Chapter Three: Kelowna Flourishes, 1905–1930

The first few decades of the twentieth century were golden years in the Okanagan. Vernon was the valley’s leading city and the location of most government offices, including the recently completed and imposing red granite court house. A charter had just been granted for the Midway & Vernon Railway (M&V) to connect the mines in Greenwood and Rock Creek, through Vernon and along the Shuswap & Okanagan Railway, to the Pacific ports. Raising money to pay for the line was challenging, but just as a provincial subsidy was about to expire in the last days of 1903 a small survey crew climbed the hillsides south of Vernon and marked the proposed rail line along the west side of Kalamalka Lake.

Price Ellison, by this time the area’s influential MLA, fired a blast of black powder off the rock face above the lake to launch the project and then headed to the Kalamalka Hotel for a gala dinner. Ongoing funding for what became known as the “Makeshift & Visionary” railway never materialized, however. The quarter mile of roadbed carved into the hillside above the lake’s azure surface is all that remains of a pipe dream.

The excitement about the M&V was a momentary diversion from the real railway news at the south end of Okanagan Lake. Wagon trains were still supplying the mining areas east of Penticton as surveys were being completed for the Kettle Valley Railway (KVR). Both Canada and the CPR needed the ore and the territory of the Southern Interior to remain Canadian and saw this rail line as the best chance of ensuring that happened. Completed in 1915, the KVR was both an engineering marvel and one of the costliest railroads ever built anywhere. It ran from Hope to Midway, connecting the mines of the Kootenays to the coast. Penticton was the railway’s Okanagan headquarters and when the first engine pulled into Lakeshore Station in May of 1915, both the city and the South Okanagan were energized.

Though Kelowna had been promised its own rail connection by many politicians, over many years, nothing had materialized. Its residents were left to watch and wonder as the KVR’s great steam locomotives were barged past their town on the way to Penticton. Though the rail line between Beaverdell and Penticton came tantalizingly close to the East Kelowna benches and stagecoaches delivered some passengers to the Myra station, this was not Kelowna’s railway.

Yet newcomers still managed to find their way to the Central Okanagan. Many succumbed to the advertising campaigns extolling the valley’s climate and the lifestyle opportunities inherent in orcharding. Some packed up their families and their belongings and moved here while others working their way across the country heard rumours of the area, came to have a look at Kelowna and chose to stay.

James B. Knowles left Windsor, Nova Scotia, in about 1905, after his family was decimated by illness and fire. He travelled by train to Vancouver and apprenticed with Birks Jewellers before scouting around for the best place to set up his own business. Jim wrote his fiancée, Lou, who was still in Nova Scotia, and told her about three possible locations, adding that Kelowna was on a lake. That was all Lou needed to know and it wasn’t long before she climbed on the transcontinental train and crossed the country to Revelstoke. Jim was waiting, and they married before continuing on to Kelowna, where they were met by well-wishers who showered them with rice as they walked down the Aberdeen’s gangplank. The local paper reported that the Chinese men standing nearby thought it was a very strange way to waste perfectly good food.

The couple built a house on Bernard Avenue, at the edge of town just beyond the Presbyterian Church. Jim became the first jeweller in the area, helped organize the new Kelowna Regatta, served on the town council and became one of the first advocates for preserving the community’s history. Lou was ahead of her time and spent many years working in the store alongside her husband.

Most of Kelowna’s lakeshore near town flooded each spring and the water table was so high that other parts were covered with swamps, bulrushes and mosquitoes year-round: it wasn’t the town’s most sought-after real estate. A few of the hardier newcomers still wanted to live and play near the lake in spite of the conditions and sought out the higher parts of the shoreline. Cottages were built, each with its requisite screened-in porch. Camp Road, at the north end of town, was one of the first areas to attract summer residents, including Jim and Lou. They paid fifty dollars for their lot and lived in a tent until they could afford to build their camp. Lou thought “Camp Road” was much too common a name for their neighbourhood, though, and talked her fellow cottagers and the town council into upgrading the area’s image. It was soon known as Manhattan Drive.

Those wanting to travel beyond downtown had to be prepared for the challenges: Jim and Lou Knowles and their neighbours put their boats in the water at the foot of Bernard Avenue and rowed north along the shoreline to reach their campsites. When the land dried out, a narrow trail was cut through the bulrushes and residents could walk or ride their bicycles. The trail was soon widened for cars but Brandt’s Creek remained an obstacle until two large logs were laid across the channel. It helped if a second person stood nearby and shouted out directions to the driver.

The new town council enacted various bylaws and the lantern of the “honey wagon” could be seen swaying in the early morning as the horse-drawn wagon passed up and down the back lanes to empty galvanized privy buckets. Yet it was many years before the last of the outhouses disappeared, in spite of the high water table. The lines between country living and city life were none too clear at this time, and when cowboys crossed the new town’s boundaries, their “furious riding” and lack of inhibitions about firing their guns sorely tried the patience of the city fathers.

Dr. Boyce had lived in Kelowna since 1894 and felt he needed to upgrade his skills. Not wanting to abandon his patients, he began looking about for someone to take over for the six months he would be in Montreal. Dr. W.J. (Billy) Knox (not related to the pioneer rancher, A.B. Knox) had just finished his medical training at Queen’s University. Without the funds needed to intern or specialize, he had booked onto the SS Empress of China as the ship’s doctor. While waiting in Vancouver for the ship’s arrival, Knox heard about the short-term position in Kelowna, including the monthly salary of seventy-five dollars, and barely hesitated before accepting the job. When Boyce returned, Knox headed back to Vancouver to join the ship on its next sailing. Fate seemed to intervene again when there was another delay and Billy, impatient to get on with his life, decided to forgo the adventure and returned to Kelowna. He joined Dr. Boyce’s practice for a few months before branching out on his own.

Seeming to thrive on the challenges of frontier medicine, Dr. Knox travelled the valley in a cutter or sleigh, by horseback or by boat. His black medical bag was filled with the likes of mustard for the mustard plasters used to treat chest congestion, or laudanum (a mixture of alcohol and opium) to quieten a cough or a fretful child. Knox became a beloved and legendary presence in the community: he delivered over five thousand babies, looked after several generations of the same families and never forgot a name. During the sixty years he practised medicine, Dr. Knox became the embodiment of the healing power of devoted and loving care. Prime Minister Mackenzie King couldn’t entice him into his cabinet, though he was subsequently awarded the Order of the British Empire (OBE) and an honorary LL.D. from Queen’s University. Billy Knox passed away just before his ninetieth birthday; the Dr. Knox Middle School is named in his memory.

Citizens began lobbying for a local hospital soon after Kelowna was incorporated. A society was formed and set about raising the necessary five thousand dollars while the Ladies’ Aid and Young Ladies’ Aid promised to provide the linens and keep them in a good state of repair. The Kelowna Land and Orchard Company and T.W. Stirling donated twelve acres to the Hospital Society. The land was on a bit of a rise, running from Pendozi Street to the lake. Access to the new hospital was off Pendozi Street, down a winding dirt road cut through the brush and aspens. Sometimes a canoe could be paddled up to the building from the north when the spring floods inundated the lowlands between the hospital and town. (Today’s much expanded Kelowna General Hospital occupies the same site minus Strathcona Park, which was gifted to the city in 1950.)

This was quite an achievement for a community of just over six hundred people, in the townsite proper. When Price Ellison, MLA, was called on to officiate at the opening in April 1908, he arrive late and then complained that he really didn’t know why Kelowna needed its own hospital. Was it not entirely feasible for residents of this town and the Mission Valley to go to Vernon if they needed hospitalization? Ellison lived in Vernon and had been badgered by Kelowna Conservatives to share the provincial funds allocated for the Vernon hospital, and he wasn’t happy about it. He then concluded his remarks by referring to the good-looking nurses (much to their embarrassment) and added his hopes that the Kelowna hospital would never be full.

The town ignored him and rejoiced in its accomplishment. The building’s lower floor was made of cement blocks and left unfinished while the wood-clad upper floor was painted green to blend in with the natural setting. The roof was red and could easily be seen from a distance. The roughed-in basement housed the kitchen, the dining room, the nurses’ quarters and the heating system. The upper floor housed two six-bed wards—one for men and the other for women. Two semi-private and three private rooms were also available for those who could afford to pay: daily rates were set at $1.50 in the wards, $2.00 for a semi-private room and $2.50 for a private room. Full linen and silver service was also available in the private rooms. Four bathrooms were roughed in but funds were only available to finish two. Large windows in the operating room ensured maximum light and most of the equipment was supplied by Mr. Stirling, while Dr. Boyce paid for the heating system. A septic tank had been installed to deal with the building’s sanitation needs but it didn’t take long for the system to be destroyed by the disinfectants being used in the hospital. Bedpans then had to be taken out back and emptied into the bush, and the sites covered with liberal doses of lime to kill the germs.

When they began taking up a disproportionate number of beds, pregnant women were told to have their babies at home. A ten-bed maternity wing became the hospital’s first addition and was quietly opened in 1914, a month after World War I was declared. Sometimes it seemed like Ellison’s opinion that Kelowna didn’t really need its own hospital might be true: paying the bills and keeping the doors open was often a challenge. Hospital Society directors pleaded with citizens to help in any way they could: a call for food for the patients resulted in the arrival of fruit salad and lemonade, canned peaches, sacks of potatoes, loaves of bread, grape juice, pickles, chickens and wild game. Other times the hospital asked for firewood and coal but gratefully accepted whatever was dropped off. The nursing staff (two), the cook and the caretaker cheerfully agreed to cuts in pay so the hospital could keep running, while local merchants were asked to extend their credit terms. With rigorous management, the hospital’s directors reduced their 1916 deficit to $32.32.

Elsewhere, Kelowna was taking on the appearance of a more substantial community. Elegant houses were appearing along Bernard Avenue, where circular driveways met columned porches and gracious gardens. The Stirling family moved to town from their Bankhead orchard and built Cadder House near the hospital. It has gone through many incarnations since 1911 but is one of the few early houses still in existence. The hospital included accommodation for nurses but when those rooms were needed for patients, Cadder House served as the nurses’ residence. When it became too difficult to work around and over patients during a renovation, they were moved, many on stretchers, to Cadder House until the construction was finished. The house was subsequently converted into a group home until being rescued in 2004, when it was restored and made into condos.

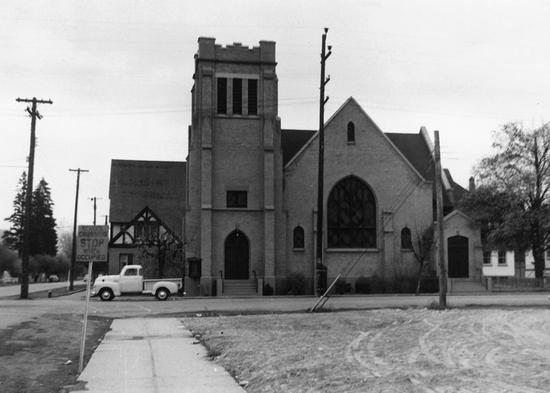

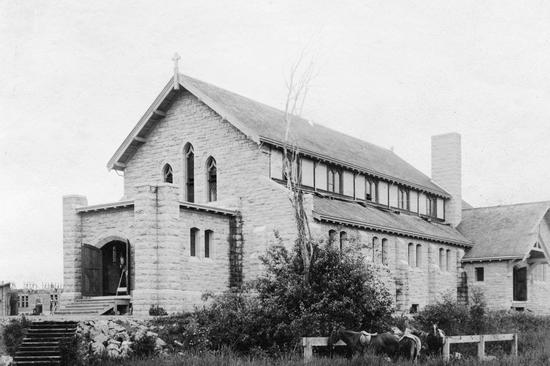

Presbyterians, not wanting to have to travel to Benvoulin to attend church, built their first Kelowna church in 1898 and named it after A.B. Knox, who had donated the land upon his return from jail. The original building was replaced by the current red brick building in 1909. With the amalgamation of the Congregationalists, Methodists and some of the Presbyterians, this became the First United Church. The Anglicans had established their own church in the town centre in 1894, but when their congregation grew they were torn between adding on to the original building or beginning again. The decision was made to move to higher ground and farther out of town. The cornerstone for a new St. Michael and All Angels Anglican Church was laid in 1911, southeast of the main townsite. Built of local stone and trimmed with granite from a quarry near Okanagan Landing, the “ecclesiastical Gothic” design took two years to complete.

Many of the original settlers and their descendants, the parishioners of Father Pandosy’s Church of Mary Immaculate, had moved or died by 1902, when the Mission church closed its doors. It has been a church for forty-four years and while the property was sold, the original buildings were left on site. The Catholic community was so small by this time that priests came from Vernon for services for the next few years. By 1908, the congregation had replenished itself and needed its own priest. Land was purchased in Kelowna, cleared of brush and pine trees, and the new Church of the Immaculate Conception opened three years later. This was the third Catholic building in the Central Okanagan, though only the second church, as Father Pandosy’s original Mission building was a chapel. The bell that Rosa Casorzo had followed from San Francisco was hung in the new bell tower and statues donated by the Lequime family were moved to the new church. All were subsequently moved again to the third and present Immaculate Conception Church in 1962.

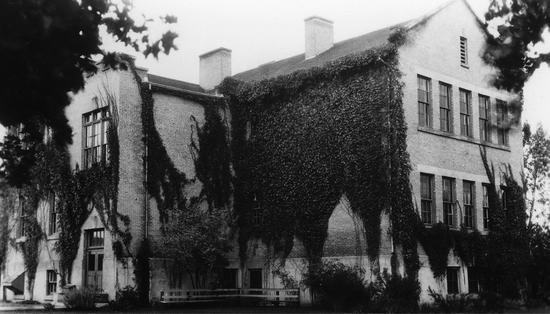

Kelowna quickly outgrew its one-room schoolhouse, just as it had the little tables and benches of the school above Lequime’s store. A wood-frame four-room Board School was built in 1903, just behind the Knox Church. Irrigation ditches flowed along two sides of the building. It subsequently became the School of Manual Training and Domestic Science, before being transformed into today’s Brigadier Angle Armoury. Students wanting to continue their studies beyond elementary school initially went to Vernon or Grand Forks. Kelowna’s first high school was built across the street from the Board School in 1909, though senior students had no sooner moved in when they were forced out to make room for the ever-increasing number of younger students. Senior students were subsequently relegated to vacant rooms above the downtown stores until the 1913 completion of the new Kelowna Public School.

Now known as Central School, this imposing, classically designed ten-room red brick building could not be officially opened until the Honourable Mr. Ellison came to town. Featuring the latest designs, each room had no less than 280 square feet of windows with desks arranged so light would fall from the back and left hand of each student—at the time, left-handed students were “encouraged” to write with their right hand. The cloakroom attached to each classroom contained a “sanitary bubbling drinking fountain in which no cup is used, nor do the lips come in contact with anything but the stream of water which bubbles up at the drinker’s touch.” Teachers entered through the side doors while students lined up on either side of the huge woodpile in the playground at the back, and entered through the rear doors. At a recent reunion these same students were invited to enter the school through the main Richter Street doors. They were aghast—none had ever entered the school that way before, and most didn’t recall ever seeing anyone use the front doors. Kelowna’s citizens placed a high value on education and as the town continued to grow, bylaws were passed that added the cost of building more schools onto their taxes. During the 1920s, a four-room primary school was added behind the Kelowna Public School and the red brick Kelowna Junior High School, one of the first in Canada, was built on the other side of Richter Street.

Downtown also began to change as permanent-looking buildings replaced the clapboard stores lining Bernard Avenue. Lequime Bros. & Company moved across the lane into a stone building with large plate-glass windows to better display their merchandise. The Royal Bank and the Canadian Bank of Commerce soon joined the Bank of Montreal and built substantial and appropriately imposing buildings along the north side of Bernard Avenue. They were within a block of each other. The grandly named Kelowna Opera House opened—it was really the upper floor of the Raymer Building where the Raymer family lived. The Masons and Oddfellows had their respective halls in the same building, with the Thomas Lawson General Store and the Mason and Risch piano showroom on the ground floor.

The Kelowna Opera House was the centre of the community’s social life and with its fine stage and sloping floor, it offered an array of entertainment. Amateur productions of The Mikado and The Pirates of Penzance were among the Gilbert and Sullivan favourites, with costumes and sets designed by people who had worked in the best British theatres. Hortense Nielson, “America’s greatest emotional actress,” toured with Norval MacGregor, the world-renowned Shakespearean actor. High-brow culture was interspersed with the more common; this was a time of travelling wrestlers and moving pictures with titles like as How Rastus Got His Pork Chop (tickets were fifteen or twenty-five cents).

An early morning fire was discovered in the rear of the opera house on October 31, 1916: it “obtained a great hold on all the rear and upper part of the building” before being discovered. Roaring flames were fanned by strong winds and it took the fire department over five hours to contain the blaze. By that time, only a few brick walls were left standing and the loss was over $135,000—only some of which was covered by insurance. Kelowna’s only opera house vanished into history.

City Park: A Visionary Buy

High water levels and frequent flooding were such a problem in the new town that the adjacent forty-one acres of bush and pine were never included in the original townsite plan. The lakeshore was a lovely place to be once the floods receded, and the town’s bachelors would quickly pitch their tents along the beach for the summer. Bernard Lequime’s original wharf and warehouse were abandoned when a new wharf was built at the foot of Bernard Avenue and the campers had all the amenities they needed. A diving board was added onto the end of the old wharf and a wall was built along the east side to ensure their privacy—no women and no bathing costumes!

Before he left town, Archie McDonald, the owner of the Lake View Hotel, had built a bandstand across from his hotel and cleared enough bush to create a playing field, but they were also only accessible and usable when the floods subsided. The locals were annoyed with the high water and in 1908 complained to the government in Victoria about the inconvenience. Public Works in Penticton was ordered to clear debris from the mouth of the Okanagan River and along the connecting channel to Dog Lake (Skaha Lake). The cleanup was so successful that lake levels dropped dramatically and the wharves around the shoreline became higher and drier and then totally inaccessible. When a control dam was built at the mouth of the river in 1914, it was assumed the problem was solved. It was… for awhile.

In spite of the recurring floods, the community saw the potential for a sizeable park adjacent to downtown. A referendum was held in 1909, and citizens voted—146 to 43—in favour of paying David Lloyd-Jones $29,000 for the thirty-six acres. By 1913, the town was abuzz with a proposal to build a fine hotel in the new park. Attractive drawings were shown around and the Board of Trade made presentations to city council, stressing the value of this fine modern hotel and urging their support for the initiative. A plebiscite asking citizens if they supported the hotel proposal was held later that year. Most were furious at the thought and didn’t support the proposal. The question of hotels, development and parkland would arise again, and again, in Kelowna. An orphaned five-acre parcel near the park entrance belonged to Bernard’s niece, Dorothy Lequime, and it was another ten years before Kelowna and Dorothy, who still lived in San Francisco, agreed on a price for the remaining land.

Orchards Flourish

These were great years for the real estate business. Where no orchards existed, agents nurtured a dream. The cachet of the Aberdeens continued to entice Brits and Scots to the valley while others came because of the lifestyle. Bernard Avenue was extended beyond the Knox Church to the top of the ridge and new residential areas grew up along Richter Street. The townsite grew southward along Pendozi Street and past the new hospital. Yet it was several more years before the low-lying land to the south of town, adjacent to Okanagan Lake, could be settled.

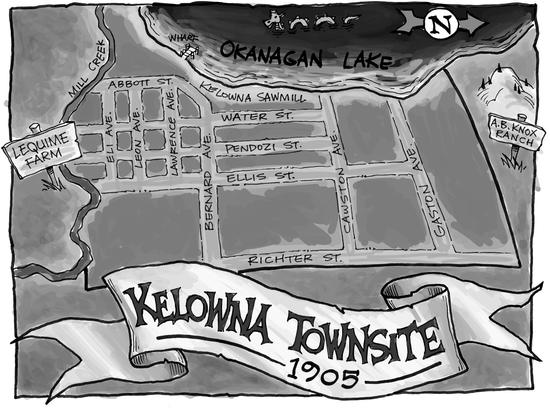

When the map of the new Kelowna townsite was deposited at the Land Registry Office in 1892, the street named after Father Pandosy appeared on the map as Pendozi. Though most of Kelowna was aware of the error, no one corrected it and the name was left misspelled for many years. In 1939, the new provincial government ferry was named the MV Pendozi though everyone knew it wasn’t correct. One hundred years after the good priest arrived in the Okanagan Valley, the historical glitch was corrected and his street was finally renamed Pandosy Street.

Orchard development continued beyond the townsite: the Bankhead orchard’s pear trees covered the area east of the city boundary, including a line of fast-growing Lombardy poplars that had been planted as a windbreak. Orchards appeared on the KLO benches while the South Kelowna Land and Orchard Company, farther to the south, declared the Bellevue Hotel—the original Thomson homesite—the centre of the Okanagan Mission townsite. Its four thousand flat acres were planted in tobacco, hay and orchards. East of the Rutland orchards, Belgo-Canadian Land Company, funded with Belgian capital, planted six thousand acres, imported workers from Italy, and built a fourteen-mile irrigation ditch from the north fork of Mission Creek. The Central Okanagan Land Company paid $100,000 for 1,665 acres of rangeland, on the northeast boundary of the Rutland orchards. This was the northern gateway to Starvation Flats, or Dry Valley, and it didn’t take long for the company to option another six thousand acres and begin an impressive cross-Canada campaign to sell the properties.

Marketing the agricultural possibilities of Dry Valley seemed a bit of an oxymoron so the company ran a contest to rename the area: the winner would receive one hundred dollars. Various suggestions were offered, including “Hardpan Hollow” and “Alkali Akres,” but “Glenmore,” with its Scottish meaning of “beautiful valley,” was more to the company’s liking. Two submissions suggested the same name and the winners shared the prize money. Private railway cars brought prospective buyers from Eastern Canada. Most were city dwellers with little or no experience on the land, with orchards or even with farming. Many had selected their lots from maps and signed purchase agreements before leaving home, and several weren’t happy with what they found upon their arrival. Lot sizes ranged from ten to sixteen acres and pricing was based on the distance from Kelowna: four hundred dollars an acre half a mile from town; three hundred if three miles; and two hundred and fifty for three and a half miles and more. The company’s assurances that “Glenmore will be settled by a very superior class of people” had a decided allure. Some purchasers never lived on the land and hired the company to clear it and plant and harvest their crop. Others found managers to do the work for them. The company had engaged Dominion Trust Company of Vancouver to finance their development and irrigation system by issuing $500,000 in bonds. By 1914, $100,000 of the debt had been retired but when Dominion Trust collapsed later that year, the Central Okanagan Land Company was forced into liquidation.

Not all promoters were honourable and for a time, the valley seemed overrun with real estate agents. A 1912 Royal Commission lamented that many individuals had suffered much injury and the province’s reputation had worsened at the hands of those who misrepresented the conditions and earning potential of the orchards. Even reputable companies were inclined to embellish the benefits and prestige conferred on owners of Okanagan land.

Water—Always an Issue

Water became crucially important as the Okanagan Valley moved beyond cattle ranching to more intensive agriculture. Early settlers established themselves close to creeks and built simple dams to divert the flow of water into furrows cut between rows of trees. Other times, heavy spring runoff flooded large acreages and the resulting soak would suffice for the season. Disputes were inevitable: water would seep through dirt trenches and flood neighbouring fields; upstream users diverted creeks and downstream users didn’t get the water they felt they were entitled to. The district engineer and the water bailiff mediated but if they couldn’t reach an agreement, lawyers were hired and a judge was left to decide. Other times, frontier justice ruled as with the lady in Okanagan Mission who sat on the control gate of the irrigation channel with shotgun in hand and resolved things her own way.

Water from Mill Creek ran in open ditches up and down residential streets for many years. Several ponds were scattered through Bankhead and served as reservoirs and swimming holes in the summer and skating rinks and sources of ice in the winter. (Most of these ponds have since been filled in.) Development companies quickly understood their success was dependent on the availability of water. Irrigation was such a substantial part of initial development costs that the early systems were small, often makeshift and sometimes barely adequate. The intent was to use the income received from selling the lots to improve and then expand the irrigation systems. Engineering expertise was sometimes available and sometimes in sync with local conditions, though often not. When flumes and pipes were used for short periods of time they rusted and split while the alternating freezing and thawing of the Okanagan winter destroyed even the most simple of systems. Cattle wandered through or over furrows and ditches, weeds grew in and around, gophers dug their own diversions and inexperienced construction crews were just glad to have a job and weren’t driven to excellence.

Most irrigation companies were subsidiaries of the privately owned development companies. As the economy slowed in 1913 and the Great War followed, settlers, and the growth they brought with them, vanished. Few companies could deliver on their promises of irrigation and several were forced to liquidate. The prospect of Okanagan orchards and no irrigation was so alarming that the provincial government stepped in with loans so systems could at least be maintained. Planning was short term and there was little collective effort to deal with the ongoing and growing demands for water. The government loans had to be forgiven by the 1920s, when irrigations districts were created with a mandate to ensure that all orchards would have access to water for irrigation.

Of Packinghouses and Canneries

As the number of orchards grew, the foundation was laid for what has become the recurring marketing dilemma of the industry. Some growers built their own packinghouses, found their own markets and remained independent. Others joined co-operative associations and pooled their packing and marketing functions. Small-scale co-op marketing had been going on for some years but serious competition from growers outside the valley led to the creation of the Kelowna Growers Exchange in 1913. By the time the war ended, markets had changed again and the majority of valley growers joined the exchange. Increasing amounts of small fruits and vegetables, grown between the rows of apple and pear trees, were also presenting marketing problems. Some were shipped to the Kootenays and subsequently to the Kettle Valley construction camps, but there was much more produce available.

Fraser Brothers built the Kelowna Canning Company in 1910, across from City Park. It was the first business in what would become a thriving Okanagan industry. Pumpkins, beans and tomatoes were canned before the company branched into soft fruits. When much of the building was destroyed by fire a few years later, the plant moved north of Bernard Avenue and changed its name to Western Canners Ltd. A wood-frame building was built over the swamp and bulrushes, and Chinese workers peeled the tomatoes by hand and were paid on a piecework basis. Cans were shipped to Kelowna from Vancouver in the same two-, three-, and ten-gallon sizes that had been used by the coastal fish canneries. Once the cans arrived in the cannery, they were filled, wrapped with “Okanagan Brand” and “Standard of the Empire” labels and shipped out of the valley. Soon the wooden building was replaced by a more substantial brick structure and a room was added to make sodas. The company began selling on the Prairies, but as the economy turned down and the bank refused further financing, they closed their doors.

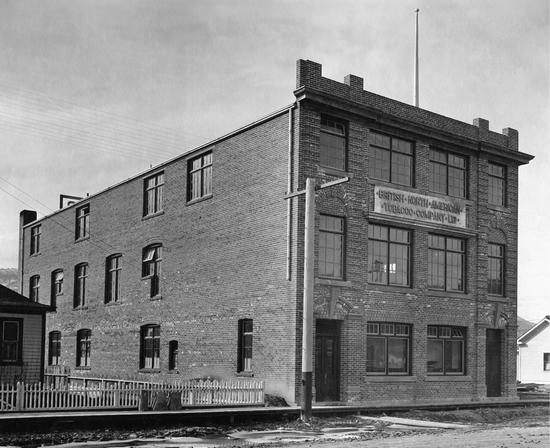

By then, the Occidental Canning Company had already set up business in the old brick British North America Tobacco Company building with machinery from another bankrupt canner. Since seasonal workers were hard to find in town, men were hired in Vancouver, put up at the Occidental bunkhouse and fed in the company’s communal kitchen. The bunkhouse was sold when local workers became available: European immigrants who settled in the Okanagan after the war, and the women who filled in during the war and stayed on the job. Most workers were “on call” yet few had telephones, so they arrived at the cannery door each day, hoping to get hired for one of the shifts.

Tomatoes were a huge part of the cannery’s business. Horse-drawn wagons loaded with tomatoes lined up along Ellis Street and around the corner onto Bernard Avenue. The smell of processing tomatoes and spicy ketchup wafted over the whole community. Men loaded cans onto dollies and moved them from one work area to another while the women sorted, cut, peeled or pared tomatoes and packed them into cans. The best tomatoes were canned whole while those that were soft or bruised were diverted to the juice line. Those just a step or two away from being thrown out were made into ketchup, and it was a demanding job. Large vats wrapped with copper coils were lined up along the outside deck at the rear of the cannery. As quantities of sugar and spices were added, the risk of burning was so great that once started, the stirring couldn’t stop until the batch was finished. No breaks were allowed and if mealtime came midway through the stir, men ate with one hand and stirred with the other.

It Takes All Sorts

A curious diversity of people arrived in the new town. Some were worldly and chose their destination carefully, while others simply ended up in town. Some came with money, while many others were almost destitute. An unfettered lifestyle attracted those who wanted to be free of family and societal expectations, while others arrived earnest and determined to succeed. Some, even then, had decided to spend their final years in Kelowna.

Rembler Paul, a man of “roaming disposition and an adventurer in every sense of the word,” retired to Kelowna in 1905. He brought his wife, Elizabeth, and his money, and built a large, stately home on Bernard Avenue. A full-time gardener was needed to look after the surrounding eight acres. Paul was seventy-four years old, unassuming in spite of his considerable wealth, and could frequently be found among the regulars at Lequime’s store. He was always recognizable by his large, and immaculately groomed, bushy white beard.

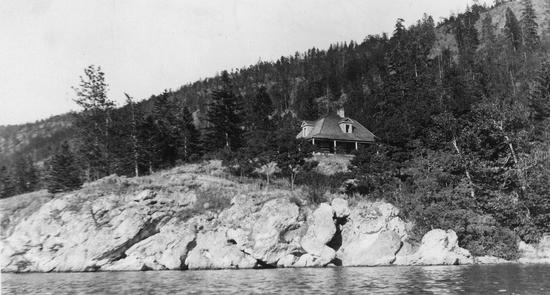

The couple’s son had died as a young man and though various of the four young grandsons visited occasionally, the Pauls were mostly on their own. Mrs. Paul became ill soon after their arrival and suffered the ravages of cancer for several years. Hoping to provide a quiet summer retreat for his wife, Rembler bought several acres of land along the lakeshore, about five miles north of town. A finely crafted log house was built on the property though Elizabeth only visited it once before she became too ill to venture that far from her bed in town.

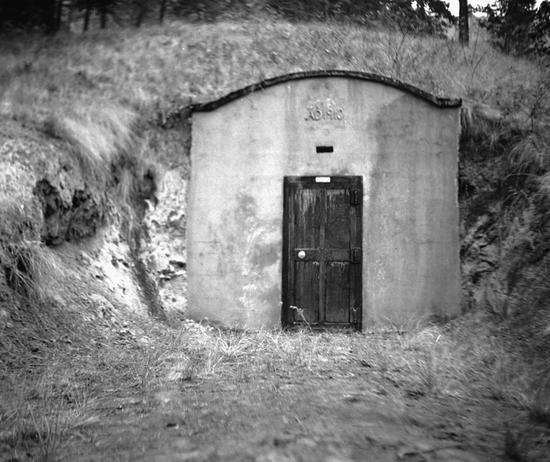

Paul wanted to pay tribute to his family in a unique way, and decided to have a substantial tomb built into the hillside, near the log house. The needed materials were transported by wagon and stone boat through what soon became the Glenmore Valley, and when the horses could go no farther, the large steel door, cement, boards, wire reinforcements, nails and equipment were lowered down the hillside by rope through a shale gully, onto a flat landing above the lake.

A vertical cut was made into a large mound of earth and a fifteen-foot excavation was dug back into the hillside. The opening, which was nine feet wide and seven feet high, was lined with concrete and two concrete shelves ran the length of a central passageway: there was room for eight coffins. The date, “AD 1910,” appeared above the vault’s large steel door, near the top of the cement façade, and the door was locked.

Elizabeth was eighty-three years old when she died in 1914. Rembler was devastated and was joined by the town’s leading citizens, “amid every manifestation of sorrow,” as they followed the coffin from the Anglican Church to the foot of Bernard Avenue. Once assembled, they boarded a flotilla of boats for the journey along the lakeshore to the tomb. The day was sunny, the lake calm, and the procession followed the grief-stricken old man up the steep hill from the lake. It was a memorable and profoundly sad occasion.

Rembler died in Edmonton two years later, having travelled to the northern city to winter with a friend. His body was returned to Kelowna by train and boat, and the town’s leading citizens again boarded small boats to follow the barge carrying Rembler’s casket to his tomb. The mourners glanced through the small glass-covered opening in Mrs. Paul’s copper casket as they lowered her husband onto his shelf, and reported that she looked perfectly preserved. Paul had left instructions and provisions for the tomb to be cared for, but this never happened. After a few years, vandals had destroyed the lock and access to the tomb became impossible.

The property changed hands a few times but was never occupied year-round, and vandals continued to destroy what was left of the house and access the tomb. A subsequent owner eventually demolished the house and had earth and rocks mounded over the face of the tomb. The City of Kelowna bought the property and created the Paul’s Tomb Park, which is accessible by boat, by trail from Poplar Point or from the lower Knox Mountain lookout. The paths all converge in a small open meadow that feels strangely peaceful. If one searches the low semicircle of hills at the back of the meadow, one may find the “AD 1910” on the tomb’s façade. Other than lilacs and the odd fruit tree, there is little evidence that Rembler and Elizabeth Paul ever existed, though they still remain quietly entombed in the park.

Early Kelowna attracted more than just the well-to-do and the earnest; it also had its share of bloody murders and violent deaths. On March 12, 1912, the escapades of Boyd James alarmed the whole valley. Boyd was a shifty character, an American army deserter who didn’t have much regard for Canadian laws. He came by his ruthlessness justifiably as his father was the brother and partner of the notorious American outlaw Jesse James. Boyd had been working for the Kelowna Land and Orchard Company for awhile and was known to a few locals. Deciding he’d had enough of orcharding, he headed to Charter & Taylor, the general store and post office in Okanagan Mission, one afternoon with his .45 Colt revolver drawn. He held up the three occupants, including a young boy, Randall, who quickly ran out the door, eluding the bullets Boyd fired after him, and headed for the bar of the Bellevue Hotel. A search party quickly headed out to apprehend the culprit but Boyd James had done his homework. His partner in crime, Frank Wilson, was waiting on the lakeshore with a boat, ready to depart.

The two men headed down the lake and appeared in Penticton a couple of days later. Word of the robbery had already travelled down the valley, and the two men were recognized in a bar, and arrested. The robbers had to be returned to the scene of the crime and were soon secured in irons. With Police Constable Aston as the escort, the trio booked into a stateroom on the SS Okanagan for the overnight trip to Kelowna. James and Aston got into a scuffle. The Penticton police had missed the revolver hidden in James’s shirt when they arrested him, and Aston was shot. James grabbed the key, unlocked their handcuffs, robbed their victim, took his gun and then casually headed to the dining room and ordered breakfast.

The Okanagan’s first stop the next morning was at Peachland. James and Wilson jumped onto the wharf before the gangplank was lowered and headed for the hills. The purser thought it curious, as no passengers were scheduled to get off at the settlement. An old-timer who had seen the pair earlier in Kelowna recognized them and was curious about their rapid departure. The purser thought they were stowaways and yelled at them to return. They kept on going. The old-timer headed to the ship’s saloon for the trip down the lake and walked in to hear the guests whispering about gunshots and muffled sounds. Seeing the women passengers becoming more and more nervous, he notified the purser. Upon investigating, Aston was discovered lying on the floor in a pool of blood with a bullet hole in his forehead.

The Okanagan soon pulled into the Gellatly wharf (today, in Gellatly Bay Park in West Kelowna), where the old-timer got off and telephoned back to Peachland to tell them of the murder and warn them about the fugitives at large. It was too late—the men had vanished. The alarm was spread with orders to catch the pair, dead or alive. Posses were organized, every trail and roadway was manned, and every beach was searched. There was no sign of the fugitives. The next evening, two men who had been camping at Powers Creek, near Westbank, came to town for their mail and supplies. Everyone was talking about the shooting and the story emerged about how the partners had encountered two weary men as they headed back to their campsite earlier in the day. The men had obviously been walking for some time and accepted the offer to share a meal, and then offered to pay for it. The offer was refused and the two men departed… toward Westbank.

Everyone was certain the two strangers were the fugitives. The men joined the posses, mothers kept anxious watch hoping no strangers came to their doors and wives cast fearful glances into the dark as their armed husbands scoured the countryside. The night turned to day and no one had been arrested. Finally, word came back down the lake that two armed ranchers had captured James and Wilson just as they sat on a log to rest. The capture had been made near Wilson’s Landing, about five miles north of the ferry wharf. The next time the prisoners found themselves on the Okanagan, they were securely bound and tied on the foredeck, and again headed to Kelowna.

Tales of the Okanagan’s greatest manhunt were told over and over again. Aston died, so the murder, the escape and the recapture occupied locals for weeks. On the day before his trial, James managed to saw most of the way through his shackles with a hacksaw blade he had earlier hidden in his shoe. A sharp-eyed prison guard noticed and spoiled the escape. The trial found James guilty of murder and sentenced him to death by hanging. The prisoner made one last desperate attempt to escape on the day prior to his hanging. Hoarding the black pepper that had come with his meals, the murderer blew it into the face of the guard as he opened the cell door. Though temporarily blinded, the guard had the wits to push James back into his cell and relock the door.

Justice was swift. James was hanged at the Kamloops jail on August 9, 1912, just five months after he had robbed the Okanagan Mission store. Frank Wilson was found to be an unwilling accomplice and was so fearful of James that he begged to be kept in custody until after the hanging.

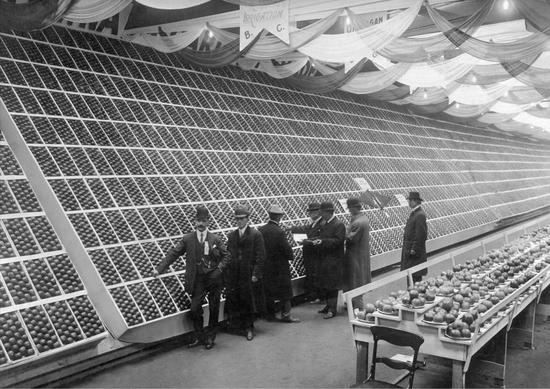

In spite of the intervening dramas, Kelowna’s business community continued to expand. Soft red bricks were made out of Knox Mountain clay and used in the new buildings along Bernard Avenue. Frank DeHart took fruit marketing to another level by convincing growers he could create displays that would not only showcase their apples but also increase awareness of the valley’s fruit-growing potential. This became a popular way to advertise the Okanagan’s orchards, especially when the displays won prizes in New Westminster, Toronto, London and Spokane, Washington.

It also took awhile for growers to decide how best to package their apples. Eastern orchards used barrels that held up to 150 pounds but they were heavy and difficult to handle. Washington state’s apple industry, the Okanagan’s nearest competitor, was using wooden boxes that weighed 40 pounds regardless of the size of the apples. Okanagan orchardists experimented with a larger box but ultimately decided the standard forty-pound American box worked best for them too. The boxes could easily be made locally. The tall, large-diameter ponderosa (yellow pine) trees covering the lower elevations of the valley had been named by David Douglas for their ponderous size. At seventy-five to ninety feet in height, the straight trunks of these trees were ideal for making fruit boxes as the branches started far up the trunk and the boards were generally knot-free. A vibrant new wooden fruit and vegetable box industry began and over the next thirty or so years, over 700 million wooden boxes were built and shipped out of the valley. So many boxes left the Okanagan that people throughout the province and on the Prairies started calling them “Okanagan furniture.” They were reused as bookshelves, cats’ beds, rabbit hutches, nests for hens, feed boxes for cattle, milking stools, children’s cribs, dressing-table vanities, desks and, when nailed to the shady side of a cabin, refrigerators.

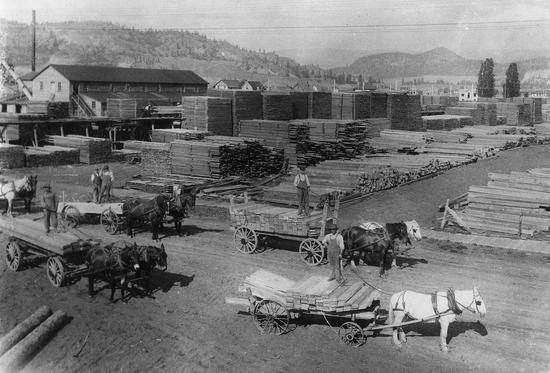

Early bush mills were set up near the forest and loggers cut the trees for horses to haul, by wagon or sleigh, to the nearby mill which was likely no more than a roof over a saw. If the trees were higher up the hillsides, horses would haul the logs to the cliffs overlooking the lake and drop them over, where they would be collected and towed to a lakeside sawmill. Logs would also be loaded into concave-shaped troughs at the highest elevations and sent careening down the hillsides into the lake. Liberal doses of bear grease were slathered over the troughs if there was a risk of the logs getting stuck, and by the time they reached the cliff above the lake they would be roaring along at a smoking sixty miles an hour. A lookout with bugle in hand would be posted wherever the chute crossed a road to warn of the impending danger.

Most communities in the region used wood-frame construction and the demand for lumber grew as more settlers arrived. As the apple trees grew larger, wooden orchard ladders up to sixteen feet tall were needed; expanding irrigation systems needed flume lumber; and more boxes were needed as increasing amounts of fruit was shipped out of the area. Various small sawmills made box shook—the individual parts of a box—and wrapped bundles of twenty-five different pieces with wire. Boxes were usually assembled by the packinghouses though some growers set up areas in their orchards and assembled their own boxes. Before long, a number of highly skilled box makers began following the ripening fruit up the valley and making boxes as they went. Each one had a workbench, specially honed axe handles and a uniquely organized work space. Box makers were paid on a piecework basis and the very best could assemble a thousand boxes a day. The ten dollars they made was well in excess of what almost everyone else was making at the time.

Stanley Simpson arrived in the Okanagan a few years before there was much of a demand for boxes and worked as a carpenter in Penticton. In the middle of the summer of 1913, Stanley and Mr. Etter, with whom he had been working, heard about a carpentry business for sale in Kelowna. The timing was opportune as their Methodist Church was planning a picnic in Kelowna and had booked the SS Okanagan for the trip. The two men took time out from the festivities and headed down Bernard Avenue, around the corner on Water Street and down the lane behind the fire hall. After looking at the shop and its equipment, they put twenty-five dollars down, arranged a loan for the remaining three hundred and bought the business. The new partners then rejoined the picnickers, returned to Penticton, packed up and moved to Kelowna.

The first few months of their new venture were promising but it wasn’t long before the economy slowed and World War I broke out. The partners soon realized the business couldn’t support them both and with a toss of a coin, the partnership ended and Stan took over. He scraped by doing whatever jobs needed doing: he built screen doors that were guaranteed not to sag, made odd bits of furniture, sharpened saws, repaired the jail and became known as a hard-working and reliable businessman. When the war was over and the economy picked up, S.M. Simpson Ltd. became a sash and door factory and moved along the lane to Abbott Street and into the fire-damaged Kelowna Canning Company building.

A few years later, Stanley, by now known as S.M., began buying rough lumber from different sawmills and from the independent loggers and started making apple boxes. He soon realized the risk of having to buy the lumber he needed from others and decided to get into the sawmill business himself. His first bush mill was set up with a partner and ran for just over a year before the area was logged out. The saw and shed were packed up and moved into another valley and then another, each time growing a little larger and adding a little more equipment. S.M. Simpson Ltd. had soon expanded into the sawmill business.

Box making usually began in March so a good number of boxes were on hand when the fruit was ready to be picked. Stan’s shop remained on Abbott Street but space was at a premium: long rough boards were brought in from the bush mills, passed through the windows facing City Park, re-sawn or planed to the needed size and sent on to the box-making area. Saw blades were thick so mounds of shavings, slabs and sawdust accumulated everywhere, including in the lane behind the building. The city’s curling rink had been built behind Stan’s operation and when the ice melted, he rented the building and stacked it to the rafters with wire-wrapped bundles of shook. It didn’t take long for the company to expand beyond apple boxes, and soon they were making specially sized prune boxes, plum crates, cabbage crates, cherry lugs and asparagus boxes that were lined with moss to keep the spears crisp. Over the next few years, Stan bought grape baskets and tin tops made of veneer from box makers on the Lower Mainland and resold them to the local growers for grapes, tomatoes and soft fruit.

The expanding mounds of sawdust and shavings were becoming an enormous challenge to work around as well as a growing fire hazard. The meandering Mill Creek was only a short block south of Stan’s factory and the surrounding land was waterlogged for much of the year and worse during spring floods. It couldn’t be built on and was of little value and up for sale. Stan bought several acres and carted load after load of the waste wood and sawdust to the area and spread it over the land, sometimes up to many feet deep. The area is now part of Kelowna’s Heritage Corridor and if homeowners dig down a few feet today, they will likely find the still-preserved remnants of the sawmill and box factory.

David Lloyd-Jones’s Kelowna Saw Mill was only a few blocks north of Stan’s sash and door factory and box plant. It had been in the same location since before there was a Kelowna and had remained successful by collecting logs from around the lake and storing them in booms just north of Bernard Avenue. Stan decided it made more sense to bring logs to the mill rather than taking the mill to the trees, as he had been doing. Before the war, plans had been in place to build a cannery on land adjacent to the summer camps at Manhattan Beach. The plan had been shelved, the land was for sale, and though it often flooded and was wet for much of the year, Stan knew he could make it work. Just as the Depression was about to unfold, he bought the property, called it his Manhattan Beach operation, hooked a telephone on a pole in the yard and finalized plans to build a sawmill, a box factory and a veneer plant.

To Kelowna—By Boat

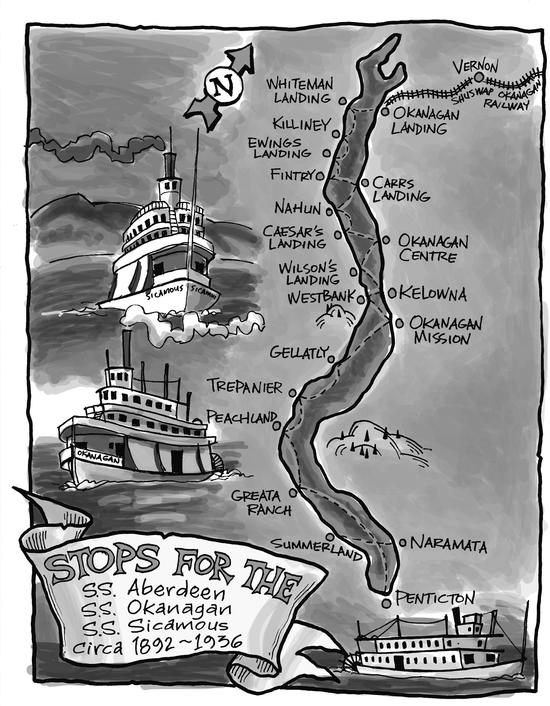

Kelowna, being at the midpoint of the Okanagan Valley, always seemed to have transportation issues. Vernon and Penticton were both railway destinations and had priority in accessing boats to carry both freight and people to their towns. Kelowna, on the other hand, struggled to make itself relevant in valley transportation plans. Canadian Pacific launched the SS York in 1905 to carry the freight that had been crowding passengers off the decks of the Aberdeen. It wasn’t long before the company’s wharf at the foot of Bernard Avenue became too small and though it had bought adjacent land, expansion opportunities were limited. The company began looking at the bays at the foot of Knox Mountain. Mindful of what happened to Prairie towns bypassed by the railway, the Kelowna Courier took the CPR to task, accusing it of pulling a grand bluff on the city in an attempt to find cheaper land. The newspaper called the railway committee “overbearing and arrogant” and accused the company of “soulless greed” and of being “an avaricious corporation.”

Whether the outburst convinced the railway to reconsider or not is unknown but it soon decided to buy the vacant land just north of the Kelowna Saw Mill. Construction got underway for a 315-foot-long landing slip, and freight sheds and new tracks were built across Water Street. The area was away from the business district but it wasn’t long before the packinghouses, canneries and fuel-supply companies took up the CPR’s offer to build spur lines for anyone who would ship on its railway. The area wasn’t large and it was quite an accomplishment for seven and a half miles of track to be wound around the buildings. Teams of horses were used to move railcars around the area as the company’s usual switching engines couldn’t work in such confined spaces. Two crews worked round the clock during the peak of the fruit season to keep the yard working and the barges efficiently loaded and unloaded before they departed for Okanagan Landing or Penticton.

The SS Okanagan, the lake’s second sternwheeler, was launched from Okanagan Landing in 1907. Vernon had again declared a half holiday to mark the momentous occasion and a large crowd gathered on the shore. Many passengers had already gone on board to experience the excitement of the launch and the inaugural trip. Everyone watched and those on board held their collective breath as the boat started down the slipway… and then stalled. It had become hung up on the stringers. The launch crew tried every imaginable manoeuvre to dislodge the vessel but nothing worked. The Okanagan remained suspended and the stranded passengers eventually had to be transferred to the nearby Aberdeen. No one seemed too worried and people soon departed for the Strand Hotel in Vernon to celebrate the launch that didn’t happen. The crew had much better luck the next day when the Okanagan quietly slipped into the lake, without an audience and without fanfare.

The CPR’s largest, most luxurious and last sternwheeler, the SS Sicamous, was launched in May of 1914 with even grander expectations than her sister ships. One of the largest paddleboats ever launched in BC, she was soon referred to as “The Queen of Okanagan Lake.” The ship was beautifully finished: five saloons were available to passengers, along with the main deck observation lounge, which boasted a grand piano; the ladies had their own lounge, while the gentlemen had a smoking room. The dining room was sixty-five feet long and two decks high; service was to the highest standard with crisp white linen, crystal and silver, and each table was graced with its own electric candelabra. Electric fans were kept on the sideboards to keep passengers cool during the summer while hot meals were prepared on the lower decks by three Chinese cooks and sent to the dining room by dumbwaiter.

The thirty-seven staterooms were accessed from the second-floor gallery, which wrapped around the dining room. Though the trip from Okanagan Landing to Penticton only took a few hours, the morning departure was early and passengers often boarded the night before, paid their $4.75, and enjoyed the superb service along with a good night’s rest. Those wanting to pay a bit less did without the ensuite bathroom and used the public facilities… which were, as was usually the case, emptied into the lake.

Sunshine streamed through stained glass skylights and the lounges and staterooms were finished in BC cedar, Australian mahogany and Burmese teak. Such elegance had never before been seen in the Okanagan Valley.

In spite of its stylish beauty and the luxurious travel it offered, the Sicamous also signalled the end of an era. World War I was declared a few months after the launch, lake traffic diminished and the Sicamous never lived up to its billing as transport for happy travellers and optimistic newcomers. Instead the boat’s whistle haunted the valley during the war. The boat carried news of the death of a son or husband and several short sharp blasts on the whistle as it approached a wharf signalled the return of a wounded soldier. Everyone within hearing distance would silently gather at the shore.

By the time the war was over, people could travel between Vernon, Kelowna and Penticton by car: Okanagan Lake was no longer needed to get from one end of the valley to the other. The CPR was losing money and withdrew the Sicamous from service in 1931, although the valley’s Boards of Trade complained so vigorously that the boat returned for another four years. In a further effort to cut costs, the CPR removed the ship’s top deck and the “Queen of Okanagan Lake” was reduced to being a fruit barge. Two years later, the Sicamous was docked at Okanagan Landing, and left to be buffeted by winter storms and baked by the summer’s heat for the next twenty years.

The valley’s two railways, the CPR and the KVR, provided service to both Vernon and Penticton and used tugs and barges to tie the two systems together. Laden barges were attached to the sternwheelers for a few years but it was a far from satisfactory arrangement and conventional tugs and barges were soon brought in as replacements. Boxcars were loaded directly onto barges that had been fitted with tracks. Most of Kelowna’s packinghouses and canneries were using the tugs and barges to ship their goods out of the valley by the early 1920s. The CPR increased its fleet to include the MV Naramata (1914), the SS Kaleden (1910), the SS Castlegar (1911) and eventually the SS Kelowna (1920).

Kelowna quickly developed a love affair with automobiles: they were both a curiosity and a menace. Roads were the still-used wagon trails and the noisy erratic vehicles terrified the horses and often sent them bolting into the bush. Bernard Avenue had been made wide enough for a horse-drawn wagon to turn around but when automobiles used the same street, its wide open spaces “encouraged” speeds in excess of the legal ten miles per hour. Drivers parked their cars wherever they stopped and then drove in any direction they wanted instead of keeping to the left, as they did in Britain. A letter to the city council pleaded that cars be banned from the streets for at least one day a week so “country folk” could come to town and not risk having their horses bolt.

The mail from Vernon came on the first car to arrive in Kelowna in July 1905. However, dirt trails made worse by rain left service so unreliable that horses were soon back on the job. The lack of roads did nothing to quell buyers’ enthusiasm and vehicles were often pre-sold long before they arrived on the wharf. Road travel northward was relatively easy but the primitive trail along the east side of Okanagan Lake was out of the question. On the west side, the narrow winding wagon road to Penticton challenged all car drivers. Most of the small boats and scows that carried cars and cattle across the lake travelled between Siwash Point on the west side and the wharf at the foot of Bernard Avenue on the east. The west side ferry wharf was called “Westbank,” which caused some confusion as this was also the name of the town six miles to the south. The route between the two wharves was known as “the Narrows” as it was—and is—the narrowest part of Okanagan Lake. This was also the point where the lake usually froze and ice accumulated in the coldest of winters. When the first government ferry service between Westbank and Kelowna was offered in the mid-1920s, the public was assured that the boat would be “armed with devices designed to repel attacks from the Ogopogo.”

Len Hayman, one of Kelowna’s legendary and more colourful characters, captained a succession of ferries across Okanagan Lake. The Aricia was one of the more substantial at twelve and a half tons and was equipped with a passenger cabin, a pilot house and, uniquely, a lifeboat. When demand increased and included cars, Hayman added a scow that could carry up to eight vehicles. Though he was well experienced, he still ran into trouble on the unpredictable lake. On one memorable trip, the captain cast off from Kelowna into a stiff wind with six cars and nineteen passengers. All was well until he was just about to pull into the Westbank wharf and was broadsided by a swift gale from the north. Even with the engine at full throttle, there was little Hayman could do: he cast off the scow and its cargo of automobiles and then fought to keep the boat away from the rocks. The scow bounced off the boulders and disappeared down the lake.

The passenger boat, however, hit the rocks and stuck fast. Waves washed over the stern, the lifeboat filled with water, and then the gas line broke and the passengers were being gassed. They panicked. Hayman threatened to throw them all overboard if they didn’t shut up and behave properly, and he finally managed to lower the lifeboat, bail it out and get the passengers to shore. One of the few who had managed to maintain his composure was dispatched to the dock to telephone one of the captain’s friends in Kelowna with orders to bring over another boat. When the friend arrived, the pair headed down the lake to collect the scow. Even with the drama, all passengers and cars were delivered to the Westbank dock only an hour and a half later than their scheduled arrival time. But when the travellers collected themselves and their belongings to continue their journey south, they soon discovered all was not well. The road from the wharf was blocked by trees that had succumbed to the same northerly gusts that had sent Captain Hayman and his ferry onto the rocks. Some likely thought it would have been better to have stayed at home.

Fifteen years later, the Aricia was replaced by a vehicle ferry, the MV Kelowna–Westbank, a wooden-hulled vessel with a fifteen-car capacity. It wasn’t long before the boat became known as the MV Hold-up because the service was so bad. When the lake froze over or ice jammed the Narrows, no sailings took place, mail wasn’t delivered and stores weren’t supplied. People walked if they wanted to cross the lake, or found a horse and sleigh or perhaps a motorcycle and sidecar to carry them to the other side. The incensed public had little influence on the government in Victoria and inadequate service was the norm for the next twelve years.

Finally… Kelowna’s Railway

British Columbia’s economy boomed between 1911 and 1913 and rail companies promised to lay new track all over the province. Most needed the provincial government to guarantee their loans, but that wasn’t a problem, and it looked like the long-anticipated rail line to Kelowna would soon be a reality. The Canadian Northern Railway bought land for a rail yard in Kelowna’s north end in 1912, and during the next two years completed surveys, purchased rights-of-way and started work on the grading and bridges. The route to Kelowna would run south from Kamloops, through Grand Prairie (Westwold), Armstrong and Vernon, and on to Kelowna. The provincial debt soon ballooned out of control, however, in part because of its railway loan guarantees, and most rail construction ceased.

Right after the war, railways’ finances were in such disarray that the federal government forced amalgamation of five of the most financially troubled railways, the Canadian Northern among them. The new company became the Canadian National Railway (CNR). Work on the Kelowna line picked up where it had left off five years earlier; things moved a little faster than anticipated when the CPR agreed to share part of its track along the route. The railway’s arrival was a historic and long-awaited event and plans were made to ship the 1925 fruit crop directly from Kelowna. The city was abuzz with speculation about the location of the new passenger depot. Since the two rail companies were now working together, everyone hoped the CNR would build its terminal near the CPR passenger wharf so boat travellers could easily transfer to the train. There was a limit to the co-operation, however, and CN carried on with its original plan to build a terminal closer to their rail yards. The city fathers were dismayed as they were certain it was too far from the business district to be well used.

The construction crew was still laying track about a mile and a half from the terminal on the morning of Thursday, September 10, 1925. A civic holiday had been declared for that afternoon, to welcome the first train, and all of Kelowna was encouraged to celebrate the momentous occasion. However, as the Kelowna Courier later reported, there was a “proverbial slip between the cup and the lip”—the track sagged just as the engine crossed the city boundary and the train tipped over at a precarious angle. The spongy railbed was apparently caused by nearby Brandt’s Creek and a previously undiscovered Native burial site. The celebration was cancelled, all work on the track ceased and a “gang of husky labourers strove with such appliances as were at their command to right the engine and get it once more on the rails.”

Undeterred, 1,500 citizens showed up again the next day to celebrate the train’s actual arrival and schoolchildren were happy to have another holiday. Mayor Sutherland joined railway dignitaries to hammer the ceremonial golden (actually gilded) spike into place as the jubilant crowd showered the construction crew with apples and “luscious musk melons.” When the train’s whistle sounded promptly at three o’clock as the engine pulled into the station, it was answered by the whistles of all the factories around town. Kelowna had good cause to celebrate: the Shuswap & Okanagan Railway had arrived in Vernon thirty-four years earlier and the Kettle Valley Railway had chugged into Penticton ten years earlier. Finally, it was Kelowna’s turn.

CN passenger service began a few months later with an oil-electric car, and passengers likened it to a long-distance streetcar ride. The trip to Kamloops took four hours and forty minutes and included a stopover in Vernon for lunch. When the demand exceeded the capacity of the initial car, it was replaced by a steam train with first- and second-class passenger, baggage and express service. The CNR then built a wharf half a mile north of the CPR wharf and added tug and barge service, using the Pentowna, the Radius and three other tugs identified only by number.

Jolly Good!

The Okanagan in the summer looked like one great sports field. Competition was fierce as each community fielded lacrosse, baseball (rounders), football (soccer), rugby, tennis and cricket teams. Sometimes the same people were on every team. Many arrived in the Okanagan after some years in the British military and brought horse racing, polo and gymkhanas with them. The first golf tournament on the BC mainland was held in Kelowna in 1899 on a small course just north of Bernard Avenue and east of the Kelowna Saw Mill. This was built around marshes, downed trees and the few remaining pines, but the Vernon News nonetheless observed that “we anticipate that Kelowna will some day be as well known for golf as for tobacco, cricket, or any other games or vegetables.”

The Bankhead Orchard Company had set aside sixty acres of undulating meadow by 1914 for a nine-hole course, and imported a greenskeeper from St. Andrews, Scotland. Little happened during the war but by 1920 the interested agitated for a better facility. The Kelowna Golf Club was soon formed and, after searching around the community for a suitable site, it purchased land across Glenmore Road from the town’s original course for the “huge” sum of $5,500. The shack that had previously housed the Chinese men working in the orchard was fixed up for a clubhouse though a toolshed was built closer to the first fairway with a “Ladies’ Toilet” attached. The men were apparently left to their own devices. The club’s board felt such confidence in their course that they placed an advertisement in the CPR pamphlet Golf in Canada, 1921–1922. They noted that their “humble club house [was] somewhat lacking in refinement.”

The Kelowna Regatta

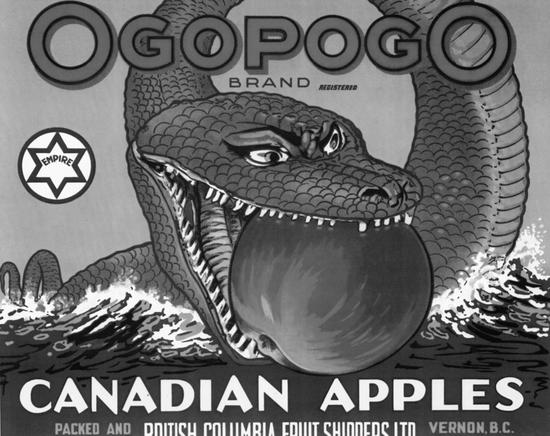

It was about 1924 when the non-Native community took over N´ha-a-itk and transformed the fearsome lake monster into Ogopogo. The name came from a popular British music hall ditty: His mother was an earwig, His father was a whale, A little bit of head, and hardly any tail, And Ogopogo was his name. The renaming also transformed the legendary fierce monster into something more benign… and vegetarian.

In usual fashion, each valley community has claimed Ogopogo as its own. The dispute led to hard feelings when Kelowna’s statue of Ogopogo disappeared from its pond at the foot of Bernard Avenue. The creature, minus its tongue, was discovered in an army hut in Vernon a few weeks later. No one admitted to any wrongdoing, though the Ogopogo was soon embedded in cement to make sure it stayed “home” in the future. Sightings of the monster were often dismissed as Regatta publicity stunts, as most sightings were during July and August… but then again, isn’t that the most logical time for the creature to be about? Winters were surely spent hibernating, and when the lake was frozen, it couldn’t have surfaced. Many “responsible non-drinking citizens” were convinced that Okanagan Lake was home to some kind of curious aquatic creature, and that remains true today.

British settlers also brought their English regatta traditions with them, and by 1906 the first Kelowna Regatta was underway. Soon it became the city’s signature summer event. Spectators gathered on the CPR wharf to cheer on the sailors, canoeists and rowers in the bay though it wasn’t long before the crowds grew and spread farther along the beach to the original Lequime wharf and warehouse. The Kelowna Aquatic Association Ltd. was formed a few years later and sold twenty-five-dollar shares to pay for a pavilion and diving stand a little farther along the beach. Separate bathing cubicles for women were built west of the pavilion, while men had to use the boat storage space under the pavilion.

The Kelowna Regatta had already become a two-day festival by 1912 and was attracting over two thousand spectators. A tea room was added along with an eight-hundred-seat grandstand, with “KELOWNA” painted on its roof. Competitors “tilted” each other out of canoes and challenged each other in the swim across the lake, and children scrambled to catch a greased pig that had been dropped into the water. The pig always managed to evade the swimmers by squealing off into the park with the children in hot pursuit. Gas launches and sailboats continued to compete, though the war canoe races generated the fiercest rivalries. Men’s, ladies’ and mixed teams gathered from throughout the valley and the races were often so close that spectators would be leaping out of their seats, yelling themselves hoarse, with enthusiasm. Evening shows were added to the sporting events with displays of gymnastics and the “high-kicking” Gladstone sisters, who were also appearing at Kelowna’s Dreamland Theatre. In the usual Okanagan tradition, a ball wrapped up the event. Kelowna summers and the Regatta were inseparable for many years to come.

Around the Town

Okanagan Mission

Kelowna was still not much larger than the original Lequime acreage when the neighbouring areas began to take on their own unique identities. Okanagan Mission became a magnet for all things British and since it could only be reached along the muddy and often disappearing Swamp Road, it happily developed on its own. Even after an alternative route from Kelowna was built in 1912, the road was so close to the lake that cars were usually mired in sand during the summer and overwhelmed by snowdrifts in winter. It remained that way for years.

The South Kelowna Land and Orchard Company lavishly promoted the area and British settlers came to clear land or take over the properties of those who had come before. They built large homes and planted orchards; they also build drying sheds for their tobacco crops. The post office moved to the Bellevue Hotel, the Okanagan Mission Supply Company was nearby and St. Andrew’s Anglican Church was consecrated in 1911. The townsite was essentially complete when the school moved from its earlier Swamp Road location to the lot across from the church. The wharf at the foot of the road to the Bellevue Hotel (the original Thomson home) had the Aberdeen, York and Okanagan dropping off freight and passengers. Access to the hotel was easy and its elegant dining room and well-stocked bar soon became the social centre of the community.

Okanagan Mission’s heyday was during the construction of the Kettle Valley Railway. The MV Kaleden delivered large caches of dynamite, powder and other supplies to the wharf, which were then loaded onto wagons and hauled past the Bellevue and up the hills to the construction site. A tent camp for workers was built behind the hotel along with a makeshift hospital staffed by a doctor and two nurses. Residents were aghast at how the construction workers’ behaviour transformed their usually sedate community. A statuesque blonde, soon known as “Lady Godiva,” took to riding her great white steed along the lakeshore with little other that her flowing locks to cover her. Construction workers told the story of the fellow who was heading back to camp carrying a large amount of whisky, along with his half-empty flask. The climb was long and he was tired and soon lay down for a snooze—and was found later in the winter, frozen solid.

Then there were the three young fellows who lived in what was known locally as “Buckingham Palace”… really a precarious lean-to. Having time on their hands after a Saturday afternoon at the bar, they spent the evening using their neighbour’s chimney for target practice. Their aim wasn’t the best and their neighbours had to avoid the area for hours. The Ritz Hotel was at the bottom of the Mission hill and the resident ladies were apparently available to entertain anyone passing their door. During the languid days of summer when the unrelenting heat made life almost unbearable, the ladies were known to cool off by slipping into the irrigation ditch running along in front of their hotel and St. Andrew’s Church. The water inevitably dammed up and overflowed onto the road, and those attending church would have to navigate through the mud and puddles.

The Countess Bubna of Austria, owner of the Eldorado Ranch, built a half-timbered, gabled luxury private hotel on the lakeshore in Okanagan Mission in 1926. Named the Eldorado Arms, it was to accommodate her friends and the friends of friends who came to visit: if she liked them they didn’t have to pay but if she didn’t, or their connections were too remote, they paid for the honour of staying at her hotel. Bathrooms were communal, verandas were screened, tea was presented on the lawns and the staff quarters housed the retinue of servants who accompanied the guests. Visitors more or less disappeared during the Depression and the hotel opened to the public. A few people, usually spinsters or widows, arrived from Kelowna each summer to spend a few weeks or even most of the summer in the small upstairs rooms, enjoying the gradually fading elegance of the lakeshore hotel.

Though Mission residents sometimes talked about officially incorporating as a town, nothing ever came of it. A letter appeared in the Kelowna Courier in 1930 from a disgruntled resident who complained about the area’s unjustified reputation as being the home of the idle rich. Most residents, it stated, including the letter’s author, were simple farmers who were paid the same for their crops as anyone else in the valley, and the comments were mean-spirited and ill-founded.

Rutland

Settlers from the Prairies and overseas continued to arrive in the Rutland area, and they bought land and planted orchards in the surrounding communities: Black Mountain, Hollywood (after Hollywood, California), Joe Rich (after a pioneer settler) and Belgo (after the Belgian Orchard Syndicate), which were more geographic areas than communities, though some had their own schools. Before long the Rutland townsite attracted a collection of small stores, a school, a post office and churches. The Farmers’ Exchange packed apples for a number of orchardists until McLean and Fitzpatrick set up their own packing operation and marketed their apples under the Zenith Brand label. When the CNR built its tracks through Rutland, Mc & Fitz, as they became known, moved their plant to the rail line. These were challenging times for the newcomers: some years were plagued by drought, or apple scab and low apple prices. Many took jobs off the farm because they needed the income while others grew onions, tobacco, asparagus, raspberries or flowers and seeds. The Cross Cannery was built adjacent to the rail line and became the first in the area to can locally grown asparagus.

Kelowna’s Chinatown shrank as the early share-croppers grew older and the federally imposed Head Tax cut off the flow of new immigrants. Yet Kelowna’s Asian population grew when Japanese residents in Vancouver were confronted by anti-Asian riots in 1907, and many decided to leave the city. When the labour bosses from Vernon’s Coldstream Ranch went to Vancouver to recruit workers, many Japanese families came to the Interior and some moved south to Rutland. They too had originally come to Canada expecting to strike it rich and return to their homeland. Instead, their reality became back-breaking labour and share-cropping on the area’s vegetable farms. Some returned to Japan to marry or arranged for brides to sail to Canada; their children attended local schools along with Japanese school, where they learned their country’s history and traditions. These families were usually frugal; they lived with few comforts, endured being strangers in a sometimes unwelcoming community and relied primarily on each other.

The first Indo-Canadians, mostly Sikhs from the Punjab, were hired by CPR labour recruiters in India and came to Canada to build the railway. Many of those who stayed in BC gravitated to Vancouver and found work in the sawmills; others drifted into the Fraser Valley and the Okanagan to work on farms and orchards. Some returned home but many who stayed experienced the growing anti-Asian violence in Vancouver. The animosity had begun to spill over to the Indo-Canadian community by 1914, and some chose to leave the coast and settle elsewhere, including in Rutland and Ellison, near Kelowna. Starting out as share-croppers, many new arrivals bought a few acres of bush, cleared and planted, bought more, repeated the process and grew acres of vegetables. They arrived expecting to work hard and did, and then infused their children with the same work ethic. They bought more land, sent their children to local schools, expanded their business interests and gradually became involved in their new community. By the beginning of the 1930s, Rutland had an ethnic diversity that was noticeably lacking in the other neighbourhoods.

Glenmore

The Central Okanagan Land Company continued to market its Glenmore properties in Toronto and Montreal. In spite of a fair number of settlers arriving from Britain, the area didn’t have quite the same cachet or notoriety as Okanagan Mission. The Glenmore newcomers seemed much more earnest, and intent on getting their orchards planted and properly irrigated. Flumes were generally routed near the homes with a pipe and tap either in the yard or indoors. When the irrigating season came to an end, nearby cisterns were filled to ensure families had water over the winter. Drinking water was another matter, and for many years Glenmore residents carried five-gallon milk cans or barrels in the back of their pickups whenever they came into Kelowna. A drinking-water tap was installed across from the Kelowna Golf Club so drinking water could be collected on their return trip.