Chapter 8: Along the Pathway to Canada (1866–71)

The pathway that the Colony of British Columbia took to Confederation with Canada in 1871 was neither even nor straightforward. While the notion of Confederation had been around, there was no guarantee of its success. As the previous chapters have pointed out, the path to Canada was littered with obstacles having to be overcome or bypassed.

Overland dreams

The two far west British colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia had, early on, rarely looked beyond their borders. Governor James Douglas had been an exception of sorts with his desire to attract sturdy English folk from wherever they came, albeit with little success given the distance.1

The possibility of an overland route across North America was on some minds. As early as 1862, Douglas strategically informed the Colonial Office how he had looked to “overland communication with Canada by a route possessing the peculiar advantages of being secure from Indian aggression, remote from the United States Frontier, and traversing a country exclusively British.” Douglas went so far as to cost out the length of time and means of travel across the westernmost sections of such a route as of 1862:

| Victoria to Yale or Douglas | 2 days | Steamer |

| On to Lillooet or Lytton | 2 days | Stage coach |

| On to Alexandria | 4 days | Stage coach |

| On to Fort George | 2 days | Steamer |

| On to Tête Jaune Cache | 5 days | Steamer2 |

Explaining that parts of the route were already contracted out with “the assistance of a Government loan,” Douglas described a “proposed line of intercommunication with Red River and Canada” based on trips he had made in the fur trade.3 Douglas’s ambition generated a range of supportive and not-so-supportive Colonial Office minutes, along with a private company being “formed for the purpose of forwarding Emigrants through Canada overland to British Columbia.”4 Douglas witnessed the latter on his seasonal autumn trip to the mainland colony later in the same year:

"I encountered in the course of my journey a number of overland emigrants from Canada who came through from Red River settlement by the Tête Jaune Cache route…They suffered a good deal of privation, but did not experience any serious difficulties in the route until they had passed Edmonton, from whence to Tête Jaune Cache appears by their representations to be the worst part of the journey, they are, however, of opinion that a good road may be formed between these points at a very moderate cost.5

"

Douglas hoped that “Her Majesty’s Government deem it a matter of national importance to open a regular overland communication with Canada.”6 He was not alone in his vision. In May 1862 a resident of New South Wales in Australia enquired hopefully of the Board of Trade in London as to “what progress has been made to connect British Columbia with the Atlantic Ports, through Canada by the Lakes and by Railway.”7 The letter having been forwarded to the Colonial Office, Arthur Blackwood minuted summarily on it: “No real progress: only schemes propounded. No attempts at a rail. Most indefinite.”8 What is clear from this exchange is that a rail line, which would win out, was at least in view.

When, during that same autumn of 1862, Anglican bishop George Hills returned from his three-month Cariboo adventure described in Chapter 4, he met on the Enterprise on the way from New Westminster to Victoria “a young man who had just come over the Rocky Mountains from Canada with a party of 130.” As to how the feat was managed: “they left Fort Garry June 7, each contributed 100$ to the general stock…They brought horses to Tete Jaune Cache, but left them with the Indians who undertook to bring them to Kamloops…They were obliged to make a raft on which they came down the Fraser to Fort Alexandria.”9 While preaching later in the year along the east coast of Vancouver Island, Hills met a “Canadian” who by a combination of roads and water “had come over this autumn by the Rocky Mountains from Canada” with “no real difficulties.”10 Hills was ever more aware of how “by & bye when the railroad shd be formed,”11 immigration to the western colonies would thereby increase.

More concrete steps in that direction followed. A government expedition was, as of March 1866, according to the Colonial Office, exploring “the practicality of a route for Road or Railway, through British Territory from Canada to the Shores of the Pacific.”12

The dream was becoming a reality, or almost so.

American proximity

Complementing attention to an overland route to Canada was British Columbia’s proximity to the United States. No outside factor was more ever-present, due both to that country’s location just south of the forty-ninth parallel and to the numbers of Americans arriving with the gold rush or subsequently who, even if they decided to stay, maintained an affinity with their homeland. As early as 1846, American politician William Seward assuredly pronounced in a public speech respecting the future British Columbia how “our population is destined to roll its restless waves to the icy barriers of the north.”13

Among other observers of the course of events was the American consul in Victoria, from 1862, Allen Francis, whose friendship with President Abraham Lincoln had secured him the posting. Francis’s dispatches cheerfully tracked, among other topics of interest, what he perceived as Victoria’s economic decline, including its non-Indigenous population having more than halved by 1869. His biographer Charles John Fedorak attributes Francis’s insights to how his “daily experience put him in contact with many of his compatriots, who had either returned penniless from the gold mines or lost their businesses in Victoria and were returning to the United States.”14

Francis convinced himself that three-quarters of British Columbia’s non-Indigenous population would support joining the United States. “The people, those claiming to be loyal subjects included, are now urging with great unanimity, annexation to the United States,” he reported enthusiastically to US Secretary of State Seward in the spring of 1867.15

Prospecting annexation

An early, if not the earliest, petition urging British Columbia’s annexation may have been influenced by rumblings in the United States that hinted at its annexing most of today’s Canada. A bill calling for the annexation of the entirety of British North America was introduced in the US House of Representatives on July 2, 1866, and while never voted on, it signalled to some what might be. The British Columbia petition responded more directly to the two colonies’ union in September 1866, which some in Victoria saw as unequal by virtue of, for the first time, the mainland being favoured over themselves. While David Higgins of the Victoria Chronicle, a Nova Scotian via the California gold rush, considered annexation “of all the schemes concocted in the brains of political humbugs…the wildest and most ridiculous,” his competitor, Leonard McClure of the Victoria Evening Telegraph, an Irishman who also arrived via California, convinced himself along with some readers that British Columbia’s annexation to the United States would have the support of the Queen should a united body of colonists make a formal request for her to allow it.16 A public meeting held at the end of September attracted, and to some extent coalesced, some three hundred enthusiasts divided between supporters and opponents of annexation. McClure was so disenchanted by the subsequent indecision he returned to California.17

Two competing visions of British Columbia’s future

Early the next year Britain eclipsed the United States, so it seemed in the moment, with respect to British Columbia’s future. On March 29, 1867, the British Parliament passed the British North America Act, joining together the four British colonies of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario, and Quebec into a Dominion of Canada under a parliamentary system of governance modelled on the mother country. The act contained a provision for other British possessions to join at a later date.18

That was not the only perspective in play. On March 30, 1867, a day after the passage of the British North America Act, US Secretary of State Seward purchased the future Alaska from Russia for US$7.2 million in what he considered to be “a first step in a comprehensive plan to gain control of the entire Pacific Coast” extending south to the border with the United States, and so including today’s British Columbia. Seward anticipated Britain would agree to dispense with the British Columbia colony in settlement of claims for having permitted the US South, during the recently concluded American Civil War, to build ships on British territory.19

As described by British Columbia scholar and diplomat Hugh Keenleyside at the annual meeting of the Canadian Historical Association in 1928, when events were still in living memory, or almost so, the toing-and-froing in the two directions got more and more fervent.

"On the whole, English opinion was adverse, rather than favorable to any strong effort to retain British Columbia, and no very grave obstacles would have been opposed to a peaceful transfer to the United States, had this been urged by the colonials themselves. Many considerations of local pride and immediate advantage urged British Columbia towards American annexation. As a state of the Union, local autonomy could be more fully exercised than as a province of the newly formed Dominion of Canada. With the elimination of all trade barriers between British Columbia and the United States, the necessities of life could be obtained more cheaply, trade would be stimulated, and intercourse facilitated. With a population almost equally divided between Americans and British; with Canada far off and little known; with the English homeland unresponsive and apathetic; with a tremendous financial burden and inadequate political institutions; in a physical situation impossible of defence and isolated from the British world; with all these factors urging her forward, the local solution of the difficulties of British Columbia appeared to be found in annexation with her only neighbors—the Western states of the American union.20

"

Some aspects of British Columbia were on the other hand deemed to be superior to the United States, as with how Americans “vehemently upheld slavery,” considering “the world could not go on without it—the race of [derogatory term for Black people] were fit for nothing else,” or so “a talkative neighbour” explained to Anglican bishop George Hills in February 1861, a year after his arrival. So as to convince Hills to her position, she added that she was “really very charitable to others…even to a poor Irishman!”21 And a Cariboo “storekeeper, a Southern American,” told Hills the next year how “he has scarcely met no American in the country who does not sympathize with the South.”22

By this time self-identifying with British Columbia, Hills was not disposed toward Americans, so he reflected in his daily journal in May 1862, following his seven-hour boat trip between Victoria and New Westminster:

"There were many Canadians & Englishmen on board. It was truly refreshing as a contrast to the sad specimens of fallen men we have had hitherto in miners & adventurers from California & the States. The distance from Canada & England is such that we dared hardly expect to have a British population, but supposed we must be content with a large preponderance of the American element of the Californian stamp, ungodly & vicious.23

"

With the passage of time—and exacerbated by the American Civil War extending from April 1861 to May 1865—numerous persons had crossed the border north into British Columbia because they did not want to be part of the United States. As mentioned in Chapter 3, in May 1861, at Saanich outside of Victoria, Bishop Hills came upon “a party of settlers with cattle, waggons & horses on their way to find a settlement.” As to the reason: “They were Englishmen lately arrived from Oregon preferring the old English farmer to the Stars & Stripes. They have been some years in the States, one of them was from Gloucestershire, another from Wales.”24 Early the next year Hills encountered “a family named Tilton who are contemplating residence here” due to his “being a Peace Democrat & of course turned out of office under the new Regime he is regarded as a traitor” for “having Southern tendencies.”25

Hugh Keenleyside, in his address to the Canadian Historical Association, sketched out the position of those in British Columbia who desired union with Canada:

"Not all the settlers in British Columbia, however, were willing to forego their British allegiance, and many there were who preferred union with the Canadian Dominion—could suitable terms be arranged. “No union on account of love need be looked for,” wrote one British Columbian. “The only bond of union…will be the material advantage of the country, and the pecuniary benefits of the inhabitants. Love for Canada has to be acquired by the prosperity of the country, and from our children.”26

"

In other words, many of the colonists were willing, or desirous, to remain within the Empire if some solution could be found for their economic and political troubles.

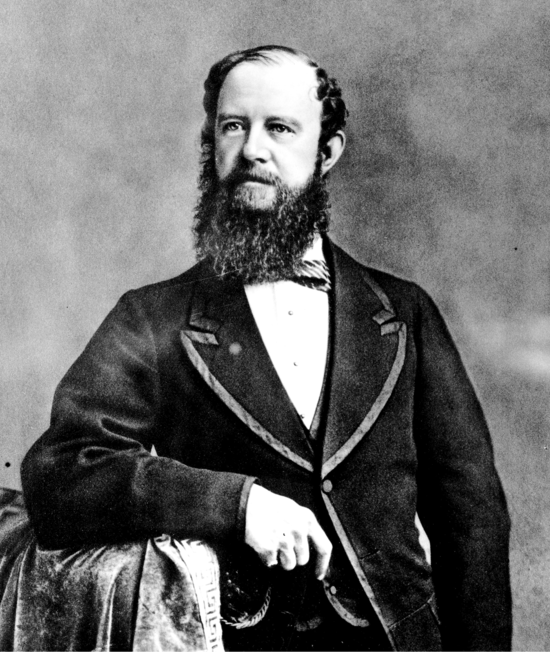

Some others individualized their views about Confederation in a form whose first-hand words survive, as was the case with long-time Vancouver Island physician and colonial politician John Sebastian Helmcken. Helmcken began his memoir in 1892 with the words, “Well, here goes—,” and continued through five notebooks covering 609 handwritten pages.27 His position was a quarter of a century later lodged in his memory:

"I came out against Confederation distinctly, chiefly because I thought it premature—partly from prejudice—and because no suitable terms could be proposed…

Our population was too small numerically. Moreover, it would only be a confederation on paper for no means of communication with the Eastern Provinces existed, without which no advantage could possibly ensue. Canada was looked down on as a poor mean slow people, who had been very commonly designated North American Chinamen. This character they had achieved from their necessarily thrifty condition for long years, and indeed they compared very unfavourably with the Americans and with our American element…Our trade was either with the U.S. or England—with Canada we had nothing to do.28

"

The path to union ran through British Columbia’s Legislative Council, created in the merger, in 1867, of the two earlier colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia. Legislative Council members were of three kinds. The colony’s senior officials, being the colonial secretary, attorney general, treasurer, commissioner of lands and works, and collector of customs, comprised an executive council. The second group consisted of the solicitor general and the eight magistrates posted across the colony at Victoria, Nanaimo, New Westminster, Yale and Lytton, Thompson District, Kootenay West, Kootenay East, Cariboo West, and Cariboo East. The third group was comprised of nine “elected” members, being three from Victoria and one each from Nanaimo, New Westminster, Lillooet, Yale and Lytton, Columbia River and Kootenay, and Cariboo.29 Support for union or annexation waxed and waned depending on who had been elected or appointed.

In 1868, seeking to break the impasse whereby the Legislative Council, controlled by annexationists, stood firm in opposition to union, the Canadian government took charge, acknowledging how it “desires union with British Columbia and has opened communication with the Imperial government on the subject.” The next year the Dominion government took over the rights of the Hudson’s Bay Company to the intervening territory between Canada and British Columbia, and the Imperial government appointed a new governor favouring Confederation.30

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. There would be a few more bumps and twists in the path before 1869 and the new governor.

Hard economic times

In the short term, the immediate consequence of the US purchase of Alaska in 1867 was to box in British Columbia on the north as well as the south at a time when the colony’s economy was floundering. Writing to the Colonial Office in June 1867, Governor Seymour acknowledged a harsh reality: “The finances are, I regret to say, in a deplorable condition…the Colony was, up to the present time kept alive by loans raised in England, on which we have now to pay heavy interest while receiving absolutely no aid of any kind from the Mother country.”31

Writing a month later, Seymour was so agitated he forgot to sign his letter, to the Colonial Office’s righteous indignation. In it Seymour anticipated an annual deficit of £45,000, about which he had “had no idea when in England last year…or else I should have communicated fully with Your Grace’s Department on the subject.” Seymour aptly observed how “it is now for the first time that the Colony has been thrown on its own resources,” having earlier “subsisted to a considerable extent on loans contracted in the Mother Country,” as had been the case under James Douglas’s watch.32

In response to Seymour’s unsigned letter, with its harsh reality check respecting British Columbia’s state of affairs, the Colonial Office’s permanent under-secretary, Frederic Rogers, posed in his minute of September 16, 1867, the fundamental question for the Colonial Office respecting British Columbia’s future.

"This only concerns the past. As to the future it is no doubt true that high taxation, distress and want of assistance from home will probably cause the American population of the Colonies to press for annexation—a pressure wh wd soon become irresistible…On the other hand if the Colonists once find that the annexation threat [is] satisfactory in extracting money from us they will plunder us indefinitely…

I suppose the question to be (in the long run) is B.C. to form part of the U.S. or of Canada; and if we desire to promote the latter alternative, what form of expenditure or non-expenditure is likely to facilitate or pave the way for it.33

"

Parliamentary Under-Secretary Charles Adderley minuted the next day how British Columbia’s future was on the line:

"It seems to me impossible that we should long hold B.C. from its natural annexation. Still we should give & keep for Canada every chance, & if possible get Seymour to bridge over the present difficulties till we see what Canada may do. I think our US Minister should keep his ears open for any overtures of equivalents in exchange of this territory.34

"

Another petition

In July 1867 another petition circulated among dissatisfied Victorians. Intended for Queen Victoria, it gave her a stark choice:

"Either, That Your Majesty’s Government may be pleased to relieve us immediately of the expense of our excessive staff of officials, assist the establishment of a British steam-line with Panama, so that immigration from England may reach us, and also assume the debts of the Colony.

Or, That Your Majesty will graciously permit the Colony to become a portion of the United States.35

"

As with its predecessor, what, if anything, ensued respecting the petition is uncertain.

In his memoir, John Sebastian Helmcken, who was then Speaker of the BC Legislature, recalled about this and subsequent petitions:

"Some Americans privately got up an agitation and tried to persuade the British settlers to petition the President of the United States to use his assistance to have the Island annexed to the United States. Of course the same arguments and persuasions were used then as since, that it would be for the immediate and permanent benefit of the Island, that all would become rich. They pointed out too the fact that HM Govt cared but little about the Colonies and was willing to let them go, an expense they being at this time of Free Trade agitation and success, an incumbrance of defence, and liable to lead the mother country to war or in case of war the cost of defending them. These doctrines were at this time in the ascendant among the Free Traders—who considered that the Colonies only would stick to England, until they became independent like the United States…

Many talked more or less about annexation—and in press of time when the question of Union with B. Columbia and subsequently Confederation came up, doubtless many debated whether it would not be better to be at once annexed instead of waiting until the whole of Canada had been gobbled up—for I think before this the Americans had bought Alaska…

After the Americans bought it they boasted of Canada being sandwiched—ready to be gobbled up.36

"

Helmcken’s biographer points out that, based on his writing, Helmcken was never himself in favour of annexation by the United States, “though for a time he feared that it might be forced upon British Columbia by circumstances,” given it “could not continue to exist for long as a separate entity” due to its “financial and commercial problems.”37 British Columbia hung in the balance.

Seymour cast on his own resources

On September 24, 1867, Governor Seymour reported to the Colonial Office “on the desire of the people of this Colony to join the Eastern Confederation,” as attested by a resolution “passed by the Legislative Council in favour of negotiations being entered into with a view to a union of all the British Possessions in North America.” He was cautious. “Though the motion passed through the Council without opposition, there was but little warmth felt in its favour” owing to uncertainty as to what benefits would ensue, given “the lands intervening between Canada and our frontier belong to a private Company”—namely, the Hudson’s Bay Company.38

Seymour speculated on what was feasible given:

"No immigrants from England now resort to this Colony. The only English men who find their way hither filter to us through California, and as adventurous Americans still visit us the population is now becoming alien to a large extent. It is thought by many of those who have made of this their home, that the only chance of its becoming prosperous while a dependency of a very distant Country…is a union with the more developed and apparently more prosperous Colonies on the Atlantic.39

"

Seymour’s letter highlights his loneliness and his sense of isolation in his distant location.

The American alternative

In the interim, the American alternative continued to beckon. As economic conditions worsened, talk in British Columbia turned openly and explicitly, including in several local newspapers, to the possibility of the colony joining the United States.40 The very day after writing his loneliness letter, a distraught Seymour alerted the Colonial Office, in a letter marked “Secret,” to “the annexation feeling prevalent in Victoria,” to “the absence of all assistance from Home,” and to American troops about “to be poured into Alaska” consequent on “their recent purchase to the North of us.”41

If Seymour was taken up with the American factor, so to a considerable extent was the Colonial Office. A minute of November 6, 1867, on Seymour’s September 24 letter respecting the Legislative Council’s lukewarm support for Confederation might have changed some minds respecting the Hudson Bay Company’s role in the course of events. Frederic Rogers put in its necessary order what needed to happen: “It did not appear to H.G. [His Grace, the secretary of state] that any practical steps could be taken in the matter while the Colony was separated from Canada by so large a tract of unoccupied Country, at present in the possession of a private Company.”42

Seymour continued to update the Colonial Office on what he similarly considered to be a crisis situation. Writing on December 13, 1867, he virtually begged for “a temporary loan from the Mother Country” to offset the need for “$223,000 dollars more than we shall possess to meet existing liabilities.” Pointing out how, “with the enormous attractions of California close to us,” the colony “cannot greatly increase the taxation without driving out the remaining portion of the population,” Seymour reminded the Colonial Office that “when the Gold in Fraser’s River was first discovered there was a great rush to the Colony from California and Australia” of “between 12,000 and 13,000 men,” whereas currently “between Hope and Yale…not more than half a dozen Chinamen were now the sole workers.” Everyone was stretched, including himself. “My own salary is nine months in arrears.”43

Five days later in faraway London, Colonial Office senior clerk William Robinson, following his close dissection of British Columbia’s situation, confirmed to the others that “the finances are in a most embarrassed state, that the Colony is paying heavy interest & sinking fund on Loans contracted in England, that it is largely indebted to the Colonial Bank, to the Crown Agents, to some of its public officers, & that the Salaries of the Public officers are several months in arrears.”44

Better news at hand

A year later, in August 1868, Seymour permitted himself a touch of optimism. On reading seasonal reports received from the three magistrates under his purview based in the far distant Cariboo, he wrote, “It really seems as if British Columbia is to become a settled Colony at last instead of a mere gold field with an unattached population.”45 Peter O’Reilly had reported from Yale:

"The district under my charge is in a very satisfactory state, the best possible proof of which is the increase of permanent settlement and the quantity of land that has been taken up, forty six preemption claims having been recorded by me within the last year.

These farms are not held for the purpose of speculation but have been stocked and put under cultivation, the pre-emptors being stimulated by the success which has attended the older settlers. Crops of all kinds throughout the district are looking remarkably well, and promise large returns. Hitherto the want of a flour mill has been much felt in the neighbourhood of Kamloops, but through the energy of Messrs. Fortune and McIntosh a good mill has been erected at the mouth of Tranquille River, which will prove a great boon to the settlers in that section of Country, and will lead to a much larger extent of Land being put under cultivation than has hitherto been the case.

Cattle have largely increased in numbers, and over four thousand sheep passed through Yale in the last two months, most of which are intended…for the Bonaparte and Nicola districts.46

"

O’Reilly described how “the banks and bars of the Fraser River continue to be worked by Chinamen, of whom there are about four hundred in the district; their average earnings being from two to four dollars per day to the hand,” with the mining population overall “each year being more and more concentrated in Cariboo.”47

As for access, “the portion of the waggon road now under my supervision extending from Yale to Clinton is in excellent order” so that “large quantities of good have been forwarded over it principally by the Hudson’s Bay Company for their posts on Similkameen, Fort Shepherd, and Colville, and also by the settlers from the Southern boundary to the Head of the O’Kanagan Lake.”48

Writing on August 5, 1868, E. Sanders, magistrate of the Lillooet district, described how out of 104 miners at a dozen locations,

"but few are whites, the remainder it is needless to state are Chinese, to these may be added a few Indians, who although not given to mining with persistency, do spasmodically take to gold seeking, more particularly in spring and late in autumn when the waters of the Rivers are at their lowest, thus contributing to some modest extent to the enrichment of the Colony…It is most difficult to ascertain with the least degree of accuracy what amount represents the average earnings of Chinese miners, but I am inclined to think it may be safely estimated at from $4 to $5 a day. Last year the total gain of gold in the district was valued at $50,000oo.49

"

Sanders concluded on a note very similar to that of O’Reilly as to how everyday landscapes were changing:

"The settling up of the Land in the district has progressed beyond expectation during the present year. Since January not less than 6080 acres have been taken up and occupied, and I have every reason to believe that the great majority of the preemptors are bonâ fide settlers, men who are likely to till and render their claims productive by the coming spring. The crops everywhere, despite the scarcity of water for the purposes of irrigation are more than usually abundant this year and harvesting in the vicinity of Lillooet at least has been in progress since the 20th of last month. Farmers I am rejoiced to say are as a rule well to do and satisfied, their prospects are not only bright but brilliant, the conviction seems to be gaining ground amongst them that few Countries afford equal, much less superior advantages to the industrious, thrifty, agricultural than this. And the realization of the chief wish of those who have the interests of the Colony at heart, namely that its valleys and broad table lands might be settled up by a permanent white population, seems at last after a tedious waiting of many years to be within the range of the possible.50

"

A similar report of August 26, 1868, from Henry Maynard Ball respecting “the state of the New Westminster District, since October 1867,” when he took charge of it, reads much the same respecting changing times and growing commitment to the physicality of British Columbia:

"A District possessing such an extent of agriculture and grazing resources has naturally attracted the attention of many who having led a wandering life during the early years of their residence in the Colony are anxious to settle down and carve out for themselves from the waste lands a more permanent home, and numerous preemption claims have been taken up in the District extending from the Chilliwack and Sumas Rivers to the Sea Coast.

The number of new claims preempted, since October amounts to Twenty eight, but I should mention that there are many old established Farms within the limits I mentioned, whose owners are well off and comfortably settled…

The Chilliwhack District possesses by far the finest land and would be more popularly settled were it not cut up and occupied by the Indian reserves. Of them there are fourteen within a circuit of Thirty miles, containing patches of some of the best land. Each Indian tribe has a reserve on which potatoes and other vegetables are grown, and over which their pigs and cattle roam.

It would be impossible and would not be politic to attempt to concentrate them on one large reserve, as the different tribes although speaking the same language are ruled by separate petty chiefs amongst whom much jealousy exists. Up to the present time there has been but little conflict between the White settlers and the Indians, many of the latter being frequently employed as labourers by the farmers.

On the Banks of the North Arm of Fraser River there are about 14 settlements…As a proof that a hard working and industrious man may in a few years make a comfortable home for himself, I may mention one instance. That of a French Canadian named “Garipee” on the North Arm. In 1864 he preempted a piece of Land, commencing with a sack of potatoes and an axe. He now possesses 18 cows, 2 work oxen, a good house, pigs & chickens with 8 or 10 acres under cultivation & fenced, all acquired through hard work and industrious habits.51

"

Ball went on to describe a steam flour mill at New Westminster that “will now give a new impetus to farming operations in the neighbourhood and offer a good and profitable market for their produce.” He added, “The trade of the town of New Westminster is supported partly by the settlers of the neighbourhood, the lumberers at Burrards Inlet, and partly by the Indians who are large consumers of certain articles.”52 As for the site of the future Vancouver: “I must now turn to what I consider the most important portion of the District viz Burrard Inlet and the Lumber Interest. At present there are about 320 men engaged at the two Mills and the different logging camps around the Bay…I have seen as many as 10 ships in the Bay loading and waiting for cargoes at the mill.”53

What is clear from these observations is that British Columbia was, by the mid-1860s, more energetic and diverse than perceived by the small minority who had arrived in Victoria early on and exercised power at the political level.

The Legislative Council in action

In the spring of that year, April 1868, the Legislative Council passed a resolution favouring “the general principles of the desirability of the Union of this Colony with the Dominion of Canada.”54 In line with the resolution, in September “a large and respectable Public meeting,” sometimes termed a convention, was held at Yale in the Fraser Valley, where those in attendance agreed on “Union or Confederation with the Dominion of Canada,” on “Representative Institutions and Responsible Government,” on “retrenchment in the Public expenditure,” and on “a reciprocal commercial treaty with the United States.55

Reporting to the Colonial Office at the end of November, Seymour cautioned that “the proceedings of the Yale Meeting did not meet with universal approval” and that “the more prominent advocates of Confederation were defeated at the last elections in Victoria for members to serve in the Legislative Council.” Seymour also pointed out the Yale convention’s distinctiveness:

"Local politics have their Head Quarters in Victoria. If one ascends the Fraser but a few miles one finds less excitement and better tempers at New Westminster and so it goes on in proceeding up Country till at Clinton the whole thing is ignored. The miners of Cariboo and Kootenay are in the most profound state of indifference as regards what is passing at Head Quarters.56

"

Taking the Yale proposal seriously as a possible turning point, Frederic Rogers, the permanent under-secretary, was cautiously optimistic in his minute on Seymour’s letter:

"It seems to me questionable whether V.C.I. can be conveniently governed from Ottawa. But if the parties concerned think it can, it is certainly not for the British Govt (I shd say) to stand in their way. Our policy, I should say, was to assist everything wh tends to make Union practicable, but to discourage that premature & impatient action wh defeats its own object so far as we can witht appearing to resist that wh (I presume) we really wish to see effected.57

"

Rogers was well aware that “the present state of the negotiations with the HBC wh renders it for the moment absurd to talk of Union betn Canada & B.C. is both a real & a producible reason for not entertaining the question now. And I wd so use it.” Rogers set forth some cautions, among them:

"

- That formally represve institutions did not answer very well in V.C. Island.

- That they will almost certainly hasten the course of Anglo-Saxon violence ending in destruction of aborigines. For the purpose of keeping the peace in this respect the American character of the population renders the maintenance of an Executive responsible to an external authority particularly necessary.

- There is a great practical difficulty in either providing for the representation of aliens & miners (who form a large part of the population) or in leaving them unrepresented…

In short I submit, that this Colony is not in a state to be relieved from a certain steadying external pressure—& I do not like to relieve it from the pressure of Downing Street [in London] till we can substitute the pressure of Ottawa.58

"

Time would tell, Rogers acknowledged, whether “the ‘Convention’ is mere empty blast” or something more.59

On December 17, 1868, Governor Seymour opened a new legislative session with a sense of optimism, reporting to the Colonial Office: “As far as I can judge I think that the people and their representatives are in a better temper than I have seen them for some years,”60 adding, in his address to open the session, how “the Public debt has been considerably reduced yet larger sums have been expended on public works of utility.”61 The good mood continued into the new year, and he telegraphed the secretary of state for the colonies on January 20, 1869, as to how “there is an improvement in the Revenue, the Legislative Body is in Session and that everything is tranquil.”62

A month later Seymour alerted the new secretary of state for the colonies, Granville Leveson-Gower, Earl Granville, as to how “we are anxiously working through a period of intense depression. But I think that when the railroad is made across the continent British Columbia will recover to a certain extent her former prosperity.”63

The most contentious business of the session came on February 17, 1869, when the Legislative Council passed a resolution reading:

"Resolved

That this Council impressed with the conviction that under existing circumstances the Confederation of this Colony with the Dominion of Canada would be undesirable, even if practicable, urges Her Majesty’s Government not to take any decisive steps towards the present consummation of such Union.

William A.G. Young

Presiding Member64

"

Seymour, who was not best pleased by the resolution being “antagonistic to the immediate consummation of such a measure,” sent it on to the Colonial Office on March 4, 1869.65

However, by the time Seymour closed the session with a speech a week and a half later, he was in high good humour. “I found the Legislative Council in an obliging, conciliatory humour, while disposed to take more of initiation than usual. A good sign, of course, for the working of our present Constitution; I have carried all the Bills to which I attached importance.”66

Come June 1869 the situation had further improved. The confidential dispatch the secretary of state for the colonies sent Seymour on June 2 speaks for itself:

"I have the honor to transmit to you a Copy of a Confidential Dispatch from the Governor General of Canada suggesting at the instance of his Ministers that steps should be taken to forward the incorporation of British Columbia into the Dominion of Canada…

You are aware that the Hudson’s Bay Company have accepted the terms recently offered to them for the surrender of their Territorial Rights to the Crown and that in the event of the arrangement being accepted by the Canadian Government there is every prospect of the annexation of the Hudson’s Bay Territory to Canada.67

"

Frederick Seymour sadly did not live to read this news. Already in “a delicate state of health, suffering from extreme debility,” yet persisting, Seymour died just over a week later, on June 10, 1869, at Bella Coola on board HMSSparrowhawk while on a tour of inspection along the northwest coast of British Columbia.68 Philip Hankin, the colonial secretary, was sworn in as acting governor.

Hankin was left to reply to a Colonial Office letter asking Seymour for specifics respecting the February 17 resolution against Confederation. “The late Governor left it entirely an open question as to the manner in which each official Member should vote.” He explained how “the Majority which passed the Resolution against Union consisted of eleven Members, only five of whom were connected in any way with the Government,” whereas “the Minority, in favour of Union, were Messrs Havelock, Humphrey’s, Carrall, Robson and Walkem, the last three named Gentlemen natives of the Dominion.”69 Henry Havelock was from Yale; Thomas Humphreys from Lillooet; William Carrall, Cariboo; John Robson, New Westminster; and George Walkem also Cariboo. The first four were among the Legislative Council’s eight elected members; Walkem one of the thirteen appointed members. As the Colonial Office may have noted, none of those favouring Confederation were from Vancouver Island. Hankin’s concluding sentence took a broader perspective: “It appears to me to be the general opinion that until communication through British Territory is established those who are most interested in the welfare of British Columbia will be opposed to Confederation.”70

A new governor

By the time of Frederick Seymour’s death in June 1869, the Colonial Office had already laid the groundwork for a successor. Among a host of hopefuls, not surprising in a milieu where Colonial Office appointments were much sought, was the ever-ambitious Colonel Moody, who, writing just a week after Seymour’s death, described himself as “entirely unoccupied and free for any duty.” His letter was summarily minuted: “Answer already filled up.”71

A June 16 telegram sent to Philip Hankin read: “Mr. Musgrave is appointed Governor. You may announce that he will proceed to British Columbia immediately.”72

Anthony Musgrave was, like his predecessors, a career administrator. Born in the West Indies, where his grandfather, father, and then he himself had held office, Musgrave had governed Newfoundland prior to being named to British Columbia on Seymour’s death. His crossing to the western colony by rail via New York and San Francisco to take up his new position as of August 23, 1869, abolished any hesitations he might have had about the advantages of that means of transportation.73

A critical breakthrough

A critical breakthrough came on August 14, 1869, initiated by a letter from the secretary of state for the colonies, Earl Granville, informing Musgrave that the terms on which the intervening Hudson’s Bay Company territory was to be “annexed to the Dominion” had been agreed and the larger decision was now at hand:

"The Queen will probably be advised before long to issue an Order in Council which will incorporate in the Dominion of Canada the whole of the British Possessions on the North American Continent, except the then conterminous Colony of British Columbia. The question therefore presents itself, whether this single Colony should be excluded from the great body politic which is thus forming itself.

On this question the Colony itself does not appear to be unanimous. But as far as I can judge from the Despatches which have reached me, I should conjecture that the prevailing opinion was in favor of union. I have no hesitation in stating that such is, also, the opinion of Her Majesty’s Government…

The establishment of a British line of communication between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, is far more feasible by the operation of a single Government responsible for the progress of both shores of the Continent than by a bargain negociated between separate, perhaps in some respects, rival Governments and Legislatures.74

"

Not only that but, in what was an interesting acknowledgment from the Colonial Office, Granville wrote:

"The constitutional connection of Her Majesty’s Government with the Colony of British Columbia is as yet closer than with any other part of North America, and they are bound on an occasion like the present to give, for the consideration of the community and the guidance of Her Majesty’s Servants, a more unreserved expression of their wishes and judgment than might be elsewhere fitting.75

"

From the Colonial Office’s perspective, British Columbia mattered in a special kind of way, including, as the letter noted “the condition of Indian tribes,” making it important that those in charge “take such steps as you properly and constitutionally can, for promoting the favourable consideration of this question.”76

Governor Musgrave’s task was set.

Musgrave in charge

Incoming governor Anthony Musgrave’s first order of business, as soon as possible on his arrival in the summer of 1869, was, like his predecessor, to visit the principal settlements, in this case New Westminster, Yale, Lytton, Williams Creek, Cariboo, Clinton, Lightning Creek, and Quesnelmouth. One reason for doing so was to clear up uncertainties left behind by an ailing Seymour; the second to collect “information on the state of feeling with regard to Confederation and other matters.”77

Musgrave’s main task was to convince officials in the localities to support entry into Confederation by assuring them union with Canada would not deprive them of their livelihoods. It was, Musgrave reported to the Colonial Office in August 1869, “the chief topic of interest.”78 Returning to Victoria in mid-October, Musgrave described those he had encountered in his travels as being “almost without exception prosperous,” with businesses of all kinds being built on stable foundations, agriculture “being pursued to a greater extent with much success,” and stock farming growing in importance.79

Writing on October 30, 1869, following his return to Victoria from his trip familiarizing himself with the province, Musgrave laid out for the Colonial Office the potential roadblocks he envisaged on the pathway to Confederation in respect to “the total white population in both sections of the United Colony,” which “does not amount to ten thousand,” of whom “more than half are resident in Vancouver Island, principally at Victoria.” In what had earlier been James Douglas’s criteria for belonging or not so, Musgrave differentiated, without explaining why, how “a very large proportion both here and on the Mainland, are not British subjects, and not unnaturally would lean rather towards annexation to the United States,” even though “they live contentedly enough under what they admit to be an equitable government, in which the laws are fairly administered.”80

Respecting the assumption held in Canada that in British Columbia “there is a very general desire for Union, and that opposition is almost entirely confined to Official Members of the Council,” seeking “provision for their retirement on suitable Pensions, or at least that they should have the option of so retiring,” Musgrave saw no reason not to replicate in that respect in British Columbia what had been “done on the introduction of Responsible Government in the Eastern Provinces” of Canada.81

From Musgrave’s perspective, “the more prominent of the Agitators for Confederation are a small knot of Canadians who hope that it may be possible to make fuller representative institutions and Responsible Government part of the new arrangements, and that they may so place themselves in positions of influence and emolument.” The “mercantile portion of the Community” sought “to secure in terms with Canada that Victoria should be made a Free Port.” In sum, “there is great diversity in the views entertained upon this important question.”82

Musgrave went on to share his private views on several aspects of Confederation. Respecting the outstanding question of “the introduction of ‘Responsible Government’ in the local administration after Union,” it was Musgrave’s “opinion that it would be entirely inapplicable to a Community so small and so constituted as this—a sparse population scattered over a vast area of country.” And he fretted over financial matters:

"The liabilities of this Colony are very heavy, and the population is very small…The machinery of government is unavoidably expensive from the great cost of living, which is at least twice as much as in Canada, and the great area over which the action of government must be maintained for a small number of residents…the grant in aid under the British North America Act 1867 to the other Provinces, of 80 cents per head to the population, would amount only to an insignificant sum in our case.83

"

While, as instructed, Musgrave had printed in the Victoria newspaper the government’s dispatch “respecting the Union of this Colony with the Dominion of Canada,” he was waiting until the Legislative Assembly met in December to lay it before that body.84

The Colonial Office minutes on Musgrave’s letter of October 30, 1869—which Musgrave of course never saw—bode well for British Columbia’s future. Frederic Rogers, the permanent under-secretary of state for the colonies; Earl Granville, secretary of state for the colonies; and William Monsell, parliamentary under-secretary of state for the colonies, decided they would encourage Musgrave “to use his own judgment respecting the mode & time of bringing the question before his Council—and not to suppose himself bound to bring forward any formal proposition, unless he thinks that by so doing he will promote further the acceptance of the Union.”85

In early 1870 Musgrave managed the feat by, he explained to the Colonial Office, not forcing “Confederation upon the Community without time being afforded for consideration,” and “by putting the proposal before the Community in an intelligible form.”86

A final lunge for British Columbia joining the United States

A final American lunge for British Columbia now came into play, making the rounds of the highest levels of government in Britain and the United States. A petition, prompted by “the avowed intention of Her Majesty’s Government to confederate this Colony with the Dominion of Canada,” beseeched the American president “to endeavour to induce Her Majesty to consent to the transfer of this Colony to the United States” (italics in original).87 Signed by seventy property holders, businessmen, merchants, and others in Victoria, Nanaimo, and elsewhere on Vancouver Island, “many of us British subjects,” the petition was presented to President Ulysses S. Grant on December 29, 1869, by “the special Indian Commissioner for Alaska Tribes,” who had been passing through Victoria on his way to Washington, DC, and agreed to take it with him.88 As indicated by their surnames, and biographical information prepared by historian Willard Ireland, petitioners included numerous shop owners of German or other non-British descent.

On January 3, 1870, Sir Edward Thornton, the British minister to the United States, sent the Earl of Clarendon, secretary of state for foreign affairs, a copy of what he referred to as a “Memorial,” which had been brought to Washington “by an American Citizen, Mr. Vincent Colyer,” a Quaker who had “recently paid a visit to Alaska for the purpose of inquiring into the condition of the Indians in that territory.” The memorial had been delivered to the President on December 29, accompanied by a request that he would “not only submit it to his Cabinet but would also send it to the Congress.”89

Thornton’s January 13 letter explained how the memorial delivered by Colyer fit in with larger events in play in Britain’s North American colonies. He pointed to an “existing disturbance in the Hudson’s Bay settlement, and the asserted disaffection in Nova Scotia,” along with “differences arising with [Britain] out of the ‘Alabama’ affair” consequent on Britain having permitted the South to build merchant ships on its territory during the recently concluded American Civil War. From Thornton’s perspective as the British minister to the United States, and on his reading of the American press, these events were “looked upon as the beginning of a Separation of the British Provinces from the Mother Country, and of their early annexation to the U.S.” In this view, “England has it in her power, and might not be unwilling, to come to an amicable settlement of these differences on the basis of the cession of our territory on this Continent to the United States.”90

Events cascaded. Three days earlier, on January 10, 1870, Oregon senator Elijah Corbett, referencing the Colyer memorial, presented a resolution in the United States Senate “that the Secretary of State should inquire into the expediency of including the transfer of British Columbia to the U.S. in any Treaty for the adjustment of all pending differences between the two Countries” related to British actions during the American Civil War.91

Events did not play out as former Secretary of State William Seward had predicted. He had assumed Britain would acquiesce to British Columbia’s annexation to the United States, thereby getting the Civil War claims off its hands, but not so.92 The United States pulled back in the face of the Colonial Office’s support for British Columbia’s union with Canada, facilitated by the Hudson’s Bay Company’s relinquishment of the intervening territory lying between British Columbia and British colonies to the east.

Support and opposition in the Legislative Council

Musgrave was able to forward to the secretary of state for the colonies on February 21, 1870, “Copies of the Resolution which it is proposed to pass embodying the terms on which this Colony would be willing to join the Dominion.” As he noted on the letter, “it now remains to be ascertained to what extent the Government of Canada can fulfill the expectations of the Colony.”93 There had been, Musgrave pointed out two days later, trade-offs on the part of British Columbia, with “suffrage limited to British subjects” as opposed to “universal suffrage including foreigners” which “if allowed to continue would very probably defeat Confederation.”94

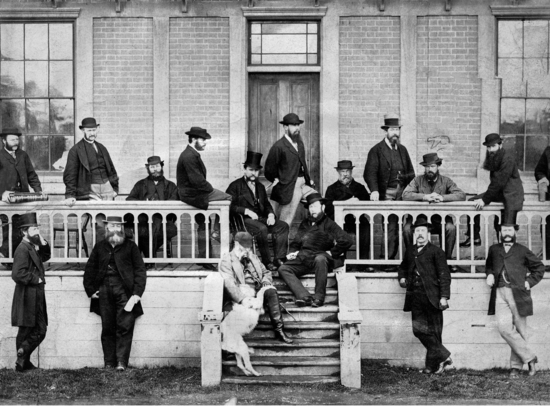

The debate of the colony’s Legislative Council, which comprised nine elected and six appointed members, on “Confederation with Canada” began on March 9 and ended 100,000 words later on April 6, 1870, with the simple statement in the minutes, “House adopted resolution.”95 Musgrave thereupon reported to London how the Legislative Council had passed all of “the Resolutions which were submitted to them on the subject of Union with the Dominion of Canada,” with some suggestions for “modifications in the proposed terms” and “supplementary recommendations” relating to “the peculiar circumstances of this Colony.” As requested of him, Musgrave had “succeeded in avoiding the introduction of proposals touching on ‘Responsible Government’ or the establishment of a Free Port,” both potentially contentious issues.96

Musgrave was not optimistic about achieving a rail line, and for that reason proposed “to send a delegation to Ottawa to present the proposals,” and to discuss and explain them. The delegation comprised “Mr Trutch, the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works,” in “whose ability and discretion” Musgrave had “much confidence”; Mr Helmcken, who had “great influence in the Community” despite being “far from…an ardent Confederate”; and “Mr Carrall,” who was “a Canadian and a zealous advocate of Union,” and also “familiar with the wants and views of the people of the Upper Country.”97

The delegation’s negotiations with the federal government were successful, Canada agreeing to build the essential railway linking British Columbia eastward across North America. By November Musgrave was feeling particularly optimistic, daring to close a letter to the new secretary of state for the colonies, John Wodehouse, First Earl of Kimberley: “it seems now probable that very little time will elapse before British Columbia becomes part of the Dominion of Canada.”98

Public pensions

Before the deal could be signed and delivered, however, agreement also needed to be reached on “the future position of Government Servants as one of those questions requiring some personal care on the part of the Governor.”99 This particularly affected civil servants in Victoria, which continued to see itself as in charge of the order of things. On November 16, 1870, Musgrave reminded the Colonial Office how:

"By the sixth Article of the Scheme of Union agreed upon between the Canadian Ministry and the Delegates from this Government it is stipulated that suitable Pensions such as shall be approved by Her Majesty’s Government shall be provided by the Government of the Dominion for those of Her Majesty’s Servants in the Colony whose position and emoluments derived therefrom would be affected by political changes on the admission of British Columbia into the Dominion of Canada.100

"

Just in case they were not individually known to the Colonial Office, Musgrave shared the names of “those who will be affected injuriously by the change” with their “salaries inserted in the margin”:

| The Colonial Secretary | Mr Hankin [£800] |

| The Attorney General | Mr Phillippo [£800] |

| The Commissioner of Lands and Works | Mr Trutch [£800] |

| The Collector of Customs | Mr Hamley [£650] |

| The Auditor General | Mr Ker [£500] |

| Stipendiary Magistrates | Mr Ball |

| Mr O’Reilly | |

| Mr Sanders | |

| Mr Bushby | |

| Mr Pemberton | |

| Mr Spaulding101 |

These five officers, along with the six magistrates, embodied, on the one hand, the last stand of the colonial establishment’s governance of the Island colony and, on the other, the entryway to two stand-alone provinces where political power would be more broadly based. Their stories give a sense of who had mattered, and why they had done so.

Arriving as a Royal Navy officer, Colonial Secretary Philip Hankin had been so enchanted by “the social life of Victoria” he resigned his commission in favour of various civilian appointments, in the course of which his “ability to govern” was called into question, but insufficiently so for him to be denied a lifetime pension that accompanied him to England to become private secretary to the Duke of Buckingham, former secretary of state for the colonies.102

Jamaican-born and English-educated Attorney General George Phillippo was appointed attorney general only in 1870, resigning a year later, pension in hand, for a position in British Guinea.

English-born and -educated Commissioner of Lands and Works Joseph Trutch had chased the California gold rush north, reaching British Columbia in 1858, where he worked as a surveyor. He was appointed commissioner of lands and works in 1864, even as he established himself as, to quote historian Robin Fisher, among “the people who ran British Columbia and…ran it in their own interests and those of their class,” with “anyone who stood in the way…likely to get short shrift from Joseph Trutch and his kind.”103

Collector of Customs Wymond Ogilvy Hamley followed a distinguished father into the Royal Navy, but resigned to join the Imperial Civil Service, whence he was offered the colonial position.

Born into “a family long prominent on the Scottish border,” Auditor General Robert Ker came for the gold rush, to be quickly recruited into government service.104

Neither were the five stipendiary magistrates everyday arrivals. They each also have their own stories to tell, excepting Spaulding, about whom no information was found. On retiring after fifteen years in the English army, followed by ten years in the Colonial Service in Australia, Henry Maynard Ball had sought a new experience, to have an intermediary successfully recommend him for “an appointment in British Columbia or Vancouver’s Island.”105 Born in England and educated in Belgium and Germany, Edward Sanders served in the Crimean War prior to being appointed a gold commissioner in Yale in 1859. The son of a London merchant and of a respected linguist and writer of fiction, Arthur Bushby headed off to the British Columbia gold rush in 1858 with a letter of introduction from the governor of the HBC in London, which got him a job as private secretary to Judge Begbie, who he accompanied on his mainland circuit. He married James Douglas’s daughter Agnes and they settled in New Westminster to have five children together.106 Grandson of a lord mayor of Dublin, Joseph Despard Pemberton became an engineer and surveyor, which skills he transferred in 1851 to Vancouver Island.107

In December 1870 Musgrave updated Kimberley respecting the nine members just elected and six appointed to the Legislative Council, whose task Musgrave specified in no uncertain terms: “The business of the Session will be almost entirely limited to completing the proposed Union with Canada…I think that I shall be able to obtain sufficient support even among the elected members to avoid or surmount any complications arising from this cause. All elected Members have been returned in favor of Confederation.”108

Minutes on Musgrave’s letter, all written on the same day by Frederic Rogers; Sir Robert George Wyndham Herbert, assistant under-secretary of state; and Kimberley, retail the Colonial Office’s enthusiastic response:

"He proposes to legislate with the view of paving the way for Responsible Government in the event of, & after, Confederation. RGWH Feb 1/71

I shd wholly trust his judgement in the matter, & shd leave him discretion. FR 1/2

I agree. K Feb 1/71109

"

From the Colonial Office’s perspective, British Columbia was on its way.

Musgrave completing his designated task

Given the obligation Musgrave brought with him to the governorship of British Columbia, it was with obvious relief that he sent a telegram on January 20, 1871, to Kimberley, reading in its entirety:

"Address to Queen for union with Canada on terms agreed upon passed Legislative Council unanimously today.110

"

Senior clerk Charles Cox minuted almost gleefully to the secretary of state on the telegram itself, “This looks like getting to business,” whereas others in the office were more cautious: “I fear the Canadian Parliament will demur to the terms, & it is difficult to see how they can carry out the Railway which is the principal inducement to the Columbians.”111

Two days later Musgrave wrote again, sending printed copies of the address to the Queen in duplicate, one “by the overland route via Olympia in Washington Territory,” but “as this mode of transmission is uncertain from the state of the Roads at this time of the year,” retaining the original to be sent “by the Mail Steamer next month direct to San Francisco.” As well, “Mr Trutch who was one of the Delegates sent to Canada last year for the purpose of negotiating arrangements for Union” was about to head to Ottawa “with a copy of this Document, by the Mail Steamer for San Francisco about the middle of February,” and would bring a copy with him.112 For all that British Columbia was about to change its status, communication with Britain, or for that matter the rest of the political entity it was about to join, was no more certain than it had been.

Musgrave’s task was done, as he wrote the same day, January 22, 1871, to Kimberley:

"This Colony has now finally accepted the terms offered by the Government of Canada for Union with the Dominion, and it only remains to carry out the details of the arrangement, which will probably be completed before the 1st of July next. After that is done my employment here will cease…But, I trust with some confidence in Your Lordship’s favorable consideration for further occupation elsewhere.113

"

Life goes on

In the interim, life went on in a British Columbia in the making much as before. Serving members Hankin, Phillippo, Hamley, and Pemberton, along with Edward Graham Alston, were in February 1871 appointed to the new Legislative Council.114 The same month Musgrave initiated the process of amending the colony’s constitution to permit “Responsible Government to come into operation at the first Session of the Legislature subsequently to the Union of the Colony with Canada.”115 Yet even as times were changing, a minute on the letter from Musgrave apologizing for “the irregularity and lateness” of the annual Blue Book acknowledged, a little regretfully perhaps, that “no more Blue Books will be received from B. Columbia as the Colony is about to be merged into the Dominion of Canada.”116

The observation was not quite accurate given a final Blue Book was dispatched in June 1871 for the year 1870, about which Musgrave noted cheerfully how “the Year was fairly prosperous in respect of the material interests of the Colony.”117 British Columbia’s final Blue Book described in upbeat fashion how “the explanation of the diminution of Import Duties is to be found…in the increased production of articles of food and general consumption within our own borders”; “Agriculture, Stockraising and the minor operations of Husbandry have been much and successfully extended both on the Mainland and on Vancouver Island”; and “applications for land for settlement have been numerous.” Gold mining was ongoing, and Vancouver Island coal deposits were further developed. The Blue Book not unexpectedly took special pleasure in noting how “the public debt will be assumed by Canada,” and work would soon be “commenced for the construction of the proposed Railway.”118 The future was in view.

British Columbia becoming Canadian

The work of unification was underway. Writing to Musgrave on May 27, 1871, Kimberley, as he signed himself, had “the honor to transmit from Her Majesty an Order in Council dated 16th May uniting British Columbia to the Dominion of Canada,” for which “I caused the 20th of July to be fixed for this Union.”119 Whether the letter was the usual format or related in particular to British Columbia, the next paragraph must have struck a chord:

"It gives me much satisfaction to express to you how fully sensible Her Majesty’s Government are of the energy zeal and ability with which you and the Officers of your government have laboured to effect this Union, which it is confidently anticipated will confer important and lasting benefits in British Columbia and by the consolidation of Her Majesty’s possessions in North America will greatly promote their progress in the career of prosperity of which they seem destined by their natural resources.120

"

Responding on July 12, 1871, Musgrave described how “I have given due publicity to the Order in Council, and have proclaimed the 20th of July to be observed as a Public Holiday in honor of the occasion.” He was optimistic about the future: “On that day this Province will quickly become a part of the Dominion, and so far as the future can be foreseen, there is now no reason to apprehend any reaction of public feeling adverse to the Union, or any difficulty in arrangement of the several Departments of public business.” Musgrave went on to detail with a sense of relief how, very importantly, “arrangements have been completed for payment of the floating Public Debt by the Canadian authorities through the Bank of British Columbia on the 15th instant,” and how long-time public figure Joseph Trutch, who had been appointed lieutenant governor, would be “on his way to Victoria at the end of this month,” allowing Musgrave to be on his way.121

As for the Colonial Office, it quite literally cleaned house in respect to its one-time colony, requesting the following of Musgrave in a June 28, 1871, letter:

"You will select from the Records of the Colony all Despatches from the Secretary of State to the Governor which are marked as confidential or secret, and also similar Despatches from the Governor to the Secretaries of State and cause them to be packed in packing cases and transmitted to me at this office. If it should be found that such Despatches have been bound up with public Despatches, I shall wish you to send them all to me. If on the other hand the public Despatches have been kept separately you will cause them to be packed in cases to await any directions…as to their ultimate disposal.122

"

In case that letter did not arrive, Kimberley alerted Musgrave in a letter of July 5, 1871, how: “I sent to you this day at 3.5 P.M. a telegraphic Despatch in the following words ‘Pack up and send home all Confidential and Secret Despatches.’”123 Just like that, in the blink of an eye, British Columbia was shorn of a critical aspect of its history as a colonial possession by a Colonial Office now shifting its attention to its myriad other British colonies around the world.

Musgrave on his way

As for the indispensable Musgrave, he had been preparing his exit for some time, energized by the need for surgery in London to repair a problem with his leg prior to his next appointment. In January 1871 he had alerted the Colonial Office, as it obviously already knew, that “the Governments of Ceylon and Hong Kong will both become vacant some time during this year by expiration of the usual term of service,” and he was hopeful.124 Musgrave departed British Columbia on July 25, 1871, for London, where he would “report in person the satisfactory completion of the Union of this Colony with Canada.”125 He would go on to important postings as governor of Natal (1872–73), South Australia (1873–77), Jamaica (1877–83), and Queensland (1885–88). As Musgrave had found out time and again, to be in British Columbia was to be alone and lonely, and it can only be hoped his next postings were more agreeable.

British Columbia saved for Canada

As explained in the annual Colonial Office List enumerating the “Colonial Dependencies of Great Britain,” British Columbia was by virtue of having been “admitted into Union with the Dominion of Canada on the 20th July 1871” no longer present as a colonial possession.126

British Columbia had been saved for Canada. The deed was done just a quarter of a century after Britain and the United States had in 1846 divided the almost wholly Indigenous Pacific Northwest between them. More so than with any other constituency, Indigenous women had been used and abused in the process, but, while victimized, had not faltered, descendants into the present day testifying along with their male Indigenous counterparts to their strength of character in the face of adversity. What would otherwise have been the case, it is impossible to know in retrospect, just as it is respecting other aspects of a British Columbia in the making.

There had not been perfection but there had been survival, and the newly minted province of British Columbia set in place in 1871 was now on its own to prove itself in a Canada that was itself in the making.127

1 As an example, Dr. Archibald Alexander Riddel of Toronto to Earl Carnarvon, under-secretary of state for the colonies, June 9, 1858, CO 305:9.

2 Douglas to Newcastle, Separate, April 15, 1862, CO 60:13.

3 Douglas to Newcastle, Separate, April 15, 1862, CO 60:13.

4 Murdoch to Rogers, permanent under-secretary for the colonies, May 20, 1862, May 20, 1862, CO 60:14.

5 Douglas to Newcastle, Separate, October 27, 1862, CO 60:13.

6 Douglas to Newcastle, Separate, October 27, 1862, CO 60:13.

7 A. Brown to Board of Trade, March 21, 1862, enclosed in Sir James Emerson Tennent to Rogers, May 21, 1862, CO 60:14.

8 Minute by ABd [Blackwood], May 23, 1862, on A. Brown to Board of Trade, enclosed in Tennent to Rogers, May 21, 1862, CO 60:14.

9 October 1, 1862, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861–62: 163, on typescript in Ecclesiastical Province of British Columbia, Archives.

10 November 8, 1862, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861–62: 174.

11 October 24, 1862, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861–62: 174–75.

12 Birch to Cardwell, No. 14, March 2, 1866, CO 60:24.

13 William Seward, speech at Chautauqua, March 31, 1846, in George E. Baker, ed., The Works of William Seward (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1884), vol. 5: 320, cited in David E. Shi, “Seward’s Attempt to Annex British Columbia, 1865–1869,” Pacific Historical Review 467, 2 (May 1978): 218.

14 Charles John Fedorak, “The United States Consul in Victoria and the Political Destiny of the Colony of British Columbia, 1862–1870,” BC Studies 79 (Autumn 1988): 7.

15 Fedorak, “The United States Consul in Victoria,” 13.

16 David Higgins, Daily British Colonist and Victoria Chronicle, September 12, 1866, p. 2, and Leonard McClure, Victoria Evening Telegraph, September 10, 1866, p. 2, both cited in Brent Holloway, “‘Without Conquest or Purchase’: The Annexation Movement in British Columbia, 1866–1871” (master’s thesis, University of Ottawa, 2016), 48 and 47.

17 On the meeting and its aftermath through 1871, see Holloway, “‘Without Conquest or Purchase’”; and Willard E. Ireland, “The Annexation Petition of 1869,” British Columbia Historical Quarterly 4, no. 4 (October 1940): 267–87; and Ireland, “Further Note on the Annexation Petition of 1869,” British Columbia Historical Quarterly 5, no. 1 (January 1941): 67–72.

18 For an accessible overview, see Daniel Heidt, ed., Reconsidering Confederation: Canada’s Founding Debates, 1865–1999 (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2018), which includes Patricia E. Roy, “‘The Interests of Confederation Demanded It’: British Columbia and Confederation,” 171–92.

19 Shi, “Seward’s Attempt to Annex British Columbia, 1865–1869,” 223–25; also John A. Munro, The Alaska Boundary Dispute (Toronto: Copp Clark, 1970); David Joseph Mitchell, “The American Purchase of Alaska and Canadian Expansion to the Pacific” (master’s thesis, Simon Fraser University, 1976), 59–68, for an excellent overview of contemporary perspectives on the course of events.

20 Hugh L. Keenleyside, “British Columbia—Annexation or Confederation?” Canadian Historical Association, Report of the Annual Meeting, 7, no. 1 (1928), 36.

21 February 7, 1861, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861: 15.

22 August 23, 1862, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861–62: 128.

23 May 14, 1862, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861–62: 47.

24 May 21, 1861, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861: 52.

25 February 3, 1862, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861–62: 14. The family was living at the time in Olympia, Washington.

26 Keenleyside, “British Columbia—Annexation or Confederation?” 37–38.

27 Dorothy Blakey Smith, ed., The Reminiscences of Doctor John Sebastian Helmcken (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1975), xxxciii.

28 Smith, Reminiscences of Doctor John Sebastian Helmcken, 247.

29 G.P.V. Akrigg and Helen B. Akrigg, British Columbia Chronicle 1847–1871: Gold and Colonists (Vancouver: Discovery Press, 1977), 340–41.

30 For a succinct summery, Keenleyside, “British Columbia—Annexation or Confederation?” 34–40 with the quotation from 39–40.

31 Seymour to Buckingham, Private, June 26, 1867, CO 60:28.

32 Seymour to Buckingham, No. 90, July 15, 1867, CO 60:28.

33 Minute by FR [Rogers], September 16, 1867, on Seymour to Buckingham, No. 90, July 15, 1867, CO 60:28.

34 Minute by CBA [Adderley], September 17, 1867, on Seymour to Buckingham, No. 90, July 15, 1867, CO 60:28.

35 Annexation Petition, July 1867, enclosed in Allan Francis to F.H. Seward, July 2, 1867, in Consular Letters from Victoria, Vancouver Island, vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Department of State Archives), cited in Ireland, “The Annexation Petition of 1869,” 268, fn. 4.

36 Smith, Reminiscences of Doctor John Sebastian Helmcken, 182–83.

37 Smith, Reminiscences of Doctor John Sebastian Helmcken, xxii.

38 Seymour to Buckingham, Separate, September 24, 1867, CO 60:29.

39 Seymour to Buckingham, Separate, September 24, 1867, CO 60:29.

40 Holloway, “‘Without Conquest or Purchase,’” 40.

41 Seymour to Buckingham, Secret, September 25, 1867.

42 Minute by FR [Rogers], November 6, 1867, on Seymour to Buckingham, Separate, September 24, 1867, CO 60:29.

43 Seymour to Buckingham, No. 162, December 13, 1867, CO 60:29.

44 Minute by WR [Robinson], December 18, 1867, on Seymour to Buckingham, No. 90, July 15, 1867, CO 60:28.

45 Seymour to Buckingham, No. 104, August 22, 1868, CO 60:33.

46 Peter O’Reilly, Magistrate, Yale District, to the Colonial Secretary, August 3, 1868, in Seymour to Buckingham, No. 104, August 22, 1868, CO 60:33.

47 O’Reilly to the Colonial Secretary, August 3, 1868, in Seymour to Buckingham, No. 104, August 22, 1868, CO 60:33.

48 O’Reilly to the Colonial Secretary, August 3, 1868, in Seymour to Buckingham, No. 104, August 22, 1868, CO 60:33.

49 E. Sanders, Magistrate, Lillooet District, to the Colonial Secretary, August 5, 1868, in Seymour to Buckingham, No. 104, August 22, 1868, CO 60:33.

50 Sanders to the Colonial Secretary, August 5, 1868, in Seymour to Buckingham, No. 104, August 22, 1868, CO 60:33.

51 H.M. Ball, Magistrate, New Westminster District, August 26, 1868, to D. Maunsell, private secretary to Seymour, in Seymour to Buckingham, No. 104, August 22, 1868, CO 60:33.

52 Ball, August 26, 1868, to Maunsell, in Seymour to Buckingham, No. 104, August 22, 1868, CO 60:33.

53 Ball, August 26, 1868, to Maunsell, in Seymour to Buckingham, No. 104, August 22, 1868, CO 60:33.

54 W.A.G. Young, colonial secretary, to Seymour, April 30, 1868, enclosed in Seymour to Buckingham, No. 45, May 14, 1868, CO 60:32; on a subsequent motion that was lost, Seymour to Buckingham, No. 74, July 28, 1868, CO 60:33.

55 Seymour to Buckingham, No. 125, November 30, 1868, CO 60:33.

56 Seymour to Buckingham, No. 125, November 30, 1868, CO 60:33.

57 Minute by FR [Rogers], January 19, 1869, on Seymour to Buckingham, No. 125, November 30, 1868, CO 60:33.

58 Minute by FR [Rogers] January 19, 1869, on Seymour to Buckingham, No. 125, November 30, 1868, CO 60:33.

59 Minute by FR [Rogers] January 19, 1869, on Seymour to Buckingham, No. 125, November 30, 1868, CO 60:33.

60 Seymour to Buckingham, No. 136, December 21, 1868, CO 60:33.

61 Noted in minute by CC [Charles Cox], February 2, 1869, on Seymour to Buckingham, No. 136, December 21, 1868, CO 60:33.

62 Seymour to Buckingham, telegram, January 20, 1869, CO 60:37.

63 Seymour to Granville, No. 27, February 23, 1869, CO 60:35.

64 “Resolution of Legislative Council of 17 February 1869,” enclosed in Frederick Seymour to Granville, No. 26, March 4, 1869, CO 60:35.

65 Seymour to Granville, No. 26, March 4, 1869, CO 60:35.

66 Seymour to Granville, No. 40, March 17, 1869, CO 60:35.

67 Granville to Seymour, Confidential, June 2, 1869, CO 398:5.

68 Hankin to Granville, No. 1, June 14, 1869, CO 60: telegram, June 15, 1865, CO 60:36.

69 Hankin to Granville, Confidential, July 19, 1869, CO 60:36.

70 Hankin to Granville, Confidential, July 19, 1869, CO 60:36.

71 Moody to Granville, June 17, 1869, CO 60:37, with minute by CC [Cox], June 18, 1869.

72 Granville to Hankin, No. 57, June 16, 1869, NAC RG7:G8C/16.

73 Kent M. Haworth, “Sir Anthony Musgrave,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/musgrave_anthony_11E.html.

74 Granville to Musgrave, No. 84, August 14, 1869, NAC RG7:G8C/16.

75 Granville to Musgrave, No. 84, August 14, 1869, NAC RG7:G8C/16.

76 Granville to Musgrave, No. 84, August 14, 1869, NAC RG7:G8C/16.

77 Musgrave to Granville, No. 7, September 3, 1869, CO 60:36; Granville to Musgrave, No. 105, December 4, 1869, CO, NAC RG7:G8C/16.

78 Musgrave to Granville, No. 1, August 25, 1869, CO 60: 36.

79 Musgrave to Granville, No. 9, October 15, 1869, CO 60:36.