Chapter Six: Kelowna Grows Up—The Tumultuous Years, 1955–1975

The next few decades were tumultuous in many parts of the world: there was the Cuban missile crisis, the Vietnam War, the Berlin Wall and, in Canada, the Quebec crisis. BC celebrated its centennial and the Social Credit Party defined provincial politics with Kelowna’s MLA, Premier W.A.C. Bennett, as its leader. The province opened for business as new highways, bridges, railroads and mega power projects were built: BC stopped being the “blight on Confederation,” as that earlier Royal Commission had labelled it. About nine thousand people lived in Kelowna in the mid-1950s, though that number would double over the next twenty years and the community would be challenged to keep up with the growth.

Kelowna was also modernizing and updating its image. Apartment buildings began replacing the stately old houses along Pandosy Street. Hochelaga, the spacious home of the Bank of Montreal’s manager, was torn down and replaced with a four-storey building of the same name. Dr. Knox’s elegant home, just down the street, was also replaced by apartments. The 1930s art deco post office was no longer large enough, and before the community understood that such buildings were an important part of its heritage the imposing white stucco building, with its shiny marble floors and bronze wicket grates, was demolished.

In the early days, Kelowna made do with makeshift courtrooms over bakeries, in CKOV’s old studios, in a converted house just off Bernard Avenue and in city hall committee rooms. The mayor led a delegation to Victoria in 1950 demanding that adequate court and police facilities be provided for the city. Four years later—and after considerable negotiation with S.M. Simpson to get his agreement to put the provincial building on the civic centre lands—Kelowna’s new court house opened in 1955. The L-shaped building occupied the lakefront across from city hall until it was torn down in 2001; the property is now part of Stuart Park. As part of the negotiations to build on city property and acquire the court house site, the province exchanged land near what is now Kerry Park along with the promise to build a double ferry slip at the foot of Mill Street (now Queensway) and a seawall along the shoreline to accommodate the new Kelowna Yacht Club. A narrow boat launch and a parking lot still occupy the old ferry wharf site, the seawall is part of the walkway joining City Park with Stuart Park and the yacht club remains in its original location, though they have bought the property immediately to the north from the city, and will be relocating their clubhouse.

Convincing the province that Kelowna needed its own court house was a long and challenging process. Its genesis dates back to 1948, when BC’s chief justice, Wendell Farris, came to town to officiate at a hearing. The courtrooms were then on the third floor of the old Casorso Block on Bernard Avenue. There was no elevator and the judge had to walk up three flights of steep stairs to preside. He was so exhausted and so mad he declared the Supreme Court would no longer preside in Kelowna, until the community provided facilities befitting the dignity of his court. It took seven years of hearings in the Vernon Court House before the court would return to Kelowna.

Kelowna General Hospital became so overcrowded that single rooms become doubles and four-bed wards became five- and six-bed wards. Closets were transformed into offices, buildings that should have been torn down were renovated and psychiatric services and physiotherapy were offered for the first time. Practical nurses and lab technicians were being trained as a great variety of specialists joined the staff. After much deliberation, officials also decided the elderly were entitled to specialized care, and since many were occupying the acute care beds so badly needed by really sick patients, it made sense to build a facility just for seniors. Kelowna’s first extended care unit opened in 1970 and signalled a major change in the treatment of the elderly. It wasn’t long before a fourteen-acre orchard and greenhouse operation was purchased, just a few blocks east of the hospital, which would become the Cottonwoods Extended Care facility.

Early Kelowna had been small and compact, and city council never begrudged spending money for education. Schools in town were overflowing, and as people moved beyond the downtown core the new neighbourhoods needed their own facilities, including junior and senior high schools in Rutland, Glenmore and Okanagan Mission. The nature of education changed as well, as the province took over both school funding and curriculum planning.

Kelowna Community Theatre

Kelowna’s cultural opportunities also improved in the early 1960s. A small group of like-minded citizens spearheaded a fundraising campaign to build a community theatre. The Empress Theatre on Bernard Avenue had been built in 1919 and had served the town well. A number of tenants had used the building, including a bank, before it was renovated to fill in for the burned-out opera house and host the Gilbert and Sullivan shows that toured the Okanagan. Yet its basement dressing rooms were so small and so inadequate for those performances that the forty or fifty performers had to expand to the back rooms of Chapin’s Café next store. Famous Players took over the building in 1930 and brought movies to town. A matinee ticket to see the likes of Tarzan, Charlie Chaplin and the Wizard of Oz on film cost fifteen cents. The theatre was also used by community groups, including the fruit growers and their often raucous meetings, even once the new Paramount Theatre was opened in 1949. Though Kelowna relished the luxury of the two theatres, the Empress stopped being a theatre in 1957. The cultural vacuum was immediate.

The citizens’ committee set out to raise $35,000 of the $80,000 needed to build a new theatre. The city promised funds, but only if the community came up with the initial amount. The balance of the money would come from a Winter Works program. Many were vocal in their support of the arts and various theatre groups emptied their bank accounts, but the campaign didn’t reach its goal. A second campaign wasn’t much more successful, but taking a leap of faith the committee decided to build anyway. S.M. Simpson Ltd. owned the lumber yard across from city hall and sold a portion of it to the city at a “very nominal price.” The sod was officially turned, the stage and the balcony were deleted from the plans and the building went up, with the community pitching in. The stage was built later by local carpenters who volunteered their time, civic employees did the landscaping in the evenings, truckers hauled fill and topsoil to the site at no cost, the town’s painters painted and school janitors cleaned and installed the seats. The Kelowna Little Theatre bought 250 seats from the old Empress Theatre, and another 400 were donated by Famous Players and R.J. and Bill Bennett, who had bought the old building. Lighting fixtures were also salvaged from the Empress, along with some carpeting and an old piano. It truly was a community theatre.

The official opening was a grand event. Tickets were a “very reasonable” ten dollars each and Teresa Stratas, the vivacious twenty-four-year-old Metropolitan Opera star who was making her mark at “music’s dizzying heights,” reduced her customary fee for the concert. She declared she did so for “all Canadians and for this theatre.” Miss Stratas had previously performed at the 1960 Regatta evening show and was fondly remembered. Citizens were elated: it wasn’t often that a concert of this calibre was available without travelling to much larger centres. If there had been a curtain to raise, the committee would have raised it, but the theatre was still short of a few finishing touches. Some of the wiring hadn’t been completed, the heating hadn’t been installed and the dressing rooms were marginal, as were the stage fittings. The Royal Winnipeg Ballet came to the rescue and loaned the theatre a blue and black velvet backdrop, which was hung to create a stage for the performance.

Students attended a special matinee but it was the gala evening performance that was sure to be remembered. Over eight hundred attended—“the cream of Kelowna’s society”—many of whom had been entertained at one of several private dinner parties that added to the important occasion. The high school band serenaded as car after car of glamorously gowned women and their escorts arrived as dusk settled on the September night. The entrance had been framed with flowers and Mayor Parkinson, escorted by the Legion Pipe Band, entered the lobby wearing his chain of office and ceremonial robes to officially receive the key to the theatre. It was surely the most glamorous event in the city’s history.

Quong’s—A Favourite

Other than the Royal Anne Hotel, there were few elegant places to eat in Kelowna. There were various Chinese restaurants, including the Golden Pheasant and the Green Lantern, but the City Park Café—or Quong’s, as most people called it—was in a league by itself. It likely had its origins in early Chinatown, maybe 1906, and was just down the street from the Dart Coon Club, the Chinese Masonic Hall. Opinions varied about those early years and whether the café was a quiet, gracious eating place or a brawling, opium-infested dive. Several members of the Quong family ran the restaurant at various times and while the rest of Kelowna closed their doors at 9:00 p.m., Quong’s stayed open as long as there were customers. Sometimes those arriving for breakfast met those departing at the end of their evening. The T-bone steaks were fried directly on the top of the cast-iron wood and sawdust stove. They were the best in town. The menu had a selection, but people only ever talked about the steaks.

The café became Kelowna’s late-night social hub during the 1940s and through the 1950s, especially for New Year’s Eve and during the Christmas holidays. Anyone and everyone in town for Regatta would eventually show up at the café. Election nights drew every candidate and all their supporters. No one would call the police because most of them were at the party too. Quong had a sixth sense about his guests and if he figured they were likely to become a bit rowdy, he marched them straight through the restaurant to the Blue Room. It was blue because of the kalsomine paint; a single light bulb dangled from the ceiling and one long oilcloth-covered table ran down the centre of the room. The chairs were mismatched and if there weren’t enough, large pieces of log were pulled up to the table. Matching chairs didn’t matter because they rarely lasted long. Booze was usually smuggled in but if you arrived with none, a pot of “tea” could be arranged.

The more respectable front part of the restaurant had booths for privacy with curtains that could be closed or left open depending upon how much you wanted to remain in or out of the public eye. They weren’t very effective as patrons were known to stand on chairs and just peer over. If a party got going, a couple of shoulders against the wall of the booth would usually demolish it. Quong was always unperturbed if an unexpected crowd arrived, as helpers and cooks just showed up and partiers never hesitated to pitch in and help in the kitchen. Rumours flew about the upstairs rooms where teens might sleep off too much party or about the man who frantically tore down the stairs only inches in front of a screaming woman brandishing a meat cleaver. A fan-tan game ran constantly in the back room. No one worried about a police raid: three of the officers were among the best players.

Quong’s closed in 1964. It was the end of an era and the end of an institution. Over fifty of the town’s leading businessmen, politicians and police presented Wan Quong, the last of the Quong family to run the café, with a gold engraved watch.

W.A.C. Captures Centre Stage

W.A.C. Bennett was full of optimism and convinced that anything was possible with proper planning. Long a student of finance, he felt obligated to wisely manage taxpayers’ dollars and became his own minister of finance. The Canadian economy was strong during his years in office, but BC’s economy was booming. Highways, tunnels and bridges were built, as was a railway to the north (the Pacific Great Eastern, and subsequently BC Rail), and the population grew faster than anywhere else in the country. Foreign capital flooded into the province, everyone was working and the standard of living kept improving. This new economy needed an educated and skilled workforce and both Simon Fraser University and the University of Victoria were created, as were a number of technical colleges. Bennett was a staunch defender of free enterprise but he had no hesitation about stepping in if the private sector didn’t deliver.

Bennett always talked about balanced budgets and his “pay as you go” mantra infused his politics from the beginning. The province’s direct debt was eliminated after Social Credit had been in office for just seven years. Even though many suggested that was accomplished by fancy bookkeeping or handing the debt off to a variety of Crown corporations, Bennett decided to celebrate.

It was an exuberant party. Armoured cars transported $70 million of cancelled bonds to Kelowna in the summer of 1959, piled them onto a floating barge and dragged them out into Okanagan Lake. Hundreds of dignitaries arrived in town, cabinet ministers were delirious, townsfolk rejoiced, media from around the country converged and thousands of schoolchildren sang “Happy Birthday” to their Mr. Bennett. As the sun began to set, the premier and his cabinet clambered aboard a flotilla of boats and headed out onto the darkening lake. The bonds, having been soaked with gasoline and secured with chicken wire, were waiting. At the appointed hour, Bennett fired a flaming arrow toward the barge. Some suggested the arrow reached its target but bounced off and fell in the lake. It didn’t really matter. Nothing was left to chance as an out-of-sight RCMP officer took out his lighter and lit the fire from the back side of the barge. Thousands celebrated for hours, and the next day’s newspaper shared photographs of the party with its readers while its headlines told of BC’s much envied debt-free status. Everyone, including the premier, had wonderful time.

The celebration marked the midpoint of Bennett’s term in office. The first Home Owner Grant was introduced at this time, along with provincial parity bonds—the precursor to Canada Savings Bonds—as a way to generate the capital needed to fund future development. A modern transportation system was in place but Bennett recognized that a cheap, plentiful source of energy was needed to fuel future growth. The Two Rivers plan soon emerged to develop hydroelectric dams on the Columbia and Peace Rivers. Partnerships were formed, and cross-border negotiations were lengthy and mired in red tape. BC Electric, the distributor of the bulk of the province’s power, refused to commit to buy the power generated by the Peace project, and Bennett was furious. The company’s board of directors refused to change their position, and since they were controlled by Ottawa, Bennett was even angrier. He took over the company on the day following the death of its well-respected president, “Dal” Grauer, and formed BC Hydro as a new Crown corporation.

The W.A.C. Bennett Dam on the Peace River was completed in 1968. It was the largest earth-filled structure ever built at the time and the only public works project built by his government to bear the premier’s name. BC Hydro went on to build a number of dams and generating stations on the Columbia River, including the Mica and Revelstoke Dams. Bennett negotiated treaties with the US government that he felt served BC well, though his involvement didn’t endear him to the federal government: he knew that his job was to look after his province, and if other levels of government didn’t like it, that was their problem.

W.A.C. generally let his cabinet members run their own ministries and focussed his energies on building a bigger and ever-grander BC. His leadership was unchallenged during his tenure and the forty-seven percent of the popular vote his party received in 1969 was unprecedented. He had established a pattern of calling elections every three years, and in 1972 no one, least of all Bennett himself, expected his time in office would be over. Everyone was in shock: Le Monde in Paris commented, as did the Guardian in Britain. The New Democratic Party (NDP) the successor to the CCF, took thirty-eight seats, the Liberals five and the Conservatives two, which left the Social Credit Party with ten. Eleven senior cabinet ministers lost their seats, though Bennett himself won his eleventh straight constituency election.

Though there had been no talk of retirement, Bennett was seventy-two years old. He had been in power longer than any other political leader in North America. Was he suddenly out of touch with voters? BC had become “Lotus Land,” and perhaps people wanted still more and didn’t think he could go on delivering. The NDP, under the leadership of the charismatic Dave Barrett, campaigned on the slogan “It’s time for a change.” Voters apparently agreed. Bennett had long campaigned to keep “the socialist hoards away from the province’s gates,” but organized labour had influenced voters. With ineffective Liberal and Conservative parties, the province had become polarized into two feuding political regimes. BC has a habit of voting out rather than voting in, and maybe it was just time for a change.

W.A.C. Bennett was unquestionably a larger-than-life politician. He provided inspired leadership, which propelled his province to become bigger and richer and more confident than most people could ever have imagined. W.A.C. would have rather died in office. He said he could take “hecklers, brickbats and criticism better than the praise” he received at the end. He led the Social Credit Party in Opposition for ten months though he rarely appeared in the legislature.

Bennett hadn’t planned for his son, Bill, to take over his party and didn’t endorse him when he ran for the leadership. When Bill became the new Socred leader, W.A.C. wasn’t happy with the minor and behind-the-scenes roll he was assigned. The senior Bennett died in his sleep in 1979; he was seventy-eight years old. Funeral services were held in Vancouver and in Kelowna, where over a thousand people crowded into and around the First United Church and lined the nearby streets. The coffin was draped with the sun-emblazoned provincial flag, the flag that had been created when W.A.C. was in office, and flanked by bagpipers and an RCMP honour guard. It was truly the end of an era.

The Unexpected

During these years, Kelowna was astounded to find itself dealing with several random fires and numerous incidents of unprecedented violence. Just after St. Theresa’s Catholic Church in Rutland opened in 1949, it was destroyed by arson. Two nearby rural schools and large stacks of wooden boxes, awaiting the harvest, also went up in flames. A Doukhobor family living in the area was able to escape before their home and barns were torched. Though it had been quiet in the Okanagan during the early 1950s, a section of the Kettle Valley Railway near McCulloch, close to Kelowna, had been blown up just as plans got underway for the official opening of the new Okanagan Lake Bridge. With the impending arrival of both Premier Bennett and Princess Margaret, all symbols of authority seemed to come under attack.

A month before the bridge was to open in June 1958, a bomb exploded in the beer parlour of the Willow Inn Hotel. The police arrived to find a gaping hole in the wall of the men’s washroom, the door hanging by a hinge, the ceiling and support beams shattered, and the night watchman emerging from the dust. Another bomb was discovered before it exploded in the beer parlour of the Allison Hotel in Vernon, a power pole was blown up near Armstrong and a third bomb was discovered on the MV Lequime ferry. The deckhand who discovered the bomb in the back of a toilet was so startled he threw it overboard. He subsequently confirmed it looked much like the bomb found at the Allison Hotel—a sealed glass jar containing dynamite and nitroglycerine that had been wired to a cheap pocket watch.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, thousands of Russian Doukhobors had fled religious persecution and resettled in Canada. Most homesteaded on the Prairies but some found the climate too harsh, and between 1908 and 1912 many resettled in the Kootenays, in southeastern British Columbia. Most were peaceful but a small radical group, the Sons of Freedom, protested any government involvement in their lives. They took their children out of school, burned their own homes and barns, bombed government buildings, railway bridges and tracks, schools, transmission towers, pipelines and churches, and then, young and old alike, confounded other British Columbians by parading about in the nude. The impact and cost of the damages were enormous and even the CPR was forced to reduce the frequency of its train service through the area and restrict all travel to daylight hours. The federal government offered $25,000 rewards for information leading to convictions but the community was tight-knit and fearful, and the money was never claimed. While most of the havoc was created in the Kootenays, Doukhobors were skilled farm workers and many gravitated to the Okanagan to work in the orchards.

People rarely seemed to be the target of these attacks; bombs were usually set to go off when few were likely to be around. The threat to Princess Margaret’s safety seemed manageable. The Courier reported that Kelowna was “stiff with RCMP,” some of whom were wearing red serge while others were in plain clothes, though all carried guns. Roadblocks were set up to check all cars coming into town: guards rode the ferries and frogmen—scuba divers—scoured the bridge pontoons. (In spite of these precautions, two cars, each carrying three young Doukhobor men, would force their way into the royal procession in both Vernon and Kelowna. The RCMP intercepted, no explosives were found and the intruders were ordered to leave town.)

A mobile bomb factory was discovered less than a month later near an abandoned ranch at McKinley Landing, about eleven miles north of Kelowna. It had likely been there for some time, but in August 1958 police discovered ten powerful sticks of dynamite strewn in an arc over the hillside. Pieces of a badly damaged car were found along with the scattered remains of a twenty-year-old male. The car had likely been a temporary home for the two young men before the bomb they were working on exploded prematurely. The other man had managed to burrow under the wreckage and survive burns, lacerations, blindness and exposure for three days until he was discovered.

Doukhobor leaders soon ordered the remaining Freedomites to leave the Okanagan and return to the Kootenays. Though there were few other incidents in Kelowna, bombings, arson and the nude parades continued elsewhere in the province for several more years. Doukhobor parents eventually promised to send their children to school and the youngsters were released from an internment camp in New Denver. A fireproof jail was built at Agassiz to house the arsonists and many family members left the Kootenays to be near them. Though attempts were made to negotiate the group’s return to Russia or even to South America, nothing ever materialized. Their leaders were often seen as self-serving and manipulative, and followers paid a very heavy price for the very few, if any, benefits that came their way.

Of Unknown Origin

Though the Doukhobors had left the Okanagan, fire continued to be a recurring menace over the next several years. Most packinghouses were built with massive wooden beams that supported broad wooden floors where wooden fruit boxes were assembled and stored. Though the outside walls were corrugated iron or aluminum sheathing, they melted or collapsed during fires and did little to stop flames from spreading.

Glenmore’s Cascade Co-op fire in June 1960 was the first in what became a succession of packinghouse fires. The previous five or six years had seen few fires and while it was determined that this fire was caused by a dropped cigarette, the timing was curious. The plant was just gearing up for the apple harvest so boxes were stacked everywhere and all had been treated with fire-friendly wood preservative. Tanks of compressed ammonia had also been stored in the building and, as they exploded, hundreds of spectators gathered and then took to the surrounding hillsides for a better view. The sawdust insulation in the walls added more fuel to the flames. The nearest hydrant was five hundred yards away, and although a nearby irrigation ditch was dammed and the water pumped, residents were asked to turn off their sprinklers to boost the water pressure. Forest service fire-suppression crews arrived in case embers flew to the nearby hillsides.

In March of the following year, a raging inferno destroyed three KGE warehouses near downtown. Fire crews scrambled and managed to save the two adjoining buildings. It was a million-dollar blaze and firefighters arrived from Vernon, Rutland and Westbank to join Kelowna’s volunteer brigade. Along with the apple-grading equipment, over 100,000 cardboard boxes and several thousand cans of apple juice, apple pie filling and apricot concentrate stored in the building were also destroyed. The winds were light when a locomotive was brought to the area to help the firefighters: a cable was attached to the engine and wrapped around one of the covered walkways connecting the buildings to try to stop the fire from spreading. The first walkway tumbled to the ground but attempts to remove others were less successful as the cable kept breaking. The remaining three walkways became funnels for the flames spreading from one building to the next. Three- and four-storey walls collapsed, sending towers of flaming embers over the area. As the Courier noted, “cans of apple juice were popping merrily” from the heat.

City council had approved the purchase of the latest hydraulic ladder truck and a new pumper truck the night before the inferno. It wouldn’t arrive in town for another four and a half months, and the firemen had little alternative but to fight this fire with a fifty-five-foot extension ladder. It was so unwieldy that it took six men to manoeuvre it into place, and it had to be moved at least ten times during the evening, in order to be able to tackle the flames from every possible angle.

Two weeks later, the Courier headline declared “Fire Bug Feared” as a second fire destroyed another KGE warehouse and the neighbouring Occidental Fruit Company cold storage plant. It was later revealed that in the two weeks between the fires, charred newspapers had been discovered in another KGE plant but had been extinguished before the fire had spread. The RCMP and the provincial fire marshal decided this was no mere coincidence; this time losses exceeded $600,000. Fire crews came from Rutland, Westbank and Summerland and had to deal with dangling overhead power lines that serviced the city’s reservoir pump. If they were cut by the fire, the crews would lose all electricity, the pump would stop working and they would have no water to continue fighting the blaze. It was a potential disaster. Cyanide gases from burning fertilizer were a huge threat as was the risk of exploding ammonia storage tanks. An estimated four thousand people came to watch, spilling over the railway tracks as engineers shunted cars away from the flames, and then perched on the top of the cars for a better view. Along with the buildings, Sun-Rype lost about fifteen thousand cases of apricot concentrate, three thousand cases of pie filling, barrels of prune juice concentrate and thousands of cartons.

Vernon was also hit twice during the same time, as fire destroyed a large pile of empty boxes stacked on the railway platform adjacent to the packinghouse: only a cement wall had stopped the flames from destroying the building. Fruit industry buildings were also destroyed in Winfield and Summerland. Though there was no proof of arson, there were too many coincidences: there had been no packinghouse fires for years and now there were several; only the fruit industry was targeted; most fires occurred on Monday nights when there was little wind; and all were well established when discovered.

If these fires had been intentionally set, the fire bug took some time off… perhaps there was too much attention… but five months later, the Courier’s headline declared, “Occidental Struck Again in $350,000 Holocaust.” It was a further blow to the industry, the city and the company, which was still rebuilding its packing plant and the cold storage area destroyed just months before. The timing was even more suspicious as the apple harvest was only a few weeks away. The night watchman had made his rounds, gone into the compressor room for a few minutes, and emerged to find fires burning in several places. The older part of the dry wooden building covered a half a block and the explosions and fires seemed to light everywhere at once. The sawdust insulation burst into flame and crowds gathered again to watch as the flames shot two hundred feet into the air.

Again, no one could prove arson, but everyone speculated about the coincidences and then added a consistently full moon to the equation. Total losses exceeded $2 million; packing plants in the North Okanagan banded together, worked around the clock, and dealt with that year’s apple harvest. The Occidental’s tomato packing line moved to the Canadian Canners plant, processing continued and everyone struggled with increasing insurance rates. The whole community was on edge: other businesses increased their fire patrols and city council had no difficulty justifying the expensive new firefighting equipment they had just ordered. Arson or not, the packinghouses and warehouses had been built at a time when wood and sawdust were the only materials available: neither gave any protection against fire and sprinkler systems had not yet been introduced. Most of Kelowna’s early packinghouse history was destroyed in a very short span of time.

Growth, Regardless

Like many other farming communities after World War II, Kelowna needed room to grow. Still confined by its original boundaries, the city quickly ran out of land and surrounding orchards lured new housing developments and new industry. The health risks of malfunctioning septic systems and the risk of losing a growing tax base sent city council scrambling to gather adjacent neighbourhoods into its boundaries. Glenmore agreed to unincorporate in 1960 and its southern properties, including the Kelowna Golf Club and the cemetery, amalgamated with the city. The new Capri Shopping Centre and its “swank” new sixty-room hotel also became part of Kelowna. The surrounding residential development soon followed and Harvey Avenue, leading from the new Okanagan Lake Bridge, was straightened and redirected through the old Pridham orchard.

Not every neighbourhood wanted to become part of a greater Kelowna, however. Even promises of chlorinated water, sewer systems and better fire protection didn’t entice some. The residents of the old Guisachan farm threatened legal action if they were forced to amalgamate. It took four years of meetings between Kelowna and its neighbours, plus polling and referenda, before the next amalgamation took place. By the mid-1950s, when that happened, the city’s land base doubled and another 2,500 people pushed the population of Kelowna to 9,181. City council declared a five-year moratorium on further expansion… and then adjacent neighbourhoods began clamouring to be let in.

A few smaller boundary extensions occurred between 1960 and 1970, but when Orchard Park Shopping Centre opened in 1971, it was outside the city. The centre’s sewage had to be trucked across the lake to Westbank for disposal. When the businesses asked to have the boundaries extended so they could hook up to Kelowna’s sewage treatment facilities, residents objected. Ten percent of Kelowna’s voters signed a counter-petition, forced a referendum and stopped the boundary extension. The shopping centre’s neighbours didn’t want to lose their rural status but Orchard Park was so desperate the owners applied directly to the new NDP Minister of Municipal Affairs. He approved, Kelowna’s citizens weren’t asked and the rural neighbours were furious. Orchard Park Shopping Centre became part of Kelowna in March 1973 and arrangements were soon made for sewer and water lines to be extended to the complex.

Kelowna and the province had been discussing other boundary extensions but there was no indication what, when or if any changes might be made. Then, just seven weeks after Orchard Park became part of the city, the province announced that a new municipality was being formed: Kelowna’s boundaries would be dissolved and a new city would be formed to encompass the suburbs of Okanagan Mission, Rutland and Glenmore and all the land in between. The new city would also be called Kelowna but would now cover eighty-two square miles with about 51,000 residents. In 1971, the old city had been eight square miles with a population of just over 19,000. It was a quite a change.

Rutland was “shocked and disgusted” and declared democracy dead. Some saw the change as inevitable and knew that if asked, the citizens would never have agreed. Others thought it wise and necessary and the only way to deal with the water and sewage issues plaguing the area.

Farm, Anyone?

Many farmers felt they could make more money selling their land for houses than they could by farming it. Others were relying on their land to fund their retirement. The New Democratic Party had defeated Bennett’s Social Credit Party only a few months before but lost little time in bringing in legislation to preserve what it saw as the province’s fast-disappearing farmland. The NDP soon proposed Agriculture Land Use legislation, which restricted development on agricultural land.

Farmers were furious but so were real estate speculators: farmers didn’t think they should bear the brunt of preserving the province’s farmland, while speculators felt they should be able to develop anywhere. It was a curious partnership as orchardists and speculators both joined a raucous protest on the grounds of the legislature in Victoria. The NDP proposed the government purchase the development rights from the farmers with a lump sum payout. Though many agreed, the government then decided the option was too expensive and replaced it with a farm subsidy program. With many amendments, the Agriculture Land Reserve (ALR) legislation finally passed in April 1973.

Growers in the Okanagan were vocal and angry… the legislation was “dictatorial” and “totally unacceptable.” They divided into two camps: those who wanted to outright quit and those who wanted to continue but retain the right to dispose of their land any way they wished. Most were struggling financially and this was just “another nail in their coffin.” If the government needed their land, they should darn well pay for it. Some felt farm work was paying less than unemployment insurance or welfare, and if that was the case they’d stop repaying their loans. Then an elderly Benvoulin farmer reminded everyone that “future generations will curse you if you subdivide good farm land.” Some of the original ALR land was in frost pockets, or had poor soil, or steep hillsides, and sometimes the designation was lifted or changed. Agriculture still occupies almost half of Kelowna’s land base, and in spite of periodic challenges, few would argue today for the total removal of the ALR classification.

“Fruitleggers” began to multiply. Low returns had been plaguing orchardists for years and the battle over collective marketing was always simmering. The independents didn’t want to flaunt their opposition so they quietly stripped the back seats out of their cars, loaded them with boxes of fruit and smuggled the fruit out of the valley to Vancouver and Calgary. (There were few fruit stands or farmers’ markets at the time.) Fruit inspectors patrolled the highways but had little authority to seize the cargo. A bit of immunity went a long way and the independents became bolder and sent their fruit out of the Okanagan in convoys of pickup trucks. The RCMP was called in to stop them but didn’t want to get involved. The public were sympathetic, too, and it became a public relations nightmare the collective marketers couldn’t win. The long-standing disagreement between the fierce independents and those who felt collective marketing was the orchardists’ best option ended in a standoff.

The irrigation flumes, trestles and siphons that had criss-crossed the valley landscape for many years began vanishing in the 1960s. Over time, much had been replaced or rebuilt or improved upon but the systems were becoming increasingly expensive to maintain. The Agriculture and Rural Development Act provided funds and most of the irrigation went underground. While open ditches can still be found in Glenmore and in some parts of Okanagan Mission, most water is now carried to the orchards by pipe for spray irrigation.

We Need an Education

A few years after W.A.C. Bennett became premier, he embarked on a program to ensure BC had the educated workforce necessary for the province to thrive and flourish into the future. The decision showed great foresight and wisdom on the part of a leader who had not had the opportunity for such an education himself. The only opportunity in the province to get a higher education at the time was University of BC (UBC) in Vancouver. An announcement was made in 1960 to create a new BC Vocational School (soon to become the BC Institute of Technology—BCIT) and the University of Victoria, and Simon Fraser University was also under construction three years later. Located in the Lower Mainland and on Vancouver Island, they were beyond the reach of people who lived in the Interior and more remote communities. For many, the option of staying home to complete grade thirteen, first-year university, at their high school was a better choice while others chose to go directly to UBC after grade twelve.

Okanagan residents began lobbying for a junior college but had to settle for the BC Vocational School, which opened a Kelowna campus on KLO Road in September 1963. The school offered pre-employment and pre-apprenticeship training in a number of trades as well as practical nursing and commercial training. Prospective students were likely those who had left school early, wanted to be involved with apprenticeship programs or planned to move directly into the job market. Residents had aspirations beyond a technical school, however, and kept lobbying for a college. Old valley rivalries surfaced immediately and Vernon, Kelowna and Penticton all declared the college should be in their town. A committee of representatives from ten school districts, from Revelstoke to Osoyoos, was formed in 1964. An independent study was undertaken the following year to recommend curriculum, cost sharing and a location: sixty-five acres of the Westbank Indian Reserve overlooking Okanagan Lake. Not thinking there could be a problem, the committee signed a preliminary ninety-nine-year lease agreement. Early designs showed low white buildings nestled into the hillside with a stunning view across the lake… to Kelowna. Penticton withdrew support.

Vernon declared that the centre of the region had moved northward as a result of Penticton’s withdrawal and was adamant that the college should be built in their community. A referendum was held the following year to confirm everyone supported the consultant’s recommendations, including the campus across the lake from Kelowna. Only twelve percent of Vernon’s voters supported the recommendations and the proposal died. The committee remained undaunted and looked for ways to establish a college without having to go to referendum and rely on parochial voters.

Okanagan College became a reality in 1968, two years after the referendum. Since grade thirteen was paid for by the province, it was decided that the 165 students at Kelowna Senior Secondary, 72 at Salmon Arm Senior Secondary and 143 in Vernon would transfer to the college, with locations in each of the towns, and become the first class of the new institution’s two-year university transfer program. Full-time tuition was one hundred dollars per term per student. Everyone was suspicious and certain that it was only a matter of time before all programs would be consolidated in Kelowna. The committee knew another referendum wouldn’t survive the entrenched valley rivalries and the idea of a multi-campus college emerged.

Okanagan College in Kelowna started as two portables on the BC Vocational School’s KLO site in 1970: one was divided into classrooms while the other contained laboratories. They burned down a few months later. The following year, the BC Vocational School and Okanagan College in Kelowna become a single entity and staked out the KLO campus as their headquarters. Now both Vernon and Salmon Arm were convinced their programs would be closed so their funds could be diverted to enhancing the Kelowna campus. Penticton citizens decided they were losing out in spite of the turmoil and voted to join the Okanagan College system in 1974. Ten years after becoming a reality on paper, Okanagan College was still only offering the first year of a two-year diploma program and vocational students had to transfer to Vancouver and BCIT for their second year. Tenacity, vision and hard work prevailed but in the first ten years Okanagan College sometimes had little else going for it.

We All Must Adapt

Sun-Rype was utilizing most of the Okanagan Valley’s apple crop but when other juice makers began intruding into its traditional market, the company had to take a hard look at its product lines. Citrus juices had been a major competitor from the outset, but when staff recommended the company expand into these products, the members of the board, all apple growers, were horrified. They eventually agreed, however, and expanded the company’s product line, for the first time sourcing raw material from beyond the Okanagan.

As competition grew, Sun-Rype also had to rethink its relationship with the Summerland Experimental Farm. The federal research station and Sun-Rype had partnered on a number of new products: the station would develop the products, fine-tune the processing, and then make them available to whoever wished to go into commercial production. Sun-Rype had been developing its new products in partnership with the research centre since its inception but with the increasingly competitive marketplace, new products and unique processing methods became vitally important. Sun-Rype moved its product research in-house in the early 1960s.

Agriculture and the industries that supported it, including the sawmill, pretty well defined the community in the 1950s and 1960s. There was so little going on, in fact, that a federal program identified Kelowna as being one of Western Canada’s most vulnerable and underperforming areas. Money followed in hopes of getting private companies to move their operations to Kelowna. Some did, including White Star Trucks, Westmill Carpet and the American Can Company. Since Sun-Rype packed all its juices and pie fillings in cans at the time, and can costs were becoming an increasing part of the overhead, it explored the possibility of setting up its own manufacturing plant. Money was tight but with the federal incentive dollars in hand, it approached American Can about building a plant in Kelowna. The company had been shipping cans to Sun-Rype from its Vancouver plant for years and didn’t want to lose a good customer. American Can purchased land just north of the juice plant and connected the two operations with a conveyor line across the intervening road.

The arrangement lasted for a few years until the cans began to cost more than the juice they contained, and Sun-Rype again began searching for more cost-effective containers. Tetra Brik, a Swedish innovation, was being introduced to North America about this time; Sun-Rype revised its juicing process, tested the marketplace and devised new labels, then installed a Tetra Brik packing line in the Kelowna plant. The new containers were wildly successful and the company had to fall back on its canning line for a few months to keep up with the increasing demand. The American Can Company continued to supply other BC and Alberta customers from the Kelowna plant for a few more years before closing shop and consolidating operations back in Vancouver.

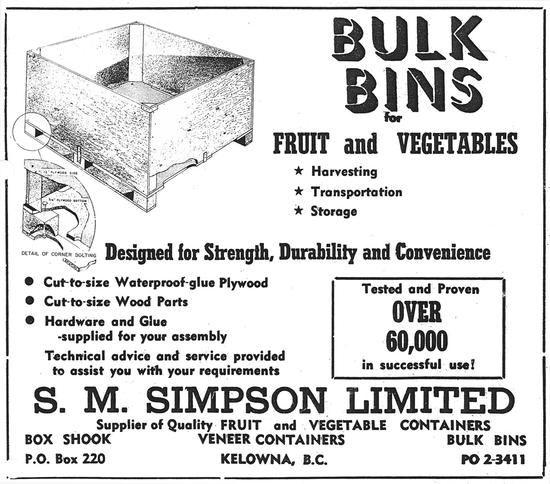

The fruit industry never fully returned to wooden boxes after the war. Experiments with various styles and combinations of wood and cardboard continued, adaptations were made and new materials introduced, and cardboard gradually pushed the traditional wooden boxes to the sidelines. The new packaging was a blow to the valley’s box makers and most simply closed shop and went onto other things.

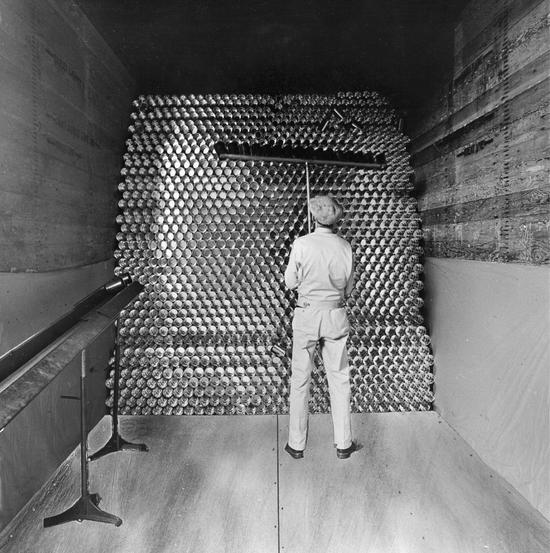

S.M. Simpson Ltd. was the exception. After considering a variety of options, the company announced the construction of a new plywood plant at its Manhattan Beach location. The land was still plagued by high water tables but layers of sawdust, slabs and shavings overlaid with gravel had made it workable. The new plywood plant created more challenges as over 3,500 pilings were driven twenty to forty feet into the ground, which left four feet above ground to support the floor. Premier Bennett officially opened S & K Plywood in May 1957 during one of his visits to inspect the progress on the new Okanagan Lake Bridge. The unsanded spruce plywood the plant produced was used by the construction business until an opportunity appeared that enabled the company to get back into the fruit business.

When staff from the Summerland Research Station visited New Zealand in 1954, they discovered a shallow apple bin made from lumber, linoleum and war surplus bomber tires that was being used in the orchards. It was efficient, the apples required less handling and it required less manpower. They were quickly convinced the system, with some adaptations, could work in the Okanagan. An industry committee soon agreed on the dimensions for the new bulk bin, which held the equivalent of twenty-five boxes of apples and only required orchardists to add a fork to the front of their tractors to lift the bins onto the truck deck. Once the apples were delivered to the packinghouse, the bins could be returned to the orchard and used again, and again.

It didn’t take long for Simpson’s to start building the bins from plywood. When the apples were bruising as they were dumped onto the packinghouse conveyor belt, a system was devised to submerge the bins in water; the apples would float out and water currents would carry them to conveyor belts for grading and packing. S.M. Simpson Ltd. was awarded a patent for the new bin in 1960, as growers from Osoyoos to Vernon and then Washington state converted to the new system.

An export market soon developed, when Simpson’s established a production facility in England. The bins were initially sent from Kelowna unassembled, but when a strike at the Kelowna mill shut off supplies, the company sent sheets of plywood to be cut and assembled on site. The English subsidiary supplied seventy percent of the United Kingdom market by 1967. The bins moved on to Europe as well, where they were adapted to meet other countries’ needs, and then on to South Africa and South America.

Bulk bins have been an integral part of the Okanagan fruit business for half a century now and the apple boxes they replaced are collectors’ items. The bins have been adapted for many other products: smaller sizes are used for soft fruits, grapes, vegetables, frozen food, fish and seeds. Manufacturing companies use the bins for shipping parts; others use them for storage or even coffins. Some are now plastic. From the germ of an idea that was transplanted from one side of the world to the other, the bulk orchard containers that were reconfigured and fine-tuned in Kelowna have now spread around the world.

In the never-ending cycle of boom and bust, S.M. Simpson Ltd. was bought by the American multinational Crown Zellerbach (CZ) in 1965. In the intervening years several more companies have owned the Kelowna mill though they too are no longer in business. In 2004 Tolko Industries Ltd., a Canadian-owned specialty forest company based in Vernon, bought the original Manhattan Beach sawmill and plywood plant. Its products have changed, as has the plant itself, which is now surrounded by a much-changed and expanded city. In spite of occasional speculation about its demise, the sawmill built by Stan Simpson in the early 1930s, the valley’s largest year-round employer at the time, continues to be one of Kelowna’s major businesses.

Shortly before his death in 1959, the City of Kelowna honoured Stanley M. Simpson, the mill’s founder, by awarding him the Freedom of the City for his contribution to his adopted community.

Finally: Okanagan Lake Bridge

Many early residents thought the idea of a bridge across Okanagan Lake was preposterous: it was too great a distance and would cost far too much. Yet as more people moved to the valley and tourism became a reality, the ferries were seen as an irritant and an obstacle to the free flow of both cars and goods. With the arrival of the Cold War in the 1950s and related talk of World War III, a bridge across Okanagan Lake was seen as a “missing link” in the free flow of traffic between California and the Alaska Highway. Other valley communities were canvassed to see if they supported the idea. The usual rivalries came to the fore and Penticton’s mayor never did come on side. Naramata residents were furious at the prospect of their long-hoped-for road along the east side of the lake being usurped by a bridge. The premier assured them their road would be built… when increased traffic warranted it.

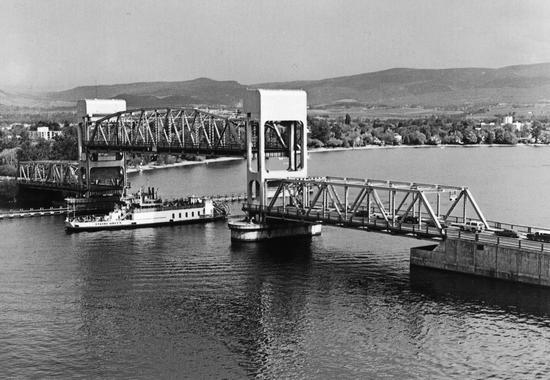

With the arrival of Social Credit and their mandate to get BC moving, bridges were already being built in other parts of the province. It took awhile to convince the government the Okanagan Valley really needed a bridge… or perhaps the premier didn’t want to be seen favouring his home town. Though locals had been advocating for free ferry passage for some time, they didn’t seem averse to a toll bridge. While a previous government had toyed with the idea of a bridge and had gone so far as to design a twin-towered suspension bridge rivalling Vancouver’s Lions Gate, there was no money to build it. When Social Credit came to power, they redesigned the bridge into a causeway, pontoon and lift span alternative. Tenders were called in December 1955 for the less glamorous and less expensive bridge, which was also more suited to the shifting sand on the bottom of Okanagan Lake. Everyone was certain the new Okanagan Lake Bridge was the solution to the traffic problems that had plagued the valley from the time the first settlers arrived.

Most of the equipment needed to build the bridge was brought by train from Vancouver: a concrete plant, a pile driver, the prefabricated steelwork and a tug. A construction camp was set up on the old railway lands (now Waterfront Park); a graving dock was dredged and fitted with eighteen-foot timber doors for the construction of twenty-four concrete pontoons. Each pontoon weighed seventy tons, at two hundred feet long and fifty feet wide. The pontoons were attached to the road deck with steel cables that had been embedded twenty-five to thirty-five feet into the lake bottom. The pontoons were floated to the bridge site, earthen causeways built—1,400 feet from the west and 300 feet from the east. City Park had to be reconfigured and many were certain the park would be ruined. Japanese Canadians donated ornamental cherry trees, an addition was made to the existing grandstand and a new park entrance and paved roads convinced the skeptics the park would survive. An operator sat in the bridge control room halfway up the east tower to raise the 260 foot vertical span and give 60 feet of vertical clearance to the barges and rigid-masted sailboats.

People in Kelowna were almost as excited about Princess Margaret coming to town as they were about the bridge. This was the princess’s first trip to Canada; she was twenty-seven, beautiful and very royal. The front page of the Daily Courier’s sixty-page Souvenir Bridge Edition featured Margaret on the top half with a photo of the new bridge relegated to the lower half. A temporary Government House was again created in Okanagan Mission: it was panelled throughout with BC cedar; all rooms overlooked the lake; the living room had turquoise walls with a dark-beamed ceiling and a coffee table surfaced in white tile. The sun-dappled lawn went down to a wharf decorated with centennial bunting (this was also BC’s one hundredth anniversary), and “the water was clear, with a bottom of sand and gravel that the Princess need never touch.” Every minute detail was revealed. The power in the house went out at one point, sending the resident RCMP officers into panic mode until they realized the extra communications equipment installed for the occasion had overloaded the circuits.

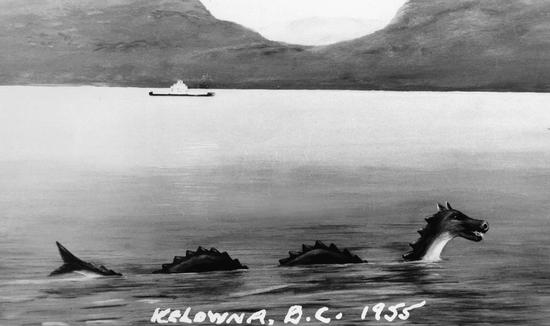

Kelowna gave Princess Margaret an “ardent and zealous welcome.” Over five thousand schoolchildren packed into the Aquatic’s Ogopogo Stadium the night the princess arrived and alighted from an amphibious Mallard aircraft belonging to Pacific Western Airlines. Premier Bennett greeted her, and the crowd broke into a rousing rendition of “God Save the Queen” and those who had the privilege of meeting her—and there were many—“felt momentarily transported to a wonderland.” The welcome lasted twenty minutes. The local rumour mill was working well as word spread that Captain Peter Townsend, the princess’s unsuitable love interest at the time, had quietly arrived in town to meet her.

Businesses along the royal travel route were encouraged to decorate their storefronts and citizens were told to display flags. All stores were closed during the opening ceremonies, though restaurants and women’s church groups sold box lunches for spectators to take to the park. The bridge opened for traffic an hour and a half after the official ceremony but the toll booths didn’t open until midnight the following day. The MV Lloyd-Jones, the most recent addition to the Okanagan ferry fleet, sailed past the new bridge in tribute on Saturday at four p.m. with 190 dignitaries on board. The captain sounded a salute and the lift span operator responded. It was the end of an era and the long, proud and often fractious history of the Okanagan Lake ferries.

Those who remember living with the ferries have many stories about racing down the west side hill, with car horn blaring, in hopes the captain would hold the last sailing of the night for arrival. Others remember waiting for hours on holiday weekends for the next ferry only to miss getting on board by one car. Sometimes the ferries transported hazardous material but that was usually late at night and no one else was allowed on board. Other times sheep filled the entire deck, on the way to their summer pasture, and then no one else wanted to be on board. There was also the occasional well-orchestrated getaway that left the unsuspecting stranded on one side or the other. There were many efforts to keep a channel open when the lake froze but when that wasn’t possible, sailings were cancelled. The ferries remain a colourful and charming part of Kelowna’s history and speak of a slower time—which was, in the end, what people complained about most.

A BC Toll Highways and Bridges Authority had been created by the Bennett government to raise money to pay for the construction of the province’s new bridges and highways. The debt was to be paid off by the tolls collected on Okanagan Lake Bridge, among others. A single trip for most vehicles was fifty cents a crossing or, for commuters, fifteen trips a week for $1.50. Trucks paid from seventy-five cents to $2.00, depending on the size. The tolls remained in place for five years until Premier Bennett suddenly announced their removal on April 1, 1963. The only official ceremony marking the end of the tolls was held in Kelowna where the mayor announced, apparently with a straight face, that “there are no politics involved in this occasion.” Bridge decorations soon arrived from Victoria to mark the non-event. Traffic was halted from both the east and the west so senior civic officials from all over the valley could join the premier on the bridge for the brief ceremony. A no-host luncheon followed with Kelowna’s mayor encouraging every valley community to attend “to show their appreciation to Premier Bennett for what has turned out to be a major economic factor in the present health of the Okanagan.”

One Disaster After Another

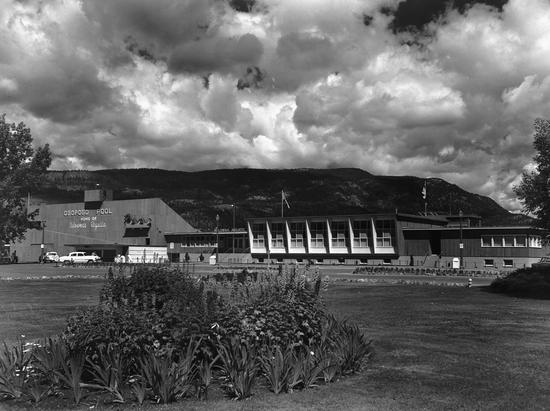

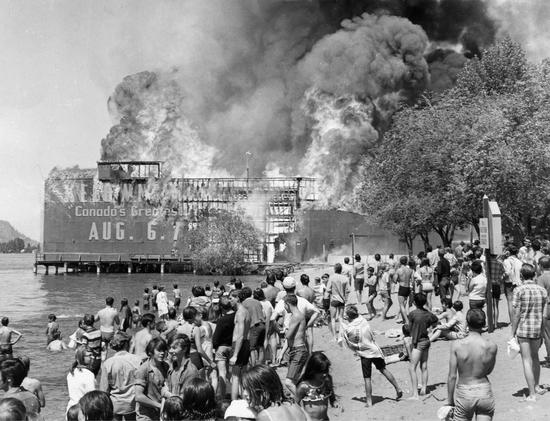

The Kelowna International Regatta continued, though the organizing committee sometimes struggled to maintain the momentum and attract headline acts for the evening shows while keeping it a family event. However, all of the things that could possibly go wrong came together in 1969. Two young boys were seen playing with matches under the 4,400-seat wooden Ogopogo Stadium in mid-June. Soon flames spread up and along the seats, engulfing the pavilion’s restaurant—including the plate of sandwiches ready for an afternoon event—the dance and banquet hall, the change rooms and the boat storage. Staff raced through the building to make sure no one was inside and then headed underneath and tossed racing shells, oars and Regatta night show decorations into the lake.

The Aquatic’s facilities were the most widely used in the city and the loss was not only a blow to “Canada’s Greatest Water Show” but also to the generations of Kelowna residents whose lives centred around City Park and the Aquatic. Children had taken swimming lessons and then spent most of their summers in Ogopogo Pool; they had participated in weekly Aquacades, and competed and performed in the Regatta. Some had gone on to become Lady of the Lake candidates while others earned their Red Cross Bronze Medallions and became lifeguards. Many of their parents had done the same and then danced in the ballroom and attended community banquets at the only suitable facility in town. The Aquatic fire ended an era that had shaped the lives and friendships of generations of residents and visitors alike.

The community rallied and nothing was cancelled for that year’s Regatta. Tommy Hunter headlined the night shows for spectators who sat on temporary bleachers and gathered to watch the manoeuvres of the crack US Navy Blue Angels precision flying team. The team had managed the short airport runway but found the mountains made their formations a bit tighter than usual, and held a practice in the afternoon to make any last minute adjustments. One pilot found himself a little higher and a little behind in one of their formations and cut in his afterburner to catch up. The plane exceeded the speed of sound, though only momentarily, and blew out seventy-five percent of the windows in an eight-block area of downtown. Six people were injured, though none seriously. Plywood was slapped over the gaping holes in the office and shop windows and the Regatta Parade carried on as scheduled a few hours later. NATO paid for the repairs.

The third in the Regatta’s trio of disasters got very little press—perhaps the event organizers felt jinxed and didn’t want to talk about it. The Kamloops Sky Diving Club had been performing during the Regatta when the parachute of one of their divers became tangled, and he fell to his death. It was a year of disasters at Kelowna’s premier summer event and local newspapers were reluctant to report more bad news. In fact, it was 24-year-old Ken Ferrier, president of the Kamloops club, who lost his life at that calamitous regatta.

Kelowna was growing and by the late 1960s had already recognized the need for more recreation opportunities. A massive report highlighting the need for an indoor pool, a community centre, a seniors’ building and acres of playing fields had been released only a month before the Aquatic fire. It lurked in the background as the community struggled to deal with the loss of their Aquatic Centre and discussed what to do with the $300,000 insurance settlement. Those who wanted to rebuild also wanted a huge swimming pool, a much larger yet also portable grandstand, more restaurants and a dance floor. Others wanted it to become the town’s convention centre. Some wanted the new facility to be in City Park; others didn’t. It took many many meetings and endless discussions before the decision was made to add the Aquatic insurance dollars to other municipal funds and create the multipurpose midtown Parkinson Recreation Centre. The centre was named after Dick Parkinson, “Mr. Regatta” to many and later the mayor, in recognition of his contributions to the community. The decision remains contentious among those who lived in Kelowna at the time and grew up at the Aquatic. Yet the rec centre’s indoor pools, various multipurpose rooms and outdoor playing fields have evolved over the intervening years and are still much used.

Gradually, the Regatta drifted away from its focus on the lake and its traditional activities were replaced with soccer tournaments, wrist-wrestling championships and a lumberjack show. A craft show was held in the arena, which was later transformed into a casino. An agricultural show was held in City Park along with a Bavarian beer garden; a volleyball tournament was followed by a bathing suit contest and a bathtub race to Penticton. The new Regatta paid less attention to the water and lost some of its family focus. Residents complained that City Park was overused, as what little remained of the Ogopogo Pool began falling apart. For a few years, an Aquatic Exhibition Park was created at the north end of town and though the demise of the Kelowna International Regatta was likely underway, few would have admitted it at the time.

Kelowna: A Four Season Playground

Kelowna’s new logo with its “Four Season Playground” tagline was introduced to the Kelowna Chamber of Commerce at a dinner meeting in 1964. Most of those attending were mystified by the four blank quarters of the circle until springtime golfers filled one quarter, swimmers and boats on a blue-green lake another, grapes and a travelling car another, and finally skiers in the fourth. The logo was the symbol for the 1964 visitor promotion program and members were urged to add it to their stationery, bumper stickers and brochures, and have gas station attendants and waitresses wear it as part of their uniform. A small pocket-sized card was prepared so those who were asked about the logo would have the information handy. It was hoped that those wearing the logo would feel they were officially representing Kelowna and would reap the benefits that would naturally follow from being more polite. While the logo has been abandoned and the tagline has become “Kelowna—Ripe with Surprises,” the city continues to portray itself as a vibrant and inviting four-seasons playground.

The Okanagan’s Very Own

The Courier headline proclaimed “Kelowna opened a major door to the Electronic Age” when “The Okanagan’s Very Own” CHBC-TV was launched in 1957, only five years after Canadian television was launched in Montreal. Its creation came about as the result of a unique collaboration between the owners of the valley’s three radio stations—the Browne family from Kelowna’s CKOV, Roy Chapman from Penticton’s CKOK and Messrs. Pit and Peters from Vernon’s CJIB. The colleagues put up a quarter of a million dollars and created the Okanagan Valley Television Company. Engineers came from RCA Montreal to scout the surrounding mountaintops for the best line-of-sight signal; the production studio, which needed to be near the main transmitter, was created out of the renovated Smith Garage in downtown Kelowna. Roy Chapman became the managing director and hired engineers, program directors, promotion managers and on-air personalities. Several pages of the Courier featured the station’s launch, stating the channel would be the vehicle for a “great visual and aural exchange of ideas, both nationally and internationally and give Valley citizens new dimensions and stature.” The schedule was guaranteed to entertain and educate viewers, connecting them to a bigger world. Ed Sullivan, Douglas Fairbanks Presents, Dragnet, I Love Lucy, Captain Kangaroo and The Lone Ranger were regulars, and when all else failed the station’s camera was trained on its fish tank—at least something was moving on the screen.

The Courier was full of stories about how those pictures got into that box, what style of cabinet would be most appropriate for a television—sophisticated modern would be jarring in the Victorian living room—and new buyers should not worry about keeping up with their neighbours. Stories also warned that the biggest set might not be the most suitable for your room, and you shouldn’t stare at the screen for long periods of time. Most importantly, the correct viewing distance from the screen was calculated as ten times the width of your screen: fourteen feet away from a seventeen-inch screen and eighteen feet away from a twenty-one-inch screen. “Baby Sitter Problem? Get a TV.” The newspaper was full of advice; advertising filled its pages as every store in town seemed to be selling TV sets and the Courier’s new TV program guide became a sought-after weekly feature.

Okanagan Lake Bridge’s official opening provided the first opportunity for live TV coverage of a major outdoor event. With no mobile equipment, the studio, control room and microwave receiver had to be dismantled and reassembled at the east end of the bridge. When the hour and a half broadcast was over, the equipment was disassembled and returned to the main studio.

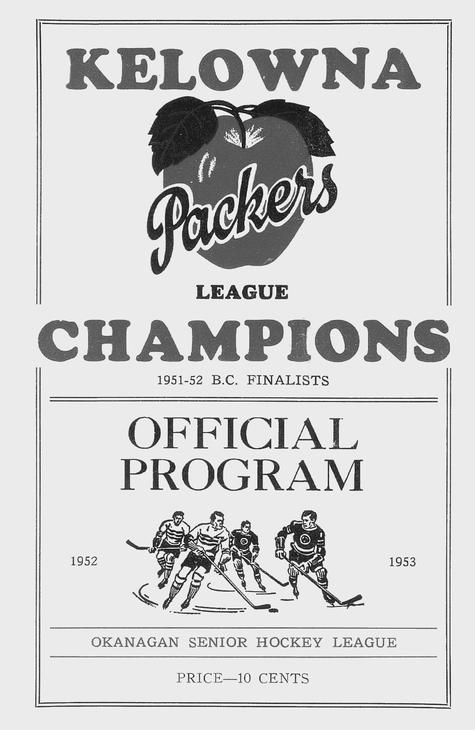

Everyone’s a “Packer Backer”

Everyone in town supported the Kelowna Packers during the hockey-mad years of the early 1950s. Cavalcades of fans followed the team to each game as they played the Kamloops Elks, the Vernon Canadians, and the Penticton Vees in the Okanagan Senior Hockey League. Rivalries were physical and noisy and there was rarely an empty seat at Memorial Arena: fans “literally hung from the rafters.” The Penticton Vees won the national Allan Cup in 1954 and represented Canada in the World Amateur Hockey Championships in West Germany the following year. Their five-nothing defeat of the Russians vaulted them into legendary status.

The Kelowna Packers won their league championship in 1958 as well as the subsequent quarter-finals and semifinals on the way to the Allan Cup showdown with the Belleville (Ontario) Macs. Kelowna lost in a final “titanic seventh game struggle” but earned themselves a trip to Sweden and Russia as a result. This was during the height of the Cold War and the Packers were the first Western sports team to be invited behind the Iron Curtain. The strength and speed of the Russian teams were legendary and no one gave the Packers a chance of winning even one game. When they lost the first game against Sweden, Kelowna fans sent a huge telegram wishing them well: they won the next two games and the fourth game was cancelled without explanation.

The team flew on to Moscow, arrived at the Sports Palace and faced a highly partisan crowd. Kelowna lost the first game against the Wings of Soviet, then tied the second. When they tied the third game against the Moscow Dynamos, Kelowna fans danced on Bernard Avenue. Then the Packers started to win: four-three in the next game and then they trounced the vaunted Russian team five-one in the final game. The Russian players were gracious and said, “the Canadians are magnificent hockey players.” Kelowna held a giant civic reception and banquet for the Packers when they returned home.

A somewhat different picture emerged when the returning players told their stories. They had considerable apprehension about going behind the Iron Curtain and team members recalled being constantly afraid. Soldiers had silently boarded their plane when it arrived in Moscow, they were followed everywhere and they even felt compelled to leave the lights on in their hotel rooms at night. Some said that aside from winning, the best part of the trip was leaving—“we were only there nine days but it seemed like a month.” There was no traffic on streets so wide you could have landed an airplane on them, there were no neon signs, everything was concrete, so bleak, so poor, and everyone dressed the same—in black. The only good food they ate was at the Canadian Embassy. No one was in a hurry to return to Russia, though all agreed it was an experience they would never forget.

Kelowna Moves On

These were twenty transitional years for Kelowna. It was no longer a small town—it had become the fifth largest city in the province—but neither was it very big. The Hope–Princeton Highway brought people to the area from Vancouver and the new Okanagan Lake Bridge made it easier to move within the valley. The Rogers Pass became part of the Trans-Canada Highway in 1962 and access from the east was easier. It still wasn’t a direct route to the Okanagan, but it was a vast improvement over the gravel Big Bend Highway that had previously been the only Canadian alternative.

The Kelowna Airport runway was extended and paved, navigation lights were added on the field and surrounding mountaintops and Canadian Pacific Airlines scheduled twice-daily service. The two-hour trip to Vancouver included a brief stopover in Penticton. With a one-way ticket costing eighteen dollars, businessmen were encouraged to fly to Vancouver and return home the same day.

New highways and bridges, more cars and trucks, and improved air service soon pushed train service to the margins. By 1961, the CN passenger train was replaced by a Railiner, a self-propelled diesel passenger car. This lasted for about two years until CN put their passenger train back into service in hopes of attracting more traffic. It took only a few months for them to realize that times had truly changed. In October 1963 the passenger train was replaced by a chartered bus, which left Kelowna at 8:30 p.m. and made various stops on its way to Kamloops, where passengers transferred to the transcontinental about midnight. Kelowna’s love affair with passenger rail travel had lasted thirty-eight short years. CP ended their barge service on Okanagan Lake in May 1972 and CN followed a year later. Soon, their tracks were torn up, the wharf demolished and their tugs were sold. Trucks had become the carrier of choice and the storied era of lake travel was over.

The ALR, coupled with its expanded boundaries, profoundly impacted the way Kelowna evolved over the next few years, as pastures, orchards and vineyards became part of the community. Residents who otherwise had little to do with farming began looking forward to spring blossoms and fall harvests as they settled comfortably into their midst.

The neighbouring communities of Okanagan Mission, Rutland and Glenmore, and the smaller communities of East Kelowna, Ellison and Benvoulin, initially feared they would lose their unique identities when they became part of Kelowna. But it wasn’t long before residents realized they could retain the character and feeling that defined them when the areas were first settled.