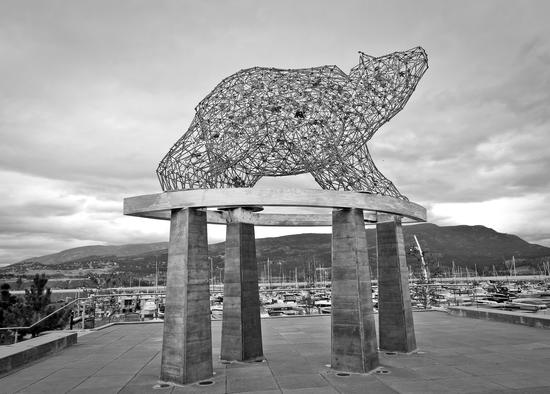

Chapter Seven: The Past Thirty-five Years—Kelowna Finds Its Heart, 1976 to the Present

Kelowna’s iconic Spirit of Sail sculpture was suspended from a helicopter in October 1977, flown down the middle of the lake and gently lowered onto the fountain at the foot of Bernard Avenue. The artist, Robert Dow Reid, had created it in his Okanagan Mission studio, where he’d sculpted since arriving in Kelowna in 1964. Most of his works were much smaller in scale, and Kelowna’s sculpture was the first of his monumental pieces to be installed. It was the second sculpture to be placed in the fountain; the first had been a series of cement half-circles arranged around a central plume that shot a great geyser of water forty feet into the air. It looked wonderful for the six warm months of the year but for the remaining months it simply sat as an inarticulate bunker at the end of the main street. The original designer also apparently didn’t know about the Bear Creek winds that gusted across the lake most summer afternoons. It didn’t take long before pedestrians and building owners complained to city hall about being drenched by the wind-whipped geyser.

The fountain was originally a tribute to Pasquale “Cap” Capozzi, who had arrived in Kelowna in 1920 and established a number of thriving businesses, including City Grocery, the Capri Shopping Centre and Hotel, and Calona Wines. The fountain was initially going to be built in the bay at the foot of Bernard Avenue until sailors and boaters complained it would be a navigation hazard. Then there was talk of putting it at the end of a pier before it was realized there was no money to build a pier. The grass at the foot of Bernard Avenue eventually became the fountain’s default location. When it was decided the geyser had to go, city staff began looking for alternatives; the suggestion of a bronze likeness of Premier W.A.C. Bennett in the middle of the fountain didn’t gain much support.

It was finally an off-chance visit by a member of city staff to the Dow Reid Studio that revealed a three-foot-high version of the sails sculpture. City council was interested and when the small sculpture was displayed at the Capri Mall and comments were positive, the decision was made. The concrete half-circles and the geyser were removed and replaced with the creative and somewhat abstract Spirit of Sail.

The arrival of the sculpture in downtown Kelowna seemed to change the community’s focus. While city hall dealt with the implications and fallout from the recent boundary expansion, things began to happen downtown. When CN decided to sell its marshalling yards and wharfs in the north end in 1975, Kelowna had the wisdom to buy them. In anticipation of future development, sewer pipes were installed but those in charge were apparently unaware that most of the land had previously been swamp and bog. It wasn’t long before the pipes had disappeared into the water-soaked soil among the sawdust and slabs that had been used to fill the swamps. The experience gave rise to the notion that Kelowna’s downtown couldn’t support high-rise development. The problem was overcome when new engineering methods were introduced, which usually involved preloading the proposed development site with mounds of soil for several months to force the residual water from the ground prior to construction.

It took several more years for the city to figure out what it wanted to do with the site. Left empty, the land was muddy and covered with weeds until a proposal call was sent out in 1988 soliciting plans to develop the property. The city talked about parkland, condos, a destination hotel and a convention centre. The submissions were fascinating, exotic, totally impractical, engaging and sometimes oblivious to the city’s requirements. Though the decision to go ahead with a mid-market Calgary-based hotel developer was risky, the lagoon system and lakefront park that were part of the proposal had enormous appeal.

A large section of the old railway marshalling yards and wharf was transformed into Waterfront Park. Brandt’s Creek had run through the area for years but had been neglected—and was an outlet for industrial waste. At one time, an unintended discharge from Calona Wines left the neighbourhood ducks staggering in delight as they clamboured in and out of their wine-laced pond. The creek bed was also full of debris and overgrown with weeds. The area was restored as part of the project and is now known as Brandt’s Creek and the Rotary Marsh. Osprey, mallards and tree-eating beavers have made the wetlands their home. The new park also included a swimming beach, created at Tugboat Bay, and the Island Stage, built in the lagoon. Simpson Walk, named for S.M. Simpson, circles the reclaimed land around the lagoon. Waterfront Park opened in 1995 as part of the transformation of the derelict railway yards; it also includes the Grand Okanagan Lakefront Resort and the Dolphins and Lagoon condo developments. The area has become one of the city’s signature residential and hotel areas as other condos have been added, overlooking what is one of the community’s best utilized and most beautiful parks.

The crumbling Laurel Packinghouse was set to be bulldozed out of existence in the early 1980s. Built of bricks made from Knox Mountain clay in 1917, the Laurel was the oldest, largest and last of BC’s historic packinghouses and its demise would have obliterated the remaining vestiges of Kelowna’s once vibrant fruit-packing industry. The city was reluctant to save the building, but after much persuasive lobbying it relented, restoring the packinghouse and recognizing it as the city’s first heritage building. When it opened in 1988, the main floor was used for displays and various public functions while the second floor office space was made available to various arts and commercial groups. To commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the founding of the British Columbia Fruit Growers’ Association, the Orchard Industry Museum opened in the Laurel in 1989. The BC Wine Museum and a VQA wine shop opened in the building ten years later.

The Kelowna Art Gallery was created in 1977 and for a number of years shared display space in the Kelowna Museum. Plans were underway to build a stand-alone building on the parking lot in front of the museum until the board was encouraged to look farther afield. Amid some consternation, they chose instead to build their new gallery on the old industrial land across from the new hotel complex. The facility is home to a number of different galleries, all of which meet national standards for the storage and exhibition of artworks. Most of the gallery’s collection has been created since 1940 and focusses on historical and contemporary visual arts, and particularly landscape images of the Okanagan.

The architectural gem of the area is the Kelowna branch of the Okanagan Regional Library. The building’s design evolved when many stakeholders participated in a fractious day-long workshop. The various community members somehow managed to resolve all their issues and moved ahead, then celebrated the opening of the new library in 1996. It was also built on what had previously been Kelowna Saw Mill property. The surrounding green space adds air and light to the increasingly dense neighbourhood though the open spaces may be slated for future development as the city attempts to recoup some of the costs of acquiring the land.

The latest addition to what has become known as Kelowna’s cultural corridor is the Rotary Centre for the Arts. The new building was built over and around the old concrete-block Growers Supply building and came about after years of complaining, lobbying and fundraising by the local arts community, who were perpetually short of affordable performance, studio and storage space. The building, which opened in 2002, houses the 326-seat Mary Irwin Theatre, artists’ studios, an art gallery, a dance studio, a bistro and rental space. Affordability continues to be a challenge for the arts groups who lobbied and worked so hard to create the building.

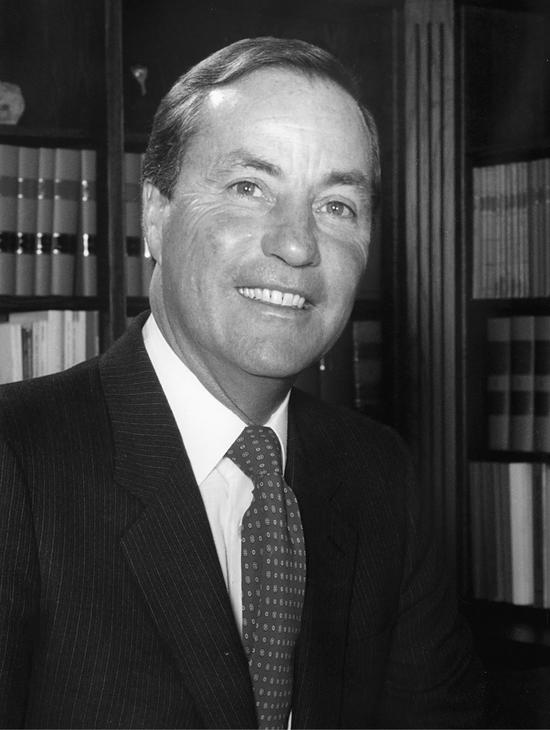

Bill Bennett

Following in the footsteps of a popular, larger-than-life leader is challenging at best, but when that leader was your father, it’s huge. From the start of his political involvement, Bill Bennett knew he wasn’t the populist his father had been. Neither was he a showman, and initially he had the speaking ability of a wooden statue, though he improved with time. Bill also knew a high-visibility leader was a magnet for the media and decided he didn’t need to be centre stage all the time. By the end of W.A.C.’s time in office, the Social Credit Party was in disarray. Members had drifted off, the organization had all but vanished and election readiness wasn’t an issue—whenever Premier W.A.C. had called an election, he was ready and the party only needed to be marginally involved. When Bill declared he would seek the leadership, his first step had to be the revitalization of his own party. Most thought Social Credit was dead and began looking around for another party that could bring the Liberals and Conservatives back to life.

Bill had done his homework. “Build with Bill” became his slogan and when he ran for the leadership he was ready and handily defeated his opponents. Then he travelled the province rebuilding his party, enticing members of the other parties to get on board. Tina the elephant joined the last campaign rally before the 1975 election… apparently trumpeting the change in government that Bill and the Social Credit Party were sure was going to happen. Dave Barrett and the NDP had been in office for 1,200 days and his rationale for calling an election has never quite been understood; perhaps it was because his predecessor had called elections every three years. The NDP had been unprepared to govern: money was spent with little accountability, governance was sloppy and back-to-work legislation had alienated the Party’s labour constituency. In contrast, the programs the NDP brought in, notably the ALR and the Insurance Corporation of BC (ICBC), were innovative and left intact when the party was defeated. However, the NDP had also amalgamated Kelowna with its neighbouring communities and brought in similar legislation for Kamloops and Prince George. Most voters in these communities weren’t impressed.

Bennett campaigned on the NDP’s lack of fiscal accountability and sloppy management, and won the election. The time between father and son Social Credit premiers was only three years. Bill lived in the Harbour Towers Hotel during the time he was in Victoria, took over Dave Barrett’s old car and headed back to Kelowna every weekend he could. Not being drawn to the cocktail circuit, he worked long hours and expected everyone else to do the same. Bill deferred to his cabinet ministers to introduce legislation, and also justify it and the costs involved. Most found the opportunity unique and fulfilling, though they knew Bill was keenly aware of whatever was going on.

There were a number of challenges during his three terms in office: the NDP had taken over several companies, which didn’t sit well with the free enterprise mantra of the Socreds. BC Resources Investment Corporation, soon referred to as BCRIC, was created and everyone in the province could apply for five free shares of the company. Almost ninety percent of citizens took up the offer and the novel concept made for huge headlines in the newspapers, but when various scandals also hit the headlines BCRIC shares ended up as wallpaper. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, the worst recession ever hit the province, skyrocketing interest rates and collapsing resource revenues. Wage restraints were introduced after teachers won a twenty-one-percent wage hike. The government introduced the most drastic restraint program the province had ever seen.

Bill had already decided that this would be his last term in office and as protest marches blanketed the province, and his family received death threats, Bill made concessions, but on his own terms. Bennett wasn’t the province’s most popular politician though most people grudgingly respected his decisions. There were some major accomplishments during his term of office including Expo 86, the domed BC Place Stadium and Vancouver’s Trade and Convention Centre. To balance out the perks to Vancouver, the Coquihalla Highway would tie the Lower Mainland to the Southern Interior, and the port at Prince Rupert and Tumbler Ridge coal would provide economic stimulus in the north.

Bill was a pragmatist who saw the big picture and looked for the best solutions with that in mind. He rewrote the province’s financial accountability legislation, was a principled leader who did what he thought was best and saw the province through one of the most challenging times in its history. In contrast to W.A.C., the charismatic leader who built during the good times, Bill was seen as an aloof no-nonsense leader, one who also left a positive legacy to the province but did so during the toughest of times. He led the government through three elections over eleven years, and left office in the middle of Expo 86, having completed the list of things he wanted to accomplish before stepping down.

BC politics are often described as wacky, zany, weird and wonderful. The province hasn’t always followed the more traditional political model and party leaders have often added their own colourful and unconventional take on their role, including Premiers W.A.C. Bennett and Bill (W.R.) Bennett. A Bennett from Kelowna had led the Social Credit Party as the premier for thirty-one of the previous thirty-four years. It was quite an amazing family commitment to public life, and an unquestioned commitment to the development and betterment of BC.

Unprecedented Growth

As the province worked its way out of the economic crisis of the 1980s, Kelowna began to thrive. Retirees arrived to settle, families from Alberta built holiday homes, and space that had previously been designated for agricultural use became available for residential development. A projected fifteen-year time period to build the area suddenly collapsed into a four- to five-year completion schedule. In the ten years between 1986 and 1996, Kelowna’s population grew by over 28,000 people. The impact on schools, hospitals and recreation facilities was profound.

Kelowna General Hospital got its first emergency department, more long-term beds were added to Cottonwoods Extended Care facility and plans were made to add another acute care and diagnostic centre to the hospital. In 1985 the province announced that a new cancer treatment centre would be built somewhere in the province. Kelowna, Prince George and Kamloops each began intense lobbying campaigns to have the facility built in their community. In 1989, amid a fair amount of animosity, Kelowna was chosen as the location. Ten years later, the BC Cancer Agency Centre for the Southern Interior opened. The Southern Interior Rotary Lodge opened a thirty-five-bed facility the same year to provide support and accommodation for patients undergoing or being assessed for cancer treatment.

As the population moved outward from the original town centre, so too did many of the services: schools at all levels have abandoned their downtown locations and been replaced by modern or renovated buildings in the suburbs. The Parkinson Recreation Centre continues to provide pool and recreation services. On the outskirts of town when it was built, it now sits in the community’s geographic centre. Rutland has had the benefit of Athans Pool since the 1980s, and with recent renovation and expansion it continues to offer a broad range of programs to its members. With Okanagan Mission’s population growth and the city’s need for more ice rinks and playing fields, a new recreation complex opened on what was a portion of the Thomson family’s farm. It took more than one try and a few years before the city was able to convince the Agricultural Land Commission to release the often boggy, waterlogged land for its use. The Capital News Centre opened in 2004 offering indoor soccer and baseball fields, ice rinks and fitness space. The H2O Fitness Centre opened five years later in what had once been an adjacent field, offering state of the art swimming and wave pools.

2,4-D Is Not For Me

By the mid-1970s, environmental issues began creeping onto the public agenda as Okanagan newspapers talked of threats from an “alien invader.” Eurasian milfoil is a nuisance aquatic plant that spreads quickly, crowds out native species and creates a dense mat of weeds, which is a menace for boaters and unpleasant for swimmers. New plants grow from stems broken off the main plant, which float and re-establish themselves quickly nearby. The initial fear was that the weed would keep reproducing and invade greater and greater areas of the lake, making it unusable. As milfoil spread throughout the Okanagan lake system, outraged citizens mobilized against the province’s attempts to eradicate the weed by applying the “moderately toxic” herbicides diquat and 2,4-D. Washington state was using the chemical and the BC government declared complaints by local environmental groups were irrational, unscientific, and their mantra of “2,4-D is not for me” unhelpful.

Kelowna’s medical health officer, Dr. David Clarke, was alarmed, and when the mayor of the day declared the city would only harvest the weeds mechanically and not use the herbicides, the province refused to pay. They insisted that both methods had to be used to tackle the weeds, that pesticide drift would be minimal and swimmers would not be affected, and that they would avoid all water intakes. When the province declared Vaseux Lake, at the south end of the valley, off-limits for the herbicide application because it wanted to protect migratory birds, the lapse in logic didn’t seem to register.

The South Okanagan Environmental Coalition in Penticton commissioned reports, applied for injunctions and threatened to jump into the weed beds where the pesticides were applied. The RCMP was called in and those running in municipal elections sidestepped making decisions by lobbying for a referendum. The herbicides were applied to about thirty-five acres of test plots in various Okanagan lakes. Injunctions to stop protesters were appealed in the Supreme Court; ministry officials declared the weeds were dying and the test was a success. Environmental groups looked at the same test patches and saw no change. By early 1979, the public outcry had become so loud that the province declared 2,4-D to be too dangerous to use and announced that mechanical harvesting would replace the herbicides.

There was a gradual shift away from eradicating the weed to controlling the spread, though some efforts to get rid of it persisted: jets of water were used to dig plants up by the roots but this also reconfigured the lake bottom and was stopped. Then the tops of the weeds were cut off and piled on the beaches until sunbathers fiercely complained about the ghastly smell. At other times the valley’s scuba divers were hired to vacuum the lake bottom and suck up the milfoil roots. When the vacuum inhaled an unexploded mortar shell near Vernon and bomb demolition experts had to be hastily dispatched from Ottawa, the project ended.

As mechanical harvesting became the most viable option, a number of creative inventors devised machines to do the job: the “Aquanautus Billygoatus” won the $10,000 design prize, but the machine was never built. The Okanagan Basin Water Board took over weed management in 1981 with a combined program of rototilling the weed beds during the winter and harvesting them in the summer. They built their own machinery, ingeniously adapted it when necessary, and then retrieved the machines when they sank. The board continues to manage Eurasian milfoil within the Okanagan Lake systems and has been successful enough that the weeds rarely show up on the public’s radar today. Though most of the story of the environmentalist community’s adamant stand against 2,4-D use in the valley’s lakes has been lost to time, resident action was enormously significant in preserving the somewhat tenuous quality of the Okanagan’s water supply.

Exploding Development

When the northern part of Glenmore Valley was absorbed into greater Kelowna in the 1973 boundary expansion, it was recognized that the bottom lands were plagued with frost pockets and clay soil, which challenged even the most stalwart orchardists. Kelowna applied to the Agricultural Land Commission for the release of Glenmore’s valley floor from the new Agricultural Land Reserve in 1977. This was the first large-scale application received by the commission, and by the time decisions were made BC had slid into economic turmoil. All the development in the area stopped and the growth that drove it ground to a halt. Between 1981 and 1986, Kelowna’s population only grew by two thousand people and there was almost no demand for new housing.

By the end of the 1980s, the world had begun to change and developers suddenly converged on Glenmore landowners, wanting to buy their property. Large homes on small lots began to proliferate as walled retirement communities appeared amid discussions about whether this new kind of housing was a benefit to the community or not. The city carved out large slices of land for future roads, and the landscape was soon devoid of trees as the Glenmore Valley was transformed from its rural roots into an urban community in an astoundingly short time. The area grew by seven and eight percent per year. Kelowna’s population, between 1991 and 1996, grew from 75,950 to 89,442. The majority of that development was in the Glenmore Valley. The clay soil created challenges for builders, more domestic water users tapped into the Irrigation District system and the social fabric of the community was challenged by the rapidity of the change.

It’s a High Price to Pay

The turmoil that followed the creation of the Agriculture Land Reserve continued as the original plan to pay farmers for the development potential of their land was scrapped. A farm income stabilization program was created in its place and continued until 1991. At that time, there were about 26,000 acres of orchards in the valley, most of which were apples. As government support declined, growers found it increasingly difficult to maintain their orchards and respond to changing market preferences. The amount of fruit being produced also declined, as did the infrastructure supporting the orchardists. Between 1957 and 1972, the number of co-op societies and packinghouses had shrunk from thirty-six to fourteen. The number of independent shippers fell from twenty to four during the same period. In 1998, those fourteen packinghouses became four. In 2008, the four remaining co-ops—in Osoyoos, Oliver, Kelowna and Winfield—folded into one operating company, the Okanagan Tree Fruit Co-operative. It owns four packinghouses with BC Tree Fruits Ltd. as its marketing company. Three independents also remain in operation.

All Those Apples

Events beyond the Okanagan have had a profound impact on the valley’s orchards. Washington had no apple industry during the 1930s and 1940s, but when W.A.C. Bennett opened the province for business and built hydroelectric dams on the Columbia River as part of that plan, he signed on to cross-border water sharing agreements. Before long the Columbia River Irrigation Project was irrigating the Wenatchee Valley, and Washington’s Red Delicious apples began taking over traditional Okanagan markets, often selling at a lower price. Then Wenatchee began calling itself the “Apple Capital of the World.” For awhile, government support for orchard replanting programs in BC helped growers to change to more marketable varieties and meet the competition. Those programs, for the most part, have vanished.

An Okanagan with No Apples?

Though apples are Canada’s most popular fruit and the Okanagan’s biggest cash crop, the industry is struggling to survive. Many orchardists wonder about the future as they deal with competition from low-cost imports, changing consumer preferences, bad weather, low prices, labour problems and increasing overhead. It’s impossible for people to imagine the Okanagan without its orchards, though many orchardists are concerned about their survival. In better times, packinghouses were located at railroad sidings, dotted among the orchards and scattered up and down the Okanagan. Now there are only about eight hundred orchardists in the valley and, since the 2008 amalgamation, the single Okanagan Tree Fruit Co-op. This one organization receives, stores, grades and packs apples, pears, cherries, peaches, nectarines, apricots, crabapples, prunes, plums and table grapes. It also stores and warehouses the fruit and uses BC Tree Fruits Ltd. for sales and marketing.

The early favourites—the McIntosh, Yellow and Red Delicious, and Spartans—have lost some of their popularity and been replaced by the Galas. Growers of the Royal Gala and the Aurora Golden Gala now risk producing into an oversupplied market, and the Golden Gala is no longer commercially viable because its unpredictable markings have reduced its market appeal. The Ambrosia is the newest and most popular variety to be introduced. The variety seeded itself in Similkameen Valley in a new planting and when pickers kept devouring the apples from that particular tree, the orchardist knew he had something special. It’s taken a few years for production to reach commercial levels but this new crisp arrival is now in demand.

The number of orchard acres is shrinking and production along with it. The drop from the maximum of 10 million boxes of apples produced in the late 1980s to 3 million boxes today is significant. With only about eight thousand acres now planted in apples and grapes at about nine thousand acres, the Okanagan Valley’s agricultural landscape is in the midst of significant change. The injustice of the system rankles the orchardists: the cost of land is so high that new orchards are unlikely. Various levels of government promise to support programs like the Sterile Insect Release (SIR) program, which reduces the need for pesticides, and then renege on their commitment and the cost falls to orchardists. As houses cover the hillsides, wildlife are driven down onto the valley floor and into the orchards: deer are notorious for taking one bite out of a peach, a pear or an apple and then moving on to the next. Orchards that previously didn’t need fencing must now be enclosed to save the crop.

Today, the Wenatchee area has over 170,000 acres of orchards and is likely the apple capital of the world. The Okanagan, its nearest competitor, is fast becoming the smallest producer in Canada. Washington dumps its apples into BC and the industry is too small to be able to fight back. Grocery chains undermine local growers for a cent or two a pound and consumers don’t seem to notice—or care. The replant programs, which were a major factor in establishing the grape industry, have not been available to apple growers for some time. Orchardists who can no longer survive financially are pulling out their trees and returning their land to hay and pasture… and turning the clock back a century, to before the rangeland was divided into small acreages so it could be planted in orchards.

Kelowna and the northern part of the valley are prime apple-growing areas. Orchardists feel they are losing both government and community support to maintain what most residents see as an integral part of their community. Will we notice when we no long see or smell the apple blossoms? What will replace the apples if they are no longer a visible marker of the history and abundance of the Okanagan? It’s a question worth pondering.

The apple by-products business is also changing. Sun-Rype Products Ltd. continues to buy industry culls though at today’s price of between twenty and twenty-eight dollars a bin, it’s a very thin return for the growers. The company is also diversifying its product line and has recently purchased Yakama Juice in Washington state. The company, previously owned by the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, has been a key supplier of Sun-Rype products for several years. The purchase also gives Sun-Rype processing and manufacturing facilities and expanded marketing opportunities in the US.

Wine Takes Over

The Okanagan’s wine industry went through a remarkable transformation during these years. Vineyards of hybrid grapes had been part of the Kelowna landscape since the 1930s when most were shipped to the fresh fruit markets on the Prairies. Yet it wasn’t a profitable venture and many growers grew tomatoes between the rows to sustain themselves. These grapes were also used to make the early Okay sparkling white wine and Calona’s Royal Red when efforts to make apple wine weren’t successful. Some Okanagan grapes were also sent to the Growers Winery in Victoria to replace the loganberries they had started out with. When apple prices dipped, many orchardists dug up their trees and planted grapes.

The Rittich brothers arrived in the Okanagan from Hungary in the 1930s with years of experience working in various European vineyards and wineries. They experimented with forty varieties of vinifera (the classic European wine grape) vines, chose the most promising, pruned them low to the ground and buried them to ensure they survived the cold valley winters. The practice was popular in some parts of Europe but it didn’t offer much of an incentive for the valley’s growers to replace their old hybrid vines. Though not one of their original favourites, the Rittichs’ Okanagan Riesling grape was successful and continues to be grown in many parts of the valley today.

BC’s wine industry began to thrive when “pop” wine appeared in the early 1960s: Baby Duck, Love-A-Duck and Fuddle Duck, among others. They were wild concoctions of fermented grapes, sugar and water, and resembled soft drinks. A group of local businessmen were convinced they could capitalize on the country’s new enthusiasm for wine and founded Mission Hill Winery in 1967, across the lake from Kelowna. The winery was sold three years later to the colourful Ben Ginter, a road builder and brewer from Prince George. He changed the winery’s name to Uncle Ben’s Gourmet Wines. Other wineries struggled to keep up with exploding demand for pop-style wines and encouraged growers to plant more hardy hybrids: quantity mattered more than quality. When winemakers couldn’t get enough local grapes, they imported California grapes and unfinished wines to cover the shortfall.

By the end of the 1970s, tastes became somewhat more sophisticated and wine lovers began searching for alternatives to Baby Duck and his friends. Some of the imported products became popular and benefitted from marketing campaigns designed to tap into the appeal of the newly popular European wines: a Marlene Dietrich sound-alike sang the merits of Hochtaler’s light white wine while Calona’s Schloss Laderheim, with European castles on its label, became Canada’s bestselling white wine. Both remain on the market today.

The valley’s wineries held promise and the grape industry was stable, though its future looked modest at best. Then Dr. Becker, a German wine expert, was invited by his former student, Walter Gehringer, an assistant winemaker at Andrés Wine, to tour the valley and recommend ways to improve the industry. The study took almost ten years to complete but he identified some vinifera grape varieties that could thrive in the valley’s climate. Many of these varieties have gone on to become the base for the Okanagan’s now-thriving wine industry. The grape industry began to move beyond quantity and focus on quality: it was a seismic transition for one of the valley’s oldest businesses.

However, it was NAFTA—the North American Free Trade Agreement—in 1989 that propelled the industry into what it has become. BC wines at the time were marked up by fifty percent in the liquor stores while imported wines were marked up one-hundred-and-ten to one-hundred-and-twenty percent. The new trade agreement levelled the marketplace and BC wineries lost their competitive advantage. The industry was plunged into more uncertainty than it had ever experienced. Then the federal government provided a one-time grant to help the wineries adjust to the NAFTA requirements. BC’s grape growers chose to use the grant of eight thousand dollars per acre to pull out their hybrid vines and the additional thousand dollars to replant viniferas. When the program was announced, over 3,000 Okanagan acres were planted in hybrids. When it ended, less than 350 remained. Today, over 9,000 acres of vinifera vines are planted throughout the valley.

In 1985, there were ten wineries in the valley, two of which were in Kelowna: Calona, dating back to the 1930s, and Uniacke Estate, part apple orchard and part vineyard. Uniacke was a local curiosity: its slightly Mediterranean building was perched on a remote hillside at the edge of the wilderness, south of town. The only access was along a gravel road. It was one of BC’s first estate wineries, founded by David Mitchell in 1980 and named after his Nova Scotia ancestors. The winery struggled to survive and its future was uncertain until Ross Fitzpatrick, whose family had historic agricultural roots in the south end of the valley, purchased it in 1986.

Ross was initially involved with the tree fruit industry when, after being awarded a UBC degree in commerce and business administration, he became research director to the Royal Commission into the Tree-fruit Industry of British Columbia in 1958. When his work with the Royal Commission was finished, Ross worked for BC Tree Fruits before moving on to create and operate a number of businesses in the aerospace, oil and gas, and mining industries in various parts of the world.

Having a strong focus on environmental protection, Ross returned to the Okanagan and to his agricultural roots. With a commitment to promote value-added agriculture, Ross founded CedarCreek Estate Winery, and was among the first growers in the valley to plant vinifera grapes with the goal of producing premium quality wines. Ross Fitzpatrick was subsequently appointed to the Senate of Canada, and from 1998 to 2008 he represented both Canada and the Okanagan-Similkameen in a number of high-profile initiatives.

The development of CedarCreek mirrors the dramatic changes in what has become one of the Okanagan’s leading industries. There are about two hundred wineries in the Okanagan Valley and neighbouring Similkameen Valley. Several have been named “Best in Canada.” The area has become a destination for wine connoisseurs from around the world and has provided other entrepreneurs with opportunities to start complementary businesses. The Vintners Quality Alliance (VQA) program regulates and sets high standards for the area’s wines. An abundance of creative, quirky and unique labels and colourful destination wineries are now nestled among the valley’s lakes and mountains. In the past ten years alone, wine sales have gone from just under $7 million to over $160 million and the average price per bottle has gone from under seven dollars to about twenty. Vineyards have altered the valley’s landscape, and the wineries have changed the area’s tourist focus and conferred a certain cachet and ambiance to the Okanagan that didn’t exist before. The journey from table grapes to vineyards, wineries and “best in class” wines is a remarkable Okanagan success story.

During this same period, much of the southern Okanagan converted to grape production. With the VQA guaranteeing one hundred percent BC-grown grapes—and the market cachet that goes with that—the industry has developed a loyal following. The rapid expansion is now raising questions, however: is the market over-supplied, and might consumers be driven to less expensive imports and away from the costlier local wines in a recession-plagued marketplace?

Tourism

Kelowna bills itself as an international, year-round tourist destination, and relies heavily on the industry for employment opportunities and its economic well-being. The projected 1.2 million annual visitors are tied to 6,900 direct jobs and $130 million in revenue: tourism is one of the largest economic generators in the city. Outdoor activities are the main draw and take advantage of the surrounding mountains, lakes, beaches, forests, orchards and vineyards. Two thirds of the revenue flows into the area in July and August, as water sports and boating remain the biggest draw. However, subtle changes are taking place—the area’s rich cultural heritage is now being showcased by world-class wineries, restaurants, museums and galleries.

The Apple Triathlon, the Centre of Gravity beach festival and the Dragon Boat Festival currently fill the calendar during the warmer months while biking, hiking and wine festivals fill the valley’s shoulder seasons. The city draws meetings, conventions and sporting events such as the BC Summer Games and International World Children’s Winter Games, which attracts people of all ages. For many, the area’s fifteen golf courses, open for play seven or eight months a year, are the biggest draw. Some courses wind around old orchards while others are nestled among the pines and rocks.

Big White and neighbouring Silver Star Mountain are both about an hour away and attract skiers from around the world. Several cross-country ski and snowmobile trails are nearby and a downtown outdoor skating rink is available to all. Kelowna is billed as a city with a progressive modern lifestyle and a wide variety of amenities for tourists. That is also why so many people have moved to Kelowna, or have chosen to have a holiday home in the area.

In a fiercely competitive marketplace, Kelowna works hard to both retain visitors and attract new ones from among those looking for a new and unique travel experience. However, tourism and resource-based businesses are no longer Kelowna’s only major industries. Though still in its infancy, Kelowna’s thriving technology sector has made an impact in the broader marketplace. A well-educated, well-paid workforce has begun to move to town as some of the more traditional industries have moved on: Western Star Trucks departed in 2002 and the call centres that took over some of their space departed a few years later. Various high-tech companies have their headquarters in the Landmark Technology Centre, and the Okanagan Science and Technology Council was formed as a resource and lobbying group.

Okanagan University College

Okanagan College gradually took on an air of permanence in 1978 when construction began on the new campus at the technical school’s KLO Road site. Business and fine arts courses were added to the curriculum, though they had to be taught off-campus for two years until new buildings were ready. That fall, 2,230 full- and part-time students enrolled in vocational, career and university-transfer classes at the one site for the first time. Then came the recession and cutbacks, and the Vernon, Penticton and Salmon Arm campuses feared for their existence—delegations were sent to board meetings to argue against possible closures. Labour turmoil and protest rallies blanketed the province and swept the college up in the furor. The board locked the faculty out over a pay dispute and students occupied Premier Bennett’s constituency office in protest.

Once the turmoil passed, it wasn’t long before both faculty and students wanted more than just the two-year academic program offered. Access to higher education, closer to home and at a reasonable cost, was becoming a priority for everyone in spite of the government’s 1987 declaration that a university in the Interior wasn’t part of its plans. The bumper sticker “Getting there by Degrees” began showing up in the community; the Kelowna Chamber of Commerce created the “Friends of Okanagan College” organization and circulated petitions, sold T-shirts, raised money and lobbied the government. Statistics were on their side: only six percent of Okanagan students received a post-secondary education, versus eighteen percent in the Lower Mainland. An interim solution appeared in 1989 when the college began offering third- and fourth-year courses leading to a University of British Columbia Bachelor of Arts or Bachelor of Science degree, as well as a University of Victoria Bachelor of Science degree in nursing and a Bachelor of Education degree. It was a complicated way to achieve the desired end but applications for admission skyrocketed.

The existing facilities weren’t adequate and space on the KLO site was limited, but plans went ahead to extend labs and build more classrooms. When the college president was driving a deputy minister to the airport and happened to mention his concerns about the college’s confined space, the search for a new site was soon underway. A minimum of 300 acres was needed, hopefully nearby, and on land not within the ALR. The first choice was in Okanagan Mission but it was in the ALR and the application to remove the designation was refused. The search continued until a property near the airport was chosen to become the college’s North Kelowna campus. It was farther from town than was hoped for, but highway access was good. The original KLO site was also “out of town” when the technical school began but development soon followed, and filled the spaces in between.

It was two years before buildings appeared on the north campus. The government was still operating on the college model and scrutinized every minute decision. Others were thinking of it as a university. College faculty offices were to be 80 square feet while university faculty offices were entitled to one hundred square feet. How many square feet should be planned per student? How many volumes should be planned for the library? And the list went on and on. The arts building, science building, library and student services building, along with two residences, were opened in January 1993. The official opening five months later drew nine thousand people—it was a great community celebration.

In 1995, Okanagan College officially became Okanagan University College (OUC) and the change in legislation finally enabled it to confer its own bachelor degrees in a number of fields as well as honorary doctorates in law, letters and technology. Degrees were offered at OUC’s Kelowna campus while Salmon Arm, Vernon, and Penticton became more secure with new campuses as well, offering two-year academic courses and developing their own unique identities. Achieving academic autonomy had been a convoluted and contentious process, complicated by historic valley animosities, but the multi-campus college had finally become a reality.

From OUC to UBCO

The creation of OUC didn’t end the debate about its being a college or a university. Some felt the dream of a full-status university was fading and their institution was becoming a “glorified community college.” Vocal advocates lined up on both sides of the issue. A tuition freeze imposed in 1996 by the NDP government had limited funding, enrolments were declining and course offerings were limited. These were challenging times but no one was ready to eliminate the college’s technology, trades, vocational and adult education programs. The problem became one of maintaining these programs while trying to create a university. A Liberal government ousted the NDP in 2001, fired the college board and improved funding to build a gymnasium at the north campus. It was, more or less, the gymnasium that had originally been promised by Premier W.A.C. Bennett when he opened Kelowna’s BCIT campus in 1961. The fine arts, health and social work programs moved to the north campus and improvements were made to the KLO campus.

The solution came when an announcement was made in Victoria in March 2004 that OUC would be divided: the north campus would become the new University of British Columbia Okanagan (UBCO) and the Vernon, Salmon Arm, Penticton and Kelowna campuses would become Okanagan College… again.

Though some where initially skeptical, the two institutions have established their own identities and flourished. UBCO has added economic, social and academic value to both Kelowna and the region. The campus almost tripled in size in its first five years, enrolments grew from 3,500 to over 7,000, and research funding increased as UBCO focussed on issues relevant to the Okanagan: water, biodiversity, urban sprawl, Indigenous rights and traditional knowledge. Value-added agriculture and organic farming was also on its agenda. UBCO was identified as the site of BC’s fourth medical school a year later. A new clinical teaching building opened at Kelowna General Hospital in January 2010 in conjunction with a new health sciences building at the UBCO campus.

In June 2010, UBCO added 104 hectares (256 acres) of adjacent farmland to its campus. The land doubled the size of UBCO and was added to UBC’s endowment lands, which the institution holds in perpetuity. The land is in the ALR and includes Robert Lake, an environmentally sensitive wildlife refuge. Though a land use plan has yet to be worked out, the new acquisition is expected to enhance the university’s research and teaching opportunities and serve as a living laboratory for future students.

In spite of some misgivings about the future of a reconfigured Okanagan College, shedding the north campus and refocussing its mandate has paid enormous dividends. The four main campuses have expanded both their physical plants and the number of programs offered. Full-time equivalent enrolment exceeds 8,500, while over 12,000 students are enrolled in continuing education courses. Learning centres offer courses in Revelstoke, Princeton, Keremeos, Oliver and Osoyoos. Trades courses that were originally only offered in Kelowna are now offered throughout the Okanagan Valley. Two-year academic programs continue to be offered and allow students to transfer to the university. Clarity of purpose and drive has clearly paid dividends.

Arriving and Departing

In the 1970s, driving to Kelowna from anywhere still took a long time. The Hope–Princeton Highway remained the main route from Vancouver as it was quicker and easier to drive than the Trans-Canada route through the Fraser Canyon. However, it still didn’t bring travellers directly to Kelowna. To the east, the Trans-Canada Highway opened over the Rogers Pass in 1962, which officially completed the highway (though Newfoundland Premier Joey Smallwood refused to attend in the ceremony, calling the “completion” a sham as the route had not been extended to his province). But as important as the route was to Canada, the closest travellers got to the Okanagan was Sicamous, which was even farther from Kelowna than the end of the Hope–Princeton Highway.

By the late 1970s, the BC government decided it was time to improve access to the Interior and began planning the Coquihalla Highway. It would be a toll highway through the mountains and sections of the new route would be built near the original Kettle Valley Railway line: the Shakespearean place names Romeo, Juliet, Lear, Iago, Shylock, Jessica and Portia along the highway still locate the train stations chosen by Andrew McCulloch, the engineer who built the remarkable railway. The new highway would be built in three phases: the first connected Hope and Merritt, while the second connected Merritt and Kamloops; passenger cars would pay a toll of eight dollars. Most importantly, the highway had to be open in time for travellers to visit Vancouver’s Expo 86.

Though the fair opened amid considerable skepticism, it signalled the end of the gloom and confrontational mindset that had engulfed the province during the recent recession. As 22 million people from across the province and around the world flocked to Vancouver for the five-month party, it was hard not to get caught up in the enthusiasm and excitement. Newspaper headlines were full of accusations about over-budget construction costs because of the rush to complete the highway before Expo opened. A much publicized inquiry followed, though it made little difference.

The new highway cut an hour off the drive between Hope and Kamloops and provided another route into the BC Interior. It was still a long way from Kelowna and it wasn’t until phase three, the Coquihalla Connector, was built that Kelowna finally felt some benefit. On October 1, 1990, large crowds gathered at the lookout near the end of the highway where Okanagan Lake first came into view. Bumper stickers encouraged motorists to “Discover the Missing Link” as Mayor George Waldo of Peachland, the closest community to the highway, told visitors to keep their sticky fingers off his pristine valley. Either they didn’t hear him or ignored his cautionary words as the highway not only shortened the travel time between Kelowna and Vancouver, but turned visitors into residents and added to Kelowna’s 1990s economic and construction boom.

A Second Bridge

The first Okanagan Lake Bridge was meant to solve the problem of crossing the lake for all time. By the turn of the century, it was already over capacity. With added traffic and growth, the old floating bridge was a bottleneck—its original two lanes had become three and there was talk of reconfiguring it to four. Perhaps it was cheaper to build a new bridge, one that was elevated over City Park and downtown to avoid the traffic lights? Then a four-lane tunnel was suggested. Though it was an interesting made-in-Kelowna solution, it was too expensive, too innovative and never given serious consideration.

Another bridge was built alongside the original in 2008; the five-lane W.R. Bennett Bridge was opened by Premier Gordon Campbell. Its namesake, former premier Bill Bennett, joined hundreds of people following the Kelowna Pipe Band to the mid-span ribbon cutting ceremony. Okanagan Lake presents unique engineering challenges for bridge builders as its bottom is unstable and changing: the W.R. Bennett Bridge is the only floating bridge in Canada and one of only eight in the world.

The new bridge was designed to accommodate traffic well into the future, though early morning reports already suggest congestion. City Park was again reconfigured, to accommodate the re-engineered approaches, and a new interchange on the west side along with a second a short way along the highway keep traffic moving on that side of the lake. In spite of attempts to streamline traffic flow through the city, Highway 97—sometimes called Harvey Avenue from pre-bridge times—is lined with a succession of traffic lights that are synchronized better some days than others. There are occasional conversations about designing another bridge and a route around the city, but it isn’t likely to happen anytime soon.

When the new bridge was built a few options were considered for the disposal of the old bridge: reusing the pontoons that were still reasonably intact, then sinking ones that were too decrepit to reuse or breaking them up for disposal. Kelowna City Council expressed interest in transforming some of the pontoons into a pier or a breakwater, but studies showed the cost of hauling them to the site and rehabilitating them would be several million dollars. The idea came to a controversial end.

It soon became apparent that no one was interested in reusing either the pontoons or the causeways at either end of the old bridge, and plans were made to sink them in the deepest part of the lake. That would have been the most cost-effective disposal method and had the least overall environmental impact. Studies revealed that nothing was growing or alive at the bottom of the lake: it was a layer of loose grey silt or clay overlain with a layer of black material, likely ash from forest fires. The biggest risk of dropping the pontoons into the lake would come from the plume of sediment that would rise as the concrete hit the bottom. Concern about polluting nearby water intakes was dismissed as residents would be notified and could take the necessary precautions. Then the public got involved, discussing unsafe levels of arsenic, chromium and nickel, and whose measurement was accurate, and whether enough samples had been taken. Eventually, the piers and pontoons were hauled to the graving dock near Bear Creek Provincial Park, where the new bridge had been assembled. They were demolished and trucked to a landfill. A few small iron girders are all that remain of the old bridge: they have been made into a curious orange sculpture that sits on the grass at the eastern end of the new bridge.

Better Air and the Remnants of Rail

Improved air service has also changed travel patterns in and out of the city: more airlines, carrying more passengers, travel to more destinations, and more frequently. Kelowna International Airport has clearly eclipsed its neighbours and has become one of the city’s most vital economic engines. It is also the tenth busiest airport in the country. Fifteen years ago about 300,000 passengers arrived and departed from the terminal each year; today, that number is closer to 1.4 million passengers. Penticton’s airport, which offered the first scheduled air service out of the valley, now serves about 70,000 passengers a year. Vernon’s airport offers charter services only.

Kelowna’s runway has been extended to handle long-haul flights from Europe and Australia, and seasonal charters offer regular service to Mexico and Las Vegas. Plans are underway to double the size of the existing terminal, add a new customs hall to facilitate international flights and improve baggage handling. A cluster of significant aviation-related businesses has also grown up around the airport. It’s a remarkable transformation from the early 1950s, when propeller-driven planes landed on a grass runway and got their instructions from the “control tower” perched on the flat deck of a truck. Kelowna’s once-struggling airport became one of the fastest-growing in North America.

The railways have all but gone except for the Kelowna Pacific Railway Ltd. which continues to provide service to the city, handling about sixteen thousand carloads of forest, grain, and industrial products a year. Only about 170 kilometres (106 miles) of mainline track remain. There are occasional quiet rumblings about restoring some form of passenger service along that line—to UBCO, or to Vernon, or to the CPR mainline in Sicamous. The comments aren’t loud but as long as the track remains, the opportunity also remains. Kelowna’s historic ties to Okanagan Lake also resonate among a few who wonder if some form of passenger travel might return to the lake in the future. As air quality deteriorates, traffic congestion worsens and gas becomes more expensive and less available, Kelowna might look to its past for solutions.

A Troubling End to the Kelowna Regatta

As Kelowna muddled through the recession of the 1980s, the legendary Kelowna International Regatta became increasingly irrelevant, and the opening of Expo 86 in Vancouver underscored just how much the entertainment world had changed. The Regatta’s bathtub races, logging shows, beer gardens and bikini parade no longer attracted families, and the event’s entire atmosphere changed. Kelowna’s first riot broke out on a hot August night in 1986. Though everyone said that Regatta wasn’t at fault and young people had been gathering downtown and drinking openly for years, the unrest broke out on the Saturday night of Regatta. People had been driven out of City Park when the carnival rides and the beer garden closed, and began gathering on Bernard Avenue. Those leaving a rock concert at Memorial Arena added to the crowd, and police stepped up enforcement as its size grew. By nine p.m. there was a very palpable sense on the street that something was going to happen. Bernard Avenue was closed to traffic so everyone abandoned their cars and congregated around the Sails. Beer bottles started flying, police reinforcements were called in from Penticton and Vernon, and the Kelowna Fire Department began using their hoses as water cannons. As tear gas began spreading through the area, windows were smashed, stores were looted and the mayor read the Riot Act. The next day, the town was in shock. Downtown store owners were furious and 105 people had been arrested. The police chief said it was “the usual crowd of idiots,” while the mayor said those involved “were just insane, like little animals… mostly punky kids too young to drink” and who should be shipped off for military training.

A new police chief and a new mayor had taken over by the following year and plans were in place to avoid a repeat of the previous year’s events. Word of Kelowna’s Regatta party had spread far and wide. Roadblocks set up outside town didn’t make much difference. Beer flowed freely as crowds gathered on Bernard Avenue and chanted, “Let’s riot, let’s riot!” Others climbed onto rooftops and threw the rocks and sticks they’d imported in the trunks of their cars. Windows were broken, stores looted, trash cans upturned and nearby residents terrified. The mayor read the Riot Act, and the crowds eventually drifted away. The police chief said the army couldn’t have stopped the destruction, and store owners were even more furious.

The rest of the 1987 Regatta carried on as planned and the event was considered a success with thirty-three thousand attending. Everyone acknowledged that the Regatta hadn’t caused the riot, but it had become a beacon for those looking for trouble, and it was subsequently noted that nothing had been planned for the fourteen- to twenty-two-year-olds, the primary age of the rioters. But no one seemed to know what to do about it. The Regatta had lost much of its community support by this time, though some thought the decline had started when the Regatta grandstand was destroyed by fire eighteen years earlier. Times had changed, and when city council cancelled future Regattas, some were outraged, some were relieved and most didn’t care.

A hardy few tried to keep the Regatta tradition alive… they called their event “the Regretta.” A parade of sorts and a breakfast were all that remained, and that only lasted for a couple of years. After eighty-two years, Kelowna had outgrown what had been its signature event, its International Regatta.

Ogopogo’s Still Around

Though the Regatta didn’t survive, the Ogopogo did. In 1983, the Okanagan Similkameen Tourist Association posted a $1 million reward for proof of the Ogopogo’s existence: acceptable proof would be a photograph or the actual monster. Greenpeace became concerned about zealous bounty hunters. When a group of young men fired their rifles at the monster from shore, the Attorney General declared the Ogopogo an endangered species under the Fisheries Act and proclaimed hunting the legendary monster illegal. In the years since, scientific and film crews from the US, Japan, Germany and Switzerland have come to the Okanagan, armed with sophisticated sonar devices and cameras, and searched around the lake monster’s reputed home near Rattlesnake Island, at Squally Point. They have occasionally seen “something” but their findings have never been conclusive. Many books have been written, many television programs have aired and the mystery remains. However, both those who believe and those who don’t agree that there is something mysterious in Okanagan Lake. Curious holes have appeared in the bottom of boats and many of those who have drowned in the lake have never been recovered. Is Ogopogo… or N´ha-a-itk… an explanation?

Mission Creek Greenway

Mission Creek begins in the Greystoke Mountains, about forty-three kilometres (twenty-seven miles) east of Kelowna, and contains almost a quarter of all the water that flows into Okanagan Lake. It was named for the mission Father Pandosy built nearby in 1859. Cottonwoods frame its shoreline, kokanee—the land-locked salmon once the diet staple of local Native communities—are slowly returning and there is hope that the meanders removed during the flood control work of the 1950s might eventually be restored. The creek has always been central part of valley life, and in 1996 a group of residents decided something had to be done to preserve it. Access to the creek channel was being encroached upon and its pristine natural surroundings were at risk of being destroyed.

The Friends of Mission Creek joined a number of user groups, including the Westbank First Nation, and began an audacious plan to create a pathway along the banks of the creek—soon to be called the Mission Creek Greenway. What started as the dream of a few mushroomed into a community-wide campaign to sell the idea, and to raise funds to buy the land and build the trails. Over six and a half hectares (sixteen acres) of land was donated, as well as almost half a million dollars: many signed on and bought a metre of trail for fifty dollars; schoolchildren took field trips, painted pictures and cleaned up the creek. Kelowna was blanketed with the preservation message as shopping centres hosted displays, raffles were held, signs appeared in buses and local businesses displayed posters in their windows. It was a remarkable campaign.

The initial seven-kilometre (four and a half mile) trail opened in October 1997, the same year Mission Creek was given BC Heritage River status. The Greenway provides a quiet, natural retreat for legions of walkers, bikers, runners and horses who use the trail throughout the changing seasons. The songs of red-winged blackbirds filter through the trees as the sound of nearby traffic gradually disappears behind the screen of pines, cottonwoods and Saskatoon bushes. The area is an easily accessible and peaceful retreat for those wanting to escape the pavement and bustle of the city.

Phase two of the popular Greenway project opened in 2005. At just less than ten kilometres (six miles) in length, this new trail is more rugged, narrower and more challenging that the first phase of the project. It features a wetland boardwalk, three pedestrian bridges and stairs below the Gallagher’s Canyon Golf Course. The views of some of the area’s most unique geological features are spectacular as the trail winds through Scenic Canyon Regional Park and past Layer Cake Mountain, a 200-metre (650-foot) layered rock face formed millions of years ago by cooling lava. It continues on past Pinnacle Rock and the Hoodoos, the glacial deposits that line the canyon escarpment. Cave-like openings at the bottom of the high rock wall are the only evidence of the Chinese fortune-seekers who panned the sand and gravel deposits for gold over a century ago. Interpretive kiosks tell of the area’s rich history and unusual features while a viewing platform and trail guides add to the amenities.

Phase three of the Greenway is now being planned, and will stretch from KLO Creek to the beautiful and currently inaccessible Mission Creek Falls. The Greenway is a remarkable achievement for a dedicated group of volunteers whose efforts transformed the dikes of Mission Creek into a unique community asset.

The Okanagan Mountain Fire

In 2003, an epic wildfire raged along the east side of Okanagan Lake and into the forest and residential neighbourhoods south of Kelowna, an area known as the South Slopes. Fire had ravaged the community before and residents had long been familiar with smoky air during the summer forest fire and orchard-burning seasons. But this was different. People watched in fascination as a small fire ignited by an early morning lightning strike spread across the dry mountainside. When it started across from Peachland at Squally Point, in Okanagan Mountain Park on the east side of the lake, the fire seemed a long way away. Everyone expected it to be contained. Over 240 wildfires were burning in the Southern Interior at the time and the Forest Service felt their crews and equipment were needed elsewhere. People took their lawn chairs to the beach and watched the smoke billow and glow in the setting sun. Record-breaking heat had blanketed the valley for weeks and the forests were already parched from the lack of rain: the result was almost inevitable. When the wind picked up, the layers of dry needles and leaves sucked in the flames, and then flared up all along the mountainside.

Over 1,000 hectares (2,400 acres) were burning within a day. The fire grew from 2,000 to 11,000 hectares (5,000 to 27,000 acres) in another day and raced along the dry rocky hillside. A fire break seventeen kilometres (ten and a half miles) long was built along Kelowna’s southern boundary, but the flames flared up the trees and leapt across. Trees candled as their sap boiled and they too exploded into flame. Everyone expected it would stop: the sun shone as residents raked the needles under their pines, put sprinklers on their roofs and carried on with their usual summer activities. Bard on the Hill was performing Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the amphitheatre of Mission Hill Winery on the west side. The actors had to compete with the smoke and the audience’s fascination with the flames advancing along the hill—they were across the lake but seemed so close. The smoke swirled and engulfed the performers and the audience.

The wind had split at Squally Point and carried the flames northward toward Kelowna and southward to Naramata. The fire kept advancing and the first of what would become a series of evacuations was ordered for both communities. Many had little warning: the question everyone was asking was, “If you had to evacuate, what would you take?” In the panic some chose lamps and mattresses while others grabbed their animals, leapt into their cars and left their front doors open in the rush. Kelowna’s fire department was familiar with structural fires but this was a whole new experience: smoke often screened the flames and obscured escape routes. Against advice, some lakeshore owners stayed behind to do what they could to save their homes, though most kept their boats nearby in case they needed to leave in a hurry.

People were drawn to the beaches to watch a succession of water bombers fly over Okanagan Lake Bridge, one after the other, dipping to skim along the lake’s surface, fill their tanks and head back to drop their loads just minutes away. More evacuations were ordered and those fleeing often ended up stuck in traffic; horses, cows and chickens were rescued and moved to secure farms; people stayed with friends and used binoculars to see if their homes were burning. At one point, thirty thousand people were ordered to leave their homes: some returned only to be told to leave again.

Wildfires are so unpredictable, and sound like a jet revving up to take off. They create their own wind patterns and change direction with a turn in the road, a clump of trees or a gully: this house survives while the one next door doesn’t. The Okanagan Mountain Fire was no different. The plastic garden furniture on one patio survived while the house right next to it was gone. Stones shattered; a boat stored in a garage became a puddle of fibreglass; flames would encircle and then miraculously retreat. The fire was so intense in other places that a mound of fine dust might be all that remained of a house and its contents.

The army arrived. Firefighters converged from across Canada and the US. Evacuation centres were set up as chunks of still-hot ash floated over the city. Fire Chief Gerry Zimmerman held regular media briefings to keep evacuees, the media and everyone else up to date. When asked if there was anything he needed, he jokingly said a cold beer would be nice... and it wasn’t long before a refrigerated truck loaded with beer arrived at the fire hall. CedarCreek Winery built a firebreak, while St. Hubertus burned to the ground: smoke permeated both wineries’ ripening grapes and they couldn’t be used. In one night, 223 houses vanished.

When the wind died down, firefighters went looking for hotspots in tree roots and deep in the debris-covered forest floor. Then the wind returned and blew the fire up the hillsides into Myra Canyon and the surrounding area. In all, the fire took just over two weeks to destroy more than 25,000 hectares (62,000 acres) of forest and parkland and 239 homes. An inquiry followed, and when wildfires are spotted now, the response is immediate: water bombers, fire retardant and firefighters are on the scene in minutes.

The Kettle Valley Trestles

Although the Kettle Valley Railway (KVR) was never intended to be Kelowna’s railway, the city has claimed the stretch of roadbed, trestles and tunnels above Okanagan Mission as its own. Now part of the Trans Canada Trail, the KVR not only draws local hikers and mountain bikers, but also tourists who arrive from all over the world to travel the awe-inspiring historical remnant. Myra Station, which is named for the daughter of a track-laying foreman (it’s the first of the “daughter” stations), is Kelowna’s access to the most scenic part of the old railway. Ruth and Lorna Stations—named for the daughters of Andrew McCulloch, the railway’s chief engineer, and James Warren, president of the KVR system—follow, but no station buildings remain at any of the sites.

Myra Canyon is rocky and has numerous steep gorges along its sides, carved by creeks. The line’s highest elevation, 1,260 metres (4,133 feet) above sea level, is just before the first tunnel while the lowest, 349 metres (1,145 feet), is at the Penticton terminus. It was challenging terrain to build a railway as it was essential to keep the grade under two percent to ensure efficient operation of the railway. Andrew McCulloch referred to Myra as that “damn bad canyon,” increased the grade slightly and built a track that doubled back on itself not once, but twice, by adding a curved tunnel through a rock face, plus another tunnel, and building twenty wooden trestles. The Myra Canyon stretch of the KVR remains an engineering marvel in the annals of railway construction. It also makes for a relatively easy hike or bike ride through the wilderness, with spectacular views of Okanagan Lake.

Many changes have been made over the life of the rail line. The original trestles and tunnel supports had a life expectancy of about fifteen years. By the time the last train crossed the tracks in 1972, two trestles had been replaced by steel bridges while the remaining trestles were fourth-generation wooden ones. The last replacements had been built in the mid-1950s and treated with creosote in hopes of doubling their lifespan.

The BC government acquired the track right-of-way and lifted the rails in 1980. The trestles remained in place but the ties deteriorated: some were missing and others were vandalized. The adventurous were undeterred and continued to drive cars across the trestles and carry their own boards to lay across in place of the missing ties. Others hiked or biked across and around the increasingly hazardous trestles and made their way through the rock-filled tunnels. A death and several serious injuries soon had the government calling for the area to be closed to the public.

An enthusiastic group of volunteers formed the Myra Canyon Trestle Restoration Society in 1992 to repair the trestles and make them both more accessible and safer. Two years later, a boardwalk crossed each trestle with guardrails along each side, all as a result of volunteer labour, scrounged materials, borrowed equipment and a few donated dollars. The group went on to repair the trail bed and the tunnel portal, and then removed some of the collapsed rock from inside the tunnel. Over fifty thousand visitors flocked to the area by the late 1990s, which soon became one of the top fifty biking destinations in the world. It took a few years, but the canyon eventually became part of a new Myra–Bellevue Provincial Park. The trestles were added to the National Historic Sites register in 2003 and the route became an important link in the Trans Canada Trail.

Seven months later, twelve of the sixteen wooden trestles were destroyed by the Okanagan Mountain fire. Even water bombers dropping fire retardant on the trestles couldn’t stop the devastation. The winds changed and towering flames could be seen along the hillside as the succession of the old creosote trestles were engulfed in flames. It was a demoralizing blow, even for those who had never been near the old rail line.

Because of its provincial and national importance, disaster relief funds became available and a number of those who worked on the original restoration became part of the Myra Canyon Reconstruction Project. Their goal was to rebuild the trestles to resemble the originals as closely as possible. Bridge builders gathered from around the province, large Douglas firs were brought from the Lower Mainland and by a year after the blaze, the first trestle had been rebuilt. A few more were restored during each of the next four years, and in 2008 the area was again accessible to the public. At the opening celebration, bagpipes led “Andrew McCulloch” and a joyous and unexpectedly enormous crowd along the restored railbed and through the tunnels. The rebuilding of the trestles became symbolic of the area’s recovery after the devastating fire, and the Kettle Valley Railway finally, after many years, truly became Kelowna’s railway, and one of the city’s most popular tourist attractions.

A Hockey Revival

Organized hockey has been the centrepiece of Kelowna’s sports scene since the early 1950s. The original Kelowna Packers were followed by the Buckaroos, the Wings, another Packers team, and the Spartans. Memorial Arena was home ice for all of them, but it became harder over the years to sustain the franchise and entice fans to fill the arena’s 2,600 hard seats. The promise of a new arena enticed the Rockets of the Western Hockey League to leave Tacoma, Washington, and relocate to Kelowna. The only trouble was that the referendum to build the rink was defeated and the team had to play in the old Memorial Arena, until a partnership with a private developer resulted in the building of the six-thousand-seat Skyreach (now Prospera) Place. Built on what had earlier been part of the CNR marshalling yards, the arena opened in 1999 as the home of the Kelowna Rockets.

The Rockets drew Kelowna residents back to the hockey rink when for three straight years (2003, 2004 and 2005) they qualified to play in Memorial Cup tournaments. The cup is awarded annually to the Canadian Hockey League (CHL) junior ice hockey club that wins the round robin tournament between the host team and the champions of the CHL’s three member leagues. The Rockets won the Memorial Cup for the first time in franchise history in 2004, the same year they were selected to host the event. Every game in the tournament was sold out and the whole city celebrated their team’s victory. In 2009, and for the fourth time in seven years, the Kelowna Rockets qualified again to play in the Memorial Cup. Though the team was defeated by the Windsor Spitfires in a tournament held in Rimouski, Quebec, a loyal hometown fan base continues to fill Prospera Place throughout the season.

The multipurpose building is also used for various community events including monster truck shows, roller derbies, craft shows and figure skating performances. Cirque du Soleíl, Elton John, Harry Belafonte and Sarah McLachlan are among the various artists who perform in the venue. Though limited to eight thousand concert seats, Kelowna’s Prospera Place is a popular choice for many artists travelling between larger venues in Calgary and Vancouver.

The Simpson Covenant

In the early summer of 2008, Tom Smithwick, legal counsel for the Save the Heritage Simpson Covenant Society, prefaced his final argument in the BC Supreme Court with the words: “Your Worship, we should not be here today.”

The story began in the mid-1940s when the City of Kelowna was looking for property large enough to build a city hall and house other civic services. Stanley M. Simpson had purchased the old Kelowna Saw Mill from David Lloyd-Jones in 1942, and continued to run the mill until it was destroyed by fire in 1944. The sawmill had had sheds and wharves along the lakeshore north of Bernard Avenue since the late 1800s, while old buildings and piles of lumber and sawdust were scattered across another 16 or so acres that extended eastward to Ellis Street and northward to near today’s courthouse. The city approached Simpson to see if he would sell them the land.

Though he had postwar plans to locate a new type of building supply store at the foot of Pendozi Street (the present location of the Bennett Fountain), S.M. agreed to sell the land to the city, under specific conditions, which he attached as a covenant on the land. The initial agreement was for seven-plus acres, but it wasn’t long before the lakeshore portion, across the street from the original parcel, was also included.

The covenant specified that the land could only be used for civic purposes, for the use and enjoyment of the citizens of the city, not commercial or industrial use, and that it could never be sold. The sale was conditional upon the city accepting the terms of the covenant. Council held a referendum to approve the expenditure of $55,000 to purchase the roughly eleven and a half acres of land, a price that was acknowledged at the time to be well below the market value of the property. The citizens approved the expenditure, and the terms of the covenant had also been well publicized. There was both an implicit and explicit awareness of the terms of the Simpson Covenant during a succession of municipal administrations.

The covenant was never questioned until 2002, when a developer proposed the construction of a cluster of high-rise condos on the waterfront, at the foot of Queensway Avenue. The plan encroached on approximately one third of the city’s lakeshore property. City staff approached Stanley Simpson’s descendants, who continue to live in Kelowna, in an effort to get their agreement to change the boundaries of covenanted land. Many meetings, over several years, ensued with various Simpson family members. The family would not, nor did they feel they had the right to agree to any changes to the original agreement.