Chapter 7: Crediting Indigenous Women

The tendency during the early years of non-Indigenous men’s presence in the future British Columbia to view Indigenous women as lesser persons than their non-Indigenous counterparts was widespread at the time and would long continue to be so. The notion is so engrained, both in everyday life and in the dominant historiography, as needing to be excised not once, but time and again.

Even as Indigenous women could be, and all too often were, stereotyped by virtue of their racial descent and set upon by non-Indigenous men as objects of sexual desire, something else was also happening during the critical quarter century between 1846, when the land base of today’s British Columbia was awarded to Britain, and 1871, when that land base became the west coast province of British Columbia.

Indigenous women had their own reasons for accommodating, when they chose to do so, the newcomer men’s sexual desires—those reasons, while difficult to intuit given the paucity of first-hand accounts from women’s perspectives, are not impossible to imagine. The time is long past when we might deny Indigenous women being determined, tough, and rational persons with minds of their own, who lived in sometimes impossible circumstances during those years when British Columbia hung in the balance.

Indigenous women during the fur trade

The presence of Indigenous women in the lives of non-Indigenous men long preceded the gold rush, being an everyday aspect of the fur trade of the early nineteenth century, which almost inevitably legitimized at least some of their gold-mining successors acting similarly. Prior to Vancouver Island coming into existence as a British possession in 1849, such relationships were commonplace. James Douglas, long before he became governor of the colony of Vancouver Island, had partnered with the daughter of the fur trader in charge of his first Hudson’s Bay Company posting in the Cariboo and of a woman of Cree and French Canadian descent. Despite their wedding in a Christian ceremony as soon as it was possible to do so, unions cutting across white assumptions of acceptability would long be suspect, to some extent continuing to be so into the present day.

Vancouver Island’s being made a British colony in 1849 under the aegis of the Colonial Office masked but did not hide its fur trade ambience. Numerous of the men who had a family with an Indigenous woman, or a woman of Indigenous descent, took advantage of the opportunity Vancouver Island gave them to settle down.

Examples abound of men come west with the fur trade who did so. William Henry McNeill and John Lemon are among those recorded as holding twenty or more acres of land on Vancouver Island, with Frederique Minie and Louis Trudelle among those purchasing town lots in Victoria.

Born in Boston in 1801, William Henry McNeill early on commanded vessels along the Pacific coast on behalf of the Hudson’s Bay Company. In about 1831 he partnered with Matilda, a chief’s daughter who Vancouver Island medical doctor John Sebastian Helmcken recalled as “a very large handsome Kijani woman, with all the dignity and carriage of a chieftainess,” which she was, the Kijani being a division of the Haida-language group.1 The McNeills had nine children together before Matilda, according to Helmcken writing at the end of 1850, “died just before her confinement, attended by Indian women from hemorrhage after twins had been born.”2 In 1866 McNeill turned to a Nass woman named Martha by whom he had no children.3 McNeill appears to have had divided loyalties, being among the signatories on an 1869 petition to the American president supporting the annexation of British Columbia to the United States.4

Born in about 1815 in rural Quebec, John Lemon joined the HBC in 1833 to be employed variously across the Pacific Northwest. While at Fort McLoughlin on the British Columbia north coast, he lived with a Bella Bella woman. Transferred to Fort Victoria, he and a Saanich woman named Sarah had six children together between 1849 and 1866.5 Disposing of his Victoria holding, in 1861 Lemon moved his family to Cowichan Bay, where he ran the Cowichan Hotel until his death in 1883.6

Born in about 1817 in rural Quebec, Frederique Minie joined the HBC in 1838, to spend a decade between Fort Taku and Fort Stikine in the Alaskan panhandle before being dispatched to Fort Victoria. Between 1853 and 1861 he had four children by a woman described in Catholic Church records as Marguerite Maurice of the “Bibalets” tribe. He then wed Marie Maurice or Morris, identified as a “half breed,” “by whom he had two more children.”7

Born in 1821 in Montreal, Louis Trudelle joined the HBC in 1839 to spend the next eight years on the north coast before being posted in 1851 to Victoria, where he purchased land, soon to decide he preferred Saanich. There he wed a local woman named Julie, who died soon after their first child was born, whereupon he opted for a Cowichan woman named Marie. With Marie or with another woman he had two more children.8

Absence of white women

As these examples suggest, white women were a rarity during the British Columbia fur trade and the gold rushes beginning in 1858.9 Both its distant location and the nature of mining kept away all but a few. Even the handful of “female emigrants” recruited from England in the early 1860s to serve as maids for the handful of white wives in Victoria were possibly lured away, as when a gold miner offered one of them “2000$ to buy her wedding attire.”10 It is not without reason the two economies have been similarly framed historically as male activities. They were.

Indicative was the experience of thirty-year-old Englishman Robert Burnaby, who we met in Chapter 6. Not long after arriving in Victoria at the beginning of 1859, he described in a letter to his older brother back home a ball he attended where “the proportion of ladies to gentlemen was as plums to flour in a workhouse pudding, consequently the Naval and Military men [stationed nearby] had things all their own way.” Not only that, but “the majority of the belles are belles sauvages, and you can detect in their black eyes, high cheek bones, and flattened head whence they came.”11 The reference was most likely to their being offspring of HBC personnel and women of Indigenous descent.

The absence of white women was noted and lamented. Governor James Douglas explained to the Colonial Office in October 1859, a year into the gold rush, how “the entire white population of British Columbia does not probably exceed 5,000 men, there being, with the exception of a few white families, neither wives nor children to refine and soften, by their presence, the dreariness and asperity of existence.”12 Even in Victoria numbers were small, an early resident describing as of 1860 “a female” as “a rare object in those days, when women and children were as scarce as hen’s teeth and were hardly ever met on the streets.”13

An internal memo of February 1860 from the British Emigration Office in London to the Colonial Office, based on information received from Douglas, underlines the full extent to which white women were absent, even more so in the mainland colony of British Columbia: “Miners between Forts Hope & Yale are said to be 600, between Yale & the Fountain 800 and about Alexandria and Quesnel River 1000, making in all 2400…The White population of the Colony amounts to 5000 Men, with scarcely any Women or Children.”14 Writing shortly thereafter, the well-travelled Judge Begbie put “the number of Whites in the Colony in July 1860” at three thousand, of whom not more than half was a fixed population, with few women or children.15

Indigenous women coming into view

Given newcomer men were, except in rare instances, without a woman of their own kind, so to speak, Indigenous women were even more visible than might otherwise have been the case. The ambivalence of the unwed Bishop Hills, then in his mid-forties, as recorded in his private journal intended for his eyes only, was almost certainly not unlike that of many others. As early as the spring of 1860 Hills could not help but be impressed by how “the young women begin to dress themselves in fashionable attire,” taking special note of one who “was washing her face & really looked pleasing with black sparkling eyes & rosy cheeks.”16 On the other hand, visiting Victoria’s “Chympsian [Tsimshian] Village” five days later, Hills did a double take on coming across “two Indian women dressed I may almost say in the latest fashion! Round straw hats with flowing ribbons, & hooped dresses! However, an adornment of their peculiar kind in the shape of red paint purposely daubed upon their faces.”17

It was not only in Victoria where Indigenous women stood out. On a road trip in July 1860, Hills took note of “two females, very plain young women,” riding “as men” into where he and others were camping. “Their dresses were gay—European manufacture—bright colours” and “their horses tore away in like style.”18 Come December 1860 Hills described in his journal how when he entered “an Indian abode,” he took note how in the women “there is a grace, a softness of voice, a truly feminine submission, and sometimes even beauty.”19

It was a fine line for Hills in composing his daily journal entries between being admiring of the women he encountered and lamenting the sharp gender differential and the lack of self-control among white males. Over time Hills became more critical, consequent perhaps on his being caught up in stories respecting white men’s intrusion on Indigenous women’s bodies. Writing from Cayuse on June 10, 1861, Hills was beside himself:

"The immorality of the whites is almost universal. The poor Indian girls & mothers are all used by them for the worst purposes. They live with these women in the most open manner & put them away for others as their fancy dictates. They can purchase them off their friends. One man makes no secret of having given a large price for his Indian woman—the sum named is $600 £120, but this probably is above the mark. I am glad to say this man is not an Englishman but a Southern American.20

"

Such descriptions were common in Hills’s journal. March 13, 1862, “two Xtian Indians” arrived from Fort Simpson explained to Hills how “their friends have come principally for the purposes of Prostitution.” Going to see them, Hills described in his journal what he encountered: “There was much drunkenness going on. Two or three women in particular were in a state of helpless intoxication. Others were busy making up gay dresses.”21

Indigenous women as objects of sexual desire

The perception of Indigenous women as accessible for sexual purposes, either of their own volition or as persuaded by others, was linked in the non-Indigenous thinking of the day—indeed into the present day—to Indigenous women’s long-time characterization as inferior beings intended to service men at their convenience. Viewing Indigenous women in this way validated men’s behaving as they would without the women’s consent. In the phrase still in use, “she made me do it.”

Even among those in charge the language was commonplace, as when British Columbia governor Frederick Seymour described to the Colonial Office in May 1865 how the populations of three towns in the Cariboo, then the centre of a gold rush, “were dressed in flags, and the population turned out into the Streets for it was announced that several sleighs loaded with [derogatory term for Indigenous women] were on the road.”22 Indicative of the perception was a Colonial Office minute tempering an 1851 request from Vancouver Island governor Richard Blanshard to dispatch a garrison of British troops to protect “British subjects” from Indigenous peoples by pointing out how “it is not very uncommon for the Europeans…to be the aggressors by insulting the women of the natives.”23

The reality was often in plain view. The summer of 1860 witnessed a seasonal migration of “Indian Tribes” numbering upward of four thousand, double the white population, into “the outskirts of the Town of Victoria for the purpose,” according to Douglas, of “selling their Furs and other commodities.”24 Douglas thereupon requested as a “moral restraint” a naval vessel, based at nearby Esquimalt, be stationed at the entrance to Victoria harbour, whose officer in charge differently asserted that the Indigenous peoples’ “principal object in coming here, from what I can collect is the fearfully demoralizing one of trading with the unchastity of the [derogatory term for Indigenous women].”25

Indigenous women’s sexuality very often trumped other considerations respecting them. Anglican missionary teacher Alexander Garrett was in April 1861 beseeched by “a number of Indians,” in Bishop Hills’s words, “to free them from the violence of three sailors in one of the Men of War,” who “had taken possession of an Indian lodge & were drinking & abusing the poor Indian women.” Garrett did so, only to have one of the sailors return the next day with a question: “Can you tell me, says the Sailor, whereabouts is the part of the Camp where I was yesterday?” Not long after, Garrett and his pupils “overheard a quarrel between a drunken Sailor & an Indian woman…abusing him for not paying her the wages in iniquity.”26

Within this way of thinking, white men’s actions toward Indigenous women could have unexpected consequences, as when Chilcotins in May 1864 killed fourteen white men constructing a wagon road from Bute Inlet to the Cariboo, whom they perceived as interfering with their women on their territory. As explained to the Colonial Office by Vancouver Island governor Arthur Kennedy:

"It is known that the Chillcoaten [sic] Tribe are peculiarly jealous of their women and…I would fear that the residence of a number of single white men among the Chilcoatens, and the almost certain results, may be among the causes which have led to the catastrophe.27

"

It was not that Kennedy was himself particularly protective of Indigenous women, asserting to the Colonial Office two months later: “The condition of the Indian population is very lamentable. Drunkenness and prostitution being the prevailing and prominent characteristics.”28

Two months later Kennedy sought to counter what he now termed “the degraded and drunken habits of the Indians,” not by remediation but by separation:

"The present Indian Settlement at Victoria is a disgrace to humanity, and I cannot learn that any effective measures have been taken to prevent the shameless prostitution of women and drunkenness of the men who live mainly by their prostitution. The Indians must be removed from this locality.29

"

In February 1866 Kennedy lamented “prostitution unchecked,” which he backed up with letters from the head of the Indian Mission and from Philip Hankin, the superintendent of police. By Hankin’s count:

"There are about 200 Indian prostitutes living in Cormorant, Fisgard, and Store Streets in a state of filth, and dirt beyond all description. On entering one of their shanties in the afternoon I have seen 3 or 4 Indian women lying drunk on the floor, nearly naked, covered with blood, and their faces cut with broken bottles with which they had been fighting.

In one place known as the “Gully” between Johnson and Cormorant Streets some of these dens of infamy are two and three stories high, the rooms about eight feet square, and as many as 6 or 8 persons living in each room…

The shanties are principally owned by Chinese, and hired by the Indians at a monthly rental of about 5 dollars…Whiskey sellers, prostitutes and bad characters are to be found in this locality, and unfortunate sailors coming on leave from their ships are allured here by the Indian women, and robbed.

If it were not for the constant supervision of the Police, it would be dangerous for any respectable person to walk through these streets either by day or night. New shanties have lately been erected, and are still increasing in number.30

"

It became a matter of course for officials to demean Indigenous women out of hand without any consideration of newcomer men’s roles in the course of events. British Columbia’s commissioner of lands and works and surveyor general, Joseph Trutch, asserted in early 1870, in a more general report respecting Vancouver Island’s Indigenous population, how “prostitution is another acknowledged evil prevailing to an almost unlimited extent among the Indian women in the neighbourhood of Victoria.”31

Indigenous women used and abused

Many Indigenous women’s lives were not pretty. Bishop Hills was repeatedly caught up in cases where they were being used and abused. In the single month of January 1862 in Victoria, he documented five such cases in his journal:

On January 1 he recorded how the wife of “a young man of the Hydah tribe” who “is a Chiefs son,” was “led away & is now a Common Prostitute in the town.”32

On January 19 Hills was beseeched by “an Indian in trouble because his wife had been taken from him by an American,” but “on further inquiry it appeared the man was not unwilling to give up his wife if the seducer would give him a good price.” It turned out “he wanted 200 Dollars & said a Mexican usually buy the women at such prices.”33

Later in the same day Hills was asked “to obtain the assistance of Police to fetch back the wife of a young man” associated with the Anglican school Hills oversaw, “who had been abducted by an American.”34

On January 25 Hills sought to resolve, to no avail, the case of an orphaned Indigenous girl who had run away from a couple who had “endeavoured to force her to prostitute herself,” only to have them convince the police to retrieve her. “Afterwards her masters were seen kicking & chasing her down the street.”35

At the end of the month Hills visited “the Indian Villages,” home to groups of Songhees, Fort Rupert, and Haida people in the common Indigenous practice of spending time in Victoria. The Songhees and Fort Rupert villages passed muster from his perspective, but not the Haida village, so Hill evoked in his daily journal: “We visited the Hydah Village also had a talk with various members of it. There is a boldness & impudence increasingly manifested. The men live upon the iniquitous gains of their wives, daughters, sisters & slaves.”36

The situation was not limited to Victoria. While taking a walk in June 1862 near where Hills and two others were camping at Boston Bar, he had a similar experience:

"During a stroll from the camp an Indian in wild & disheveled excitement came running through the bushes breathless. He said a man had seized his daughter a young girl & was carrying her off. He had knocked down the mother & threatened to kill her. I soon after met one of my own people who confirmed the account & said the man had refused to listen to their remonstrances. We started in pursuit but could no where discover the party we were in quest of. Such outrages I regret to say are not infrequent. I have had complaints frequently from husbands & fathers of the forcible abduction of their wives & children by the white savage. In the present case the man was either a Frenchman or a Mexican.37

"

So it went time and again.

The dance houses phenomenon

No aspect of the gold rush would be more difficult, even for the zealous Bishop Hills, to eradicate or at the least to moderate than were dance houses. His attention had already turned to them by the end of 1861, as he wrote in his journal on December 22:

"There has lately been opened on a large scale a place of resort called a Dance House. There are two others I understand in the Town. The object of these is to gather together poor Indian women for association with the lower sort of whites. I wrote yesterday to the Chief Commissioner of Police on the subject, expressing the feelings of the Clergy. I was told to day that in America they were not allowed. Sad indeed if in a British colony evils of this kind should be greater than in a country not noted for its purity.38

"

By the end of January 1862, Hills was becoming even more open in his journal respecting Indigenous women and, more specifically, concerning the purpose and character of dance houses. As noted above, Hills found the situation in the Haida village near Victoria particularly problematic:

"The men live upon the iniquitous gains of their wives, daughters, sisters & slaves. The dance houses which are open every night are great inventories to this kind of wickedness…Dance houses are opened in the Town [Victoria] for the purpose of attracting Indian women. We saw frequent instances of the abduction of wives & children of Indians by dissolute white men & lately several distressing witnesses have come to my notice. They should be protected by which a prohibition shd be put to such places. The various tribes need a wise & fine mediator assured with coercive power when necessary. The Indian is like a child & must be treated with kindness yet with firmness.39

"

The next day, visiting “the lodges of the Chmseans [Tsimshian] and Stickeens,” Hills came upon “a woman making up a dress” for “the dance house tonight” and lamented in his journal: “Poor creatures they know these things are wrong—but the temptations are too strong. Alas that white men should be the tempters.”40 Hills was almost certainly aware, but conveniently forgot to make visible in his journal, that it was common knowledge dance halls were not only patronized by, but also operated by, white men as profit-making ventures.

The challenge of being perceived as Indigenous

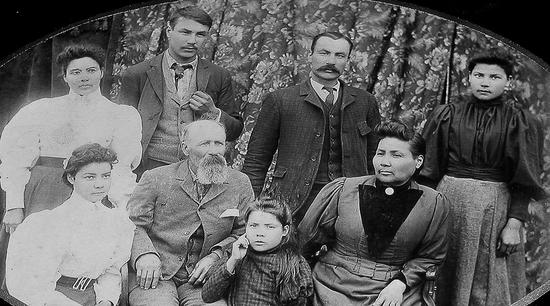

That white women were in very short supply in colonial British Columbia did not make those who were present any less willing to diminish Indigenous women and their daughters, including those making their way in polite society, such as it was, in a British Columbia in the making. The latter were ever susceptible to being criticized and demeaned, if not to their faces then behind their backs. Such was the case even with James Douglas’s five daughters born between 1834 and 1854, who were, in the language of the day, “quarter-breeds” by virtue of their Indigenous maternal grandmother, to which must be added the additional burden of their father’s part-Black descent. On the other hand, they were the governor’s daughters at a time when even part-white women of any background were desirable by virtue of having some white descent. Douglas was for his part keen to introduce them to desirable unwed men he could envisage as suitable sons-in-law. So it was that when unwed Anglican bishop George Hills arrived in January 1860, he had been in Victoria only a few short months when “he received a note from the Governor asking me to join himself” for a morning ride including, among others, “the two Miss Douglas’s.”41

When Douglas’s eldest daughter married, it was not her father’s, but rather the couple’s doing. John Sebastian Helmcken, a medically trained HBC clerk in his mid-twenties, arrived from London in 1850 and was instantly smitten by Douglas’s eldest daughter, Cecilia, whom he described in his memoir:

"I saw Mr. Douglas—he did not impress me very favourably, being of very grave disposition with an air of dignity—cold and unimpassioned…At the windows stood a number of young ladies, hidden behind the curtains, looking at the late important arrivals, for visitors were very scarce here, but we were not introduced. Anyhow before going away, the room of Mr. Douglas, partly an office and partly domestic, stood open, and there I saw Cecilia, his eldest daughter flitting about, active as a little squirrel, and one of the prettiest objects I had ever seen, rather short but with a very pretty graceful figure—of dark complexion and lovely black eyes—petite and nice…I was more or less captivated.42

"

Back in Victoria after a stint in Fort Rupert, Helmcken wrote, “I spent much of my time courting…The courtship was a very simple affair—generally in the evening, when we had chocolate and singing and what not—early hours kept.”43 Then came Helmcken’s next task, set for him by his prospective father-in-law: “I had to build a house. Mr. Douglas gave me a piece of land, an acre, wanted me to build on it, because being close together there would be mutual aid in case of trouble…It pleased Cecilia—she was near her mother and relatives—no small comfort to her in my absence.”44 They wed on December 27, 1852, and went on to have four sons and three daughters.45

Of the other daughters, Jane wed Alexander Dallas, who was her father’s successor with the HBC; Agnes wed Arthur Bushby, recruited from England to assist British Columbia Chief Justice Matthew Baillie Begbie; Alice wed Charles Good, a minister’s son; and the youngest daughter, Martha, who would in 1901 publish History and Folklore of the Cowichan Indians, married Victoria civil engineer Dennis Harris.46

That the Douglas daughters wed white men does not mean they were free from being talked about and diminished based on their Indigenous descent. Sophia Cracroft, whom we met in Chapter 5, visited Victoria in the spring of 1861 and described Governor Douglas’s wife, Amelia, in a letter home as “a half caste Indian,” and their twenty-two-year-old daughter, Jane, as of “the Indian type,” even though “two generations removed from it,” given “the great width & flatness of the face…& even her intonation & voice are characteristic (as we now perceive) of her descent.”47

Returning a decade later, Cracroft had not one bit changed her mind respecting the physical appearance of Amelia Douglas and her family:

"I dare say you may not remember that she was a half caste Indian very shy, awkward, & retiring as much into the background as she can possibly do…She was very cordial…we saw only her grand daughter…who has as much of the Indian features & colouring as her grandmother.48

"

Attitudes even toward otherwise respectable women and their descendants were firmly set in place, as they would long remain.

This white woman’s perspective distinguishing persons with Indigenous descent as alien to the way things ought to be would be repeated time and again, almost as a matter of course, by both white women and white men. A well-connected English naval officer who arrived in 1862 to command a Royal Navy gunboat based at Esquimalt near Victoria was vituperative in a letter headed “Private Not to be copied” that he wrote to his well-connected father respecting the “ignorance and barbarism” of James Douglas’s family by virtue of “Mrs. Douglas being a half-breed, and her daughter quarter-breeds.” Then in his mid-twenties, Edmund Hope Verney described Douglas’s wife as “a good creature, but utterly ignorant: she has no language, but jabbers french or english or Indian, as she is half Indian.” Douglas’s eldest daughter, Cecilia, was “a fine [derogatory term for Indigenous woman]” and his youngest Martha “perhaps the best of the lot: she is a fat s——, but without any pretence to being anything else.”49 Given the “ignorance and barbarism” of Douglas’s family, “a refined English gentleman is sadly wanted at the head of affairs.”50 The gulf could not have been greater between the reality of everyday life in British Columbia at the time and elite English assumptions respecting the way they ought as a matter of course to be.

Consequences

Alongside the visible consequences of diminishing Indigenous woman and their male partners, be they white or Indigenous, are the consequences ranging from attitudes to actions for successive generations into the present day. Indigenous women and their offspring by non-Indigenous men were not only encouraged but legally caused to disappear from view with consequences for descendants and historians alike into the present day. In 1868 the Colonial Office queried Vancouver Island governor Frederick Seymour respecting the establishment of a registry of births, marriages, and deaths. As to his reason for responding in the negative: “The Majority are Indians whom we could hardly expect to register any one of the three great events of life. Many of the white men are living in a state of concubinage with Indian women far in the Interior. They would hardly come forward to register the birth of some half breed bastard.”51

Not unexpectedly, neither the total numbers of Indigenous people in the future British Columbia, nor the numbers of Indigenous women partnering at least in the moment with non-Indigenous men, are possible to determine in their entirety. In 1861 James Douglas undertook “a census of the Native Tribes” which counted “25,873 souls” on Vancouver Island, with another eight thousand on “the continental coast of America, immediately opposite Vancouver’s Island.”52

A close reading of contemporary primary and secondary sources, including church and census records, turned up in British Columbia between the beginning of the gold rush in 1858 and 1871, the year it joined Canada, 625 documented unions between named non-Indigenous men and sometimes named Indigenous women. These unions can be variously parsed, but however it be done, the bottom line is that Indigenous women mattered to the future of British Columbia. They not only mattered, they mattered a lot. Just as with gold miners, except for Indigenous women by their actions persuading newcomer men to stay longer, in many cases for a lifetime, there might well have been no British Columbia in the form we know it today.

1 Dorothy Blakey Smith, ed., The Reminiscences of Doctor John Sebastian Helmcken (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1975), 108; Derek Pethick, S.S. Beaver: The Ship That Saved the West (Vancouver: Mitchell Press, 1970), 48, fn3.

2 Smith, Reminiscences of Doctor John Sebastian Helmcken, 108.

3 G.R. Newell, “William Henry McNeill,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcneill_william_henry_10E.html.

4 Willard E. Ireland, “The Annexation Petition of 1869,” British Columbia Historical Quarterly 4, 4 (October 1940): 267–87.

5 Church records, St. Andrew’s Catholic Church, Victoria, 1849–1934, in BC Archives, Add. Ms. 1.

6 Bruce McIntyre Watson, Lives Lived West of the Divide: A Biographical Dictionary of Fur Traders Working West of the Rockies, 1793–1858 (Kelowna, BC: University of British Columbia Okanagan, 2010), 608–9.

7 Church records, St. Andrew’s Catholic Church, Victoria, 1849–1934, in BCA, Add. Ms. 1.

8 Watson, Lives Lived West of the Divide, 941.

9 For an exception, see Jean Barman, Constance Lindsay Skinner: Writing on the Frontier (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002).

10 January 13–15, 1863, entries in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1863: 5–6, typescript in Anglican Church, Ecclesiastical Province of British Columbia, Archives.

11 Robert Burnaby to Tom Burnaby, February 22, 1859, in Anne Burnaby McLeod and Pixie McGeachie, Land of Promise: Robert Burnaby’s Letters from Colonial British Columbia (Burnaby, BC: City of Burnaby, 2002), 65.

12 Douglas to Newcastle, No. 224, October 18, 1859, CO 60:5.

13 Edgar Fawcett, Some Reminiscences of Old Victoria (Toronto: Walter Briggs, 1912), 264.

14 Murdoch and Rogers, Colonial Land and Emigration Office, to Merivale, February 7, 1860, CO 60:9.

15 Minute by CF [Fortescue], December 15, 1860, on Douglas to Newcastle, No. 58, June 22, 1860, CO 60:7.

16 April 23, 1860, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1860: 123.

17 April 28, 1860, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1860: 25.

18 July 5, 1860, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1860: 153.

19 November 23, 1860, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1860: 266.

20 June 10, 1861, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861: 73.

21 March 13, 1862, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861–62: 24.

22 Seymour to Cardwell, No. 38, May 2, 1865, CO 60:21.

23 Minute by G [Grey], November 12, 1851, on Richard Blanshard, governor of Vancouver Island, to Earl Grey, August 11, 1851, CO 305:3.

24 Douglas to Newcastle, No. 39, August 8, 1860, CO 305:14.

25 R. Lambert Baynes, Rear Admiral, to Douglas, August 1, 1860, in Douglas to Newcastle, No. 39, August 8, 1850, CO 305:14.

26 June 10, 1861, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861: 44–46.

27 Kennedy to Newcastle, Separate, May 13, 1864, CO 305:22.

28 Kennedy to Newcastle, No. 40, Separate, July 7, 1864, CO 305:22.

29 Kennedy to Cardwell, No. 80, Miscellaneous, October 1, 1864, CO 305:23.

30 Philip Hankin, Superintendent of Police, to Kennedy, February 8, 1866, enclosed in Kennedy to Cardwell, No. 10, Financial, February 13, 1866, CO 305:28.

31 Joseph W. Trutch, “Memorandum,” January 13, 1870, enclosed in Musgrave to Granville, No. 8, January 29, 1870, CO 60:38.

32 January 1, 1862, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861–62: 31.

33 January 19, 1862, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861–62: 5.

34 January 19, 1862, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861–62: 5.

35 January 25, 1862, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861–62: 8–9.

36 January 31, 1862, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861–62: 10–11.

37 June 25, 1862, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861–62: 70.

38 December 22, 1861, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861–62: 166–67.

39 January 31, 1862, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861–62: 10–11.

40 February 1, 1862, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1861–62: 11.

41 April 26, 1860, entry in “The Journal of George Hills,” 1860: 75.

42 Smith, Reminiscences of Doctor John Sebastian Helmcken, 81.

43 Smith, Reminiscences of Doctor John Sebastian Helmcken, 120.

44 Smith, Reminiscences of Doctor John Sebastian Helmcken, 127.

45 Daniel P. Marshall, “John Sebastian Helmcken,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/helmcken_john_sebastian_14E.html.

46 Martha Douglas Harris, History and Folklore of the Cowichan Indians (Victoria: Colonist Printing and Publishing Company, 1901).

47 Sophia Cracroft, February 25, 1861, in letter reproduced in Dorothy Blakey Smith, ed., Lady Franklin Visits the Pacific Northwest: Being Extracts from the Letters of Miss Sophia Cracroft, Sir John Franklin’s Niece, February to April 1861 and April to July 1870 (Victoria, BC: Provincial Archives of British Columbia, 1974), 12–13.

48 Sophia Cracroft, April 30, 1870, in Smith, Lady Franklin Visits the Pacific Northwest, 118.

49 Edmund Hope Verney to Sir Henry Verney, July 20, 1862, in Allan Pritchard, ed., Vancouver Island Letters of Edmund Hope Verney, 1862–65 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1996), 74–75.

50 E.H. Verney to Sir H. Verney, August 16, 1862, in Pritchard, Vancouver Island Letters of Edmund Hope Verney, 1862–65, 84.

51 Seymour to Buckingham, No. 100, August 11, 1858, CO 60:33.

52 Douglas to Labouchere, No. 24, October 20, 1856, 11582, CO 305:7.