Chapter 1: Today’s British Columbia Coming into View

The origins of British Columbia as an Indigenous place go back to time immemorial. Its location on the western edge of a continent, North America, and an ocean away from the adjacent continent of Asia, long protected the region’s inhabitants from protracted non-Indigenous incursions, permitting them to develop distinct and complex ways of life best suited to their diverse physical settings.

Among the earliest non-Indigenous intruders into the future British Columbia was the Hudson’s Bay Company, a private fur-trading company based in London and operating in North America out of Montreal. The HBC’s search for beaver pelts, valued in Europe for trimming garments, was legitimized by the British government, which in 1670 granted it a trading monopoly over the entirety of the vast region known as Rupert’s Land, defined as everywhere watered by rivers flowing from the Rocky Mountains into Hudson Bay.1 On December 5, 1821, the British government granted the HBC another exclusive trading licence, this one extending from the Rocky Mountains west to the Pacific Ocean. This grant was renewed in 1838 for another twenty-one years.

It was at about the same point in time that the HBC expanded into what was to become British Columbia.2 The Company hired both officers in charge and fixed-term employees on individual contracts that provided round-trip transportation from their place of recruitment and back again, with an agreed wage paid on returning there. In practice, numerous HBC employees opted, on their contract’s expiration, to remain where they had been last employed, due very possibly to their having along the way settled down with an Indigenous woman by whom they had a family—many with descendants into the present day.3

Dividing the Pacific Northwest

The fur trade was not the only factor shaping the course of events in the Pacific Northwest—the area lying between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific Ocean, and extending from today’s Alaska south through the American state of Oregon. While almost wholly fought elsewhere, the War of 1812 between Britain and the young United States also had an impact, with the two countries agreeing in its aftermath to joint possession of the Pacific Northwest.

This arrangement broke down in the 1840s due to westward migration from the eastern states. An expanding United States wanted it all, Britain resisted, and the result was a compromise. By the terms of a treaty signed on June 15, 1846, the two countries divided between them the vast, still almost wholly Indigenous Pacific Northwest along the forty-ninth parallel of latitude, with a jog south around the tip of Vancouver Island. The United States acquired the southern half to become the American states of Washington and Oregon and parts of neighbouring states, Britain the northern half to become the Canadian province of British Columbia.

Enter the Colonial Office

Britain’s new acquisition was, as a matter of course, turned over for administration to the Colonial Office in London, which minded territory around the world that Britain deemed expedient to colonize for its own economic and political purposes. The Colonial Office was a complex bureaucracy whose employees vetted incoming letters, both from those having charge of British possessions and from others with an interest in them. At the end of each letter he had read, the employee doing so would add a note, known as a “minute,” assessing its content to guide the response to the letter by the secretary of state for the colonies, who had overall charge of the Colonial Office and thereby of Britain’s colonial policy.

By the time of the 1846 boundary settlement, the Hudson’s Bay Company had for a quarter of a century operated a profitable fur trade across today’s Pacific Northwest, with half of its trading posts now in American territory.4 In anticipation of the 1846 agreement, the HBC had established a post on Vancouver Island, and in 1849 moved its Pacific Northwest headquarters from today’s American state of Oregon north to Vancouver Island. Not unexpectedly, in the settlement’s aftermath the HBC sought to acquire trading rights not just to Vancouver Island, but also to the entirety of newly acquired British territory north of the forty-ninth parallel.

Just three months after the signing of the June 1846 boundary agreement, the London governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, Sir John Henry Pelly, queried the British secretary of state for the colonies, Earl Grey, about “the intentions of Her Majesty’s Government as to the acquisition of lands, or formation of Settlements, to the North of Lat. 49.” Pelly reminded the secretary that “the Company, by a grant from the Crown, dated May 13, 1838, have the exclusive right of trading with the natives of the Countries west of the Rocky Mountains for 21 years from that date,” or to 1859.5 As Grey minuted on the end of this letter from Pelly, it seemed that unless the British government acted promptly to “consider what is to be done as to colonize the territory,” it might well slide into the HBC’s hands.6

Six weeks later, in October 1846, Pelly proposed to the Colonial Office, almost as a matter of course, that the HBC acquire “in perpetuity” Britain’s newly acquired territory:

"If Her Majesty be graciously pleased to grant the Company in perpetuity, any portion of the territory westward of the Rocky Mountains, now under the dominion of the British Crown, such grant will be perfectly valid [given] the Company may legally hold any portion of the territories belonging to the Crown, westward of the Rocky Mountains.7

"

Following up in March 1847, Pelly was even more straightforward respecting the HBC’s acquiring “the Queen’s Dominions westward of the Rocky Mountains in North America” so as to permanently extend its reach across what was, by then, Canada:

"I beg leave to say that if Her Majesty’s Ministers should be of opinion that the Territory in question would be more conveniently governed and colonized (as far as may be practicable) through the Hudson’s Bay Company, the Company are willing to undertake it, and will be ready to receive a Grant of all the Territories belonging to the Crown which are situated to the North and West of Rupert’s Land.8

"

The Colonial Office was, to its credit, incensed by how “without a word of preliminary discussion” the HBC had sent not only the letter, but also “the dft of a Charter to accomplish this object.”9 Written in traditional language and script echoing the original 1670 parchment charter granting Rupert’s Land to the HBC, the draft charter addressed to “Her Majesty Queen Victoria” detailed the history of “The Governor & Company of Adventurers of England heading into Hudson’s Bay,” before requesting, almost as a given, this additional “Grant of Territory in North America.”10

Vancouver Island becoming a British colony

While the British government rejected out of hand the HBC’s colonization proposal for the entirety of present-day British Columbia, stating it was “too extensive for Her Majesty’s Government to entertain,” a year later, in March 1848, Secretary of State for the Colonies Earl Grey invited the HBC governor Sir John Pelly to submit a scheme “more limited and definite in its object…for the Colonization of Vancouver’s Island.”11 The consequence was a ten-year HBC grant or lease.

To ensure Britain’s hold over Vancouver Island, on January 13, 1849, the island was declared a British colony overseen by the Colonial Office, becoming one more of an array of comparable entities around the world. Indicative of these British colonies’ multiplicity and uniformity during this period are the responses of officials in the Colonial Office to an 1864 request from the governor of Vancouver Island for information on fees charged by the colony’s attorney general. The officials compared fees charged for a similar purpose in New Zealand, Sierra Leone, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Hong Kong, Mauritius, four colonies in today’s Australia, and six colonies in the West Indies, as well as Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland.12

James Douglas in charge

The Hudson’s Bay Company had centred itself around its Fort Victoria trading post, founded in 1843 on the southern tip of Vancouver Island, which meant that no other location was considered for the capital of the new British colony.

The selection of a colonial governor to take charge should have been equally obvious.

Not so fast.

Rather than turning to experienced HBC officer James Douglas, who had overseen the construction of Fort Victoria and on whose behalf Governor Pelly lobbied, the Colonial Office in July 1849 offered the governorship of the colony of Vancouver Island to Cambridge University–educated Richard Blanshard.13 Dallying along the way, Blanshard did not arrive until March 1850, and was said to be “rather startled by the wild aspect of the country,” so that not unexpectedly, as summed up by historian James Hendrickson, his “tenure was both brief and unhappy.”14 Indicative of Blanshard’s outlook was his reporting to the Colonial Office four months after finally making it to Vancouver Island that “nothing of importance has since occurred in the colony, no settlers or immigrants have arrived nor have any land sales been effected.”15

Blanshard’s replacement on May 16, 1851, by the HBC’s choice of James Douglas was not unexpected. As one Colonial Office official minuted to the others on an arriving letter, “It will be regarded as a complete surrender to the Company,” to which came the response, “I fear this is true,” and from a third only: “I will submit Mr Douglas’ name to the Queen.”16

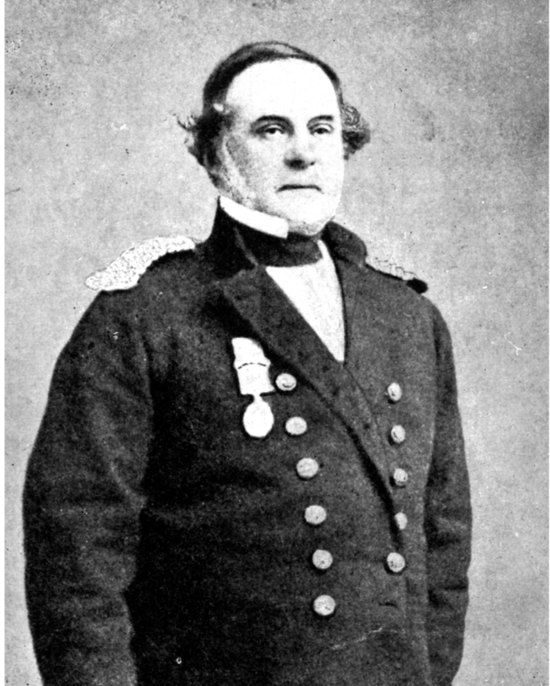

Born in 1803 in British Guiana to a Scots merchant and a local “creole” woman—meaning she had some Black ancestry—James Douglas was early on sent to a private boys’ school in Scotland and likely studied with a French tutor prior to being apprenticed at age sixteen into the fur trade.17 Douglas’s Black heritage would shadow him to the present day. Even in 2003, a book about “the dark-skinned, dour Douglas” opened with a chapter cheekily entitled “Idylls of a Mulatto King.”18 Posted in 1826 to Fort St. James in today’s central British Columbia, then known as New Caledonia, Douglas partnered with Amelia Connolly, the daughter of the post’s chief trader and of a Cree woman, and brought her with him to Fort Victoria, along with their children.

Following the 1846 boundary settlement, Fort Victoria—including nearby Esquimalt with, in Douglas’s words, its “magnificent harbor” making it accessible to seagoing vessels—took on a new role.19 As well as being the HBC’s headquarters of its ongoing trade west of the Rocky Mountains, Fort Victoria became the preferred site for retiring HBC officers and employees from across the Pacific Northwest.

The good news is that, as historians Adele Perry and John Adams describe in their fine biographies, James Douglas understood power, and while as governor he sought to protect the interests of the HBC, he did so within the larger British colonial framework in which Vancouver Island was enmeshed.20 Earlier, when Douglas had been stationed at other posts in the Pacific Northwest, he had arranged a boundary with the Russian American Company then in charge of today’s Alaska, traded with Mexican authorities in control of California, and checked out trading possibilities with the Hawaiian Islands, then a monarchy. He was a skilled negotiator comfortable in new situations.

The length of time it took for letters to travel from London to the west coast of North America, and for their responses to return to London, put the onus on James Douglas in the everyday and also in relation to the unexpected. The Colonial Office’s letter of May 19, 1851, informing Douglas of his appointment as governor, did not reach him in Vancouver Island’s capital of Victoria until October 3, with his letter of acceptance arriving in London on February 4, 1852.21 It was nonetheless the case that every letter received, whatever its origin, was given individual consideration by several officials when it arrived at the Colonial Office in London, each of them minuting on it his response. Nothing much slipped by them.

Colonizing Vancouver Island

James Douglas’s task as governor was to attend to Vancouver Island as a British colonial possession under Hudson’s Bay Company oversight. He was the Colonial Office’s conduit to this far corner of the world, about which no one knew more than he did. His detailed reports were intended to placate the Colonial Office as much as to effect change.

As acknowledged by Sir John Pelly early on, “one of the main objects of the Company is to civilize the native tribes by fixing settlers among them, who will find employment for them, and shew them the advantages to be derived from cultivating the Soil.”22 Douglas repeatedly emphasized the positive, as in a letter of 1852 evoking Indigenous peoples’ “many large and well kept fields of potatoes…and fine cucumbers.”23 Rather than non-Indigenous people taking Indigenous land by force, Douglas negotiated fourteen separate land purchases on Vancouver Island in the form of treaties between 1850 and 1854.

It was white folk, or rather the lack of them, who were the problem. The ongoing concern, in line with Colonial Office priorities, was “what the H.B.Cy intended to do about Colonizing the Island.”24 In fact, colonization was hampered by the HBC having agreed in January 1849 to the Colonial Office’s proviso that “no grant of land shall contain less than twenty acres,” and that it must be acquired at a cost of “one [English] pound per acre.”25

Given that the terms of colonization also required the introduction of suitably British settlers, it is unsurprising that nothing much happened. Dispatched to assess “the Colonization of the Southern part of Vancouver [Island],” visiting British admiral Fairfax Moresby observed in the summer of 1851 how, for all of Douglas’s “energy & intelligence,…the attempt to Colonize Vancouver [Island] by a Company with exclusive rights of Trade is incompatible with the free & liberal reception of an Emigrant Community.” The few settlers with whom Fairfax Moresby conversed were dissatisfied. “There is a general complaint that no Title deeds are granted, that the price of Land & the condition of bringing out Labourers, render the formation of a Colony hopeless.”26 It was, one Colonial Office employee minuted respecting the admiral’s report, “a very unsatisfactory state of affairs.”27 As calculated by historian Stephen Royle, 343 men, 119 women, and 179 children—a total of 641 persons—travelled to Vancouver Island on HBC vessels between 1848 and 1854.28

Proximity to the United States was from early on a mitigating factor, as it would continue to be. Anglican schoolmaster and chaplain Robert John Staines, who arrived in Victoria with his wife in 1849 to take up his dual position, was incensed when he learned that potential settlers, “by just crossing the straits & stating before a magistrate their intention to become Citizens of the U.S.,…will become entitled to 160 acres of land gratis & if they marry, to 320 any time they choose to settle.” By comparison, settlers in Victoria were faced with “land at £1 an acre, tied down as it is by conditions, which do not allow a man more than 20 acres except he import English labourers at the rate of 1 man for every 20 acres.”29

Writing a year later, in July 1853, Douglas was similarly focused on complaints from the handful of settlers over the price of land.30 What Douglas did not mention was that he was himself buying up land. By 1858, according to historian Margaret Ormsby, his holdings had grown from 400-plus acres in 1853 to 1,200 acres.31

Turning to the mainland

It was not only the Colonial Office that Douglas had to manage. The Hudson’s Bay Company brought with it to Vancouver Island its exclusive licence to trade for animal pelts with Indigenous people everywhere west of the Rocky Mountains, which had been agreed by the British government in 1821 and renewed in 1838 for twenty-one years.32 This gave the HBC charge not only of Vancouver Island but also, nominally, of the mainland north of the forty-ninth parallel, known within the fur trade as New Caledonia. There and on Vancouver Island, as of 1849, the HBC operated fifteen trading posts that stretched across the future province of British Columbia: Connolly Post, Fort Alexandria, Fort Babine, Fort George, Fort Hope, Fort Langley, Fort Okanogan, Fort St. James, Fort Simpson, Fort Stikine, Fort Victoria, Fraser Lake, Kootenay Post, McLeod Lake, and the Thompson River/Kamloops Post.33

The HBC’s efforts to “colonize” Vancouver Island were, as set out in 1849, to be assessed every two years as to the number of settlers and amount of land sold, with the possibility for termination of the grant by the British government after five years. The terms were straightforward:

"The condition of the grant is declared to be the colonization of the island. With this object the Company is bound to dispose of the land in question at a reasonable price, and to expend all the sums they may receive for land or minerals (after the deduction of not more than 10 per cent, for profit) on the colonization of the island.

"

At the end of ten years, “the Government may repurchase the land on repayment of the sums expended by the Company on the island and the value of their establishments.”34

Encouraging non-Indigenous settlement

Between 1848 and 1852, the HBC brought a total of “270 males with 80 females and 84 children” to Vancouver Island as its own employees. The men, “chiefly agricultural labourers,” were promised that “if they perform their contracts of service in a satisfactory manner, they shall receive a reward of £25 over and above their wages, to be paid to them in land at the price of 20/- per acre, so that it may be expected that many of them will become settlers.”35 Eighty of these employee settlers, nearly all of them men, and including medical doctor John Sebastian Helmcken, arrived in March 1850 after a six-month voyage from England on the HBC’s vessel the Norman Morison. The ship returned in 1852 with twenty-five more arrivals, again almost all men, and the next year with 115, ranging from couples with children to single men contracted by the HBC for five years, to be rewarded with 25 acres of land if hired as labourers, 50 acres if as tradesmen.36 A grid of streets was laid out in Victoria in 1852, and “town lots” were offered for sale.

According to a census taken in the summer of 1855 and reported to the Colonial Office, Vancouver Island’s “native Indian” population was “about 22,000,” raised in a closer count a year later to 25,873.37 The Island’s “white” population, which had “not much increased for the last twelve months by spontaneous emigration,” stood in 1855 at 774. Of these, 232 lived in Victoria proper; 150 in Nanaimo, a hundred kilometres to the north, where the HBC was mining recently discovered coal deposits; and the other 400 or so were scattered among a variety of locations. The 1855 count of the white population turned up 1,418 acres of improved land with 243 dwelling houses and 39 shops. There were 284 horses, 240 milch cows, 206 oxen, 560 other cattle, 6,214 sheep, and 1,010 swine.38 This “distant Dependency,” to use the Colonial Office’s description, was in the larger scheme of things among the tiniest of British possessions.39

Another of James Douglas’s responsibilities was to create governing structures consistent with Colonial Office practice around the world. Writing in October 1851, Douglas noted that he had appointed someone to fill the position he previously held on the existing three-man “Council of this Island,” left vacant by his appointment as governor, but there things came to a halt.40 It was, he explained a year later, inexpedient to do more “until the population increases, and there be a sufficient number of persons of education and intelligence in the Colony.”41 Douglas acknowledged in July 1853 that “we have done nothing of any importance in the way of legislating for the Colony.”42

Indicative of the slow increase in white male British residents, only in the spring of 1855 could the Hudson’s Bay Company report that there were “more than Forty Freeholders possessed of twenty acres of land, and upwards, which the Regulations have declared to be the qualification of voters for Members of [the House of] Assembly.”43 Colonial Office officials were not so sure about the numbers, being well aware of Douglas’s tendency to conflate retired and present HBC employees with “colonists” in the usual sense of that word. One of the officials said as much in a minute on another letter. “I confess that I think the establishment of [a] representative System under the circumstances of the Island wd be little better than a parody, especially if true as sometimes asserted that very nearly the whole of the occupiers [of land] are Servants of the Cy living on its pay.”44

However, Douglas’s looser approach to settlement won out over the alternative, seriously considered within the Colonial Office, of removing Vancouver Island from HBC oversight because the Company had not fulfilled the conditions of the grant by 1854, which was five years after the agreement was signed. From its perspective, the decision to leave the colony under HBC control had less to do with Douglas than with American influence:

"It is difficult to say whether the more serious risk of collision with the American population of Oregon is greater or less than it wd be if the Island were resumed [by Britain] from the Cy. Recent despatches show that there are inflammable Materials on both sides especially the American. In my opinion the only real strength for such a community is to be sought in increasing population & if the Island were resumed [to Britain] I shd think it wise to give small lots—of 5 or 10 acres to a reasonable number of actual occupants at a mere nominal price—resumable if not brought fully into cultivation.45

"

The Colonial Office’s solution was the establishment on Vancouver Island of a “legislative authority,” independent of the Hudson’s Bay Company. This was enacted in 1856 in the form of an eight-member elected Legislative Assembly.46

Writing to the Colonial Office in June 1856, Douglas’s mind was more immediately on “a large arrival of” Indigenous people from the Queen Charlotte Islands, located on the northwest coast of Vancouver Island and known today as Haida Gwaii.47 Six weeks later Douglas reported, alongside a brief mention of “a smouldering volcano” in the form of “great numbers of northern [Indigenous people],” the good news that “the propositions in respect to the convening and constitution of the Assembly were approved and passed without alteration, at the meeting of the 9th of June.” However, “in order to suit the circumstances of the Colony, the property qualification of Members [of the Assembly]” had been reduced, given that “a higher standard of qualification would have disqualified all the present representatives.”48

Over half of these qualified to vote had arrived with the fur trade, being one-time officers or employees grateful for the opportunity to settle down with their families, almost always with Indigenous or part Indigenous women, in this remote British colony.49 As to why it was not possible also to secure independent settlers in numbers, Andrew Colvile, deputy governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, pointed out to the Colonial Office in 1855 four “peculiar difficulties,” namely:

"The great distance of the Island from this country, and consequent length of the voyage, the high rate of wages given in the Gold districts of California which unsettles the minds of the labouring population, the system of free grants of land that prevails on the opposite shore of the Straits of De Fuca, and the distance from any market, except for those on American territory where the Import duties are almost prohibitory.50

"

As for Vancouver Island’s inaugural Legislative Assembly meeting in August 1856, “the affair passed off quietly, and did not appear to excite much interest among the lower orders,” in Douglas’s words.51 Among the seven men comprising the first House of Assembly was Thomas Skinner, an English gentleman enticed to manage an HBC subsidiary and arriving with his family in time to do so.52

The Assembly’s election as Speaker of John Sebastian Helmcken, by now married to Douglas’s eldest daughter, Cecilia, was, whether intended or not, a conciliatory gesture to Douglas, who had initially opposed the idea of a Legislative Assembly that might hamper his actions as governor and HBC officer. On his arrival in 1850, the resourceful Helmcken had been dispatched to Prince Rupert on the north coast, but he was soon transferred to Vancouver Island, where he continued to practise medicine while engaging in colonial politics. He would hold the Speaker’s position until a united British Columbia joined Canada a decade and a half later in 1871.

Managing the economy

Douglas’s management of the Vancouver Island economy was no easy matter, hemmed in as it was by the HBC and the fur trade, and to the south by the United States. Mindful of his double masters of the HBC and the Colonial Office, Douglas early on marked out for the former the boundaries of twenty-five square miles on the southeast corner of Vancouver Island which the HBC had “held as their exclusive property” since the founding of Fort Victoria in 1843. Douglas pointed out defensively to the Colonial Office in 1852 that the Company had “expended large sums of money in bringing the land into cultivation.” It also used the land as a cattle range and “as a protection from the intrusion of American citizens,” who were at this point in time daily expected on Vancouvers Island.53 In spite of the “large sums” spent on cultivation, Douglas also acknowledged “a deficiency of bread stuffs for the consumption of the Colony” due to so few farms, just thirty-one by his count.54

Another of Douglas’s tasks as governor was to educate the mother country respecting the geography and economy of Vancouver Island. Douglas pointed out, in the summer of 1852, the island’s “most unfortunate position for Trade; at the distance of more than 4000 miles from the nearest British possession and separated from the Mother Country by half the circumference of the Globe.” In consequence, “it has no available outlet for its productions, consisting of Salt-fish, Deals, Limestone and Spars for Masts, which with the exception of the last will do little more than defray the expensive transport to Great Britain.”55 Three years later, in 1855, the island’s limited “foreign trade” was “confined to the Sandwich Islands [Hawaiian Islands] and the Ports of California.”56

Douglas took particular pleasure in confirming reports of “the existence of coal” at a place “named ‘Nanymo’ after the Tribe” of the same name. Douglas’s initial letter of August 1852 had sent Colonial Office officials into a veritable tizzy of relief and anticipation that maybe this faraway place was not as useless as it seemed to be, as the under-secretary of state for the colonies described at length:

"I do not think the attention of the Govt of this country has been sufficiently directed to the fact of the very great importance, of which the possession of Queen Charlottes & Vancouver islands may have to this country. Whatever the event of the rumoured and partially proved discovery of gold in the former—the possession of coal in Vancouvers Island—a solitary instance along the long line of coast of the two Americas (as far as we have yet discovered), together with its favorable position as regard St Francisco & the whole Western coast of N America ought to make it the centre of the Pacific commerce.57

"

The HBC exploited the find to its own gain. “Twenty three Coal Miners with their families forming collectively about 109 persons sent from England, by the Hudson’s Bay Company, for their coal works at Nanaimo,” was “the largest accession of white inhabitants the Colony” received in 1855, Douglas informed the Colonial Office.58

Minding the United States and Russia

It was not only the Colonial Office, the Hudson’s Bay Company, Indigenous peoples, and a handful of settlers that Douglas had to mind, but also Vancouver Island’s neighbour to the south. One of the most persistent irritants over his dozen years in charge was American unwillingness to accept the forty-ninth parallel as a forever border—and the less willing they were to accept the border, the more uncertain the colony’s future became.

Far more rapid white settlement to the south exacerbated the determination of both the United States government and individual Americans to fill in the remainder of the North American west coast. The pressure intensified after the 1846 boundary agreement, when the United States acquired the large hunk of land that became the American states of Oregon and Washington, as well as small parts of neighbouring states. As well, California, which had been taken from Mexico by force, became an American territory in 1848, and in 1850 a state.

For a short time in the 1850s Russia, to the north and west, was also a concern. The Crimean War was underway in Europe, and in the winter of 1854–1855 there were skirmishes between Anglo-French and Russian forces on the Kamchatka Peninsula lying west of Alaska. The British Navy established a base at Esquimalt to service its ships and provide medical care for battle casualties.

Indicative of the swirling course of events are three 1854 letters to the Colonial Office, two from Douglas describing Vancouver Islanders’ fear of “a descent by the Russians”; the other containing a minute that asks whether “it is desirable the present state of things should longer continue, with Russia on one side of the little settlement & the U.S. on the other.”59 Among Douglas’s ongoing responsibilities as governor, the foremost was to keep an acquisitive United States at bay. Not only were many Americans in and out of the political realm convinced they should have acquired the entirety of the Pacific Northwest in 1846, and better late than never, but a gold rush to California beginning in 1848 grew interest in similar locales where riches might be had.

The tension was ever present. Douglas’s letter of October 31, 1851, accepting the position of governor, described in its final paragraphs how “the natives have discovered Gold in Englefield Bay, on the West Coast of Queen Charlottes Island,” in conditions similar to those unleashing the California gold rush. Not only that, but “several American vessels are fitting out in the Columbia [River in American territory] for Queen Charlottes Island for the purpose of digging Gold.”60

Douglas sought the Colonial Office’s advice respecting Queen Charlotte’s Island, today known as Haida Gwaii, only to be sidelined on the grounds that it “is not within the government of Vancouver’s Island,” with no apparent interest being expressed by the Colonial Office as to which country’s territory it was.61 Douglas’s follow-up letter, written before he received a response to its predecessor, reported on vessels “chartered by large bodies of American Adventurers” who, if they found gold, intended “to colonize the Island, and establish an independent Government until by force or fraud they become annexed by the United States.” While one of these ships was wrecked and the other “intimidated by the hostile appearance of the Natives,”62 Douglas remained uneasy as to what might ensue the next time around—and his fears were not allayed on receipt of a return letter from the Colonial Office stating:

"With regard to the discovery of Gold on the West Coast of Queen Charlotte’s Island, I do not consider that it would be expedient to issue any prohibitions against the resort thither of Foreign Vessels. Were there no other objection to such a step it would be a sufficient reason against it that Her Majesty’s Government are not prepared to send there a force to give effect to the prohibition.63

"

However, the Colonial Office had a change of heart. Even before Douglas reported in April 1852 that two American vessels calling at “Gold Harbour” on Queen Charlotte’s Island had “been beaten off by the Natives; though the American force was considerable, and well armed,”64 the Office had “directed the attention of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty to the necessity which appears to exist for stationing a Vessel of War off Queen Charlotte’s Island.”65 This situation was resolved, at least for the moment, but others were in the offing.

Describing three years later in 1855 “the deplorable state of American Oregon, which is now involved in a disastrous war, with the native Tribes of that country, which appear to be animated with a rancorous hatred of American domination,” Douglas expressed relief as to how their northern counterparts “entertain a high degree of respect for the British name.” In a follow-up letter he reported “no change observable in their demeanour towards the British settlements.”66 Respecting Vancouver Island, a realistic Colonial Office official minuted on the earlier letter, “I regret to say that the Settlement is totally destitute of a military force,” to which another added with a verbal sigh of relief how “one can have little doubt that the Yankees are really the aggressors.”67 The Colonial Office grew so concerned over “the disturbed state of relations between Indian and American Settlers in Oregon and the North West generally…in the vicinity of the British Territory,” it gave Douglas authority in early 1856 to act on his own volition as he thought best so as not “to endanger the peace of the community of Vancouver’s Island.”68

Come 1857, Douglas was caught up in another dispute with the United States. This time it was over San Juan and neighbouring islands, which had up to then been assumed to be British possessions by virtue of their proximity to Victoria, despite their being marked on maps of the day as crossing the agreed international boundary of the forty-ninth parallel. The dispute would fester, eventually going to international arbitration that in 1871 handed the San Juans to the United States.

A waiting game, with British Columbia in the balance

American proximity, alongside James Douglas’s apparent disinclination to grow Vancouver Island’s non-Indigenous population—the result of his dual mandates to sustain the HBC and to govern—were not lost on the Colonial Office. One official stated them baldly in a minute to the others in July 1856:

"It is time to consider what position the British Govt shd take with regard to this Dependency having in view the probable extension of population on the American frontier…it may be doubted whether this island will remain British if there is not an influx of British population & it does not appear that the practical effect of the present system is to attract population.69

"

From the Colonial Office’s perspective, Vancouver Island had become a waiting game, as one official almost gleefully reminded the others in the fall of 1857 respecting the upcoming termination of the HBC’s grant of Vancouver Island, along with the expiry in 1859 of its exclusive right to trade with Indigenous peoples: “Yes—we must soon give a formal notice to the H.B. Company that we mean to disconnect Van Couvers Island with them & the whole question of its establishment will have to be considered.”70

It was in this uneasy set of circumstances, with no perceived best outcome with respect to the isolated and fragile British colony of Vancouver Island, that the unexpected intervened.

Responding to gold finds

James Douglas’s oversight of Vancouver Island took a different turn, as did the history of British Columbia, on the discovery in 1856 of gold on the mainland just across the Strait of Georgia from Vancouver Island. That a gold rush in the pattern of California in 1848 and Australia in 1851—which each attracted many thousands of prospective miners from around the world—would directly challenge the assumed authority of the HBC and of the Colonial Office had been in the back of James Douglas’s mind from the day he was appointed governor in 1851.

Douglas reported in April 1856 that “Gold has been found in considerable quantities within the British Territory on the Upper Columbia,” the location being on the mainland of the future British Columbia. Douglas had also been informed that “valuable deposits of Gold will be found in other parts of that country,” and so what, if anything, should he do about it?71 The Colonial Office’s return letter was, as earlier in respect to the Queen Charlottes, equivocal at best:

"In the absence of all effective machinery of Government, I conceive that it would be quite abortive to attempt to raise a Revenue from licenses to dig for Gold in that region. Indeed as Her Majesty’s Government do not at present look for a revenue from this distant quarter of the British dominions, so neither are they prepared to incur any expense on account of it. I must therefore leave it to your discretion to determine the best means of preserving order in the event of any considerable increase of population flocking into this new gold district.72

"

Douglas updated the Colonial Office a year later, July 15, 1857, “corroborating the former accounts” respecting the mainland, while acknowledging “yet a degree of uncertainty respecting the productiveness of those gold fields, for reports vary so much on that point, some parties representing the deposits as exceedingly rich, while others are of opinion, that they will not repay the labor and outlay of working, that I feel it would be premature for me to give a decided opinion on the subject.” Douglas described industrious local Indigenous peoples “expelling all the parties of gold diggers, composed chiefly of persons from the American Territories, who had forced an entrance into their country.”73 Long-time Colonial Office official and permanent under-secretary Herman Merivale minuted on the letter on September 21, 1857, as if foreseeing the future, that “if any interference is to take place” respecting the HBC’s exclusive right to trade west of the Rocky Mountains, “I believe it will be necessary to…form it into a colony.”74

Before receiving a response to his letters, Douglas wrote again at the end of December 1857 respecting “gold found in its natural place of deposit within the limits of Fraser’s River and Thompson’s River Districts” on the largely unknown mainland, over which he had no authority. Douglas once again pointed out “the exertions of the native Indian Tribes who having tasted the sweets of gold finding, are devoting much of their time and attention to the pursuit,” and also “much excitement among the population of the United States Territories of Washington and Oregon,” who he had no doubt would be “attracted thither with the return of the fine weather in spring.” Douglas was aware that his authority to act as needed in “Continental America…may perhaps be called into question,” even though he was, he pointed out to the Colonial Office, “invested with the authority, over the premises, of the Hudson’s Bay Company.”75

The Colonial Office in action

What to do, Douglas pointed out in his late December 1857 letter, was up to the Colonial Office. He enclosed a draft proclamation “declaring the rights of the crown in respect to gold…and forbidding all persons to dig or disturb the soil in search of Gold until authorized on that behalf by Her Majesty’s Colonial Government.” He continued, “Should Her Majesty’s Government not deem it advisable to enforce the rights of the Crown as set forth in the Proclamation, it may be allowed to fall to the ground, and to become a mere dead letter.”76 The future province of British Columbia hung in the balance.

By now the faraway Colonial Office had realized the importance of the situation, as Douglas hoped it would. The minutes on his letter of July 15, 1857, respecting forming the area of the reported gold finds into a colony, indicate that it had been decided “this question should be postponed until we receive more definite information,” which came in Douglas’s December letter.77 After that letter’s arrival in London on March 2, 1858, a warrant was drafted appointing Douglas to be “Lieutenant Governor of HM’s Territories and Possessions in North America which are bounded on the North by the 54h Degree of North Latitude, on the East by the Rocky Mountains and on the South by the 49h Degree of North Latitude.”78 The appointment as head of state would formally be offered to Douglas four months later in July 1858, whereas the decision to retain control of the future province with Douglas in charge had already been taken.

So it is that today’s British Columbia comes into view. It would do so politically with the creation, in 1858, of a second British colony encompassing the mainland, and it would do so spatially when the boundary between the United States and British territory extending from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean, running along the forty-ninth parallel, was surveyed.79 Looking ahead a decade and a half in time, it would be in 1871, a quarter of a century after the 1846 division of the Pacific Northwest, that British Columbia, by then including Vancouver Island, became the Canadian province it is today.

1 Following a meeting with HBC head Sir John Henry Pelly on September 23, 1846, Colonial Office permanent under-secretary Sir James Stephen minuted: “It appeared by his answers to the questions posed to him that the Hudson’s Bay Company are not able to define their Territory otherwise than by stating it to comprise all the Lands watered by the Rivers falling into Hudson Bay.” Minute by JS [Stephen] to Benjamin Hawes, under-secretary of state for the colonies, September 24, 1846, on Pelly to Henry George Grey, Earl Grey, secretary of state for the colonies, September 7, 1846, 1074, CO 305:1, The Colonial Despatches of Vancouver Island and British Columbia 1846–1871, Edition 2.2, ed. James Hendrickson and the Colonial Despatches project (Victoria, BC: University of Victoria), https://bcgenesis.uvic.ca/V465HB01.html. Colonial Office dispatches relating to Vancouver Island and British Columbia, 1846–1863, including the letters cited here, are accessible online at https://bcgenesis.uvic.ca/search.html. All letters cited here are available on the Colonial Despatches website unless otherwise noted. For tables giving information on names and initials that appear on the letters, see the Appendix.

2 Harold Adam Innis, The Fur Trade in Canada: An Introduction to Canadian Economic History (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1930), 115–16. On the terms of the licence, see Pelly to Earl Grey, September 7, 1846, 1074, CO 305:1. The HBC’s licence for exclusive trading with Indigenous people would be revoked on November 3, 1858, as noted in a letter from the secretary of state for the colonies, Edward George Earle Bulwer Lytton, to James Douglas, February 11, 1859, LAC RG7:G8C/7, 107.

3 The fur trade during this time period is detailed in Jean Barman, French Canadians, Furs, and Indigenous Women in the Making of the Pacific Northwest (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014).

4 For details and maps, see Bruce Watson, Lives Lived West of the Divide: A Biographical Dictionary of Fur Traders Working West of the Rockies, 1793–1858 (Kelowna, BC: University of British Columbia Okanagan, 2010), 996–1004.

5 Pelly to Earl Grey, September 7, 1846, 1074, CO 305:1.

6 Minute by G [Grey], September 25, 1846, on Pelly to Earl Grey, September 7, 1846, 1074, CO 305:1. This file contains the Colonial Office’s extensive internal correspondence seeking to sort out its position respecting the HBC.

7 Pelly to Hawes, October 24, 1846, 1301, CO 305:1. Like the September 7, 1846, file, this file contains extensive internal correspondence, including conversations with Pelly and a detailed physical description of Vancouver Island by James Douglas from 1842.

8 Pelly to Earl Grey, March 5, 1847, 333, CO 305:1.

9 Minute by JS [Stephen], March 8, 1847, on Pelly to Earl Grey, March 5, 1847, 333, CO 305:1.

10 Crowder & Maynard, the HBC’s solicitors in London, to Queen Victoria, “Grant of Territory in North America,” enclosed in Pelly to Earl Grey, March 5, 1847, CO 305:1.

11 Minute by JS [Stephen] to Hawes, March 8, 1848, on Pelly to Earl Grey, March 4, 1848, 471, CO 305:1; also Pelly to Earl Grey, Private, March 4, 1848, 475, CO 305:1, detailing the logic of the rejected proposal and its importance owing to American proximity; and for the Colonial Office’s thinking, the extensive minutes on Pelly to Earl Grey, September 7, 1846, CO 305:1.

12 Minutes by various clerks in the Colonial Office, including VJ [Vane Jadis], November 12; WD [William Dealtry], November 14; WR [William Robinson], November 16; HCN [Henry Charles Norris], November 16; SJB [Samuel Jasper Blunt], November 17, 1864, on Arthur Kennedy, governor of Vancouver Island, to Edward Cardwell, secretary of state for the colonies, No. 64, August 31, 1864, CO 305:23.

13 See Pelly to Earl Grey, September 13, 1848, CO 305:1, and April 16, 1851, CO 305:3.

14 James E. Hendrickson, “Richard Blanshard,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–), http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/blanshard_richard_12E.html. The characterization of Blanshard, quoted by Hendrickson, was from HBC chief factor James Douglas, who would be Blanshard’s successor.

15 Richard Blanshard, governor of Vancouver Island, to Earl Grey, June 15, 1850, 7378, CO 305:2.

16 Minutes by HM [Herman Merivale], BH [Hawes], and G [Grey] on Pelly to Earl Grey, April 16, 1851, 3118, CO 305:3.

17 Biographical information is taken from Margaret A. Ormsby, “Sir James Douglas,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/douglas_james_10E.html.

18 Donald J. Hauka, McGowan’s War (Vancouver: New Star, 2003).

19 Douglas to Henry Pelham Fiennes Pelham-Clinton, Duke of Newcastle, secretary of state for the colonies, July 28, 1853, CO 305:4, No. 9499.

20 Adele Perry, Colonial Relations: The Douglas-Connolly Family and the Nineteenth-Century Imperial World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015); John Adams, Old Square Toes and His Lady: The Life of James and Amelia Douglas (Victoria, BC: Horsdal & Schubart, 2001).

21 Earl Grey to Douglas, May 19, 1851, CO 410:1; Douglas to Earl Grey, October 31, 1851, 484, CO 305:3; date of response noted on the letter and also in Earl Grey to Douglas, February 4, 1852, LAC RG7:G8C/1.

22 Pelly to Hawes, November 22, 1849, 9816, CO 305:2.

23 Douglas to Sir John Pakington, secretary of state for war and the colonies, No. 7, August 27, 1852, 10199, CO 305:3.

24 BH [Hawes] to Earl Grey on Pelly to Earl Grey, April 16, 1851, 3118, CO 305:3; also Douglas to Newcastle, July 28, 1853, 9499, CO 305:4.

25 “Vancouver’s Island” and “Resolutions of the Hudson’s Bay Company: Colonization of Vancouver Island,” both attached to John Jervis and John Romilly to Earl Grey, July 10, 1849, CO 305:2. For the arrangement’s complexities, see Pelly to Hawes, October 24, 1846, 1301, CO 305:1, and November 22, 1849, 9816, CO 305:2.

26 Fairfax Moresby to the Admiralty, July 7, 1851, enclosed in J. Parker on behalf of the Admiralty to Frederick Peel, under-secretary of state for the colonies, November 28, 1851, 10075, CO 305:3. Respecting the requisite introduction of settlers, see among other Colonial Office correspondence T.W.C. Murdoch and C. Alexander Wood, of the Colonial Land and Emigration Office, to Herman Merivale, permanent under-secretary for the colonies, January 19, 1853, 535, CO 305:4.

27 Minute by VJ [Jadis], December 4, 1851, to Merivale on Parker to Peel, November 28, 1851, 10075, CO 305:3.

28 Stephen Royle, Company, Crown and Colony: The Hudson’s Bay Company and Territorial Endeavour in Western Canada (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011), 247.

29 Robert John Staines to Thomas Boys, July 6, 1852, enclosed in Boys to John Otway O’Connor Cuffe, 3rd Earl of Desart, under-secretary of state to the colonies, October 11, 1852, CO 305:3; see also “Robert John Staines,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/staines_robert_john_8E.html.

30 Douglas to Newcastle, July 28, 1853, CO 305:4, No. 9499.

31 Ormsby, “Sir James Douglas.”

32 See, among other sources, Hubert Howe Bancroft, History of British Columbia, vol. 32 of The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft (San Francisco: The History Company, 1887), 218.

33 For information on individual posts, including years of operation, see Watson, Lives Lived West of the Divide, 996–1095.

34 “Vancouver’s Island” and “Resolutions of the Hudson’s Bay Company: Colonization of Vancouver Island,” both attached to Jervis and Romilly to Earl Grey, July 10, 1849, CO 305:2. For the arrangement’s complexities, see Pelly to Hawes, October 24, 1846, 1301, CO 305:1, and November 22, 1849, 9816, CO 305:2. Respecting the negotiations that ensued at the end of the ten years, see, among other correspondence, S. Walcott, secretary to the colonial land and emigration commissioners, to T.F. Elliot, assistant under-secretary in the Colonial Office, October 14, 1861, CO 60:12; H.H. Berens, HBC governor, to Newcastle, November 7, 1861, CO 60:12.

35 Andrew Colvile, deputy governor of the HBC, to Pakington, November 24, 1852, CO 305:3.

36 “Ships List of Passengers for the ‘Norman Morison’ 1852” is available on the Vancouver Island GenWeb Project website, part of the British Columbia GenWeb database, at http://sites.rootsweb.com/%7Ebcvancou/ships/nmor53.htm.

37 Douglas to Lord John Russell, secretary of state for the colonies, August 21, 1855, 10048, CO 305:6; attachment to Douglas to Henry Labouchere, secretary of state for the colonies, October 20, 1856, 11582, CO 305:7.

38 Douglas to Russell, August 21, 1855, 10048, CO 305:6.

39 Minute by ABd [Arthur Blackwood] on Douglas to Russell, August 21, 1855, 10048, CO 305:6.

40 Douglas to Earl Grey, October 31, 1851, 484, CO 305:3.

41 Douglas to Pakington, November 11, 1852, 933, CO 305:3.

42 Indicative was Douglas “appointing a resident Magistrate for each district of the Colony, except Soke [Sooke near Victoria], where none of the Colonists are qualified in points of character or education to perform the duties of that responsible office.” See Douglas to Newcastle, July 28, 1853, 9499, CO 305:4.

43 Colvile to Merivale, April 16, 1855, CO 305:6.

44 Minute by JB [John Ball] to Sir William Molesworth, secretary of state for the colonies, August 3, 1855, on Colvile to Russell, June 9, 1855, 5599, CO 305:6.

45 Minute by JB [Ball], August 3, 1855, on Colvile to Russell, June 9, 1855, 5599, CO 305:6; for detail, see Arthur Johnstone Blackwood, senior clerk in the Colonial Office, to Newcastle, May 18, 1854, CO 305:5.

46 Minute by JB [Ball], August 3, 1855, on Colvile to Russell, June 9, 1855, 5599, CO 305:6; also Labouchere to Douglas, No. 5, February 28, 1856, LAC RG7:G8C/1; Douglas to Labouchere, No. 12, May 22, 1856, 1790, CO 305:7; Douglas to Labouchere, No. 14, June 7, 1856, CO 305:7; No. 23, July 22, 1856, CO 305:7; No. 29, October 31, 1856, 349, CO 305:7; No. 20, June 30, 1857, 8655, CO 305:8; and Frederic Rogers to Merivale, October 5, 1857, 9208, CO 305:8.

47 Douglas to Labouchere, No. 14, June 7, 1856, CO 305:7.

48 Douglas to Labouchere, No. 15, July 22, 1856, CO 305:7.

49 The list is attached to Colvile to Merivale, April 16, 1855, 3578, CO 305:6.

50 Colvile to Russell, June 9, 1855, CO 305:6.

51 Douglas to Labouchere, No. 19, August 20, 1856, CO 305:7.

52 The Skinner family is tracked in Jean Barman, Constance Lindsay Skinner: Writing on the Frontier (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003).

53 Douglas to Earl Grey, No. 5, June 25, 1852, 9099, CO 305:3.

54 Douglas to Newcastle, No. 9, Miscellaneous, October 24, 1853, 12345, CO 305:4.

55 Douglas to Pakington, No. 6, August 2, 1852, 9399, CO 305:3.

56 Douglas to Russell, No. 16, August 21, 1855, 10048, CO 305:6.

57 Minute by D [John Otway O’Connor Cuffe, 3d Earl of Desart] November 16, 1952, on Douglas to Pakington, No. 7, August 27, 1852, 10199, CO 305:3. A copy of the letter was immediately sent “to Admiralty and Geographical Society; and Land Bd,” and an extract “PRINTED FOR PARLIAMENT ‘Gold’—Queen Charlotte’s Island’ 18/53.”

58 Douglas to Russell, No. 16, August 21, 1855, 10048, CO 305:6.

59 Douglas to Newcastle, No. 35, August 17, 1854, CO 305:5; and minute by HM [Merivale], January 8, 1855, on A.E. Cockburn (UK attorney general) and Richard Bethell (UK solicitor general) to Sir George Grey, secretary of state for the colonies, December 28, 1854, CO 305:5.

60 Douglas to Earl Grey, October 31, 1851, 484, CO 305:3.

61 Minute by HM [Merivale], January 22, 1852, to Peel on Douglas to Earl Grey, October 31, 1851, 484, CO 305:3.

62 Douglas to Earl Grey, January 29, 1852, 3742, CO 305:3.

63 Earl Grey to Douglas, February 4, 1852, LAC RG7:G8C/1, 41.

64 Douglas to Earl Grey, April 15, 1852, 6485, CO 305:3.

65 Pakington to Douglas, March 18, 1852, LAC RG7:G8C/1, 62.

66 Douglas to Molesworth, No. 23, November 8, 1855, 380, CO 305:6; and Douglas to Sir George Grey, March 1, 1856, CO 305:7.

67 Minutes by ABd [Blackwood], July 16, 1856, and HM [Merivale] January 17, 1856, on Douglas to Molesworth, No. 23, November 8, 1855, 380, CO 305:6.

68 Labouchere to Douglas, Confidential, February 28, 1856, CO 410:1.

69 Minute by JB [Ball], July 21, 1856, on John Shepherd, deputy governor of the HBC, to Labouchere, July 14, 1856, 6281, CO 305:7.

70 Minute by HL [Labouchere] October 10, 1857, on Rogers to Merivale, October 5, 1857, 9208, CO 305:8.

71 Douglas to Labouchere, No. 10, April 16, 1856, 5815, CO 305:7.

72 Labouchere to Douglas, No. 14, August 4, 1856, LAC RG7:G8C/1.

73 Douglas to Labouchere, No. 22, July 15, 1857, 8657, CO 305:8.

74 Minute by HM [Merivale], September 21, 1857, on Douglas to Labouchere, No. 22, July 15, 1857, 8657, CO 305:8.

75 Douglas to Labouchere, No. 35, December 29, 1857, 2084, CO 305:8.

76 Douglas to Labouchere, No. 35, December 29, 1857, 2084, CO 305:8.

77 Minute by ABd [Blackwood], September 30, 1857, following on that of HM [Merivale], September 21, 1857, on Douglas to Labouchere, No. 22, July 15, 1857, 8657, CO 305:8.

78 Minute by ABd [Blackwood], February 3, 1858, in Douglas to Labouchere, No. 35, December 29, 1857, 2084, CO 305:8.

79 Edmund Hammond, Foreign Office, to Merivale, January 18, 1858, 635 NA, CO 6:2.