Chapter 5: “Outrages and Disorders”

With the sea otter population depleted to the point of near extinction, few fur trading ships entered Clayoquot Sound in the decades following the Tonquin incident of 1811. The incentive to trade for furs on the hazardous West Coast largely disappeared, as events to the south and east took precedence.

In order to secure British claims to Vancouver Island, in 1843 the Hudson’s Bay Company founded Fort Victoria on the southern tip of the Island. James Douglas, then the company’s chief factor in Fort Vancouver, at the mouth of the Columbia River, selected the site, surveyed the land, and supervised construction of this new outpost. Six years later, in 1849, Douglas moved to Fort Victoria to take charge when Victoria replaced Fort Vancouver as the headquarters of the fur trade on the Pacific coast. That same year, the British government established Vancouver Island as a Crown colony, ceding it to the Hudson’s Bay Company for seven shillings a year, on the understanding that the HBC would administer affairs in the colony and encourage settlement.

Throughout the 1850s, the settlement of Fort Victoria, and indeed the entire Colony of Vancouver Island, failed to amount to much. Few settlers arrived, partly because land cost one pound an acre (half a hectare) in the colony, whereas in America land could be had for free, and also because many would-be settlers followed the lure of gold to California after the first exciting discovery there in 1848. Even employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company abandoned the new colony and went south. Vancouver Island could not compete. “It is in my view worthless as a seat for a colony,” Archibald Barclay, the HBC secretary, declared, adding that Vancouver Island was the “last place on the globe” he would select as an abode.

By early 1851, only twenty settlers had taken the rash step of purchasing land in the colony, and four years later the entire European population on Vancouver Island came to only 774, of whom nearly half were children. These settlers clustered around four locales on the east coast of the Island: Fort Victoria (now the City of Victoria), the Cowichan valley, Fort Rupert (Port Hardy), and Nanaimo. At that time, no one even imagined settling on the remote west coast of Vancouver Island.

After Britain declared war on Russia in 1854, involving itself in the Crimean War, gunboats of the Royal Navy’s Pacific fleet, then headquartered at Valparaíso, Chile, began to make use of Esquimalt Harbour near Victoria as a strategic supply base for their excursions into the North Pacific. Following a British naval attack on Russian fortifications on the Kamchatka Peninsula, three Royal Navy ships carrying eighty wounded men entered Esquimalt Harbour seeking assistance. Fort Victoria could not provide the required medical aid, and the ships continued on to San Francisco. Anticipating more casualties, in 1855 James Douglas ordered the construction of three rough little hospital buildings at Esquimalt Harbour. No further casualties showed up, so these buildings never served their original purpose, but from that time forward, naval vessels regularly appeared in the harbour. A decade later, in 1865, Esquimalt officially became the new headquarters of the Pacific fleet, and by then Victoria had changed beyond recognition.

Gold fever had transformed the place. In 1858, the discovery of gold along the Fraser River saw Victoria explode in size. Some 30,000 prospectors, mostly Americans, flocked up the river after first going through Victoria because the colonial government required them to obtain their licences there. Within a couple of years, many of them had continued north along the Fraser into the interior of British Columbia, discovering more gold in the Cariboo region. By 1862 the gold discovered near Barkerville set off another stampede, attracting tens of thousands more prospectors through Victoria. From a quiet backwater of about 800 people in 1858, for a few mad years Victoria became “a rowdy boisterous, transient settlement,” according to historian Terry Reksten, with “saloons and hotels and shanties [crowding] the palisades of the fort.” Prices soared, a city of grey canvas tents sprang up, and at times during the dry summer months, “liquor was cheaper than water.” The Cariboo gold rush alone extracted an estimated $30 million in gold during the 1860s—an exceptional return considering that gold then sold for around $20 an ounce.

On the west coast of Vancouver Island, the middle years of the nineteenth century saw far less European activity than the decades immediately following first contact. By the early 1850s, a few independent coastal traders cruised the coast in small schooners, reviving trade with the coastal tribes. These traders undertook annual and semi-annual tours, usually each autumn when the annual hunting, fishing, and gathering had ended. They would stop at various villages along the coast, exchanging trade goods for dogfish oil, whale and seal oil, fresh and dried fish, berries, and furs. They carried out business in much the same way the earlier sea otter traders had done, negotiating with the chief of each tribe after the appropriate ceremonies and exchanges of gifts had taken place.

Once the trading parties negotiated a price, the close personal and economic ties among the Indigenous people in their far-flung communities meant that the established price would be maintained all along the coast. In his book The Nootka: Scenes and Studies of Savage Life, first published in 1868, Gilbert Sproat noted, “News about prices…travels quickly to distant places from one tribe to another. If a trading schooner appeared at one point on the shore and offered a higher price than one usually gives, the Indians would know the fact along the whole coast.” Sproat described the Nuu-chah-nulth as “astute, and rather too sharp at bargaining.”

During the 1850s a vigorous trade emerged along the coast with the growing demand for dogfish (Squalus acanthias) liver oil. The developing resource industries throughout the Pacific Northwest began to require immense amounts of it. Loggers used dogfish oil to grease their corduroy skid roads and to lubricate machinery, and miners to light their lamps in the coal mines opening at Fort Rupert and at Nanaimo. Two early lighthouses even used dogfish oil to fuel their beacons. Governor Douglas commended this new enterprise in 1855: “The oil procured from this colony is procured from Native tribes inhabiting the west coast of Vancouver Island. It is of excellent quality, and has a high character in California where it brings from three to four dollars a gallon [4.5 litres].” That same year Douglas estimated that 10,000 gallons (45,460 litres) of dogfish oil had been purchased along the west coast of Vancouver Island.

The demand for dogfish oil increased yearly, resulting in a profitable trade for Indigenous people along the coast. In July 1864, Robert Brown visited the west coast as commander of the Vancouver Island Exploring Expedition, and noted in his diary: “The dog-fish season is just commencing. Laughton [coastal trader Thomas Laughton] calculates that from Pachena to Woody Point [Cape Cook] there is about 15,000 gallons [68,000 litres] of Dog-fish oil traded every year…This does not include what is…traded by the Indians to the Americans…The Clay-o-quot Chief is a great trader & collects oil of the neighbouring tribes; he then goes over to Cape Flattery and sells it for American goods, and perhaps a little ‘fire-water.’”

Entire tribes went to work rendering the oil. William Banfield, the Colonial Secretary’s agent in Barkley Sound, reported in 1858 that in the previous four years the Port San Juan band, the Pacheedaht, living just south of Barkley Sound on the coast and comprising only forty adults, processed between 22,000 and 28,000 litres of dogfish oil per year. By 1874, the Indigenous communities in Barkley Sound alone produced between 91,000 and 114,000 litres of oil. Because it took ten dogfish livers to produce 4.5 litres of oil, this meant catching and processing a quarter of a million dogfish from the immense shoals of these fish along the coast. With multiple hooks, the yield could be as many as 400 in one day. They baited the hooks and tied rocks to the line as weights to catch these bottom-dwelling spiny sharks, ranging from 0.75 metres to two metres in length. According to Robert Brown, the process of extracting oil from the dogfish livers involved a simple apparatus, “merely a box of water into which hot stones are thrown and the oil skimmed off.”

Dogfish oil attracted a growing number of independent traders to venture up the west coast in their small sailing vessels. They would purchase the oil from tribes all along the coast, paying from twenty-five to forty cents for about four litres, and later resell the same quantity of oil to the HBC in Victoria for fifty cents to a dollar. The trade encouraged the establishment of seasonal, and later permanent, trading posts at various locations along the outer coast. Storekeepers at these posts would purchase the oil and collect it in 180-litre wooden barrels, shipping as many as fifteen barrels at a time to Victoria. Decade after decade, this trade continued.

Fred Thornberg managed the trading post at Clayoquot on Stubbs Island from 1874 until 1889; in his memoirs he noted “the Dogfish that in those days swarmed by the millions on the W. coast.” Later, as the trader based at Ahousaht, Thornberg complained bitterly about having to manhandle heavy barrels of dogfish oil in and out of his canoe, often at night and in inclement weather. He would paddle to meet a Victoria-bound schooner or coastal steamer, load the full barrels onto the vessel, and offload empty barrels for future oil purchases. Sometimes in summer the barrels of oil burst in the heat, and on dark and stormy nights the cumbersome barrels occasionally disappeared overboard.

The dogfish oil trade continued well into the twentieth century. Ahousaht elder Peter Webster, in his book As Far as I Know, described how his grandmother processed the oil when he was a child in the 1910s. “She would cut off the heads and tails and remove their livers…The remainder of the dogfish was placed in a big brass pot and boiled.” After boiling,

In the early years of the dogfish oil trade, the lot of the independent trader on the coast proved lonely, precarious, and at times dangerous. In 1854 a Maltese trader named Barney, employed by William Banfield and Peter Francis at their Kyuquot trading post, had amassed 13,600 litres of dogfish oil. He needed the company schooner to come and collect the oil, but he decided not to wait for Peter Francis, who was likely on one of his drinking sprees in Victoria. Barney left the oil with trustworthy Kyuquot chief Ca-ca-hammes and headed south with a number of Kyuquots to confer with Banfield, then in charge of the seasonal trading post at Clayoquot. Neither he nor his companions were seen alive again. Three weeks later, alarmed by rumours of Barney’s murder, Banfield sent Francis up to Kyuquot in the San Diego. Upon arriving, Francis strongly suspected Chief Ca-ca-hammes of murdering Barney for the dogfish oil, which the chief refused to hand over. Protesting that Barney had told him to keep it until his safe return, the chief volunteered to go with Francis to Victoria to clear his name in front of Governor Douglas.

On the return journey to Victoria, the San Diego stopped at Clayoquot, where Tla-o-qui-aht warriors surrounded the ship in their canoes, demanding Francis hand over the enemy Kyuquot chief. Fearing for his life, the chief escaped under cover of darkness, hoping to find his way back to Kyuquot, but the Tla-o-qui-ahts pursued him. After killing and decapitating him, they headed north to attack the unsuspecting and leaderless Kyuquot. They killed thirty of them before being routed. Two years later, Banfield and Francis sailed into Kyuquot to retrieve their dogfish oil only to find that the chief’s son had sold it to rival traders Hugh McKay and William Spring.

In March 1863, word reached Victoria that the schooner Trader, owned by Hugh McKay, had been attacked at Yuquot in Nootka Sound. The captain and a young Tla-o-qui-aht crewman had been murdered. The perpetrators punctured all of the dogfish oil barrels and chopped the Trader into pieces to make it seem she had been lost in a storm, then distributed items of value from the ship among their tribe. When the Tla-o-qui-ahts learned their tribesman had been killed by the Mowachahts, they prepared an attack to avenge the loss. In September, the naval gunboat HMS Cameleon visited Nootka but did not find enough concrete evidence to arrest anyone for the crime. Nevertheless, Captain Edward Hardinge ordered his crew to put on a display of firepower, using the ship’s cannons to “give a foretaste of what they were to expect,” according to the British Colonist on September 21, 1863.

Elsewhere on Vancouver Island, over a decade before the loss of the Trader, naval gunboats had responded vigorously to another inflammatory incident. In 1849 the Hudson’s Bay Company started a small coal-mining operation on the northeast coast of Vancouver Island at Fort Rupert (Port Hardy) amid what visiting naturalist John Keast Lord described as “a sea of savagery.” Three HBC sailors, hoping to make their fortunes on the goldfields, had deserted their posts on the company barque Norman Morison, escaping from Victoria aboard the England, which headed toward Fort Rupert. The three men were murdered by the Newitty band of the Kwakwaka’wakw, apparently because the Newitty believed the deserters were wanted “dead or alive.” The newly appointed governor of the Colony of Vancouver Island, Richard Blanshard, decided to mete out his form of justice, following an initial investigation by the HBC’s surgeon, Dr. John Helmcken, who also served as a magistrate. Blanshard sailed north in the Royal Navy corvette Daedalus, with a crew of sixty, to confront the Newitty, and he demanded the suspected murderers be handed over. The chief refused, whereupon Blanshard ordered the crew of the Daedalus to destroy two nearby Newitty villages, standing vacant at the time. The following year Blanshard returned in the sloop Daphne, once again trying to apprehend the suspects. This time the Newitty fired shots at a party of sailors, wounding some of them. Blanshard then ordered the Daphne’s crew to destroy yet more villages. This action led to the Newitty turning over three dead bodies, reputedly those of the murderers, thus ending “this miserable affair,” as Dr. Helmcken described the episode.

Blanshard’s actions at Fort Rupert marked the first time the colonial authorities used gunboat diplomacy—or lack of diplomacy—to deal with Indigenous people on Vancouver Island. It was not the last. Summing up the situation, the 1901 Year Book of British Columbia says of the First Nations along the coast that “they had ever in their hearts the wholesome dread of a Hudson’s Bay Company gun-boat or man-of-war.” Richard Blanshard’s eighteen-month tenure at Fort Victoria as governor of the colony ended with him leaving in disgust, returning to England in September 1851. He had loathed life in the colony and did considerable harm, seeing it as his duty to “repress and over-awe the natives.” As chief factor of the HBC at Victoria, James Douglas argued against Blanshard’s high-handed actions, maintaining that “it is expedient and unjust to hold tribes responsible for the acts of individuals.” Yet even with his more enlightened attitude, when he succeeded Blanshard as governor, Douglas found himself deploying gunships to quell trouble with coastal tribes.

On November 5, 1852, two Indigenous men murdered Peter Brown, a Scottish shepherd working for the Hudson’s Bay Company at Lake Hill, eight kilometres from Fort Victoria. Surmising that the culprits had fled to Cowichan, Governor Douglas set off in January 1853 with a force of 150 naval crew and Royal Marines. They travelled aboard the frigate HMS Thetis and the HBC’s brig Recovery, towed by the HBC paddlewheeler Beaver to ensure safe passage through the uncharted and narrow waterways off southeastern Vancouver Island. Surrounded by the armed sailors and marines, and under the protection of the ships’ guns, Douglas met with 200 Cowichans at the mouth of the Cowichan River and negotiated the surrender of one of the suspects. Hearing that the other suspect had fled north, Douglas and his force later apprehended the second man, a member of the Snuneymuxw band, near Nanaimo. After a trial on the deck of the Beaver in Nanaimo Harbour in front of a jury made up entirely of naval officers, and with all of the Snuneymuxw in attendance to witness the event, the authorities hanged the two condemned men at Gallows Point on Protection Island. Douglas described his handling of this event as “a fist of iron in a glove of velvet.”

The attempted murder of British subject Thomas Williams in 1856 in the Cowichan Valley provoked another strong response from Douglas. With the Crimean War over and more Royal Navy ships and men at his disposal, Douglas dispatched a force of over 400 aboard HMS Trincomalee (twenty-six guns), towed by the HBC steamer Otter, to the mouth of the Cowichan River. This time the massive show of force produced a suspect, whom the authorities tried, found guilty, and executed in front of his assembled Cowichan people the following day.

In January 1859, the American brig Swiss Boy, outward bound and loaded with lumber from Port Orchard in Washington State, sprang a leak and put in to Barkley Sound. The master beached the vessel in order to make repairs, only to be boarded by hundreds of Huu-ay-ahts. They sawed off the main mast, pillaged the vessel, and robbed the crew of nine, but did them no other harm. Coastal trader Hugh McKay, passing in his Morning Star, conveyed the captain and crew to Victoria. Governor Douglas sent the twenty-one-gun, steam-powered corvette HMS Satellite to investigate. Captain Prevost convened an inquiry, attended by the Huu-ay-aht chiefs, on the deck of his ship. The Huu-ay-ahts readily admitted their actions, claiming they had boarded a foreign ship in “King George’s” waters, expecting commendation, not censure. Taken aback, Prevost took one chief to Victoria with him and reported to Douglas that auger test samples showed the hull and mast of Swiss Boy had rotted throughout, and that Swiss Boy should never have been at sea in the first place. In the end, another ship recovered the cargo of lumber, and the chief who had been taken to Victoria returned home after a few weeks.

Incongruously, two energetic Englishmen in search of adventure showed up on the west coast at this juncture. Classic adventure-seekers of the Victorian age, these men proved themselves cheerfully oblivious to the risks on the coast, and like other eccentric explorers of the era they arrived in territory entirely unknown to them with an unlikely aim. They wished to circumnavigate Vancouver Island—apparently just for the fun of it. Captain Charles Edward Barrett-Lennard, a Crimean cavalry veteran, and Captain Napoleon Fitzstubbs—whose name often appears as Fitz Stubbs—arrived in Victoria in 1860 aboard the Athelstan. As deck cargo, the two brought with them Barrett-Lennard’s twenty-ton cutter Templar, which he had sailed in British waters as a member of the Royal Thames Yacht Club. Barrett-Lennard also brought his dogs; one a purebred bulldog.

The two set off aboard the Templar in the autumn of 1860 “to re-create,” as the British Colonist put it. This recreation took them on a two-and-a-half-month voyage around Vancouver Island. Flying the blue burgee of the Royal Thames Yacht Club, and wearing the club’s brass-buttoned jacket, Barrett-Lennard appeared to be a high-ranking officer in the eyes of the First Nations chiefs he visited. His bulldog also made quite an impression; at Yuquot the local chief offered to exchange one of his own dogs, “a vile mongrel,” for the bulldog. Barrett-Lennard instead offered the chief a pair of his own trousers, which the chief did not care for, despite the trousers “having been cut by Hill, of Bond Street.” In Clayoquot Sound, the two Englishmen marvelled at the size of the timbers supporting the big houses they visited in the villages, estimating the timbers to be a hundred feet long by three or four feet in diameter (30.5 metres by 1 metre), and baffled by how “these savages” could raise such beams. “The sight of these buildings,” Barrett-Lennard wrote in his colourful account of their travels, “produced the same effect of wonder on my mind as did the first visit to Stonehenge.”

Following their adventure, they sailed the Templar to Clayoquot where they briefly took over the trading post. “Trading for oil and furs with the Indian offers a remunerative field for energetic men with small capital,” commented the British Colonist approvingly. After he returned to Britain in 1862, Barrett-Lennard published an account of their cruise, Travels in British Columbia: With a Narrative of a Yacht Voyage Around Vancouver’s Island. He later became a baronet following the death of his father. Before leaving Victoria, Barrett-Lennard sold the Templar to Robert Burnaby; it foundered in 1862 in a southeast gale off Foul Bay. Fitzstubbs stayed on in British Columbia, serving as government agent, stipendiary magistrate, and gold commissioner at Hazelton and later at Nelson. Their names, and that of their boat, are commemorated in Clayoquot Sound: Stubbs and Lennard Islands and Templar Channel.

These various traders and early settlers on the west coast all lived a risky existence. On October 20, 1862, William Banfield lost his life. First reports claimed he had drowned while going out in his canoe to meet the schooner Alberni, but later the British Colonist reported that he had been killed on shore. A wave of alarm ran along the coast following Banfield’s death, and the naval vessel Devastation headed out to investigate. Authorities charged a Huu-ay-aht named Klatsmick with the murder, but after being tried in Victoria, he was acquitted. On his return to Barkley Sound, Klatsmick boasted of killing Banfield. Rumours about the murder continued to circulate on the coast for a long time. As the Colonial Secretary’s agent at Barkley Sound, and well known as a coastal trader, Banfield had lived for many years on Vancouver Island. He arrived at Fort Victoria in 1844 as a ship’s carpenter aboard HMS Constance and soon realized the area’s potential for trading when he sailed off the coast with the Royal Navy. Upon his discharge in 1849, he began trading at various locations, including Clayoquot, in partnership with Captain Peter Francis and Thomas Laughton. He wrote a series of articles about the Barkley Sound area for the Daily Victoria Gazette in 1858 and moved to live there permanently in 1859.

In August of 1864, Captain James Stevenson anchored his sixteen-ton trading vessel Kingfisher at Matilda Creek, Flores Island, in the heart of Ahousaht territory. The previous year Stevenson had been convicted and fined $500 at New Westminster for selling liquor to Indigenous people. Accounts vary concerning what occurred next at Matilda Creek, but unquestionably the Kingfisher incident and its aftermath represent the most aggressive gunboat action on the West Coast.

The Ahousaht chief Cap-chah may have told Stevenson he had dog-fish oil to sell and then, possibly due to alcohol-related incidents and the abduction of local women by the traders, the Ahousahts’ anger ignited. Chief Cap-chah and twelve Ahousahts attacked and killed Stevenson and his two-man crew, a European named Wilson and an Indigenous man from Fort Rupert. Weighting the bodies with stones, they sank them in the sea and afterward plundered, set fire to, and scuttled the Kingfisher. On September 10, 1864, when word of the incident reached Victoria, the British Colonist declared: “It behooves the government to institute prompt enquiries into this matter, and if the outrage has been committed as represented to inflict prompt punishment. The tribes involved had their habitation on the sea coast and can, therefore, be reached at all times by a ship of war. It has been for some time the boast of the Indians on the west coast that murders have been committed by their tribes without any attempt at retribution.”

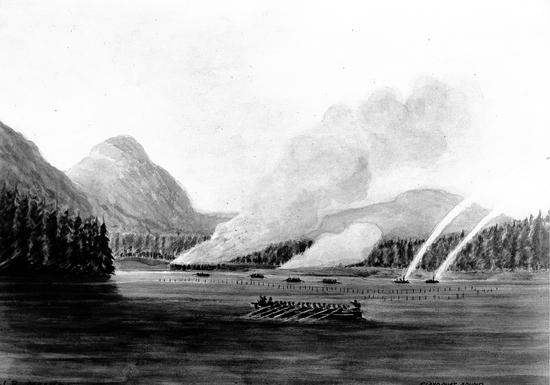

With the pressure of public opinion mounting, in late September 1864 Rear Admiral Joseph Denman sent the gunboat HMS Devastation to Clayoquot Sound, under the command of Captain J.W. Pike, to demand the murderers be given up. Finding Matilda Creek deserted, Pike headed to Herbert Inlet, where “a large body of Indians in their fighting paint fired upon the boat and ship,” according to Denman’s account. Pike retreated to report to Denman, and in short order he returned to the area on the Devastation, this time accompanied by the Sutlej, commanded by Admiral Denman himself. Denman’s wife accompanied her husband aboard the Sutlej. They found the Ahousahts still defiant, refusing to surrender any of the suspects.

The two vessels opened fire, systematically destroying villages and encampments in several locations over several days. In all, the Sutlej and Devastation shelled nine Ahousaht settlements in Herbert Inlet, Shelter Inlet, and elsewhere. Still the Ahousahts refused to co-operate. A lengthy attempt to negotiate through an interpreter led to Denman receiving “a message from the Indians saying that if I wanted the men I might come and take them, if I destroyed the village they would soon build it up again and if I attempted to touch the canoes they would shoot every man who came near the shore. I then ordered heavy fire to be opened on the village.” To ensure the complete destruction of this village, Denman sent boats ashore to set the place alight. Feeling “obliged to strike a yet more severe blow,” Denman then ordered an attack over land. “On the morning of the 7th October, forty seamen and thirty marines (with seven Indigenous guides) were landed at White Pine Cove in Herbert Inlet…[and] ordered to march across the trail to Trout River…to seize Cap-chah and any of his people.” Taken by surprise, the Ahousahts attempted to fire back at their heavily armed attackers, but in the end they fled. At least ten of their people lay dead. Chief Cap-chah, although wounded, managed to escape.

In all, the firepower let loose by the gunboats and the land attack killed fifteen Ahousahts, said to include three of the culprits, and destroyed scores of canoes. The Navy took eleven prisoners, including Chief Cap-chah’s wife and child as hostages, and five large war canoes to Victoria. In his official dispatch to Governor Arthur Kennedy, Denman wrote: “It is with great pleasure that I inform you that the service in which 69 canoes have been destroyed and about 15 men killed, has been performed with the slightest injury on our side.”

When the Ahousahts who stood accused of murdering the crew of the Kingfisher were tried in the Supreme Court in Victoria, Chief Justice David Cameron acquitted them on the grounds that he could not accept evidence from non-Christians: “These people do not believe in the existence of a Supreme Being and therefore they are not competent to take an oath.” This prompted Rear Admiral Phipps Hornby to pronounce, “From the refusal to admit Indian testimony, it follows that as long as the Natives, in attacks upon British traders, take care to leave no survivors to give evidence they are secure from conviction and punishment in the Supreme Court at Victoria.”

Many years after the event, in 1910, the British Colonist ran an article by J. Gordon Smith, retelling a story he had heard from a prospector of how the Kingfisher came into Clayoquot Sound. The article provides an eyewitness account of the destruction of one of the Ahousaht villages, told to the prospector by a man named Skundo, who acted as pilot aboard one of the gunships. His people blamed Skundo for having guided the gunship to this village and banished him. The man had been living alone as an outcast for twenty years when he met the prospector.

On October 17, 1864, the British Colonist stated that the shelling of the Ahousaht villages had been “conducted according to the strict rules of civilized warfare.” Many would dispute that. “This was not a war,” declared Ahousaht hereditary chief Earl Maquinna George in his 2003 book Living on the Edge. “We consider it punishment for the Ahousaht Nation…According to our history they killed over 100 people…They wrecked the houses and canoes and took as hostage a chief, or Ha’wiih youngster, called Keitlah Mukum.” Nonetheless, according to Father Augustin Brabant, the Roman Catholic missionary who lived on the west coast for nearly thirty years in the late nineteenth century, some Ahousahts came to view the Kingfisher episode with a degree of pride. “They had not given up their chief to the white man: they had lost houses, canoes and iktas [things], but these they could and would build again; some of their number were taken prisoner, but were afterwards returned to them…therefore they claimed a big victory over the man-of-war and big guns.”

The Kingfisher incident and its aftermath attracted international attention. A lengthy and detailed article appeared on December 31, 1864, in the pages of the Illustrated London News, complete with drawings by Lieutenant Edward Hall of the Sutlej. Entitled “Conflict with the Indians of Vancouver Island,” the article ends by reproaching the action of the gunboats. “The frequency of outrages and disorders on this coast,” it states, “is a subject of the more regret, as it is notorious that the white man himself is often to blame when the Indian takes the law into his own hands. The appointment of a government agent, a man of character and intelligence, well acquainted with the Indian language and customs, to whom they might appeal in disputed cases would perhaps obviate the necessity for any hostile action in future.”

A particularly strange twist of fate arising from the Kingfisher incident involved a very young child. Mrs. Denman, the admiral’s wife, decided to adopt a little Indigenous girl, possibly an orphan, who had been brought aboard the Sutlej during the hostilities. She named the child Maggie Sutlej and dressed her in the latest fashions. The crew of the Sutlej made much of the child, spoiling her outrageously. The little girl lived less than two years after being taken from Clayoquot Sound. She died aboard the Sutlej as it sailed off South America. Her name appears on a memorial marker erected to commemorate crew members of the Sutlej who died while serving on the vessel. The marker still stands in the Old Burying Ground in Pioneer Square in Victoria, where the inscription recalls “The Little Indian Girl Maggie Sutlej who was Captured During the Indian Outbreak on the West Coast in 1864…who Afterwards Died at Sea.”

What the Illustrated London News termed the “outrages and disorders” of gunboat diplomacy did not end with the Kingfisher. Five years later the shipwreck of the John Bright near Hesquiaht proved to be not only a maritime tragedy, but also a tragedy of Victorian attitudes and of relations between Europeans and Indigenous people. In February 1869 the John Bright, a 126-foot (38.5-metre) barque with twenty years of worldwide lumber trading, set sail from Port Gamble in Puget Sound, bound for Valparaíso, Chile. Captain Burgess had charge of the ship, accompanied by his Chilean wife and children, as well as an English nursemaid, seventeen-year-old Beatrice Holden. Once clear of Puget Sound, the ship found itself in the teeth of a vicious winter gale. The ship rode with the southeast wind, struggling to stay offshore, but the storm bore the John Bright too close to land. She struck at Hesquiaht Peninsula, near Estevan Point, about three kilometres from Hesquiaht village. No one survived, and news of the wreck did not reach Victoria until early March, when sealing captain James Christensen brought a sensational story to government officials and to the newspapers.

Christensen, whose previous trading along the coast had earned him an unsavoury reputation, reported that because some of the bodies had been found disfigured and above the tide line, and since some Hesquiahts were seen wearing clothes belonging to some of the victims, foul play looked likely. He also reported that he had purchased three rings from the Hesquiaht, which he believed had been stripped from the victims. British Colonist newspaper owner and columnist David William Higgins took up the story. He concluded his article of March 16: “All have undeniably found either a watery grave, or have fallen by the hands of the West Coast savages.” Governor Frederick Seymour, a long-serving colonial administrator, took a more skeptical view and hesitated to send warships to the area.

Wild speculation based on very little sound evidence continued, fed by Christensen and Higgins, blowing the story out of all proportion. By April 23 the headline in the British Colonist read: “Six more bodies of the Bark John Bright found with their heads cut off? They were without doubt murdered by the Indians.” Then followed more of Higgins’s speculative hyperbole: “It was shown that the captain had been shot through the back while in the act of running away in the vain hope of escaping from the cruel savages, who had proved themselves to be less merciful than the wild waves. The other prisoners were thrown down and their heads removed while they piteously begged for mercy.” As for the nursemaid, Beatrice Holden: “The pretty English maid was delivered up to the young men of the tribe, who dragged her into the bush. Her cries filled the air for hours, and when she was seen again by one of the native witnesses some hours later, the poor girl was dead, and her head had disappeared.” On April 26, Higgins castigated Governor Seymour for his inaction: “Gov. Seymour has allowed the British flag to be insulted and trampled by the savages of the West Coast…We are exposed to the attacks of savages, who are allowed to rob and murder white men trading upcoast, with impunity.”

Forced into action, Seymour sent the steam-driven HMS Sparrowhawk north from Victoria on May 1, bound for Hesquiaht. Her mission: to investigate the sinking of the John Bright and subsequent events, nearly three months after the shipwreck. On board were a group of Royal Marines; Henry Pellew Crease, the Attorney General of BC; the Honourable Henry Maynard Ball, magistrate of Cariboo West; as well as Captain James Christensen, who had advanced the story of massacre, to act as interpreter. When his ship arrived off Hesquiaht village, Sparrowhawk’s commander, Henry Wentworth Mist, noted in his log that despite the strong military force the locals “seemed utterly unconcerned with our arrival, or at the landing of so large a force.”

Surgeon-Lieutenant Peter Comrie supervised the exhumation of the eleven bodies, buried by Christensen on his second visit to Hesquiaht following the sinking. After examining the remains, and after summoning witnesses, a coroner’s inquest began on board the Sparrowhawk. The inquest continued for three days, and in his testimony Dr. Comrie asserted that “he could find no medical evidence that indicated that the bodies had been decapitated by human hands.” In the medical journal of the Sparrowhawk, Comrie wrote that “he believed that the gnawing of wild animals and the terrible pounding of the bodies in the surf on that rocky coast sufficiently accounted for their mutilated conditions.” Despite this testimony, the inquest ruled that murder had indeed taken place and demanded the Hesquiaht chiefs turn over the perpetrators. They failed to do so, perhaps not knowing who to produce, and Commander Mist ordered the Royal Marines to set fire to the village houses, and to fire salvoes from the Sparrowhawk’s cannons into the canoes drawn up on the foreshore. That done, Commander Mist ordered seven Hesquiahts—five witnesses and two accused—seized and taken aboard the Sparrowhawk to be bound over for trial in Victoria.

In Victoria, in proceedings that by today’s standards would be declared a mistrial, the two accused, Katkinna and John Anietsachist, had little chance of acquittal. Higgins kept up his relentless stream of alarmist reporting in the British Colonist, so the people of Victoria wanted nothing less than for the jury to find the two men guilty and hang them. With James Christensen acting as Chinook interpreter and his friend Gwiar, a Tla-o-qui-aht chief who had no love for the Hesquiaht, acting as Nuu-chah-nulth interpreter, the two accused—without legal representation—faced a twenty-man, all-white jury. In the middle of the first trial, of Katkinna, the judge ordered a recess for a week for the funeral of Governor Seymour, and further postponed the trial while awaiting the return of Surgeon-Lieutenant Comrie, who was away on duty. During these adjournments the jury roamed Victoria and talked to the press. The British Colonist even published a letter from Robert Burnaby, foreman of the jury, who took the government to task for its inaction and mentioned the “praiseworthy conduct” of Captain Christensen. In the end, with Christensen acting not only as interpreter but also as a witness, Katkinna admitted: “I shot the man, as he was coming ashore from the wreck.” Condemned from his own mouth, the jury found him guilty.

In the second trial, John Anietsachist stood accused of the murder of Beatrice Holden. Despite assertions from Surgeon-Lieutenant Comrie that the injuries to the body were “very likely to have occurred from a fall on the boulders or having washed backwards and forwards against the boulders by the tide,” and relying heavily on interpreted statements from the five Hesquiaht witnesses, the jury took only five minutes to find Anietsachist guilty.

With both men sentenced to be hanged, the authorities placed them in irons aboard the Sparrowhawk, which steamed back to Hesquiaht carrying the High Sheriff of Victoria, fifteen police constables, twenty Royal Marines, and a few carpenters, as well as the prisoners. Ironically, the Sparrowhawk nearly ran aground in fog at the location where the John Bright had foundered. Once the gunship reached Hesquiaht, the carpenters, protected by Royal Marines, set about building gallows on the shore.

Father Charles Seghers, a parish priest in Victoria, also travelled aboard the Sparrowhawk, his task being to accompany the two condemned men and to proffer Christian comfort. Originally from Belgium, Seghers had been in Victoria since 1863 and had long yearned to work as a missionary on the west coast, but the bishop of Victoria, Modeste Demers, believed the priest’s health to be too frail to take on such work. Until this highly charged trip to Hesquiaht, Seghers had never seen the vast terra incognita of Vancouver Island’s west coast, an area he believed to be peopled with savage tribes in desperate need of Roman Catholic missionaries.

Having done his best to console the two condemned men, Seghers baptized them both. The entire Hesquiaht tribe stood, perplexed and fearful, in front of the gallows to witness what ensued. As the cannons of the Sparrowhawk boomed out, the two men were hanged. Deeply affected by everything he witnessed, Seghers found this trip up the coast to be a decisive turning point in his life. “Then and there,” according to Father Maurus Snyder, a later missionary on the coast, “[Seghers] resolved to return soon…that he might bring the blessings of Christianity to the benighted natives.”

Five years later, Seghers did indeed return to the Hesquiaht, bringing with him Father Augustin Brabant. When the two men arrived in the spring of 1874, the gallows on which the accused men had been hanged still stood on the shore, a reminder to the local people of the nature of British justice, and an example of the outrages and disorders afflicting the coast.