautiful singing voice. Pandosy, however, wanted more than a cloistered life and welcomed the opportunity to venture off to an unknown world. Once in New York, the small party of Oblates joined a wagon train and travelled across the sparsely populated continent to Fort Walla Walla, in present-day Washington state.

Pandosy was soon ordained and became known as Father Charles Marie Pandosy OMI. The young priest worked and lived among the Yakama tribe, where he learned their language and taught them to plant and harvest, and then baptized them into his church. He could not have anticipated such a life: there were few comforts, he lived with loneliness and isolation, and he persevered through immense hardship. It wasn’t long before hostilities escalated as settlers thought he was siding with the Yakamas and the Yakamas thought he was aiding and abetting the settlers. Militias were sent in to protect the newcomers and soon local wars escalated into massacres as both sides fought to the death. It became impossible for Father Pandosy and his colleagues to remain in the American territories.

The Washington missionaries were called to Esquimalt on Vancouver Island in the summer of 1858. Pandosy stayed for the winter and began planning to start anew in the colony of British Columbia. The young priest briefly returned to Colville, just across the American border, in the spring to gather supplies and find settlers who were willing to join him in establishing a new mission in the Okanagan Valley. Cyprienne and Theodor Laurence, French Canadian brothers who had been involved in the fur trade, and Cyprienne’s wife, Therese, from the Flathead Indian Reservation, agreed to accompany him, as did an unnamed Flathead man who was so devoted to Father Pandosy that he and his wife decided to follow the priest to the new land. William Peon (or Pion), a Sandwich (Hawaiian) Islander, one of many who made their way to the west coast on the sailing ships that reprovisioned on the islands, agreed to pack the small party into the Okanagan Valley.

Following the Okanagan Fur Brigade Trail across the new international border, Pandosy and his party made their way northward until they reached the Native village at the south end of Okanagan Lake. Once there, Therese was called upon to convince her uncle, Chief Capot Blanc, and the other chiefs from the area that the priest and her husband intended to help improve the Natives’ condition and should be allowed to settle their valley. The Hudson’s Bay Company had rarely encouraged settlement, and the traders and trappers who had previously passed through the valley hadn’t created a problem for local aboriginal groups. Settlers, however, were another matter, and those who had arrived earlier with the idea of staying had been threatened by the chiefs and ordered to move on. Therese, perhaps as an enticement, added that if the chiefs did not agree to her request or harmed her companions, her uncle, Capot Blanc, would have to accept responsibility for her care. It took a few days, but she prevailed.

Instead of following the established trail, the party chose to travel along the rocky, mountainous east side of Okanagan Lake. The route took them through the “Grand Canyon”—likely Wild Horse Canyon—and onward to the south end of Duck Lake (near Winfield today). Father Pandosy and his party arrived in the fall of 1859 and declared they had at last reached the site of his new mission. The winter was bitterly cold and the snow was uncommonly deep. Game was scarce, and with no time to build shelter or gather provisions, the party lived in tents, slaughtered their horses for food and survived on the diet of the local peoples: berries and roots, baked mosses and native teas.

When spring arrived, the area proved too marshy and the group moved to higher ground for the summer and scouted around for a more suitable permanent site. They eventually discovered a broad sweep of flat land a few miles south, near a creek that would soon be known as Mission Creek, and quickly determined that the surrounding land would better meet their needs. Not wanting to spend another winter in tents, the men quickly built a small log house with a church on the ground floor and sleeping quarters above. The Mission of the Immaculate Conception became a reality on the site they called L’Anse au Sable, or Sandy Cove.

The wider area became known as the Mission Valley, after Father Pandosy’s Mission at L’Anse au Sable—though many thought “Sandy Cove” referred to the mouth of Mission Creek, not the Mission itself. The settlement had been established at about the midpoint of Okanagan Lake, and the settlers soon noticed that the tillable land surrounding the Mission, and to the north and south, was immense. In a letter to his superiors in France, Father Pandosy wrote that this was the largest valley that could be cultivated in the surrounding countryside, saying, “All who know it, praise it.” By the early 1900s, the area became known as the Okanagan Valley.

Soon after Father Pandosy settled, Father Pierre Richard (1826–1907), who had also been in Esquimalt, arrived in the valley for the first of what became a succession of visits. He stayed for varying periods of time and was known as the more practical of the two priests: Father Pandosy taught the Natives to speak French, play musical instruments and sing their Latin masses with such beauty they rivalled the choirs of the great cathedrals of France. Father Richard taught them to build fences, plant fruit trees and a vineyard, and grow the ground crops that would sustain them. In November 1860, Father Richard filed a rural pre-emption claim for the Mission on the Great Lake, noting that the river of L’Anse au Sable was to the south.

The missionaries soon had considerable success converting and ministering to their flock: in just the two years after the Mission was founded, they baptized 121 persons. Father Pandosy worked in the fields, devised ways to irrigate his crops and built a root cellar to store their harvest. A brothers’ house was added to the site in 1865 to house the succession of priests who stayed at the Mission, along with those travelling through the area. The following year, a log barn was added to the site. In 1882 a new sawn lumber church was built, which featured five Gothic-inspired windows on each side of the nave and a bell tower.

During these years, Father Pandosy was sent to various other missions around the province, sometimes for two or three years at a time, but he always returned to his home at Okanagan Mission. In February 1891, Pandosy was called to Keremeos to give final rites to a dying parishioner. It was fiercely cold but he was undeterred as he walked through the drifting snow—he had travelled the route several times before, though he was now sixty-seven years old and in somewhat tentative health. After leaving Keremeos, he made it back as far as Penticton, where he was taken in by Chief Francoise of the Penticton Indian Band, as he had become seriously ill. Recognizing the priest’s perilous condition, the chief sent for Mrs. Ellis—the wife of Tom Ellis, one of the area’s cattle barons—who was known for her nursing skills. Little could be done and Father Charles Pandosy died on February 6, 1891. He was returned to his Mission on the steamer Penticton and buried across the road from his church.

While the Okanagan Mission benefitted from the presence of many priests during its forty-two-year existence, none have been identified as strongly with the place and its history as Father Pandosy. Most of those who served were devout and passionate men who felt they were called by their God to go forth to save, educate and minister to Indigenous people in the New World. They were true pioneers who suffered privations beyond our present-day comprehension: they were frequently close to starvation, often isolated and lonely, and knew few creature comforts. Clothing, blankets and seeds were hard to come by, and most went barefoot and bare-headed in the summer and used pelts and hides to survive the winters. They worked constantly, walking to their destinations, which were often over the next mountain range or two. Though their physical and mental well-being concerned their superiors, most priests were on their own to make the best of whatever was available. Their abiding faith carried them when little else was available.

The Mission and the community around it continued to flourish after Pandosy’s death. The farm grew to about 2,450 acres, and the Mission became the Catholic Church’s headquarters for the area from the international border in the south to Fort Kamloops in the north, the Similkameen Valley in the east to the Nicola Valley and Merritt in the west. When the Canadian Pacific Railway completed its transcontinental line in 1885, however, Kamloops became the nearest rail connection. The Oblates moved their headquarters to the St. Louis Mission in Kamloops in 1895. The Okanagan Mission and all related properties were sold to Father Eumelin and other members of his family in 1896. Though Eumelin was not an Oblate, he continued to run the Mission as its priest until 1902, when the original Mission of the Immaculate Conception was officially closed. The land was purchased by the Kelowna Land and Orchard Company in 1906, then subdivided and sold as prime orchard sites.

Gold Everywhere

The Hudson’s Bay Company had been buying gold from the Okanagans for many years, though David Douglas was the first to record its discovery in 1833. Douglas, a Scottish botanist, was collecting specimens for the Royal Horticultural Society while travelling through the area with one of the company’s fur brigades. The Hudson’s Bay Company was in the fur business and wasn’t interested in having its lucrative trade disrupted by an influx of unruly miners: it kept Douglas’s discoveries to itself for many years.

Gold was discovered in California in 1848. Over the next seven years the hopeful, the delusional, the skilled and the ill-equipped converged from all over the world to pan the rivers, creeks and gullies for the magical metal. As it became harder to find and mining became more technical and more costly, word of gold discoveries in British Columbia drifted south and enticed miners to leave for the British territory. First there was gold in the creeks near Kamloops, then Bear Creek on the west side of Okanagan Lake, and then Mission Creek, Rock Creek and the Fraser River. By 1858, amid turmoil and lawlessness, over thirty thousand miners had moved into British territory—and they fought with the Natives and each other to stake their claims.

The chaos also brought opportunity as the newcomers needed to be fed and supplied. An uneasy truce was negotiated that same year with various Washington tribes, which allowed the Palmer and Miller wagon train to leave Oregon and make its way through the Okanagan Valley to the Cariboo goldfields. Miller, an adventurer, and Palmer, an experienced wagon captain and treaty negotiator, were accompanied by two hundred miners who were fearful the truce wouldn’t hold and wanted the security of travelling in a convoy. Ox teams pulled nine wagons loaded with food, equipment and clothing to sell to miners. Once through the Washington Territory, they picked up the Okanagan Fur Brigade Trail and headed north. One wagon loaded with sugar overturned crossing the Columbia River, and another was lost farther along the trail, but the remaining seven crossed the international boundary and continued along the old brigade trail to Deep Creek, near present-day Peachland, on the west side of Okanagan Lake.

Stalled by the rough shoreline and the ravines that ran down to the lake, the group had to find another way to continue northward. Undaunted, they felled trees and lashed them together into rafts—some reports say fifty logs were needed for each one. The wagons were dismantled and loaded onto the rafts, piece by piece, along with all the goods they were carrying, and paddled across the lake to the flat eastern shore. After they landed the wagons were reassembled and reloaded, and then everyone waited for the cattle and horses that had backtracked to the south end of Okanagan Lake to be rerouted down the eastern shore. Once they were all back together, the wagon train continued on to Fort Kamloops.

This was challenging travel. Each wagon carried about three thousand pounds of provisions and merchandise for sale to miners, and when the terrain became too rough, the wagons were once again disassembled and the goods transferred onto the horses and oxen. As the countryside flattened out, the wagons were again reassembled and reloaded and the journey continued. When the group finally arrived in Kamloops, the wagon masters heard the terrain to the north was even more challenging and it made little sense to continue on. The Cariboo was still a long way off, but Palmer and Miller and the other wagoneers found a needy and hungry market at the fort and were able to sell everything for a great profit, including their oxen, which were soon seen roasting over open fires. Normally sustained by the wild meat they shot or trapped along the trail, the hungry miners were overwhelmed by the prospect of so much tame meat: they devoured the animals without giving much thought to what other uses the beasts might have been put to. So great was the impression created by this first wagon train that tales of its size and its troubles were told and retold in Native villages for many years.

Cattlemen from Washington and Oregon used the Okanagan as a supply route to the Fraser River and the Cariboo goldfields for a few more years, but settlement didn’t come quickly to the Okanagan, as the valley was still isolated and access was difficult. However, the new colonial government in Victoria was becoming increasingly alarmed by the number of Americans crossing the international boundary and making their way into the southern and eastern parts of the province. Gold was being discovered, mines were being built and the new government needed the revenue and soon established its own tax collectors in the area. The Fraser River sternwheelers carried government agents, settlers and supplies as far inland as Hope, but only a narrow foot trail continued on to the Southern Interior.

By 1860, Edgar Dewdney, a British engineer, was commissioned to build a wagon road from Hope through to the goldfields in the Kootenays. The existing footpath was converted into a four-foot-wide trail, wide enough for a pack train, and cut through to Vermillion Forks (Princeton). Then the contract ended and nothing happened for four years. Finally, Dewdney was commissioned to pick up where he had left off and continue the trail along the Similkameen River to Keremeos, and over what would become Richter Pass, to Osoyoos. The trail, soon known as the Dewdney Trail, continued on for another three hundred miles and eventually reached Fernie and the coal fields awaiting the arrival of the Canadian Pacific’s transcontinental trains.

The Dewdney Trail, or Hope Trail, also provided access from the Lower Mainland to the Mission Valley. Pack trains carried the ordinary and the extraordinary, settlers rode and walked, and Father Pandosy travelled back and forth many times as the Okanagan’s first pianos and billiard tables were hauled over the pack trail. Riders on horseback strapped mail pouches to their saddles, prospectors followed the latest rumours of gold discoveries and cattle barons drove their herds from the Interior over the trail to the port of New Westminster. The famous also used the trail: American General William Tecumseh Sherman travelled from Osoyoos to Hope in 1883 with a military escort of sixty men, and Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria travelled over the trail to the Similkameen in search of bighorn sheep before his 1914 assassination, the event that triggered World War I. The remarkable engineering of the Dewdney Trail established the first route into the Okanagan from the Lower Mainland of BC.

Feeding the Influx

There were more cattle in Oregon than buyers and Palmer and Miller’s expedition encouraged ranchers to look north to sell their stock. Soon a succession of cattle drives followed the old brigade trail through the Okanagan and continued on to the Cariboo goldfields. Attempting to collect all the revenue due them, the colonial government levied taxes of a dollar a head at Kamloops, or drovers could pay a one-time fee to cover them for a six-month period. Yet the government was aware there were too few cattle in the British territory to feed the miners. Not wanting to deal with a food shortage, government representatives were known to turn a blind eye to those who slipped past the forts. It wasn’t long before cattle began overwintering on the abundant bunch grass ranges along the Thompson River, near the fort at Kamloops, waiting to be driven to the Cariboo when the trail re-opened in the spring.

Old Hudson’s Bay men and drovers who knew the land began pre-empting the ranges along the Thompson River in the early 1860s, and settling in the area. About the same time, the Vernon brothers arrived from Ireland in search of gold, and a man named Cornelius O’Keefe decided he could make more money raising cattle instead of driving them from Oregon. All pre-empted large acreages in the North Okanagan. As mines developed in the Boundary and Kootenay areas, Thomas Ellis, another Irishman, and J.C. Haynes, a customs officer who took payment in cattle when the drovers didn’t have the cash, accumulated even larger acreages in the South Okanagan. The settlement around Father Pandosy’s Mission was at the midpoint of the valley, and farther from the gold discoveries and the mining boom; it received little benefit from the activity going on to the north and to the south. Most of those who settled around the Mission were subsistence farmers, though some also ran herds of cattle on the bunch grass hillsides and sold their stock to miners passing through the area.

When the Cariboo’s gold was mined out, the number of men working claims also diminished, and the demand for beef and other provisions disappeared. Those settlers who retained remnants of their once-large herds took great interest in discussions about the colony of British Columbia becoming part of the Canadian Confederation. Of even greater interest was the promise of a railway that would join British Columbia with Eastern Canada. Construction was rumoured to be starting within two years. In addition to feeding the construction crews, ranchers could use the rail line to deliver cattle to the Cariboo and the Kootenays. On the strength of the promised railway, British Columbia joined Canada in 1871.

In the meantime, the once-abundant bunch grass ranges of the Okanagan were over-grazed, and many ranchers had little choice but to become subsistence farmers, though the entrepreneurs among them opened trading posts, became postmasters or started up sawmills or grist mills. Those with connections ran for public office or were appointed to government positions. Few had any cash to buy additional land, even at a dollar an acre, and those with cattle used nearby Crown ranges as their herds began to grow. The winter of 1879–80 was unusually severe, and when thousands of cattle starved to death, ranchers realized they needed to grow hay to prevent such catastrophes from happening in the future. It wasn’t long before the valley’s bottomlands were transformed from range to hayfields.

The long-awaited construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway finally got underway in early 1880. The chosen route through the Kicking Horse Pass and Kamloops set the stage for a dramatic turnaround in the Okanagan cattle business. Five thousand men constructed the line between Yale and Savona (about 175 miles) and the demand for beef was so great that even the large syndicates—the Douglas Lake Cattle Company in the Nicola Valley and the British Columbia Cattle Company in the South Okanagan—couldn’t meet the railway’s demand for beef. Cattle sales provided the ranchers with the cash needed to buy land; the large O’Keefe and Coldstream ranches in the North Okanagan and the Lequime, Knox and Postill ranches in the Mission Valley grew to many thousands of acres. The railway also brought settlers to the Prairies, and then took BC cattle eastward to feed them. Some Okanagan ranchers saw an opportunity closer to home and opened their own butcher shops in the Lower Mainland to provide for the growing number of settlers heading west. The Okanagan was transformed into wide-open rangeland where large herds of cattle thrived on the luxurious bunch grass that covered the valley’s hillsides and bottomlands.

And, Finally, Settlers

The Americans always coveted Southern BC. Even after the international boundary was established in 1846, many maintained that the British part of the Columbia District—the land between Oregon and Alaska—was still rightfully part of their Oregon Territory. It didn’t take long for those in BC’s colonial government to realize they needed settlers in the Okanagan and the Kootenays. To ensure the land stayed in British hands, British citizens could pre-empt 160 acres of land by 1860. Some registered their land, stayed to work their property and quietly became part of the growing community. Others claimed land but moved on, and those who followed claimed the same property. Some just squatted on the land or made minor improvements, then moved on and left little or no trace of their presence.

Many of those passing through the Mission Valley commented on the poverty of those trying to eke out a living there. With few exceptions, the houses were small and poorly constructed—one leather-hinged door and two small windows, perhaps filled in with glass brought by pack train, or just thinly scraped hides. There was little opportunity to sell what was grown, so most settlers only grew or raised what their family needed. Yet with Father Pandosy as the founding force behind the new Mission and his French Oblate order supporting his endeavours, French-speaking settlers from both Quebec and France were drawn to the Mission Valley. French was the language of instruction at the school as well. Many details of these early settlers have been lost to time but names such as Laurence, Christien, Boucherie and Bouvette continue to resonate locally. Others left a more substantial record.

First, the Lequimes

Eli Lequime and his wife, Marie Louise, were among the first to settle near Father Pandosy’s Mission. Eventually, Eli would become known as “King of the Mission Valley.” He cleared the land and created a substantial and productive farm: his cattle herds grew and he built the area’s first trading post, hotel and saloon, sawmill and grist mill. The Lequime homestead served as the social and economic heart of the Mission community for many years.

Eli was born in France and ran away to sea in 1825, when he was fourteen years old. He travelled the world for nearly three decades and then arrived in San Francisco in 1852, when so many of the hopeful from around the world were flocking to California to search for gold. Eli staked his claims and persevered for a couple of years, but finally gave up and returned to join the French forces on the Russian front during the Crimean War. Returning to France from the battlefield, Eli met Marie Louise Altabagoethe, the woman who would eventually become his wife. Eli left France again soon after and by 1856 was back in San Francisco running the city’s first French hand laundry. Marie Louise followed, and they married and moved to Marysville, California, a declining gold town, where they ran a successful saloon for the next three years. As gold was becoming harder to find, rumours began filtering south about new discoveries in British Columbia.

Eli, Marie Louise and their two-year-old son Bernard boarded a Spanish ship in San Francisco and travelled for five days before disembarking in Victoria. They caught another boat to the mainland, joined a pack train and travelled to Fort Hope, where their second son, Gaston, was born. They stayed at Hope and panned for gold for the next two years. Then gold was discovered in Rock Creek on the Kettle River, west of Osoyoos near the US border, and it didn’t take long for the Lequime family to decamp and move on. With their two young children tied in panniers on the back of an ox, the couple walked 175 miles to the new hotspot. Deciding there was more money to be made catering to the miners than panning for the elusive mineral, the couple opened a trading post and saloon.

Within a year, that boom also went bust. The family packed up, yet again, and began walking to the Cariboo, 300 miles away. Rock Creek had been a tumultuous time for the family: Gaston, at two years of age, had fallen into a miner’s sluice box and drowned; Bernard had been kidnapped by a curious Native, though he was returned home after a couple of days; and another son, also named Gaston, was born. Father Pandosy discovered the family on the trail: the parents were walking, their belongings tied onto their horse, and the children rode the family’s cow. Always looking for more settlers, Pandosy convinced the Lequimes to settle in the Okanagan instead of continuing on to the Cariboo.

In 1861, Eli registered a land claim northeast of the Mission; the site was noted to have good soil, ample water and many trees. After building their first house, a fourteen-by-twenty-foot log cabin with a dirt floor and roof, Eli opened a trading post next door. Marie Louise was known for her firm hand and sympathetic heart and ran the store for many years. She was a big woman and seemed undaunted by the rough, wild and unforgiving country that surrounded her. With few other women nearby for company, she raised her children, ran the store and doctored lonely souls stricken with smallpox, mountain fever, broken bones, broken hearts or fallout from the latest barroom brawl.

Their nearest competitor was a trading post in Fort Kamloops, 110 miles away, and the Lequimes’ business thrived. Eli’s merchandise came by wagon train from Walla Walla, Washington, crossing the international boundary near Yahk, in the Kootenays, and travelling on to the Okanagan. As the trails improved and Hope was only eight travelling days away, Lequime’s thirty- to forty-horse pack trains would travel to Hope four or five times a year to stock up on goods for his store. Once a year, Eli would continue on to Victoria to buy fancy goods and replenish his own library.

The Lequime trading post became the business and social hub of the Mission Valley. Trappers traded furs and Eli kept a well-calibrated scale on his office desk for the miners who wanted to exchange gold dust for food and supplies. While some things were in short supply, whisky wasn’t one of them, and a still is known to have been on the site from the mid-1860s on. Try as they might, the priests couldn’t convince those attending Mass in the morning that there was an alternative to the gambling, horse races and drinking that filled the rest of their day. By sundown, the morning’s congregants were often roaring drunk and many would have gambled away their most precious possessions.

The Lequimes had two more children while they lived near the Mission: a daughter, Aminade, in 1866 and another son, Leon, in 1870. Eli and Marie Louise were among the most worldly of the French settlers in the area, and looked forward to the monthly arrival of the mail, including the newspaper Le Courier, from San Francisco. Bernard was sent to school in New Westminster at the age of twelve and then on to Victoria to learn carpentry before returning to the valley. The Lequime family ran over 1,300 head of cattle on two thousand acres of valley bottom land and used an additional six thousand acres of rangeland on the upper benches. Their hotel was the first in the area and the only stopping-off place for many years. When the Okanagan Mission post office opened in 1872, Eli was appointed its first postmaster and remained in that position until he left the valley. Bernard, his son, succeeded him.

Eli had lived in the Mission Valley for twenty-seven years when he decided, at seventy years of age, that it was time to return to civilization. He had begun with almost nothing, and amassed a fortune far greater than anyone else in the area. He had created jobs for others and financed many who needed money to get started. Life in the Mission Valley wasn’t easy and many moved on, but Eli and Marie Louise had stayed, worked hard and created an empire. They sold it to their sons, Bernard, Gaston and Leon. Eli moved to San Francisco in 1888, along with his daughter, Aminade, and Gaston’s two-year-old daughter Dorothy. (Gaston had married Marie Louise Gillard, niece of another pioneer, but he died in 1889 as a result of an unfortunate encounter with a steer during a cattle drive.) Eli’s wife, Marie Louise, left the Okanagan a year or two later and joined Eli, her daughter and her granddaughter in San Francisco. She died there in 1908, ten years after Eli passed away. The two remaining brothers continued to run the Lequime family businesses: Bernard was the operational and financial partner, while Leon looked after the family’s cattle business.

Gillard and Blondeaux: An Unruly Pair

Auguste Gillard and his mining partner, Jules Blondeaux, met Father Pandosy in Hope in 1862 when the priest was collecting his mail and supplies. He convinced the pair to join his Mission community. The two were among the many who had left France in the 1850s in search of gold, and had panned the creeks and gravel beds of California. When they heard rumours about the discovery of gold in British Columbia, they boarded a Spanish ship in San Francisco and arrived in New Westminster a few days later. From there, they headed to Boston Bar, where they dug ditches and built sluice boxes, but then Gillard got into a fight with a local Native, and the two decided they’d better get out of town before word got around that the man was dead.

Once they arrived in the Mission Valley, each man pre-empted 320 acres, with Gillard’s acreage extending from the foot of Knox Mountain in the north to Mill Creek in the south, and Richter Street in the east to the lakeshore in the west. Some years later, this pre-emption would become the Kelowna townsite. Blondeaux’s pre-emption encircled his partner’s, extending to the north and east, and would also be incorporated into the early Kelowna townsite some years later.

Blondeaux soon sold out and returned to France, yet Gillard remained in the area. He never married, and in spite of the missionaries’ efforts he spent much of his time betting on the horses, drinking too much and gambling away his possessions—the last of which was his land, which he sold to Bernard Lequime in 1890. Letters addressed to his sweetheart in France, assuring her of his impending return, were found on his deathbed in 1898. He died poor, and alone, and still in the Mission Valley.

A.B. Knox, the Cattleman

Arthur Booth Knox was either a vengeful arsonist or the victim of a serious miscarriage of justice, depending on whose side you were on. Knox was a Scot who arrived in the Mission Valley in 1874 from the Cariboo goldfields. He bought the land once owned by Jules Blondeaux and expanded it to include the lakeshore property that became known as Manhattan Beach. There he built a driving shed, a warehouse capable of storing the many tons of wheat grown on his farm, and a wharf—where, in time, the wheat would be picked up by sternwheeler for shipment out of the valley.

At some point, Knox increased his holdings to include the mountain that now bears his name and a substantial part of the Glenmore Valley, which ran north to what is now Okanagan Centre and parts of Winfield. He farmed his land for over twenty years, and ran over 1,700 head of cattle and 50 horses. When the Kelowna townsite was laid out, he built a fence along its eastern boundary to keep his cattle from wandering onto Bernard Avenue, the town’s main street.

The Mission Valley was becoming over-grazed by the 1890s, and the abundant bunch grass that had supported the earlier cattle drives was being replaced by hayfields. About this time, Tom Ellis, the biggest cattle baron in the South Okanagan, arrived in the Mission Valley and bought one of the financially troubled pioneer ranches. The locals were suspicious of this interloper and his motives, and what other farms he was going to take over. Ellis’s new ranch had three stacks of premium and scarce timothy hay in the yard awaiting the arrival of his cattle from Penticton: they were being brought in to overwinter. A second herd arrived in early January 1891, and when the farm manager wandered out to the yard shortly after their arrival, two stacks of the hay had already burned to the ground and the third was well on its way. The flames were seen all over the valley, and while there were various suspects, Arthur Booth Knox was charged with arson. A battle of the cattle barons ensued. Ellis owned huge amounts of land, was an influential man with a forceful personality and, as a magistrate, was well known throughout the province. Knox also owned a lot of land, but he was a quiet, unassuming loner who was only known by his friends and neighbours.

The ensuing court case was heard in a Vernon schoolhouse and it became a legendary battle. Ellis posted a $250 reward—huge for the time—for the conviction of the arsonist. Witnesses were bought and bought off by both sides. Henry Bloom, one of Knox’s employees, claimed the reward saying Knox had offered him money to either burn the hay or dissolve strychnine and drench the stacks in order to poison the cattle. Bloom couldn’t quite remember the actual amount he was paid: $50 or maybe it was $150 or $250… it had a fifty in there somewhere. Others claimed Knox had tried to bribe them to change their testimony. Ellis’s witnesses were unsavoury characters, though, and it was highly unlikely they would tell the truth.

Knox was found guilty in spite of a vigorous defence. He was sentenced to three years’ hard labour. Nine months later, Ellis sued Knox, who was still in jail, to recover the value of the hay—$4,000—plus $500 for the weight his cattle lost, plus the $250 reward he had paid to get the evidence against Knox, plus another $500 for loss of time in hiring an extra watchman and a boat to check out another suspect. Knox’s lawyer said his client wasn’t guilty in the first place and certainly not responsible for these costs. The same cast of unreliable characters was called in again to give evidence. The judge declared the previous trial had no bearing on the new trial and unless reliable evidence was introduced to prove that Knox actually burned the hay, he could not be held liable. The jury found in favour of Knox, and Ellis had to pay the trial costs. By this time, Knox had served most of his three-year sentence.

The Vernon News subsequently noted that A.B. Knox, “who had been absent for some time,” was warmly welcomed back by his many friends and had again taken charge of his large ranch. Two years later, Knox donated a lot on the southeast corner of Richter Street to the Presbyterians and added a further $250 toward the construction of their church. Five years later, Knox was elected president of the influential Agricultural & Trades Association of the Okanagan Mission, which had, on its board of directors, a number of the community’s leading citizens. This curious episode in the Okanagan Valley’s history was made even more so when Knox retired and sold his ranch and all his cattle to his adversary, Tom Ellis.

The Ill-fated Postills

After living in Ontario for several years, the Postill family, originally from England, arrived in the Okanagan in 1872. Edward, Mary, their three sons—Alfred, the eldest at twenty, William and Edward Jr.—and daughter, Lucy, had travelled to Yale by steamer and then overland to Kamloops, where Edward became ill. Not wanting to delay their journey, the family placed Edward on a makeshift stretcher, attached to their stagecoach, and continued toward their destination. Edward died near Priest’s Valley (near Vernon), and his body was carried to the family’s new home and buried in the meadow of the ranch he had never seen. He was fifty-two years old.

The Postill family went on to build a “commodious” house with a long, winding lane—visitors could be seen approaching long before they reached the door. The ranch flourished as Alfred took over the business end of farming while William looked after the cattle. The family holdings soon grew to five thousand acres, with an additional two thousand acres of grazing range a few miles away. They had the largest herd of cattle in the Mission Valley and bred some very fine horses. Sheep and pigs were added to the ranch, and the Postills also ran the sawmill that had been left behind by a previous owner.

Always on the lookout for a new opportunity, Alfred was one of the first in the valley to plant an apple orchard and a berry patch. The dry benchlands became productive when the family planted the first alfalfa grown in the area and their prize peanuts took awards at the 1896 Vernon Agricultural Fair. Alfred was a man ahead of his time: in 1891, and at the cost of fifty-five dollars a mile, he had the first telephone in the valley installed between his ranch house and that of his brother, William. The line was then extended to Thomas Wood, Alfred’s neighbour five miles to the north along the wagon road linking Priest’s Valley to Okanagan Mission.

The fruit industry was also taking hold elsewhere in the province and orchards in the Fraser Valley, on Saltspring Island and in Lytton began producing more apples than their local markets could absorb. Seeking to develop marketing opportunities elsewhere, the first meeting of the BC Fruit Marketing Board was held in Vancouver in 1889. Alfred Postill attended as the only Okanagan member of the organization. The board represented a diversity of interests, including those of George Grant MacKay, a well-known and successful land promoter from Vancouver. MacKay was sixty-two years old when he arrive in Vancouver to check out Western Canada and decide if it was a suitable place for his son to settle. He was so impressed with what he found that he sent for his wife, daughter and son to join him. Alfred Postill’s advocacy of his valley’s fruit-growing potential likely caught the attention of MacKay. It was a fortuitous encounter, as G.G. MacKay would soon play a very significant role in the transformation of the Okanagan.

The Postill house was the social centre of the northern part of the Mission Valley and people would rarely travel the wagon road without stopping off for a visit. Alfred became a Justice of the Peace and presided over the court proceedings when Knox and Ellis argued their hay-burning case. Lord and Lady Aberdeen, who arrived in the valley in 1891, were frequent visitors at the Postill home. Unfortunately Alfred, despite his enormous zest for life, followed the path of his father and died in 1897, when he was only forty-five years old. The ranch was sold in 1903 to Price Ellison, the area’s Conservative member of the provincial legislature.

Today the original Postill ranchland wraps around Kelowna International Airport. It has had a succession of owners, including Countess Bubna of Austria, who named it the Eldorado Ranch; Austin C. Taylor, the Vancouver horse-racing magnate and entrepreneur, who doubled the size of the ranch and made some attempt to raise purebred cattle, though he used the land mostly for hunting pheasant; and the Bennett family, who bought the ranch in 1969. It remains a cattle ranch, though some areas of it have been leased out for growing echinacea and ginseng. The graves of Edward, Alfred and William Postill remain within an enclosure on the meadow.

The Italians Followed

The Catholic Church also enticed a number of Italian immigrants to settle in the Mission Valley. A fortuitous encounter between a bewildered Giovanni Casorzo, his friend Paulo Guaschetti and Father Caccola, an Oblate priest, encouraged the two men to join the other settlers at the Mission. Caccola, who had recently returned from Corsica and understood the Italian dialect spoken by the two men, overheard them talking about how much they disliked cutting logs in the nearby forests and wondering what else they could do.

Casorzo had left the political turmoil of Italy in 1883 to make his way in the New World. The thirty-four-year-old father of three landed in New York City but found no contentment in the turmoil of the concrete city: he longed for an opportunity to follow in his father’s footsteps and work the land. Casorzo made his way to San Francisco, caught a ship north to Nanaimo and crossed to the mainland, where he and his newly acquired friend encountered Father Caccola in the mid 1880s.

Father Pandosy soon offered the men a job at the Mission and said that if they would stay for the next six years, the missionaries would help them establish a homestead. Their job would be to do whatever needed to be done: act as cook, ranch hand, cowboy, carpenter, Native agent, teamster or packer. Giovanni Casorzo planned to save his money and send for his wife, Rosa, and his children: Caroline, Tony and the as-yet-unseen Carlo Enrico, soon to be known as Charles.

Giovanni had stayed in touch with his family and sent small amounts of money to them from New York. When he got to the Okanagan he realized the only international currency available to him was gold dust, so he sent small amounts of the precious metal to Italy, though he was never certain it would arrive. Rosa must have received the funds, or perhaps someone in the Oblate order stepped in to help, because passage was booked for Rosa and her children on a windjammer leaving Genoa, Italy, for San Francisco, via Cape Horn, in 1884. Rosa packed food for the journey, and six weeks after leaving her homeland, she and her young children were dropped on the dock in San Francisco. Rosa spoke no English and the only indication that her journey hadn’t ended was a small piece of paper she clutched in her hand. It read “Father Pandosy, Okanagan Mission.” By a stroke of luck—or perhaps divine intervention—someone noticed a large crate that had been left at the shipping office. A label identified the contents as a church bell that was to be sent to Father Pandosy at Okanagan Mission. The bell, a gift for the Oblate’s church, had been ordered by Joseph Christien, one of the valley’s early settlers. It had been cast in France and shipped to Okanagan Mission via San Francisco, and was subsequently named “MaryAnn” in honour of Christien’s wife.

Rosa Casorzo did not let the bell out of her sight as she and her children boarded another boat to New Westminster. Giovanni had asked friends to watch for his family and when the bell was finally loaded onto one of the Fraser River sternwheelers, Rosa and her children followed. It took two weeks for the bell and the Casorzos to get to Yale and then to Kamloops. There, a stagecoach was waiting for the family—and the bell—to take them on the final leg of their amazing journey.

Giovanni was out in the hills when his family arrived but they were welcomed by the priests and taken to their new home. Before long, Rosa became the mission’s cook and her salary of $7.50 a month added to the family’s income. Later that year, Giovanni registered his pre-emption, though there was a shortage of surveyors and the land wasn’t officially surveyed until 1889. The swampy acres on the south side of Mission Creek were thick with underbrush, alders and scrawny birch, and needed to be cleared. Giovanni made a deal with the missionaries to buy two sows on instalment, and then borrowed money from Eli Lequime after Marie Louise convinced her husband the Italian would be a good risk. The land was fenced with the help of their Native neighbours and then drained by lining the ditches with long poles to create channels that would carry the water away from the site.

Rosa Casorzo became an independent, resourceful woman. She worked alongside Giovanni as they both learned to speak French and the Native dialect. They also relied on the knowledge and skills of the Indigenous people and were able to survive poor harvests and medical emergencies by adopting their wilderness cures. These served the family well, as the nine children eventually born to the couple all survived, when many others didn’t. Rosa also became very resourceful and used her needle and thread to stitch up the wounds of her children, as well as those of others who sought her help.

The spelling of the family’s name changed from Casorzo to Casorso when the children started at the Mission school, and when the priests called Giovanni “Jean” (soon anglicized to John) everyone was far too busy with survival to make a fuss, and the changes remained.

One day a stranger arrived at Casorzo’s farm offering to swap a bull and a few heifers for enough vegetables and supplies to get him out of the valley. Giovanni agreed, then discovered the cattle were across the lake and he would have to go and get them. He had two choices: one was a long arduous journey around the south end of the lake and up the west side to find the cattle and a return trip home the same way. The second and much shorter option would be to borrow a canoe to cross the lake and hire the McDougall family’s old scow to carry the cattle back across. Giovanni chose the second option and had his horse swim over behind the canoe. Once he had rounded up the cattle and loaded them all onto the scow, he grabbed the oars and headed out. Just as they were about to land, the wind blew up and the animals panicked. The horse leapt off and headed to the eastern shore; the cattle bolted and swam for the western shore. Giovanni tossed the canoe overboard, jumped in, and abandoned the scow. It took awhile but he eventually rounded up the cattle and his horse and herded them to his side of the lake. The scow soon drifted to shore, so Giovanni rowed it back across the lake with his canoe on board, and returned it to the McDougalls. They were unimpressed with his tale… said it happened all the time.

Giovanni worked for the Mission for many years while his family and his farm grew and diversified. As his children left home, they purchased other properties nearby. The family’s original log house can still be seen south of Father Pandosy’s Mission, across the Casorso Road Bridge. The Casorzos were the first Italians to settle in the area. Others, including the Rampone, Turri, Capozzi and Ghezzi families, followed.

The First Settlement

During the 1880s, there was little change in the lives of the Mission Valley settlers. Their world was defined by their farms, and most didn’t move far beyond the Okanagan, even as the next wave of gold seekers headed east to Grand Forks or farther south to Fairview, near Oliver. While those growing areas could have been markets for the Mission Valley’s produce and cattle, transportation was a formidable challenge and most farmers continued to rely on those living nearby or passing through to sustain them.

By the final decades of the nineteenth century, a small community had begun to develop around Father Pandosy’s Mission. Most settlers avoided the lakeshore, where the land was marshy and often flooded, and instead established their farms inland. Frontier life became less harrowing as the settlers grew what they needed to sustain themselves and sometimes enough to sell to those passing through. A wagon road eased travel to the north and the Dewdney Trail provided access to Hope for mail and supplies. Father Pandosy’s original trail along the east side of the lake remained challenging: it was used when there was little choice, but it didn’t encourage travel southward.

Still, survival itself was often remarkable, and while some thrived, others didn’t make it. Many of those arriving in the Okanagan at this time were adrift in the world without the ties of family, church or community. Even those who found a place for themselves were often faced with near starvation, contaminated water, diseased milk, broken bones, measles or fevers, and were provided with only the most rudimentary of medical care, if any at all. Cheap alcohol was always available; time hung heavily during the long winters and gambling could be a ruinous diversion. Spousal and child abuse were prevalent, and discrimination against the aboriginal population was growing as more settlers arrived in the area. Hardy women made do with little and their children took on responsibilities beyond their years. Survival itself was often remarkable, and while some thrived, many didn’t make it.