Chapter 20: Adjustment

The spike in demand for herring roe took Tofino by storm in 1971. Highly valued in Japan for kazunoko, a traditional dish symbolizing fertility and family prosperity, roe became the most valuable commodity on the west coast following the depletion of herring stocks in both Japanese and Russian waters, driving a fishing extravaganza even wilder than the pilchard boom in the 1920s and ’30s. Hundreds of seiners, gillnetters, and herring skiffs arrived in Clayoquot Sound that spring, looking to scoop up as many herring (Clupea pallasii) as their boats could hold, while fish buyers vied for their catches with suitcases full of cash. “It was like the Wild West on water,” commented a witness.

When herring spawn in coastal waters in late February and early March, the female herring, each carrying 20,000 to 40,000 eggs, swim into bays and inlets at high tide and deposit their roe on the kelp and eelgrass near the shore. The male herring turn the water milky white as they deposit their milt on the roe. Seabirds fly about in a feeding frenzy, sea lions and seals gorge themselves on herring until they can eat no more. Every season is different, every spawn is different, but in the 1970s the herring consistently flocked in, demand soared, and the roe industry boomed.

Fishermen have only a matter of hours to capture the female herring before they deposit their roe. Because timing is so critical and the window of opportunity so small, boats would stand by in great numbers, awaiting permission from the Department of Fisheries to begin netting the fish. In the rush for herring roe, this led to chaotic fishing in very tight quarters that sometimes saw boats ramming each other while jockeying for the best locations to set their nets. Fish companies chartered float planes to scout for herring from the air. Doug Banks became the first pilot to install a sounder on his plane, so if he landed amid a school of herring, he could report the extent and number of fish. “We radioed our reports in code, so other planes and the fish boats wouldn’t understand. Soon everyone was doing the same. It was cutthroat competition,” Doug recalled. Occasional fist fights broke out, and fishermen threatened each other with guns, for fortunes could be lost if a boat and its crew failed to catch as many fish as possible in the allotted time. Those lucky enough filled their holds and even their decks to overflowing; in 1975, ten overloaded boats went down on the west coast in the unpredictable March weather.

Fish packers cruised the fleet in the boom years of the 1970s, offering astronomical amounts of money to fishermen. “Japanese fish buyers skulked around town in business suits, carrying briefcases full of fifties,” wrote Andrew Struthers. “‘Just a gift,’ they would say. ‘Please remember us when you catch some herring.’” One fisherman recalled a fish buyer paying him with 341 thousand-dollar bills from a briefcase that held $1.25 million in cash. Asked to carry a paper bag from a float plane to a boat, a local woman obliged, unaware until later that she had held over $300,000 in cash. One boat made $1.6 million in one set, according to Walter Guppy, and fisherman Frank Rae-Arthur maintained that with so much cash circulating on the coast, no hundred-dollar bills could be found east of Winnipeg. Ladies of the evening arrived from Vancouver and set out for the fishing grounds in the Marabel and other yachts; some women reportedly accepted payment in herring roe if the men had no bills small enough.

While the United States allowed frozen whole herring to be shipped to Japan for processing, Canadian law demanded that the herring roe be processed in Canada. In 1972 this led Bob Wingen into partnership with Andrew Tulloch and Ned Easton, to expand his involvement in the fishing industry. Wingen had taken over the family business in 1955, renaming it Tofino Marine Services. The Wingens’ days of boatbuilding had come to an end, and Bob’s interests diversified to include fish packing for various companies, harvesting and processing oysters, and managing fish-buying camps on the west coast of Vancouver Island. With the herring boom in full swing, and confidently expecting a $1.7-million grant from the federal government as part of an initiative to employ aboriginal workers, Wingen and his partners borrowed money in 1972 to develop new facilities. The first stage of the new operation, now called Tofino Fisheries Ltd., started up in 1973, processing herring, groundfish, oysters, and shrimp. By 1974 the second phase had been completed, replacing the machine shop and boat shed with a reduction plant, freezer, and cold storage. By then the operation stood out as the largest enterprise in town, employing 240 workers, including 125 Indigenous workers. However, changes in the federal government radically affected the financing of the operation, with the result that the company received only $319,000, instead of the expected $1.7 million, forcing it into receivership. Canadian Fishing Company took over Tofino Fisheries that year, selling it to BC Packers in 1980.

During the herring boom, the plant hired hundreds of workers to handle the catch, process the herring roe, and render the herring into fishmeal. “The plant hummed around the clock and there was overtime galore,” according to local writer Frank Harper, who worked there, wearing two of the mandatory hairnets (one on his beard). In The Sound magazine, Harper described the all-important fish line, where only women worked, popping the “jewelled roe” out of the swollen bellies of the female herring. “Squeeze, pop, squeeze, for 10, 12 hours a shift, the ladies sometimes singing songs in time with the great grating machinery to break the monotony…as many as 80 women crowded in at the long table, elbow-to-elbow, popping, singing.” The roe, stored in airtight containers, was airlifted to Japan; the rest of the herring rendered down and shipped out of town.

According to Harper, Tofino’s population tripled in springtime during the years of the roe fishery. “Fishermen and migrants swarmed here in all sorts of weird vehicles: rickety homemade houses on wheels with stovepipes poking through the roofs, and in hippie busses painted psychedelic, trucks pulling skiffs stacked three high.” Tofino’s St. Francis of Assisi Roman Catholic church on Main Street opened its doors to a group of Ahousaht women who worked in the fish plant, allowing them to sleep and stay in the church so they would not have to travel back and forth.

“The whole town reeked of money and herring,” as Jacqui Hansen put it. “Everyone complained about the fishy smell, but to me it was the smell of money because my kids were working in the fish plant making fifteen dollars an hour, huge money at the time. We had herring scales over everything; they stuck to the skin; they stuck to the shower, they got inside the washing machine and attached to clothes. They were everywhere.” Janis McDougall’s essay in Writing the West Coast describes how she recognized fish plant workers “by the flash of silver scales on their clothes and by the invisible cloud of odour that remained in the bank long after paycheques had been cashed.”

With so much money floating around, the bars in Tofino did a booming trade as groups of people gathered to spend some of their cash and wait for the next herring opening. “We lived in herring then…,” Frank Harper wrote. “It was a rush, a chore, a thrill, a drag, a bonanza.” Even the bears were happy. On one occasion a truck carrying a load of herring meal tipped over on its way out of town, spilling its load. The bears feasted royally.

The herring roe fishing frenzy lasted only a few years, with prices rising from $60 a ton to $5,000 a ton before Japanese consumers balked at paying $26 per pound in their stores. By 1980 the bottom fell out of the market, leaving prices at $9 per pound. Some Japanese companies, having stockpiled tons of US frozen herring, went broke, and on the west coast many BC fishermen rued the downturn. One fisherman summed the whole herring episode up: “It was very intense. It could be very, very dangerous but, boy, it was super exciting. I don’t think you’ll ever see another fishery like that again.”

The herring boom gave the village of Tofino a small taste of what it meant for the town to be overtaken by a new industry and assailed by an influx of new people. The town had been facing constant adjustments since the creation of the road; by the mid-1970s, the days of living in tranquil obscurity as an isolated fishing village seemed like a distant dream. The park had come to stay, the long beaches were becoming widely known, the youth culture of the beaches continued to influence the town, and the numbers of visitors kept increasing. In Tofino village the first wave of small motels and resorts appeared from the mid-1960s to the early 1970s: Duffin Cove Cabins, Lone Cone Motel, Esowista Place Motel, the Mini Motel, and the Apoloma Motel (later the Pacific Breeze). Available tourist accommodation in the village faced a temporary reduction in the summer of 1973 when fire destroyed part of the Maquinna Hotel. Originally owned by Reuben Parker, Frank Bull, and Dennis Singleton, the Maquinna had opened on July 1, 1959, built with material salvaged from the Tofino air base. Initially, the hotel housed a grocery store on its lower floor facing Main Street, with the beer parlour on the main floor. By the time of the fire, the hotel had a dining room, lounge, and cabaret; the beer parlour, with its separate entrances for “Men” and “Ladies and Escorts,” then occupied the ground floor. The fire destroyed the cabaret and caused considerable water damage. All forty-five guests had to be evacuated, but the main part of the building remained intact thanks to Tofino’s volunteer firefighters. For a short while the hotel closed, but the beer continued to flow.

Out at MacKenzie Beach, the MacKenzie family expanded their campsite, by 1972 offering twelve cabins and a mobile home park to visitors, plus several cottages to rent. Farther along MacKenzie Beach, Ben Hellesen, who had earlier operated a fish plant in Tofino, opened Ocean Village Resort in 1976, with its distinctive beehive-style cabins. Hector Bodchen opened Crystal Cove Resort as a small campground in 1979, later building a number of log cabins for guests. At Cox Bay, the Pettinger family acquired their resort in 1973. Having spotted an advertisement in the Edmonton Journal, they bought 16.5 hectares of oceanfront in Cox Bay where the Pacific Paradise Motel stood, a lodge built several years earlier with recycled materials from the airport. The Pettingers renamed their venture the Pacific Sands Beach Resort; now much expanded, it remains the longest-running resort in the area.

While all these new facilities provided more accommodation in the area, other local amenities remained scant. Maureen Fraser arrived on the west coast in 1975, after driving across Canada and visiting both Banff and Jasper National Parks en route. She had enjoyed the amenities the towns of Banff and Jasper offered to park visitors, and she arrived at Pacific Rim National Park expecting at least some services for visitors. Out near the park, she found nothing. All services at Long Beach had disappeared by then: the little stores and the gas stations had gone, along with the Fiddle-In Drive-In that had once boasted “The Finest in Fish ’n’ Fountain,” serving “Hamburgers, Abalone Burgers, Oyster burgers, Prawn burgers.” Maureen went to Tofino in search of a cinnamon bun: “I couldn’t find one because there was no bakery in Tofino. Nothing. I looked around and thought, ‘This town doesn’t know what’s hit it.’ Pacific Rim National Park has just been created right next to it, and it had this amazing Sound, and it had almost no services. No bakery. No bookstore. No place to rent canoes and kayaks.” Maureen continued on her planned road trip down to South America, noting how tourist centres catered to their visitors, and developing ideas of what she would do. A year later she returned to Tofino to start a business that has become arguably the town’s most notable gathering place, the Common Loaf Bakery and Café, famed for its bread and cinnamon buns, and for its freewheeling community notice board.

In the mid-1970s, deciding where to go out in the evening in Tofino was not difficult. The Maquinna Hotel restaurant served dinner, or customers could go there for a drink in the Tiki Cocktail Bar or in the beer parlour. The only other choices were the small Kakawin Café (later the Loft Restaurant) or the Schooner Restaurant. The Schooner occupied the site of Vic’s Coffee Bar, which had first opened in 1949 in a section of a disused RCAF hospital building, moved into town that year by Tofino’s Masonic Lodge. The Masons occupied the top floor, renting out ground floor units to local businesses. In the postwar years, this building stood on the outer edge of the village, backing onto the forest; the Masonic landlords promised their early tenants that one day this would be the centre of Tofino. Vic’s Coffee Bar morphed into the Lone Cone Café before being transformed into the Schooner Restaurant by Jerry Gautier in the early 1960s. In 1968, Gloria Bruce took over the restaurant, making the place famous for its burgers and fish and chips. Still run by the Bruce family, still in its original location, the Schooner carries on a thriving business to this day, now right in the centre of town.

In 1974, the municipal council turned over the town’s Community Hall to a collective of young people as a coffee shop, gathering place, and arts centre. The old hall had been used less and less frequently during the 1960s, for social life in Tofino changed noticeably with the coming of television, which arrived around the same time as the road. Even with only one channel offering fuzzy black-and-white images, the new medium—and Hockey Night in Canada—proved mesmerizing. The Saturday dances no longer exerted their old appeal, and people stayed home more. Re-created as the Gust o’ Wind Arts Centre, the hall took on new life and became the heart and soul of Tofino for many young people who drifted into town and stayed there. Here they gathered to drink coffee, read, pursue their crafts, dance, and listen to live music. Artists and craftspeople leased spaces for around twenty dollars per month where they could create and sell their work from small studios and workshops, and the centre offered classes in different disciplines: music, dance, pottery, carving, yoga, and breadmaking. Well-known carver and photographer Adrian Dorst had a space here; Michael Mullin, now owner of Tofino’s Mermaid Tales Bookstore, shared his collection of books here; Maureen Fraser started her Common Loaf bakery as the Gust o’ Wind Bakeshop. And here, over many cups of coffee, concerned discussions arose about environmental issues, many of them focusing on Meares Island, due to be logged by MacMillan Bloedel. From such discussions, the Save Meares Island group took shape, later evolving into the Friends of Clayoquot Sound. Membership included many of the Gust o’ Wind regulars. While the place attracted mostly young and like-minded people, townsfolk also came in occasionally, some out of curiosity, some to purchase crafts. Dorothy Arnet became a regular customer: “I came for that wonderful bread!”

Not everyone in Tofino approved, many expressed great unease about providing a drop-in centre for a seemingly irresponsible young crowd. The loud music, late-night celebrations, dances, and drumming, along with the wafting scent of marijuana, led to repeated complaints to the town council. In September 1980, council heeded the complaints and closed the centre with a disapproving thud of the gavel, following what the local paper termed “a long and unpleasant feud.” At that time, council could not have foreseen that the 2014 Arts and Culture Master Plan for Tofino would acknowledge the Gust o’ Wind as the town’s first arts society, going on to praise the “free and communicative flair [that] came out of those times that can still be seen within the works of local artists today.”

The closure of the Gust o’ Wind marked the end of an era in Tofino. “Perhaps they thought that if we close the building all these people will go away,” commented Maureen Fraser. Some did leave, but many remained. A new breed of Tofinoite emerged from the counterculture, settling in and near the town to raise families, some buying property; some establishing themselves as small business owners, entrepreneurs, and artists; many becoming actively involved in community affairs and the growing environmental movement. The Community Hall, emptied of its noisy and creative crowd, housed Tofino’s library for a number of years before being demolished in 1997.

The paving of the road, the thriving herring fishery, and the increasing logging activity attracted many new residents to Tofino during the 1970s and ’80s. The town’s population stood at 461 in 1971; by 1991 it increased to 1,103. So many Americans took up residence that an area of town on Olsen Road became known as “Little Seattle.” “Increasingly there were different layers of people in Tofino, and not as much mingling as there had been before,” Leona Taylor noted. In 1972, a twenty-eight-lot subdivision was created on the new Cypre Crescent, largely to house MacMillan Bloedel employees, with lots selling for $2,200. Some of the newcomers became actively involved in local groups, the men coaching local sports teams and running organizations like the Boy Scouts. A few of the women joined the long-established Ladies’ Hospital Aid. Although initially dubious of new members with newfangled ideas—“But we’ve never held a dance at the Legion on Valentine’s Day!”—the older Ladies’ Aid members soon recognized the success of these energetic new fundraisers.

In 1969, Jim Hudnall and his wife, Carolyn, having camped out for three summers in the area, decided to buy property in Tofino. They chose a lot on Tofino Inlet, costing $5,000. “We could have bought land at Chesterman Beach for way less, but no one wanted to live there,” Jim related. “It was too swampy and there was no place for a boat.” At that time, any land for sale at Chesterman Beach belonged to Dr. Howard McDiarmid. In the mid-1960s, he had purchased 490 metres of waterfront property at Chesterman Beach, with an option to buy another 550 metres. Eventually he owned land all along North and South Chesterman Beach, over 120 hectares extending across the Pacific Rim Highway to the inlet. Bit by bit he subdivided sections of this land, initially offering lots for sale for $2,000 each. At first only one sold. Leona Taylor shared the incredulity of most Tofino residents. “Who would buy property way out there? We thought anyone who bought out there was crazy. It was below water level in places and it was way too expensive.”

Slowly, in the late 1960s and early ’70s, lots at Chesterman Beach did begin to sell. Prices crept up. A brochure from late 1971/early 1972 offered lots at Chesterman Beach with 30.5 metres of shoreline for $12,500, and semi-waterfront lots for $4,000. Mary Bewick, among the earliest purchasers, lived there for decades, walking the beach every day. Mary Oliver purchased her land for a dollar down and a promise to pay later, as did Neil and Marilyn Buckle, displaced by Pacific Rim Park from their lodge at Combers’ Beach. The Buckles became the first to build on North Chesterman Beach in 1970, having acquired their waterfront lot for a mere $10,000. According to Charles McDiarmid, “My father gave [Neil] a discount if he would build a house within a year of purchase [because] there were rumours that homes…would sink into the sand at high tide…Neil did build his house and with a basement to boot, to prove that all would be fine…the house he built still stands today.”

By the mid-1980s, some twenty homes, many of them small cabins, dotted the shore along both North and South Chesterman Beach, with a similar number of homes set back from the water along Lynn Road. Neil Buckle milled a good deal of the wood used in these homes at his mill on Vargas Island; he would bring wood over and sell it from his home at Chesterman Beach, operating on an honour system. If no one was at his place to sell the wood, customers simply took what they required and recorded their purchase on slips of paper provided.

Some of the early Chesterman beach dwellers in the 1970s brought with them alternative lifestyles reminiscent of those from Wreck Bay, no doubt surprising the “townies,” who until then had regarded the beach as a local hangout for drag racing up and down the sand. According to Adrienne Mason: “There was ‘Laser Dave,’ who on clear, starry nights, would set out rows of lit candles to show the alignment of the planets (or some say it was a landing strip for aliens). There was the naked carver, Henry. His end of the beach was the nude end. There were the early surfers…There were houses shaped like pyramids and octagons, and those built of salvaged wood by weekend work parties fuelled by beer and clams.”

Increasingly, Chesterman Beach began to attract like-minded families raising young children. A tightly knit community took shape, some of the children home-schooled, many of them taking to the waves on their Boogie Boards and becoming the “beach babies” of Chesterman. The people of Chesterman even initiated their own tsunami warning system, setting up a “phone tree” among themselves. In the mid-1980s, the beach residents formed an association and launched a valiant, although unsuccessful, effort to purchase Frank Island for public use. The island, just offshore and accessible at low tide from Chesterman Beach, would then have cost $48,000. By 2006 the asking price for the island stood at $2.9 million.

At the north end of Chesterman Beach, carver Henry Nolla became an institution on the beach, in the early years walking around nude in the summer, wearing nothing but a bandana and a knife slung around his hips. With quiet, Zen-like concentration, he carved totem poles, bowls, and all manner of other objects in his workshop at the end of the beach known as “Henry’s End.” From time to time he carried out commissioned work, as when the municipality asked him to carve a “Welcome” sign to be placed on the roadside at the entrance to the town. Having grown up in Europe with a Swedish mother and a Spanish father, English served as his third language, and spelling could be problematic. When unveiled, the sign read “Wellcome” and had to be redone.

Described by Andrew Struthers as resembling “Father Time in a Blake engraving,” the much-loved Nolla garnered great respect for his work, acting as a mentor to many other wood carvers. He died in 2004, having lived some thirty years on Chesterman Beach. His work can still be seen all around Tofino: at the Common Loaf Bakery, on the Village Green, and, most prominently, in the distinctive facade of Roy Henry Vickers’s Eagle Aerie Gallery. “I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for Henry,” Vickers once said. Nolla’s large carving shed, adjacent to the Wickaninnish Inn, remains open to visitors and carvers.

If Henry Nolla had walked down to South Chesterman Beach in the late 1980s and early 1990s, he would have noticed the next generation of west coast surfers taking to the sport like ducklings to water. Vern and Gisele Bruhwiler’s children, Raph, Sepp, Francis, and Catherine, and Ralph and Alice DeVries’s son Peter all lived right on Chesterman Beach, as did Kathy Long, Jack and Brian Greig, Amy Henderson and her three siblings, Mike and Ben Campbell, and the Buckle boys, among others. Along with other young enthusiasts, including Jenny and Sarah Hudnall, Sarah Kalkan, Ryan Erickson, Asia Dryden, Seth Amhein, they formed the first generation of homegrown Tofino surfers. They graduated from Boogie Boards to surfboards, and once out there catching the wave, certain members of this group never looked back; they would take west coast surfing to the next level. Because they lived on or near the beach, they could surf before and after school, or in some cases during school hours. “We used to have to go to school by bus,” Sepp Bruhwiler recalled. “Some days Frank and I would purposely miss the bus, sneak back home, grab our gear, go surfing and hang out on the beach all day. Other days if the surf was up mom would allow us to stay home and surf.”

The alternative, slightly offbeat sport of the 1960s and ’70s had changed its image by the time these young surfers were growing up. While still very cool, surfing had become more mainstream, attracting a far more diverse crowd. The popularity of skateboarding and snowboarding, and improvements in wetsuit design, helped, while the California-inspired trendiness of surf clothing and accessories further boosted the sport’s appeal. By the early 1980s, enough surfers had begun haunting the beaches to encourage Liz Zed to start up the first surf shop in the Tofino area; Live to Surf opened in 1984 in an addition she built onto her house at Chesterman Beach. The young surfing crowd vied for the fun summer jobs there.

In 1977, Howard McDiarmid bought the land at the northwest end of Chesterman Beach, including the rocky headland, the area fronting on Shell Beach, and around onto MacKenzie Beach. He built himself a house at the very tip of the headland, employing Don McGinnis—who shortly afterward became Tofino’s mayor—to build the house, with Henry Nolla assisting. Nolla became McDiarmid’s caretaker, living in a cabin nearby. McDiarmid had eyed this property at the headland for many years, dreaming one day he would own it. Having played a leading role in the creation of Pacific Rim National Park, he realized early on the development and tourism potential of the west coast of Vancouver Island, and had long imagined building a resort on this site.

After the original Wickaninnish Inn on Long Beach closed for good in 1977, McDiarmid bought the rights to the Wickaninnish name the day the previous ownership lapsed. His ambition of opening a second Wickaninnish Inn then waited in the wings for many years. By the time the current resort opened in August 1996, Chesterman Beach had been transformed. In the late 1990s, properties hit the million-dollar mark when a Vancouver businessman offered Jim Schwartz a million dollars for his recently completed house on the beach. The new owner later flipped the house for $1.9 million; in 2014 it sold for $2.55 million. The little cabins that once dotted the beachfront fell to sledgehammers or to flames to make way for ever larger, more ambitious homes. Singer Sarah McLachlan bought and built there, also Sunkist CEO Ralph Bodine. These valuable properties on Chesterman Beach, now valued in the millions, rely on services that the early residents never dreamed possible. Many hard-won changes in Tofino’s infrastructure had to occur over the years to enable such development; none more important than the establishment of water and sewer connections to Chesterman Beach in the early 1980s.

From the early days, Tofino residents had generally looked after their own needs in terms of water and garbage disposal. Garbage could be buried but often went straight into the sea, sometimes right off the government wharf, even into the 1960s. For water, people dug wells, tapped into creeks, or simply collected rainwater in barrels. Such water systems could be problematic, as Catharine Whyte mentioned in a letter to her mother in 1943: “The pump water is nice and brown and not very tasty, so we boil it before drinking it.” In 1949, the village voted to create a communal water supply by damming the small creek running into Duffin Cove near Grice Point behind the hospital. The map of Clayoquot Sound made by John Meares in 1778 notes this creek as a “watering place”; Meares and other mariners evidently used it to replenish their ships’ fresh water supplies.

To provide Tofino with water, workers built a forty-five-cubic-metre wooden reservoir near the creek. It fed into a network of water mains painstakingly hand-dug or blasted into the underlying rock throughout the village. Initially, Tofino’s new community water system required someone to make a daily journey to the creek to start the gas-powered generator that pumped water from the creek to the reservoir. When BC Hydro electrical power arrived in the village in 1961, this job became redundant.

Although plagued by a series of misfortunes in subsequent years, for its first few years this water system worked fairly well. Nursed along by Tom Gibson, chairman of the hospital board, later mayor of Tofino, and owner of Gibson Contracting, the water kept flowing. “Tom knew where every pipe in Tofino’s primitive water system was located, and he was always right there to repair the numerous leaks,” Howard McDiarmid wrote. Because Tofino had no sewer system at the time, faulty septic tanks also kept Gibson and his sons busy with ceaseless repair jobs. Sewer connections did not arrive in Tofino until the early 1980s.

Tofino’s water system faced its first crisis in 1958 during a severe summer drought. The lowest rainfall ever recorded in Tofino’s history, only 185 millimetres of rain from May until August, meant most of the rivers in the area dried up, leaving the village with no water. After surviving this ordeal, and with the wooden reservoir by then leaking badly, in 1960 the village built a new forty-five-cubic-metre wooden tank on Meares Island, collecting water from Close Creek. A three-kilometre-long PVC pipe carried the water under Browning Passage to Tofino. Disaster struck in 1964 when the earthquake in Anchorage, Alaska, sent a tsunami surging into Browning Passage. It ripped apart the plastic submarine pipe, depositing pieces of it in crab traps and all over the sea floor. To maintain the needed water supply, a temporary pipe carried water to the village while the original pipe was being repaired and upgraded. Once reinstalled, calamity again intervened. In 1968, unseasonably cold temperatures caused the pipe on Meares Island to freeze and burst, even though water was constantly flowing through it. After repairing the pipe, village officials recognized that the system needed further upgrading because the altitude of the tank at Close Creek provided very limited water pressure; Tofino residents at higher altitudes needed water pumps to ensure they had service. And the submarine pipe continued to pose problems. With new ice and fish plants being constructed on the waterfront, demanding more and more water at a higher pressure, something had to be done.

In 1970, just when Tofino proposed upgrading its water system, Noranda Mines, which had worked the recently closed Brynnor iron ore mine at Maggie Lake south of Tofino, wanted to dispose of a 455-cubic-metre steel tank, free of charge. Seizing the opportunity, the village had the tank cut in half, loaded it onto a flatbed truck, and transported it to Barr Mountain, just behind Tofino village. With the tank welded back together, and with a new and larger submarine pipeline extending from Meares Island to feed the tank, the village’s water pressure shot up from 35 to 126 pounds per square inch.

More adversity hit the water system in November 1975. This time heavy rains sent a mudslide down the side of Mount Colnett on Meares Island, completely washing out the Close Creek dam, the settling tank, and 457 metres of pipe. In April 1976 the Westcoaster described how the town “haywired a workable system together” while lobbying desperately for financial assistance from the province. Finally, with the aid of a $50,000 provincial grant, the village built a dam on Sharp Creek, north of Close Creek, and laid a new pipeline, 4.7 kilometres long, to the village. Just as the forms for the dam had been built and stood ready for the concrete to be poured, a sudden very heavy rainstorm completely wiped out the structure. Workers had to begin the whole building process anew.

With the growing number of residents and visitors, the water requirements of the area increased. The new resorts south of the village, and the expanding community at Chesterman Beach, wanted to be connected to Tofino’s water system. The village council lobbied the federal government for an $11.3-million grant to build an entirely new water system and sewer infrastructure between 1983 and 1986. To expedite the application process and to qualify for the grant, in 1982 the village of Tofino became the District of Tofino, expanding its boundaries to include all the land south on the Esowista Peninsula as far as the northern border of Pacific Rim National Park.

The federal money allowed the District of Tofino to build a water system served by Ginnard Creek, south of Close Creek on Meares Island, and to run a supply line to two large concrete reservoirs, one just south of the village (on District Lot 117), and the other on Lovekin Hill, between Chesterman Beach and Cox Bay. The grant also covered the cost of an infiltration gallery and water settling tank at Close Creek. In 1988, calamity again hit Tofino’s water system. Only three years after it had been constructed, the DL117 concrete reservoir began leaking from the bottom, washing away its sand base. The tank collapsed and was removed from service. To compensate for its loss, in 1992 the District linked #1 Creek on Meares Island into the system. In 1995 a new reinforced concrete base allowed the DL117 reservoir to be put back in service, and Tofino’s water system finally appeared ready to handle the District’s water needs for decades to come.

No matter where one lived in Clayoquot Sound, by 1978 improved medical aid could handle emergencies far more effectively than before. The Tofino Ambulance Service began serving residents of the Sound that year, using an ambulance, planes, and the Tofino lifeboat. The paid employees of the Ambulance Service included about a dozen Tofino townsfolk, including loggers, hippies, fisheries officers, and Co-op workers, headquartered in the old ambulance station behind the hospital. Two remained on call all the time, and the service fielded an average of 200 calls a year. At the hospital, Dr. Harvey Henderson arrived to replace Howard McDiarmid, who left Tofino in 1972. Henderson initiated regular visits to Hot Springs Cove and Ahousaht, flying in to hold local clinics. The nurses’ residence in Tofino had expanded over the years to house half a dozen nurses. The matron, Australian-born Dilys Bruce, ruled her domain with a strict hand. Actively involved in the community, she also co-owned the Mini Motel with Mary MacLeod, and both Dilys and Mary staunchly supported the environmental movement in later years. One of the nurses who served many years at the Tofino hospital, Midori (Sakai) Matley, had survived the bombing of Hiroshima. She and her husband, Peter, became long-time Tofino residents. For years, she was the only Japanese person in town.

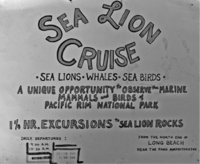

As Tofino worked to improve its infrastructure and services, many in town explored ways of tapping into the economic potential created by visitors. Among the earliest to sense that tourists would pay to see wildlife, Jim and Carolyn Hudnall bought an old survey boat in 1970 and started their Clayoquot Cruise and Charter business. As Carolyn explained, “This was the beginning of the environmental era and we were part of that consciousness, and had become acquainted with some of the scientists who were working to preserve the wild.” Leaving from the crab dock, they gave “sunset cruises” as well as wildlife tours around the islands in Tofino Harbour and up the inlet, viewing birds on the mud flats, eagles, raccoons, and seals. No one thought, at that point, of whale or bear watching. Sea lions, though, already had proved an attraction. In the late 1960s, Ernie Bach, who ran the gas station and VW repair shop on the Tofino waterfront, started taking groups of visitors on “Sea Lion Cruises.” They left from Tofino in his large cabin cruiser and went to Sea Lion Rocks off Long Beach. “We were appalled at how he blew his horns and disturbed the sea lions,” Carolyn said. These original sea lion tours stopped in 1970. Jim and Carolyn then approached the director of the newly formed Pacific Rim National Park “to describe our vision of an ‘environmentally conscious’ Marine Mammal Interpretive Cruise,” requesting permission to run such tours from the park amphitheatre at the north end of Long Beach. They proposed going directly from there out to Sea Lion Rocks with a park naturalist on board to talk about the wildlife.

Every summer from 1971 to 1976, these cruises ran from Long Beach. “At first we advertised them just as sea lion tours,” Jim Hudnall recalled, “but we soon realized we could always count on seeing grey whales so we began advertising as whale tours—the first in the area.” Jim strung a rope from the beach to an anchored buoy out beyond the surf and pulled his Boston Whaler to and from shore. “People sometimes got wet.” Once he had loaded a maximum of twelve passengers, he would haul the boat out to sea until the water was deep enough to lower and start the engine. A trip to Sea Lion Rocks cost four dollars and took ninety minutes; Jim ran four trips daily in the summer. Carolyn took care of the bookings and publicity, posting cheerful hand-coloured signs around Tofino. As the operation grew, Doug Palfrey and Jim Darling joined the ranks of employees, along with Marta Fiddy, who worked as office manager from a disused home on the beach.

Others soon realized the potential of adventure travel and ecotourism and began offering wildlife and whale-watching trips around Meares Island and to other areas of Clayoquot Sound. Jamie’s Whaling Station began operations in 1982; Shari Bondy started up the first whale-watching business using Zodiacs in 1985; Remote Passages Whale Watching and Sea Kayaking opened in 1986, as did Ospray Fishing Charters. Dorothy Baert of Tofino Sea Kayaking first offered kayaks to rent in 1988. In 1987, Tofino hosted its first annual Whale Festival. From these beginnings, the town’s fame as a centre for whale watching and wilderness adventure grew and spread.

In 1983, sport fisherman Dick Close began building the Weigh West Marine Resort on the Tofino waterfront. One of the first tourism entrepreneurs, Close offered fishing charters, rental boats, and “all in” packages to visitors. “The whole thing kind of evolved over the next decade or so,” Close commented. “First we built some rooms, then added a pub, then more rooms, then a restaurant, then more rooms.”

Some of the adventure tours of Clayoquot Sound began taking visitors to Hot Springs Cove on the Openit Peninsula, about thirty kilometres northwest of Tofino, at the entrance to Sydney Inlet. Al Pineo offered visitors the first day-long return trips to Hot Springs Cove in 1982, aboard his boat Barkley Pacific. He went up “the inside” through the passages and inlets of Clayoquot Sound, returning on “the outside” along the open coast, viewing basking sharks, birds, orcas, and grey whales en route, with a relaxing soak in the hot springs as the highlight of the trip. Long known to the Nuu-chah-nulth as Mok-seh-kla-chuck, meaning “smoking waters,” the hot springs average 50 degrees Celsius. Visitors walk for some twenty minutes along a boardwalk to reach the springs, where geothermal water bubbles out of the ground at 455 litres a minute, cascading down a series of pools and small waterfalls to the open ocean. Most of the early tourists happily joined in the tradition of entering the springs naked. “People who wouldn’t have taken their socks off in public would strip off buck naked there,” Al Pineo remembered.

For years, mariners referred to this location as Refuge Cove, noting the safe anchorage it afforded from the open Pacific Ocean. Local storekeeper Ivan Clarke served as postmaster there from 1936 onward; first known as Sydney Inlet Post Office, the name changed in 1948 to Hot Springs Cove Post Office. The following year the Hydrological Survey of Canada officially changed the community’s name from Refuge Cove to Hot Springs Cove, to distinguish it from Refuge Cove on Redonda Island in Desolation Sound. When the Clarke children, eight of them, needed to go to school, local fishermen helped Ivan build a one-room schoolhouse. This Sydney Inlet School opened in 1946, with thirteen children attending—mostly Clarkes, plus a few of the younger Rae-Arthur children from Boat Basin in Hesquiaht Harbour. The school ran until 1960, with the name officially changed to Hot Springs Cove School in its final year. For many years without a school, in 2008 the Hesquiaht First Nation Place of Learning opened at Hot Springs Cove, a large, beautifully designed building combining community centre and elementary school, overseen by a totem pole donated by Chief Dominic Andrews.

Back in the 1930s, Ivan Clarke began selling fuel as Standard Oil’s agent at Hot Springs Cove, and he established a busy fish-buying station there. For years, he and his family packed, iced, and shipped fish out to Victoria. Art Clarke remembered working there even at the age of eight: “We iced fish all night, as much as 30,000 pounds [13,600 kilograms]. Once we iced 75,000 pounds [34,000 kilograms].” Upward of 200 trollers made Hot Springs Cove their base during the eight-month-long fishing season. When not out in their boats, the fishermen often soaked in the springs, using the hot water to wash their clothes.

Bruce Lucas grew up in Hot Springs village in the 1950s and knew every fish boat in the cove: “Some of the boats I remember were the Coho King, the Boulder Point, Eileen C, Swan, Restless, SS Hesquiaht Flyer, Lenny Boy, Tidewater, Audrey S and of course the mighty Seven Oaks. These boats fished just about all year round, fishing for spring salmon in April and progressing into coho, sockeye and pinks in the summer. During the winter months, these boats would troll and jig for ling cod and other ground fish. Our fishermen did not rely on employment insurance benefits or welfare; they were very hard-working men.”

Hot Springs Cove became home to many Hesquiaht people by the 1950s. It had long been a place they used as a safe refuge and a fishing station, and in 1874 Father Brabant noticed, on his first visit to the cove, that “here quite a number of Hesquiaht Indians were living.” The traditional winter village site of the Hesquiahts, on the outer shore of Hesquiaht Harbour, became less viable as the twentieth century advanced, given the increasing number of motor boats. Although an ideal location for launching dugout canoes, the village could not provide safe moorage. Father Charles Moser’s diary documents many instances of motor launches being damaged at Hesquiaht during storms, and Father Charles mentioned discussions about moving the village site as early as 1915. The move happened slowly—in 1931, when visiting Hot Springs Cove with the hydrological survey, Jack Crosson noted “no buildings of any kind, not even an Indian shack.” But gradually, most Hesquiahts did move away, many to Hot Springs Cove, abandoning the old village. By 1950, when Father Maurus Snyder visited the west coast after many years’ absence, he described Hesquiaht village as “nearly depopulated.” In the late 1950s, Father Fred Miller twice visited Hesquiaht to report on conditions there to his superiors. “Poor old Hesquiaht,” he wrote. “It was a little the worse for wear.” He found houses that had “given in to the inevitable and laid down in the sallal brush.” The once dominant church of St. Antonin stood vacant and unused, silently rotting away, its windows broken, its roof leaking, the buckling floor strewn with mildewed books and vestments. The era of the ambitious mission had ended, and the “great herd of cattle [Father Brabant] started now roams wild through the woods.”

On the night of March 28, 1964, an earthquake near Anchorage, Alaska, measuring 9.2 on the Richter scale, sent a tsunami surging down the west coast. It wiped out the Hesquiaht village at the head of Hot Springs Cove, carrying away sixteen of the eighteen houses. Some of them burst into flames as coal oil lamps upset, igniting the buildings. Luckily everyone survived the experience, save one cat. “It was the second wave that pulled about four or five houses out into the bay,” reported Sue Charleson, who lived through the horror. “They were drifting on top of the water with people inside. A couple of the houses were in flames…In the meanwhile, the fuel lines must have broken at the [Clarke’s] store near the government dock. It was lucky that those burning houses did sink before they reached the spilled fuel.” After the event, most residents left the cove and it was more or less deserted for a few years. During the late 1960s, “Refuge Cove IR 6” became a Hesquiaht Indian Reserve, and eventually Hesquiaht people returned there, re-establishing themselves on this new village site, on higher ground northwest of the original village site.

In 1955, Ivan Clarke donated fourteen hectares of his original 48.5-hectare pre-emption to the provincial government for a park, leading to the creation of Maquinna Marine Provincial Park. Forty years later, in 1995, the Clayoquot Sound Land Use Decision saw the province add an additional 2,665 hectares to the park, incorporating many kilometres of coastline in Clayoquot Sound. The park then encompassed Hesquiaht Peninsula, the coastline around Hesquiat Harbour and down to Hot Springs Cove, the outer coasts of both Flores and Vargas Islands, as well as other sections of coastline. In 1968, Ivan Clarke sold the rest of his land and retired, having lived over thirty years at Hot Springs Cove.

On Meares Island, Christie Indian Residential School at Kakawis closed for good at the end of June 1971, condemned as a fire hazard. During the school’s final two years, at the insistence of the fire inspectors, the dormitories all moved downstairs, with the upper floors used only for recreation and for sewing classes. In the decade before it closed, the school had undergone many changes. The Benedictine sisters withdrew in 1961, handing over to the Immaculate Heart sisters from California. From then on, the school offered full days of classes, rather than only a few hours of instruction. During the 1960s, pupils no longer had to attend daily mass in the chapel, and boys and girls—formerly so strictly segregated—could now socialize, sharing sports activities and holding occasional dances, with rock ’n’ roll music coming from the record player. Volleyball and basketball remained the favourite sports; one team called themselves the “Mush Eaters.” Everyone hated the school’s oatmeal.

Faced with the old school’s closure, the Christie School Board reached a landmark decision. The board, made up largely of First Nations representatives, decided to build a residence for 100 Christie students in Tofino. After much deliberation, they decided that Indigenous students from around Clayoquot Sound, at least those in elementary school, would live in this purpose-built residence and attend an integrated public school in Tofino. School integration had already begun in Tofino, for when the Opitsaht elementary school closed in the mid-1960s, students from Opitsaht entered the public school in Tofino, commuting back and forth to their village. In the latter years of Christie School on Meares Island, only a few students attended from Opitsaht or from Ahousaht; most came from villages farther up the coast—Hot Springs Cove, Hesquiaht, Yuquot, and Kyuquot. Ahousaht students attended the publicly funded elementary school in their own village, the Presbyterian school having closed. Most Ahousaht students attending high school went to residential schools at Alberni, Mission, or Kamloops. Those same residential schools also absorbed the high school students who had attended the old Christie School on Meares Island; the move into Tofino to attend school did not include high school students.

The plan to bring all the Christie School elementary students into Tofino led to the federal government agreeing to fund construction of a large new school in Tofino as well as a residence for the Indigenous students, at the location now known as Tin Wis on MacKenzie Beach. By September 1971 the residence had been completed, and 100 students moved to their new accommodation. Administered by the same staff who had worked at Christie School, most of whom lived on site, this new residence provided recreational facilities and far more space. “Each boarder will have his own room,” declared the Colonist, “a far cry from Christie School’s crowded dormitories.” The new Wickaninnish School in Tofino would not be ready for another year, so during the 1971–72 school year, Tofino students from Grades 5 to 7 took a bus to the “New Christie” residence, as it became known, and attended class with students from the former Christie School there. Children in Grades 1 to 4 living at the New Christie residence bused into Tofino each day to attend classes at Tofino Elementary School. After that initial year, no classes took place at New Christie; students there all travelled by bus to the Wickaninnish School in Tofino. Following the closure of New Christie residence in 1984, the building became offices for the Tla-o-qui-aht administration, then a guest house, before being incorporated into the Tla-o-qui-aht-owned Best Western Tin Wis Resort.

The eleven-room Wickaninnish School opened in Tofino with grand ceremony in April 1972, declared “the most modern [school] in BC” by the Tofino-Ucluelet Press of April 20, 1972. Participants at the opening included Len Marchand, then the only Indigenous member of Parliament; Donald Brothers, minister of Education; and well-known aboriginal writer George Clutesi. “Mr Clutesi declared,” according to the local newspaper, “that today’s Chief Wickaninnish, George Frank of Opitsat, gave his most cherished possession, his name, to the new school.” Alma (Arnet) Sloman, “the oldest graduate of Tofino’s original one-room school,” also took part in the ceremony, unveiling a commemorative plaque.

Across the water from the ever-busier Tofino scene, the old hotel at Clayoquot on Stubbs Island soldiered on. After Betty Farmer sold the place in 1964, mining developer Andy Robertson of R&P Metals took it on, hiring caretakers who managed the property for him for a number of years. Robertson did not live there but came and went, pursuing various mining interests in the area. In 1964 he also purchased a half interest in Tofino’s Maquinna Hotel, in partnership with one of the original owners, Dennis Singleton. Robertson anticipated lively comings and goings of mining men and their families in his two hotels if his mining interests flourished. In the end, this failed to happen, yet the hotel at Clayoquot carried on, serving dinners and drinks and attracting visitors to stay at the eight-room hotel. Under the management of Paul and Freda Brown, the place became well known for its excellent food, and the island still welcomed locals for memorable get-togethers. In a reminiscence written for The Sound, Frank Harper described the Clayoquot Day festivities in 1974, with over a thousand people on the island, featuring baseball, mass drumming, picnics and barbecues, boats going in all directions, the bay alive with activity. He wrote of the eccentric chef at Clayoquot: “a genius cook and intellectual from Belgium named Yves who wore bright-striped robes and yellow wooden shoes and smoked a pipe and cursed you if you put salt or pepper on the food he’d prepared.”

In 1977, Lucas Stiefvater purchased Stubbs Island, essentially working in partnership with Andy Robertson, who held a mortgage on $450,000 of the $500,000 sale price. Stiefvater ran the hotel and restaurant at Clayoquot, acting as chef, boat operator, and gardener. During his time there, the old store still stood, teetering on the edge of ruin on the eroding beach, its floor and roof slowly collapsing, used mostly as a storage shed. Stiefvater and his staff recognized the historic value of Walter Dawley’s boxes of dusty old papers, which had lain around for decades, first in the old store, then in the hotel. They contacted the provincial archives in Victoria, an initiative that led to the archives acquiring the papers. Dawley’s incoming correspondence of more than thirty years now fills 8.3 metres of shelf space, a treasure trove of historical information about the coast.

In 1978, rooms at the Clayoquot Hotel, meals included, cost forty dollars per day, and dinner commanded a set price of fifteen dollars, including transport to and from the island, according to a Vancouver Sun article of June 23, 1978. “The ancient beer parlour is long gone,” lamented the writer, not mentioning that the liquor licence for the entire establishment had quietly lapsed years earlier. No one dreamed of asking awkward questions when the hotel restaurant continued serving alcohol.

By 1980, ownership of the island had become highly convoluted, and would remain so for the next decade. Stiefvater and Robertson attempted to sell the place to Frank Neufeld, who brought a complex and dubious property scheme into play. Sun and Sea Development set out to attract shareholders who invested believing they would receive a small plot of land on the island and a time share in the hotel.

Publicity for Sun and Sea Development announced that the Clayoquot Hotel and restaurant would close following the summer of 1980, and from then on the island would “accommodate less than 120 individual owners with their own private island retreat,” sharing a central park, the lodge, and the dock. Neufeld advertised plots of land for sale at $15,000 each, with $3,000 down, selling the lots from a hand-drawn map never officially registered as a subdivision with the Alberni–Clayoquot Regional District. The planning department at the regional district first heard of this scheme in the advertisements and repeatedly refused to sanction such a subdivision. Nonetheless, many people stubbornly believed the subdivision would eventually obtain planning permission, and over 100 people invested in the scheme. All lost their money. A Vancouver Sun article of June 23, 1984, headlined “Investor dreams sour in $1 million loss,” described how “a fantasy island…turned into a million dollar financial nightmare,” following a BC Supreme Court decision stating that the would-be investors had no claim on the island. Any agreement they had signed proved non-binding, being conditional on the approval of the regional district. In a personal memoir, former Clayoquot Hotel manager Al Pineo wrote, “I find it hard to believe how many people bought a piece of Stubbs Island with nothing to show for their investment but a hand crafted map with a lot number on it that was never going to result in actual ownership.”

In 1982, with the property development scheme going nowhere fast, Al and Dorothy Pineo took over as caretakers and managers on the island, and they set out to revive the hotel and restaurant. Determined to bring new energy to the place, and realizing that accommodation was increasingly difficult to find in Tofino, they announced that the eight-room hotel was once again ready for guests. They offered to cater banquets and special events, and before long the old place had come back to life. “I think people were dying to have Clayoquot back,” Al Pineo explained. During their three years on the island, the hotel ran at capacity during the season, and the forty-seat restaurant booked solid with two sittings each night, customers reserving tables up to two weeks in advance

In 1985, the Pineos left. Following foreclosure, the island changed hands and local businesswoman Olivia Mae took it over. Under the business name Boardwalk Developments Ltd., Mae approached the regional district about selling lots on Stubbs Island based on Walter Dawley’s early subdivisions. She and her partner, Annaliese Larsen, prepared publicity information, offering ten beach lots for sale and stating in their publicity that “arrangements are in place to pipe water from nearby Tofino.” Tofino council knew nothing of this and “strongly recommended” that Olivia Mae stop these advertisements, according to an article entitled “Fingers Rapped,” in the Westerly News of January 23, 1985. Sporadic marketing efforts continued while local rumours whirled about further development schemes, including time shares, a golf course, foreign investment, and another subdivision. The Westerly News of February 26, 1986, reported a major expansion planned for Clayoquot Lodge to transform it into “a world-class destination,” but the owners “won’t yet make public their plans for the resort,” other than saying trips to the island would be available for afternoon tea. As time passed, the island welcomed fewer and fewer visitors, the hotel and restaurant closed, and locals looked on, nonplussed. By the end of the decade, the old hotel had suffered a fire, and the house where Ruth and Bill White had lived in the 1940s burned to the ground in 1985. Busy, bustling Clayoquot, once the major hub of all commercial activity in Clayoquot Sound, ceased to exist.

In 1990, Susan Bloom bought the island, once again in foreclosure, and all talk of development and subdivision ceased. Determined to tidy up what remained there, to restore the gardens, and to preserve the island and its forest intact for future generations, Susan Bloom brought in dedicated caretakers who worked tirelessly with local contractors to dismantle the old, crumbling buildings, rid the place of disused machines and debris, and rebuild the dock. With great care and hard work, the gardens gradually expanded and found new life, and extensive boardwalk trails on the island were constructed. The renaissance at Clayoquot did not include a hotel or restaurant; those days have ended, and the island is now a nature reserve. Until the outbreak of Covid 19 in 2020, the tradition continued of welcoming people at Clayoquot for the May 24th long weekend, with the gardens open to visitors.

From 2007, the forest on the island, covering some 75 percent of its area, became protected by a conservation covenant, registered through The Land Conservancy of British Columbia. In 2016, Susan Bloom donated the majority of the land on Stubbs Island to the Nature Conservancy of Canada, ensuring it will be protected and cared for in perpetuity.

Farther offshore, Wickaninnish Island has remained even less affected by all the recent change in the area. Difficult to access and with no safe moorage, the island fell into private hands before World War I, when Walter Dawley pre-empted and later purchased the entire island. It has never been subdivided, remaining intact as one large parcel of land as it passed through the hands of several owners over the years. No one logged it or built any substantial structures there, and in the early 1970s the island again came up for sale. Vicky Husband and Suzanne Hare, two former beach dwellers from Schooner Cove, reached an agreement to purchase it, with a view to maintaining the island as a place where a small group of like-minded people could create a co-operative land use and living agreement. Under the terms of a rezoned “land use contract,” the island was designated for “co-operative seasonal development under strict environmental controls.” Several leaders in the environmental movement became involved: Greenpeace pioneer Lyle Thurston, early Greenpeace supporters Myron Macdonald and David Gibbons, and Vicky Husband, who became conservation chair of BC’s Sierra Club. Now some sixteen people share ownership of the island; most come and go seasonally.

Through the 1980s and ’90s, the Tofino community became increasingly polarized around environmental and land use issues; years of strife and division ensued, leading to intensely bitter local disputes and enmities. Yet at the same time a keen entrepreneurial spirit kicked in locally, and irrespective of the socio-political divides, people of all stripes sensed they could profit from the growing tourist trade, realizing it had come to stay. The early ecotourism enterprises involved everyone from former hippies to developers, as did the service industries in town, and everyone catering to tourists knew that visitors did not want to see clear-cuts. Around Ucluelet, and in many other locations on the coast, vast areas had been laid waste by clear-cutting, mudslides, and slash-burning; such landscapes silenced and appalled visitors. No one in Tofino with a finger in the pie of the growing tourist trade wanted to see that in their own backyard.

A group of the new entrepreneurs in town seized the chance to make their voices heard early in 1987. Maureen Fraser of the Common Loaf bakery; Joan Dublanko, who opened the first bed and breakfast in Tofino at Chesterman Beach in 1986, and who also ran the Three Crabs Deli along with Cristina Delano-Stephens; Al and Dorothy Pineo, who in 1986 took over management of the Loft Restaurant; Shari Bondy, who ran whale-watching tours; and Dorothy Baert, about to open her kayak rental business, decided to attend a Chamber of Commerce meeting. None were members, but they joined then and there as local businesspeople. They outnumbered the old guard and basically took over the local branch, voting each other in as officers, passing all their own resolutions, and starting to actively promote Tofino as a tourist destination, putting forward the idea that clear-cut logging must stop if the town wanted tourists. In the late 1980s, the Tofino Chamber of Commerce sent a telegram to the provincial government asking for a halt to logging in Clayoquot Sound—an unprecedented action for a Chamber of Commerce.

Wholesale promotion of tourism troubled some long-time residents. “At first people resented the tourists as an infringement on their privacy,” Mayor Penny Barr admitted to the Seattle Times in July 1983. “But we’re right next door to a national park that has about half a million visitors a year. So we don’t have a choice of having tourists or not…More visitors are coming every year—people always want to see the end of the road.” She stressed the need for good long-term planning, acknowledged the growing pressure for development, and concluded, “We have to get our act together.” These concerns would prove very real for Tofino, for the visitors just kept coming. An article in the Victoria Times Colonist dated May 12, 1985, estimated the town’s population at 350 in the winter and over 3,000 in the summer.

A perfect storm of events led to the introduction of aquaculture in Clayoquot Sound in the mid-1980s. With both the herring and salmon fisheries in decline, with opposition to logging growing, with BC suffering through a recession, and with the Social Credit government looking to stimulate foreign investment in the province’s resource industries, the government opted to allow fish farms on the west coast. This occurred just as Brian Mulroney’s federal government passed a bill rescinding the requirement that Canadians hold majority ownership in Canadian-registered companies. At the same time, Norwegian fish farm companies were looking to move to Canada and other countries because the Norwegian government had placed limits on the size of fish farms there. Fish farming promised to provide jobs, to help feed the world, and to reduce pressure on salmon stock; it seemed, on the face of it, a perfect solution to several problems.

In 1985, Ian Bruce, a fisheries biologist, became a partner in the first fish farm in Clayoquot Sound, Sea 1 Aquafarms Ltd., located in Irving Cove in Tofino Inlet, where its nets hung below floating cedar logs. Other farms opened shortly after at Mussel Rock and Saranac Island, both northwest of Meares Island. These early farms began by raising native chinook and coho salmon, but by 1993 most salmon farms were producing Atlantic salmon because of their faster growth rate. As more and more fish farms began raising Atlantic salmon at various locations on the BC coast, environmentalists began voicing their concerns about these alien fish escaping and breeding with wild Pacific salmon. In April 1995, in response to these concerns, and also because of a decline in wild fish stocks and the death of 100,000 fish at a farm on the Sunshine Coast, the provincial NDP government placed a moratorium on new fish farms. In 2002, the newly elected Liberal government of Gordon Campbell lifted that ban.

In 2000, when salmon prices fell drastically, the aquaculture industry underwent consolidation. With the lifting of the seven-year moratorium, a few multinational corporations secured even more control of fish farming in BC. They built new, larger, more automated fish farms in order to cut costs, at the expense of small, family-owned operations. By 2007, Norwegian-based corporations controlled 89 percent of all fish farming in British Columbia—Marine Harvest had 56 percent, Cermaq (Mainstream Canada) 23 percent, and Greig 9 percent.

When fish farming arrived in the Sound in 1985 it created much-needed local employment. As wild salmon runs declined, the Tofino Fish Plant, owned by B.C. Packers since 1980, began to founder. It closed in 1982, throwing people out of work. The Meares Island logging standoff in 1984 (described in Chapter 21) also caused Tofino to suffer economically. “Thankfully the fish farming industry began and that kept the town going,” said former mayor Whitey Bernard. Yet over time, opposition to fish farms increased steadily as environmental groups highlighted a growing litany of problems related to the industry. These included an increase in sea lice in the ideal incubation conditions provided by net pens; escaped Atlantic salmon infiltrating wild Pacific salmon stocks and habitat; the use of antibiotics, pesticides, and steroids to control disease in caged salmon stocks; and the further decline in wild salmon stocks since fish farming began. Farming fish is inefficient; as Peter Robson noted in his book Salmon Farming: The Whole Story, 2.45 kilograms of oil and fish meal from herring, mackerel, anchovies and sardines are required to produce one kilogram of farmed salmon. Opponents of fish farming also point out that the feces, the uneaten food, the pesticides, and the colouring agents (to make the flesh pink) end up deposited in the bays and inlets below the fish pens, smothering the seabed and depriving shellfish and other bottom-dwelling sea creatures of oxygen. “They’re like floating pig farms,” said Daniel Pauly, professor of fisheries at the University of British Columbia in an interview with the Los Angeles Times. “They consume a tremendous amount of highly concentrated protein pellets and they make a terrific mess.” Jeff Mikus, a commercial prawn and shrimp fisherman from Tofino, reported to the BC Aquaculture Review in 2005–6: “As time has gone on (about the last five years) we started catching fewer prawns, shrimp and other sea life in our traps around fish farms…Sea lice are a huge problem in fish farms. They use a chemical called Slice to kill sea lice infestations in the net pens…[it] kills crustaceans, like sea lice, but it also kills prawns, shrimp and crabs…The problem here is that there are so many farms in such a high density in such a small area that there are very few places to go to get away from them.”

In 2002, 200 tonnes, or 80,000 fish, died at Cermaq’s Bedwell Sound farm from a suspected outbreak of infectious hematopoietic necrosis (IHN); in 2003 another spate of IHN hit five of Cermaq’s farms, forcing them to cull their stocks and to close for a year. Nine years later Cermaq had to destroy another 570,000 fish at its Dixon Island fish farm, and when the IHN virus hit Mainstream’s farm at Millar Channel, the firm lost an estimated $10 million when it was forced to cull all of its stock and disinfect the site.

When Cermaq gained approval to build a new fifty-five-hectare fish farm in Clayoquot Sound in 2012, a dispute erupted between the Tla-o-qui-aht and the Ahousaht. The farm would be located at Plover Point on Meares Island, an area traditionally shared by the Ahousaht and Tla-o-qui-aht First Nations. Sixty Ahousahts worked with Cermaq, and the Ahousaht First Nation favoured the fish farm being located at Plover Point. The Tla-o-qui-aht opposed the farm and threatened a lawsuit to prevent its establishment. In the end, despite much opposition, the project went ahead.

Despite unyielding opposition from environmentalists, and despite the removal of fish farms from other areas of the west coast, most notably the Broughton Archipelago, fish farming in Clayoquot Sound appears to be here to stay. In the face of federal government declarations about phasing out open-net pen salmon farms in BC waters by 2025, twenty such farms were operating in the Sound in April 2023, the highest concentration anywhere on the west coast of British Columbia. By contrast, such salmon farms are banned in the coastal waters of Alaska, Oregon, California and Washington state.

Progress is slowly being made to rectify some of the problems associated with fish farms, including investment in closed-containment, land-based fish farms. In 2013 the ‘Namgis First Nation established BC’s first such plant near Port McNeill. However, until closed containment becomes more widespread, opponents of fish farms are calling for the industry to regularly leave existing farms fallow to allow the bays and inlets where they are located to recover. Also, in order to reduce the risk of disease, they recommend having 20 to 30 percent fewer fish in each pen. Some opponents want to rid the British Columbia coast entirely of all fish farms, proposing that BC live up to its “Super Natural” slogan and create a niche market for fresh wild salmon as a superior product fetching higher prices from those willing to pay more for good natural food. British Columbia is hard pressed to compete in the farmed fish market with nations like Norway and Chile; because of their economies of scale, those nations produce farmed salmon far less expensively. Meanwhile, with many locals employed by the fish farms in Clayoquot Sound, restaurants in Tofino offer nothing but wild salmon on their menus. Farmed salmon is not served locally.

Environmentalists and marine scientists generally endorse the farming of oysters, clams, and mussels, as these bivalves filter and clean the water they live in. With this in mind, Roly Arnet retired from both school teaching and salmon fishing in the 1980s. The grandson of Jacob Arnet, who held Tofino’s first salmon fishing licence in 1898, saw the writing on the wall: “I could see that the salmon industry was declining. It was being over-exploited and there was no commitment by the government to protect salmon habitat.” In 1985, Roly borrowed $50,000 from Ecotrust and established an oyster lease on the west side of Lemmens Inlet. After a run of successful harvests, he increased the size of his lease to ten hectares in 2000 and involved his nephew Derek in the project. A fourth-generation Arnet now operates this eco-friendly commercial enterprise in Clayoquot Sound. “It’s one of our goals to create a quality brand locally and internationally.” About 3.2 million oysters a year are currently harvested in Clayoquot Sound; Lemmens Inlet supports most of the commercial oyster farms, with some half-dozen leases there. Since 1997, Tofino has hosted a two-day Oyster Festival in November, with eager participants downing over 10,000 oysters.

Just as new local enterprises came on stream during the 1980s, the forestry industry faced its west coast Waterloo. A logging blockade on Meares Island in 1984 saw the opening salvo fired in a gradually mounting storm of protest, confrontation, and publicity, pitting logging interests against environmental activists and aboriginal leaders in Clayoquot Sound. A titanic confrontation lay ahead, one that would eventually attract worldwide notice. International attention had last focused on the west coast of Vancouver Island almost two centuries earlier in 1790, when the Nootka crisis nearly led to a war between Great Britain and Spain. This time the “war” would be confined to Clayoquot Sound, but news of the battle would, once again, reverberate around the world.