Chapter 8: Setting up Shop

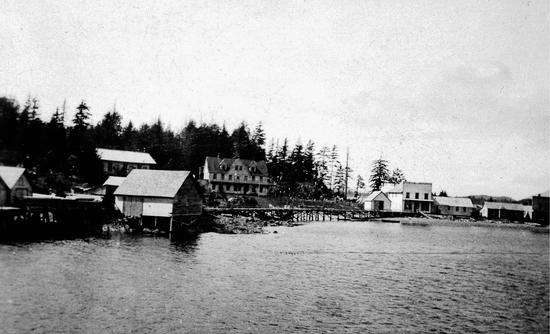

Of all trading posts on Vancouver Island’s west coast, the one at Clayoquot on Stubbs Island emerged as the most significant. First established in 1854, and important for its central location on the coast, Clayoquot offered protected anchorage for trading schooners, an easy landing for canoes on the sandy beach on the lee side of the island, and rich potential for trade with nearby First Nations. Its early years saw only sporadic activity, with periods of seasonal trading followed by long stretches when not much occurred, but as the dogfish oil trade and later the fur seal industry gathered momentum, Clayoquot drew increasing business. By the mid–1890s, it had become a vital centre for commerce and communication on the coast.

Back in 1854, William Banfield set up this pioneer trading post in partnership with Captain Peter Francis and Thomas Laughton. During the mid-1850s, Banfield and Francis came and went at Clayoquot in their trading vessel Jibo, doing most of their trading in the late summer and early fall, when local people traded their dogfish oil and a variety of furs, including seal skins. Like other early trading posts, the buildings at Clayoquot consisted of little more than storage sheds with crude living quarters attached. At the end of the season, the traders would empty the rudimentary buildings, load their furs and barrels of oil onto their schooners, and sail to Victoria to sell their stock to the Hudson’s Bay Company. The rest of the year the buildings on Stubbs Island stood empty, facing blankly over the water toward the site of present-day Tofino on the Esowista Peninsula. No one lived there; the nearest settlement to Clayoquot lay at the Tla-o-qui-aht village of Opitsaht, on Meares Island.

Banfield and his partners set up other trading posts on the west coast at about the same time as the one at Clayoquot. Thomas Laughton ran one to the south, at Port San Juan, near present-day Port Renfrew, and the ill-fated Maltese trader Barney had charge of the Kyuquot trading post. In 1859, Banfield left his partnership with Francis and Laughton and bought land at the head of Barkley Sound from the Huu-ay-ahts for the price of several blankets, some beans and molasses. He extensively explored the area around Barkley Sound and up the Alberni Canal, as well as Clayoquot Sound. In 1860, in his capacity as government agent, Banfield assisted Captain Edward Stamp when he established the first west coast sawmill at Alberni.

Banfield was the first settler in Barkley Sound, and his name still endures there. The town of Bamfield—despite the spelling corruption—is named for him, and also Banfield Creek. Such a legacy would have dismayed Banfield. In 1858, having observed how the explorers, traders, and government mapmakers named the features of the coast after themselves and their cohort, he wrote protestingly, “However much the old navigators’ names are entitled to respect, good taste would lead us at the present day to adopt the Indian names [which] in most instances are much prettier, many of them having a natural beauty of sound…Great Britain’s Colonies have enough Royal names, noble names, and titles of our grandfathers and grandmothers and birthplace names…let us differ a little from our neighbors of Washington Territory, with their Websters, Pierces, Madisons and Monroes and Jeffersons attached to every little group of log shanties that rises out of the bush.” Any quick glance at a map of the coast reveals how Banfield’s words went unheeded.

A keen observer of coastal geography and resources, Banfield extolled the rich potential of the west coast of Vancouver Island in a series of articles for the Daily Victoria Gazette in 1858, focusing particularly on Barkley Sound and the Alberni Canal, but also describing a trip to Clayoquot Sound. Noting the Tla-o-qui-aht to be “the most intelligent tribe I have met with,” he wrote of their territory as “the great canoe mart of the west coast…canoes varying from three to 10 to 60 feet [1 to 3 to 18.75 metres] in length, of the most accurate workmanship and perfect design.” Banfield reserved his best descriptive skills for a Tla-o-qui-aht potato feast he attended. “Immense quantities of potatoes are purchased every year by this tribe from white traders and the Macaws [Makahs],” he wrote. “I have seen 70 bushels of potatoes cooked at once, in two piles on hot stones. They eat whale oil in quantities with potatoes. At these feasts, probably 200 or 300 guests are invited. The females are never asked. Much decorum prevails and positive urbanity is shown to every guest, rich or poor.” He continued, describing the strictly observed rituals of cleanliness and eating, and, following the meal, the recitation from memory, by the chief’s children, of celebrated stories and speeches.

Banfield’s conviction that settlers would soon venture to the west coast proved correct. Early in 1860 he reported to Governor Douglas that Captain Charles Stuart was building a house and planning to settle in the Ucluelet area, the first European to do so. A bay in Ucluelet Inlet bears Stuart’s name. He had joined the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1842, serving on many of the company’s ships until appointed officer-in-charge at Nanaimo in 1855. Later discharged for chronic drunkenness, Stuart briefly operated a trading post at Ucluelet but did not remain there long. He died in 1863. Captain Peter Francis succeeded Stuart in 1862 at the Ucluelet trading post, which he ran for several years. Francis Island in Ucluelet Inlet bears his name.

In 1869 Captain William Spring opened a trading post at Spring Cove in Barkley Sound, on land acquired from the local tribe for a barrel of molasses. By this time the partnership of Spring and Hugh McKay dominated trade on the west coast, with their fleet of schooners and trading posts at Kyuquot, Clayoquot, Spring Cove, Port San Juan, and Ucluelet. Peter Francis continued trading on the coast for years, often working with or for Spring and McKay, operating their schooners Alert and Surprise, and running their trading posts. At various times Francis took charge of trading posts ranging from Port San Juan to Spring Cove or Clayoquot, where he likely used Banfield’s original buildings as his store and living quarters.

Francis’s earliest experience as a trader at Clayoquot occurred in June 1861, working with Charles Edward Barrett-Lennard and Napoleon Fitzstubbs, the two English adventurers who briefly dabbled in west coast trade after circumnavigating Vancouver Island in 1860 in their yacht Templar. For a short while, Templar served the Clayoquot trading station, but Barrett-Lennard soon found trading with the Nuu-chah-nulth not to his liking. Safely back in England in 1862, he wrote that he generally found every Indigenous person “treacherous and deceitful…and more or less a thief at heart.” Probably the locals got the better of him in trade.

A chart dated 1861, drawn up by Royal Navy surveyor Captain George Henry Richards, notes the presence of the store at Clayoquot and also pinpoints another to the north, at Ahousaht. This “store” at Ahousat probably served as little more than an occasional trading facility, operated by Spring and McKay, using their schooner Surprise to visit it. Puzzlingly, on this map the letters “PO” appear beside the word “store” at both Clayoquot and Ahousaht, indicating a post office. However, in 1861 only two post offices existed on Vancouver Island, at Nanaimo and Victoria. This “PO” notation may simply mean that, on occasion, when a trader showed up, mail might be on board for any fellow trader in the vicinity, or could be taken out from there; such postal service would have been chancy and unofficial.

The detailed surveys carried out by Captain Richards and his crew of over a hundred men created the baseline of information for nautical charts still in use today. Between 1857 and 1862 they charted the entire coastline around Vancouver Island, for the final two years travelling aboard the imposingly large, 810-ton HMS Hecate. Richards’s officers included Lieutenant Daniel Pender, Edward Parker Bedwell, John Thomas Gowlland, George Alexander Browning and Edward Blunden, all of whose names appear on BC coastal maps. They came prepared to trade with local people for food and information about the coast, bearing goods such as blankets, molasses, rice, flannel, and blue serge, as well as looking glasses, beads, soap, and tobacco. Captain Richards had been on the west coast before, in 1838–39, when he served aboard the British Navy’s survey vessel HMS Sulphur, from which Sulphur Passage in Clayoquot Sound takes its name. He had met Chief Maquinna at Nootka, and on this 1861 voyage his “old friend Chief Maquinna” greeted him again, “dressed in a blue frock coat with 3 rows of buttons one row American Eagles the other Royal Marines. A pair of black cloth trousers and over all a long black beaver hat.”

In the early 1860s, James Douglas Warren, with his sloop Thornton, began trading on the West Coast. By 1864 Warren had taken charge of the trading post at Clayoquot, and within a few years, following Spring’s example, Thornton was carrying Tla-o-qui-aht hunters out to the sealing grounds in search of fur seals. In 1871, Warren entered into a partnership with Joseph and Jacob Boscowitz, who went on to become the most successful fur buyers in Victoria. Four years later, Warren became the first person to pre-empt land in Clayoquot Sound. He applied to purchase a large portion of Stubbs Island in 1875, paying $62.50 for “Section One,” the northern 25 hectares of the island.

Years later, when settler John Grice arrived to stay permanently in the area, he noted Warren’s early pre-emption: “I remember being at the Lands Office in 1891 and found his name registered for Stubbs Island.” Grice also stated that Captain Hugh McKay had set up a station for the sealing trade where Tofino now stands, adding that McKay “evidently was greatly respected by the Indians, as I learned from Old Indians who had been in his Employ.” So by the late 1860s, and certainly through the 1870s, when Warren was at Clayoquot and McKay based at the site of present-day Tofino, the local trading scene gained momentum.

Without question, as trade picked up on the coast, more and more alcohol began to be introduced to the Nuu-chah-nulth. As Captain George Henry Richards observed:

Richards further commented that “it is not difficult to see which way [the Indigenous] morals are tending—as their communications with ourselves increase.” In a letter to his commanding officer, Rear Admiral Robert Baynes, Richards clearly held European traders on the coast responsible for many wrongs, particularly for trafficking in liquor and for demanding and sometimes seizing local women. When conflicts arose, he firmly stated, “My opinion is that the Natives in most instances are the oppressed and injured parties.” In his own travels on the coast, Richards experienced nothing but helpful co-operation from the local people.

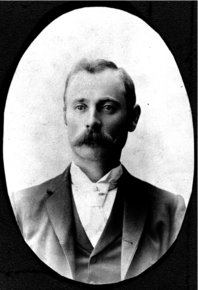

In 1874, Captain Warren introduced one of Clayoquot Sound’s most memorable characters to the area. He hired Frederick Christian Thornberg to run his Clayoquot trading post, making Thornberg the first year-round European resident of the Tofino area. Over the next three decades, Thornberg became a notable chronicler of events in Clayoquot Sound. Unpredictable, quick-tempered, and mentally unstable, Thornberg wrote volubly about the west coast and his own experiences. His many long, rambling letters and his brief personal memoirs provide a wealth of detail about life in the Sound. He wrote about schooners, storekeepers, sealing captains, Indigenous people, settlers and missionaries, never hesitating to complain, to find fault, or to accuse others—never mind who—of being wrong. Yet even though Thornberg’s writings sometimes degenerate into personal tirades, his colourful descriptions, filled with wild misspellings and abbreviations, bring a whole era alive in a way no other documents can match.

Born at Stege, on Mooen Island, Denmark, on December 31, 1841, Thornberg went to sea aged fifteen. After serving six years before the mast, he arrived in Esquimalt on February 22, 1862, aboard the Black Knight, carrying a cargo of Welsh coal round Cape Horn for Royal Navy ships based on the West Coast. Luckily for Thornberg, he jumped ship in Victoria; on its homeward journey, Black Knight, loaded with ship’s spars, foundered and disappeared. At Victoria, Thornberg landed a job as a servant for the Honourable David Cameron, Chief Justice of Vancouver Island. He married Cecily Harthylia, a Songhees woman, in June 1867; she bore him three children. “We had one child live [Johanne],” Thornberg related in his memoirs. “Second Child was O.K. but orders came to have Children vacinadet [vaccinated] and she got sick and died. Third Child was still born in Victoria.” Thornberg later tended sheep in the San Juan Islands for some time, and eventually his experience as a seaman and his facility with languages brought him to the attention of west coast traders. Captain Spring signed him on to the schooner Favorite, and Thornberg found himself sailing up and down the outer coast of Vancouver Island. In 1874 Captain Warren engaged him to work at the Clayoquot trading post.

When Thornberg and his family arrived at Clayoquot that year, Peter Francis then operated the trading post at Spring Cove in Ucluelet, Andrew Laing had charge of a trading post at Dodger’s Cove in Barkley Sound, and Neils Moos ran Spring and McKay’s store at Port San Juan. These four traders constituted the only Europeans then living on the west coast of Vancouver Island northwest of Juan de Fuca Strait. The following year the number rose to five when Father Augustin Brabant began building his mission at Hesquiaht. “This coast, at the time of our taking possession of it,” Brabant wrote, “was exclusively inhabited by Indians. Four trading posts had, however, been established and were each in the charge of one white man. But besides these four men there were absolutely no white settlers to be found on this extensive coast of nearly two hundred miles [325 kilometres].”

In 1874, the trading post on Stubbs Island consisted of a small store with living quarters attached, surrounded by a large fenced garden. Three shacks stood nearby on the long curving sandspit near the trading post, one of them inhabited by a local man named Gwiar, who acted as Thornberg’s interpreter and tutor while he learned the local language. This may have been the same Gwiar who acted as interpreter a few years earlier during the trial of the two Hesquiaht men found guilty of murder following the John Bright incident. The two other shacks on Stubbs Island, according to Thornberg, “each had an old Man and his Wife. They only came there in the time the Herrings & Salmon run in the harbour—fishing and drying the fish.” Two years later Thornberg built a bigger store with separate living quarters, using wood from a shipment of lumber that washed up near Hesquiaht when the cargo vessel Edwin foundered. Salvaged by Captain Warren, this lumber provided enough material to enclose the new buildings behind “a 6 foot [2 metre] strong Board fence & a strong (double) gate…with a strong wooden barr across.”

Thornberg constantly feared for his life during his many years as a trader. He took no chances at Clayoquot while trading with his customers for furs and dogfish oil. “I traded for years through a hole in the End of the Building it was two feet high & about a foot 6 inches wide [60 by 45 centimetres] & two Ind. could just stand & look in with there elbows & breasts leaning on the bottom part of the hole…On the outside was a small veranda so that the Ind. would be out of the rain when he came to trade.” Despite being married to an Indigenous woman, Thornberg always suspected treachery and murderous intent from the local people, whom he generally called “savages.” He carried his Winchester .44 with him at all times.

When the American barque General Cobb foundered at Long Beach in February 1880, the entire crew, rescued by Tla-o-qui-ahts after being stranded on an offshore islet for two days, eventually found themselves at the Clayoquot trading post. “They received every hospitality..,” reported the Colonist, “in charge of Mr Robert Turnbull.” No mention of Fred Thornberg; possibly Turnbull replaced him at Clayoquot for a while, or took charge during that particular crisis. The General Cobb crew, laden with gifts from their rescuers, travelled with them by canoe to Barkley Sound, where they boarded Peter Francis’s Alert, heading for Victoria.

One night that same year, two men climbed over Thornberg’s fence at Clayoquot and fired a shot through his lighted window. Their flintlock gun misfired, and Thornberg suffered no harm. The attackers came from Nootka, where their people had suffered an outbreak of smallpox earlier in the year, killing ninety people. They blamed all European incomers for their plight, claiming their rivers and drinking water had been purposely infected with the disease in order to eliminate them. Incidents such as this further excited Thornberg’s fears. On July 1, 1882, the British Colonist reported Thornberg taking the law into his own hands during a dispute: “At Clayoquot there was much excitement owing to a shooting affray which had taken place a few days ago, and in which a trader employed at one of Captain Warren’s stations in Clayoquot Sound had fired at and wounded (though not fatally) a Clayoquot Indian.” Thornberg appeared in court in Victoria in November 1883 to answer charges; no further reports appear regarding this incident.

Thornberg’s memoirs indicate that in February 1885 he took charge of the small trading post at Ahousaht. His wife Cecily having died in 1883, in April 1885 he married, “Indian fashion,” Lucy Harbess, an Ahousaht woman. Thornberg appears to have continued running the Clayoquot store, perhaps in rotation with the trading post at Ahousaht, for records show that in 1886, when Warren and Boscowitz sold the Clayoquot trading post to Jacob Gutman and Alexander Frank, Thornberg remained as manager. When Harry Guillod and his wife Kate journeyed to Clayoquot at Christmas 1886, they visited Thornberg and his wife and children, and Thornberg certainly lived there when the sealing schooner Active sank in 1887 during what he described as “one of the worst gales I ever seen in my meny years on the W Coast.” His first child by his wife Lucy, daughter Hilda, was born at Clayoquot in 1889. Thornberg and Lucy had six children together: Hilda, Andreas, William, John, Fred, and a girl who died in infancy. Lucy died of poisoning in 1901 from eating tainted mussels. “I was too late to save her,” lamented Thornberg.

In October 1889, two years after the death of Jacob Gutman and twenty-four Kelsemaht hunters on the Active, Alexander Frank sold the Clayoquot trading post to “two wealthy Englishmen Penney and Brown,” who had recently purchased the sealing schooner Black Diamond, which they renamed Katherine. According to the British Colonist of October 18, 1889, the two intended “not only to engage in the fishing and sealing industries, but also to establish a ship chandlery and general store at which the sealing schooners can refit without having to return to the city.” Four days later, the newspaper reported that Katherine “sailed yesterday afternoon for Clayoquot Sound, having on board the new owners, Messrs Penny and Brown, and a cargo valued at $3000 and consisting of general stores.” To begin the New Year and the new decade, John Lambert Penney inserted a newspaper advertisement about Clayoquot on January 1, 1890, entitled “Notice to Owners of Sealing Schooners.” It declared: “The proprietor begs to announce those interested that the above station carries a complete stock of supplies, etc. to meet the requirements for the coming sealing season…Also to meet the requirements of sealers and others a bi-weekly mail service has been instituted between Victoria and Clayoquot via Alberni.” At the end of the ad, one further detail: “NB Seal skins stored and shipped free of all commission.”

After taking over the Clayoquot store in 1889, John Penney put his stamp on the new enterprise he and Brown had acquired. They released Thornberg, who had by then served fifteen years at Clayoquot, and he moved permanently to Ahousaht. To replace him, Penney brought in one Mr. Smith from Victoria to manage the Clayoquot venture, and shortly afterward, in November 1890, Ralph Smailes, accompanied by his wife, Mary, and their two children, arrived to take charge. On January 7, 1891, the British Colonist reported that Penney had “erected a powerful red light 50΄ high” to aid navigation; this consisted of a metal scaffolding on the northwest sandspit of the island, on which he lit bonfires when expecting a schooner. That year he also became the first postmaster of the proudly acquired Clayoquot Post Office. “Clayoquot Station is the West Coast Post Office,” announced the British Colonist, “the most westerly in the Dominion, [receiving] mail from Victoria bi-weekly.” In 1891, Penney produced a “neat and reliable chart of Clayoquot Sound,” according to the newspaper, and the following year he became the first magistrate and Justice of the Peace in the district. With each of these official appointments, Clayoquot became more firmly established as an emerging settlement. The era of the rough and ready trading post was drawing to a close.

As the first postmaster at Clayoquot, Penney faced stiff challenges. Initially he arranged for mail to come via Ucluelet, then overland to Tofino Inlet, and then by boat to Clayoquot. The April 26, 1890, issue of the British Colonist described the difficulties:

In later years, mail arrived at Clayoquot aboard the regular coastal steamers, a much simpler method.

Although the census of 1891 indicates only a handful of people living at Clayoquot—the Smailes family accounting for four—settlers gradually began to trickle into the region after that date. The earliest settlers who came and stayed in the Tofino area pre-empted land in scattered locations up Tofino Inlet and in various bays; a few pre-empted land out at Schooner Cove and Long Bay (Long Beach). By 1894 these settlers included several whose names continue to be reflected in the area, commemorated in place and street names, and acknowledged as leading pioneers. At the time, all faced the same daunting challenges of raw land, dark forests, endless rain; their lives revolved around clearing land, trying to establish productive gardens, and eking out a living as best they could. Several did some prospecting for minerals. Among these earliest settlers: John Grice, Jacob Arnet, John Eik, George Maltby, William Kershaw, Thomas Wingen, Haray Quisenberry, John Chesterman, Jens Jensen, Bernt Auseth, Ole Jacobsen. Yet none of these could claim to be the first Europeans to try to settle permanently on the Esowista Peninsula; the Evans family had been first.

The previous decade, in the fall of 1881, David Evans, his wife, Hannah, their four young daughters, and three-month-old baby, Virgil, travelled up the coast by sealing schooner and set up home in a rough little cabin somewhere near the site of the present-day government dock in Tofino. In all likelihood, Evans worked in conjunction with Hugh McKay at least part of the time, or he attempted to build on trade relations McKay had earlier established in that location. He tried to operate a small trading business, but he evidently lacked McKay’s experience and proven ability to deal with Indigenous people, even though he spoke the trading jargon fluently. According to family lore, two shipwrecked sailors, rescued by Evans in Tofino harbour, came to live with the family. Only sketchy information survives, but the Evans family, despite assistance from these two men, clearly had a difficult time. Hannah found the life extremely challenging, being the only European woman in the entire area, and David Evans did not draw back from confrontation. Several frightening faceoffs with locals resulted. The worst occurred when the Evans children, who liked to play in the nearby burial ground, took beads and trinkets from the burial boxes. Fearing infection from this contact, Evans burned the burial ground, an outrageous sacrilege in the eyes of the local people. The Evans family lasted only two years before giving up; they traded cedar shakes for a large dugout canoe and left for the Alberni area, later moving near Seattle. In 1904, their son Virgil and his wife, Mary, returned and settled in the emerging community of Tofino, where they remained for many years.

At the Clayoquot trading post, Penney and his partner Brown, who appears to have played only a minor role in the enterprise, continued in charge until the spring of 1893. They sold out that year to Victoria merchant Thomas Earle, by then a man of considerable property. The Fraser River gold rush had lured Earle west from his native Ontario, but having little success as a miner, he moved to Victoria in 1862. There he found work as a bookkeeper in J. Rueff’s grocery business. In 1867 he set out for the Big Bend gold rush on the upper Columbia River, where he ran a successful general store at French Creek, supplying miners. Returning to Victoria, he bought into Rueff’s business, and following Rueff’s death in 1873, Earle took over the business. By 1881, Earle’s Victoria Coffee and Spice Store on Wharf Street at the foot of Johnson Street was prospering nicely. That year Earle branched out and invested in railways in Washington and Oregon as well as on Vancouver Island, and two years later he also became a founding shareholder and board member of the Canadian Pacific Navigation Company, working alongside many prominent businesspeople. In the 1880s, Earle also became interested in the salmon canning industry, investing in the Alert Bay Canning Company on Vancouver Island’s east coast, the first cannery between the Skeena and the Fraser Rivers. In 1888 he became part owner of the cannery, joining forces with Stephen Allen Spencer, a Victoria studio photographer of some note, who had helped found the operation in 1881, producing canned salmon under the Nimpkish brand name.

In order to serve his Alert Bay cannery and his dry goods business, the energetic Earle acquired seven boats “of about 100 tons each,” including the steamer Mystery, which he had built in 1890 at the cost of $20,000. In 1900, flush with his commercial success, he hired Victoria architect Thomas Hooper to build a modern office and warehouse on Yates Street in Victoria. This building still stands, now designated a heritage building. In addition to his widespread commercial interests, Earle involved himself in federal politics; Victorians elected him as their Conservative Member of Parliament in 1891 and twice more, in 1896 and 1900.

By the time Earle acquired the Clayoquot store in 1893, this establishment had become the most important settlement on the west coast north of Victoria. J.C. Brocklehurst served as its second postmaster, remaining there just over a year, and then Earle appointed Filip Jacobsen to manage the store; in 1895 Jacobsen became postmaster. Described by Cliff Kopas in his book Bella Coola as “long, lean, learned and loquacious,” Jacobsen had been living on the coast of British Columbia for some time. His facility in the Chinook trading jargon, and his experience and ease in trading with coastal people, made him an ideal employee. Some years before, in 1888, Jacobsen pre-empted 65 hectares of land in the Bella Coola region, and he had been involved in promoting the area for settlement. Later a large number of Norwegians would settle there, encouraged by Jacobsen. In his travels on the coast, Jacobsen often visited Alert Bay, where he came to know Stephen Spencer, Earle’s partner in the cannery.

Jacobsen had first arrived in British Columbia in 1885 to acquire First Nations artifacts for the Berlin Royal Ethnological Museum, working alongside his elder brother Adrian. The two brothers scoured the coast, collecting artifacts, and later that year returned to Germany with a group of nine Bella Coolas (Nuxalk). This group spent thirteen months in Europe, appearing at various zoological gardens as living ethnographic displays. They demonstrated their hunting skills, their gambling games, and their dances, including elements of the exotic cannibalistic ritual called the hamatsa. Huge audiences gathered to see them, up to 3,000 people at a time. The Bella Coolas wore European clothes, learned some German, and came home unscathed, escorted by Filip Jacobsen.

Meeting these Bella Coolas in Germany proved to be a turning point for the young German ethnologist Franz Boas, introducing him to First Nations culture of the West Coast. The following year Boas visited the coast for the first time and started his ethnographic work, collecting bones and skeletons. By 1890 he had some 200 skulls from all over Vancouver Island. From the outset, this type of collecting stirred up resentment and protest, and it also required the collaboration of knowledgeable agents in the field, among them the Jacobsen brothers.

The Jacobsens and others, including, to varying degrees, most of the storekeepers and traders on the coast, played an essential role in another form of collectors’ mania that struck the Pacific Northwest. Throughout Europe and North America, northwest coast cultural artifacts of every description had become objects of desire: potlatch paraphernalia, masks, hats, carvings, totems, cedar implements. Museums and private collectors scrambled to obtain this material, particularly from the mid-1870s to the end of the century. With the active participation of experienced local traders from Vancouver Island and Haida Gwaii to the central BC coast and up to Alaska, hundreds of thousands of items left the northwest coast in crates, loaded on board schooners and steamers. Entire boxcars filled with such material then travelled by train across North America.

Ever since the first European contact on the West Coast in the 1770s, the highly crafted artifacts and cultural items of First Nations people attracted avid attention from the newcomers. No fewer than twelve members of Captain Cook’s crew gathered material, including both domestic and ceremonial items, that ended up in the British Museum or in private collections. Alejandro Malaspina for Spain and George Vancouver for England had specific instructions to gather “artificial curiosities” and exotic items to bring home. Malaspina spent fifteen days collecting materials in Nootka Sound, destined for the Royal Museum in Madrid. Much of the material amassed by these early visitors in the eighteenth century eventually found its way into collections and museums ranging from Cambridge to Florence, from Vienna to Helsinki, exciting further interest. By the latter decades of the nineteenth century, major American museums aggressively led a renewed hunt for artifacts, the first hint evidenced in 1863 when the Smithsonian Museum circulated a request to interested parties all over the West Coast, including Vancouver Island and British Columbia, indicating it wanted to extend “its collections of facts and materials” about northwest coast peoples, stressing immediacy because “the tribes themselves are passing away or exchanging their own manufactures for those of the white race.”

According to Douglas Cole in his book Captured Heritage, a perfect storm of events conspired in favour of the collectors, with rapid expansion of museums all over the world being funded by burgeoning industrial capital at a time of expanding colonialism and settlement. Simultaneously, the “calamitous decline of the native population…must have created a surplus of many objects at precisely the period of the most intense organized collecting.” Put starkly, in some coastal communities, more ceremonial artifacts may have existed than people able to use the items. The diminishing population of Indigenous people had little defence, with their increasing dependence on a cash economy, local middlemen pressuring them to sell, and priests and politicians undermining the value of their traditions.

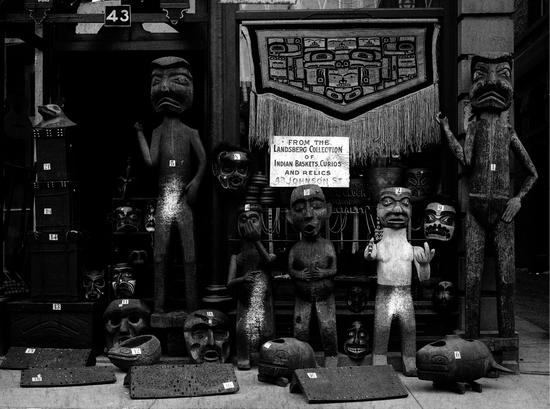

At Clayoquot and other coastal trading posts, the traders and storekeepers handled special requests from collectors seeking large items like totem poles and dugout canoes, and they also began to supply the busy handful of “Indian curio” shops that sprang up in Victoria. The early tourist trade emerging in that city in the 1870s displayed a keen appetite for carvings, baskets, and totems, an appetite that grew over time. Between 1880 and 1912, five different curio businesses operated in Victoria. While they serviced the special needs and requests of collectors and curators, these curio dealers also supplied the hungry and less discerning tourist market. Aaronson’s Indian Curio Bazaar on Government Street claimed to be “the cheapest place on the Pacific Coast to buy all kinds of Indian Baskets, Pow-Wow Bags, Wood and Stone Totems, Pipes, Carved Horn and Silver Spoons, Rattles, Souvenirs, Novelties, Etc.” Over on Johnson Street, Hart’s Indian Bazaar respectfully invited the public, “especially tourists,” to visit this shop with the “largest and finest assortment of curios on the Pacific coast.” At Stadthagen’s Indian Trader, 79 Johnson Street, collectors could buy not only trinkets and baskets, but also large totem poles.

Indigenous carvers and weavers on the West Coast began producing goods specifically for the tourist trade, often selling through middlemen like Filip Jacobsen and later Walter Dawley at Clayoquot. A steady market developed for baskets, mats, carvings, totem poles, silver jewellery, spoons, plates, and ceremonial gear. As time passed, collectors and dealers became increasingly particular, alarmed by the influx of “tourist-quality” curios and artifacts. Walter Dawley’s correspondence contains a number of insistent requests for fine-quality carvings and baskets, specifically rejecting the items made for tourists, or those using European dyes. Nonetheless, this tourist trade material found, or perhaps even created, its own thriving market that continued to grow. Years later, in the mid-1940s, biologist Ed Ricketts commented on this when visiting Clayoquot. Admiring the “old, dull colours” of older artifacts and totems, and seeing the art teacher at Christie Indian Residential School trying to encourage students to study and practise their own traditional art, he wrote, “It does only limited good for us to encourage them…in their own sturdy primitive art [for] when they get back out, what tourists they see will search out and buy the shoddy, gaudy, highly coloured things.”

Once established at Clayoquot as store manager and postmaster, Filip Jacobsen proved himself an energetic leader in the emerging settlement. He encouraged other Norwegians to come to Clayoquot, just as he had done in the Bella Coola district. In November 1894 he wrote to the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works for British Columbia, asking him to set aside land for his fellow countrymen. “I have been out here on the West Coast round Clayoquot Sound specially and I have come to the conclusion that there is an opportunity to have another Norwegian settlement…I will try to get another settlement of honest and sober men…a lot of fishing could be done.” Jacobsen’s letter prompted the commissioner to write back that the government would survey the land around Clayoquot as soon as possible.

The first of many Norwegian settlers who settled in the Tofino area had already arrived by the time Jacobsen wrote this letter, and they had already scouted out the land they wanted. By the end of 1894, Jacob Arnet, Thomas Wingen, Jens Jensen, and Bernt Auseth, all in their early twenties, had registered their land pre-emptions: Arnet, Wingen, and Auseth in Mud Bay (Grice Bay), and Jensen in Jensen Bay, nearer to what would become Tofino. Other Norwegians soon followed, including John Eik, who left Norway in 1891, eventually finding work on a halibut schooner working out of Seattle. His boat put in to Clayoquot Sound during a storm, and the area reminded him so strongly of Norway that Eik vowed to return. He sailed his own sloop up the coast in 1895, accompanied by Ole Jacobsen. The following year, Eik pre-empted 60.7 hectares where Tofino now stands and put up a simple cabin, later building a float house to live in. In 1903, Eik returned to Seattle to marry Serianna Flovik, recently arrived from Norway, and they came back to Clayoquot together. Anton and John Hansen joined the Norwegian settlers in the early 1900s; their sister Julie had already preceded them to Clayoquot, having married Tom Wingen in 1894. Other Norwegians arriving in the area included John Engvik, Michael Haugen, Jacob Knudsen, Ole Larsen, and S. Torgesen.

Jacob Arnet became a leader of the emerging settlement, establishing himself on his 53.4 hectares fronting on Mud Bay. He had worked his way west from Minnesota, eventually gill-netting for the Fraser River canneries in a rented boat, saving to buy his first boat, a robust 6.7-metre sailing vessel. According to his son Trygve Arnet, interviewed in 1981 for Settling Clayoquot, “[Jacob] sailed up the west coast and fished in Nootka Sound…They sent the Scandinavians up there because they knew the process. A firm in Victoria would hire a gang of them and send them out.” In 1896, having cleared some land and built a small house, Jacob sent for his sweetheart Johanne to join him; they had not seen each other since he left Norway in 1892. She travelled to Victoria in the company of Jacob’s brother August, and on May 27, 1896, she and Jacob were married. Their first child, Alma, was born at Clayoquot the following year; six sons followed. A dynasty of west coast Arnets had begun, assisted by the arrival of Jacob’s brothers August, Sofus, and Kristoffer, who all followed his lead and settled in the area. When Jacob’s grandson, Edward Arnet, arranged a centenary family reunion in Tofino in 1994, some 175 Arnet descendants attended.

John Grice of Newcastle-upon-Tyne became the earliest British settler in the area. Grice arrived in Victoria with his son Arthur in 1891, and he quickly found work aboard the sealing schooner Mascot. He does not appear on the Clayoquot census for 1891, but he showed up there that year, scouting for land. On May 1, 1893, he pre-empted 83.3 hectares at the head of the Esowista Peninsula, where much of Tofino now stands. Initially, few settlers were interested in this area of land on the peninsula: the Norwegians clustered around Grice Bay; James Goldstraw, George Maltby, and William Kershaw took up land in Schooner Cove; John Chesterman chose a wide swath of land spanning the narrow neck of the peninsula, extending from the beach that now bears his name over to Jensen Bay; and Haray Quisenberry and his wife settled near Cox Bay.

Some of these new arrivals hoped to farm on their clearings in the bush, bringing with them cows or chickens; some wanted only a shack to use as a base camp when they went out prospecting and trapping. Many were unmarried, or if married, their wives tended to join them later. For all of these settlers, Earle’s establishment at Clayoquot served as their “town,” with its post office, store, and the visiting traffic of sealing schooners and coastal steamers.

From the early 1890s, potential customers looking to buy goods, trade furs, or exchange local news had another option. Across the harbour from Clayoquot, on an island near Opitsaht, Thomas Stockham and Walter Dawley set up shop as general traders in direct competition with Thomas Earle. Stockham had arrived in Canada from his native England in 1879, and by 1890 he turned up in Victoria, finding employment with a surveying crew. Dynamic and energetic, always keen to try new ventures, Stockham developed a liking for the west coast during his season of surveying. His name pops up on the 1891 census for Kyuquot, giving his occupation as “farmer,” an unlikely description for a man destined to be a wheeler-dealer. Stockham found his way down to Clayoquot and by February 1894 had pre-empted the fourteen-hectare island that still bears his name; two years later he received a Crown grant to the island. He had established himself on the island before 1894, because by then he had already opened the store that became known as Stockham and Dawley’s. How Stockham met his business partner, Walter Dawley, remains uncertain. Possibly they met over a drink in Victoria during the brief period in 1892 when Dawley worked in the city as a bartender. Hailing originally from Morrisburg, Ontario, Dawley had come west to Victoria in his early thirties, perhaps to get away from the family farm, perhaps to seek his fortune in new surroundings. In 1894, Dawley pre-empted land out at Schooner Cove, his first acquisition of many.

To build their store, Stockham and Dawley used “shipwrecked lumber from Schooner Cove on Long Beach, rafted it and towed it down with a canoe nine miles [14.5 kilometres], not even a row boat available,” according to a scrap of memoir left by Dawley. This lumber came ashore near Dawley’s land, the event reported in the Colonist in May 1893. “A big load of lumber…drifted on to the beach at Long Beach...Some settlers are at work trying to save the lumber, the place where it drifted ashore being very shoaly, where an immense surf breaks in from the ocean. Owing to its position no steamer could pick it up conveniently, and as there is such a large quantity there Captain Foote thinks the settlers can only save a comparatively small portion of the cargo.” Enough, however, to build a store.

Through the mid- to late 1890s, Stockham and Dawley went from strength to strength as traders on Stockham Island, pursuing all possible means of gaining influence in local commerce and politics. They took out a number of mining claims and continued to pre-empt more land. Before the end of 1896, Stockham had acquired not only his island but also land at Long Bay, at Mud Bay, and in Sydney Inlet. Dawley eventually owned seven parcels of land, taken out either in his or, following his marriage in 1908, his wife Rose’s name. His brother Clarence, who joined him on the coast in 1900, staked many mineral claims around Clayoquot Sound and up at Nootka, and he also acquired several tracts of land.

Having a taste for influential positions, by 1895 Walter Dawley had become a Justice of the Peace for Clayoquot. In 1898 he became the first mining recorder in Clayoquot Sound, a shrewd move that ensured all prospectors and miners passed through the Stockham Island store to record mining claims. Critically for their business, Stockham and Dawley fostered close relationships with the sealing captains, always striving for a monopoly on their trade. Dawley became a powerful middleman in recruiting Indigenous crews for the sealing schooners, and because Stockham Island lay so near the village of Opitsaht, the two storekeepers became well acquainted with the Tla-o-qui-aht people living there. According to George Nicholson in his book Vancouver Island’s West Coast, particularly good relations existed between Dawley and the Tla-o-qui-aht’s Chief Joseph and his wife, Queen Mary. Yet although business seemed set to prosper on Stockham Island, the two traders knew their location to be flawed. The place did not offer a good anchorage or anywhere to build a substantial dock, and the small, rocky island offered few opportunities for future development and little space for expansion. Earle’s establishment at Clayoquot, in that respect, definitely held the upper hand.

Clayoquot gained an even higher profile in the mid-1890s with the appointment of a resident policeman. Constable Frederick Stanley Spain first showed up there in 1894; provincial police records reveal that he received a total of four months’ pay ($60 per month) that year for policing great stretches of Clayoquot Sound from Stubbs Island. The following year he took up his position there full time, patrolling his domain mostly by rowboat, doing his utmost to stop sealing captains selling liquor to Indigenous people, among other challenges. He would travel by steamer to far-flung locations to carry out his work, ranging as far as Kyuquot. Spain pre-empted 28 hectares on Stubbs Island in 1896, the entire southern section of the island.

Several years after his arrival, Spain’s cousin, Dr. P.W. Rolston, arrived at Clayoquot, the first resident doctor on the west coast. With his wife and young family, Rolston disembarked from the steamer Willapa in September 1898; they remained on Stubbs Island for over two years. Probably to her relief, Mrs. Rolston discovered she had female company there: Helga Jacobsen, who married Filip in 1894; Marion Spain, who married her policeman husband in 1895; and from 1899, Annie Brewster, who lived there with her family and husband, Harlan, at least some of the time. Harlan Brewster succeeded Jacobsen as store manager and postmaster in 1899, living at Clayoquot for several years. Better known locally for his later work as cannery owner and manager at Kennfalls, Brewster eventually took up a career in politics that culminated in a brief stretch as provincial premier.

Recollecting her time at Clayoquot, Mrs. Rolston wrote of “the long low line of buildings…in the trading establishment,” and the comforts of eating “excellently cooked meals as a good Chinese cook can produce” in the large dining room in the Jacobsens’ home. Her vivid recollections of how “every day brings fresh miners and prospectors…with a feverish desire to get gold and other precious metals” led her to conclude that, “by and by, no doubt there will be men and means to make this a western port of great importance.”

With the growing numbers of prospectors and settlers on the coast and the increasing maritime traffic, Thomas Earle decided in 1898 to improve his dock. An upgrade was badly needed, for according to Mrs. Rolston “the storekeeper’s wharf [was] not…serviceable at low tide.” Earle built an ambitious structure, a long curving dock, extending far out from shore with a trolley running on narrow steel tracks from the store to the end of the dock. This would facilitate the loading and unloading of goods from the Canadian Pacific Navigation Company’s new steamer Queen City. This 36-metre-long passenger and cargo steamer, resplendent with electric lights, began making twice-monthly runs up and down the coast beginning in December 1898, largely replacing the much-derided old “washtub” Willapa that had doggedly plied the coast for some years. Also in 1898, Earle built a hotel to accommodate visitors, prospectors, sealing captains, would-be settlers, and those awaiting passage on the steamer.

Given the comings and goings at Clayoquot, and with the perpetual problem of trying to control the unscrupulous sale of liquor, the harassed Constable Spain faced constant challenges in performing his duties. The constable’s job, extending as it did throughout Clayoquot Sound, never promised to be easy, but he found his duties rendered even more difficult by the lack of co-operation from the Justices of the Peace along the coast. These JPs generally included the better-known and more influential settlers. According to a letter of complaint Spain wrote to the Attorney General on November 22, 1900, all of these JPs, everywhere on the west coast from Clo-oose to Quatsino, failed to do their duty properly. He reserved his most severe criticisms for the four JPs at Clayoquot. In his estimation, the “administration of the law has been most glaringly miscarried on many occasions” thanks to the local JPs: Walter Dawley, because he would never sit in judgment on any case that might be against his commercial interests; Dr. Rolston, because he would not prejudice his medical practice; George Maltby, because he lived at Long Bay and found it difficult to come to Clayoquot to hear cases; and John Grice, “the oldest and most unfit,” being “under the thumb of Mr Dawley.” Quite possibly this condemnation arose in part because Grice had lively sympathies with the Indigenous folk; as shipping master at Clayoquot he saw a great deal of their interaction with the wily sealing captains, including the bribing of hunters with liquor and the encouragement of gambling on board. Yet clearly, with most JPs unwilling to hear cases, or having strong personal prejudices about each and every local misdemeanour, Constable Spain faced an uphill battle. He remained at Clayoquot, coping as best he could, until 1902, when he moved to New Westminster.

One of the more notable events during Constable Spain’s tenure as police constable at Clayoquot occurred when the three-masted American brigantine Hera foundered right in Tofino Harbour. On November 25, 1899, Clayoquot settlers found themselves in the thick of the excitement when this stricken ship, on fire and utterly doomed, drifted in sight of their homes on Stubbs Island. Harlan Brewster, busy unravelling Filip Jacobsen’s account books, happened to be at Clayoquot that day during the cannery’s off-season. Along with Jacobsen, Constable Spain, and three other men—Nigel Campbell, Thomas Carr, and S. Torgesen—Brewster took part in a remarkable rescue mission, observed anxiously by the ladies on shore, including Mrs. Rolston, whose description of the shipwreck and rescue was published in the Colonist. With great misgivings, she witnessed her husband’s cousin, Constable Spain, embarking on this hazardous venture, going to the aid of a ship they initially believed had struck a rock. “I think you can imagine…my anxiety, as well as Mrs. Jacobsen’s and Mrs. Brewster’s whose husbands went also. It was a very brave act as they encountered a great deal of danger.”

Hera had sailed from Seattle on November 18, fully loaded and heading to Honolulu in the charge of Captain J.J. Warren. Her 700-ton cargo included 1,800 barrels of lime; 1,000 cases of bottled Rainier beer; 2 carloads of tinware; a carload of tinned corn; 10 pianos; 50,000 board feet of lumber; and a quantity of wheat, oats and bran, not to mention part of a church that had been built in Wisconsin, which was carried as deck cargo. After sheltering for several days at Clallam Bay, WA, to escape the stormy weather, Hera had ventured out, running into a terrific southeaster that drove her northward up the coast of Vancouver Island. Off Clayoquot, the incoming sea water made contact with Hera’s cargo of lime, setting it and the ship on fire. The captain ordered a distress flag, a red tablecloth, be hoisted, and he aimed for the nearest land. By the time Hera approached the entrance to Tofino Harbour, she had been burning for twenty-four hours, with the frenzied crew trying to contain the fire below decks. With her sails blown out and smoke pouring from nearly every seam, the ship wallowed helplessly. The captain loaded himself, his daughter (the only female passenger), and three others into Hera’s lone lifeboat and set out for shore.

The six rescuers from Clayoquot battled through the heavy seas in their rowboat toward the burning ship. As they passed Hera’s lifeboat carrying the ship’s captain and his passengers, they shouted back and forth, trying to get a picture of the situation. When the rescuers arrived beside the fully engulfed ship, according to Mrs. Rolston they found “desperate men ready to jump into the boat as soon as she came near enough. Of course if they had done this the boat would have been swamped and all drowned, and it was only by standing up with axes in hand and calling out that the first man who jumped in would be killed that this was prevented. Then one by one they were safely got on board. By this time the whole ship was red hot.” The five crewmen, and their rescuers, made it safely ashore.

The abandoned Hera continued drifting toward shore, observed with fascination by Mrs. Rolston:

The ship burned to the waterline, with only her masts left visible. Remarkably, much of her cargo, including the beer, remained intact, as later salvage efforts revealed.

Captain Warren faced stern criticism for taking the only lifeboat and abandoning his ship with men aboard. “The Captain of the burning ship acted like a brute,” wrote Mrs. Rolston indignantly. “There was only one boat, and he and the owner of the vessel, with his daughter and 2 men, got into it and left the others to perish. [Those left aboard] had built themselves a raft, but it would have been worse than useless in such a sea.” The Royal Humane Society awarded each of the Clayoquot rescuers its bronze medal, and the US State Department acknowledged its “keen appreciation of the gallantry and heroism displayed” by the Clayoquot men, authorizing the American consul in Victoria to present each of the six men with a gold lifesaving medal on behalf of the US president. In 2012, the gold medal presented to Nigel Campbell showed up in the hands of a coin dealer in the United Kingdom; through the efforts of David Griffiths of the Tonquin Foundation in Tofino, the coin has been returned to the west coast.

In 1974, John Svoboda, a local crab fisherman, hooked the sunken remains of the Hera off Felice Island, and local diver Rod Palm went down to investigate, finding a world of shipwrecked wonders half buried in the sand: “deck knees, ship’s rigging, deadeyes and bottles everywhere,” as David Griffiths enthused in his 2002 Tofino Time article about the find. Thanks to the efforts of Rod Palm and others, the wreck of the Hera became British Columbia’s first protected underwater heritage site.

Over on Stockham Island, Walter Dawley and Thomas Stockham had been thoroughly upstaged by Earle’s new dock and hotel at Clayoquot. They must have been infuriated, for earlier in 1898 they too had opened a hotel, the very first on the west coast. Catering largely to prospectors and sealing captains, their six-bedroom establishment lacked the graces of the sixteen-room hotel at Clayoquot. There, visitors could find a private ladies’ dining room and refinements such as potted plants in the dining room, framed pictures on the wall, and even looking glasses and rugs in several of the bedrooms. The hotel on Stockham Island had few of the finer things of life, apart from a stuffed pelican decorating the saloon, although it was liberally supplied with spittoons. As for the fancy new dock at Clayoquot, it could only remind Stockham and Dawley of the sketchy facilities at their own establishment. Described by the Colonist in April 1900 as “a flimsy and dilapidated structure,” their dock eventually collapsed completely under the weight of cargo from the steamer Willapa. So Clayoquot held all the cards: excellent dock, good moorage, better hotel, regular visits from Queen City, large expanse of flat, easily accessible beach waterfront. Still, the two traders on Stockham Island persevered, building powerful trading relationships on the coast, biding their time, keenly alert to future opportunities, and always keeping a close and suspicious eye on developments over at Clayoquot.

Stockham and Dawley did have one potent advantage over Earle’s enterprise at Clayoquot; their strong influence up the coast through their satellite stores. In 1894 they opened a store at Yuquot, employing John Goss as manager, and in 1895–96 they opened a store at Ahousaht, with Fred Thornberg in charge. These stores gave them a firm hold on Indigenous trade in goods and furs, and a powerful role in provisioning and assisting the sealing schooners. Brokering deals between sealing captains and local sealing crews became central to their business. The best seal hunters on the coast came from Opitsaht and Ahousaht; to organize their employment and to corner their custom translated into a lot of money. Stockham and Dawley would offer advances on wages during the sealing season, which all too often meant that local hunters, having equipped themselves at Stockham and Dawley’s stores, went hunting while their families lived on credit; the hunters often returned to find themselves more in debt than when they left.

Because most of Stockham and Dawley’s inbound correspondence has survived, a vivid picture of their commercial world can be pieced together. Their correspondents ranged from prospectors to sealing captains to earnest settlers requiring information or credit. From up the coast, the storekeepers in Nootka and Ahousaht—particularly Fred Thornberg—bombarded their employers with letters about everything imaginable: dogfish oil, damp flour, aggrieved descriptions of unloading goods from coastal steamers in the pouring rain. Everyone who owned pen or pencil on the west coast seems to have written to Stockham and Dawley at some point: politicians, prospectors, missionaries, Indian agents, curio collectors, Indigenous customers—even the rival storekeeper at Clayoquot on Stubbs Island. At one point, Harlan Brewster wrote to ask to borrow Stockham and Dawley’s piledriver, and letters survive showing Brewster and Dawley united in opposition to their common foe, “the Chinaman.” In one letter, Brewster suggested to Dawley that they “load the Chinaman to his destruction financially with furs at high prices.”

Around 1901 this “Chinaman,” Sing Lee, had established his store over on the Esowista Peninsula, near the present site of the government dock in Tofino. Initially, Sing Lee probably worked on a small scale, selling and buying furs, and stocking only basic provisions for early Chinese gold prospectors. With increasing traffic in the area, and with a growing number of Chinese gold seekers and itinerant workers coming and going, Sing Lee’s trade escalated, becoming ever more of an irritant to the other traders. Dawley repeatedly demanded that his suppliers refuse to deal with Sing Lee; some suppliers cravenly complied, but the feisty Victoria wholesaler Simon Leiser retorted, “You are getting the goods cheaper than the chinaman or anybody else…why you should kick I do not know.” Sing Lee remained in the area, buying furs, trading, and seeking gold until his death in 1906. Well known on the coast, a frequent traveller on the coastal steamers, his death received a lengthy mention in the Victoria newspapers—at the time, an unusual tribute for a Chinese person.

Descriptions of social life among settlers in the early years rarely surface, but on occasion Filip Jacobsen welcomed groups for celebratory events. The Colonist describes how thirty people gathered at Clayoquot for a New Year’s Day dance and celebration in January 1896, in the “new building erected by the Clayoquot Fishing & Trading Co, which had been most tastefully decorated for a magnificent banquet provided by Mr Jacobson, the manager.” This event could very well have taken place up Tofino Inlet at the recently constructed Clayoquot cannery. Following many “loyal and patriotic toasts,” the assembled crowd, including a good number of Norwegians, drank to the health of the Queen. John Grice then spoke at length of the connections between the British empire and the Norse people; Father Van Nevel, the Catholic priest living at Opitsaht, waxed eloquent about the help settlers provided in his missionary work, and another Catholic father recited a short poem in Chinook, complimenting the Clayoquot chief. John Chesterman rounded off the evening with his “humorous versatility” and his impersonation of Santa Claus.

Several months later, Filip Jacobsen organized another remarkable event. To celebrate Queen Victoria’s birthday in May 1896, a sports day took place at Clayoquot, with aboriginals “in gala attire.” Among the judges of the competitions: Constable Spain; Father Van Nevel; Harry Guillod, the Indian agent at Ucluelet; and Chief Joseph of Opitsaht. Canoe races, sack races, every type of race imaginable offered prizes ranging from hats to shoes to silk neckties—even a new bonnet for one of the ladies’ events. Jacobsen did not know at the time, but he had set a precedent for what later became known as “Clayoquot Days.” For decades, local people consistently gathered at Clayoquot on the May long weekend for community picnics and for sporting events. Sometimes such events also took place at Clayoquot on Dominion Day, now called Canada Day—the first of July.

After Harlan Brewster took over as manager and postmaster at Clayoquot in 1899, Filip Jacobsen briefly took up mining, but eventually he returned to the Bella Coola area. He remained there until his death in 1935. Brewster remained in charge of the Clayoquot store for just over two years, during which time Thomas Earle ran into severe financial difficulties. Back in 1891, Earle had entered federal politics, and his business ventures began to suffer. He also had invested heavily in an American railway that drained his resources to the point he declared bankruptcy in December 1901, much to the shock of the business community in Victoria. Earle never recovered his losses and died financially broken in Victoria in 1910.

Rumours of Earle’s impending bankruptcy reached the ears of Walter Dawley and Thomas Stockham early in 1901. They acted quickly to acquire his business interests at Clayoquot, and in February 1902 they bought out Earle’s entire holdings on Stubbs Island: land, store, hotel, and dock. Turning their backs on Stockham Island, they moved across the harbour. With their two satellite stores up the coast at Ahousaht and Yuquot, with their business interests flourishing, and with all the facilities of Clayoquot at their disposal, Stockham and Dawley became the most influential businessmen on the west coast north of Victoria. Dawley became the new Clayoquot postmaster, a position he held until 1937. The Methodist medical missionary Dr. McKinley, who succeeded Dr. Rolston, shortly afterward took over their original establishment on Stockham Island. The Methodists eventually purchased the property from Stockham and Dawley for $1,500 and transformed the former hotel into a small hospital.

The summer of 1902 saw much agitated lobbying about the telegraph line being extended from Alberni toward Clayoquot. John Chesterman and other settlers wanted the line to terminate on the peninsula, where they firmly believed a new townsite would emerge. Dawley and Stockham wanted it to extend to Stubbs Island by underwater cable. They had their way, and in December 1902 the telegraph instruments were installed at their store, and the telegraph connection to the outside world came alive, radically changing the nature of communication on the coast.

Without doubt, Stockham and Dawley helped set in motion a new and dynamic era in the history of Clayoquot Sound—although perhaps not in the manner they originally wished. Given the burgeoning activity locally, it became evident that a permanent community would emerge. However, apart from a few stubborn settlers like John Chesterman and John Grice, no one at first believed that a community would spring up on the Esowista Peninsula, nor that it could ever eclipse Clayoquot on Stubbs Island. Walter Dawley dismissed the entire notion. He had established himself at Clayoquot confident that all future settlement and commercial activity would take place right there on Stubbs Island. He was wrong.