Chapter 9: “Alive with Fish”

When the first Europeans arrived on Vancouver Island’s west coast, the sheer wealth and variety of marine resources amazed them. “The Coast is alive with fish,” coastal trader Hugh McKay told the British Colonist in June 1859. “Herrings, large and fat, can be taken in shiploads, and so can salmon and dogfish. Along Clayoquot Sound, codfish can be taken in large quantities.” Yet despite the evident potential, several decades passed before any serious attempts at commercial fishing began in Clayoquot Sound. This changed when Thomas Earle came on the scene in the spring of 1893. Within a short time of his arrival, Earle determined to open a salmon cannery in the Sound. He knew the business well, for in 1888 he had become a partner in the Alert Bay Canning Company on Vancouver Island’s east coast.

Initially, Earle seized the opportunity to exploit the annual salmon runs by opening a saltery at Clayoquot, salting down fish in barrels. On September 25, 1892, the Colonist reported: “Steamer Mystery, Captain Brown, returned to Victoria last evening from a long and wearisome trip down the West Coast, she brought back as passengers a number of salmon fishermen who early in the season had been supplied with a large number of empty barrels along with several tons of salt to go down to Clayoquot Sound and there catch and pack salmon.” Mystery returned to Clayoquot in early December 1892 “with four Norwegian fishermen, a quantity of lumber and a large amount of supplies, for the fishing station located there. The Norwegians are men who came out from their native country about 7 weeks ago with the object of leaving on their present expedition. In their own land these men were regarded as experts at their business.” Several months later, Mystery again delivered salt to the station, and in May 1893 she headed to Stubbs Island with Thomas Earle and Alfred Magnesen on board. Even after Earle opened his cannery at Kennfalls in 1895, the saltery at Clayoquot continued packing fish in barrels for years to come. The Colonist reported six years later, on October 1, 1901, that “Talbot and Jacobsen of Clayoquot, and Feker of Kyuquot, have put up from 80 to 100 barrels of salted salmon.” A barrel usually held ninety kilograms of salmon.

By 1893, Earle had entered a partnership with Magnesen, his bookkeeper and accountant. Magnesen had arrived in Victoria six years earlier from Stavanger, Norway, and he had strong connections within the Norwegian immigrant community in British Columbia. Following two seasons of salting salmon in barrels, on December 22, 1893, Earle and Magnesen formed the Clayoquot Fishing and Trading Company. The Colonist announced: “The Clayoquot Fishing & Trading Co Ltd liability, publish their memorandum of association, Alfred Magnesen, Cecil Fletcher and Robert A Cunningham, all of Victoria, as the trustees. The settled object is to engage in the business of fishing, sealing and trading generally, the capital stock to be $15,000, in 100 shares.” Typically, Earle’s name does not appear at the forefront of the new company. Because of his involvement in so many business ventures, he generally stayed in the background, allowing his managers to assume control of the day-to-day affairs. He also may have been trying to avoid any perception of a conflict of interest associated with his position as a Member of Parliament.

By the summer of 1895, Earle and Magnesen had employed a number of settlers to help build a one-line cannery some twenty kilometres east of Clayoquot, at the mouth of the Kennedy River, where the fish congregated before swimming up to their spawning grounds in Kennedy Lake. By August, according to the Colonist, “The cannery at Clayoquot, established somewhat as an experiment, has already 3,000 cases of salmon ready for the market with another 1,000 to follow this week. The supply of fish greatly exceeds the capacity of the cannery.” At that time, the industry standard for a case of salmon consisted of forty-eight one-pound cans, most exported to Britain, where it was not uncommon for a working man to eat a can of salmon, at half the cost of beef, for lunch. By 1897, British Columbia canneries shipped $3 million worth of salmon to Britain.

The establishment at Kennfalls, typical of canneries at that time, came to resemble a small village. The main cannery building sat on pilings surrounded by a series of docks, and within stood rows of washing and cutting tables where Chinese workers cleaned, washed, and cut the fish into pieces. Indigenous women packed the pieces into the cans. The Chinese soldered lids onto the tops, leaving a small vent hole, and the cans went into the steam retort for cooking. Afterward, with the vent holes soldered shut, workers lacquered the cans to prevent rust, tested them, labelled them, and packed them into cases for shipment. The cannery boiler needed a mountain of firewood to keep it running during the canning season. Accumulating that firewood gave many Clayoquot Sound settlers paid work during the winter.

Right beside the main cannery stood the can loft and tin shop, which opened for business well before the fishing began, with workers preparing cans for the season. A cavernous net loft stood in another separate building. Here seine nets, made of linen and cotton, hung to dry or to be repaired. The floor of these lofts had to be very smooth so as not to snag the nets, and it served a double purpose as a perfect dance floor on occasion. “The old cotton nets tore easily and needed a great deal of skill to repair them,” recalled Ian MacLeod, who used these nets fishing out of Tofino as a young man.

Although considered small by industry standards, the Clayoquot cannery still needed a substantial and steady supply of fish during the season. Alfred Magnesen sought out Norwegians already fishing for Fraser River canneries, enticing them to come to Clayoquot Sound with their small sailing vessels to catch salmon for the cannery. He also employed Indigenous fishermen, who fished from their canoes, often using their wives for additional paddle power. None of the fishermen had to go far afield, for the salmon schooled around the mouth of the Kennedy River, right in front of the cannery.

Sid Elkington, who worked at Kennfalls from 1923 until 1929, described in his unpublished memoirs how the fishery worked: “The sockeye fishing was concentrated at the head of Tofino Inlet near the mouth of the river, close to the cannery. When the later runs of salmon, Chum Cohoe—with scattered Pinks and Spring, entered the Sound, they scattered to various streams in various inlets to spawn, so fall fishing was carried out over a wide area, and additional boats, owned and crewed by Indians from Opitsat and Ahousat reservations joined in the fishing. The total salmon runs of Clayoquot Sound were just sufficient to amply supply a small cannery such as Kennfalls, all taken by purse seines in inside waters.” In the early years, fishermen pulled their purse seine nets aboard by hand—power-driven rollers and winches, invented in the 1920s, eventually relieved them of this back-breaking task. Sometimes, to avoid hand-hauling the net, fishermen towed the net to shore and there dispatched the fish into skiffs.

From the skiffs, the catch went into a nine-metre-long scow and then was towed to the cannery. Fishermen worked from dawn till dusk in their open boats, their pay based on the numbers of fish caught, ranging from a few cents to ten cents a fish, depending on demand. Sometimes the catches proved so large the cannery could not keep pace; with no refrigeration, the company had to impose fishing closures, never popular with the fishermen. The Colonist described one such closure on August 16, 1895, in the first season of operation: “For a week or more the operations at the Clayoquot Sound cannery had been all but at a standstill, though a 2nd run of salmon started the rush again. There was trouble with the fishermen, too, for a few days the men wanted pay for their idle as well as busy spells, and refused to work until their demands were accorded to. An amicable settlement was arrived at with the canners, however, and the trouble terminated suddenly.” As time passed, gasoline engines, reliable “one-lungers” built by Easthope Brothers in Vancouver, made fishing easier, although the motorized boats increased the catch, forcing yet more closures.

Hired as storekeeper and bookkeeper, Sid Elkington also tallied the number of fish, kept an eye on temperature and pressure in the steam retorts, ran supply vessels up and down the inlet to Clayoquot, and even stoked the boiler when the engineer had a break. He also would tow the “gut scow” full of fish offal out into the inlet, and one of the Chinese workers would shovel all the fish waste directly into the water.

Although the cannery offered a variety of accommodations, the Indigenous workers mostly lived in their nearby summer village, Okeamin, at the mouth of the Kennedy River. In the 1920s, some six or eight families from Opitsaht would live there and work at the cannery, arriving every spring to prepare the nets, and staying on to work the season. Other workers stayed in separate, segregated quarters. The Chinese had their “China House,” where they slept, cooked, played mah-jong and fan-tan, and sometimes smoked opium, legal in Canada until 1908. They also grew large vegetable gardens, took care of their chickens, and tended the pigs they brought in to fatten up and eat. As a young boy, Bob Wingen was intrigued by those pigs; he had never seen a pig before. In the early years of the cannery, the Chinese also did some prospecting, sluicing for gold in their spare time. According to the Colonist in 1897: “The Chinamen employed about the cannery devote their evenings and early mornings to the search for the hidden wealth, and although reporting no very important discoveries they are quite as enthusiastic as the rest and can produce at any call quite as many specimens.” The cannery manager lived in a grand house, well distanced from the noise and smell of the workplace. “At our cottage near the cannery there was a big wrap-a-round porch, and sleeping space for fourteen,” recalled Nan Beere. The youngest daughter of Harlan Brewster, who eventually managed and owned the Kennfalls operation, Nan spent her childhood summers at the manager’s house after the turn of the century. “There was a marvelous beach at Kennfalls and I swam there often.” She clearly remembered the dignified presence of Tla-o-qui-aht Chief Joseph, who cut firewood for the Brewsters, and his wife, Queen Mary, who did their laundry.

Alfred Magnesen added another ship to Earle’s fleet in 1896 when he commissioned the Clayoquot to be built, an 24.5-metre coal-fired steamer capable of carrying large freight loads. The Clayoquot set off down Tofino Inlet to Clayoquot every ten days or so to meet coastal steamers—initially the Maude and Willapa; later the Queen City, Tees, and Princess Maquinna—when they made their regular stops there. The Clayoquot loaded up all the food and supplies for the cannery and often took cases of salmon to Clayoquot for shipment to Victoria. The vessel even made occasional trips to the capital city to deliver cases of salmon and to pick up supplies. In 1903 she was replaced by the Edna Grace, which was in turn replaced in 1912 by the gasoline-powered Isku as the cannery’s tender.

Encouraged by the success of the Clayoquot cannery, other fish-processing enterprises began to appear along the west coast. In 1896, Thomas Hooper, the architect from Victoria who designed Thomas Earle’s warehouse and office building, opened a cannery at Nootka. The first season proved a bust for this new facility; few salmon showed up, and it packed only fifty cases. Although it shut down after operating for only two years, another cannery opened at Nootka in 1917 and ran successfully for three decades. In 1897, Messrs. Hackett and McDougall began a small smoked-cod operation at Ahousaht, helping to diversify the area’s fishing industry and providing work for local fishermen ahead of the summer salmon runs. That year they shipped forty to fifty barrels in a two-week period. In 1903 the Alberni Packing Company opened the Uchucklesit cannery on the Alberni Canal, a very successful venture that sold out in 1906 to Wallace Bros. Packing and became the Kildonan cannery. In 1911 another cannery opened farther up the coast at Quatsino.

Ambitious fish-processing schemes have surfaced from time to time in Clayoquot Sound. In 1918, George Brown, principal shareholder in the Union Fish and Cold Storage Company based in Vancouver, proposed building a cold storage plant at Clayoquot on Stubbs Island. The Canadian Pacific Railway’s Mr. H. Brodie, on an inspection trip along the coastal steamer route, reported the plant would have the capacity to “handle as many as a million salmon.” Company documents in the British Columbia archives reveal that Union Fish and Cold Storage bought an 18.5-square-metre parcel of land from Clarence Dawley for $8,000 on March 16, 1918. This small slice of land stood adjacent to the dock at Clayoquot. Construction began on a cold storage plant in 1918, but the following year the Union Fish and Cold Storage Company ceased to exist, leaving at Clayoquot a large and distinctive red building with vents on the roof. Three years later, on November 18, 1922, the Daily Colonist reported that Harry West, a resident of Clayoquot, in partnership with Walter and Clarence Dawley, had applied for a foreshore lease alongside the dock on Stubbs Island, including a building described as “Fish House.” The West Mildcure Salmon Company variously operated a cold storage, smoke house, saltery, and mild cure fish plant in that building in the 1920s, and in later years the building continued to be used as a saltery. In the 1940s, it briefly housed a small crab cannery.

In November 1898, New Brunswick-born Harlan Brewster began working as a purser on the coastal steamer Willapa. Earlier in the decade Brewster had worked with his brother at the Carlisle cannery on the Skeena River, and he had developed an interest in the cannery business. Thomas Earle met Brewster on one of his many trips up the coast and quickly recognized his talents; in August 1899, Brewster became the new manager of the Clayoquot cannery. Like Earle, Brewster took a lively interest in politics; in 1907 he became a member of the provincial legislature for Alberni and the West Coast, and in 1916 became premier of British Columbia.

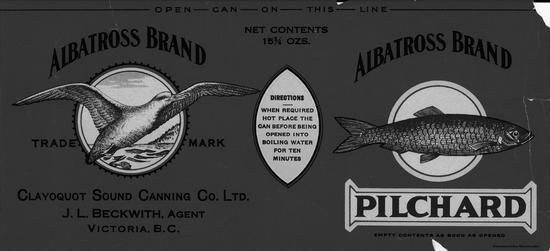

The Clayoquot cannery averaged 4,000 cases per season until 1900, when it produced 7,500 cases. In 1901 it put up 7,000 cases and added Japan to its markets. Yet despite the positive outlook for his cannery, Thomas Earle’s fortunes dramatically collapsed. Forced into bankruptcy in December 1901, two months later he sold the Clayoquot store to Walter Dawley and Thomas Stockham, with Harlan Brewster purchasing the cannery in partnership with J.L. Beckwith and A.G. McGregor. They renamed it the Clayoquot Sound Canning Company, and Brewster continued in charge until his death in 1918. Over the years he made a number of changes in the cannery’s operation, including installing the first commercial fish trap on the west coast in 1906 at Ginnard Point on Meares Island. A heavy tide washed it away that winter, but another, built farther up the inlet, worked more successfully. His most notable contribution to the canning industry remains his introduction of an enhanced sanitary canning system, which saw cans crimped shut and soldered entirely by machinery.

In 1910 the Department of Fisheries built a sockeye salmon hatchery at what became known as Hatchery Beach, on Clayoquot Arm of Kennedy Lake. To construct and to supply the hatchery, all materials and stores had to travel along Tofino Inlet to the Kennedy River rapids, up a trail alongside the rapids, then some twenty kilometres by launch to the hatchery site. This hatchery operated from 1910 until 1935, providing a number of jobs and increasing traffic up and down Tofino Inlet and past the cannery.

Local residents enjoyed occasional visits to the hatchery, where the manager warmly welcomed them. Mike Hamilton, who lived in the area from 1914 to the mid-1920s, first working on the telegraph line and later as a machine shop operator in Tofino, chose to spend his honeymoon at the hatchery, staying in the manager’s house. Mike assured his dubious fiancée that it was “a wonderful place, where there have been several honeymoons already.” Another well-known local couple, Ted and Dorothy Abraham, spent two weeks there in the mid-1920s, enjoying the scenery and the excellent cooking at the manager’s home. The energetic Dorothy investigated the hatchery thoroughly, and asked the manager, William Forsythe, to describe the most exciting event during his time there. His reply came swiftly: “When it rained 11.2 inches [28.5 centimetres] in twenty-four hours!” The overall success of the rain-drenched hatchery remains questionable. Lifelong Tofino resident Ken Gibson said, “It produced a lot of fish but when they put the fingerlings into Kennedy Lake the cutthroat trout ate most of them.”

When the telegraph line arrived at Clayoquot in 1902, the cannery patched into it on a branch line. From the cannery, sixteen kilometres of line extended along the shoreline of the inlet, reaching across to Long Beach, where it hooked into the main west coast line. Maintaining the fragile telegraph line and its various branches provided regular employment over many years to different linemen along the coast, each one responsible for a lengthy stretch. They were often obliged to walk the line in terrible weather in search of breaks, which occurred all too frequently due to storms and fallen trees. After 1914, the line extended beyond Clayoquot all the way to Nootka, looping crazily from tree to tree and over bays and inlets along many shorelines, connecting remote homesteads and enterprises and the ever-increasing number of mining camps.

By the 1920s, pilchards began appearing on the west coast for the first time in living memory. Edgar Arnet first noticed them in Tofino Inlet in 1917; after talking to Indigenous people he learned that these fish had long been used for cooking, heating, and lamp fuel during the intermittent periods when they showed up on the coast. No one quite knew where they came from, or why, but these extremely oily fish, about the size of a sardine, began turning up in such staggering numbers that the shoals extended for kilometres. “There were literally millions of tons of them,” recalled Mike Hamilton. “The Sound teemed with them. They made a sight to be remembered when after dark one could stand in the bow of a power boat and watch the phosphorescent millions hastening out of the way.” Eleanor Hancock, in Salt Chuck Stories from Vancouver Island’s West Coast, described them as “bubbling silvery carpets in the inlets.” Their arrival in such numbers ushered in a period of intense commercial activity on the coast. Some canneries, including the Clayoquot cannery, attempted to can pilchards. In 1917, Nootka Cannery put up 10,000 cans of herring and pilchards, along with 45,000 cans of salmon. Mr. H. Brodie of the CPR, who visited Nootka Cannery in 1918, reported that during the one night he stayed there, twenty-five tons of pilchards came in, at least some of which would be canned. “When cooked at a pressure of fifteen pounds for eighty minutes,” wrote Mike Hamilton, “this reduced the many bones they possessed out of existence and made them very pleasant eating.” Not everyone agreed, and canning pilchards proved unprofitable.

The real value of the pilchards lay in reducing the fish for oil, then drying the remains for fish meal. By the mid-1920s, no fewer than twenty-six pilchard reduction plants had sprung up on the coast, scattered along the inlets between Barkley Sound and Quatsino Sound. Through the 1920s, while the pilchards remained abundant, these plants thrived, many becoming regular stops along the coastal steamer route up the west coast. The Clayoquot Sound Canning Company opened a reduction plant at Shelter Inlet, one of six such plants within the Sound. The Gibson brothers, based at Ahousaht, used their piledrivers to set the foundations of many of these plants, and in 1926 they built their own reduction plant at Matilda Creek near Ahousaht. In the 1928 season, fishermen harvested 80,000 tons of the little fish, sometimes hauling in 200 to 300 tons of them in a single set. Yet even during the boom years the pilchard runs could be unpredictable, and the reduction plants opened and closed accordingly. In his diary, Father Charles Moser, then the Roman Catholic missionary at Opitsaht, noted a temporary shutdown in September 1926, when all the reduction plants on the coast closed because the pilchards had stopped running. Even so, no one dreamed that the pilchards would stop completely. They did. Just as mysteriously as they had arrived, the pilchards began to recede. “They just kept farther and farther out to sea until they disappeared altogether,” recalled Mike Hamilton.

In his book Bull of the Woods, Gordon Gibson described the final season:

The famous sealing schooner Favorite returned to Clayoquot Sound just as the pilchard era began. After the fur seal trade ended in 1911, she had been used as a workshop in Victoria, but in 1916 former sealing captain George Heater took her out of mothballs, rebuilt her interior, and towed her to Sydney Inlet at the north end of Clayoquot Sound. Dismasted, she provided accommodation for some twenty young women Heater brought out from Aberdeen, Scotland, to work at his saltery and fish bait plant. The women set to work salting herring and later pilchard, though that fish had too much oil for the salting process to be entirely successful. The girls’ presence attracted immediate attention from the bachelors in the area, as Mike Hamilton noted. As the telegraph lineman for the area, Hamilton frequently stayed at a cabin in Riley’s Cove, not far from Heater’s enterprise. “A company of girls,” he wrote, “…incurred considerable excitement and fun in that far flung outpost.” The girls likely inspired the name given to the site of Heater’s saltery near the head of Holmes Inlet: Pretty Girl Cove. In 1920, left unattended, the Favorite sprang a leak in a fierce winter storm, which also destroyed the large floathouse, various rafts, and the saltery shed. The remains of the once famous schooner still lie at the bottom of Pretty Girl Cove, her final resting place on the coast she had served so long and so well.

During the dying years of the fur seal hunt, another West Coast industry began to make its presence felt in Clayoquot Sound. In 1909, the Directory of Vancouver Island described the area around Clayoquot in detail, ending with: “This is...a supply centre for whaling and sealing schooners.” By 1909, commercial whaling on the coast had begun in earnest, although in its earliest form it dated back to the 1830s. Then, whaling ships from the eastern seaboard of the United States sailed round the Horn to hunt sperm whales in the Pacific Northwest. By 1834, enough whaling ships were hunting off the West Coast that the Hudson’s Bay Company governor, George Simpson, briefly considered making plans to provision them.

In 1869, Captain James Dawson joined forces with Captain Abel Douglas to form the Dawson and Douglas Whaling Company, setting up whaling stations at Whaletown on Cortez Island and at Whaling Station Bay on Hornby Island in the Strait of Georgia. The company hunted humpback whales for their oil, which it sold to the logging industry. Within three years, Dawson and Douglas fell into insolvency because of a scarcity of whales in the confined strait. In 1904, Captains Sprott Balcom and William Grant formed the Pacific Whaling Company to hunt whales off the west coast of Vancouver Island, establishing a whaling station at Sechart in Barkley Sound in 1905, and a second station at Cachalot in Kyuquot Sound in 1907. Their third station, at Page’s Lagoon near Nanaimo, halted operations in 1908 because of a lack of whales.

Initially, the company hired experienced whalers from Norway and Newfoundland, a fact noted by Father Charles Moser, who visited the Sechart whaling station in June 1906, where he met “nine Catholic men from Newfoundland [who] are employed and engaged to instruct westerners [in] the whaling business.” The company also hired former sealing captains, including Captains Bill and George Heater, to take command of the new steam-driven, harpoon-firing whale catchers. Within two years, and with profits growing, Balcom and Grant formed the Queen Charlotte Whaling Company and opened two more stations at Rose and Naden Harbours in Haida Gwaii. That year, their four whaling stations processed a total of 1,624 whales.

Each plant hired scores of workers, many of them Chinese, Japanese, and Indigenous, to flense and render the carcasses. The sheer volume of whale products emerging from these whaling stations beggars description. Shipments of up to 1,100 barrels of oil at a time from Cachalot and Sechart would arrive in Victoria aboard the steamer Tees, along with vast quantities of fertilizer, mostly destined for international markets in Glasgow, San Francisco, and Japan. According to the Colonist, on September 14, 1905, during Sechart’s first season, the steamer Queen City expected to carry “100 tons of guano [fertilizer] and 300 tons of whale oil” on her next trip down the coast.

The plant at Cachalot employed up to 200 men, half of them Kyuquots who lived with their families in small houses supplied by the company. In later years, Cachalot began processing and canning the whale meat, dubbed “sea beef,” for domestic and Japanese markets. At times of full production, up to 2,000 cases of meat emerged from the plant each day. Father Charles Moser’s diary mentions receiving one of the first cases of canned whale meat from Kyuquot in July 1918; subsequently, the school received canned whale meat on several occasions.

The whaling industry on the coast slowed down around 1909, and the following year Balcom and Grant, whose fortunes remained tied to the dying fur seal trade, sold out to railway magnates Mackenzie and Mann for $1 million. The industry rebounded, only to suffer another setback in 1913, given the glut of whale products on the international market. Two years later, with World War I underway, and aware that whale oil could be used to make explosives, William Schupp bought the company in 1915, renaming it the Victoria Whaling Company. Within a short time, Schupp showed profits of over $1 million annually. Whalers and processors raked in bonuses throughout the war, but the following two decades proved leaner, as the number of whales diminished. Sechart ceased operations in 1917, and the Cachalot plant at Kyuquot closed in 1925.

Between 1908 and 1923, these two west coast whaling stations processed over 5,700 whales. Bizarrely, during their years of operation the whaling stations became a significant tourist attraction on the coastal steamer route. Passengers and crew would disembark for a quick tour, keen to view the great piles of bones and baleen and eager to be photographed alongside the immense carcasses awaiting flensing. Mr. H. Brodie, the CPR inspector touring the coast in 1918, could not comprehend this, appalled as he was by “the most indescribable stench [that] prevails at the whaling station…and makes a large number of people very ill.”

The Rose Harbour and Naden stations in Haida Gwaii continued operating until 1942 when, due to wartime restrictions on travel and the loss of the Japanese market for whale meat, the industry became less viable. In 1948 the Western Whaling Corporation, owned by the Gibson Brothers, established a whaling plant at the old Royal Canadian Air Force station at Coal Harbour, at the northern end of Vancouver Island. Later acquired by BC Packers and a Japanese company, the plant largely processed oil and fertilizer, as well as whale meat for the Japanese market. It remained in operation until 1967, when processors hauled the last whale taken in BC waters up its slipway. By then, Russian and Japanese whaling fleets, equipped with large factory ships to process the whales, were operating offshore and continued to do so until 1975. British Columbia’s whaling industry could not begin to compete. With its antiquated ships in need of replacement, with prices falling, and with the whale population diminishing, commercial whaling came to an end on the West Coast.

By the late twentieth century, few if any observers on the west coast of Vancouver Island shared coastal trader Hugh McKay’s mid-nineteenth-century optimism about the potential of the coastal fishery. As McKay indicated in 1859, fish of many types could be “taken in shiploads” from the waters so “alive with fish.” No longer. Since McKay’s time, fishing fleets had harvested enormous, unsustainable quantities, leaving the fishery in dire straits. Fish stocks declined so precipitously that between 1995 and 1997 the Mifflin Plan, put in place by the federal government’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans, bought back half the commercial fishing licences on the West Coast in an attempt to remedy the situation. This plan reduced the fishing fleet by half and made commercial licences so expensive that only the owners of very large fishing vessels, capable of catching huge numbers of fish, could afford them. The plan did not, however, significantly reduce the number of fish being taken. Stocks continued to decline. Fewer and fewer commercial seine boats plied the waters around Clayoquot Sound.

Thrown out of work, some of the former fishermen opened sport fishing enterprises, or became fishing guides. In Tofino, as in other locations once dependent on commercial fishing, sport fishing gradually evolved during the 1990s to become an integral part the economy—by the 2010s it involved dozens of local outfits and guides. On February 11, 2013, the Vancouver Sun reported that “British Columbia’s recreational fishery is worth as much to the provincial economy as commercial fishing, aquaculture and fish processing combined.”

By 2009 the fleet of BC-based trollers, that had numbered 1,800 in the mid-1990s, dwindled to some 160 trollers fishing the mid-West Coast, following the reductions of the Mifflin plan. That same year, the ten-year Pacific Salmon Treaty signed between Canada and the United States saw numbers decline even more. That treaty saw Canada receive $30 million compensation when it agreed to a 30 percent decrease in the number of chinook (spring) salmon caught by Canadian trollers, in an attempt to protect the fish stocks returning to Washington and Oregon rivers. These catch limits led to the Victoria Times Colonist (December 17, 2009) reporting that “this coming fishing year [will] provide enough fish to support 15 to 30 troll boats in the 160-license fleet.” The newspaper was quoting Kathy Scarfo, president of the West Coast Salmon Trollers Association, who later commented to the Globe and Mail (March 13, 2009), “The days of looking at a harbour and seeing it full of salmon trollers are over.”

The future of West Coast fishing remains highly uncertain. Climate change and shifts in water temperature affect the migration paths of salmon, while sea lice and diseases spread from salmon farms further diminish wild salmon stocks. Meanwhile, conscientious groups valiantly continue to repair spawning streams damaged by logging and other industries, hoping for better days ahead. In 2014, the First Nations in Clayoquot Sound won a landmark Supreme Court decision giving them the right to catch and sell fish commercially, and as consultations continue, First Nations look set to play a far bigger role in the future of the Sound’s salmon, the fish that has sustained them for millennia.