Chapter Two: Discovering the Okanagan

The wave of change that followed the completion of the CPR’s transcontinental railway was being felt in the Okanagan by 1890. Rumours of a branch line through the valley encouraged investors to buy acreage along the railway’s most likely routing. BC’s mountainous terrain dictated that wagon roads and railroads generally ran east-west, while north-south travel could take advantage of the area’s abundant river systems and lakes. Sternwheelers had been running freight and passengers on the Fraser River since the mid-1850s, and steam had been introduced to the Kootenay Lakes by the mid-1880s, so it wasn’t long before boat traffic began to increase on Okanagan Lake. Settlers had been rowing themselves and their supplies up and down the lake for years, but steam would soon replace muscle. The Okanagan Valley was once again about to undergo a major transformation.

The Real Estate Boom

Rumours and speculation flooded the region in the early 1890s with talk of new railroads, larger boats and new towns. It wasn’t long before the valley’s first real estate boom became a reality. The British and several of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy were discovering Canada’s west and many, including the Vernon brothers, came with capital to invest, influential contacts through which to attract more and a lifestyle they intended to preserve. Change started at the northern end of the valley in about 1887, when the townsites of Centreville and Priest’s Valley were collectively renamed Vernon, after Forbes George Vernon, owner of the nearby Coldstream Ranch. Vernon was a man to be reckoned with, as he was also a member of the provincial legislature and chief commissioner of lands and works.

The Shuswap & Okanagan Railway was incorporated in 1886 with a mandate to connect the CPR mainline at Sicamous with Vernon, and then continue on to Okanagan Lake at Okanagan Landing. The CPR was its dominant shareholder and while construction took some time to get underway, the track was complete enough by 1892 that a slow train was able to reach Vernon. In that same year, the Okanagan Land Development Company laid out the new townsite, built the Coldstream and Kalamalka hotels, installed a water system and published the Vernon News. Two of that company’s principal investors were Forbes George Vernon and George Grant MacKay, the well-connected Vancouver land promoter who knew of the valley’s fruit-growing potential from his fellow director at the BC Fruit Marketing Board, Alfred Postill.

The Okanagan Land and Development Company placed an advertisement in its newspaper at the end of 1891 touting Vernon as the gateway to the Okanagan, Nicola and Similkameen Valleys, as well as the mining camps of Rock Creek and Keremeos. Rumours were rampant that a Vernon & Okanagan Railway would soon be built through the Mission Valley to Penticton and connect the CPR with the Great Northern Railway in the US. Vernon was sure to become the area’s natural marketplace and supply headquarters as settlers arrived to take advantage of the abundant fruit growing, ranching and mining opportunities. Prospective land purchasers were invited to come in person, meet with the company’s local representatives and be introduced to the community’s unlimited potential.

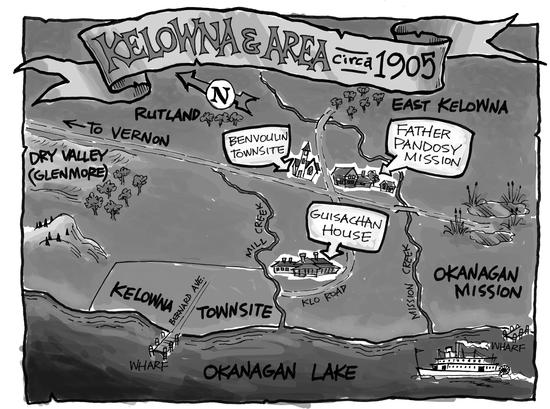

With Vernon established, G.G. MacKay was certain the rumoured railway running through the centre of the valley would be the next best development opportunity. It wasn’t long before he laid out a new Benvoulin townsite. It was at the intersection of the wagon roads between the Catholic Mission and Vernon, and the westerly road to Knox’s wharf at the base of the mountain (today’s intersection of Benvoulin and Byrns Roads). MacKay signalled the settlers he hoped to attract by donating land for a Presbyterian church, which would be the first Protestant church in the Mission Valley. (The one on Richter Street would not be built until 1898.) The new townsite soon grew to include a blacksmith shop, a Chinese laundry, a general store and a ten-room hotel painted yellow with a mixture of oil and the ochre found in Mission Creek. MacKay called his new town Benvoulin because of a similar valley view near Oban, in his native Scotland.

Royalty Discovers the Okanagan

Among the well-connected Scottish aristocrats interested in Canada were Lord and Lady Aberdeen, who arrived in Vancouver in 1890 as part of their cross-Canada rail tour. John Campbell Hamilton Gordon, the Seventh Earl of Aberdeen (and later First Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair), had succeeded to his title after the untimely death of a brother. His wife, Ishbel Maria Marjoribanks (pronounced Marshbanks), was the daughter of the first Lord Tweedsmouth. They were both from prominent families and part of Queen Victoria’s colonial administration: the earl had been appointed Lord Lieutenant of Ireland before serving as Canada’s Governor General from 1893 to 1898.

Their trip had been designed to give Ishbel a rest from her demanding commitments to various social and political causes at home, and the recurring bouts of nervous exhaustion that plagued her for much of her life. Never one to let an opportunity pass, Ishbel also wanted to check up on some of the British girls who had been sent to the colony by one of her charitable organizations; such emigrations were seen as a good way to deal with the social problems plaguing industrial Britain, as well as to ensure the colony was populated with the “right” sort of people. The Aberdeens had already decided to purchase a holiday retreat in Western Canada and with Lady Aberdeen’s brother, Coutts, in need of a job, he would be available to manage it for them.

Shortly after their arrival, the viceregal couple re-established contact with George Grant MacKay, who had been the engineer in charge of building roads at Lady Aberdeen’s ancestral home in Inverness-shire. MacKay had been in Vancouver about three years by the time the Aberdeens arrived and was well established in the real estate business. The viceregal couple had little time to look at property during their short stay but decided MacKay’s first suggestion of the Fraser Valley, at fifty to sixty dollars an acre, was too expensive.

MacKay’s next suggestion, a little farther away, was the Okanagan Valley. He knew the area not only because of its fruit-growing potential, but because he had already bought three thousand acres of land along the rumoured railway’s most likely route. These lands included many of the originally pre-empted acres, whose owners were both aging and weary of the struggles of the past decades; they were also likely surprised anyone wanted to buy their land. This suggestion was more to the Aberdeens’ liking, and before the viceregal couple left Vancouver they had engaged MacKay to act on their behalf and purchase property. The 480-acre McDougall homestead half a mile or so from Father Pandosy’s mission had already been purchased by MacKay; he resold to the Aberdeens for ten thousand dollars. A rough though functional house was already on the property and the sale included seventy head of cattle, horses and other livestock, plus wheat and farm implements. MacKay’s assurances that a new railway would soon be built through the area, and increase property values at least tenfold, further enticed the couple to purchase the property, sight unseen.

The farm was a perfect opportunity for Ishbel’s brother, the Honourable Coutts Marjoribanks. Coutts was a remittance man—one of those young English men, often the second or third sons of British nobility, who didn’t inherit the ancestral property, didn’t seem much attracted to the church or the army and for whom a career in business was simply unsuitable. Many of these young men were sent off to the colonies to earn their keep or, at the very least, not embarrass the family. Each Marjoribanks son was sent to the New World and given a cattle ranch: Archibald the 200,000-acre Rocking Chair Ranch in Texas, and Coutts the 960-acre Horse-Shoe Ranch in North Dakota. They also each received remittances of four hundred pounds a year. Neither son knew much about raising cattle or running a business, though both were genial and popular—especially in the neighbouring saloons, when their money arrived. It wasn’t long before both ranches were up for sale.

It didn’t take Coutts and his friend and new ranch manager, Eustace Smith, long to vacate their old ranch and head north for a new adventure. The old farmhouse was far too primitive for the Aberdeens so the pair had a new elegant clapboard ranch house built, patterned on the style of an East Indian cottage and complete with gold Japanese wallpaper, seven chimneys and a wraparound veranda. The ranch was soon called Guisachan, after the Marjoribanks’ ancestral home in Scotland. Once the house was finished, the two men felt their job was done and set about enjoying valley life, filling their days with hunting expeditions and visits to the various saloons.

The Aberdeens returned to British Columbia in the fall of 1891 and made their first visit to the Okanagan. The Shuswap & Okanagan Railway was still a work in progress and the Aberdeens had to pay seventy-five dollars (later negotiated to half by his lordship) to hire an engine to pull their passenger car; two luggage cars loaded with a motley collection of men, dogs, parcels, trunks and agricultural machinery; and a caboose. The train moved so slowly that the party was able to clamber off and walk alongside the engine; other times they had to climb on board as the train crossed bridges still being worked on by large gangs of men.

The party finally arrived in Vernon, where they were met by Coutts, who had been enjoying himself for a week as he waited for the couple: old-timers remember Coutts riding his horse up the stairs of the Kalamalka Hotel and into the commodious bar for a drink. The Honourable Mr. Forbes Vernon had been scheduled to greet the couple and open the Vernon Agricultural Fair, but had been detained in Victoria. Lord Aberdeen took his place and was delighted to declare the Vernon Fair officially open. It was a grand occasion for the Aberdeens: they met many important people from all over the Okanagan and renewed their acquaintance with George MacKay, who was in town to buy more of the old Mission ranches. He had already begun to subdivide them into forty- to sixty-acre lots to sell to the settlers he was hoping to attract to the valley.

The viceregal party dallied so long at the fair that the small steamer that was to carry them down the lake to their Guisachan property had already departed by the time they were ready to go. The crews of other boats had all decamped for the ball and festivities in Vernon, so the party was left to accept Leon Lequime’s offer to take them south. His little boat was not equipped to carry passengers but the party appeared undeterred as they crowded into its makeshift cabin and sang their way through much of the four-hour moonlit trip down the lake.

The Aberdeens and their party landed near the Mission wharf very early in the morning, walked the two miles to Guisachan House and startled the ranch manager: not expecting anyone, he opened the door with shotgun in hand. While Foo, the Chinese cook, prepared a meal, the family admired the bachelor manager’s handiwork: stag horns and deer heads were mounted on the gold wallpaper, the large sitting and dining rooms were well furnished, as were the six bedrooms, and the kitchen and office were separated by the veranda that encircled the house.

This was the first time the Aberdeens had visited their new property and their arrival in the dark of night did nothing to dispel their expectation of flat plains and bare hills. They were delighted when the morning light revealed that their property looked more like Scotland than they could have imagined. Woods surrounded the house, the lake was off in the distance and pine trees covered the nearby hillsides. The autumn-gold poplars and cottonwoods along the banks of Mission Creek added to the charming vista.

The Aberdeens stayed for a full and busy week. They went on a bear hunt with a group of locals (though only shot prairie chickens), they donated four hundred dollars to help build the new Benvoulin Presbyterian Church, enjoyed a picnic at Long Lake (Kalamalka Lake) and visited Alfred Postill and his mother for tea. They also hosted a social—an unusual event in this unsophisticated community—where guests performed songs and recitations and the Aberdeens’ daughter, Lady Marjorie, sang three French songs to much acclaim. Tea was then served and Lady Aberdeen brought the event to a close with two readings. A few days later, the family held an informal church service in their living room and were surprised by the arrival of the Mission priests, who seemed much pleased with Lord Aberdeen’s words.

The Aberdeens were soon convinced that the Okanagan showed great promise as a fruit-growing centre. Hoping to attract a good class of settler, Lady Aberdeen noted that orcharding would be a “delightful occupation” for those with capital to invest who could also provide the good influences and high moral tone so needed in the area. They led by example and soon had two hundred acres of their property planted with apples, pears, plums, cherries and peaches. Strawberries, raspberries and blackberries were set between the trees to provide a more immediate cash crop. Lady Aberdeen also mused that a jam factory would be a great addition to their farm as it could surely produce jams to rival those produced by Crosse and Blackwell, her favourite English brand. (Hers would be sold as “The Premier Preserves manufactured from the celebrated Okanagan Orchards.”)

It was a whirlwind visit and the Aberdeens were on their way back to Scotland a few days later, on October 24, 1891. But the lord and lady were so enchanted with their time at Guisachan they instructed George MacKay to find them additional property. MacKay and Forbes Vernon were still partners in the land development company, and MacKay knew Vernon was interested in selling his thirteen-thousand-acre Coldstream Ranch. It was an obvious choice for the Aberdeens. They wasted no time and a week after departing from their first visit to Guisachan the Aberdeens had purchased the larger property, plus two thousand head of cattle, seventy horses, farm implements, hogs, hay and furniture. Coutts soon moved north to manage the new ranch. A second home was built for the family on the Coldstream property and the Aberdeens rarely visited Guisachan again, and never stayed at the house.

It was three years before the Aberdeens were able to visit their new property. By then, Lord Aberdeen had already been Canada’s Governor General for a year. Lady Aberdeen’s jam factory was built at the Coldstream Ranch. No jam was ever produced, but the building became the perfect setting for the couple’s grand balls. The Aberdeens owned Guisachan until 1903, when it was sold to the Cameron family. They last visited the Coldstream Ranch in the winter of 1915–16; Lord Woolavington, who had joined the Aberdeens as a business partner, assumed ownership of the property in 1921.

Among Lady Aberdeen’s many attributes was that she was a prolific journalist. Through Canada with a Kodak, published in 1893, the same year Lord Aberdeen became Governor General of Canada, told the story of the couple’s first train trip across Canada. The Kodak camera had recently been invented and Ishbel included a number of photographs, along with several of her own sketches, in the book. With her well-developed social conscience, formidable organizing talents and political astuteness, she was also a force to be reckoned with. Lady Aberdeen established the National Council of Women (including a chapter in Vernon), the Victorian Order of Nurses and the May Court Club (Canada’s oldest women’s service organization) during the brief time she was in Canada; in fact, she sometimes overshadowed her quiet husband and is known in some circles as Canada’s Governess General.

Though the Aberdeens’ agricultural endeavours were never a financial success, the couple’s willingness to visit, to invest in the land, to build homes and to encourage others to join them put the Okanagan on the British Empire’s map. In particular, their belief in the valley’s fruit-growing potential attracted immigrants and it wasn’t long before the Okanagan became one of the most sought-after destinations in the empire. The Aberdeens’ appeal to British settlers set the stage for most future immigration to the valley, though a few settlers of other nationalities, already homesteading on the Prairies, were also drawn to the area’s benign climate. The romantic notion of planting orchards and then sitting back and reaping the benefits was certainly attractive, though many who bought into the Aberdeens’ vision soon realized that much more effort was required.

Earliest Kelowna

G.G. MacKay’s arrival in the Mission Valley seemed to roust the old-timers from their lethargy. The two remaining Lequime brothers, Bernard and Leon, were among the few early settlers who had enough money to expand their holdings. They bought Auguste Gillard’s original pre-emption in 1890. It was a logical choice as the property shared a common boundary with theirs as well, and Gillard’s included a workable slice of Okanagan lakeshore.

The Lequime sawmill had been packing lumber to settlers up and down the valley for a number of years, but with increased traffic on Okanagan Lake the advantage of having ready access to the waterway was becoming more apparent. In 1891 the brothers dismantled their mill on the bench above their Mission property, packed up what was salvageable and reconstructed it on the lakeshore of their new property. The main building was a ninety-two-foot-long sawmill, the second a forty-five-foot-long planing mill, and there was a dry kiln housed in a separate building. Just north of the sawmill, a sixteen-by-forty-foot boarding house was built for men working at the mill. Over time it became known as the Grand Pacific Hotel and also began welcoming travellers passing through town. A Chinese cook prepared meals in a nearby lean-to cookhouse and a painted sign inviting people to “Eat and Flop” remained visible on the side of the building for many years.

When the Lequimes purchased Gillard’s property, a townsite plan had already been prepared but not registered; Bernard saw to this in August 1892. Earlier that year Bernard had commissioned J.A. Coryell, C.E. and Company, surveyors from Vernon, to lay out the approximately three-hundred-acre townsite, and placed an advertisement in the Vernon News to say that the new town would be called Kelowna. There are a number of versions of the story about how Kelowna got its name, but it is generally agreed that on one cold winter day, Auguste Gillard, the original owner of the land who lived beside the creek at the south end of today’s Ellis Street, was seen climbing up the ladder of his kekuli (or kickwillie), an Indian pit house built half below the ground and half above, with a rough timber roof and an access ladder extending up through the smoke hole. A passing group of Natives heard a great commotion coming from inside the dwelling and stopped to stare as a large hairy creature backed up the ladder. It being winter, Gillard had cut neither his hair nor his beard, and the Natives, thinking he was a bear, called out Kemxtu´h, Kemxtu´h—or “Kim-ach-touch, Kim-ach-touch”—meaning “brown bear, brown bear.” The name stuck with Gillard for many years. Some of the old-timers thought “Kimachtouch” would be a great name for the new town, but Lequime wasn’t convinced—he thought it might be awkward for those not familiar with the Native language. However, when “Kelowna,” the Native word for grizzly bear, was suggested as an alternative, Lequime was more agreeable and undeterred by the fact that Natives traditionally did not name places after animals.

In addition to announcing the townsite and its new name, Bernard Lequime placed another advertisement in the same issue of the Vernon News, offering lots for sale in “The Garden Town of B.C. and the natural shipping and distributing point for the fertile Okanagan Mission Valley.” The rivalry between Vernon and Kelowna had begun. Lequime seemed naively optimistic that his Kelowna townsite would prevail over Benvoulin.

George MacKay returned to the Mission Valley late in 1892, still certain that construction of the new rail line was imminent. It would be his last visit, as the Okanagan’s first great real estate promoter passed away at his home in Vancouver a few weeks later, at the age of sixty-seven. MacKay had only been in Canada five years and had already made a profound impact: in Vancouver he was known as the “Laird of Capilano” for constructing the first suspension bridge across that canyon. He had arrived in the Okanagan and instigated the break-up of the valley’s large cattle ranches into orchard-sized properties. His introduction of the Aberdeens to the Mission Valley was a timely stroke of genius: they became his most enthusiastic and influential ambassadors and spread word of the Okanagan around the British Empire as few others could have done.

Bernard Lequime was among the few who didn’t buy into MacKay’s sales pitch and remained convinced that Okanagan Lake would be the preferred travel route in the future. Lequime built a wharf and a freight shed in the nearby bay (now the north-facing beach in City Park) and soon became the sole owner of the lakeside sawmill. Not long after, he was plagued by a series of fires: the dry kiln caught fire three times in the first year of operation; another fire soon destroyed the sawmill, planing mill and nearby piles of lumber. Only the great efforts of a bucket brigade saved another 200,000 feet of lumber piled a bit farther away from the plant. Insurance wasn’t an option, and Lequime financed the reconstruction himself. The business was likely profitable, however, even though it operated only during the warmer months of the year and usually only employed about twenty men.

Though Leon Lequime left the sawmill business, he joined Bernard to create the Lequime Bros. General Store which opened across the dirt road from their sawmill. The new store, built by newcomer David Lloyd-Jones and measuring twenty-six by forty-five feet, catered to the lake trade. (The brothers also continued to operate their family’s Mission store, which Eli, their father, had opened thirty years earlier.) A few months later, the store became Lequime Bros. & Company when Clinton Atwood and Edwin Weddell became partners in the business. They advertised in the Vernon News, stating that Lequime Bros. & Co. of Kelowna carried “the best stock in the country” and assuring the people of the district that their prices compared “with any in the Valley.” The stock consisted of dry goods, boots and shoes, crockery, glassware and groceries, all new and well bought.

Dealing with Ogopogo

As settlers began to travel Okanagan Lake, the Ogopogo became a fearsome reality in their lives. The creature began life in the legends of the Okanagan people as N´ha-a-itk (or Naitaka), a lake monster that was both revered and feared. The monster was said to be the embodiment of an evil wanderer who murdered a kindly old man and was cursed with having to spend eternity near the scene of the crime. Pictographs of the creature were found on the rock bluffs above the lake, and early stories tell of the need to appease the monster by offering small animal sacrifices. Those who ignored the warning or didn’t show the proper reverence would all too often be caught in a wild and unexpected storm. Among N´ha-a-itk’s victims was the young Chief Timbasket, who scoffed at the stories, paddled too close to the monster’s home in the caves around Squally Point (across the lake from present-day Peachland) and was suddenly sucked under in a great swirl of angry waves. He and his family members vanished. Some time later his canoe was found far up the mountainside, farther than any wave might have thrown it… had N´ha-a-itk devoured the chief and flung his canoe away in anger?

Early settlers knew to respect the turbulent, unpredictable lake, but also knew the Native legends. They told stories of paddling across the lake with their horses tied behind canoes, when the horses would inexplicably be drawn down and down by some strange force from below. The once-sacred monster turned into a demon as early settlers patrolled the lakeshore, musket in hand, to protect their families. Other times, great slabs of meat were stuck on large iron hooks and set out in the lake to trap the creature.

Descriptions vary, though most of those reporting sightings agree that the monster is a curious aquatic species. Its appearance hasn’t changed much over time—the eyes are bulging, and it is dark green or shiny black—though its early snake-like head has evolved into something more horse- or sheep-like. Its early upright ears have also become tiny horns. Perhaps there is a forked tail. Its long slim body, usually between thirty and seventy feet in length, is seen as two or three or more humps above the water. The creature has been seen moving against the wind, though it is most often sighted as a swell in a calm lake when no boat or debris is in sight. It moves too fast to be a swimmer and leaves a wake that washes up on the beach a few minutes later.

The Admiral of the Okanagan

The wave of change created by the completion of the Canadian Pacific’s transcontinental railway slowly found its way into the Okanagan. By this time, the Shuswap & Okanagan Railway carried passengers from the transcontinental train through Vernon and onto the lakeshore at Okanagan Landing. Rumours of the next likely branch line were rampant as various companies were laying tracks across the international border, over mountain ranges and into mine sites. Everyone was certain the Mission Valley line was inevitable. Yet the geographic reality of the east side of Okanagan Lake, with its deep canyons and steep mountainsides, conspired against any such plans: no rail line would ever materialize. Although the idea never entirely disappeared, the arrival of the lake steamers soon pushed talk of it aside.

Captain Thomas Dolman Shorts was the first of many enterprising individuals to travel the length of Okanagan Lake by boat. He whipsawed lumber, built a twenty-two-foot-long rowboat, calling it the Ruth Shorts, after his mother. The boat could carry two and a half tons of cargo, accommodate a few passengers and hoist a sail if wind and weather permitted. There was nothing scheduled or ordinary about travelling with the captain. Shorts didn’t like to be tied down so he departed when he felt like it, or when there was enough business to warrant the effort. He rowed during the day and would pull up to a beach at dusk, where he and his passengers would sleep under the trees for the night. If the weather took a turn for the worse he would head for land. Even the most fragile governess travelling to join a new family at the south end of the lake had little alternative but to join the captain and camp out until the weather improved. If Shorts travelled in a straight line, the trip between Okanagan Landing and Penticton was about sixty-five miles and took about nine days of rowing—if the weather was fine. If the weather was bad, it took as long as it took.

Shorts soon moved on to steam power and built the thirty-five-foot Mary Victoria Greenhow in about 1884. He could now carry five tons of freight and several passengers, and he used kerosene as fuel. The maiden voyage wasn’t a great success as the captain had underestimated the amount of fuel he would need and was forced to resort to his oars several times, begging or borrowing more kerosene along the way. His arrival in Penticton was celebrated with a twenty-one-shotgun salute—no cannons were available. After acknowledging the tribute, Shorts refuelled and headed back north. The Lequime store at Okanagan Mission was his next supply point: he beached the boat and walked across the fields to the store. On his return, Shorts discovered that fire had destroyed most of his boat, though fortunately not enough to prevent him from returning to Okanagan Landing.

Shorts wanted to change the engine to burn wood, so he removed it, made revisions and, in 1887, installed the converted engine into the hull of the new thirty-foot-long Jubilee. Named in honour of Queen Victoria’s fifty years on Britain’s throne, this boat could tow a barge—which was a bonus, as the volume of freight heading to Penticton for the nearby mines had increased significantly. The engine continued to have an insatiable appetite, however, and Shorts had to arrange for cord wood to be stacked along the shoreline on both sides of the lake. Even these reserves were often not enough, and Shorts continued to run out of fuel regularly; on one trip he was forced to feed his cargo of cedar shakes into the boiler so he could reach his destination. The Jubilee lasted for two years: the winter of 1889 was particularly cold and when the ice finally thawed around its berth at Okanagan Landing, the boat promptly sank.

Not having the funds to improve or expand his fleet of one, the ambitious Shorts convinced pioneer South Okanagan rancher Tom Ellis to invest in his next venture. The new boat would be his largest yet, but it would take some time to build. Shorts couldn’t afford to be sidelined during its construction, however, so he salvaged the engine from the Jubilee, attached it to a scow and called the result the City of Vernon. No one had a kind word to say about the aberration but it kept him in business. When the new boat was finally ready, Shorts christened it the Penticton. Though it was intended to carry passengers as well as freight, Shorts still wasn’t into luxury: the Penticton’s cabin could hold twenty-five people, but it contained only one chair—first come, first seated. And there was still no semblance of a schedule—the good captain sailed when he felt like it. The City of Vernon was sold and renamed the Mud Hen because it spent more time at the bottom of the lake than on the surface. Remarkably, the engine was again salvaged and installed in the Wanderer, later known as the Violet. Today, the engine is on display at the Vernon Museum.

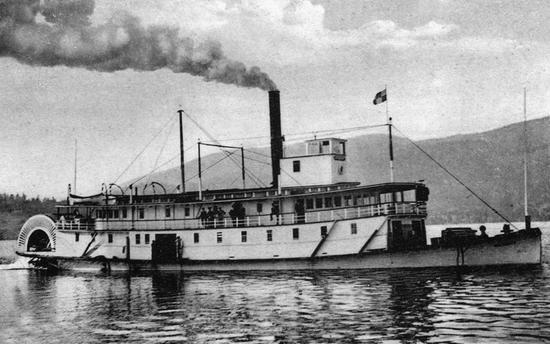

Leon Lequime bought the Penticton from Shorts and Ellis in 1892. He paid the hefty sum of five thousand dollars for the boat and then negotiated a contract with the CPR to meet the Shuswap & Okanagan Railway at Okanagan Landing and deliver passengers and mail to their various destinations. Since Okanagan Lake froze over again that winter, the 1892–93 boating season was short. The CPR had also begun to build its first sternwheeler, the SS Aberdeen, at Okanagan Landing. Leon continued to operate the Penticton for a number of years, including during the winters when the Aberdeen was removed from service. The boat was later converted to tow logs for the Kelowna Saw Mill. When that was no longer viable, the Penticton was dismantled and abandoned on the beach near the mill. A few years later, the boat mysteriously burned to the waterline.

The feisty Captain Shorts, who became known as the “Admiral of the Okanagan,” wasn’t intimidated by the “grasping octopus of the CPR.” He bought another old hulk, named it Lucy, and took out an advertisement in the Vernon News to announce: “The opposition is here to stay, and so am I.” In spite of the bravado, Shorts couldn’t compete with the luxury, the schedule or the freight capacity of the newly launched Aberdeen. It wasn’t long before he left the Okanagan and headed off to strike it rich in the Klondike goldfields.

A New Era of Lake Travel

Sternwheelers have a long and storied history in British Columbia. Though often associated with the Mississippi River, the boats were used more extensively throughout this province than anywhere else in North America: they paddled up and down the stormy Pacific coastline, through rock-strewn rivers, and along the abundant lakes nestled between the mountain ranges. Some of these vessels were elegant and stately, finished with exotic teak and mahogany and outfitted with brass spittoons, ladies’ lounges and potted palms. Others were more like makeshift packing crates, built to carry men and supplies into the wild and otherwise inaccessible parts of the province.

Steam travel was slow in coming to the Okanagan. While paddlewheelers had been used on the Fraser River since the 1850s, most people coming to the valley either walked or rode, taking the original Okanagan Fur Brigade Trail along the west side of the lake, the Dewdney Trail from Hope and Father Pandosy’s trail down the east side of Okanagan Lake. The new boats, which arrived in the early 1890s, were flat-bottomed, made mostly of wood and had paddlewheels that only needed inches of water to generate enough thrust to propel them through shallow water or over river sandbars. On the lakes, the boats could nose up to a beach if no wharf was available—the paddlewheel would be left in deeper water, so it could reverse and get underway again.

Okanagan Landing, the terminus of the Shuswap & Okanagan Railway, was the location of a two-stall roundhouse, a freight warehouse and a hundred-foot-long wharf. At the time it was just a sleepy village with an old hotel, a general store, a red schoolhouse and a few summer shacks along the beach. Yet Okanagan Landing became the shipbuilding yard for the CPR: everything—the steel hull, the engines, the boilers and the fittings—arrived by train for assembly at the yard. The company’s master carpenters added the wooden decks while local sash and door factories supplied interior fittings. The Okanagan sternwheelers were launched sideways and since there was no dry dock, hull repairs required several teams of horses to haul the boats back up the stringers to be worked on.

The keel of the lake’s first paddlewheeler was laid in the fall of 1891 and the boat was launched on May 22, 1893. The SS Aberdeen was named after Lord Aberdeen, owner of the nearby Coldstream Ranch and Canada’s seventh Governor General. Given their experience with the colourful Captain Shorts and his boats, travellers were awestruck. The Aberdeen’s wooden keel was 146 feet long, and the paddlewheel added another 19 feet. The grand sternwheeler had two decks and a pilot house. As Captain Shorts had cared little for comfort, the furnishings of the Aberdeen were also remarkable. There was an observation lounge with plush seats and curtains on the windows, fine meals were served by stewards in a dining room fitted with fine silver and white linen, and passengers could request that the well-stocked bar be opened between ports. Though a trip down the lake rarely exceeded six hours, the Aberdeen had eleven comfortable staterooms for rent, each of which was fitted with screens to keep out the summer’s pesky mosquitoes. The CPR would advertise a package including rail travel from Vancouver to Okanagan Landing and travel aboard the SS Aberdeen to Penticton for thirty dollars per person.

The Shuswap & Okanagan Railway met the CPR mainline at Sicamous each Monday, Wednesday and Friday and delivered passengers and freight to Okanagan Landing by about 10:30. As soon as the people and cargo were transferred on board, the Aberdeen would depart and head south, zigzagging down the lake from the east side to the west side until it reached Penticton in the early evening. Since any settler could fly a white flag to signal the boat ashore, or light two fires on the beach at night, travel times varied. The Aberdeen returned north each Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, departing Penticton about noon, arriving in Kelowna about three and then travelling onward to Okanagan Landing in time to connect with the waiting train to Sicamous. The sound of the ship’s whistle would announce the Aberdeen’s imminent arrival, and though its time at each wharf was brief, everyone within hearing distance would gather to see who was coming and going, and to pick up the latest news—or gossip.

The Lequime Bros. & Company store across the street from the wharf soon developed a brisk lake trade: the boat would pick up orders from settlers along the lakeshore and deliver them to the general store or the butcher shop when they reached port. The filled orders would be picked up on the return trip, and dropped off at the respective homes.

Reliable and regularly scheduled boat service had a profound impact on the Okanagan as increasing numbers of settlers arrived in the valley to buy orchard-sized lots that had once been part of large cattle ranches. Advertising campaigns lured often innocent settlers to come, plant fruit trees and then enjoy the genteel lifestyle as they waited for their trees to bear fruit. New communities such as Peachland and Naramata came into being while others—including Kelowna, once thought to be too inaccessible to attract settlers—grew. People travelled with greater confidence and took comfort in the regular passenger and freight service. The Aberdeen could carry two hundred tons of freight and was sometimes so overloaded that crew had to walk along the outside rubbing boards to get around. The more established settlements flourished, as did the new communities that were springing up along the lakeshore.

1892: A Pivotal Year

As sometimes happens when a number of otherwise random events converge, 1892 became the year that the Mission Valley—and Kelowna, in particular—began to flourish. The Shuswap & Okanagan Railway, the SS Aberdeen, newly available land, ambitious British settlers and the Aberdeens: it was a unique combination. Newcomers were mostly young and energetic, well-educated and worldly, physically fit and looking for adventure. Several had money of their own or knew how to access it. Though Benvoulin was slated to become the valley’s premier townsite, its existence was still dependent on the much-rumoured new rail line.

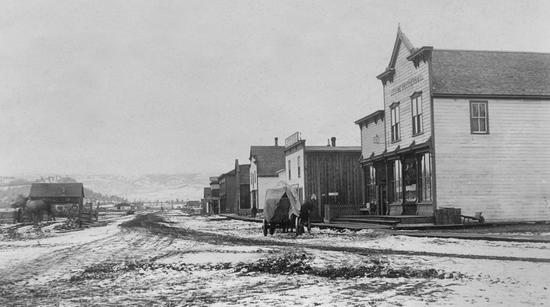

Bernard Lequime had created his own momentum: his sawmill was beside the wharf he had built at the end of the Kelowna townsite’s only street, to replace the original wharf farther along the bay. Then he named the street Bernard, after himself. Lequime’s general store was well established, and Archie McDonald had built the Lake View Hotel around the corner, next door. The hotel was the first in the new town and offered both travellers and those needing short-term room and board the additional benefits of a fine dining room and a well-stocked bar. With a veranda along the front of the building, a gallery along the second floor and twenty-five well-appointed rooms, McDonald’s hotel hosted many banquets, bachelor balls and receptions over the next few years. The backroom poker game was run by Tommy, the resident card shark, who was prepared to take on anyone, regardless of the time or the day. Later the same year, Messrs. Riley and Donald built a forty-by-sixty-foot farm equipment warehouse just east of Lequime’s store and then held a gala ball in the building before their stock arrived. A blacksmith shop opened and Thomas Spence ran the town’s first real estate business in the small cottage wedged in between Lequime’s store and McDonald’s hotel.

More settlers arrived and while some went into business, others bought land and planted orchards. Another general store was built and a few substantial three- and four-room family homes were built nearby. Single men built one-room shacks on the many empty lots around town, though in the summer they pitched tents amid the brush in what would shortly become City Park. Most of these men were unfamiliar with keeping a house or even cooking: many subsisted on bacon and eggs, learned to live with dust and used the lake for bathing, if they felt the need. It was, at least initially, a wonderfully unencumbered way to live.

With their Mission store as a prototype, the Lequimes’ Kelowna store soon became the trading and social centre for the new community. The outside stairway and second-floor room were available to any group in town who needed space to meet or celebrate. That space became the first schoolroom in Kelowna and supported what would become the remarkably vibrant social life of the frontier community. The first of an endless number of public concerts was held there on December 8, 1892, and featured Miss Thomson, who recited “Mary Queen of Scots”; Miss Blackburn and D.W. Crowely, who sang a duet; and Reverend Mr. Langill, who gave a recitation. Unnamed participants concluded the evening program with a reading of “The Society of the Declectable Les Miserables” before everyone joined in with rousing renditions of “The Maple Leaf Forever” and “God Save the Queen.” The settlers had to raise the funds for any service they wanted—a school, a church or a hospital, a band or a cricket club—and held concerts, balls and musical productions to entice people to contribute. These events soon became a regular feature of community life.

In fact, any excuse (or no excuse at all) seemed to give rise to an astounding array of social gatherings. Hard physical work and long distances rarely deterred residents from attending events in settlers’ homes or in the various hotels dotted around the countryside. A bachelors’ lunch at the Lake View Hotel might be followed that night by a dinner and dance at the Benvoulin Hotel; a cricket match would conclude with a banquet, a concert and then a ball. A thirty-mile trip by sleigh, wagon or horseback through a moonlit night to attend a gathering usually included the whole family, especially during the boredom of long winters. A frozen Okanagan Lake was no deterrent as horses and sleighs carried both people and freight across the icy surface.

There Was Always Time to Play

Many of those arriving in the Okanagan Valley at the time came out of the English public school system, where sports and the arts were ingrained parts of daily life, and they were determined not to change their ways. Cricket, long jump and foot races were on the same programs as horse races and lacrosse competitions. When the games were finished, competitors would turn their talents to the stage and mount expansive productions of most of what Gilbert and Sullivan had to offer. Celebrating Queen Victoria’s seventy-fifth birthday in 1894, local cricketers overwhelmed the Trout Creek (Summerland) team and then carried on to a splendid concert in the CPR warehouse. The building had been transformed with flags, bunting and evergreens and lit by as many lanterns as could be borrowed from around town. A large crowd from Vernon boarded the Aberdeen and travelled down the lake for the concert and then stayed on for the ball. There were undoubtedly many toasts to good Queen Victoria before they departed for home around three in the morning.

The next year, Vernon’s cricket team travelled to Kelowna on the steamer Fairview while a large group of merrymakers followed on the Aberdeen. The Kelowna team again proved to be invincible. The concert that followed featured songs by many local residents, a banjo solo by Mr. Dan Gallagher and a farce, Slasher and Dasher, where “the fun was fast and furious, and the audience convulsed with laughter.” A pattern was soon established: sometimes the visiting team would be from Vernon; other times, from Trout Creek. They might have been celebrating Dominion Day or raising money for the school, and the competition might start with baseball or lacrosse, then move on to the long jump, the high jump, the hundred-yard dash and a wheelbarrow race. Or it might involve a caber toss or the shot put, and finish up with a sack race. At other times, horse races would start the day. Before the town had a designated racetrack, Ellis Street, between Gaston and Bernard Avenues, served that purpose in spite of an abundance of mud, potholes and inevitable tumbles.

These sporting events would be followed by a banquet and a concert that might feature the black-faced Kelowna Minstrels or a farce where gentlemen played most of the roles, before everyone moved on to a ball. The Kelowna Brass Band was formed in 1894 and added their considerable talents to every community event. “The Maple Leaf Forever” preceded all goings-on while “God Save the Queen” concluded them. At a time when Kelowna’s population was less than one hundred, it was not uncommon for more than five hundred people to gather for these celebrations.

The season was irrelevant: Christmas offered many opportunities to gather, as did the many frozen ponds around the community. Married couples took on the singles in outdoor curling competitions, ice skaters donned masks “novel, beautiful and ludicrous,” and prizes were awarded to ladies for “fancy skating”… they were “the personification of fairy gracefulness.” Men also competed in fancy skating events and won prizes for being the best-dressed “gent masker”—where an otherwise ordinary man transformed himself into a Highland chief. In the summer, swimming, canoeing and sailing races were added to the list of organized activities and became the genesis of Kelowna’s legendary Regattas.

Other towns throughout the valley reciprocated with their own invitations. Shared social and sporting events strengthened the communities and enabled newcomers to replicate the lives they had left behind. As the bonds of community strengthened, friendships evolved into business relationships, and what might have been social or class barriers at home had no relevance in this new world. Kelowna was known from the beginning as having a spirit of friendliness between all sorts and conditions of people and a sense of social equality seemed to prevail. Vernon had the advantages of a railroad and government offices, while residents of Kelowna were forced to rally themselves to ensure their success. The early towns competed with each other over just about everything… and those early rivalries have never quite vanished.

A New Kind of Settler

Okanagan Mission had officially appeared on a map when its post office was established in 1872. However, as more newcomers congregated around the Kelowna townsite, it was discovered that three quarters of the mail delivered to the Mission was actually destined for Kelowna. The town finally got its own post office in 1893, tucked into a corner of the real estate office directly across from the CPR wharf—which was handy, since the company had the contract to deliver Canada’s mail.

The newcomers arriving in the Okanagan Valley in the 1890s had a different agenda to those who had come before them. The earliest settlers, with few exceptions, had struggled to survive in the remote countryside and had grown crops and kept livestock to feed their families and the few other people who travelled through the area. The next wave of settlers arrived with a more worldly view and tackled their new life with optimism. They intended to earn a good living and enjoy comfortable lives, and took the initiative to make sure that happened.

A substantial amount of small fruit was being produced by this time, along with a great variety of vegetables, hay and oats. It was more that the locals could consume, which led to the formation of the Agriculture & Trades Association of the Okanagan Mission: membership, fifty cents. The group lobbied the CPR for better freight rates and tried to guide members to plant crops that they knew they could find markets for. A succession of Kelowna Agricultural Fairs were held in the centre of town to showcase locally grown quinces, prunes, peaches, mangolds (a root vegetable used for feeding livestock), pumpkins, citrons, melons, onions and apples. Residents’ handiwork—including handmade shirts, embroidery, painting on silk, watercolours, some very fine oils, sketches and pencil drawings—was also featured, as was homemade bread, jam and cheese. It didn’t take long for the fall fair to outgrow the available space and land was bought for an exhibition hall. A half-mile horse racing track was nearby with space on its infield for lacrosse, football, and baseball.

Marketing the area’s produce remained a problem, though everyone was aware the Kootenay mines were flourishing. When about one hundred people lived in Kelowna, over five thousand lived in Sandon, in the Slocan Valley, where rich silver-bearing lead ore deposits attracted the optimistic and hopeful. Kelowna had its muddy main street, a couple of stores and a single hotel, but Sandon had twenty-nine hotels, twenty-eight saloons and one of the largest red light districts in the west. Of course, the young Kelowna was not planning to become that kind of a community, though the locals did consider the mines around Sandon as a potential marketplace. Alfred Postill and his friends saw the opportunity and formed the Kelowna Shippers’ Union (KSU) in 1893. At a meeting held in the Benvoulin Schoolhouse, $160 was collected to send a delegation of four plus a shipment of produce and hay to Sandon to see if it would sell.

The foursome left Okanagan Mission with their cargo, and travelled by boat to Okanagan Landing, caught the Shuswap & Okanagan Railway to Sicamous and the CPR to Revelstoke. Once there, their produce was loaded onto one of the Arrow Lakes sternwheelers, transferred over to Slocan Lake and carried on to Sandon. Though the CPR hadn’t yet completed its rail line into the community, the company had staked out a station and a freight shed. With the CPR siding on one side and the road to the mines on the other, the delegation traded their vegetables and hay for lumber, then dug a twenty-by-sixty-foot cellar, covered it and opened for business. Leaving Bob Hall, one of their delegation, in charge, the others returned home to organize more shipments of fruit, vegetables, hay and oats.

Before long, the KSU built a warehouse near the CPR wharf in Kelowna. Two years later, the original co-op disappeared and shares were sold in the new KSU, under new ownership. The names of the new shareholders would become synonymous with both the fruit industry and Kelowna’s development: Stirling, Hobson, Weddell, B. Lequime and Pridham.

The new organization flourished with an imposing building on the waterfront and a new wharf adjacent to the CPR wharf. Two years after its first foray into the Slocan, the KSU shipped seventeen railcars of vegetables and other farm produce. The venture was a greater success than expected, as orchardists realized their future depended on markets beyond the Mission Valley. They took the initiative and were soon sending wagonloads of apples and plums to Vernon, and later to the Prairies.

New opportunities spawned new products and services. A thriving hog business had developed in the Mission Valley but the unco-operative animals refused to be herded to market. A “pigaloo” was built just north of Lequime’s sawmill, with a slaughterhouse on the lakeshore, complete with a scalding trough and heavy tables for cleaning the hogs. The carcasses were taken to the smokehouse behind the KSU on Bernard Avenue, and instead of live pigs the resulting hams, bacon and lard were then shipped out of the valley.

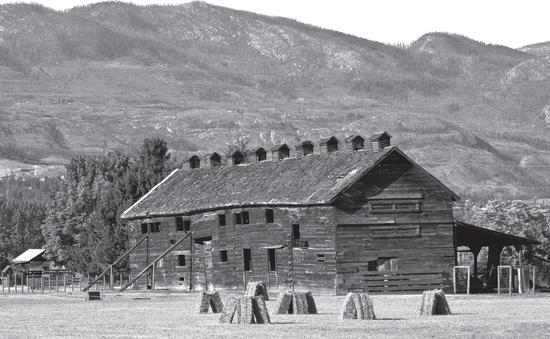

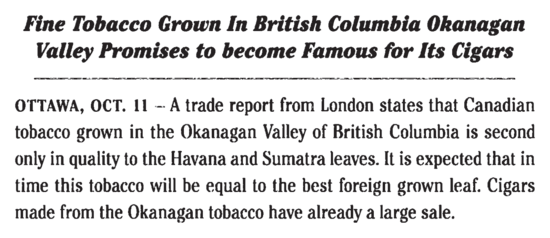

Louis Holman, a Wisconsin tobacco man, arrived in the Okanagan about 1893 and soon pronounced the valley’s soil most suitable for tobacco production. With capital from John Collins, newly arrived from England, the first crop was planted in the Mission across the road from the Lequimes’ blacksmith shop. The following year, C.S. Smith arrived from the West Indies and made some suggestions to further refine production. Several tobacco barns were built around the Mission, where the green leaves harvested in September were hung to dry until the usual January thaw, when the leaves were stripped off the stems.

The KSU added a cigar factory in a small building beside its packing operation where “Kelowna Pride,” its cut tobacco, was produced, along with hand-rolled cigars made of a blend of Havana and domestic tobacco. Attractive boxes of fifty were sent off to the miners in the Kootenay and Boundary areas, and for awhile it looked like tobacco would soon become the valley’s major crop. More acres were planted, more drying sheds were built, and when the Kelowna Shippers’ Union sent tobacco to the New Westminster Fall Fair in 1898 it won the second prize of one hundred dollars. With Okanagan tobacco making a name for itself beyond the valley, the future looked promising. As a news story in the Toronto World newspaper stated on October 12, 1914:

Kelowna Grows as a Town

Many of those arriving in Western Canada in these early years were transient, following the latest mining boom or a rumoured job. They stayed in one place long enough to make some money before moving on, often repeating this several times before finding a community to settle in. Some towns only lasted as long as the local vein of ore held out while others developed a reputation as being a pleasant place to live with an active, congenial lifestyle. Kelowna belonged in the latter category.

Kelowna saw significant development in the 1890s. The townsite, laid out in 1892, grew around the lakeshore and along Bernard Avenue, its main street. The Kelowna Saw Mill defined the industrial area immediately north of Bernard Avenue and because land to the south often flooded, residents built their homes, schools and churches eastward.

Dr. Benjamin De Furlong Boyce, the town’s first resident doctor, arrived from Fairview, the mining town near Oliver, in 1894. For many years he was the only doctor between Vernon and the US border, and on numerous occasions he and his wife, Molly, turned their home into a makeshift hospital. When contagious diseases such as diphtheria were diagnosed, patients were treated in the town’s new two-room jail. By this time, the temporary school above the Lequime Bros. & Company store had been replaced by a second school, a new one-room schoolhouse accommodating sixty pupils. D.W. Sutherland, who would eventually become both mayor and a local businessman, was sent by the provincial Department of Education to take charge.

Six-foot-wide wooden sidewalks were built along Bernard Avenue. Elsewhere, people had to make do with wooden planks laid end to end to avoid being mired in mud or blocked by massive puddles. Rain turned streets into quagmires and when Okanagan Lake flooded each spring, life almost came to a standstill. Sometimes the water was level with the wharves; the inundated sawmill would be forced to close, and rowboats replaced horses.

A few Chinese men settled near Mill Creek just south of the Lake View Hotel, and worked as cooks, lumber stackers and market gardeners. Kelowna’s Chinatown soon became significant, and on New Year’s Eve the street near the men’s shacks would be lit with thousands of firecrackers. The men worked hard and usually in mundane and relentless jobs that few others would do. Many still wore their hair in a queue (a braid) and were single, relying on each other to survive their hard lives. Arrests—for illegal mah-jong games and, reportedly, opium dens—were part of their daily lives.

Within a few years, however, the boom that propelled Kelowna’s early growth began to slow: by 1897, the area was hit by another economic downturn. The KSU was losing money on its meat-packing business and closed that down. Many orchards that had been planted five or so years earlier were bearing fruit, but sales were so slow that they couldn’t cover the costs of production. The promise of tobacco soon vanished as the mines closed and the valley’s best market disappeared with them. Efforts to revive the industry continued for several more years as various promoters tried to convince farmers to plant, but poor financial management, an inconsistent product and a challenging marketplace eventually caused the demise of Kelowna’s tobacco industry. New settlers continued to arrive but some of the old-timers had had enough and went looking for better opportunities elsewhere.

Bernard Lequime had been through slow times before and didn’t want to wait to see if things would pick up. He sold the Kelowna Saw Mill to his manager, David Lloyd-Jones, in 1901 and the still-empty lots he owned around town to Dr. Boyce. Lequime and his family then left for Grand Forks, sure that the Boundary country mines held more promise than the Mission Valley. Bernard hadn’t entirely given up on Kelowna, however, and kept his interest in Lequime Bros. & Company. The family’s original trading post in Okanagan Mission remained open until 1906, when the goods were transferred to the Kelowna store and the landmark business was closed. It wasn’t long before Archie McDonald sold the Lake View Hotel and left town as well.

By this time another Scot, Lieutenant Commander Thomas W. Stirling, RN, had arrived in Kelowna. “T.W.,” as he was soon known, had become a naval cadet at thirteen, served in Australia, India and South America, resigned his commission at the age of twenty-seven and travelled to British Columbia in 1894. He soon became one of the community’s leading citizens and was involved in just about every significant organization and event during the next ten years. Arriving with substantial working capital, T.W. bought land from the MacKay estate, built a large house and called it Bankhead, planted a pear orchard and imported purebred cattle and hogs. Stirling also bought shares in the Kelowna Saw Mill, became involved with the KSU and bought a large amount of empty land in downtown Kelowna.

By 1900, the KSU didn’t seem able to move beyond its Kootenay markets and since fewer people were employed in the mines and orchard production continued to increase, marketing became a problem... again. T.W. soon took the initiative and joined W.A. Pitcairn, an earlier manager of the Coldstream Ranch, to create Stirling and Pitcairn, to take over the crop marketing that had previously been done by the KSU. In 1901, they shipped their first boxes of apples to the Prairies: it took the Aberdeen about two weeks to collect the seven hundred boxes needed to fill a railcar from various orchardists around the lake. Stirling and Pitcairn shipped two railcar loads of apples to Glasgow, Scotland, two years later. One car carried apples that had been individually wrapped in a tissue-like paper; in the other car, apples had been directly packed into the boxes. It was an experiment to see which method delivered the best apples. The tissue-wrapped apples arrived in better shape and this became the standard method of shipping for many years.

Stirling was also at the forefront of the most significant change in the valley’s land use since G.G. MacKay had swept through the area. Real estate agents Edward M. Carruthers and W.R. Pooley joined with Stirling to buy Bernard Lequime’s 6,743 Mission Valley acres in March 1904. It cost them $65,000. In July of that same year, Stirling and Pooley formed the Kelowna Land and Orchard (KLO) Company and sold the land to the new company for $70,000. The following year, the original eighty-three-acre Eli Lequime homestead was added to the KLO holdings for an additional $12,000. The Kelowna Land and Orchard Company then built a bridge across Mill Creek, near Kelowna, and extended the road all the way to their new orchard lands on the East Kelowna benches. The area was being subdivided into lots ranging in size from one to forty acres, and a new ambitious irrigation system was installed. Untried orchardists flocked to the area. Everyone soon realized the best orchard sites were on the benches while hay, tobacco and onions were better crops for the valley floor.

Around the Town

Okanagan Mission

When the Kelowna and Benvoulin townsites were settled, newcomers began to move southward, beyond Father Pandosy’s Mission and across Mission Creek. Though a seventy-two-foot bridge had been built across the creek in 1879 and had made the trail to Penticton more accessible, it did little to encourage settlement. Giovanni Casorzo had crossed the creek and then gone uphill but others, initially undeterred by the lowland swamps, began to settle along the lakeshore and the hillsides above the lake. Crossing the swamps soon became impossible, however, and the settlers petitioned the government to build a road across the many marshes covering the area. Drainage ditches were dug, and a corduroy road with logs placed side by side was built. The logs soon sank and the road remained a sea of mud for most of the year. It was—and is still—called Swamp Road. A new Okanagan Mission school and post office were built beside the muddy road, and it wasn’t until 1912 that an alternative road was built to connect Kelowna with Okanagan Mission.

As the French abandoned the area around Father Pandosy’s Mission, the British moved in. Locations in the Mission still record the names of these early settlers who arrived around 1900 and created a vibrant community: Walker Road and Dorothea Walker School, Hobson Road and Crescent, Crawford Road and Falls, and Frost Road. A sense of permanence settled on the area when Gifford R. Thomson pre-empted land south of Mission Creek, near the lake. The family had arrived in the Mission Valley in 1892, purchased land from G.G. MacKay and built a house and planted an orchard, which didn’t survive the high water table and the cold winters. Undeterred, Thomson took on the mail contract and drove the stage from Benvoulin to Vernon on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, and returned on the intervening days, for which he was paid $600 a year. Thomson also planted hay and grain, ran cattle and eventually planted lettuce and celery. Today the property is a heritage farm and is still owned by the Thomson family.

Black Mountain and Rutland

Settlers from Missouri established a new settlement in 1893, at the foot of Black Mountain, about eight miles to the east of the Kelowna townsite. The families, most of whom were related, arrived in Penticton in their covered wagons and loaded their cattle, their wagons and themselves onto the deck of the Aberdeen and headed to Kelowna. They pre-empted land along Mission Creek and into the Joe Rich Valley, and by 1896 had built their own fourteen-by-eighteen-foot log schoolhouse and hired their own teacher. Eight families enrolled their children, some of whom travelled several miles to attend, and the kids and their families returned on Saturdays to clean the room and scrub the floors. The group built a larger school two years later and was by then well-established enough to have the teacher’s salary paid by the government. McClure and Prather Roads are named for two families of Black Mountain settlers.

A few years later, Australians John Matthew Rutland and his wife, Edith, were honeymooning in Canada and fell in love with the Okanagan. They went back home and sold everything they owned, then returned and bought the benches and flat land of what had previously been parts of the Brent, Simpson and Ellison ranches. John, called “Hope” by his wife (apparently because of his innate optimism), was familiar with horticulture and soon planted one hundred acres in apples. It wasn’t long before he had the area’s first substantial irrigation system underway, with several intakes along Mission Creek and a series of flumes and ditches snaking across his fields. Yet John Rutland was selling small parcels of his land to new settlers by 1904; it had been a demanding and expensive few years and the Rutlands had decided to move on. They sold the remainder of their holdings to the Okanagan Fruit and Lands Company, the same syndicate that had purchased much of A.B. Knox’s ranch a year earlier and was fast becoming one of the area’s major land developers. One of its principals was D.W. Sutherland, Kelowna’s first schoolteacher.

The Rutland townsite was laid out in early 1905. By that time, the Rutlands had auctioned off their livestock, farm implements and nearly new dining room, kitchen and bedroom furnishings and left Canada for Santa Rosa, California. The couple apparently made enough money from the sale of their land and possessions to ensure their independence for the rest of their lives.

Starvation Flats/Dry Valley

The valley running between Rutland and Knox Mountain was named Starvation Flats for a reason: it was used as a shortcut between Wood Lake and Kelowna and wasn’t good for much else. Riders passing through would be engulfed in a cloud of dust, as the earth had been left parched and barren by overgrazing. The flats had originally been settled by the optimistic and unknowing, and only dilapidated buildings and sagging fences were left to mark their forsaken dreams.

The name eventually evolved into Dry Valley, and it was clear that little would grow there until irrigation was available. The Morrisons, from Inverness-shire, Scotland, bought land on the west side of the valley and called it the Glenmore Ranch, after their family’s ancestral home. Once their house was built and the well dug, an irrigation ditch was carved out of the hillside. Water from small upland lakes flowed onto their land and irrigated the Central Okanagan’s first peach orchard. But for the most part Dry Valley remained dry for several more years, until developers arrived with money to finance irrigation schemes and advertising campaigns to attract buyers.

Kelowna as the Century Turned

Prospectors and dreamers on the way to the Klondike’s goldfields lifted the Okanagan Valley out of its early 1890s depression just as aggressive advertising campaigns enticed settlers to come and plant orchards. The land surrounding the Kelowna townsite was bought by a variety of development companies in a remarkably short period of time and subdivided, sold, irrigated and planted. Kelowna was not only a beautiful place to live but for relatively little money one could become an orchardist: life promised to be interesting and pleasant, and after the first year or so, easy. As a 1909 book on fruit ranching assured, orcharding “affords a satisfactory escape from the stress and strain of city life, and gives an added dignity and freedom to one’s sense of individuality.”

Stirling and Pitcairn were by now expanding their markets and shipping more and more apples out of the valley. Other enterprising newcomers arrived in Kelowna too, including F.R.E. (Frank) DeHart, who came to manage the Okanagan Fruit and Lands Company and then got involved in promoting the fruit industry. DeHart became one of the most successful fruit exhibitors in Canada as he introduced Okanagan fruit to surprised markets in Spokane, Washington, and then elsewhere in Canada, the US and Europe.

As more settlers arrived, so did the need for more classrooms and a large four-room school was built on the edge of town (it is now the Brigadier Angle Armoury). Several new battery-powered telephones connected homes to butcher shops, stables, the drugstore and the doctor’s office. Mr. Millie assembled several of these lines in his watch-repair shop, hired Miss Mamie McCurdy as the telephone operator, and then turned the system over to the newly formed Okanagan Telephone Company.

Crossing the lake became easier when the provincial government paid Mr. Lysons one thousand dollars a year to operate a twice-daily ferry service, weather permitting. The Skookum was a thirty-foot gas-powered boat with an eighteen-by-forty-foot scow attached to one side to accommodate horses, wagons or cattle. Passengers were charged twenty-five cents each while animals cost a dollar a head—most were likely left to swim across. The Bank of Montreal felt that Kelowna was ready for its own branch by 1904. Previously, residents needing the services of a bank travelled to Vernon, though most made do with wads of bills wrapped in binder twine.

A community newspaper was a status symbol back then, and signalled a certain maturity. R.H. Spedding had edited newspapers in small Manitoba towns and, while looking for a more benign climate, he discovered Kelowna was without its own newspaper. He published the first issue of the Kelowna Clarion on August 14, 1904. Week-old news arrived, already printed, from Winnipeg with the inside pages empty and ready to be filled with local news and advertising. The following year the paper was purchased by George Rose, who changed its name to the Kelowna Courier and Okanagan Orchardist.

Fire was a constant concern to newcomers whose time, money and futures lay in the shops, offices and homes clustered in Kelowna’s downtown. The sawmill’s frequent fires were often caught by the wind sweeping across the lake, endangering the wooden stores and houses nearby. Gas lamps also lit every home and shop, concert and ball, and bales of hay and straw were everywhere. Only so much could be done with buckets and manpower, and the town’s businessmen soon collected funds and bought the old Broderick fire engine from Vernon. The engine started its life in San Francisco in the 1850s and had been sold from one frontier town to the next until it ended up in Vernon. The old hand-pumped engine came with four hundred feet of hose at a cost of four hundred dollars, and arrived at the Kelowna wharf on the forward deck of the Aberdeen. It provided some protection… and some comfort.

By this time, Kelowna had grown dramatically. The south side of Bernard Avenue was lined with more-or-less substantial buildings that housed a variety of businesses: a bank, a newspaper, a drugstore, at least two general merchants, a furniture store, a post office, restaurants, two hotels and a CPR warehouse and billing office. The Anglican and Methodist churches were well established, as was the school. Two halls over the general stores remained available to the community or any fledgling organization wishing to raise money. The Kelowna Club, a private club for gentlemen, had been organized, and Masons congregated from other parts of the world and established St. George’s Lodge No. 41.

Kelowna, it seems, was never destined to become a wild frontier town. From the outset, those who arrived in the community were educated, worldly, and looking to replicate a familiar lifestyle. They were happy, however, to leave the social constraints of the old country behind. Opportunities were unlimited for those who wanted to make the effort, though a bit of working capital also came in handy.

In 1904, 299 qualified business and professional men petitioned the Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia for Kelowna to be incorporated. The charter was granted on May 5, 1905, and soon after Mayor H. Raymer, a contractor, was elected along with aldermen David Lloyd-Jones, owner of the Kelowna Saw Mill; E.R. Bailey, the postmaster; C.S. Smith, who had been the manager of the KSU for a number of years; and D.W. Sutherland, schoolteacher and land developer. Fifty-three years after Father Pandosy walked into the Mission Valley, about a thousand people lived in Kelowna and the surrounding area, and the townsite had eclipsed the pioneer settlements of Benvoulin and Okanagan Mission.