Afterword: Kelowna 2024

When The Kelowna Story was first published fifteen years ago, no one could have anticipated today’s Kelowna. The population has mushroomed, the skyline transformed, homelessness and mental health issues are everywhere, and national media outlets no longer need to explain where Kelowna is located. The city celebrates its national profile as one of “the best” places to raise a family, or retire to, or immerse yourself in the laid-back lifestyle, to live amidst beautiful orchards or world-class wineries, and ski some of the continent’s best powder at Big White. Sure, there’ve been a few “worst of” lists but not enough to stem the tide of people moving to town. With annual growth rates of between two and three percent, Kelowna’s 2010 population of 117,000 has ballooned to its current 160,500.

Urban planning in Kelowna has always been a curious mix of policy swings between building on the valley bottom and then on the forested hillsides, then back to the valley floor and then back to the hillsides. However, “densification” seems to be the buzzword of our time and it’s changing everything. Kelowna’s other reality—and part of its charm—is that fifty-five percent of its land mass is zoned agricultural, with forty percent of that locked in the Agricultural Land Reserve. And the situation is not likely to change significantly in the foreseeable future.

Most notably, the skyline is changing—and there’s even more to come, with an additional forty-eight towers in various stages of planning, including the forty-three-storey downtown campus for UBCO along with a forty-storey tower beside it. The Tolko sawmill site, which thrived for ninety years under various owners on forty acres of lakeshore on the northern edge of town, ceased operations in 2019. Although plans are still in the early stages, the site will likely be covered with additional towers and high-rises. What is presently two nodes of towers at either end of the downtown core will, in the foreseeable future, become a wall of glass and concrete.

A semi-permanent homeless tent camp along one of the city’s most popular recreation corridors is a shocking reality, and “temporary” tiny-home encampments are springing up in various parts of the community. As in so many other parts of the country, Kelowna has pressing drug addiction and homelessness issues, as high rental rates and stratospheric housing prices make income inequality one of our most visible problems. And then there are the climate disruptions that have already significantly impacted the valley.

Wildfires

These are not a recent phenomenon, as forest fires have always been part of Kelowna’s story, from its earliest days. In the 1950s, the RCMP descended on the town’s beer parlours, rounded up the guys enjoying a pint, loaded them into whatever vehicle was available and delivered them to fight the nearest forest fire. It was mandatory. There were no excuses. Local sawmills ceased operating, loaded their crews into pickups and big-boxed sawdust trucks, threw in all available shovels, pickaxes, pumps and hoses, and headed to the flaming hills. Often they’d be gone for days, and the town’s only supermarket opened at all hours to restock cookhouses to feed hungry crews. In about 1964, the now-legendary Martin Mars water bomber that served BC for over fifty years first pulled up to the beach at Bear Creek Delta, across from Kelowna, before going back out to refill the tanks on Okanagan Lake, and then head for nearby fires.

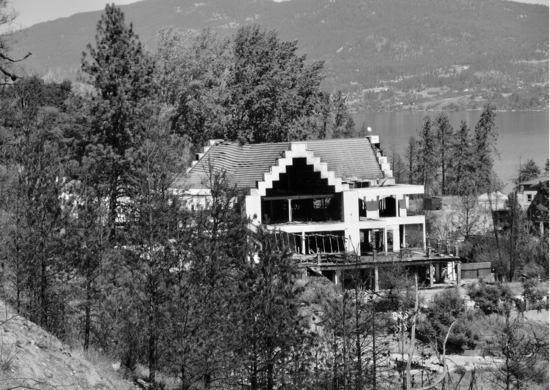

The Martin Mars was again on the scene in 2003 for the Okanagan Mountain Fire, and even today, many have called for it to be brought back to tackle our more recent blazes. The legend, however, has retired, and firefighting techniques have changed. No one expected the Okanagan Mountain Fire to burn its way to Kelowna’s suburbs, nor did anyone anticipate its fury. It did, however, transform how wildfires are understood and attacked. Now, a puff of smoke or open flame brings spotter planes overhead in minutes, with helicopters arriving shortly after, trailing water buckets filled with red fire retardant. This is now Kelowna’s summer reality. However, it isn’t just an Okanagan problem. We’re part of the global phenomenon of out-of-control, unpredictable, fiercely hot, wind-driven wildfires.

Kelowna’s prominence in national and international media also brings a certainty that those headlines will gravitate to the Okanagan when disasters happen. We’re a visual paradise. Our fir- and pine-covered hillsides fold into a spectacular lake, sailboats race across the sun-dappled bay, Sea-Doos zip around partiers hanging over the sides of pontoon boats and ocean-worthy powerboats cruise by. Each spring, rivers of wild arrowleaf balsamroot—the Okanagan’s own sunflower—cascade down mountain hillsides amidst layers of old pine needles and decaying vegetation. It’s a hiker’s paradise, but it’s also a wildfire paradise. As the planet heats up, so does the Okanagan. In the best of circumstances, the Okanagan is semi-arid, but after serial droughts, it is increasingly arid. Temperatures are rising, humidity levels are dropping and the population is growing—and, increasingly, choosing to live on the dry, tree-covered hillsides. There seems an inevitability to all of this.

West Kelowna’s McDougall Creek Fire in August of 2023, with flaming hillsides looming behind houses with their lights still on, made Time’s “Top 100 Photos” of that year. A succession of Okanagan fires has made for dramatic photos: night shots of brilliant orange and red flames racing along ridges and up mountainsides, and lakeshore homes engulfed as the camera lens caught the very instant the walls collapsed. RCMP patrol Okanagan Lake to keep the curious away from helicopters refilling their buckets before returning to the blaze. Orders to evacuate, appeals for safe refuge for animals, registration sites, school gyms and arenas as gathering places—it all kicks in, then anxiety levels peak and tourists are told to go home so locals can have the hotel rooms they’re occupying. And then the unimaginable: during the McDougall Creek Fire, embers from the west side of Okanagan Lake were caught in the fury of high-level winds, whipped eastward across two and a half kilometres of open water, and UBCO was evacuated. It seemed impossible. We’ve always assumed the lake was our best firebreak.

Our Orchards

Closed for the 2024Season: Unfortunately, due to circumstances beyond our control, we will not be opening this year as we have no produce or honey at all. Our sincerest apologies for any inconvenience this may cause. Thank you for your continued support. Looking forward to seeing you in 2025.

Dain Orchards sent this email to customers in the spring of 2024. Long my favourite peach grower, with their huge, juicy, luscious Redhaven and Glohaven varieties, Dain was signalling the 2024 tragedy of the Okanagan’s soft fruit orchardists. After weeks of speculation and waiting for the blossoms to open, they didn’t. And neither would they for nectarines, apricots, plums and some varieties of cherries—the stone fruits. December and January’s relatively benign temperatures had fooled Mother Nature into thinking spring was near, so the buds began to set in anticipation of warmth. Then on January 13, overnight temperatures fell to −25°C or −31°C, depending upon where you were in the valley, and killed them all.

Dain Orchards was tucked on the downside of Westside Road directly in the path of the previous summer’s McDougall Creek Fire. From the road, it looked like they’d been wiped out. Orchards and vineyards sometimes become firebreaks, however, as they are generally irrigated and ground debris is controlled. The Dains were surrounded by scorched pines and burnt undergrowth, but the orchard had been spared by the fire... and then it fell victim to winter’s cruel freeze.

There would be no Okanagan soft fruit to buy, sell, market or ship in 2024, and while it was not the only reason, this shortage factored into the demise of the eighty-eight-year-old BC T ree Fruits Cooperative (BCTFC) that had been the staple organizing body for orchardists since 1936. The tentacles of climate disruption are spreading. The Tolko sawmill site finally closed in 2019, after ninety years of producing various-sized wooden fruit boxes, plywood and dimension lumber. Several other nearby mills had already ceased operations, in part because of a fibre shortage from the years of beetle kill and wildfires, which had destroyed much of the marketable timber. Our valley’s historic industrial fabric is collapsing as climate disruption intensifies.

Crop insurance and government grants have helped, but the survival of the Okanagan’s signature orchard industry demands a long-term adaptation to an unpredictable future. A heat wave in June 2024 damaged early season cherries for the third year in a row, so orchardists are being impacted by climate issues at both ends of their growing season. Water should be a much bigger issue than it is: it’s the elephant in the room for both the agriculture industry and the city’s planning department. Our population continues to grow and both people and orchards ultimately draw their water from the same source: Okanagan Lake. Our collective memory of those early orchards and the abundant, enthusiastic irrigation schemes is just that: a memory. It’s a tough time for orchardists—their future is uncertain—and picturing the Okanagan without its orchards, which have been part of its defining story since the late 1800s, is heart-breaking. Perhaps the only plus of wildfire smoke is that it can prevent sunburn on some apple and cherry varieties as it acts as a sunscreen during intense summer sunshine. It also doesn’t seem to impact the flavour of the fruit, though it may impact the number of pickers willing to work in the smoke.

Smoke, however, poses a massive threat to BC’s wine industry, and “smoke taint” is becoming an increasingly problematic issue for many in the world’s wine-growing regions, several of which are also areas regularly impacted by wildfire. Smoke taint is the ashy, smoky odour produced from grapes exposed to smoke while they are ripening. The grapes absorb the compounds responsible for the smoky odour, though once inside the grape they cannot be smelled or tasted. It’s not until the yeasts used for fermentation are added that the smoky odour emerges. It’s a costly experiment.

After the 2003 fire, one of the wineries that escaped the blaze but not the smoke felt confident that their grapes would be fine. It was early days and little was known about smoke and grapes. There was much optimism that all would be well... until the wine was uncorked.

Our Vineyards

Tony Stewart, head of industry leader Quai ls’ Gate Winery, recently told a community group, “The wine industry is the canary in the coal mine for climate change.” If that is the case, it is entirely possible that the Okanagan may be on its way to becoming a laboratory that others in the world will turn to. We often think of climate change as coming sometime in the future without realizing we’re already living through it. The demise of the local mill and BC Tree Fruits, the loss of the stone fruit crops, and now the devastating impact of wildfires on the wine industry are all visible and visceral examples that should be impossible to ignore.

When the first edition of this book was published, there were about 200 wineries in the Okanagan. In the intervening years that number exploded, but it has recently shrunk to about 341 that continue to operate. As the industry tries to adapt in the midst of this latest crisis, that number could fall by fifty percent within the next few years. Some will consolidate, while others will vanish.

Most agriculture is temperature sensitive and thrives within specific ranges. In 2021, temperatures in Kelowna reached a high of 46.6°C. That winter, they dropped to −31°C: a temperature swing of more than 76°C in one year. That was also the year the town of Lytton disappeared in balls of flame and the year the White Rock Lake Fire destroyed approximately seventy homes at the northern end of Westside Road—the vital link along the western edge of Okanagan Lake and just twenty-five kilometres from where the McDougall Creek Fire would burn in 2023. The intervening winter recorded −30 for several days in a row, and then came the 2024 flash freeze. During the sustained extreme cold, after weeks of relatively mild temperatures, not only did the Dains and other orchardists lose their soft fruit crops but wineries up and down the valley lost their grapes and many of their vines as well. Wine is a premier draw for visitors to the Okanagan and the industry has worked tirelessly to establish and market their Vintners Quality Alliance (VQA) appellation. Beyond ensuring that these wines are one-hundred percent British Columbia grapes, they must also meet standards with respect to their origin, vintage and varietals. However, with the combination of lethal temperatures and wildfires, the VQA appellation may need to be put on hold while Okanagan wineries search for solutions, and perhaps find new varieties and root stocks that will thrive in the local terroir. California wineries have been dealing with similar issues and many are moving north to the more moderate climates of Washington and Oregon. Where would Okanagan wineries go?

And Then There’s Tourism

Summers have always belonged to Kelowna. From 1905 on, regattas drew settlers from all around the valley to participate in water sports and, inevitably, party. That’s pretty much today’s reality too. Though the regatta is no more, anything on the water is still essential—and the parties are still inevitable. Now, though, wineries, golf and farm gate experiences have been added to the visitor opportunities. June and September are busy but it’s July and August that need to be bustling, booked and full to capacity to ensure the tourism industry can survive for the rest of the year.

The string of summers dominated by smoky valleys and wildfires have grabbed the headlines, and tourists have become increasingly wary of the uncertainty as news spreads internationally as well as domestically. The 2023 McDougall Creek Fire grabbed headlines for several other reasons: airlines charging enormous fees to change reservations; Airbnb refu sing to refund customers whose bookings were in the fire zone; airports being closed to commercial flights; use of the lake restricted; and tourists already in town told to leave so evacuated locals could have a place to stay. Locals also became protective of their community and maybe weren’t at their welcoming best.

Though some may be drawn to the excitement of the fires, most are not, as smoke fills the air, the path of the flames is unpredictable, the destruction is profound and a prevailing sense of panic and fear permeates everything. Everyone is anxious and on alert, and fire-ravaged landscapes are never pretty.

In the summer of 2024, Kelowna had little smoke and no nearby fires—and yet the tourists stayed away. Uncertain, they made other plans. Tourism operators described the season as “underwhelming and frustrating.” Restaurants had empty tables, boat rentals were down fifty percent, golf courses had open tee times and job opportunities for young people have vanished. There may be other reasons visitors aren’t coming, such as the rising cost of living and changes in short-term rental policies, but most likely it’s an abundance of caution by those who don’t want to deal with the unpredictability of wildfires and smoke. The tourism industry will be increasingly challenged to find ways to market the Okanagan Valley, whose major charm and selling features have always been the sunshine, the brilliant blue skies, a beautiful sparkling lake and a laid-back lifestyle. That’s no longer a guarantee.

And Yet—and Yet

The magic remains! As I merge into heavy traffic at the top of Bridge Hill and round the bend, my breath catches. I know I want to live here. The vivid blue canopy of sunlit sky, the surrounding blue-tinged mountains and the glittering splendour of a very blue Okanagan Lake always astound me. I watch the sun catch the wake of powerboats weaving along the sides of the W.R. Bennet t Bridge and then reflect off white sails in the distance. A happy-face parachute dangling a thrill-seeking but terrified passenger floats by. There’s a canopy of green over much of the city and tall trees line the beaches in City Park as sun worshippers bake on the strip of golden sand by the lake. And, in spite of the growing number of high-rise towers, Kelowna remains the most beautiful city anywhere. That sense of magic and promise from earlier times still holds, and I’m reassured that Kelowna will survive the chaos of growing so quickly, and will become an even better version of itself as it settles into its unknown future.

Sharron J. Simpson Kelowna, BC October 2024