Chapter 6: Taking Gold Miners Seriously (1858–71)

Beneath the surface of events, as penned from the top down—be it by James Douglas, Bishop Hills, or from within the Colonial Office—everyday life from 1858 onward was, in the future British Columbia, all about gold miners. Given most prospective miners arrived via Victoria on Vancouver Island, and often retreated there over the winter months, which were generally unsuitable for gold mining, Vancouver Island’s residents might be said to have lived off miners, whereas Indigenous women sometimes lived with them. These circumstances are obvious in retrospect, just as they were obvious at the time to those willing to acknowledge what was happening. Victoria as the major area of non-Indigenous settlement in the future British Columbia depended on gold miners’ lucre, even as its residents sought to carry on their everyday lives as genteelly as possible.

It is also clear in retrospect that except for gold miners there would have been no gold rush, and except for the gold rush there would have been no mainland colony of British Columbia created in 1858. Whether Vancouver Island would have survived as a British colony cast on its own resources is impossible to know in retrospect. What is certain is that without the gold rush, today’s province would have had no immediate impetus to come into being in the form it did in 1871.

Given American aspirations to have the entirety of the North American west coast, more so after the United States acquired Alaska in 1867, today’s British Columbia mainland might well have gone to its southern neighbour then, if not earlier as compensation for Britain having permitted the breakaway southern states to construct ships on British territory during the American Civil War. Instead, the British colony of British Columbia, by then including Vancouver Island, became a province in 1871, thereby extending the reach of Canada across the North American continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. This development is to a considerable extent, if not wholly so, the gold miners’ legacy.

Gold miners mattered. They mattered a lot despite their almost total absence from the everyday written records originating in the Colonial Office except as objects to be critiqued and found wanting, as opposed to being actors in the course of events. If not for gold miners there would almost certainly have been no British Columbia.

Taking gold miners seriously

Taking British Columbia seriously is to take gold miners seriously. In doing so, it is necessary to keep in mind that they were real live persons in past time, not unlike ourselves in the present day.

Taking gold miners seriously is to rethink the long-held perspective, still visible in the historiography, that sees them as rowdy and contentious, as “fighty boys” to borrow my daughter’s childhood characterization of some of her schoolmates. Accounts from this perspective, including some recent monographs, run the danger of marginalizing gold miners to no real gain.1

Accounts that sideline gold miners from the time of their arrival in the future British Columbia, from 1858 onward, echo Vancouver Island governor James Douglas’s uncertain attitude toward them. Rather than accepting his observations, introduced in Chapter 3, as the way things were, we need to scrutinize them, reflecting on how his long career in the fur trade in charge of men over whom he had direct control on behalf of the London-based Hudson’s Bay Company caused him to find gold miners’ varied origins alien, even more so their independence of mind and action. Douglas perceived them as intruders, if not on his turf of Vancouver Island, then on the adjacent mainland which was, from his perspective, HBC turf. Writing near the end of 1858 following a trip to the goldfields, Douglas described how, despite “some of them no doubt respectable,” he had never seen “more ruffianly looking men” who “will require constant watching, until the English element preponderates.”2

It was not only Douglas, and thereby the Colonial Office, who marginalized gold miners as “so wild, so miscellaneous,” as they were described in the British House of Commons debate of July 1858 respecting the faraway mainland becoming a separate British colony.3 Gold rushes from 1848 in California and 1851 in Australia had already informed attitudes. Prospective miners’ willingness to cross long distances and unknown terrain in the hope of better lives for themselves and their families was far less newsworthy than the drama of the unexpected and its ensuing dangers.

The principal London newspaper, The Times, had not known initially what to make of the Fraser River gold rush. Its special correspondent Donald Fraser began reporting from San Francisco on June 4, 1858, his initial account reaching London in time to appear on Wednesday, August 4. The arrival of “a steamer from Vancouver’s Island with…news of the most glowing and extravagant tenor as to the richness of the new gold country in the British possessions” was irresistible as a news story, and its successors over the next number of years continued to be so.4

Fraser’s accounts were initially from San Francisco, where he was based, then from the future British Columbia, to which he speedily made his way. His articles sold newspapers, encouraging some readers to head to the gold rush, others to dream of doing so or at least to follow the remarkable course of events. The dates in the following excerpts indicate when stories were written as opposed to when they appeared in London newspapers.

"San Francisco, Monday, June 16, 1858. The fever all over the State is intense and few has escaped its contagion…the “rush” from San Francisco knows no cessation…From the 1st of this month till to-day (June 17th), seven sailing vessels and four steamers have left San Francisco, all for the new mines…One of the steamers carried away 1,000 persons, and another upwards to 1,200, and multitudes were left behind waiting for the next departure. There are still 13 vessels on the berth for the same destination, all filling with passengers and goods…The eagerness to get away is a mania…People seem to have suddenly come to the conclusion that it is their fate to go. “Going to Fraser’s River?” “Yes, oh, of course, I must go.”5

Victoria, Vancouver’s Island, Wednesday, September 9, 1858. Visited Murderer’s Bar, three to four miles below Fort Hope. Most of the miners are Cornish men, from California…Twenty log cabins erected…125 miners…The space allotted to each miner is 25 feet in width, running from the high water mark down into the river as far as he chooses to go. The miners are all satisfied with this arrangement, and all are quite ready to pay a license to Her Gracious Majesty of 1£ a-month…The miners all intend to winter on this bar in their log cabins. Provisions are cheap and abundant. They can buy plenty of salmon and potatoes from the Indians. The cost of living is $1 a-day to each man.6

"

Accounts tended to be at one and the same time dramatic and encouraging, if likely too honest for some readers:

"Up the river from Fort Hope, September 12, 1858. Indians complain that the whites abuse them sadly, take their [derogatory term for Indigenous women] away, shoot their children, and take their salmon by force. Some of the “whites” are sad dogs…

The work is not heavy; any ordinary man can do it. The time of work is generally 10 hours. Every man works much or little, according to the dictates of his own sweet will. Independence and hope make up the sum of his happiness.7

"

In his daily journal Anglican bishop George Hills, preaching in the gold fields, similarly pointed to miners’ figurative, if not also literal, authority over their everyday life:

"August 27, 1862. Everything must be in accordance with the will of the miners. The habits, the mode of speaking, the dress & such like…There nobody alters his dress from one day to another & so nobody stays away on that account for want of clothes. All come in their red shirts or such like also come to Worship.8

"

The gold rush’s appeal

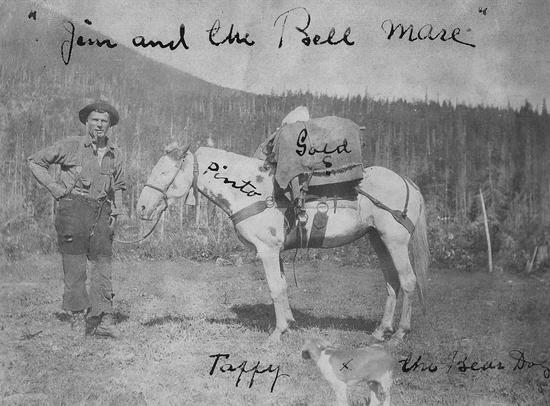

Part of the gold rush’s appeal lay in its being an ever-moving feast of possibilities for men daring to be caught up in its ethos, which was externalized in miners’ dress. Robert Burnaby, a thirty-year-old Englishman with pretensions to gentility, who arrived in Victoria in late 1858 to sample the gold rush, evoked in an early letter home the “diggers from Frazer River, frozen out now, but going back again in the spring, such picturesque looking fellows with fine manly faces bearded, with red and blue shirts, etc. just as you see in drawings of them,” by then circulating in the English press.9 The vivid impression captured by Sophia Cracroft, Lady Franklin’s niece (introduced in Chapter 5), after the two women travelled by steamer from Victoria to New Westminster, was more detailed but not dissimilar:

"Our fellow passengers were pretty numerous, chiefly miners & of many races. French, German & Spanish were spoken, to say nothing of unmitigated “Yankee.” Most of them had their pack of baggage, consisting of a roll of blankets to the cord of which was slung a frying pan, kettle & oilcan. Some possessed the luxury of a covering of waterproof cloth to the package. Every man had his revolver & many a large knife also, hanging from a leather belt. I should say that this mining costume in “highest style” consists of a red shirt (flannel), blue trowsers [sic], boots to the knees, and a broad brimmed felt hat, black, grey, or brown, with mustaches ad libitum.10

"

For a moment in time, gold miners could be who they would be, unfettered by the pretensions and assumptions of right behaviour whence they came.

The superiority of Englishness

Even as miners dressed similarly and were repeatedly so depicted, they brought with them a diversity of backgrounds, causing Governor James Douglas to lament “that so few of Her Majesty’s British subjects have yet participated in the rich harvests reaped in British Columbia.”11 On the other hand, a contemporary told Hills, which almost certainly gladdened his heart, that there were “amongst the Miners such books as Gibbon, Macaulay, Shakespeare & Plutarchs’ Lives.”12 Still read in the present day are Edward Gibbon’s History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, originally published in six volumes between 1776 and 1788; Thomas Babington Macaulay’s History of England from the Accession of James the Second in five volumes between 1849 and 1861; William Shakespeare’s plays; and Plutarch’s Lives of Noble Greeks and Romans.

That some gold miners were English was comforting to Hills and Douglas, and to lonely others. Writing in July 1860, half a year away from England, Hills enthused in his daily journal over an encounter at Canada Flat, which would become Lillooet, with “a company of 7 Englishmen” who “live in two log huts,” several from Cornwall, all arrived in British Columbia via California, out of touch with their family in “the old country” and “glad to talk about old England.”13

Douglas’s predisposition for all things English not unexpectedly contained a class component. Responding in 1861 to the suggestion “that a Magistrate should be appointed to reside on Admiral (or Salt Spring) Island” consequent on “an Indian disturbance,” Douglas prevaricated as to how “I have made it a rule to select those local Magistrates from the respectable class of Settlers,” but “none of the resident settlers on Salt Spring Island having either the status or intelligence requisite to enable them to serve the public with advantage in the capacity of local Justices, no appointment was, simply for that reason, made.”14 That such persons would be English was taken for granted.

A disdain of everyday miners extended to Douglas’s other actions, as with this assertion to the Colonial Office at the beginning of 1861:

"There is no prospect of material increase in Land Sales for 1861, except through the effect of emigration from Canada and Great Britain, as there is a very small farming population in the Colony; the working classes being chiefly miners, accustomed to excitement, fond of adventure, and entertaining generally a thorough contempt for the quiet pursuits of life.15

"

If miners could not be British, being Canadian was second best. To this preference might be added Douglas’s description three years later respecting the Members of Council he had just appointed for Vancouver Island that they were “gentlemen of education, approved loyalty, good estate, and high moral worth.”16

Attitudes from the top down assuming the superiority of Englishness almost inevitably loosened, at least somewhat, over time. Writing in 1865, British Columbia governor Frederick Seymour asserted how “the Majority of the population in Lytton, Quesnel Mouth, and I believe some other towns, is alien.” He was nonetheless willing, given “the central Government is sufficiently strong to enable me to do so with perfect safety to the Public,” to “propose allowing those not under allegiance to the British Crown a share in the management of these small municipalities.”17

Gold miners from their own perspectives

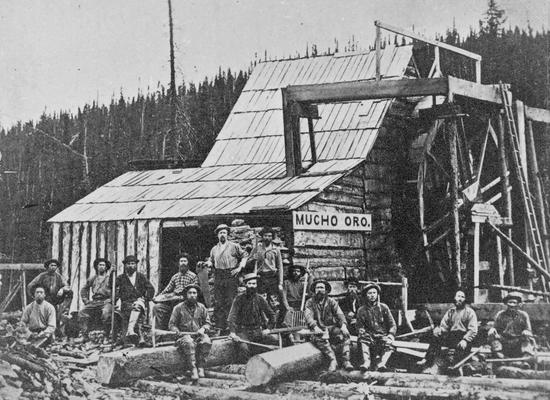

Douglas’s attitude says as much about Douglas as it does about gold miners, whether or not they came with reading material in tow. Once we take gold miners seriously, on their own terms, a more nuanced perspective comes into view. The gold rush gave a long generation of young and not-so-young men from around the world the opportunity to seek to become who they wanted to be, with greater freedom to do so than they would almost certainly have had whence they came. They could for at least a brief moment in time, perhaps for a lifetime, reimagine themselves. Everything seemed possible and eminently doable given, by one early description, “the Gold searching is principally carried on by Sluicing, which is effected by means of ditches constructed with great skill and sometimes at great length.”18

Very importantly, it was not only Douglas but also gold miners who perforce lived at least for a time between two worlds: that of their upbringing and that of an occupation which in the moment captured their attention. For those who were British in background, the transition from whence they came to where they were headed might have been the most difficult to navigate. Long-time Colonial Office employee Arthur Blackwood, not without reason, characterized a British Columbia resident about to visit England in 1864 as “coming home.”19

Families back home lost out, at least in the moment. Gold miners in British Columbia were beyond easy communication, and possibly had no communication at all, with the outside world until the completion of a telegraph line in the mid-1860s. During an evening stroll while preaching across the mainland in the summer of 1861, Bishop Hills came upon a miner in a solitary cabin at Lillooet who said he had a family in Cornwall with whom he had long since lost contact. “He talked of the roving and unsatisfactory life of the miner. He said many men got on hard but that they preferred it to some civilized existence. Some however went & became reckless.”20

Not all non-Indigenous men who set down in British Columbia originated as gold miners. Two days after his encounter in Lillooet, Bishop Hills, who travelled by horseback with a few others, passed by the holdings of Donald McLean, a well-educated Scot who, during his four decades as a Hudson’s Bay Company employee, had children with three different Indigenous women and who, rather than abandoning them when the HBC wanted to transfer him elsewhere, abandoned the fur trade to become a rancher around the Company’s post of Fort Kamloops. Another visitor at about this time considered “McLean’s Station, the best farm in the colony,” describing how “the enterprising and industrious proprietor has valuable stock of cattle” along with “fine turnips, cabbages, and scarlet-runners.”21 Hills found as much to praise as to query. Granted, “all of the children of Mr Mclean are from Indian mothers” and “the younger boys are fine children but wild as colts.” On the other hand, McLean “has some fine cattle” and assured Hills he “should be glad of visits if a clergyman could be provided & he wd see all things made comfortable for them.”22 It is fair to say Hills was, at least in the moment, charmed by a family setting he might otherwise have found wanting.

Hills’s conversation a few days later with a group of “English miners” gave him a dose of reality, so he penned in his daily journal:

"Miners seldom get rich all allowed. Many had fine opportunities & realized large returns for a time but seldom retained the results of their labour & good fortune…They were away from home ties & restraints of society so they gave themselves up to do whatever they were tempted to do—so gambling, drinking, several pleasures soon wasted the substance. They allowed that every man kept an Indian [woman].

"

As if to validate the miners’ perspectives, Hills noted, when he was talking soon after with the local storekeeper, “the impudent [derogatory term for Indigenous women] of whom he was ashamed & whom in vain he tried to get out of our sight,” but “she would not go.”23 Indigenous women, whatever the circumstances, had minds of their own.

A talk a week later with “a shoemaker” in Hope resulted in Hills being asked to have £20 sent to the man’s wife “through Archdeacon Hill at Chesterfield” in England, to which Hills agreed given “he seems a worthy man.”24 The Colonial Office files in London are awash with letters from families desperate not so much for money as for word, any word at all, from sons and husbands long since out of touch.25 How many gold miners disappeared from view by choice or circumstance is impossible to know.

The nature of gold mining

Whatever the time period, gold mining meant going where gold was to be had. Rushes were just that: mad dashes to the latest finds, the next one hopefully richer than its predecessors. Travelling up the Fraser River in November 1860, well-educated Englishman Robert Burnaby, who had arrived two years earlier with the customary gentleman’s letter of introduction from the secretary of state for the colonies, Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, to James Douglas, and had subsequently pursued this and that, observed in a letter home how “the ‘Bars’ [gravel ridges or bars extending across river mouths, hopefully containing gold flecks] which in ’58 were crowded with diggers are now quite deserted, seamed up with trenches and heaps of ‘dirt’ here and there, an occasional Chinaman may be seen rewashing the leavings.”26 A bit farther up the river Burnaby mused to his faraway mother:

"The last Bar before reaching Yale is called Hills Bar and this has been as productive of Gold as any place, not only in B. Columbia, but even in California. This used to be the headquarters of the Yankee rowdies [underlining in original]—and early in 1859 there was a serious disturbance there, it used to be quite a town, with half a dozen bars, two or three Billiard tables etc., but now it is no more than a heap of gravel, and all its wealth is taken away.27

"

The nature of gold mining was such that men reinvented themselves by chance or choice. For some it meant moving on to the next known find, then to the next, and so on. For others it meant returning home; for yet others, making new lives on the mainland or on Vancouver Island.

For Burnaby a shiny new mining option was coming into view. He described it optimistically to his sister in April 1861 from Victoria:

"We are now at the turning point of spring—when the island is most lovely—all the rocks, plains and woods turning with the prettiest wild flowers and flowering shrubs…With these flowers and sunshine our usual hopeful season arrives. In a “gold country” everything is at a standstill during the winter; the Miners cease working, come into town to “loaf” and spend their earnings—there is much talk of the past and hope for the future which bursts forth in a sort of excitement, when the start for the upper country begins. We have already been favoured with tremendous reports from the “Cariboo” country—a tract far up in B. Columbia.28

"

The news got better and better. Come October Burnaby enthused to his mother how “the news from the goldfields is as wonderful, as I always said it would be,” with “men coming down, daily almost now, who have gone up, without a penny, and bring down £500 to £1200, the result of six weeks or two month’s work.”29

Burnaby was not alone in his observations. After considerable assessment of routes, Judge Matthew Begbie observed at the beginning of 1863 how Williams Creek in the Cariboo was “the admitted centre of mining population, energy, and (up to the present time) riches and quantity of diggings.” There “houses were rapidly springing up at convenient intervals.”30

It was also the case that the nature of gold mining in the Cariboo in narrow, steep-sided, and isolated creek beds made it a business requiring extensive financial resources as opposed to mining’s earlier dependence on individuals’ hard work and good fortune. The Cariboo would be British Columbia’s last great gold rush destination, but of a very different kind than its predecessors.

Minding the gold rush

That the British Columbia gold rush proceeded as well as it did was due in good part to the two men initially in charge, James Douglas on site and Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton in faraway London, acting expeditiously separately and together. When, as described in Chapter 2, Lytton, the secretary of state for the colonies, made the case in the British House of Commons for today’s British Columbia mainland being made a new British colony, he drew on information in Douglas’s letters, along with his own literary bent, and on the powerful imagery of gold for the taking. Lytton excited the imagination by alluding to “settlers so wild, so miscellaneous, perhaps so transitory” and “persons of foreign nations and unknown character” of whom, he acknowledged, “few, if any, have any intention to become resident colonists and British subjects.” Lytton laid down a challenge respecting a new colony “eminently suited for civilized habitation and culture,” whose acquisition was too delicious for the Colonial Office to resist.31

Douglas was not then, or ever it seems, quite sure what to make of gold miners. His everyday relations seem to have been cordial, yet he repeatedly wrote otherwise in his letters to the Colonial Office, as on December 27, 1858: “I would hardly venture to give a decided opinion on the subject of recruiting a regular military Force, from the Gold Diggers of the Colony, as the men taking service would probably be composed of the idle and worthless classes.”32

Neither Lytton nor Douglas ventured much beneath the surface of events in respect to gold miners as fellow human beings. Douglas’s earlier oversight of the far-flung fur trade contributed to his outlook. When visiting the gold fields extending from today’s Fraser Valley through the Cariboo in central British Columbia, Douglas for the most part kept his distance from the miners, though a handful are mentioned by name and possibly engaged with Douglas in casual conversation, mostly because they were British or seemed so.

Likely influenced by Douglas’s assessments, the Colonial Office had no more truck with gold miners than was necessary. A minute by long-time clerk Arthur Blackwood on a February 2, 1863, letter from Douglas was indicative: “As for the miners they are only fit for digging and washing for gold.” They were the antithesis in Blackwood’s view to “persons of respectability.”33

Gold miners had, all the same, to be overseen. Across British Columbia this was done by regional gold commissioners. As defined by the Colonial Office in 1859, “the Gold Commissioner is to be a Justice of the Peace with power to try and settle summarily all mining disputes and abate encroachments.” His task was to oversee “the area for each free Miner being a square of one hundred feet,” and to “mark out plots of 5 acres for the occupation of the Miners as Gardens or residences, and other plots for the occupation of traders.”34 Commissioners were to report periodically to the governor of British Columbia. Two such reports from the summer of 1866, by which time the practice was firmly in place, are revealing as to what mattered on the ground respecting British Columbia’s foundational gold rush.

Peter O’Reilly, who had served in his previous life in the Irish Revenue Police, reported in June 1866 from French Creek in eastern British Columbia that “though the new gold fields have not been extended as much as expected,” there has still been “a very marked improvement.” The past winter had not treated men well. “No doubt the miners have suffered severely, as few were possessed of means sufficient to enable them to remain in the country, in consequence of the scarcity and high price asked of every article of consumption.”35

Cariboo gold commissioner William G. Cox, a Dublin banker seduced by the gold rush, described from Richfield, located near the principal Cariboo gold rush town of Barkerville, how its population is “steadily increasing both in white men and in Chinese,” the latter “spreading themselves over the country and appear to be doing remarkably well,…in fact I have not before seen such a general feeling of prosperity and satisfaction since I have been here…As a general rule the miners have nothing this season to complain of. The water in the creek is abundant without being troublesome. There is no sickness on the Creek and very few patients in the Hospital.”36

A year earlier, British Columbia’s governor Frederick Seymour had taken note on his visit to Williams Creek in the Cariboo of “a very creditable hospital supported by private contributions and a Government allowance of a thousand a year” that is “extremely clean and well managed.”37 Cox was similarly impressed a year later. “Grouse Creek still continues attractive, and is likely to rival Williams Creek in its richness and in their number of claims paying…there are about 400 men on the creek, and a Town is being rapidly built up. All appeared well satisfied and contented.”38

Estimating numbers of miners

However much we track individual gold miners and sites, it is when we turn to the numbers that we come to realize the British Columbia gold rush was a serious business for a lot of people. It played an important role, whatever the men’s origins, in the coming into being of the Canadian province we know today as British Columbia.

Parsing the numbers is also humbling in that they are at best only suggestive, given their limited scope and the toing-and-froing of the two colonies’ newcomer populations. Settlement as we have long tended to conceive it was not quick to come into being, except in Victoria, prior to British Columbia becoming a Canadian province in 1871.

Whatever the time period, gold miners came and went for a variety of reasons. Those given by miners departing at the end of the seminal 1858 season were “various, some having families to visit and business to settle in California, others dreading the supposed severity of winter weather, others alleging the scarcity and high price of provisions, none of them assigning as a reason for their departure the want of gold.”39 Writing the next spring, Douglas blamed earlier departures on the lack of an assay office to determine the value of gold that was mined so that “hundreds of miners worn out with the expense and delay so occasioned, headed in disgust to San Francisco” where their gold could be quickly assayed.40 Two months later Douglas added to the “various reasons for leaving the country…the high price of provisions, others, a desire to see their friends and to spend a few months comfortably in California; others the irregularity and shallowness of the diggings.”41

While overall numbers of arrivals in no way approached those of the earlier California and Australia rushes with their hundreds of thousands across a considerable number of years, they mattered, however imprecise the totals, to the course of events in what was until then a wholly Indigenous place apart from a smallish number of fur trade employees.

Population totals are at best suggestive. At the beginning of July 1858, James Douglas informed the Colonial Office that 10,573 passengers had so far arrived by water from San Francisco, which did not include those coming from elsewhere or by land routes.42 A month later he estimated “about 10,000 foreign miners, in Fraser’s River,” then the heart of the gold rush.43 The British consul in San Francisco reported in mid-October 1858 that 24,000 persons had that year left San Francisco for Victoria, with just 2,000 having so far returned.44

People moved around the British Columbia colony at will. In early November 1858, as the gold mining season was winding down, Douglas estimated, based on local reports, “the mining population in Fraser’s River” was:

| From Cornish Bar to Fort Yale | 4,000 |

| Fort Yale | 1,300 |

| Fort Hope | 500 |

| From Fort Yale to Lytton | 300 |

| Lytton | 900 |

| Fort Lytton to Fountain | 3,000 |

| Port Douglas & Harrison River | 600 |

| Total | 10,60045 |

Writing at the end of November Douglas reported that “the exodus from Fraser’s River continues at about the rate of 100 persons a week.”

In February 1860, based on information received from Douglas and others, the Colonial Office put numbers of miners, probably based on 1859 estimates, as:

| Between Hope and Yale | 600 |

| Yale and Fountain | 800 |

| Fountain and Alexandria | Unknown |

| Alexandria and Quesnel River | 1,00046 |

Two months later, with spring in the air, Douglas described “the constant accession to the population of British Columbia, by the influx of Miners.”47 Newcomers were not necessarily from Britain itself, but very possibly “foreign,” to use Douglas’s 1860 description as to how “unfortunately the population of this Colony is almost without exception foreign.”48

From then onward arrivals from China were dominant. Douglas informed the Colonial Office in January 1860 how “a detachment of 30 Chinese miners arrived yesterday, being it is supposed the pioneers of a large immigration of that people for British Columbia.”49 In April, Douglas described how “a great number of Chinese Miners [underlined in original] were…taking up mining claims on the River Bars, in the Lytton district, who are reputed to be remarkably quiet and orderly,” and more generally how “British Columbia is becoming highly attractive to the Chinese, who are arriving in great numbers—about 2000 having entered Frasers River since the beginning of the year and many more are expected from California and China.” Douglas was ambivalent, given that from his perspective “they are certainly not a desirable class of people, as a permanent population, but are for the present useful as labourers and as consumers, of a revenue paying character.”50 Come July 1860, “about a thousand white miners are working on Fraser’s River between Alexandria and Lytton and about four thousand Chinese miners are employed in the various districts of the Colony.”51 The Colonial Office reported how “the present fixed population—if so it can be called—of B. Columbia is probably 7000,” comprised of “3000 Whites” and “4000 Chinese,” while “the population of Vanc. Island in 1859 may be assumed as amounting to 3500.”52

In February 1861 “about 300 miners were then employed in that vicinity [of Hope], a large proportion of whom were Chinese; and that it was probable there would be a considerable emigration of that class towards Rock Creek and Shimilkomeen [Similkameen] in the course of the spring.” In the Yale District,

"the mining claims are with few exceptions in the hands of the Chinese, there being about Two Thousand of this people within the district. As a rule they have been successful and many have returned to their homes the possessors of from Two to Four thousand dollars. There are but few white miners…There are about Two Thousand Chinese in Yale and its environs alone. The cold weather has put a stop to all mining operations.53

"

An internal Colonial Office memorandum in March 1863 estimated the resident population of the mainland colony as:

| Scattered—Indians | say 10,000 |

| Chinese | say 5,000 |

| Miners (500 miles from N.West) | 5,000 |

| (350 miles from N.West) | 500 |

| Totals; | 20,50054 |

The calculation excluded “2000 persons scattered along the 500 miles between New Westminster and Cariboo and along the 350 miles between New Westminster and Rock Creek, and occupying, besides New Westminster and the Diggings, some half-dozen intermediate villages along these two lines.” Nothing was long term, assuredly, given “a find of Gold here or there may at any time change the relative importance of these different clusters of residents.” As well, “a few years will make a great difference,” given “the progress of the Country is very fast.”55 In July 1863 Douglas commended Chinese miners’ utility: “I have lately received intelligence that valuable discoveries of rich mining ground have been made by some Chinese Miners on the Banks and alluvial flats of Bridge River about 20 miles from the Town of Lillooet.”56

By February 1864 the population of Vancouver Island was estimated at “about 7500 persons exclusive of Indians,” which if accurate was likely linked to some one-time gold miners settling down there.57 Come October, Seymour, the new governor of British Columbia, put its white population at about seven thousand, with the Indigenous population at about sixty thousand.58

British Columbia’s non-Indigenous population

Whatever their origins and locations, the non-Indigenous population of the British Columbia colony in particular was, consequent on the gold rush, dramatically skewed by sex. A February 1860 British government report, likely based on numbers from James Douglas, noted: “The White population of the Colony amounts to 5000 men with scarcely any Women or Children.”59

Over the next several years, British Columbia non-Indigenous totals continued to be skewed by gender. According to Douglas, writing in the spring of 1861, “the actual population, Chinamen included, is about 10,000, besides a native Indian population exceeding 20,000,” respecting which “it must be remembered that all the white population are male adults,…there being no proportionate number of women or children,” by which he meant, and took for granted, white women and white children.60 Three years later, in March 1863, the Duke of Newcastle pointed out how “there is comparatively little white population in the Colony.”61 Four months later Douglas described “the immigration of this year so far consists of about four thousand five hundred persons (4,500 persons), chiefly able bodied men, exclusive of women and children, a class of which this Colony is still lamentably deficient.”62

Everyday consequences of a skewed gender balance in the white population

Male comradery in far distant locations went only so far. Given white women were mostly absent, the alternative for men wanting more was to turn to Indigenous women, with references to their doing so maligning the character of the men directly or by inference. Among early Colonial Office dispatches was an 1849 London newspaper article critiquing the HBC with respect to “the gross immorality which prevails in respect of the Indian women.”63

However much “white blood” mattered, and it certainly did, the practical option for many, perhaps most, newcomer men on their own and lonely was an Indigenous woman. Men who partnered with Indigenous women did so with differing consequences, depending in part on their placement in the social order, such as it was. While some men escaped scrutiny, others did not, especially if they were named to government positions. Among those “at present unknown to me” who incoming British Columbia governor Frederick Seymour appointed to the Legislative Council at the beginning of 1864 were Henry Maynard Ball of Lytton and John Carmichael Haynes, who had “managed admirably in the establishment of law and order among the miners.”64 Also named were William George Cox and John Boles Gaggin as assistant gold commissioners in the Cariboo.65

What is clear respecting these four men, each of whom merits attention as indicative of a larger phenomenon, is that personal qualities were perceived at least to some extent to override attitudes in the dominant white society that scorned the unions in which they engaged. Some might get a pass, as had James Douglas; others did not.

Two years after his arrival from England in 1859, thirty-six-year-old Henry Maynard Ball described himself as “an officer and gentleman, both civil & military.”66 He was also a married man, with a wife and two young sons back in England. Deemed ideal governance material, Ball was dispatched to Lytton as a justice of the peace and stipendiary magistrate.

By the spring of 1861 Ball’s future was, it seems, in shambles. On May 30 almost a hundred “merchants, miners and mechanics of Lytton City and District” petitioned Governor Douglas “that Judge Ball be removed from office immediately.” The first among numerous complaints was his “living with an Indian woman not married to him but keeping her as a public prostitute when he acknowledges that he has a wife & children in London City” to whom he sent support money quarterly.67

Ball denied all the complaints except for one: “There is one part of the charges, which I admit is true. I live with an Indian woman, who acts as my housekeeper, and as an excuse for this, I must state that I am isolated here without companions, without society, and have to pass my evenings in a dreary state of solitude—I therefore resorted to the alternative with which I am charged.”68

Ball’s defence had two parts.

First, “I have never allowed this connection to interfere with my public duties, in any way, and I defy any body to assert to the contrary.”

Secondly, “His Excellency cannot but observe that the signatories with few exceptions are those of foreigners and Chinamen, many of whom must have been ignorant of what they were signing, and His Excellency must also observe that the signatures of the most respectable portion of the inhabitants are wanting.”

A letter of support signed by nine local merchants made the same two points. “Though he like all men may have erred,” it had not interfered with “the gentleman’s reputation.” The ninety-three signatories on the petition represented “the seeming desires of a large portion of the floating population of Lytton.”69

Ball kept his job. He left Lytton four years later and remained in government service until his retirement in 1881.70

The second individual, twenty-eight-year-old Irishman John Carmichael Haynes, had come to British Columbia, like most others, for the gold. He was assisted on his arrival at the beginning of 1859 by his English uncle’s acquaintance with Chartres Brew, British Columbia’s recently appointed superintendent of police and gold commissioner.71 This connection got Haynes an almost immediate appointment as a constable in the heart of the gold rush.72 Two years later Haynes settled in Osoyoos in the Okanagan Valley, which would remain his home as he rose through the ranks as a magistrate, government official, and rancher, eventually owning a mighty twenty-two thousand acres of land.73 It was Haynes’s success in collecting customs duties and maintaining law and order that caused the governor to appoint him a member of the newly instituted Legislative Council of British Columbia in 1864.74

Haynes had two children with a Colville woman remembered as Julia: Mary Anne, born in 1866; and John Carmichael, born two years later, named after his father. The story long circulating has Haynes continuing to live in the bachelor quarters of the government building at Osoyoos while keeping, just a few yards away, a “separate little log house for his Indian ‘wife.’”75 As to Julia’s identity, Christine Quintasket, a Colville woman born about 1885, who published under the pen name “Mourning Dove” to wide acclaim that continues into the present day, is said to have had a white paternal grandfather.76 In one version of Quintasket’s story, he was “an Irishman” who “apparently married her Indian grandmother under the false pretenses of a tribal ceremony. His name was Haynes (or Haines).”77

Whatever the particulars, Haynes moved on. The same year his namesake son was born, Haynes, by then aged thirty-seven, married eighteen-year-old Charlotte Moresby, who had come to Victoria with her parents. Her father was a London barrister and younger brother of Sir Fairfax Moresby, admiral of the British Fleet. Charlotte died following the birth of their second child.78

Again Haynes moved on. In January 1875 he wed Emily Pittendrigh, who had come to British Columbia three years earlier with her family, her father distinguished by his service in the Crimean War.79 They would have six children together between 1875 and 1886, the oldest honoured as “the first white child born in Osoyoos.”80

Born in 1822 in Ireland, the third of the four men, William George Cox, had been a banker in Dublin before deciding he had had enough and moving to New York with his bride. Within the year she returned home, Cox having been enticed west by the British Columbia gold rush. Arriving with a testimonial to colonial surveyor J.D. Pemberton, Cox quickly rose in status…with one wrinkle.81 His wife tracked him down. Her letters demanded financial support even as he was caught up with an Indigenous woman he described “so sweetly” in a letter to his brother back home in Ireland as “nice & delicate and in native simplicity refined” [underlining in original].82 However long that relationship lasted, she at some point disappeared from view.

Cox’s position as a member of the British Columbia Legislative Assembly in 1867 and 1868 could not shield him from his wife’s wrath in the form of letters to all and sundry. As summed up by Helmcken: “Cox was a marked man whether on account of his vote or outside relations I know not. Letters came from his wife anyhow to the Government asserting her destitution. Cox went to California…The further history and end of poor Cox—I do not remember.”83

The fourth individual, John Boles Gaggin, was yet another Irishman, in his case from a “most respectable” family, who prior to heading to British Columbia had served in the Royal Cork Artillery Militia. Through family connections, he wrangled a letter from the secretary of state for the colonies, Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, “in favour of a Mr John Gaggin of the Royal Cork Artillery…to certify that he is a respectable person.”84 Gaggin was thereupon shortly after his arrival in April 1859 appointed chief constable in Yale, becoming in October the magistrate and assistant gold commissioner at Douglas.

Visiting the settlement at Douglas two and a half years later in May 1862, Bishop Hills was in his daily journal not kind to Gaggin. As to the reason:

"Almost every man in Douglas lives with an Indian woman. The Magistrate Mr. Gaggin is not an exception from the immorality. Recently the constable Humphreys was ordered to a distance by the Magistrate. The Indian woman he lived with was named Lucy, by whom he had a child. He proposed to take her with him. The magistrate was for some reason opposed. [The constable asked,] May I depend upon your honour that she shall be safe during my absence. The magistrate promised such should be the case. He violated the promise & induced the woman to come to him.85

"

Gaggin was dismissed from his position when Vancouver Island and British Columbia were united in 1866, which reduced the number of appointed positions.86

Indigenous women had not fared well in any of the four cases. They were expendable.

Turning to the Cariboo

The Cariboo gold rush beginning in 1861 was an afterthought to the 1858 British Columbia gold rush that had garnered headlines around the world, even though it was distinctive by virtue of its remote location. Compared to the older gold rush, mining in the northerly, increasingly favoured Cariboo was almost wholly seasonal. Douglas reported in February 1863 “the great body of Miners having left the District on the approach of winter,…causing the suspension of work for nearly seven months in the year.” There remained over the winter of 1862–63 at the most 350 men, which Douglas attributed to “the scarcity and high prices of food.”87 The upside was, from Douglas’s perspective, twofold: “rendering agriculture a more attractive pursuit and teaching settlers by the inducement of cheap land and high prices to give up the mines for the more certain realization of the farm.”88

As the next winter approached, Douglas wrote in November 1863 how “it is thought that a considerable number of people will remain here during the winter months—it is generally said 1000, but this I doubt, many who have almost made up their minds to remain will I think fly as soon as the severe weather sets in.” Indicative of miners’ uncertainty, Douglas added in the same letter, “the miners are now retreating in great numbers from Caribou [sic] and other remote Districts of the Colony on account of the apprehended severity of winter.”89 Writing in May 1865, Douglas’s successor as governor of British Columbia, Frederick Seymour, similarly lamented how “the Upper Country is almost deserted in the winter. The Miners have left the Colony. The communications are closed.”90

Miners thinking of settling down

For many miners, if not all of them, at the time they arrived the British Columbia gold rush was in their heart of hearts a passing fancy. They anticipated returning home richer than when they came, or moving on to some more interesting setting than British Columbia or Vancouver Island, both very much still in the making as opposed to being already made.

Most men soon departed, but others did not. They came for gold, but what they found was a place of being to call their own. The attractions were various, possibly including an Indigenous woman with whom to partner, along with a piece of land to know as their own in a valley, along a plain, or on an island. So it was that the place we know as British Columbia began to come into being.

Miners’ transformations were in their essence a matter of individual initiative related to circumstances and possibilities. Some miners were from early on at least thinking of settling down in the interim if not for longer. So gold miners contributed to the well-being of British Columbia for purposes familiar or convenient to them. Douglas reported in June 1859 respecting the completion of “a safe, easy, and comparatively inexpensive route into the interior of British Columbia,” how “the people of Port Douglas have expressed their willingness to aid either by their personal labour or by pecuniary contributions in the important work, as however none of them are wealthy, their contributions will not be great but their zeal for the progress and prosperity of the country is encouraging to us and very honorable to themselves.”91 In April 1860, in connection with the construction of a portion of his long-sought road, Douglas described the use of “the larger Lillooet Lake as a water communication,” mentioning specifically how “the application of some enterprising settlers to run a Steamer without any special privilege on the larger Lillooet Lake has been granted, and will greatly facilitate transport” given “an excellent mule trail 30 miles in length with substantial bridges over all the rivers [has] connected the larger Lillooet Lake with Lake Anderson.”92

Travelling in July 1861 from Hope to New Westminster, by which time it was legally possible to take up land, Bishop Hills “observed considerable open land on either side of the Fraser & many cabins as signs of preemption, much land especially near Langley on both sides.”93 Taken “over in Mr Brown’s boat” to his farm opposite New Westminster, Hills was so impressed he included the story in his daily journal:

"He began in April, & has now some 13 acres either under cultivation or ready. There are some 5 acres of potatoes, a large portion ready for use, though put in only in May. Swedes turnips who are first coming up also. There are 11 sorts of vegetables also Cucumbers. The land is rich loam with clay bottom & if the water can be kept out must become very valuable. There is about 300 acres of such land. If New Westminster goes on—this will be worth in my opinion a large sum in 5 years.94

"

The non-Indigenous population at New Westminster as elsewhere was sharply differentiated by gender. A census taken a couple of months earlier in April 1861 “found there 290 persons, of these about 30 only are women (not checking female children).”95

The passage of time made miners more likely to stick around. According to Vancouver Island governor Arthur Kennedy, over the winter of 1865–66 “a larger number of miners wintered at the mines than theretofore,” whereas previously most miners had retreated over the winter to Victoria or California.96 A year later British Columbia governor Frederick Seymour wrote in his report of a visit to the gold fields how “the miners are doing well & a population is settling down in Cariboo & its neighbourhood.”97 Judge Begbie was less confident, writing following his own visit a few weeks later as part of his regular circuit: “Not much gold taken out lately—and the prospects of a large out-turn…have quite changed. Many hundreds of men were thrown out of work i.e. one fourth or more of our efficient population” with “a couple of thousand men at work mining.”98 There would be an even greater contraction when on September 16, 1868, Barkerville was destroyed by fire, although rebuilding began almost immediately in what was a tribute to the sturdy way of life that had grown up there.99

More than elsewhere, due to distance, Cariboo miners for the most part got on with their lives on their own terms. The Cariboo was British Columbia’s last great gold rush destination, and by this time the gaze of the dominant society had lessened. Gold miners had lost much of their initial status as unwanted outsiders.

1 Among earlier monographs that come to mind are D.W. Higgins’s The Mystic Spring and Other Tales of Western Life (Toronto: William Briggs, 1904) and his The Passing of a Race and More Tales of Western Life (Toronto: William Briggs, 1905), partially reprinted in David William Higgins, Tales of a Pioneer Journalist: From Gold Rush to Government Street in 19th Century Victoria (Surrey, BC: Heritage House, 1996). Recent accounts include in alphabetical order Marie Elliott, Gold in British Columbia: Discovery to Confederation (Vancouver: Ronsdale Press, 2019); Donald J. Hauka, McGowan’s War (Vancouver: New Star Books, 2003); Christopher Herbert, Gold Rush Manliness: Race and Gender on the Pacific Slope (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2018); Robert Hogg, Men and Manliness on the Frontier: Queensland and British Columbia in the Mid-Nineteenth Century (London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012); and Daniel Marshall, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New Eldorado (Vancouver: Ronsdale Press, 2018).

2 Douglas to Merivale, Private, October 29, 1858, 586, CO 60:1.

3 Speech by Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, July 8, 1858, House of Commons, Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates, vol. 151, 1090–1121.

4 Donald Fraser, “Articles on British Columbia Printed in the London Times, Aug. 4, 1858–Aug. 15, 1862,” BC Archives, E/B/F86 (hereafter “Donald Fraser Articles”).

5 Donald Fraser, London Times, June 16, 1858, in Donald Fraser Articles.

6 Donald Fraser, London Times, November 30, 1858, in Donald Fraser Articles.

7 Donald Fraser, London Times, September 12, 1858, in Donald Fraser Articles.

8 April 27, 1862, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861–62: 41, in typescript in Ecclesiastical Province of British Columbia, Archives.

9 Robert Burnaby to his mother, December 26, 1858, in Anne Burnaby McLeod and Pixie McGeachie, Land of Promise: Robert Burnaby’s Letters from Colonial British Columbia (Burnaby, BC: City of Burnaby, 2002), 59.

10 Sophia Cracroft, March 5, 1861, in letter reproduced in Dorothy Blakey Smith, ed., Lady Franklin Visits the Pacific Northwest: Being Extracts from the Letters of Miss Sophia Cracroft, Sir John Franklin’s Niece, February to April 1861 and April to July 1870 (Victoria, BC: Provincial Archives of British Columbia, 1974), 38.

11 Douglas to Newcastle, Separate, September 16, 1861, CO 60:11.

12 April 30, 1862, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861–62: 42.

13 July 7, 1860, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1860: 154.

14 Douglas to Newcastle, No. 5, Civil, January 8, 1861, CO 305:17.

15 Douglas to Newcastle, No. 7, Financial, January 26, 1861, CO 60:10.

16 Douglas to Newcastle, No. 15, Legislative, February 14, 1862, CO 305:17.

17 Seymour to Cardwell, No. 135, May 17, 1865, CO 60:71.

18 Murdoch and Rogers, Colonial Land and Emigration Office, to Merivale, February 7, 1860, CO 60:9.

19 Minute by ABd [Blackwood], July 27, 1864, on Seymour to Newcastle, No. 6, May 19, 1864, CO 60:18.

20 June 17, 1861, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861: 80.

21 W. Champness, To Cariboo and Back in 1862 (Fairfield, WA: Ye Galleon Press, 1972; orig. 1865), 86.

22 June 20, 1861, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861: 81.

23 June 26, 1861, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861: 88–89.

24 July 1, 1861, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861: 92–93.

25 Though sometimes they were seeking money. For example, Elizabeth Ross, Inverness, to Cardwell, May 5, 1864, CO 60:20, was inquiring about money owed her deceased son by his employer, with minutes on the letter suggesting some ways for her to apply for help through governmental or private means.

26 Robert Burnaby to his mother, November 9, 1860, in McLeod and McGeachie, Land of Promise, 150; also Madge Wolfenden, “Robert Burnaby,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/burnaby_robert_10E.html.

27 Burnaby to his mother, November 9, 1860, in McLeod and McGeachie, Land of Promise, 152.

28 Burnaby to his sister Harriet, April 15, 1861, in McLeod and McGeachie, Land of Promise, 159–60.

29 Burnaby to his mother, October 6, 1861, in McLeod and McGeachie, Land of Promise, 162.

30 “Judge Begbie to Colonial Secretary,” January 19, 1863, enclosed in Douglas to Newcastle, No. 9, Miscellaneous, February 2, 1863, CO 60:15.

31 Speech by Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, July 8, 1858, House of Commons, Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates, vol. 151, 1090–121.

32 Douglas to Lytton, No. 56, December 27, 1858, CO 60:1.

33 Minute by ABd [Blackwood], April 1, 1863, on Douglas to Newcastle, No. 9, Miscellaneous, February 2, 1863, CO 60:15.

34 Rogers to Merivale, November 17, 1859, CO 60:5; report by Peter O’Reilly, gold commissioner, December 4, 1862, enclosed in Douglas to Newcastle, Separate, December 4, 1862, CO 60:13.

35 Report by O’Reilly, June 30, 1866, enclosed in Birch to Cardwell, No. 52, July 10, 1866, CO 60:25.

36 Report by William G. Cox, gold commissioner, July 1, 1866, enclosed in Birch to Cardwell, No. 52, July 10, 1866, CO 60:25.

37 Seymour to Cardwell, No. 33, March 24, 1865, CO 60:21.

38 Report by W.G. Cox, July 1, 1866, enclosed in Birch to Cardwell, No. 52, July 10, 1866, CO 60:25.

39 Douglas to Lytton, No. 40, November 30, 1858, CO 60:1.

40 Douglas to Lytton, No. 127, Financial, April 8, 1859, CO 60:4.

41 Douglas to Lytton, No. 167, June 8, 1859, CO 60:4.

42 Douglas to Stanley, No. 29, July 1, 1858, 7833, CO 60:1.

43 Douglas to Stanley, No. 34, August 19, 1858, CO 60:1.

44 Edmund Hammond, Foreign Office, to Merivale, October 19, 1858, CO 60:2.

45 Douglas to Lytton, No. 30, November 9, 1858, CO 60:1.

46 Murdoch and Rogers, Colonial Land and Emigration Office, to Merivale, February 7, 1860, CO 60:9.

47 Douglas to Newcastle, No. 39, Financial, April 21, 1860, CO 60:7.

48 Douglas to Newcastle, No. 42, April 23, 1860, CO 60:7.

49 Douglas to Newcastle, No. 8, Miscellaneous, January 24, 1860, CO 60:7.

50 Douglas to Newcastle, No. 42, April 23, 1860, CO 60:7.

51 Douglas to Newcastle, Separate, July 6, 1860, CO 60:7.

52 Notes added in the Colonial Office to W. Elmsley to Under-Secretary of State [unnamed], July 21, 1860, CO 60:9, enclosing the original of the petition of May 22, 1860, from Westminster residents to Secretary of State for the Colonies.

53 Douglas to Newcastle, Separate, February 28, 1861, CO 60:10.

54 Newcastle, “British Columbia and Vancouvers Island,” memorandum, March 27, 1863, enclosed in Arthur Helps, Whitehall, to Fortescue, June 12, 1863, CO 60:17.

55 Newcastle, “British Columbia and Vancouvers Island,” memorandum.

56 Douglas to Newcastle, Separate, July 2, 1863, CO 60:15.

57 Helmcken as Speaker of the Legislative Assembly to Douglas, February 9, 1864, in Douglas to Newcastle, No. 3, Legislative, February 12, 1864, CO 305:32.

58 Seymour to Cardwell, No. 56, October 4, 1864, CO 60:19.

59 Murdoch and Rogers, Colonial Land and Emigration Office, to Merivale, February 7, 1860, CO 60:9.

60 Douglas to Newcastle, Separate, April 22, 1861, CO 60:10.

61 Newcastle, “British Columbia and Vancouvers Island,” memorandum.

62 Douglas to Newcastle, Separate, July 2, 1863, CO 60:15.

63 Daily News, February 17, 1849, CO 305:2.

64 Seymour to Cardwell, No. 59, October 7, 1864, CO 60:19.

65 On Haynes see Seymour to Cardwell, Nos. 71 and 72, November 25 and 26, 1864, CO 60:19; on Cox and Gaggin, Seymour to Cardwell, No. 72, November 26, 1864, CO 60:19; also Margaret A. Ormsby, “John Carmichael Haynes,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/haynes_john_carmichael_11E.html.

66 Henry Maynard Ball, police magistrate, to private secretary of Governor James Douglas, Lytton, June 3, 1861, in CO GR 1372, box 1354, file 1344.

67 Petition to Governor James Douglas, Lytton, May 30, 1861, in CO, GR 1372, box 1354, file 1344.

68 Ball’s response and the petition of support described in the following paragraphs are in CO GR 1372, box 1354, file 1344.

69 Petition to Governor James Douglas, Lytton, June 3, 1861, in Colonial Correspondence, GR 1372, box 1354, file 1344.

70 “Henry Maynard Ball (1825–1897),” typescript in BCA, VF.

71 Hester E [Haynes] White, “John Carmichael Haynes,” British Columbia Historical Quarterly 4, 3 (1940): 183.

72 White, “John Carmichael Haynes,” 183.

73 Margaret A. Ormsby, ed., A Pioneer Gentlewoman in British Columbia: The Recollections of Susan Allison (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1976), 167n.

74 White, “John Carmichael Haynes,” 189–90.

75 Conversation of Hamilton Laing with Allan Brooks, recounted by Allan Brooks to Jean Barman, Black Creek, February 23, 1993; Robert M. Hayes, “Pioneer Judge Had Three Families,” Kelowna Daily Courier, January 8, 1997.

76 Mourning Dove, Mourning Dove: A Salishan Autobiography (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2021), among other editions.

77 Hum-ishu-ma, “Mourning Dove,” in Cogewea, the Half-Blood: A Depiction of the Great Montana Cattle Range (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1981), vii; also Ormsby, “John Carmichael Haynes,” which ignores this relationship altogether.

78 George J. Fraser, The Story of Osoyoos, September 1811 to December 1952 (Penticton: Penticton Herald, 1952), 77; White, “John Carmichael Haynes,” 198.

79 White, “John Carmichael Haynes,” 198.

80 Fraser, The Story of Osoyoos, 78.

81 Sue Dahlo, “William Cox: Gold Commissioner,” Boundary Historical Society, Report 13 (1995), 31–33; Mrs. W.G. Cox to Governor Seymour, November 5, 1868, and W.A.G. Young to Mrs. W.G. Cox, January 4, 1869, cited in Margaret A. Ormsby, “Some Irish Figures in Colonial Days,” British Columbia Historical Quarterly 14, 1–2 (1950): 75.

82 Unsigned letter to W.G. Cox, September 21, 1860, reproduced in Ormsby, “Some Irish Figures in Colonial Days,” 68.

83 Dorothy Blakey Smith, ed., The Reminiscences of Doctor John Sebastian Helmcken (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1975), 234. On Cox, see also G.R. Newell, “William George Cox,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cox_william_george_10E.html.

84 Quoted in Dorothy Blakey Smith, “John Boles Gaggin,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gaggin_john_boles_9E.html.

85 May 20, 1862, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1862: 50; also Ormsby, “Some Irish Figures in Colonial Days,” 63, 69. Humphreys’s and Lucy’s story is told in depth in Jean Barman, Invisible Generations: Living between Indigenous and White in the Fraser Valley (Halfmoon Bay, BC: Caitlin Press, 2019).

86 Ormsby, “Some Irish Figures in Colonial Days,” 69; also Michael F.H. Halleran, “Thomas Basil Humphreys,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/humphreys_thomas_basil_11E.html.

87 Douglas to Newcastle, No. 11, February 3, 1863, CO 60:15.

88 Douglas to Newcastle, No. 11, February 3, 1863, CO 60:15.

89 Douglas to Newcastle, Separate, November 13, 1863, CO 60:16.

90 Seymour to Cardwell, Separate, May 18, 1865, CO 60:21.

91 Douglas to Lytton, No. 167, June 8, 1859, CO 60:4.

92 Douglas to Newcastle, No. 42, April 23, 1860, CO 60:7.

93 July 16, 1861, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861: 112.

94 July 30, 1861, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861: 114.

95 April 4, 1861, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861: 37.

96 Kennedy to Cardwell, No. 48, Separate, June 26, 1866, CO 305:28.

97 Seymour to Buckingham, Private, June 26, 1867, CO 60:28.

98 Matthew Begbie to Thomas Begbie, July 8, 1867, CO 60:31.

99 Granville George Leveson-Gower, 2nd Earl Granville, secretary of state for the colonies, to Seymour, No. 3, December, 29, 1868, NAC RG7:G8C/15.