Chapter 2: The Year That Changed Everything (1858)

James Douglas’s governorship of Vancouver Island, following its acquisition by Britain in 1846, was one thing; to be landed with a gold rush on the mainland thirty times that island’s size was a wholly different matter.1 That Douglas, overseen by the Colonial Office in faraway London, managed the feat during 1858, the year that changed everything, is remarkable.

Enter the 1858 gold rush

As 1858 came into view, so did the possibility of a gold rush.2 Unlike Vancouver Island, over which the fur-trading Hudson’s Bay Company had requested and received a ten-year lease extending to May 1859, the mainland of today’s British Columbia was, except for a handful of HBC trading posts, an Indigenous place.3

In a letter of March 22, 1858, to the Hudson’s Bay Company that was shared with the Colonial Office, James Douglas previewed what might ensue. Having experienced the gold rush in small doses, he envisaged the arrival on the largely unknown mainland of “a great number of Americans,” some of them veterans of the California gold rush where miners had had ongoing confrontations with civil authority.

Douglas offered to do what was wanted: “I should be glad to keep these parties out of the British Territory, and would undertake with a very moderate force to accomplish that object, as the avenues to the country are few, and might be easily guarded.” He had already “written to Her Majesty’s Government on the subject and shall not fail to communicate with you as soon as I receive their reply.” Three days later Douglas followed up with the HBC once he had been informed by “an experienced miner” that “the bedrock and other geological features” of “the principal diggings” on the banks of the Fraser River “are all characteristics of the gold Districts of California and other countries.”4

Indigenous miners initially in charge

Indigenous people had been a priority for Douglas during his many years in the fur trade and continued to be so. Writing shortly thereafter to the secretary of state for the colonies, Henry Labouchere, Douglas described “the search for gold” as being “carried on almost exclusively by the native Indian population, who have discovered the productive beds, and put out almost all the gold, about eight hundred ounces, which has been hitherto exported from the country; and who are moreover extremely jealous of the whites and strongly opposed to their digging the soil for gold.” Douglas explained how “the few white men who passed the winter at the diggings, chiefly retired Servants [employees] of the Hudson’s Bay Company, though well acquainted with Indian character, were obstructed by the natives,…who having, by that means, obtained possession of the spot, then proceeded to reap the fruits of their labors.” Douglas considered it “worthy of remark and a circumstance highly honorable to the character of these [Indigenous people] that they have on all occasions scrupulously respected the persons and property of the white visitors, at the same time that they have expressed a determination to reserve the gold for their own benefit.”5

As the search for gold expanded, Douglas’s sense of obligation to the Indigenous population vied with his sympathy for growing numbers of newcomers unaware of what might befall them.6 Hopes for “a second California or Australia” were, he wrote to the Colonial Office in May, being “sustained by the false and exaggerated statements of steamboat operators, and other interested parties, who benefit by the current of emigration, which is now setting strongly toward this quarter.”7 Douglas’s task was to persuade the Colonial Office that the mainland existed and that, with or without a gold rush, it mattered.

Non-Indigenous gold miners’ arrival at Victoria

In what would be the first of numerous such occurrences, Douglas reported from Victoria how on April 25, 1858, “the American Steamer ‘Commodore’ arrived in this Port, direct from San Francisco with 450 passengers on board, the chief part of whom were gold miners,” who “have since left in boats and canoes for Frasers River.” Douglas counted among them about sixty British subjects, with an equal number of native-born Americans, the rest being chiefly Germans, with a small proportion of Frenchmen and Italians.8 Throughout the next months the story would be much the same: “Crowds of people coming in from all quarters. The American Steamer ‘Commodore’ arrived on the 13th of Instant [June] with 450 passengers and the Steamer ‘Panama’ came in yesterday from the same Port with 740 passengers, and other vessels are reported to be on the way.”9

Black arrivals from California

Indicative of the gold rush’s many understories, Douglas did not mention to the Colonial Office then or subsequently, it seems, the inclusion among the passengers who arrived April 25, 1858, on the Commodore of sixty-five free Black people, one of whom had negotiated with Douglas in advance to ensure their equitable treatment should they leave California. Slavery had been abolished in British colonies in 1834, whereas the United States was characterized by a mixture of slave and free states and territories prior to the abolition of slavery in 1865 consequent on the American Civil War. The arrivals had every reason to fear for their future, given the United States Supreme Court had a year earlier denied citizenship both to enslaved Black people and to their descendants.

The April arrivals would be the nucleus of the arrival of several hundred free Black people, many with their families, who crossed the border to make their homes in Victoria and elsewhere on Vancouver Island and nearby islands.10 Douglas would keep an eye on their well-being, noting approvingly at the beginning of 1861 how “a Volunteer Rifle Corps has been formed amongst the coloured population, which I have fostered to the best of my ability” given the lack of any other means for Vancouver Island to defend itself if need be.11

Douglas’s May 8, 1858, query to the Colonial Office

By the beginning of May 1858, James Douglas realized he was in need of advice respecting the growing numbers of gold rush arrivals and so informed the Colonial Office. With the exception of the Black arrivals, Douglas had expected to find the newcomers, based on how they had been described to him by others, as “being, with some exceptions, a specimen of the worst of the population of San Francisco; the very dregs, in fact, of society,” but he repeatedly came in for a surprise. Despite there being in Victoria “a temporary scarcity of food, and dearth of house accommodations; the Police few in number; and many temptations to excess in the way of drink, yet quiet and order prevailed, and there was not a single committal for rioting, drunkenness or other offenses, during their stay here,” which was only as long as it took for arrivals to find transportation from Victoria across the water to the gold fields.12

In his May 8 letter to the Colonial Office, Douglas described how “boats, canoes, and every species of small craft, are continually employed in pouring their cargoes of human beings into Fraser’s River” on the way to gold fields along the river. Envisaging these persons’ possible fates, Douglas reflected on “canoes having been dashed to pieces and their cargoes swept away by the impetuous stream, while of the ill fated adventurers who accompanied them, many have been swept into eternity.”

Putting on his hat as governor of Vancouver Island, Douglas described how “the merchants and other business classes of Victoria are rejoicing at the advent of so large a body of people in the Colony.” These residents became, and would continue to be, along with the nearby port of Esquimalt, which was already being used by the Royal Navy as a base for minding the Pacific, the immediate beneficiaries of the unexpected turn of events.

Douglas came to realize more generally that, because he had no authority over the mainland, nor did anyone else in a formal sense, he needed guidance so as to act as best he could with respect to an escalating situation. In his May 8 letter, Douglas queried his Colonial Office superiors at length respecting the management of a gold rush that was officially none of his business. Who among the arrivals belonged? Who should be encouraged to stay? What about the ever-present American factor? What to do?

"If the country be thrown open to indiscriminate immigration the interests of the [British] empire may suffer, from the introduction of a foreign population, whose sympathies may be decidedly anti-British, and if the majority be Americans, strongly attached to their own country and peculiar institutions.

Taking that view of the question it assumes an alarming aspect and suggests a doubt as to the policy permitting the free entrance of foreigners into the British Territory for residence, under any circumstances whatever, without in the first place requiring them to take the oath of allegiance, and otherwise to give such security, for their conduct, as the government of the country may deem it proper and necessary to require at their hands.

It is easy, in fact, to foresee the dangerous consequences that may grow out of the unrestricted immigration of foreigners into the interior of Fraser’s River. If the majority of the immigrants be American, there will always be a hankering in their minds after annexation to the United States, and with the aid of their countrymen in Oregon and California, at hand, they will never cordially submit to British rule, nor possess the loyal feelings of British subjects.13

"

Douglas thereupon posed a fundamental query to the Colonial Office in London respecting the future, which is just as appropriate for us to ask each other in the present day: how best to respond to newcomers in our midst.

"Out of the considerations thus briefly reviewed, arises the question which I beg to submit for your consideration, as to the course of policy that ought, in the present circumstances to be taken, that is whether it be advisable to restrain immigration, or to allow it to take its course.

"

Douglas closed his letter respectfully, as he was wont to do. “I shall be most happy to receive your instructions on the subjects in this letter.”14

Douglas’s May 8 letter speaks not only to the character of newcomers as Douglas perceived them, but also to his assumptions respecting the unexpected turn of events. During his years in the fur trade and then as governor of Vancouver Island, with its white population almost wholly linked to the fur trade, Douglas’s authority had been taken for granted by both current and former HBC employees.

Not so in the gold rush, as Douglas was already finding out and would continue to do so.15 Gold miners had no reason beyond immediate convenience to respect British colonial authority. Nor did Douglas have reason to respect uninvited newcomers given their wide range of backgrounds and outlooks unfamiliar to him and so almost by definition not to his liking.

Maintaining everyday control over cascading events

Even while awaiting a response from the Colonial Office to his May 8, 1858, letter, which would not reach Douglas until September 30, four and a half months later, when the mining season was winding down due to the colder weather, he almost certainly marshalled in his mind the three influences that had guided, and would continue to guide, his outlook and actions.

The first influence that would assist Douglas in maintaining control was confidence in himself and in the decisions that he made as a matter of course in the everyday, be it in the fur trade or now, unexpectedly, a gold rush. The second was the everyday comfort of his family with Amelia, which by 1858 comprised a seven-year-old son and five daughters between the ages of four and twenty-four. The third influence guiding his outlook and actions was the long-distance relationship he had forged on paper over the past half-dozen years with the distant Colonial Office.

While awaiting a response, Douglas regularly updated London respecting actions taken perforce on his own volition. Among those initiatives, he on May 8 wrote at length to the Colonial Office and issued a proclamation “asserting the rights of the Crown to all gold in its natural place of deposit,” which he had published in the newspapers of the Oregon and Washington Territories.16

Given “boats and other small craft from the American Shore were continually entering Fraser’s River, with passengers and goods, especially Spirits, Arms, Ammunition, and other prohibited and noxious Articles,” Douglas also “took immediate steps to seek to put a stop to those lawless practices by issuing a Proclamation” warning of the consequences of doing so, to be distributed by the British Royal Navy ship Satellite that had arrived at the Vancouver Island port of Esquimalt to assist in marking out an international boundary with the United States. Douglas was by now convinced that “it is utterly impossible, through any means within our power, to close the gold districts against the entrance of foreigners, as long as gold is found in abundance.”17

Douglas experiencing the gold rush first-hand

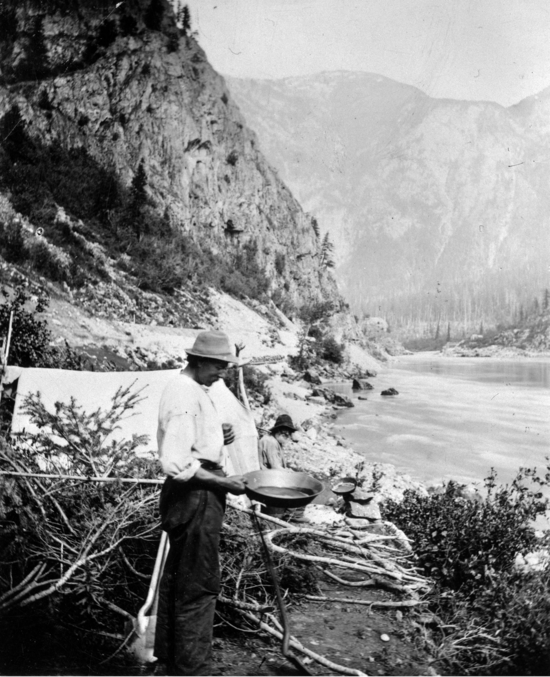

It is not surprising, given his travels in the future British Columbia over the previous three decades, while employed in the fur trade, that Douglas early on determined to experience the gold rush first-hand. In letters of June 10 and 15, 1858, to the Colonial Office, and in a letter to the Hudson’s Bay Company of June 7, he described his trip. The fifty-five-year-old Douglas boarded Satellite, “anchored off the mouth of Fraser’s River,” and headed up the river to the long-time HBC post of Fort Langley. From there he travelled four days upriver “in canoes manned chiefly by native Indians” to gold diggings extending from the small post of Fort Hope as far as it was possible to go given “the present high state of the River.” In one twenty-mile stretch Douglas counted “about 190 men, and there was probably double that number of native Indians, promiscuously engaged with the whites in the same exciting pursuit.”18

Gold’s appeal lay, Douglas came to appreciate, in the precious metal’s combination of easy accessibility, at this point being “taken entirely from the surface,” and in its assured high value. He observed “six parties of Miners, successfully engaged in digging for Gold, on as many partially uncovered River Bars” containing gold in the form of flecks, “there being no excavation on any of them deeper than two feet.” The leader of the most successful party Douglas encountered “produced for my inspection the product of his morning’s (6 hours) work, with a rocker [not unlike a child’s sand sifter on the beach] and three hands besides himself, nearly 6 ozs. of clean float gold, worth one hundred dollars in money, being at the rate of 50 dollars a day for each man employed.” Other miners with whom Douglas talked “were making from two and a half to 25 dollars to the man for the day.” Yet others “had found ‘flour gold,’ that is, gold in powder floating on the water of Fraser’s River during the freshet,” the note referring to fast-flowing water resulting from melting snow. Douglas’s references to American currency speak to these and other miners’ identities, as also does Douglas’s description of one of those with whom he spoke as “an old California miner.”19

Minding gold miners

Douglas also witnessed what would be the first of numerous disagreements between Indigenous peoples and miners, the former perceived to be trespassing on what miners considered to be their territory. He described “white Miners…in a state of great alarm on account of a serious affray which had just occurred with the native Indians, who mustered under arms, in a tumultuous manner, and threatened to make a clean sweep of miners assembled there.”20

Every disagreement has two sides, and this one Douglas resolved for the interim by taking “the leader in the affray, an Indian, highly connected in their way, and of great influence, resolution, and energy of character, into the Government service, and found him exceedingly useful in settling other Indian difficulties.” Douglas described how he “spoke with great plainness of speech to the white miners, who were nearly all foreigners, representing almost every nation of Europe,” as to how “they were permitted to remain there merely on sufferance; that no abuses would be tolerated, and that the Laws would protect the rights of the Indian, no less than those of the white man.”21

Douglas informed the miners that the land was “not open for the purpose of settlement,” although, he confided in a letter to the HBC, “the whole district of Fraser’s River should be immediately thrown open.” He was taking steps to have it surveyed so as “to lay it out in convenient allotments for sale.”22 Fundamental change was on the way.

Douglas also sought to ease the situation generally during what would be the first of numerous such visits. He wrote that he appointed “a British Subject, as Justice of the Peace for the District of ‘Hill’s Bar,’ and directed the Indians to apply to him for redress, whenever any of them suffer wrong, at the hands of white men, and also cautioned them against taking the Law into their own hands, and seeking justice according to their own barbarous customs.” Douglas appointed “Indian Magistrates, who are to bring forward when required any man of their several Tribes, who may be charged with offences against the Laws of the country, an arrangement which will prevent much evil.” Douglas feared that, except for “the exercise of unceasing vigilance on the part of the Government, Indian troubles will sooner or later occur.” He noted that the recent defeat in Oregon Territory of American troops headed by Colonel Edward Steptoe, after whom the event is known, had “greatly increased the natural audacity of” Indigenous peoples. From Douglas’s perspective, “it will require I fear the nicest tact to avoid a disastrous Indian war.”23

Attending to the mainland

His spring 1858 trip up the Fraser River had another outcome in Douglas’s fuller realization, set forth initially in his May 8 letter and followed up in a long letter of early June, that the mainland, whose non-Indigenous population prior to the gold rush was 150 or so persons and over which he had no authority, mattered greatly over the longer term:

"My own opinion is that the stream of immigration is setting so powerfully towards Fraser’s River, that it is impossible to arrest its course, and that the population will occupy the land as squatters, if they cannot obtain a title by legal means. I think it is a measure of obvious necessity, that the whole country be immediately thrown open for settlement, and that the land be surveyed and sold at a fixed rate not to exceed twenty shillings an acre…Either that plan or some other better calculated to maintain the rights of the Crown, and the authority of the Laws, should, in my opinion, be adopted with as little delay as possible, otherwise the country will be filled with lawless crowds, the public lands occupied by squatters of every description, and the authority of Government will ultimately be set at naught.24

"

On the trip’s completion, the captain of the Satellite, the Royal Navy ship which had provided Douglas with water transportation, was ambivalent respecting its outcome. He described to the Colonial Office how “Mr. Douglas the Governor of Vancouver’s Island appears to have acted with exceeding ability & judgement, so far as he is able, but he has no staff whatever to support or assist him & his position at the present time is one of immense difficulty, & anxiety.”25

What almost certainly sustained Douglas during the gold rush’s first heady months were his decades minding fur trade employees not that different in backgrounds than many of the miners, or so he thought. Just as the fur trade was hierarchical, so Douglas similarly viewed the gold rush and sought with middling success to make it so.

Enter Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton

During these same weeks and months that the gold rush was exploding, the query in James Douglas’s letter of May 8 to the Colonial Office in faraway London as to “whether it is advisable to restrain immigration, or to allow it to take its course” hung over the decisions Douglas made. His uncertainty as to how to proceed, given he had no authority beyond Vancouver Island, caused him to return to his query in a letter written to the Colonial Office on July 26, two and a half months after the original letter to which he had as yet had no reply:

"I am, not without cause, looking forward most anxiously to receiving your instructions, respecting the plan of Government for Fraser’s River. The torrent of immigration is setting in with impetuous force, and to keep pace with the extraordinary circumstances of the times; and to maintain the authority of the Laws, I have been compelled to assume an unusual amount of responsibility.26

"

Douglas’s May 8 letter would, on its arrival in London on June 25, be referred to the incoming secretary of state for the colonies. Douglas had written to Henry Labouchere, who had held that position since 1855, but now the prolific novelist, playwright, poet, and sometime Member of Parliament Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton was in charge:27 Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, as he was named in the Colonial Office and in Parliament, Sir Edward, as he was termed within the Colonial Office, and Lytton, as he was known to outsiders and is mostly used here.28 Due to his dislike of Eton’s headmaster, Lytton had rejected attendance at England’s elite boys’ boarding school. Instead he had been privately schooled before, in the usual upper-class practice, attending Cambridge University.29 Lytton’s background was a world away from the Scottish private school to which James Douglas, his contemporary in age, had been dispatched from British Guiana, but on the other hand not that different given both men came of age in the shadow of the British Empire.

Even as Douglas was worrying himself through the summer of 1858, Lytton twice responded thoughtfully and respectfully to his May 8 letter. The two letters asking for advice, both written on July 1, reached Victoria in early September. It would, in other words, take virtually the entire 1858 mining season for Douglas’s key question respecting the Colonial Office’s policy toward unrestrained immigration occasioned by the gold rush to get a response. In the interim Douglas continued to be on his own, trusting his resources, such as they were, and common sense.

The first of Lytton’s two July 1 letters referenced the new colony’s defences, being for that reason written in “Confidence.” Douglas was informed that “the Officers commanding Her Majesty’s Vessel at Vancouver’s Island will be directed to give you all the support in their power…if the Civil Government should require a force to maintain order among the adventurers resorting to the Gold Fields.” Lytton expressed his confidence in Douglas so far as possible acting peaceably:

"Her Majesty’s Government feeling the difficulties and critical nature of your present circumstances have not hesitated to place these considerable powers in your hands, but they rely upon your forbearance, judgment and conciliation to avoid all resort to Military or Naval force, which may lead to conflict and loss of life, except under the pressure of extreme necessity.

"

Lytton reminded Douglas of the differing goals of his long-term employer, the profit-based Hudson’s Bay Company, and the British government and Colonial Office. Douglas’s loyalty must now be, and must be seen to be, solely to the latter:

"Still less need I impress upon you the importance of avoiding any act which directly or indirectly might be construed into an application of imperial resources to the objects of the Hudson’s Bay Company in whose service you have so long been engaged. Even the suspicion of this, however unfounded, would be eminently prejudicial to the Establishment of civil government in the Country lying near the Fraser’s River, and would multiply existing difficulties and dangers.30

"

Thus, rather than relying on HBC employees, Douglas was to encourage “the leading men amongst the American Immigrants…to co-operate with you in preserving order amongst their countrymen.” Looking to the future, “all claims and interests must be subordinated to that policy which is to be found in the peopling and opening up of the new country with the intention of consolidating it as an integral part of the British Empire.”31

Lytton’s second letter of July 1, also responding to Douglas’s May 8 letter, approved on behalf of Her Majesty’s Government “the course which you have adopted in asserting both the dominion of the Crown over this region and the right of the Crown over the precious metals,” and expressed the wish that Douglas would “continue [his] vigilance” in doing so. Lytton responded at length to Douglas’s specific query respecting policy toward gold miners:

"It is in no part of their [Her Majesty’s Government’s] policy to exclude Americans and other foreigners from the Gold fields. On the contrary you are distinctly instructed to expose no obstacle whatever [underlining in original] to their resort thither for the purpose of digging in those fields, so long as they submit themselves, in common with the subjects of Her Majesty, to the recognition of Her Authority, and conform to such rules of Police as you may have thought proper to establish.

Under the circumstances of so large an immigration of Americans into English Territory, I need hardly impress upon you the importance of caution and delicacy in dealing with those manifest cases of international relationship and feeling which are certain to arise, and which but for the exercise of temper and discretion might easily lead to serious complications between two neighbouring and powerful States…

Her Majesty’s Government must leave much to your discretion on this most important Subject; and they rely upon your exercising whatever influence and powers you may possess in the manner which from local knowledge and experience you conceive to be best calculated to give development to the new Country and to advance Imperial interests.32

"

As the two letters attest, the adjacent United States was ever on the Colonial Office’s mind.

Lytton looking ahead in time

Lytton, for his part, even as the two letters were making their way to North America, was not playing for small change with respect to British Columbia, but for the jackpot. He was committed in principle and in practice to the Imperial project in which Britain was engaged around the world.33 Two decades earlier Lytton had, as a Member of Parliament, so declared himself to his constituents:

"England is essentially a colonizing country—long may she be so!—to colonize is to civilise. Be not led away by vague declamations on the expense and inutility of colonies. When you are told to give up your dependent possessions—consider first whether you wish this island, meagre in its population, sterile in its soil, limited in its extent, to hold a first rate empire, or to constitute a third rate nation…But would I maintain a colony by force of arms when that colony desires to be free, and can support itself? No!34

"

Implementing British Columbia’s colonization

The roadmap to British Columbia’s colonization was firmly in place by the time Lytton had, a month earlier on June 5, 1858, been named secretary of state for the colonies. Parts of North America and of the Caribbean had been colonized from the early 1600s onward, parts of Europe and Asia from the eighteenth century, and parts of sub-Saharan Africa from the early nineteenth century. More recently, the Falkland Islands were made a British colony in 1841, Hong Kong in 1843, Sarawak and North Borneo in 1846, Vancouver Island in 1849, Victoria in today’s Australia in 1851, and the Cocos Islands in the Indian Ocean in 1857. Now it was British Columbia’s turn.

So it was that Lytton, consistent with his view on Britain’s role in the world, virtually overnight transformed a still almost wholly unknown place into a second Pacific coast British colony complementing Vancouver Island. He put his plan into place almost immediately.

A “Bill to provide, until the Thirty-first Day of December (One thousand eight hundred and sixty two), for Government of New Caledonia,” as the mainland had been called during the fur trade, was introduced into the House of Commons in London on July 1, the same day Lytton wrote the two letters to Douglas. The bill was to be debated in the House on July 8, 12, and 13. Drawing on Douglas’s letters, to which he added some literary flourishes, Lytton made his case to the House of Commons at the beginning of the bill’s second reading on July 8. He began by describing how unusual the situation was, as compared to “other colonies which have gone forth from these islands” where “something is known of the character of the colonists.” Hence his goal:

"Among settlers so wild, so miscellaneous, perhaps so transitory, and in a form of society so crude…the immediate object is to establish temporary law and order amidst a motley inundation of immigrant diggers, of whose antecedents we are wholly ignorant, and of whom perhaps few, if any, have any intention to become resident colonists and British subjects…with the avowed and unmistakable intention of yielding its sway at the earliest possible period to those free institutions for which it prepares the way.

[Given] the discovery of goldfields, the belief that those goldfields will be eminently productive, the number of persons of foreign nations and unknown character already impelled to the place by that belief, I need say no more to show the imperative necessity of establishing a Government wherever the hope of gold—to be had for the digging—attracts all adventurers and excites all passions…Thus, the discovery of gold compels us to do at once, what otherwise we should very soon have done—erect into a colony a district that appears, in great part, eminently suited for civilized habitation and culture.35

"

As for governance, the legislation would empower the Crown, for a limited period, till December 1862, to make laws for the district by Orders in Council.

In making the case for immediate action “to secure this promising and noble territory from becoming the scene of turbulent disorder, and to place over the fierce passions which spring from the hunger for gold the restraints of established law,” Lytton foresaw a future “in that new world” that he could not have imagined would come to pass in a mere dozen years. In respect to the much smaller nine-year-old British colony of Vancouver Island, he proposed “to leave the question of annexation open to further experience, and the Act will empower the Crown to annex Vancouver to New Caledonia, if the Legislature of the island intimate that desire by an Address to the Crown.”

Looking eastward across the continent, Lytton astutely anticipated the next quarter century:

"I do believe that the day will come, and that many present will live to see it, when, a portion at least of the lands on the other side of the Rocky Mountains being also brought into colonization and guarded by free institutions, one direct line of railway communication will unite the Pacific to the Atlantic.”36

"

The House of Commons debate

Following Lytton’s July 8, 1858, speech in the House of Commons, his Colonial Office predecessor, Henry Labouchere, opened debate respecting the proposed British colony of New Caledonia by paying “a humble tribute to the excellent qualities of Governor Douglas” and remarking on the relative lack of conflict with Indigenous peoples as compared with the adjacent United States. Labouchere proposed that the new colony be renamed, given “a large island in the neighbourhood of Australia belonging to France bore the name already.”37

None of the speakers following Labouchere opposed the bill, but rather touched on topics linked to their own expertise and interests. In order of speaking, they foresaw how “the Indians must disappear, and the more rapidly the better.” They applauded how the bill would “create a counterpoise to the power of the United States in these regions,” over which Douglas was “most fitted” to have charge. They emphasized that the HBC monopoly must end and the boundary must be fixed so as to prevent “a repetition of previous difficulties with the United States.” They advised the new colony to avoid the Vancouver Island experience, where the high price of land “prevented colonization from being carried on to any great extent,” but rather to make land “more easily obtainable, so that out of the shifting population who might be attracted to the colony a deposit of good settlers should be left,” in consequence to “fix such a price upon the land as would stimulate population.” Coming full circle, a lone speaker dismissed Douglas as “a very incompetent man” for “the duties proposed to be entrusted to him” because “he had never been accustomed to deal with white men; all his dealings were with Indians.”38 No one disagreed with another speaker who rose to “congratulate the right hon. Baronet on this good commencement of his Colonial administration.”39

The question of the new colony’s name surfaced at least twice. In the initial debate one speaker suggested a “native name,” another “the colony of Lytton Bulwer.” The names Pacifica and New Albion, as the long-ago explorer Sir Francis Drake had termed the area, were considered without enthusiasm.40 On the bill reaching the House of Lords, “after no opposition had been offered to the principles of the Bill in the other house,” it was read for the first time on July 21 and for the second time on July 26, when “New Caledonia” was replaced by “British Columbia,” being the name proposed by Queen Victoria. The bill passed the next day. Returned to the House of Commons, the amended bill passed on July 30 and was given royal assent on August 2, 1858. Within a month the deed was done without contention or controversy.

Now not one but two British colonies shared the North American Pacific Northwest between them.

Enter the Royal Engineers

A confidential letter from Lytton dated July 16, 1858, alerted Douglas that it was “the desire of Her Majesty’s Government” to appoint him as governor of British Columbia for a six-year term “in conjunction with your present Commission as Governor of Vancouver’s Island.” The new appointment was on the condition he “entirely unconnected” himself as employee or shareholder from the HBC, whose legal rights to both Vancouver Island and the mainland would in any case shortly terminate.41

Initially all seemed to be well. One of Lytton’s two letters shared with Douglas the news of “an act passed by the Imperial Parliament authorizing the establishment of a regular Government in the Territory West of the Rocky Mountains,” which had been without a formal status since its acquisition a dozen years earlier after the 1846 boundary settlement. Queen Victoria had herself named her newest possession, whose future Lytton evoked in glowing terms:

"I need hardly observe that British Columbia, for by that name the Queen has been graciously pleased that the country should be known, stands on a very different footing from many of our early Colonial settlements. They possessed the Chief elements of success in lands which afforded safe, though no very immediate sources of prosperity. This territory combines in a remarkable degree the advantages of fertile lands, fine Timber, adjacent Harbors, rivers, together with rich mineral products. These last, which have led to the large immigration of which all accounts speak, furnish the Government with the means of raising a revenue which will at once defray the necessary expenses of an Establishment.42

"

Lytton’s July 31 letter put the onus on Douglas to determine the best way forward within the constraints emanating from the Colonial Office, which included that its newest colony become self-supporting:

"The question of how a revenue can best be raised in this new country depends so much on local circumstances upon which you possess such superior means of forming a judgment to myself, that I necessarily, but, at the same time willingly, leave the decision upon it to you, with the remark that it will be prudent on your part, and expedient to ascertain the general sense of the Immigrants upon a matter of so much importance. Before I leave this part of the subject I must state that whilst the Imperial Parliament will cheerfully lend its assistance in the early establishment of this new Colony, it will expect that the Colony shall be self supporting as soon as possible. You will Keep steadily in view that it is the desire of this Country that representative Institutions, and self Government should prevail in British Columbia when by growth of the fixed population the material for those Institutions shall be shown to exist; and that to that object you must from the commencement aim and shape all your policy.43

"

Lytton’s letter to Douglas written a day earlier, on July 30, 1858, the day the bill creating the British colony of British Columbia passed into law, introduced another element into the Colonial Office’s relationship with its newest colony that would initially be welcomed, but later become contentious from Douglas’s perspective. Lytton’s letter read in its entirety:

"I have to inform you that Her Majesty’s Government propose sending to British Columbia by the earliest possible opportunity an Officer of Royal Engineers (probably a Field officer, with two or three Subalterns) and a Company of Sappers and Miners made up to One hundred and fifty non-Commissioned Officers and men.

I must trust to you to make such arrangements in the colony for the reception of this party as you may deem necessary or suitable.

I shall provide the Officer in command with general instructions for his guidance of which you shall have a copy.44

"

Lytton’s letter of July 31 tied his vision for the new colony to the Royal Engineers, who he had a day earlier, without forewarning, informed Douglas were on the way. At the end of enumerating their tasks, the letter slid into the hard reality that the new colony would in due course be paying for their services.

"It will devolve upon them to survey those parts of the Country which may be considered most suitable for settlement, to mark out allotments of land for public purposes, to suggest a site for the seat of Government, to point out where Roads should be made, and to render you such assistance as may be in their power on the distinct understanding however, that this force is to be maintained at the Imperial cost for only a limited period; and that if required afterwards, the Colony will have to defray the expense thereof.45

"

Lytton’s July 31 letter respecting the Royal Engineers comes across as duplicitous, given it would either soon be, or already had been, decided within the Colonial Office that virtually the whole cost of the Royal Engineers would be downloaded onto British Columbia. Writing two weeks later, the permanent under-secretary for the colonies, Herman Merivale, recounted that decision to the secretary of state for war:

"It will be necessary that an account should be kept of all the expenses incurred for this expedition, it being intended that the new Colony shall ultimately defray the entire cost of its establishment. In the meanwhile arrangements are being made with the Lord Commissioners of the Treasury to advance funds, on the requisition of the Governor, sufficient to cover the expense which this Party of Engineers shall occasion in case there should be no Colonial resources immediately available for that purpose.46

"

Merivale had, to his credit, sought to get part of the cost “paid from Army Funds,” only to have the proposal rejected by the War Office given that the “men are required for Colonial and Surveying purposes.”47

The difference in opinion between the Colonial Office and the War Office respecting costs would be decided at the highest level. Writing on October 18, 1858, respecting the “difference, which has arisen between the War Office and yourself,” Benjamin Disraeli, then Chancellor of the Exchequer and a future prime minister, informed Lytton that “it was understood that the regimental pay of the detachment of Royal Engineers, sent to British Columbia, should be paid by the War Office, and that the working, or extra, [all underlining in original] pay, although advanced from imperial funds, should be repaid by the Colony,” which “is in accordance with previous practice.”48

What British Columbia gained by this decision was a small part, but at least a part, of the Royal Engineers’ cost.

Lytton’s expectations for Douglas

Embedded in Lytton’s letters to Douglas of July 30 and 31, 1858, welcoming him to the inner workings of the Colonial Office were five expectations and obligations respecting his oversight of British Columbia’s new status as a British colony. In summary:

- Cut HBC ties. The first obligation, if personally troubling given Douglas’s long career in the fur trade, was doable. Lytton’s second letter of July 31, which was confidential, reiterated the necessity for him, should he accept the appointment, to relinquish his ties with the Hudson’s Bay Company and related entities.49

Deal respectfully with Indigenous peoples. A second obligation, also not unexpected, was for Douglas to pursue a benign policy toward Indigenous peoples:

"

I have to enjoin upon you to consider the best and most humane means of dealing with the Native Indians. The feelings of this country would be strongly opposed to the adoption of any arbitrary or oppressive measures towards them…This question is of so local a character that it must be solved by your Knowledge and experience, and I commit it to you in the full persuasion that you will pay every regard to the interests of the Native which an enlightened humanity can suggest. Let me not omit to observe that it should be an invariable condition in all bargains or treaties with the Natives for the cession of Lands possessed by them, that subsistence should be supplied to them in some other shape, and above all that it is the earnest desire of Her Majesty’s Government that your early attention should be given to the best means of diffusing the blessings of the Christian Religion and of civilization among the Natives.50

"- Conciliate newcomers. A third obligation put on Douglas was to “appease the mixed population which will be collected in British Columbia,” to seek “by all legitimate means to secure the confidence and good will of the Immigrants,” and in doing so to “exhibit no jealousy whatever of Americans or other foreigners who may enter the country.”51 It seems Lytton could already foresee the eventual makeup of the non-Indigenous population of the new colony.

and 5. Be self-supporting while also funding the Royal Engineers. The fourth and fifth obligations would be in combination the most difficult, indeed impossible, for Douglas to realize. As put by Lytton in his July 31 letter respecting the fourth obligation, “I must state that whilst the Imperial Parliament will cheerfully lend its assistance in the early establishment of this new Colony, it will expect that the Colony shall be self supporting as soon as possible.”52

Running counter to Lytton’s fourth obligation was his hardening position respecting the funding of the Royal Engineers. The fifth obligation, as set out on July 31, stated “that this force is to be maintained at the Imperial cost for only a limited period; and that if required afterwards, the Colony will have to defray the expenses thereof.”53

Within the month, even before the Royal Engineers left England on what would be a four-month voyage to British Columbia, Lytton informed Douglas, in line with an earlier letter from the permanent under-secretary of state for the colonies to the War Office, that “any expenditure which the British Treasury shall have incurred on this account will have to be reimbursed by the Colony, as soon as its circumstances permit.”54 British Columbia was thereby commanded to fund not only itself, but also the cost of a quasi-military contingent over which Douglas had had no say as to whether it was wanted or needed.

From Douglas’s May 8 query to the instructions he received for a colony in the making was the longest of distances and tallest of orders. Should Douglas accept the invitation, the weight of newly proclaimed British Columbia was on his shoulders, alongside his continuing governorship of Vancouver Island.

Douglas updating the Colonial Office

In the interim, unaware of what was happening in London, Douglas kept updating the Colonial Office respecting gold miners, even though they were not on his turf, living as he did in Victoria on Vancouver Island. On July 1, 1858, Douglas reported how, based on numbers of arriving passengers, “this country and Fraser’s River have gained an increase of 10,000 inhabitants within the last six weeks…who have been quiet and submissive to the Laws of the country.” From what he had been told, much as with his earlier report, “about two thirds of the emigrants from California are supposed to be English and French, the other one third are Germans and native citizens from the United States.”55 A minute added on the letter by Herman Merivale gave a nearly audible sigh of relief: “This conveys the very important information that only a very small proportion of the immigrants are Americans—only part of a third.”56 Recognition of the danger of American intervention extended to the Colonial Office in faraway London.

Four letters later, Douglas reported on August 19, 1858, there were “about 10,000 foreign miners, in Fraser’s River,” with upward of three thousand of them “profitably engaged in gold mining.” Among the others, Douglas applauded five hundred gold miners “composed of many nations, British subjects, Americans, French, Germans, Danes, Africans and Chinese who volunteered their services immediately on our wish to open a practicable route into the interior of the Fraser’s River District.” Not only did the men volunteer to build a road, but each of them “on being enrolled into the corps, paid into our hands, the sum of 25 dollars, as security for good conduct.” As to their conditions,

"They receive no remuneration in the form of pay, the Government having merely to supply them with food while employed on the road, and to transport them free of expense, to the commencement of the road on Harrison’s Lake [on a tributary of the Fraser River]; where the money deposit of 25 dollars is to be repaid to them in provisions, at Victoria prices, when the road is finished.57

"

The construction of roads across the vast place that is today’s British Columbia would be a continuing priority for Douglas.

Douglas’s next letter, dated August 27, related the killing of two miners “by Indigenous peoples of Fraser’s River,” a total initially reported erroneously as “42 gold miners.” Douglas described the acquisition from the Satellite and from another vessel of “a force of 33 officers and men to proceed with me to the scene of the disaster.” Douglas’s goals in so acting, he explained to the Colonial Office, were twofold: “the enforcement of such laws as may be found necessary for the maintenance of peace and good order among the motley population of foreigners, now assembled in Frasers River, and also practically to assert the rights of the Crown, by introducing the levying of a Licence duty on persons digging for gold, in order to raise a revenue for the defence and protection of the Country.”58 As would continue to be his practice, Douglas from time to time took aim at persons not as suitably British as he preferred them to be.

The new order of things

In the new order of things in London, which was yet unknown to Douglas, British Columbia was officially proclaimed a British colony on August 2, 1858. Doing so caused Lytton as secretary of state for the colonies to attend more closely to this distant corner of the vast British Empire than the Colonial Office might otherwise have done, given the recent proliferation of colonies around the world.

The months between letters being dispatched from the Colonial Office and responses received from Douglas, which only began to be remedied at year’s end by a more expeditious mail route, made the precision of this sole means of communication essential.59 That arriving letters were passed between Colonial Office officials for individual comments in the form of minutes contributed to more nuanced responses than would otherwise have been the case.

Douglas’s August 19 letter describing miners volunteering for road construction was, like the others, repeatedly minuted on its arrival in London on October 11. In the perspective of one official, “this is an interesting dispatch—and speaks well for Governor Douglas’s management of his miscellaneous population.”60 Another minute referenced Colonial Office policy generally:

"Write in reply…that Sir E. Lytton has seen with very great satisfaction the ability, the resource, and tact & conciliation wh Govr Douglas has displayed under circumstances so difficult & unexpected as to task the highest powers of administration…I think that as yet we have abstained from praising and that now we ought in justice to Govr Douglas to give him credit for great capacity under trying circumstances. Approval especially when discriminately given is not only just in his case but is good policy.61

"

Upping the demands on British Columbia

What had initially especially resonated for Lytton respecting incoming letters was his conviction based on what Douglas wrote that “the affairs of Government might be carried on smoothly with even a single company of infantry,” and “under proper management, that the country will produce a large revenue for the Crown.” Indicative of how rapidly Lytton’s perspective had shifted, it was now British Columbia’s profitability for the mother country as opposed to its well-being that, even in the infant colony’s first months of existence, took priority. Colonies were intended to benefit the mother country.

The key to British Columbia’s future as Lytton envisaged it lay, not unexpectedly given he had sent them, in “the superior intelligence & discipline of the Sappers & Miners, & their capacity at…expediting the work of civilization.”62 As to their funding, Lytton had already reminded Douglas in a letter dispatched on September 2, 1858, not yet received, that it now lay wholly with the new colony to provide it:

"Her Majesty’s Government expect that British Columbia shall be self supporting, and that the first charge upon the Land Sales must be that of defraying all the expenses which this Engineer party shall occasion. Any expenditure which the British Treasury shall have incurred on his account will have to be reimbursed by the Colony, as soon as its circumstances permit, and for which I have now to instruct you to make suitable provision.63

"

Lytton’s minute on Douglas’s August 19 letter instructed Colonial Office staff as to how the new colony should be viewed in light of Douglas’s description of miners volunteering for roadbuilding:

"The laudable cooperation in the construction of the road which his energy has found in the good sense & public spirit of the Miners…bears out the principle of policy on which I desired to construct a Colony that was intended to perpetuate the great qualities of the Anglo-Saxon race.

"

Perceiving British Columbia much as Douglas did, and never one to pass over an opportunity for a literary flourish, Lytton minuted on the letter how “from England we send skill & discipline—the raw material (that is the mere men) a Colony intended for free institutions & on the borders of so powerful a Neighbour as the United States of America, should learn, betimes, of itself to supply.”64

The draft of Lytton’s letter to Douglas was vetted by Colonial Office staff, causing the final version to have a sentence added respecting the Indigenous factor. This was almost certainly in response to the arrival of Douglas’s August 27 letter describing Indigenous people’s killing of two miners.65

It is small wonder Lytton confided to an acquaintance at precisely this point in time, “I feel as if the Colonial Empire would go smash if I were out of reach of the mails and messengers two days together.”66

Lytton and Douglas jointly in charge of the gold rush

Douglas and Lytton’s correspondence during the latter’s tenure as secretary of state for the colonies from June 5, 1858, to June 11, 1859, would sometimes push the boundaries, as when the Royal Engineers were dispatched solely at Lytton’s behest. Both strong-willed men, they each believed that they had charge of the gold rush, while in practice they held it jointly.

On September 9, 1858, Douglas wrote from “Fort Hope, Fraser’s River.” Having just received Lytton’s letter of July 1, answering his much earlier query respecting policy toward gold miners, Douglas expressed his “indescribable satisfaction that Her Majesty’s Government approve of the measures which I conceived it necessary to resort to, in order to assert the dominion of the Crown over the gold Districts of Fraser’s River, and the rights of the Crown over the precious metals.” In his letter, Douglas reviewed the policy he had effected so as to display strength even while persuading some miners to stay longer and possibly settle down:

"I have to observe for the information of Her Majesty’s Government that all foreigners and especially American citizens who have visited Fraser’s River since the commencement of the gold excitement, have been treated with kindness, and protected by the laws. The rights of the Crown as well as the trading rights secured by statute to the Hudson’s Bay Company, have been broadly asserted in my several proclamations, with the object of maintaining British supremacy, by establishing a moral control over the masses of foreigners, who, under the false impression that the country was free and open to all nations, and that we had no military force at our disposal, were rushing defiantly, and without ceremony into Her Majesty’s Possessions, and we succeeded by that means, in securing respect and obedience to the Laws, at a time when a policy of concession would have been mistaken for weakness and have proved injurious to British interests.67

"

Responding on December 30 to Douglas’s September 9 letter, Lytton was pleased and even more so, it would seem, relieved. “I can but repeat (and I do so with great pleasure) the testimony which I have already borne to your energy and promptitude amidst circumstances so extraordinary as those in which you found yourself placed.” The letter concluded with “cordial approval of the manner in which you appear to have carried out the two objects which at the onset of such a Colony should be steadfastly borne in view—vizt a liberal and kindly welcome to all honest immigrants, and the unquestionable supremacy of British Sovereignty and Law.”68

Douglas’s reply of September 29 to Lytton’s confidential letter of July 1 acknowledged his awareness that he should not be seen to favour the HBC. In respect to conciliating “the American population,” Douglas observed confidently their “general feeling is in favor of English rule in Fraser’s River, the people having a degree of confidence in the sterling uprightness and integrity of Englishmen, which they do not entertain for their own countrymen.”69 A Colonial Office official was so taken by “Govr Douglas’ remark upon the general preference for English over American rule,” he recommended it be forwarded to the Admiralty.70

To a confidential letter of July 16 alerting Douglas to the mainland’s governance and to his being invited to take charge of British Columbia for “six years at least,” being 1864 or longer, Douglas responded to Lytton on its October arrival with the expected appreciation, as he also did to his trio of letters written at the end of July notifying Douglas of the legislation’s passage and instructing him accordingly.71

Douglas reporting on gold miners

Douglas for his part continued to give priority to the task at hand. To monitor the situation on the ground, he travelled in early October 1858 to the gold fields accompanied by “a force of Thirty-five non-commissioned officers and men” furnished by the Royal Navy ship Satellite, which had also supported his earlier travels. Finding “the Indian population” at Fort Hope “much incensed against the miners; [Douglas] heard all their complaints, and was irresistibly led to the conclusion that the improper use of spirituous liquors had caused much of the evils they complained of,” and so declared “the sale or gift of spirituous liquors to Indians, a penal offence,” which it would remain.72

In reporting on his travels, Douglas repeatedly sought to engage the Colonial Office in the everyday of the gold rush. Fort Hope’s now three hundred-strong “white population” was, he reported from there, “engaged in trade, and other pursuits,” living in tents and huts, and “all desirous of settling in the country.” While there, Douglas appointed a justice of the peace and chief constable. He then headed to Fort Yale, whose population he estimated as two thousand, and similarly appointed officials. In the fifteen-mile distance, he and the others counted three thousand gold miners along the Fraser River’s banks, with some of whom Douglas stopped and talked. “I was much struck with the healthy robust appearance of the miners…all seemingly in good health, pleased with the country, and abundantly supplied with wholesome food.” From Douglas’s perspective, “the whole course of the river exhibited a wonderful scene of enterprise and industry.”73 In his minute on Douglas’s letter, Lytton complimented “the ability and power of organization wh he possesses.”74

Writing two weeks later, on October 29, Douglas was more realistic, by virtue of his recent trip, about the obligations incurred by his having accepted the governorship.

"The class of men who are mining in Fraser’s River are composed of all nations, some of them no doubt respectable, but when I landed at Fort Yale in my late journey to Fraser’s River, it struck me that I had never before seen a crowd of more ruffianly looking men, than were assembled on that occasion.

About 3000 were present, and to add to the horror of the scene, many of them were drunk; things, however, wore a better appearance next day, and after saying a few kind words to them, they were profuse in acclamations, and did, at my command, give three cheers for the Queen, but evidently with a bad grace. There is a strong American feeling among them, and they will require constant watching, until the English element preponderates in the Country.75

"

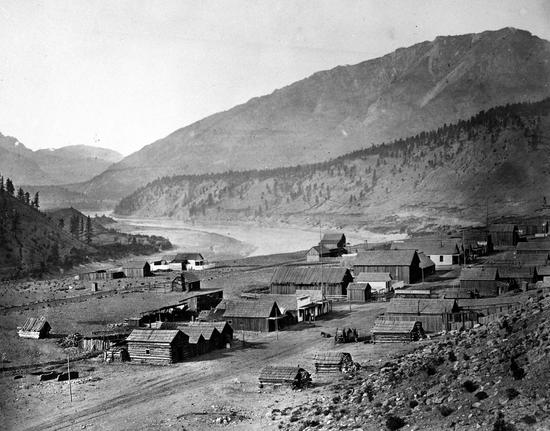

Douglas nonetheless enthused how “the Town site of ‘Lytton’ was laid out, and now contains 50 houses and a population of 900 persons,” with a land route to the site, which had been strategically named in Lytton’s honour, completed at a cost of £10,000. “The Revenue collected already in the country is to defray the whole expense” of the road, by which provisions and other supplies were now able to be brought by mule train to Lytton, similar to how mules were also being used elsewhere across the mainland to transport goods.76 Port Douglas, named for Douglas, was now served by river steamers. Douglas estimated “the mining population along Fraser’s River” as 10,600.77

Writing a month later, at the end of November, Douglas noted how “a great number of miners have left Fraser’s River and returned to California and Oregon.”78 Among the departures of “100 persons a week,” some reported “having families to visit and business to settle in California, others dreading the supposed severity of the climate, others alleging the scarcity, and high price of provisions, none of them assigning as a reason for their departure the want of gold.”79 So British Columbia’s first gold-mining season drew to a close.

In the matter of finances

The two men in charge of British Columbia’s first gold rush season, one on the ground, the other in faraway London, sometimes but not necessarily had the same goals with respect to the critical issue of funding the new colony. As indicated by the tone and content of their ongoing correspondence, James Douglas was not always his own person to act as he would, whereas Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton’s flattering and cajoling did not necessarily get him his way.

One unresolvable tension, from Douglas’s perspective, given his dual role as governor also of Vancouver Island, had to do with displaced Hudson’s Bay Company employees, about whom “a sense of justice leads me to exert the little influence I possess, in protecting from injustice, men who have served their country so faithfully and so well.”80 A minute on the resultant letter reminded others in the Colonial Office respecting the HBC how “the establishment of the new Colony wd have been very different from what it was and is had we not had the service and support of the organization wh they had previously created.”81 Lytton assured Douglas that, although “no regulations giving the slightest preference to the Hudson’s Bay Company will be in future admissible,” in respect to “the Indian trade,…the Company’s private property will be protected in common with that of all Her Majesty’s subjects,” which it was.82

The far more important and immediate topic was financing the new colony. It was in this respect that Douglas and Lytton drew apart. Douglas approved in principle of Lytton’s various proposals for raising revenue “to meet the unavoidable increasing expenditure of Government,” including “opening the country to permanent settlement.” Even as Douglas agreed, though, he raised and would repeatedly do so over the half dozen years of his governorship the need for financial assistance to get the new colony up and running.

Managerial assistance for British Columbia

The October 1858 trip to the gold fields heightened Douglas’s awareness of the need for managerial, along with financial, assistance to meet his obligations. He could not do it all, as he had been wont to do of necessity in respect to British Columbia, which unlike Vancouver Island did not have capable one-time fur trade officers and others at hand:

"I am at present in great perplexity for want of efficient help…to perform the duties that now devolve upon me alone, a misfortune for myself and the Country, as both suffer in consequence of that want…

Let me therefore have the assistance of Officers, capable of managing the subordinate departments, of drafting dispatches and so forth, so as to leave me time for the executive functions of Government which are more than enough to occupy my attention.83

"

While Douglas was not yet so aware, help was on the way. In a letter written on August 14, 1858, Lytton enthused how British Columbia’s “immense resources…will at once free the Mother Country from those expenses which are adverse to the policy of all healthful colonization.” To assist, Lytton committed in respect to this “Country hitherto so wild” to have “sent from home” to fill key positions qualified men “freed from every suspicion of local partialities, prejudices and interests.”84

Matthew Begbie, appointed chief justice of the mainland colony, was already en route and Douglas’s letter spurred more action.85 As minuted on Douglas’s September 29 letter: “The Govr asks that an Attorney General, Colonial Secretary & Treasurer may be appointed.”86 What Douglas sought, Lytton was prepared to grant, including a private secretary.87 As well, the new colony needed its capital to have a name, and the original choice of Queensborough having been rejected as “not only prosaic—it is the quintessence of vulgarity,” the name chosen was “New Westminster.”88

The need for roads

In thanking Lytton for sending personnel, Douglas raised the stakes respecting the mainland colony. In his response he emphasized the need for roads, and he would continue to do so. He noted that his hopes for sustaining the economy over the long term hinged on roadbuilding. Given “Fraser’s River is the only great artery of the Country,” Douglas explained to Lytton in October 1858, he looked to a system of roads “providing access to the remote settlements of British Columbia.” That the colony was almost four times the size of Britain meant, in and of itself, that Douglas faced a daunting task:

"The Government will have to grapple vigorously with the arduous and expensive operation of opening a great system of roads, and providing access to the remote settlements of British Columbia, before its mineral resources can be developed, and become a fruitful source of revenue…

To accomplish that great object of opening up a very inaccessible Country for settlement, by the formation of roads and bridges, immediately and pressingly wanted…in a wilderness of forest and mountains, is a Herculean task, even with all the appliances of wealth and skill, and it must necessarily involve in the first place, a large expenditure, much beyond the means of the Country to defray…My own opinion of the matter is that Parliament should at once grant the sum of £200,000, either as a free gift, or a loan to be repaid hereafter, in order to give the new Colony a fair start, in a manner becoming the great nation, of whose empire it forms a part.89

"

The minutes on Douglas’s letter dissected his request at length. The under-secretary of state for the colonies, the Earl of Carnarvon, considered the letter with its request for funding no surprise:

"It is very satisfactory in many respects as showing the energy and capacity with wh Govr Douglas is creating a completely new system in the Colony and he deserves I think for it the highest praise…

This is evidence of the probable cost of the Colony wh we may expect. I have always believed that the charge next year will not fall much short of £100,000. The amount of pecuniary assistance to be given next Session to the Colony is a serious question. Where everything from the jail to the Govr’s house has to be created and wages exceed 13 shillings a day the expenses must & will be very heavy.90

"

Lytton’s minute, written the same day, got to the heart of the matter from the government’s perspective:

"It will be necessary to give the most anxious consideration to the question raised of expenditure by the Mother Country. What proposition will Parlt least unwillingly receive. Parlt which is prepared, as the Public is, to suppose the Coly at once self-supporting…The idea of a gift to any amount seems to me impossible. What occurs to me as best is a loan…rather than a guarantee, to be repaid by the Colony from Crown Lands & other revenues.91

"

Following up on Lytton’s minute, the permanent under-secretary for the colonies, Herman Merivale, astutely put the matter in a larger context:

"I have thought that, with so able a man there, it is better simply to tell him that he must pinch than to indicate where [both underlining in original] he is to pinch.

But I own I see very little prospect from his financial returns of his being at all able to meet his expenses. The winter has arrived, when receipts will be next to nothing, and, a host of pioneers & employés thrown on his hands.

As to the general question, to which Sir E. Lytton adverts, about self supporting colonies, I am afraid it is one of the many on which facts broadly contradict popular opinion.

No successful colony, founded by Englishmen in modern times, has been self supporting; or with one exception only. Upper Canada, Nova Scotia, N.S. Wales, South Australia, New Zealand, all cost this country very large sums at the outset in one form or the other, & all those with, and upon, a large English expenditure. The smaller colonies of Nth America had no such aid, or little; and their progress was very slow.

The only exception is Victoria [in Australia, originating in gold discoveries], and this scarcely a complete one; for the original “Port Phillip” was an offshoot of the very costly colony of New South Wales.

In truth we are driven back for instances to the old Nth Am[erican] Colonies, now States. They cost this country nothing; but their progress was very slow indeed, according to our impatient ideas.92

"

From early on, Douglas governed on a financial tightrope and would continue to do so.

The Royal Engineers’ cost coming into view

The other ongoing tension complicating matters further was Lytton’s demand that British Columbia be not only self-supporting but also fund the Royal Engineers. Writing at length on December 14, 1858, as the year that changed everything was coming to a close, Douglas was cautiously optimistic respecting what was and was not feasible, even as he foresaw the very large cost of the Royal Engineers:

"The American Steamer “Pacific” left this place on the 4th of Instant with 400 passengers principally returning miners, for the Port of San Francisco. The export of Gold dust by that vessel was reported to be ten thousand ounces, exclusive of a large amount in private hands. An export duty on gold would now yield a respectable amount of revenue, and together with the duties levied on imports, would probably yield an income of £100,000 per annum.

With some assistance from Parliament in the outset, either by way of loan or as a free grant, the Colony will soon emerge from its early difficulties, and defray all its own expenses. This has hitherto been accomplished without assistance from any quarter, as I have not yet drawn upon you for any expenditure incurred in the Colony; which have all, nevertheless, been paid.

I cannot however undertake immediately to defray the cost of the detachment of Royal Engineers appointed for the protection of the country; as a large sum must, this year, be provided for the erection of the many public buildings so much needed, in British Columbia. I propose building a small Church and Parsonage, a Court house, and Goal [jail] immediately at Langley and to defray the expense out of the proceeds arising from the sale of Town Lands there.93

"

The minutes on Douglas’s December letter were generally complimentary. “Edward Lytton will doubtless regard this dispatch as very satisfactory: especially as Govr Douglas is not a man to express exaggerated opinions.”94

Ongoing unease with the United States

Something else was also happening: Americans were shadowing the course of events. Douglas was very aware from the outset of the large proportion of miners who were American, which caused him to be more attentive than he might otherwise have been. It was likely common knowledge among interested Americans that, as Douglas reported to the Colonial Office at the end of November 1858, out of a hundred thousand plus ounces of gold dust produced that year, well over half had been exported to the United States.95

Douglas was also aware from early on that Americans were not unwilling to take advantage of events, and he had constantly to be on guard. When a physician at Port Townsend, just across the international boundary, complained to the Colonial Office, in a letter forwarded to Douglas, that incoming miners bringing their own tools were nonetheless compelled to purchase them from the HBC in Victoria, Douglas responded that the HBC at that point in time had no mining tools for sale and generally that,

"from the first period of the gold discoveries in Fraser’s River much petty jealously has been exhibited by the inhabitants of Port Townsend…which thought proper to feel aggrieved at the prosperity of Victoria, and commenced a crusade against British interests in general, and against the Hudson’s Bay Company in particular, and the American press in that quarter, has teemed with Articles of the most absurdly fabulous character.96

"

The ongoing border dispute over the San Juan Islands located between Vancouver Island and American territory was also on Douglas’s mind, as he had been requested by Lytton in August 1858 to monitor the situation.97

Funding the Royal Engineers

From Lytton’s perspective, which mattered the most, it was the Royal Engineers that were the answer, the magic bullet if you will. Writing in October 1858, Lytton ramped up his enthusiasm for them. There was seemingly nothing they could not accomplish, he informed Douglas, “as pioneers in the work of civilization, in opening up the resources of the Country by the construction of Roads and Bridges, in laying the foundations of a future City or Sea Port, and in carrying out the numerous Engineering Works, which in the earlier Stages of Colonization are so essential to the progress and welfare of a Community.”98

Along with the arrival in April 1859 of the main body of 121 Royal Engineers, accompanied by thirty-one wives and thirty-four children, came an ever wider gulf as to their funding.99 Even as the detachment was on its way to British Columbia, the War Office in London informed the Colonial Office that, given these “officers and men are required for Colonial and Surveying purposes,” it was up to Lytton to “make arrangements with the Treasury for the payment of the whole of the expenses involved.”100

To protect his own bottom line, Lytton had already, almost as a matter of course and without consultation, downloaded the Royal Engineers’ costs to British Columbia. His doing so even before their arrival ran counter to the practical reality of an infant colony just four months of age that was, in Douglas’s words to Lytton in his letter of November 4, 1858, not “entertaining much hope of being immediately able to meet the expense of the military establishments of the country.” Douglas pointed to “other indispensable outlay, which must be incurred before the country can possibly become a fruitful source of revenue; like a nurseling it must for a time be fed and clothed, yet I trust it will before many years re-imburse the outlay and re-pay the kind care of the mother country, with interest.”101 In a follow-up letter written the same day, Douglas was even blunter as to how “the revenues of the country will not be immediately capable of defraying the expenses of this detachment and I shall be under the necessity of drawing upon the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury…until the new Colony is in a position to meet that expenditure.”102

Douglas had by now come to realize that if he did not stick up for the mainland colony, nobody else was going to do it for him. Colonial Office minutes on his letters make clear Douglas’s November 4 response was no surprise. “This is the answer wh might be expected,” Carnarvon wrote.103 The long-experienced Arthur Blackwood made explicit the logic, or lack of it, behind the Colonial Office’s thinking:

"We have relied or pretended to rely upon the gold being produced in such quantities as would be sufficient to render B. Columbia self supporting in all respects save the salary of the Governor…In this hope we have indulged ourselves that the Colony would also have the means of defraying the expense of the detachment of Royal Engineers, and therefore, the Governor having himself given us such cheering accounts of the prospects of the place, we have never distinctly authorized him to draw upon the British Treasury for Engineers or for any other service…[His now doing so] is really no more nor less than we have expected.104

"

Douglas had been, to borrow a cliché, led down a verbal garden path with no other recourse than to put the new colony in debt for a service he had not requested in the form imposed on him.

Concluding the year that changed everything

On November 27, 1858, Douglas reaped the rewards, such as they were, of the year that changed everything, proclaiming at the long-time HBC post of Fort Langley “the Act of Parliament providing for the Government of British Columbia.” Incoming Chief Justice of British Columbia, Matthew Begbie, arrived just in time, via San Francisco, to take part in the ceremony.105

Come year’s end, Douglas thanked Lytton for “the effective steps you have taken to support my authority and the various measures which you have adopted to aid me in the arduous task of organizing the government of the Colony.”106 As for the management of the gold rush:

"I was sensible from the outset, of the arduous nature of the task of framing regulations so perfectly adapted for a comparatively unknown country, as to be unobjectionable, especially for a country situated as is British Columbia, in the close vicinity of a powerful state whose inhabitants would for a time at least form the great bulk of the population. It was to establish a legal control over the adventurers who were rushing, from all sides, into the country, to anticipate their own attempts at legislation and to accustom them to the restraints of lawful authority, that I prepared and issued the gold regulations.107

"

Carnarvon astutely minuted: “This desp.[despatch] shows how easy it is to theorise in England & how difficult it is sometimes to give effect to those theories in a new Colony.”108

Douglas’s and Lytton’s messages exchanged at year’s end point out how transformative 1858 had been. Even as they each pushed their favourites, the two men were cordial.

Douglas not unexpectedly put his emphasis on Vancouver Island, where he lived and of which he was also governor. Indicative of his ongoing preference for it, Douglas had earlier let slip respecting the location of “a sea-port Town for the Colony of British Columbia” that “should Vancouver’s Island be incorporated with British Columbia,…the safe and accessible harbour of Esquimalt Vancouver’s Island should be made the Port of Entry to sea going vessels for both Colonies.”109 Douglas also used his year-end message to point out how Victoria in particular had benefited from the newer colony of British Columbia:

"There has been a remarkable increase this year in the population of this Colony, in consequence of the discovery of Gold in Fraser’s River. Victoria from a village has grown up into a town of considerable extent, and become the seat of a large and growing trade, being still the only Port of Entry for ships bound to British Columbia.110

"