Chapter 3: James Douglas and the Colonial Office (1859–64)

James Douglas had singlehandedly—or rather doublehandedly along with the Colonial Office in faraway London headed by Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton—managed the 1858 gold rush across the vast, then almost wholly Indigenous space that is today’s British Columbia. Events during the year that changed everything went relatively peacefully, and almost certainly led to Douglas being kept on as governor of the two distant British colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, even following Lytton’s departure in June 1859 after a change of government in Britain. Douglas stayed on even though it was evident that with the passage of time the Colonial Office was losing interest in the future province.1

It was not until the spring of 1864—a good dozen years since Douglas’s 1851 Colonial Office appointment to govern Vancouver Island, where he continued to make his home, and half a dozen years since also taking on the mainland colony of British Columbia in 1858—that Douglas was replaced by separate governors for the two colonies.

James Douglas’s governorship

That the Colonial Office, headed by the new secretary of state for the colonies, Henry Pelham Clinton, 5th Duke of Newcastle, kept James Douglas on as governor of the two distant colonies for as long as it did is to his credit. The mainland colony fell out of favour early on, or, more realistically, was never in favour compared to its island counterpart.

One of all governors’ responsibilities was to sum up annually the place they oversaw in a compilation of facts and numbers known as a Blue Book, owing to the colour of the books they were to use in a British practice going back a century and more. On reading Vancouver Island’s inaugural Blue Book in 1865, Douglas’s successor as governor, Arthur Kennedy, considered “substantially correct…the European, Negro, and Chinese together numbering about 8000 and the Aboriginal Indians about 10,000.”2

What James Douglas did not mention in his ongoing correspondence with the Colonial Office was that his governance was being buttressed by the presence of Bishop George Hills, who arrived from England in January 1860 as the appointed head in the two colonies of the Church of England, today’s Anglican Church. The two men socialized in everyday life due in part to their living in proximity to each other in Victoria. Hills’s private journal, which forms the basis of Chapter 5, makes clear his awareness of the ways in which Douglas, while an acquaintance, did not in his view quite measure up:

"The Governor is a self made man…He has not been to England for many years…Hence makes mistakes in dealing with those who repeat here English society. Yet he is anxious to do the right thing. He has been accustomed to be absolute in the Hudson’s B.C. & secret in his plans, & to deal with inferiors. His position is difficult when in contact with accomplished men of the world as our Naval & Military people & where a Legislature & Council are concerned. He is resolute in his own view.3

"

Douglas having charge did not, in Hills’s view, signify his being necessarily respected and admired.

Judge Begbie’s perspective

While Bishop Hills’s observations were for his eyes only and would continue to be so virtually into the present day, those of British Columbia’s chief justice Matthew Baillie Begbie, a Cambridge University graduate dispatched from Britain in 1858 who routinely travelled large areas of the mainland colony in order to hold court, were routinely shared with Douglas.4 Begbie made his first trip in the spring of 1859 accompanied by “Mr [Charles] Nicol the High Sheriff of British Columbia and by Mr [Arthur] Bushby the Registrar and assize clerk” and by “an Indian body servant, and 7 other Indians carrying our tent, blankets, and provisions.” Along the way Begbie noted the lay of the land, potential for agriculture, feasibility for grazing of animals, water and other natural resources, ease of communication, gold mining and access to foodstuffs. His descriptions were so comprehensive as to include on his inaugural trip “restaurants on the road, one at Spuzzum, one at the top of the hill immediately above Yale, one at Quayome [Boston Bar], and another about 18 miles from Lytton.” The “chief points” striking Begbie were:

- The ready submission of a foreign population to the declaration of the will of the executive, when expressed clearly and discreetly, however contrary to their wishes.

- The great preponderance of the California, or Californicized element of the population, and the paucity of British Subjects.

- The great riches, both auriferous [being rocks or minerals containing gold] and agricultural, of the country.

- The great want of some fixity of tenure for agricultural purposes.

- The absence of all means of communication except by foaming torrents in canoes or over goat tracks on foot, which renders all productions of the country except such as like gold can be carried with great care in small weight.5

Colonial Office uncertainty

The Colonial Office, for its part, continued to wax hot and cold—or more accurately warm and lukewarm—respecting a governor over whom it did not have the immediate control it would have possessed had he been immersed in its expectations prior to his appointment (as opposed to being an independent-minded outsider). Douglas was from time to time commended, as with a Colonial Office minute of 1860 by Assistant Under-Secretary Thomas Elliot, who noted that “his views seem to me broad and commanding, and to afford fresh evidence of that practical ability which I always think apparent in Mr Douglas!”6

Douglas’s complaints respecting the Royal Engineers, to which we shall soon turn, were not, however, to the Colonial Office’s liking.7 Looking ahead in time, Douglas’s replacements in 1864 would be handpicked for their acquiescence to the status quo, serving only a year, until the two colonies were joined into a single colony of British Columbia that would five years later, in 1871, be hustled into the new Dominion of Canada.

Minding the Fraser River gold rush

Prominent among Douglas’s obligations alongside his separate governance of the two colonies was minding British Columbia’s ongoing gold rush centred on the Fraser River. While some arrivals spent their first winter in Victoria, others headed south to California, and some few stayed put. Come January 1859, Douglas reported to Lytton how miners in his namesake community of Lytton had “generally suspended work in consequence of the coldness of the weather.”8

From Douglas’s perspective as an Englishman, it was taken for granted that miners were, with some exceptions, not equal to himself. Douglas was, and would continue to be, suspicious of non-Englishmen almost as a matter of course. Faced during the slack winter months of 1858–59 with a cluster of bored gold miners, he reduced them in his mind to “reckless desperadoes requiring the strong arm to curb them.” Douglas generalized to the Colonial Office as to how “we cannot rely on a force raised from the mining population.”9

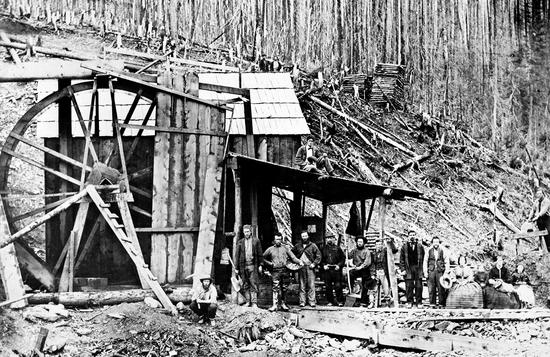

In Douglas’s reports on the gold rush’s second year he wrote, “The miners are full of confidence in the resources of the country, and look forward to great discoveries.” By evoking recently arrived Chinese men conveying soil in wheelbarrows to a nearby river for washing, a hundred mules weekly packing in foodstuffs for miners, Port Douglas’s “white population” of about 150 contributing three hundred dollars toward the construction of a needed bridge, and a detachment of Royal Engineers making a road from Hope to Boston Bar, Douglas sought to hold the attention and the confidence of the faraway Colonial Office.10

The dilemma posed by the Royal Engineers

Of all the issues that muddied Douglas’s governorship of the mainland colony of British Columbia, none would be more time-consuming than the Royal Engineers. Their presence was fundamental to the roadbuilding, which was necessary to cohere the far-flung colony, and at the same time frustrating since Douglas was not able to exercise the control he sought over them.

From the Colonial Office’s perspective, British Columbia was, despite its gold rushes, not unlike some sixty other British possessions around the world, each intended to become self-sustaining. Even when the Royal Engineers dispatched to British Columbia in the summer of 1858 were still in England, the secretary of state for the colonies, Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, assured Douglas, “They will relieve you of much anxiety,” given “they will immediately on their arrival, proceed to survey and lay out lands for sale and occupation,” hence covering their cost.11 What was not taken into account, Douglas pointed out, was that the 170-some men were outside his control, so he could not direct how they might best serve the colony of which he had charge.

Despite Lytton’s written instructions to their head, Colonel Richard Clement Moody, that the Royal Engineers “incur no unnecessary expenses,” and despite Moody’s awareness even before he left England that all items would be “chargeable eventually to the Colony,” Moody’s demands were seemingly endless. Not only did he insist that he and “two Servants” travel together to British Columbia “in a manner befitting…the position of honour and trust” accorded him; he also ordered to be taken with him from England two years of mainly food supplies, by one estimate totalling 250 to 300 tons.12 An increasingly exasperated Governor Douglas explained to the Colonial Office in July 1859:

"The Colony is most anxious to acquit herself of every obligation conferred upon her, and she is quite capable of meeting all her civil expenditures in a befitting and proper manner, but the cost of the maintenance of the Military Force, with the heavy charge for [the men’s] Colonial Pay, is at present more than her Finances can bear…

I cannot refrain from remarking, however, that the expense of sending the Royal Engineers to British Columbia, is a charge that can scarcely with perfect justness be assigned to the Colony, seeing that after all the object in view was one purely of an Imperial character.13

"

It is indicative of Douglas’s skill at delineating the young colony’s position that the two Colonial Office minutes on the letter’s arrival in London at the end of August 1859 understood the situation and sided with Douglas, if to no avail. As described by recently promoted junior clerk Henry Turner Irving, “it was originally intended by Sir E. Lytton that those expenses should be, at any rate for a time borne by this Country” and only “afterwards in consequence of the favorable (but as they have proved over estimated) accounts of the probable revenue of the Colony, it was decided that the cost [apart from the men’s regimental pay], should be paid from the Colonial revenue.”14 The rules of the game had changed without Douglas’s foreknowledge or agreement.

The second minute, from the more senior Herman Merivale, who had studied law at Oxford University and taught there prior to joining the Colonial Office, was blunt and providential respecting the Royal Engineers’ consequences for British Columbia’s economy and possibly also for the colony’s future given American proximity:

"It is perfectly clear that the Colony cannot pay for the military force, & that any attempt to make it do so can only end in disastrous debt. The question lies between the “kind & lenient” policy advocated by the Governor, and that of withdrawing almost all the military force & leaving the Colony to take care of itself…

There is no doubt this latter policy requires firmness & nerve to follow, &, above all, that it cannot be pursued unless we are determined to disregard the apprehensions arising from the American character of the population. Probably the experiment might be safely risked. But it is not to be forgotten, that this corner of the world is becoming a very important point with a view to foreign affairs. Indian hostilities & other causes have established in Oregon a large detachment (relatively speaking) of the small American army.15

"

The uncertainty occasioned by the Royal Engineers was compounded by the self-importance of its head, who was also appointed “Commander of Lands and Works,” which came with an additional salary and status, or so Moody considered. As early as August 1858, almost certainly fed by Moody, rumours flew, as they would do until his departure from British Columbia five years later, that “Col. Moody has been appointed Govr of the new Colony of British Columbia.”16 The claims may have originated in his also being named lieutenant governor in what, Lytton explained to Douglas, was a “dormant” position whose “functions in that capacity will commence only in the event of the death or absence of the Governor.”17 Moody’s wife, a British banker’s daughter with, like her husband, a strong sense of self, anticipated—as indicated by her private correspondence and by their being quartered in what was named “Government House,” where Douglas also stayed when in the colony’s capital of New Westminster—that her husband would soon accede to the governorship, their large family thereby becoming “luxuriously comfortable.”18 The Moodys viewed his position as a stepping stone to greater things as opposed to an end in itself.

Moody’s view of himself was not shared by others. Pointed minutes began to appear in the Colonial Office’s internal correspondence even before the Royal Engineers left England and would continue throughout Moody’s years in British Columbia:

"I so entirely mistrust Colonel Moody—who is always in a hurry & frequently wrong. ABd19

There is no end to the wants of R. Engineers. ABd20

With regard to provisions,…I have never yet heard it surmised that we are to feed either the functionaries or the population of British Columbia from England. TFE21

Captn Moody’s requisition is of reckless magnitude. TFE22

"

A little over a year later from within the Emigration Office, also in London:

"The Engineers appear to have done very little useful work [building roads] in B. Columbia, and to have devoted themselves mainly to military duties, & laying out capital cities. Might it not be useful to address the Govr [Douglas] on this subject, if the Engineers are continued? I am much inclined however to think that they wd. be better away as a military [underlining in original] body—only a sufficient number being retained to direct the labour of others in roadmaking & surveying.23

"

And two years later from a long-time Colonial Office employee:

"If anything went wrong it was entirely owing to Colonial Moody’s personal share who is the worst man of business I ever encountered.24

"

The impasse between Douglas and Moody widened due to the latter’s repeated demands for additional funds which the mainland colony did not have the means to provide, and so were passed on to the Colonial Office to be added to British Columbia’s growing debt to be repaid at some future date.25 Moody seems to have made at best a middling attempt to accommodate the colony’s priorities, so Douglas regretfully informed the Colonial Office in March 1859: “Moody is of opinion that they will be able to do little more than to attend to the Survey of Town Lots, and that the rural Surveys, the construction of Roads and Bridges, and opening of the great communications of the country must be otherwise provided for.”26

A thoughtful internal minute of March 1859 respecting British Columbia’s finances, by the twenty-seven-year-old Earl of Carnarvon—then under-secretary for the colonies, who would eight years later in 1867, as secretary of state, secure passage of the British North America Act, bringing the Dominion of Canada into being—indicates the considerable extent to which Lytton’s increasingly hard line was not shared across the Colonial Office.

"Sir Edward Lytton

Though you have expressed a strong opinion upon Colonial expenses in B. Columbia…I must trouble you with a somewhat different view of the case…It is hopeless to expect that during the first year of its existence a sufficient revenue can be raised to defray the necessary expenses of establishing a government and organising a civilized community. No Colony can be created under the circumstances of B. Columbia without some sacrifice: & if it is not the sacrifice of law and order, as was the case in California, it must be a sacrifice of money. Hitherto we have been remarkably fortunate in B. Columbia, but the good fortune is owing to the remarkable ability & firmness of Govr Douglas & to the presence of a certain amount of military force…To say that we will supply him with men but that he must pay for them amounts in fact to a refusal.27

"

Lytton’s April 1, 1859, response to Carnarvon makes clear that Douglas’s one-time ally was no more. The glow was gone, and Lytton had moved on in his priorities. His condescending minute signalled Douglas’s easy disposal should need be:

"No doubt in all Gold Colonies, violence will ensue. So there also in public schools—if a boy gets a black eye is he to send home for his Nurse. If at a gold Digging, there is a row are the Colonists to send home to the Mother Country for police? If so the boy will never be a man nor the Colonists worthy to be free men…If this Colony is to be a Colony of Men it must protect itself & pay for that protection by a local Tax…The first duty of a Colony pretending to be English is to fund its own police…That before he undertakes to pay for them, he will pay the Colonial Charges of Col. Moody…If he cannot do it I will get a Governor who can & who will.28

"

Lytton’s minute signalled the full extent to which colonies such as British Columbia and Vancouver Island were below “the Mother Country” in status, their governors dispensable.

It was not only the Engineers themselves who had to be accommodated at British Columbia’s cost. Dispatched from England at the time the 150-some men came, or subsequently, were men’s wives or women to whom men were betrothed, and children, half the cost of whose voyages was to be “repayed by stoppages on the men’s pay,” the other half added to British Columbia’s debt.29

Men’s families lived respectably in housing provided for them at Sapperton near present-day New Westminster, but that was not sufficient.30 Moody routinely demanded additional services at British Columbia’s cost, including a separate hospital and the salary of a teacher for the growing numbers of children.31 By the beginning of 1863 there were “about 120 children who increase at the yearly rate of 25.”32 A laudatory article written from within the community on the centennial of the Engineers’ arrival evokes what appears to have been in effect seasonal employment in its description of how “the detachment gathered each winter, from November until March, in its camp at Sapperton, and their camp was then the centre of the social life and activity of the community,” their theatre “the scene of all kinds of dances and parties and balls.”33

Commending what the Royal Engineers did accomplish

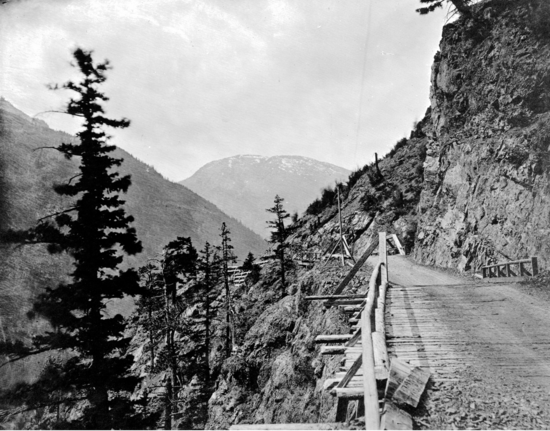

For all of the tension ensuing, virtually from the first contact between James Douglas as governor and Richard Moody as head of the Royal Engineers, Douglas did his best to commend what they accomplished.34 He applauded to the Colonial Office in June 1859 how “a body of Royal Engineers” along with “civilian labourers…improving the Harrison River Road into a good wagon Road…will open a safe, easy, and comparatively inexpensive route into the interior of British Columbia and give facilities at present unknown to the miner and merchant, for the development of its material resources.” A road from Fort Hope to Lytton was also in process, owing, Douglas added, not to the Royal Engineers, but rather to local inhabitants having “with great spirit immediately raised the sum of Two Thousand Dollars ($2000) among themselves for the purpose of opening a horse-path,” whereupon two Engineers were dispatched, but only to assess its quality.35

A month later Douglas again drew the Colonial Office’s attention to the Royal Engineers’ contributions to roadbuilding:

"The opening of roads through the mountainous districts of British Columbia into the interior, is now the object which has the strongest claim upon our attention. A party of Royal Engineers are now employed in making the road from Fort Hope to Boston Bar, and a detachment of Royal Engineers and Royal Marines [stationed on a ship then surveying the maritime portion of the boundary established in 1846 between Britain and the United States], exceeding one hundred (100) men are employed in widening and improving the Harrison Lillooet Road.

The transport by that road is already very great. About one hundred (100) pack mules leave Douglas [named after the governor, with a population of 150 whites] weekly with freight for Bridge River.

"

Based on returns made up at Douglas, 3,600 tons of provisions were carried over the road from its opening in November 1858 through the first half of 1859.36

Roadbuilding’s complexities

Opening up the large interior topped Douglas’s agenda for the mainland colony. Realizing roadbuilding’s complexities, Douglas shared with the Duke of Newcastle, secretary of state for the colonies, in February 1860 his long-held reservations respecting the Royal Engineers being the means for achieving that goal:

"I was directed by the Despatches of Sir Edward Lytton, Nos 30 and 31 of the 16th of October 1858, to rely entirely upon Colonel Moody and the Royal Engineers under his Command, for the great work of opening the communications of the Country. Experience has proved that the Force in question is utterly unable to grapple with the great difficulties with which it has had to contend, or to make any perceptible impression upon the rugged mountain passes which lead into the interior. Knowing therefore that if I relied upon the Royal Engineers the day would be far distant when this much desired end could be attained, I have felt it imperative on me not to delay longer in the employment of civil labour, and failing assistance from Her Majesty’s Government, I have resorted to the expedient of levying a Tax of £1 Sterling upon all pack animals leaving Douglas and Yale, in order to raise the funds necessary for the Expenditure required.37

"

Douglas’s initiative was applauded within the Colonial Office. Assistant Under-Secretary Thomas Elliot and Parliamentary Under-Secretary Chichester Fortescue noted in joint minutes of April 21 and 23, 1860, “the uselessness of the Sappers and Miners in B. Columbia.” A day later Newcastle noted how “if the Sappers & Miners could be replaced by an equivalent but less expensive force it would be well to do so.”38

Managing the two colonies

So as to keep watch on roadbuilding and to oversee British Columbia generally, Douglas regularly visited the mainland colony. He described Queen Victoria’s birthday in New Westminster on May 24, 1860, with a clear sense of relief at how “never I believe has any part of Her Majesty’s dominions resounded to more hearty acclamations of loyalty and attachment, than were had on that occasion,…a fact which I record with pleasure as a proof of the growing attachment of the alien population of the Colony to our Sovereign, and to the institutions of our Country.”39

Come autumn 1860 Douglas travelled “the newly-formed Waggon Road, then nearly finished as far as the lesser Lillooet Lake, 28 Miles from Douglas,” which he termed “a work of magnitude, and of the utmost public utility…laid out and executed by Captain Grant and a Detachment of Royal Engineers under his command, with a degree of care and professional ability reflecting the highest credit of that active and indefatigable Officer.” To Douglas’s pleasure respecting his namesake community, “a number of Waggons, imported by the enterprising merchants of Douglas, have commenced running on the new Road; and the cost of transport has already been greatly reduced.”40 By the time Bishop Hills visited the next May, Douglas had acquired as temporary, possibly permanent, residents “Italians, Germans, Norwegians, French, Africans,” along with “Americans, Scotch, English, & Irish—Canadians were also seen.”41

Douglas also “fell upon the new Road from Hope, which is carried over an elevation of 4000 feet without a single gradient exceeding one foot in twelve, a fact very creditable to Sergeant McCall and the detachment of Royal Engineers employed in marking out the line.” Respecting a “Horse-way from Yale to Spuzzum,” Douglas explained to the Colonial Office how “the arduous part of this undertaking—excavating the mountain near Yale—was executed entirely by a Detachment of Royal Engineers under Sergeant Major George Cann, and it has been completed in a manner highly creditable to themselves, and to the officers who directed the operation.”42 The next spring Douglas enthused how “Captain Grant with a detachment of 80 Royal Engineers under his command, and about 80 Civilian labourers” were roadbuilding from Hope “towards Shimilkomeen [Similkameen].”43

In their personal lives, the engineers followed a variety of pathways. Cann and Grant had arrived with their wives, while McCall came on his own. Cann also had a daughter, and Grant fathered three daughters in the future British Columbia. McCall soon arranged for his wife and four young children to join him from England, on which condition he committed to remaining in British Columbia. While Cann and Grant purchased land out of their wages, when the time came to decide, both families returned to England.44

Enter the Cariboo gold rush

Even as the Fraser River gold rush continued to demand Douglas’s attention, a wholly separate rush sprang to life. It became a matter of not only managing what was, but also dealing with a huge, almost wholly Indigenous, chunk of British Columbia accessible only with difficulty. Reporting to the Colonial Office in the spring of 1861, Douglas fretted over “men whose excited imaginations indulge in extravagant visions of wealth and fortune to be realized in remoter diggings.”45 He was by then daily receiving “the most extraordinary accounts” respecting the region known as the Cariboo,46 which was “distant some 500 miles” from New Westminster.47 There was in consequence, Douglas explained to the Colonial Office, a fundamental shift in the geography of gold mining, itself just three years old in British Columbia:

"The Mining Districts of Thompson’s River, and of the Fraser below Pavillion, have been almost abandoned by the white Miners of the Colony, who have been generally carried away by the prevailing excitement of the Cariboo and Antler Creek Mines…About 1500 men are supposed to be congregated in those Mines, and the number is continually augmented by the arrival of fresh bodies of Miners.48

"

For those making it to the Cariboo, work processes were very different than with the earlier finds. Rather than men panning for gold near the surface on their own or in small groups, the Cariboo was, in Douglas’s words, “what may be styled the Company era where individual Miners must club together, and the possession of a certain amount of Capital is requisite for sinking Shafts, running drifts, rigging drafts, rigging pumps, bringing in water, before Gold can be obtained.”49 The expense and practical difficulties meant that while men dreaming of a better future nibbled at the edges, profiting from the Cariboo rush was complex, expensive, and seasonal due to the inclement winter weather, with many of those reaping the profits returning to their distant homes as opposed to settling down to the two colonies’ benefit.50

Travelling the mainland colony in the summer of 1861 to hold court, Judge Begbie not unexpectedly stressed the need for roadbuilding:

"It is of course impossible that any roads or trails can be pushed in such a country so as to keep even within sight of the eager swarms who scattered themselves in every direction in search of gold. But the Caribou [spelling in original] may now probably be deemed an ascertained auriferous district of considerable extent and very attractive richness; and trails will be required next year for the passage of 5000 or 6000 men at the least—and their provisions, during 5 months of the year.51

"

Uncertainty over the mainland colony

Whereas the longer-settled Vancouver Island held few surprises as a British colony, its mainland counterpart was a different matter. In addition to ongoing attention to gold miners was financial uncertainty arising from the cost of the Royal Engineers.52 Had not a gold rush to the distant Cariboo ensued just as its predecessor was losing its lustre, it is impossible to know, but intriguing to ponder, the fate of the mainland colony, or for that matter of both colonies.

It was also the case that, even as events on the mainland played themselves out, the United States lurked just next door, both to the south and to the north, and might well have pounced to retrieve territory many Americans felt should have been theirs in the 1846 boundary settlement. Indicative of the ongoing tension was a January 1861 suggestion by the British Foreign Office to the Colonial Office consequent on British Marines being dispatched to San Juan Island, then in dispute between the two countries:

"A Battalion might be usefully stationed in Vancouver’s Island, where, and in the adjoining Colony of British Columbia, we have large interests at stake, while, on the other hand, the neighbouring provinces of the United States abound in a squatter population only too ready to create disturbance, but against which, if directed towards the British provinces, such a force might exercise a very salutatory check.53

"

The roads so critical to making the mainland colony accessible had as a complement, Douglas pointed out in July 1859, the Colonial Office’s goal of making land accessible. “The regular settlement of the country by a class of industrious cultivators is an object of the utmost importance to the Colony, which is at present dependent for every necessary of life, even to the food of the people on importation from abroad.” Although “Colonel Moody is making great efforts to bring surveying parties rapidly into the field,…no country land has as yet been brought into market,” for which “there is much popular clamour.”54

The Colonial Office was in consequence not best pleased, as indicated by Henry Irving’s minute on Douglas’s letter: “The delay in bringing the country lands into the market is a serious evil…It is probable too that the R. Engineers are not very rapid surveyors.”55

Newcastle’s minute respecting landholding was both critical and providential: “I believe we must resort to the American fashion. The very neighbourhood to U.S. territory renders it next to impossible to maintain the present system.”56 The reference was to pre-emption, whereby in the United States land could be marked out, registered, and taken up prior to surveying and payment. Adopted on the mainland in 1860 as a temporary measure, except in New Westminster where land continued to be, following the earlier practice, sold at auction, pre-emption remained in place until entry into Confederation in 1871.57

In August 1859 Douglas forwarded a report from Moody respecting landholding which, on the way to Newcastle’s desk, was minuted by the experienced Arthur Blackwood:

"I know not to what it is owing, but this is the first report from an Engineer Officer on the interior of the Country which we have recd. And this only refers to a Section up the Harrison River. The Engineers were sent out to explore, survey, lay out lands, make roads & Bridges. They have been for nine months in the Colony, & with the exception of laying out some Lots of land at Langley, & New Westminster, (and making a very few miles of road) this is all the produce of their Labors.58

"

While taking no action, the secretary of state for the colonies, the Duke of Newcastle, responded crisply in a follow-up minute how “I have for some time thought that the labours of the Engineers make very little show!”59 Caught in the middle, Douglas continued to update the Colonial Office as best he could, commending the Royal Engineers for what they did accomplish, even as the colony racked up a growing debt on their behalf.

The Colonial Office rethinking the Royal Engineers

What Douglas may not have realized was that it was at this point the Colonial Office began to rethink the Royal Engineers’ presence in British Columbia, commissioning an internal report which concluded that “the amount of work done is insignificant.”60 Responses from within the Colonial Office reinforced its conclusions. Chichester Fortescue, parliamentary under-secretary for the colonies, got to the point of the matter:

"I have no doubt that they are an extravagant failure…They have done nothing in the way of laying out country lands [intended to pay for their keep] & very little in the way of road making…I feel myself no doubt that the best thing that could be done would be to recall Col. Moody & the Sappers…& giving all the option of taking their discharge in the Colony & receiving grants of land.61

"

The Duke of Newcastle’s minute validated Douglas’s long-held concerns respecting the cost of the Royal Engineers, acknowledging that British Columbia was effectively funding Britain’s foreign policy, to the detriment of colonial revenues:

"I have no doubt that the Engineers in B. Columbia are a “Mistake” and I was meditating their withdrawal when the S: Juan affair broke out. This affair renders a [underlining in original] Military force Necessary & I should not feel justified in withdrawing the Engineers without the substitution of another force which I admit might easily be both better and cheaper…I greatly deprecate this heavy expense for little practical result.62

"

Newcastle’s reference was to the ongoing dispute over San Juan and neighbouring islands which straddled the forty-ninth parallel between British and American possessions, where an American military force had landed in July 1859. In 1872 an international arbitrator would award the San Juan Islands to the United States.

Funding roads

As Douglas discovered, the Colonial Office commending and funding roadbuilding were two very different matters. His frustration with the slow course of events caused him in a letter of August 28, 1860, to propose a more direct approach. Douglas used as the impetus for doing so the cross-border consequences of “great discoveries of Gold in the Shilmilcommen [Similkameen], and on the Southern frontier of British Columbia near Colvile [Washington]”:

"Prodigious efforts have hitherto been made by the people of Oregon to throw supplies, by means of the Columbia River, into the Southern frontier of the British Possessions, and since these new discoveries are so close to their own Territory, these efforts have been redoubled, and unless we adapt instant and effective measures, the revenues of the Colony will suffer to an extent which we can hardly now foresee.

"

Because the funds needed to construct the necessary roads were far beyond “the means of payment in the Colony,” the “only resource” for “the youngest of Her Majesty’s Colonies” was, in this unexpected circumstance, Douglas explained to the Colonial Office as persuasively as he could in a letter of August 28, 1860, to “turn to the Mother Country to endeavor to effect a Loan to the extent of Fifty thousand pounds” at a rate “paid by other British Colonies of the same Continent.”63

On the letter’s arrival in London in early October, seasoned employee Arthur Blackwood, with over a third of a century of Colonial Office experience, acted on his own initiative to determine whether such a loan was feasible. As to the reason he did so:

"It would be the making of B. Columbia to have a sum of money to spend in the construction of roads, or even paths capable of conveying provisions & merchandize into the inaccessible interior of the Country in return for the gold, the produce of the Miners’ labour. But money cannot be obtained on the spot. The Governor hence appeals to the S. of State to help him to effect a loan here. He wants £50,000…The Colony with no other security to offer than tracts of wild land, at present almost worthless, I had misgivings as to the possibility of the Crown getting the money it wants on any terms in London; but happening to meet an eminent Banker and acquaintance of my own, I endeavored to ascertain from him whether it was at all likely that the loan cd be effected.64

"

Having reviewed the relevant documents, the banker acquaintance informed Blackwood on October 23, 1860, that a loan was feasible at 6 per cent interest on bonds payable in twenty years with “the revenue and Crown property of British Columbia” as “an efficient security.”65

In what was a trenchant critique of Douglas from within the Colonial Office, Blackwood added in his minute of October 24 that, if possible and agreed by the Colonial Office, “the distribution of the money should be settled by the Governor in concert with some of the principal officials in B. Columbia,” not “to deprecate the honor and integrity of Governor Douglas,” but to prevent “a whisper raised…in a Colony where he is perfectly despotic in power.”66 The parliamentary under-secretary, Oxford University graduate Chichester Fortescue, added on October 27 that if the proposal went ahead, “a Council of some kind sh. be associated with the Govr, the reasons for which wd. be increased by the fact of his having a Loan to expend on Road-making.”67 Douglas needed minding.

Three months later the resourceful James Douglas prepared a letter summarizing for the Colonial Office British Columbia’s 1860 revenue and expenses. Its two principal sources of income were duties on imports totalling £35,519 and land sales of £10,962, with total expenditures excluding the cost of the Royal Engineers totalling £44,124.68 Within this frame of reference, Douglas audaciously proposed nine roadbuilding projects for 1861 totalling 358 miles:

| Cart Road | Pemberton to Cayoosh [Lillooet] | 36 miles |

| Same | Hope to Similkameen | 74 miles |

| Horse road | Boston Bar to Lillooet | 30 miles |

| Same | Lytton to Alexandria | 150 miles |

| Same | Cayoosh to Lytton junction | 30 miles |

| Road in progress | New Westminster to Langley | 15 miles |

| Same | New Westminster to Burrard Inlet | 9 miles |

| Same | US boundary to Semiahmoo Bay | 14 miles |

| Same | Spuzzum to Boston Bar | 20 miles69 |

Douglas was well aware that by writing as he did, he was challenging the boundaries of his authority and had for that reason made explicit the proposed roads’ locations, distances, and financing.

Douglas’s letter generated favourable responses. A minute by Thomas Elliot on March 30, 1861, seconded by Chichester Fortescue on April 3 and by Newcastle on April 7, read: “This is on the whole, a satisfactory account of the progress of Revenue in B. Columbia. Probably it will be acknowledged, with an intimation to that effect.”70 After more back-and-forth, the Treasury approved on February 27, 1862, Douglas’s “raising of any sum not exceeding £100,000 on the security of the Revenue of British Columbia.”71

Not so fast.

Assessing British Columbia’s finances

In the meantime, back charges owed by British Columbia to the Treasury were brought to the attention of the Colonial Office. In a letter to Douglas of February 22, 1862, Newcastle pointed out that British Columbia already owed £26,958.9s10d. Also owing was £6,900 for silver coins sent out from London to British Columbia in 1860 at a time when none were available in the colony, for which Douglas had promised repayment but not done so.72

Thomas Elliot’s astute minute of February 27, 1862, on the Treasury’s letter respecting British Columbia’s debt pointed out how the silver coins’ repayment would, “as the Treasury themselves point out with some satisfaction, reduce the Colony to bankruptcy,” and, “with all respect, I cannot but think this more petulant than statesmanlike.”73 Chichester Fortescue’s minute may have impacted Douglas’s future as governor: “Whatever we may think of the tone & temper of the Try [Treasury], they have disclosed to us conduct on the part of the Govr most insubordinate and unfair to the Sec. of State [for the Colonies].”74

The complexities of British Columbia’s finances originating with the Royal Engineers did not end there. The Treasury followed up with the Colonial Office respecting the £100,000 loan Douglas requested for roadbuilding “to be raised on the security of the Colonial Revenue of British Columbia.” The Treasury was doubtful, given that it was already bearing half the colonial expenses of the Royal Engineers, as opposed to their being wholly absorbed by British Columbia. In consequence “they are of opinion that the Governor should be informed that any immediate proceedings for raising the Loan must be suspended.”75

Assistant Under-Secretary Thomas Elliot’s minute of March 24, 1862, on the Treasury’s letter was by contrast sympathetic to Douglas on the grounds that in his letters “the Governor made out a striking case for the necessity of Roads, and of borrowing money for their construction.” Elliot reminded the others how “in most new Settlements, as well as in a large proportion of all the British Colonies, the entire Military expenditure is defrayed by the Mother Country, British Columbia will not be doing less in this respect, but more, than most other Colonies.”76 To push home the case, Elliot in his very long minute pointed out, along with the time that had elapsed since Douglas made his request, the reality of American proximity combined with British Columbia’s physical isolation:

"So far back as in a despatch from hence of the 1st of March 1861, the Governor was told that his plan was viewed very favorably, provided that he could supply certain information. This information he has supplied, and believes it (on grounds which seem to me reasonable) to be sufficient.

The value of time must be considered. More than a year and a half has elapsed since the Governor wrote his despatch of August 1860 which convinced the Secretary of State—and indeed the Treasury itself—of the necessity of a speedy provision for the construction of roads but the Treasury wanted further information, and now that it has come, they call for more.

At this rate there will be no end of correspondence with a place which is one of the most inaccessible of British Possessions. Nor is real help to be expected from the Governor; in the past he has furnished his information; the future must be judged of by the light of experience and on general considerations which ought to be at least as well understood at home as by the Governor of British Columbia.

Whilst we are writing, American speculators are acting; and it would be a serious responsibility if by mistrust and a craving for more certainty than is attainable in human affairs, the Home Authorities should find that the progress of the Colony was crippled, and possibly foreign channels opened for its supplies.77

"

Douglas’s plan as supported by Elliot was not, however, the Colonial Office’s plan. Writing on May 13, 1862, Newcastle summarily informed Douglas that henceforth one half of the Royal Engineers’ annual pay of £22,000 “must be defrayed by Colonial Revenue.” He went on to remind Douglas of previous “heavy over drafts made by you” to pay bills incurred by the Royal Engineers, which was from Newcastle’s perspective “to appropriate British money to the use of the Colony without leave.” Newcastle did, however, conclude his admonitions with a consolation prize of sorts:

"I am well aware that the proposed repayments relating to the cost of the Royal Engineers will seriously impair your current means for the important object of the construction of roads, which is in itself so material to the prosperity of the Colony. I have however conveyed to the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury my strong recommendation that you should be authorized to make a fresh law providing for the creation of a loan for this purpose, limited to the extent of £50,000.78

"

Douglas’s request for £50,000 had, it appears, come full circle.

Tallying up the cost of the Royal Engineers

The Royal Engineers’ demands, which Douglas had no authority to refuse, ate away at British Columbia’s finances.79 In August 1862 he responded at length to the Colonial Office in respect to claims of overspending:

"I earnestly hope that it may be within my power to shew that the sums which I am charged with having improperly drawn have been expended solely on account of the Royal Engineers, under the immediate control and superintendence of their Commanding Officer, Colonel Moody, and that the particular sum of £10,704, occurring under the head, Roads, Bridges, and Surveys, is for the most part, if not wholly made up of items of expenditure peculiar to the Royal Engineers, and of no benefit to the Colony…

I have kept the public works going by various expedients of short loans, and that I hope to continue to do so, and with your Grace’s kind co-operation to bring the Colony satisfactorily out of her present financial embarrassment.80

"

The next spring, April 1863, Douglas again reminded the Colonial Office of “the heavy expenses incurred by this Detachment—expenses that I cannot but think are not proportionate to its strength, and are certainly not proportionate to the circumstances of the colony.” Excluding Moody’s “£1200 Civil Salary as Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works” paid him in England, in 1862 “the expenditure of The Royal Engineers within the Colony amounts to the sum of $22,325,” of which £10,500 was offset by the Imperial Treasury, leaving “a balance provided by the Colony of nearly £12,000” that somehow had to be got.81

The same month Douglas provided the Colonial Office with an accounting of what British Columbia got in exchange. “From a Return which I have just received from Colonel Moody, I find that the value of the works performed by the Royal Engineers during 1862 may be estimated at about £3,500.” To this amount Douglas added £1,500 for miscellaneous services for a total of £5,000, which left “a sum of £7,000 actually paid out of the Revenue of the Colony, for which no appreciable return is received.” Adding to that the £10,500 funded by the Imperial Treasury and Moody’s “£1200 Civil Salary,” £23,525 was expended in 1862 on the Royal Engineers for £5,000 worth of services.82

Douglas shared with the Colonial Office his lengthy search to secure an accurate accounting of Royal Engineers’ expenses:

"I have long intended to represent to your Grace the heavy expenses incurred by this Detachment—expenses that I cannot but think are not proportionate to its strength, and are certainly not proportionate to the circumstances of the Colony—and I desired to accompany my representation with certain statistical information which I could only obtain from Returns to be furnished by Colonel Moody.

I have called upon Colonel Moody for these Returns but from the delay that has taken place in procuring them in the shape I wished, and from a positive refusal being made in one case, I regret that I cannot testify to Colonel Moody’s cheerful co-operation in this matter. With respect to the case of refusal, as a very serious point is involved I beg herewith to enclose Colonel Moody’s letter upon the subject: for I feel that it is scarcely just that the Colony should be compelled to bear so heavy a burden, without having the least control in the matter of expenditure.

Colonel Moody declines to comply with my request upon the ground that it would be an infringement of Military Rule. It is remote from my desire to trespass in any way upon Colonel Moody’s province so far as his Military duties are concerned, and I have always made it a point most carefully to abstain from doing so; but as it seems to me that the request I made, which was simply to be furnished with a nominal List of all persons rationed at the public expense, has more of a financial than a Military bearing, I cannot accept as satisfactory Colonel Moody’s explanation for declining to render the required Return. My reason for asking for it was this: I was anxious to place before your Grace, the numbers and qualities of the different persons rationed, more especially the women and children, the wives and families of officers and men; but as several attempts to obtain the numbers properly classified, failed, I, to avoid further correspondence and delay sought to obtain a nominal list of the persons rationed, from which, the information I required, could have readily and satisfactorily been gathered.

The expenditure of the Detachment during 1862 has exceeded the expenditure in 1861 by £2271. The increase is mainly found under the head of Rations—the Provisions in 1861 costing £6020 in 1862 £7805 a difference of £1784. At present I do not exactly know how to account for this large increase, but a proportion of it is no doubt attributable to the greater number of persons rationed—the number of children in the Detachment having been more than trebled since it left England, and the number is increasing every day. I believe the number of women and children rationed at present exceeds 150 and as this is beyond the strength of the whole detachment I believe it is out of all proportion to what is authorized by the regulations of the Army.

Under these circumstances I do not hesitate to beg that your Grace will authorize me to reduce the establishment by granting a discharge to those who may have large families and to those who may wish to settle in the Colony; I believe many so circumstanced would readily avail themselves of the offer, and in the cases of invariable good conduct the grants of land referred to in Sir Edward Lytton’s Despatch No 14 of 2nd September 1858 might be made, by which means the cost of the Detachment could be considerably reduced.83

"

Moody, in the letter Douglas enclosed, written nine months earlier on August 1, 1862, had waxed indignant “that for an Officer com[mandin]g in a Colony to be called on to supply, even to a Governor, a Nominal [underlining in original] Roll of Troops is so far out of all Military Rule that I trust your Excellency will not press it.”84

The Royal Engineers’ departure

By the time Douglas’s long and detailed letter reached the Colonial Office in June 1863 it had already been decided to withdraw the Royal Engineers. Arthur Blackwood noted how “this report strengthens the propriety of the measure resolved upon by the Duke of Newcastle of withdrawing the R. Engineers from B. Columbia,” with their “shipping” already arranged.85 In a joint minute, Thomas Elliot, Chichester Fortescue, and Newcastle were grateful to Douglas for supporting the decision:

"This despatch contains proof of the great costliness of the Engineers and affords evidence of their having rendered a very disproportionate amount of service to the Colony. It seems to me to show that they are likely to have been so much spoilt as to render it questionable whether we should endeavour to retain any of them for a further period.86

"

Two months earlier Assistant Under-Secretary Thomas Elliot reflected in another context on what might be the Royal Engineers’—and more particularly Moody’s—epitaph:

"I do not think that the officers of the Royal Engineers employed in B. Columbia have done themselves credit. They have shown much too great a disposition to employ their time in agitation, and in attempts to show that they could manage matters better than the Governor, than which nothing could be more remote than the truth.87

"

The departure of the Royal Engineers from British Columbia in the summer of 1863 seemed like an afterthought.88 One hundred of the 165 men, many of whom had already received financial assistance in bringing wives and children to British Columbia, opted to remain. Those doing so were eligible to take up “grants of agricultural land, not exceeding thirty acres…on condition of residence and Military Service in the Colony if called upon,” but as of October 1865 only one had done so.89

Many of the Royal Engineers settled on their own resources near where they had been based in New Westminster, variously contributing to their new home as constables, surveyors, craftsmen, and merchants, with descendants commendably doing so into the present day.90 Left behind as a souvenir of sorts was “a quantity of stores,” being the remains of the two tons of mainly food supplies Moody had demanded be taken with the Royal Engineers to the faraway colony. No one in the Colonial Office knew quite what to do with them and wondered if “Colonel Moody might be able to advise as to the best mode of proceeding.”91 What ensued has been lost from view.

Moody and his family were among those returning to England. They did so despite his having acquired during their time in British Columbia over three thousand acres of land on which he had created what British Columbia’s most eminent historian Margaret Ormsby terms “his model farm.”92 What might have spurred Moody to do so was his perceived claim, made even before leaving England, that he was Douglas’s successor in line with his secondary position as chief commissioner of lands and works and his dormant position as lieutenant governor. Newcastle minuted on a letter respecting Moody at the time the Engineers left British Columbia in April 1863, “There is no doubt he is looking to the Governorship, (for which he is not fit) and would be a discontented Subordinate to Mr Douglas’ successor.”93

Indicative of Moody’s legacy as viewed at the time, Colonial Office staff were alerted to “be careful not to employ any terms which will give Coll Moody an oppy of offering to stay in B.C. in the capacity of Ch. Commr.”94 The immediate reason for doing so was, as spelled out in two minutes, “the recent eposé [underlining in original] by Governor Douglas of the fact that the whole of the numerous wives and families of these Engineers were drawing rations, at an immense cost to the public, whilst the Governor could not obtain so much as even a list of the recipients, and whilst the whole value of the labor performed by the Royal Engineers for the Colony in 1862 was £3,500 [underlining in original].”95 An unsigned sidebar on the minute penned from within the Colonial Office reads “43 women 29 children.” Moody had, from the perspective of the Colonial Office, finally gone too far. But he did exact a petty revenge, vetoing Douglas’s proposed appointment of a successor as commissioner of lands and works from within the ranks of the Engineers who had served under Moody in British Columbia.96

Describing himself in the 1871 British census as a “retired Major General of the Royal Engineers with full pay,” Moody, along with his wife and by then eleven children aged from two to seventeen years (of whom the three between ages eight and eleven had been born in British Columbia), were living at Caynham House in the small village of Caynham in Shropshire, England.97

Change in the making in British Columbia

Douglas’s letter of October 27, 1862, describing his seasonal trip through the British Columbia interior gives a sense, as it was intended to do, of the state of “these most indispensable public works in British Columbia” on the eve of the Royal Engineers’ departure.98 “I cannot speak too favourably of the newly formed Roads. In smoothness and solidity they surpass expectation.”99

Indicative of Douglas’s predisposition against gold miners as such, he found “a striking improvement in all the principal towns, except Hope, which is almost deserted in consequence of the migration of the inhabitants to Carribou [spelling in original] and other places; an evil to which gold producing countries, occupied by a purely mining population, are peculiarly exposed.” Changes of which Douglas approved continued to be linked to his long-lived hope for arrivals from Britain so as to realize the British Columbia of his dreams and aspirations:

"I noticed Settlers are beginning to take up Public Land along the course of the Public Roads, and are turning their attention to tillage and Stock raising. A few successful experiments showing how profitable farming may be made in British Columbia will induce other persons to follow their example; and I apprehend the majority of British emigrants will probably find agricultural pursuits better adapted than mining, to their tastes and former habit of life.100

"

What Douglas, or for that matter the Colonial Office, may not have realized was that settlers were arriving, quietly and independently, of their own accord. In May 1861 at Saanich, a few miles north of Victoria, Bishop Hills encountered at an “evening camp meeting,” a Protestant social event, “a party of settlers with cattle, wagons & horses on their way to find a settlement.” As described by Hills in his journal, the arrivals were James Douglas’s ideal settlers: “They were Englishmen, lately arrived from Oregon preferring the old English farmer to the Stars & Stripes. They have been some years in the States, one of them was from Gloucestershire, another from Wales.” Hills summed them up as “wayfarers in the wilderness,” and it is intriguing to wonder where they ended up and how they fared.101

Douglas also reported in his October 27, 1862, letter on overland communication with Canada, describing how some of those arriving by a different route than his road in the making “suffered a good deal of privation” along the way. Douglas’s commitment to linking British Columbia eastward across the Rocky Mountains is evident in his hopeful suggestion that

"Should Her Majesty’s Government deem it a matter of national importance to open a regular overland communication with Canada, I submit that parties of workmen might be dispatched from this Colony at less expense than from Canada to carry their views [of an overland route] into effect.102

"

Douglas’s unrelenting roadbuilding

In his follow-up letter of December 4, 1862, Douglas once again directed the Colonial Office’s attention to roadbuilding “as soon as the ground thaws in Spring,” in this case to “be continued to Alexandria, from whence Fraser’s River is navigable to the very bases of the Rocky Mountains,” for which “I shall be pressed for funds…and shall be under the necessity of again appealing to Your Grace for assistance.”103 Blackwood’s minute on the letter observed a bit wearily how “Governor Douglas threatens us with further appeals for money for his road in B. Columbia,” a second by Newcastle how “I suppose he means more loans,” which is indeed what he meant.104

Douglas wrote again a week and a half later, December 15, 1862, regarding “the precise position in which I am placed with respect to these most indispensable public works in British Columbia.”105 Douglas’s long description exemplifies his untethered commitment to roadbuilding even in the difficult terrain that still today characterizes parts of British Columbia. A critical section had been contracted to Joseph Trutch, a recently arrived English surveyor and engineer who would become a strong supporter of entry into Confederation and the new province’s first lieutenant governor.106

In his very long letter of December 15, Douglas pointed out the great difference that the completion of roads made to the colony’s development and to residents’ well-being:

"Up to the end of last summer the lowest charge for carrying from Douglas by way of Lillooet to Alexandria was 61 cents per pound, or £1366 per Ton! Now in anticipation of the completion of the road, one of the most substantial Carriers in the Colony has lately tendered for the transport of all Government stores required in 1863 over the same line, at the rate of 21 Cents per pound: that is at a reduction of no less than 40 cents per pound or 896 dollars per ton, as compared with the rate charged in 1862, being in short a saving to the public to that extent upon all goods carried from Douglas to Alexandria, merely from the effect of forming Roads.

"

Douglas concluded with the plea which underlay his writing in such detail: “I trust I have said sufficient to convince Your Grace of the Propriety of my being permitted to extend the British Columbia Loan to £100.000.”107

Funding roadbuilding

Douglas’s plea worked. The three minutes on his December 15, 1862, letter—one by Thomas Frederick Elliot, who had been for the past decade and a half assistant under-secretary, another by parliamentary under-secretary Chichester Fortescue, and the third by the letter’s recipient, the Duke of Newcastle—could not have been more complimentary of the hard work that had gone into roadbuilding and more immediately into the letter.

"Having raised £50,000, Governor Douglas asks leave to extend his loan to £100,000 for the important object of increasing the means of communication in the Colony. The question is, may this be recommended to the Treasury? TFE108

To me the Governor’s appeal seems irresistible, and the object upon wh. the money is to be spent—Road-making—one for which a young Colony may fairly borrow. There is probably no country in the world where Roadmaking is so vital, & likely to be so reproductive, as B. Columbia. CF109

I entirely agree. Moreover an early [underlining in original] permission to raise the loan is almost as important as the loan itself. Will Mr Fortescue endeavour to get Mr Peel to attend to this as soon as the letter goes to the Treasury. N110

"

Newcastle’s March 12, 1863, response was in the spirit of the three minutes. Respecting Douglas’s request “to extend the Loan for the construction of roads in British Columbia to £100,000,…the grounds alleged by you appear to Her Majesty’s Government sufficient…for raising a further sum of £50,000 by loan upon the security of the general revenue of the Colony.”111

Douglas replied a month later on May 14 that the necessary law “similar to the British Columbia Loan Act of 1862” had been passed, meaning the task Douglas had set for himself as governor to open up British Columbia was on its way to completion:

"By the completion of this road, the two great thoroughfares of the country will be established. From the Coast to Douglas, and from the Coast to Yale, the Fraser is navigable. From these two points roads are carried to Alexandria, by which a vast district which has no water communication is rendered accessible. From Alexandria to the Rocky Mountains even, the Fraser is again navigable, and private enterprise has already launched a Steamer on the Fraser at Alexandria. These great road works being accomplished, the Government has faithfully done its duty to the Country, and the development of its valuable resources may safely be left to the energy & enterprise of the people governed by wise and wholesome laws.112

"

And so Douglas got more of his road, which was at the very heart of his governance of British Columbia. In consequence, as of September 14, 1863:

"The whole journey from New Westminster to Alexandria may now be readily made in eight days by a connected line of Steamboats and stages running constantly between these places. From Soda Creek below Alexandria, a river Steamer plies on Fraser River to Quesnel and a good horse road, formed this season, connects the latter place with Richfield, sixty three miles (63 miles) distant, thus completing the chain of communication between the Coast and the centre of the Carriboo District. These works have been necessarily expensive, but they are of incalculable advantage to the Colony.

"

The consequences were wide-ranging, among them “the charge for packing has very materially decreased, prior to that period, it averaged 25 to 30 cents per lb but now it has fallen to 12 and 15 cts.”113

In the aftermath of success, Douglas acknowledged to the Duke of Newcastle how he considered “the work of opening roads—the very essence of the existence of the Colony—and what an anxious and uphill task I have had in endeavouring to compass a work of so much magnitude and importance.”114

The changing positions of British Columbia and Vancouver Island

The Colonial Office’s approval of roadbuilding was almost certainly due, at least in part, to changing perceptions of the Cariboo gold rush and thereby of the mainland colony more generally. The influential London newspaper The Times had tracked the British Columbia gold rush as it leapt from the faraway colony’s southern edge into its vast interior, where James Douglas’s roads headed. The arrival of Douglas’s letter of request on March 14, 1863, followed a flurry of articles published over the previous couple of months highlighting the Cariboo rush, British Columbia as a whole, and the feasibility of overland travel from the Cariboo to Canada.115

Vancouver Island was a different matter, Douglas explained to the Colonial Office a couple of months later:

"The total white population does not exceed eight thousand (8000) souls; about two thirds of these are engaged in trade and mechanical pursuits; the remaining third are agricultural Settlers, and day labourers working for wages. The agricultural classes are, with few exceptions, persons of small means and not possessed of much enterprise or intelligence. Their operations are of the most limited kind, and chiefly effected by their own labour.116

"

If Vancouver Island lost out, British Columbia was the beneficiary of the changing times in more ways than gold mining:

"Continual accessions are being made to the general population of the upper Country, the newly formed roads having given a prodigious impulse to settlement, by opening up valuable farming Districts which before were virtually closed to men of moderate means by difficulties of access, and the enormous cost of transport, and impenetrable at any cost for all kinds of Machinery except such as could be taken asunder, and packed through the mountains on Mules.117

"

Douglas reported to the Colonial Office that Gold Commissioner Peter O’Reilly had similarly observed, on his way from Lillooet to the Cariboo in the spring of 1863, “large tracts of land that were fenced in, and at all the way side Houses great preparations for embarking largely in farming operations; and moreover in the District between Bridge Creek and Williams Lake he states that 500 acres of land were actually under crops of various kinds.”118

By late spring and summer 1863, Douglas took pleasure in reporting how, in the mainland colony, “the immigration of this year so far consists of about four thousand five hundred persons (4,500 persons), chiefly able bodied men, exclusive of women and children, a class of which this Colony is still lamentably deficient,” with “about 2000 persons” passing through Yale “on their way to the Upper Country,” and another two thousand otherwise arriving.119 Come November Douglas anticipated that “a considerable number of people will remain here during the winter—it is generally said about 1000,” while others “are now retreating in great numbers from Carribou [sic] and other remote Districts of the Colony on account of the apprehended severity of winter.”120 Douglas was optimistic that “Carribou and other Districts of British Columbia will surpass in the extent and richness of their auriferous deposits, every other Gold Country in the world,” not surprising given “the annual produce of Gold in the Carriibou District is estimated at One Million sterling.”121

Repeated requests for more equitable governance

Alongside the challenges posed by the Royal Engineers and road construction was everyday governance. Douglas had, from the time he took charge of Vancouver Island in 1851 and of British Columbia in 1858, been subject to complaints respecting a ruling style perceived by those not directly benefiting from it as authoritarian. From the perspective of British Columbia residents, Douglas’s governorship advantaged Vancouver Island at the expense of the newer colony. Following a meeting held in the mainland capital of New Westminster on May 22, 1860, signatories of a memorial denounced Douglas in personal terms for “His Excellency not being an English Statesman,” and called for “a Representative Government.”122 The memorial, which in Douglas’s words “purports to be signed by the British Residents in the Colony of British Columbia,” had 413 signatures from across British Columbia, one of them being crossed out as “not a British subject,” with another 200 names added later.123 This was at a time when the colony’s White population was about three thousand people.

Douglas’s defence for having diverted British Columbia’s governance from the pattern of Vancouver Island, where a House of Assembly had been established in 1856 at a time when, according to the Colonial Office, “the population cannot have exceeded 500 persons of all ages and sexes,” was that while he had “established Municipal Bodies at New Westminster, Hope and Yale,…for a Representative Government the country is not yet sufficiently settled; and the British element in the population is still so small.”124 Blackwood agreed:

"It cannot be said that, with the exception of a very few Officers of the Engineers, & a sprinkling of other persons of the same standing in society, there is any settled respectable class of people in B.C. from whom you could create two creditable Houses of Parliament.”125

"

Chichester Fortescue, who also sided with Douglas, took note of the paucity of women and children among the “fixed population”:

"It seems to me quite too soon to introduce an elective [underlining in original] House of Assembly or Council into B.C. The number of Whites [underlining in original] in the Colony in July 1860, was estimated by Judge Begbie at 3000, of wh. probably not one half is a fixed population—with scarcely any women or children—and, doubtless, almost all of the class of labouring men, while but few are British subjects.126

"

Assumptions respecting demands for a resident governor and representative government appear to have been largely shared between Douglas and the Colonial Office.

Another memorial followed in the spring of 1861 consequent on, in Douglas’s dismissive words, “a series of political meetings” by eight “delegates” from Hope, Douglas, and New Westminster, whose “total populations of British origin, and from the Colonies in North America,” Douglas reminded the Colonial Office, were just 108, 33, and 164 “male adults.” He had the document put aside owing not only to the small numbers, but also on the grounds that “a majority of the reflective and working classes would, for many reasons, infinitely prefer the Government of the Queen, as now established, to the rule of a party” not representing them but rather only themselves.127 Douglas’s reasoning to the Colonial Office took for granted the superiority of British descent, hence the character of non-Indigenous British Columbia as of the spring of 1861:

"Without pretending to question the talent and experience of the petitioners, or their capacity for legislation and self-government, I am decidedly of opinion that there is not as yet a sufficient basis of population or property in the Colony to constitute a sound system of representative government. The British element is small; and there is absolutely neither a manufacturing nor farming class; there are no landed proprietors except holders of building-lots in towns; no producers except miners; and the general population is essentially migratory: the only fixed population, apart from New Westminster, being the Traders, settled in several inland towns from which the Miners obtain their supplies. It would I conceive, be unwise to commit the work of legislation to persons so situated, having nothing at stake, and no real vested interest in the Colony…a power not representing large bodies of landed proprietors, nor of responsible settlers having their homes, their property, their sympathies and their dearest interests irrevocably identified with the Country.128

"

Elliot’s minute on Douglas’s report on the spring 1861 meeting seconded Douglas’s reasoning that “the introduction of a representative Assembly in British Columbia would be premature and that the establishment of party Government would be not only premature but pernicious.” In sum:

"The Governor’s despatch appears to me very able, and calculated to inspire confidence in his judgment and in his intentions. The public has always seemed to me fortunate in obtaining at this remote and inaccessible settlement, so far out of the reach of much control from home, a Governor of so much self-reliance and practical ability.129

"

Another memorial urging “representative institutions” followed from nine petitioners who came together in the fall of 1861 at Hope in what they termed “The British Columbia Convention,” seeking a resident governor and officials, a public hospital, direct mail service, public schools, and other amenities. Douglas described them, or rather dismissed them, to the Colonial Office as sincere “quiet well meaning tradesmen.” In sending the memorial on to the Colonial Office, Douglas agreed in principle, but in practice was once again unable to act, he considered, due to the lack of a suitable British population, so he explained at length:

"With respect to the prayer of the Memorialists, that is, the redress of grievances, and the grant of representative institutions, I will observe that I fully, and cordially admit the proposition that liberty is the Englishman’s birthright, and that the desire for representative institutions is common to all Her Majesty’s subjects…Parliament has, however, seen fit, for good and sufficient reasons, to establish a temporary form of Government in British Columbia not unusual in the infancy of British Colonies, the Government of the Queen in Council, and Parliament, I think, adopted a wise and judicious course.

For my own part, I would not assume the responsibility of recommending any immediate change in the form of Government, as now established, until there is a permanent British population to form the basis of a representative Government, a population attached to the British throne and constitution, and capable of appreciating the civil and religious liberty derived from that constitution; blessings which I venture to assert are now enjoyed in the fullest sense of the term, by the people of British Columbia.130

"

The Colonial Office appears to have once again supported Douglas’s position. Elliot’s December 1861 minute put the issue in perspective in the larger context of the unquestioned social and racist assumptions of the time:

"I have little doubt that the postponement of Representative Government is in fact a benefit to this or to any other young Community…A large proportion of gold-diggers in the population, including a considerable admixture of Americans, would not add to the favorable prospects of popular Government. The time of course will come when this like every other British Colony situated in a temperate climate & occupied by inhabitants of European race, ought to possess a Representative Legislature.131

"

Another petition, drawn up a little over a year later “by a Clique in New Westr numbering 8 or 10 persons, shopkeepers &c,” mainly “Canadian emigrants,” sought “a resident Governor.” The writer lamented how “the preference has always been from the first artificially [underlining in original] given to Victoria [underlining in original] to the material prejudice of New Westr—in all points where the interests of the two came in collision.”132 The Colonial Office’s assistant under-secretary, Thomas Elliot, had a somewhat different perspective, minuting on a letter from Douglas arriving not long after:

"The representation which I have always heard on behalf of Vancouver Island is to the following effect, that the miners when they return from the diggings weary of their wild life and eager to exchange it for the pleasures and attractions of a civilized Town, will not remain at New Westminster which holds out no attractions, but hurry on to Victoria…they will not remain at an uninviting and inferior place on the river.133

"

At least for the time being, British Columbia’s governance under Douglas’s charge went on much as before. Writing to Douglas in June 1863 Newcastle considered that “the fixed population of British Columbia is not yet large enough to form a sufficient and sound basis of Representation, while the migratory element far exceeds the fixed, and the Indian far out numbers both together.” The secretary of state for the colonies was opposed to extending “a large amount of political power to immigrant, or rather transient Foreigners, who have no permanent interest in the prosperity of the Colony,” or to “foreign gold diggers” who were by definition “migratory and unsettled,”134 much less to Indigenous people who mattered not at all.

The many functions of roadbuilding

Douglas’s other emphasis, be it in the Cariboo or generally, lay in opening up to non-Indigenous settlement the sprawling British colony four times the size of Britain itself. In his September 1861 letter to the Duke of Newcastle, which lauded the Cariboo, Douglas had taken special pleasure in reporting that “the great commercial thoroughfares leading into the interior of the country from Hope, Yale and Douglas, are in rapid progress, and now exercise a most beneficial effect on the internal commerce of the Colony.”135